Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 95

October 14, 2016

Bob Dylan: Don’t Think Twice, He’s All Right

I awoke to the news that the Nobel Prize for Literature had been won by . . . Bob Dylan. I knew Dylan had been nominated before, but always figured this was in the realm of fantasy, like Wonder Woman being named Miss Universe. Of course we live in a land where Sonny Bono was elected to Congress and Arnold Schwarzenegger served as governor of California. (And I won’t go into current U.S. presidential politics.) So I knew that glamour figures from the entertainment field could come out on top within America’s borders. But Dylan’s elevation to the world’s top literary prize was not determined by any American citizens. The Swedish Nobel committee had their pick of current U.S. literary lights, like (for example) Philip Roth. There had not been a U.S. Nobel laureate since Toni Morrison in 1993. Such important recent writers as John Updike and Edward Albee went to their graves unrecognized.

And, of course, there are great international figures who deserve Nobels: how about a prize for playwright Tom Stoppard? But Dylan’s achievement—the first ever given to a songwriter—says something surprising about the world’s respect for American popular culture. How do I feel about this honor? Actually, I’m not quite sure. As a lover of precise word choices, I’ve never been entirely convinced by Dylan’s use of the English language. Sometimes all those phantasmagoric images in songs like “Desolation Row” seem picturesque rather than meaningful. And you’re not going to get me to coo over lyrics like, “Everybody must get stoned.” But the Nobel folks have cited Dylan "for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition," and I love this recognition for our country’s musical heritage, one that has indeed circled the globe.

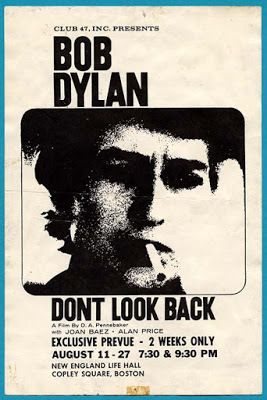

Early on, some filmmakers thought Dylan had the makings of an actor. He actually had a featured role in Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973), but it was cut drastically when his acting chops didn’t measure up to his personal charisma. So it’s doubtless a good thing Warren Beatty didn’t follow through on his impulse to cast Dylan as the male lead in Bonnie and Clyde. There was, though, a vivid 1967 D.A. Pennebaker documentary covering Dylan’s debut concert tour of England. The title is Dont Look Back, and even the missing apostrophe hints that the film’s central figure is a rebel, pushing hard against the rules of polite society.

In the film, a surly Dylan makes plain his refusal to be sucked into the starmaker machinery on which the recording industry is based. Whether meeting other musicians backstage or jousting with the press, he seems guarded and occasionally hostile. Determined not to be categorized, Dylan parries every label that journalists try to pin on him. No, he’s not a folksinger. No, he’s not an angry young man.

What many mainstream reviewers of the film missed (aside from the quality of Dylan’s musical output) is key to what attracted the young fans of the Sixties: the fact that Dylan, both offstage and on, so completely negated what their parents would consider appropriate entertainment. His slapdash mode of dress, his laconic on-stage manner, even his droning and nasal voice were affronts to the middle-aged. And Dont Look Back revealed that the defiant stance contained within Dylan’s lyrics was also a part of his behind-the-scenes persona. He was the quintessential rebel, the surly punk who had no use for his elders, the direct descendant of Brando’s Wild One and James Dean’s Jim Stark.

But he’s lasted, and evolved. And is now a Nobel Laureate. Who’da thunk?

David Remmick of the New Yorker offers his own tribute to Dylan.

Published on October 14, 2016 11:31

October 11, 2016

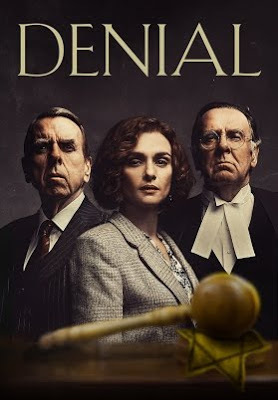

“There Oughta Be a Law”: The Legal System on Trial in “Denial”

I just saw the brilliant Ivo van Hove production of Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge. Several of the play’s longshoreman characters can’t grasp why the American judiciary system doesn’t hold sway over problems that are, frankly, psychological and moral rather than legalistic. A different view of the law shows up in Denial, the recent film about the 1996 libel trial in which British Holocaust denier David Irving accused American historian Deborah Lipstadt of defaming him in her 1993 book, Denying the Holocaust.

Irving sued Lipstadt and her publishers in Britain rather than the U.S. because within the British legal system the burden of proof is on the defendant, not the accuser. So it was crucial that Lipstadt prove beyond a shadow of a doubt that Irving (a self-made historian with a large following) was in fact an anti-Semite and a Nazi apologist, one who bent the existing facts of the Holocaust to suit his own purposes. As was said at the time in newspapers around the globe, history itself was on trial.

This sounds like the making of a highly dramatic film. We all love courtroom dramas, with their rising tension, surprise witnesses, and stunning reversals. Denial, has a problem, though. The film tries hard to be true to what actually happened in that London courtroom. (Given the nature of its central issue, sticking to facts was clearly essential.) And so some of the things we adore about courtroom movies just weren’t allowed to happen here. I’m sure screenwriter David Hare (himself an eminent dramatist) really struggled to inject theatrical twists and turns into a story for which the outcome is well-known and scripted courtroom fireworks were not allowed.

I went to see Denial both because its subject matter interested me and because I, once upon a time, served on the same faculty as Deborah Lipstadt. This was early in her academic career (and mine), well before she made her mark as a respected professor of modern Jewish history and Holocaust studies at Atlanta’s Emory University. I remember her back then as smart, feisty, and focused. A sturdy-looking natural redhead, she was definitely not a push-over. I know for certain that she didn’t suffer fools gladly.

Movies being movies, Rachel Weisz is a great deal prettier than the woman she portrays on screen. The auburn hair Weisz sports in the film is stylish in a way that Lipstadt’s wash-and-wear do is not. But the British-born Weisz does an excellent job of reproducing Lipstadt’s New York speech patterns. (In a rare humorous moment, the film points out that Lipstadt’s zesty accent is Queens, not Brooklyn.) Honestly, she sounded like Deborah to me.

But because Deborah Lipstadt, both in life and in the film, is a strong and outspoken individual, I’m sure the audience kept waiting for her to take the conduct of the trial into her own hands. The film shows her meeting her British legal team, who patiently explain to her the way England’s justice system works. No, they don’t want her taking the stand in her own defense. No, they don’t want to call as witnesses the Holocaust survivors who beg to be included as a way to air their own sufferings and those of the loved ones they’ve lost. The lawyers keep begging Lipstadt to trust them, and to keep her mouth shut until the verdict is delivered. That’s why the film’s title, Denial, has a double meaning. It’s only through self-denial, and through bowing to the expertise of her team, that Lipstadt can get the victory that she and the world so badly need.

Published on October 11, 2016 11:59

October 7, 2016

No Crying in Baseball for Vin Scully’s Farewell

Los Angeles Dodgers fans are in mourning. Not for their pennant hopes, although there’s always a chance that they’ll muff the playoffs again this year. But because on October 2, after 67 years, Vin Scully spent his last afternoon in the broadcast booth, doing play by play over the airwaves.

Los Angeles Dodgers fans are in mourning. Not for their pennant hopes, although there’s always a chance that they’ll muff the playoffs again this year. But because on October 2, after 67 years, Vin Scully spent his last afternoon in the broadcast booth, doing play by play over the airwaves.If you haven’t had the pleasure of hearing Vin Scully call a game, you’ve missed out on the poetry of baseball. Scully was scrupulously fair to the players on both teams, and never committed the cardinal sin of talking too much. In fact, there were times (like after a game-changing home run) when he simply let the roar of the crowd tell the story. But his use of the English language was both creative and elegant. An L.A. Times sportswriter who covered his handling of his final game worked into his column some Scully bon mots. One jittery member of the Giants team, he said, “would make coffee nervous.” And a curveball coming from Dodger pitcher Kenta Maeda “floated up there like a soap bubble.” Before the action even got underway, he offered a dramatic description of the San Francisco weather: “The temperature here is 62 degrees, kind of an angry sky at about 6:30 this morning, but it’s softened up a bit . . . and the sky has punctures in it with a little bit of blue overhead.”

Yes, Scully had a sense of baseball’s drama, but he was also a master of its long, storied history. Especially during rain delays, he could spin a great yarn about ballgames past, highlighting both the heroics and the funny moments. Early in his career he worked for a smalltown station where the baseball news came in on a telegraph wire, but this gave only barebones information: how many runs, how many hits per inning. Forced to narrate a game they weren’t actually seeing, he and his colleagues became wildly creative, imbuing each out with a thrilling narrative of its own. No wonder he later had so much fun describing what was really going on.

Scully made a number of movies, usually playing a baseball announcer (natch!), but what he did on the air was certainly entertainment in its purest form. Sure, he sometimes had to shill Farmer John sausage, but what he could accomplish with his voice should serve to remind us of what great radio performers could do, back in the day when television had not yet been born. When we listened to Vin Scully, we felt we were out at the ballpark, feeling the warm sun, smelling the peanuts. In fact, when Dodger Stadium was built, it was engineered so that fans could continue to listen to Vinnie on their transitor radios (remember those?) during the game itself.

I personally encountered Vin Scully twice. As a young pre-teen on my first-ever trip to San Francisco I discovered the Dodgers were in town to play the San Francisco Giants. They were breakfasting at the Palace Hotel, and I was as excited to get Vin Scully’s autograph as I was to collect those of the team’s star players. I remember him as gracious, even if his bacon and eggs were getting cold.

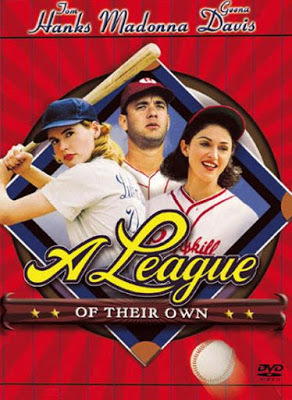

Much more recently, I had to go to a specialized dentist (ugh!). In the waiting room, I saw a familiar-looking face. I wasn’t 100% sure until he answered his phone and I heard that famous voice. I’m sure I reacted, and then Vin Scully winked merrily at me, obviously having gotten this response many times before. I’ll miss you, Vinnie! You’re in a league of your own!

Published on October 07, 2016 13:58

October 4, 2016

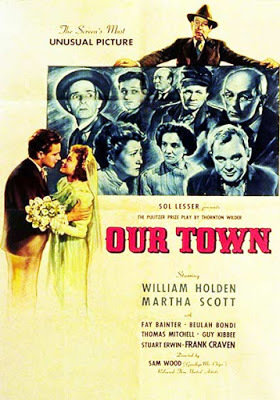

How They Made a Movie Out of “Our Town”

In my day, every high school student knew Thornton Wilder’s 1938 play, Our Town. It was a simple, wholesome depiction of life in a small New England town called Grover’s Corners, spanning the years between 1901 and 1913. Within the play’s cast are all manner of ordinary local folk: a milkman, a constable, two newsboys, a lady who cries at weddings, the local church organist who’s prone to melancholy and drink, and dies a suicide. But the play’s main action involves two local clans. The Gibbs family is headed by the town doctor. The Webb family patriarch is editor of town newspaper. The Webb and Gibbs houses are side by side, and in the course of the play young George Gibbs and Emily Webb fall in love and ultimately marry.

Nothing too unique there, but it was Wilder’s ideas about stagecraft that lifted Our Town beyond the conventional. Today’s literary commentators call Our Town a “metatheatrical” play. This newfangled term points to Wilder’s determination to comment on the nature of theatre by way of the play’s unusual staging. Wilder’s script calls for no realistic sets, just a few chairs and tables on an otherwise bare stage. When George and Emily communicate back and forth from their second-story bedroom windows, the effect is achieved by having them perch on the top of stepladders. The point, of course, is to require audience members to use their imaginations, filling in the details that the set design does not provide.

Helping the viewers along is a character known as the Stage Manager. In theatre parlance, he “breaks the fourth wall,” speaking directly to those who occupy theatre seats. (Traditionally this Stage Manager has been a folksy man smoking a pipe, but I saw a magnificent production in which Oscar-winning actress Helen Hunt took the role.) It’s the Stage Manager’s job to fill us in on the life of the town: its history, its customs, its idiosyncrasies. He introduces characters, and guides us when the story jumps in time, from George and Emily’s high school years to the day of their wedding to the sad day, nine years later, when Emily is buried after failing to survive the birth of her second child. Yes, this is a play that is much concerned with the whole life-cycle, and also with the concept of eternity. A climactic section in the third act takes place in the town cemetery, where the newly-dead Emily is welcomed by the locals who have pre-deceased her. Against their advice, she revisits scenes from her past, then retreats from their everyday wonder, rapturously exclaiming, “Oh, earth, you’re too wonderful for anybody to realize you. . . . Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it?—every, every minute?”

I became interested in the film version of Our Town while reading James Curtis’s biography of production designer William Cameron Menzies. Menzies began making his mark in Hollywood with spectacularly atmospheric sets for films like the original Thief of Bagdad. Our Town posed a very different challenge. Moving far beyond the job of a set designer, he helped the production team decide on a visual approach that would preserve Thornton Wilder’s stylized vision of small-town life. It was he who conceptualized how to handle the Stage Manager, who (instead of leaning against a stage proscenium) would speak to the viewer while casually lounging against a rural fence high above the town. Menzies chose a cluster of stark black umbrellas to set the cemetery scene, and advocated for gauzy filters and unusual angles to show the dead returning to their past haunts. Bravo!

Published on October 04, 2016 10:01

September 30, 2016

August Wilson and "The Cosby Show" -- Black Lives Matter

This week, amid all the hoopla generated by the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture on the mall in Washington DC, I attended a performance of August Wilson’s first great play about the African-American experience. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, set in a recording studio in jazz-age Chicago, first appeared on Broadway in 1984. It won the New York Drama Critics Circle award, and paved the way for a cycle of ten plays that have won many accolades, including two Pulitzer Prizes.

The timing for this revival (which stars Lillias White) seems auspicious. After several unfortunate years of #Oscarsowhite, some of the hottest films now emerging from end-of-summer film festivals feature slices of black life, past and present. Along with the controversial The Birth of a Nation, critics and audiences have responded to the inspirational Queen of Katwe, the tender Loving, and a brave low-budget indie called Moonlight, among others. Denzel Washington now heads a multi-ethnic cast in a remake of The Magnificent Seven, which tops this week’s box office charts. More pertinent, perhaps, is the fact that Washington directs, as well as stars in, an upcoming screen adaptation of August Wilson’s classic baseball drama, Fences. (His wife is played by the great Viola Davis.) It opens on Christmas Day.

The production of Ma Rainey I just saw was directed by Phylicia Rashad, who has a long string of Broadway acting roles to her credit. Though she’s a Tony winner for a recent revival of the classic A Raisin in the Sun, she’s certainly best remembered by most of us as Clair Huxtable, the loving wife of Bill Cosby’s character on The Cosby Show. This sitcom of course ruled the airwaves from 1984 through 1992. It’s never easy to move on from a long-lasting hit, and I admire Rashad for proving that she can do more than banter with a TV spouse and TV children.

One of many landmark aspects of The Cosby Show was that it helped a nation fall in love with an upper-middle-class African American family. The patriarch played by Cosby was an obstetrician (and also the son of a prominent jazz musician); wife Clair was an attorney. Their five smart, sassy kids kept them hopping, and the nation got a chance to meet black parents who faced the same joys and woes as their white counterparts. So The Cosby Show, though often very funny, was both a comedy and a civics lesson, with dad Cliff Huxtable sometimes the butt of the joke.

How times have changed! We now know (or at least suspect) things about Bill Cosby that aren’t so pleasant. The man we’ve been hearing about lately, from a long list of women with tales of drugging and rape, seems to have taken advantage of his worldly success in ways disturbing to imagine. As a weekly visitor in the nation’s living rooms, he had power, and he apparently used it in unsavory ways.

Which brings me back to August Wilson’s play, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. Its title character, an actual historical figure, was a jazz great with a following among African-American record-buyers. That’s why her (white) manager and the (white) head of a record label are willing to put up with her shenanigans, which involve showing up late for recording sessions and making outrageous demands. She sasses them, but saves most of her venom for those beneath her, the musical sidemen who back up her singing. Power corrupts, and those on the bottom are the ones who suffer: too bad a self-styled educator named Dr. William Cosby had to teach us that lesson.

Published on September 30, 2016 11:56

September 27, 2016

William Cameron Menzies: A Production Designer Who Has Gone with the Wind

When we think about the landmark film production of Gone With the Wind, most of us conjure up images of Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh, Olivia de Havilland and Hattie McDaniels. If we’re up on film history, we remember the film’s imperious producer, David O. Selznick, as well as a revolving cast of directors that included George Cukor and Victor Fleming. But the name William Cameron Menzies doesn’t readily spring to mind. My colleague Jim Curtis’s exhaustively researched 2015 book, William Cameron Menzies: The Shape of Films to Come , aims to change all that.

Menzies began his career as an art director at the tail-end of the silent era. On such early sound films as 1933’s all-star Alice in Wonderland and the futuristic 1936 Things to Come, he used his artistic talents not only to plan appropriate settings but also to lay out camera moves and action sequences. Through volumes of elaborate sketches that are the forerunners of today’s storyboards, he conceptualized the visual aspects of many productions. He himself described his mandate: “As a production designer, it is my job to dramatize the mood of a picture and to keep it ‘in character.’ This is done simply by coordinating every phase of the production not covered by dialogue and action of the players.”

That, of course, was a huge responsibility, and Menzies’ family life inevitably suffered. Still, those in the know fully recognized his genius. Selznick insisted he be part of the Gone With the Wind team, and later granted him the brand-new “production designed by” credit to reflect the broad scope of his services. Ironically, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences did not recognize the title of production designer when it came to handing out Oscars. That’s why the art direction Oscar for Gone With the Wind (one of eight won by the film) went solely to Lyle R. Wheeler. Happily, at the Oscar ceremony Menzies was awarded a special plaque recognizing his “outstanding achievement in the use of color for the enhancement of dramatic mood” in the film. (He had earlier nabbed a competitive Oscar for the 1928 silent, Tempest, but won no awards in his later career, which ended with an associate producer credit on 1956’s Around the World in Eighty Days.)

The Academy’s recognition of Menzies’ work on Gone With the Wind focused on his pioneering use of color. For instance, he deliberately chose “severe red skies & indigo backings” to punch up somber scenes like the burning of Atlanta. When it came to filming the moment in which Melanie gives birth, the challenge was to suggest the anguish of the experience while not running afoul of the MPAA’s Breen office, which frowned on depicting outright pain and suffering. Menzies’ solution was to choose angles “of stark black and sharp, knifelike patterns of yellow, no light falling on the shutters or the human figures in the foreground, simply a white backing reflecting the colored glare of flood lamps through the slits.” He intuited that orange was a hot color, while black could suggest violence. The combination of the two colors suggested both a steamy afternoon and the violence of childbirth.

Menzies’ contributions to Gone With the Wind also included the iconic use of a (fake) tree in the foreground to add drama to the shot of Gerald O’Hara showing his daughter the land that is her birthright. When he needed towering shadows of Leigh and de Havilland, he got the effect by using doubles who were required to move in unison with the two actresses in the foreground of the shot. Who knew?

Speaking of Atlanta, I encourage all working writers and journalists to be aware of the American Society of Journalists and Authors’ regional conference in that fair city on Saturday, November 5. There’ll be loads of practical info on how to further your career. Early bird sign-up rates end soon. Here’s the link.

Published on September 27, 2016 11:45

September 23, 2016

Curtis Hanson: An L.A. (and Roger Corman) Story

With the passing of Curtis Hanson, we’ve lost another great director. He recently died in his Hollywood Hills home at the all-too-early age of 71. Hanson is best known for directing 1997’s L.A. Confidential, a film noir thriller based on James Ellroy’s novel exploring police corruption in the City of Angels, circa 1950. Hanson called L.A. Confidential his most personal project, because Ellroy was “telling a story set in the same city that I grew up in and dovetails with certain ambitions that I’ve had in terms of telling an L.A. story.” L.A. Confidential would be nominated for seven Oscars, including Best Director and Best Picture. Kim Basinger won an supporting actress Oscar for her femme fatalerole, and another went to Hanson, along with Brian Helgeland, for their adapted screenplay. Too bad the film was up against Titanic.

Before he took the helm of L.A. Confidential, Hanson had directed such successful nail-biters as The Hand that Rocks the Cradle (1992) and The River Wild (1994). He also succeeded with Wonder Boys (2000, based on Michael Chabon’s novel of academic life), and the surprisingly appealing 8 Mile (2002), about the rise of rapper Eminem. Though Hanson could delve into a female relationship story (In Her Shoes, 2005), his natural bent seemed to be toward the dark and violent side of life. That’s hardly surprising: he emerged (like Titanic’s James Cameron and so many more of Hollywood’s rising directors) from the colorfully grim world of Roger Corman.

Hanson first came to the attention of my former boss in 1970 when he wrote the screenplay for The Dunwich Horror. This variation on a supernatural tale by H.P. Lovecraft was directed by longtime Corman art director Dan Haller for Corman’s former movie home, American International Pictures. (Corman himself served as executive producer.) This was the era when Corman was moving into his own company, New World Pictures. Hanson wrote and directed for Roger a 1972 film called Sweet Kill. IMDB describes this as “the story of a psychotic maniac who literally ‘loves’ women to death.” But despite the lurid subject matter, audiences weren’t enticed. Typically, Roger asked Hanson for additional sex scenes, then retitled the flick The Arousers.

My own sojourn at New World Pictures came just after Hanson’s time, though I remember tabulating bookings for The Arousers in drive-ins across America. During my New World stint, however, I rubbed shoulders with other young directors (like my buddy Steve Carver) who began notable careers by making Corman genre movies, usually thrillers or horror flicks, on the lowest possible budgets. Monte Hellman was no youngster when he returned to New World to shoot Cockfighter. But I worked closely with Paul Bartel, who was tapped to direct the cult classic Death Race 2000 and would move on to the lurid Eating Raoul as well as much larger studio projects. Jonathan Demme, who directed his first film, Caged Heat, for Roger in 1974, was a fixture around the New World offices, long before he became a major Hollywood player and an Oscar winner for a dark and twisted project on a grand scale: Silence of the Lambs.

Corman protégés from an earlier era included Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, and Peter Bogdanovich. After I left New World (but before I returned to Corman’s Concorde-New Horizons), the directing career of Ron Howard was launched. I knew Joe Dante as a New World editor and trailer cutter, but didn’t suspect he’d blossom into a director on the strength of Corman’s Piranha. For Joe, as for other Corman folk, cheap genre movies led to big careers.

If you want to know more about Roger Corman and his circle, do check out my acclaimed insider biography, Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers. Now available in paperback, ebook, and audiobook form.

Published on September 23, 2016 11:17

September 20, 2016

David Cronenberg: Maps to Scary Places

I’m not sure what there is about the sturdy, Biblical name David that encourages perverse thoughts, but Movieland seems to be studded with writer-director Davids who consistently look on the dark side. David Lynch started with creepy works like Eraserhead, won widespread acclaim for Blue Velvet, achieved cult status with Twin Peaks, and continued off the beaten path with such disturbing films as Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive. David Fincher is perhaps best known for the not-so-grim The Social Network, but he got his hands bloody with flicks like Se7en,Fight Club, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, and Gone Girl.

And then there’s David Cronenberg, who has made a career out of exploring subjects that are eerie and gruesome. Cronenberg is Canadian, which I believe is supposed to make him mild-mannered and polite. Which he may well be, in person, but his mind works in peculiar ways. Maybe that’s why his favorite literary influences are Vladimir Nabokov and William S. Burroughs, whose bizarre and unfilmable Naked Lunch he once tried to adapt for the screen. Given his filmography, it’s no surprise to learn that his favorite school subject was science, especially botany and lepidopterology. (This field, the study of butterflies, would certainly put him in sync with Nabokov, an expert in the field.)

I was first introduced to Cronenberg via his ghoulish remake of The Fly (1986), starring Jeff Goldblum as an out-of-control biologist. Intrigued—and, as a Roger Cormanite, always on the look-out for low-budget ideas we could steal—I dipped back into the Cronenberg canon to discover The Brood (1979), full of psychological and biological oddities that end in a shocking conclusion. Then came Dead Ringers (1988), a cold, clinical tale involving Jeremy Irons as twin gynecologists who share a perverse interest in women who are beautiful, inside and out. Not a lot of laughs in that one.

I was impressed by Cronenberg’s riveting, though slightly more conventional, film approach to the graphic novel, A History of Violence (2005). But I’m thinking about Cronenberg right now because I just caught up with his most recent feature, 2014’s Maps to the Stars. This film has won its share of international awards, many of them for the lead performance of Julianne Moore as Havana Segrand, a troubled child of Hollywood. Written by Tinseltown laureate Bruce Wagner, it has its share of mordant humor, based as it is on the questionable priorities of film stars and their entourage. But it seemed odd to me that Moore’s performance was singled out by the Golden Globes folks as a nominee for Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Comedy or Musical. This film is by no means a musical, and I’d be hard pressed to think of it as a comedy, given that it encompasses arson, poisoning, strangulation, and the shooting death of an entirely innocent creature. I guess it could be considered comic in the Shakespearean sense because it ends (sort of) in a wedding. And that’s all the spoilers I’ll dare to mention.

Suffice it to say that there’s an expert cast, led by Moore as well as John Cusack (as a pop psychologist to the stars), Olivia Williams as his wife, Evan Bird as their cocky child-star son (now appearing in a sequel to Bad Baby-Sitters), Mia Wasikowska as the new girl from Jupiter, and Robert Pattinson as a Hollywood hopeful. The horror elements of the story don’t necessarily add up, but they’re creepy indeed. And the swank venues inhabited by the Hollywood rich are reproduced with a cold, clear eye. That’s good for a shudder, at least.

Published on September 20, 2016 16:12

September 16, 2016

Running on Empty with Marathon Man

The story of The Graduate opens with naïve young Benjamin Braddock on his first day back from four years of college. At a lavish party thrown by his proud parents, the predatory Mrs. Robinson approaches Ben in his boyhood bedroom and lights a cigarette. When he can’t provide her with an ashtray, she smiled condescendingly and says, “Oh yes, I forgot. The track star doesn’t smoke.”

In The Graduate, Hollywood newbie Dustin Hoffman revels in his role as a classic high-achiever, one who has earned top grades, presided over the debating club, served as managing editor of the campus newspaper, and won an impressive scholarship for graduate study. He is also the captain of the cross-country team, and so he can legitimately be called a track star. The film was a runaway hit, adored by audiences all over the world. Most critics too were impressed, although some quibbled that the tongue-tied young man whom Hoffman portrays is not entirely convincing as a scholar and (especially) an athlete. It’s true that the film’s several running scenes (like the famous one in which Ben races to the church to stop the wedding of his beloved) don’t validate our sense of Benjamin’s stellar athleticism. Still, all of us who bought into the character as a perfect embodiment of our own Sixties preoccupations were willing to accept Hoffman’s portrayal as the real deal.

Though I’ve spent several years of my life researching and writing about The Graduate, I didn’t realize until now that in the 1976 film Marathon Man Hoffman (almost 40 but still with a youthful look) plays another runner. His Thomas Babington (“Babe”) Levy, a graduate student in history at Columbia University, has been shaped by his father’s disgrace in the McCarthy era. Though he’s fond of his older brother (Roy Scheider), he has no way of knowing about Scheider’s undercover political activities. As respite from his own academic obligations, Babe trains in New York’s Central Park to run marathons. And his long-distance running skills will come in handy when he is caught up in a mysterious plot involving Nazi fugitives, his brother’s double-agent henchman, and a whole lot of illegally acquired diamonds.

William Goldman, the famous Hollywood screenwriting guru, wrote the screenplay for Marathon Man, adapting his own most commercial novel. I’ve read that he was inspired by the idea of situating Nazis in an intensely Jewish city like New York. The director was another top-of-the-line Hollywood talent, John Schlesinger, not many years removed from directing Hoffman on the streets of New York in Midnight Cowboy. Conrad Hall’s cinematography puts us where the action is (the film made pioneering use of the Steadicam for its chase scenes). And the #1 villain, a sadistic former Nazi dentist, is played by none other that Laurence Olivier, almost 70 and in frail health, but still able to wield a dental drill like nobody’s business. “Is it safe?” he asks, hovering over a terrified Hoffman. Clearly, in his skilled hands no one is really safe. And on the heels of this film, whole generations have been reluctant to schedule their dental checkups.

I enjoyed this thriller until just past the midpoint, when I realized the plot made very little sense. That’s what happens, I believe, when a novel stuffed full of twists and turns is condensed into a two-hour film. Something’s got to give, and it’s usually plot logic. Though Marathon Man was highly popular, it only nabbed one Oscar nomination, for Olivier. But Hoffman—looking for a father figure—found in the elderly English actor a marathon man to admire and emulate.

Published on September 16, 2016 12:48

September 13, 2016

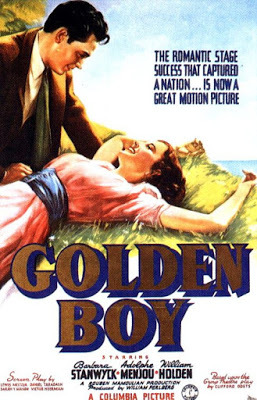

Fiddling Around with “Golden Boy”

It seems that there’s always a boxing movie or two in theatres. At the moment, we have Hands of Stone, with Robert De Niro playing not a boxer (see Raging Bull) but the trainer of real-life boxer Roberto Duran. Last year there was Creed, with Sylvester Stallone graduating from being Rocky the prize-fighter to Rocky the trainer of his former opponent’s son. Also last year, Jake Gyllenhaal bulked up to play a boxer in Southpaw. It was not so long ago that Christian Bale won an Oscar for The Fighter (which also featured Mark Wahlberg), while Russell Crowe impersonated boxer James Braddock in Cinderella Man. Then there are oldies like Body and Soul (1947); Kirk Douglas achieved stardom by playing the corruptible Midge Kelly in the 1949 boxing film, Champion, which was producer Stanley Kramer’s first big Hollywood achievement.

But I’m here to write about the granddaddy of them all, 1939’s Golden Boy, based on a Broadway hit drama by Clifford Odets, who knew a great deal about downtrodden lives in New York City during the Depression era. The premise, approached with high seriousness on the screen, sounds almost comic in the telling: a young man with a talent for boxing can’t decide whether or not he’d really rather be playing the violin. Several major characters are determined to help him make up his mind. On the side of music and an impoverished but noble life in the arts is Joe Bonaparte’s Italian immigrant papa (Lee J. Cobb), who agrees with Joe’s sentiment that “a prizefight is an insult to a man’s soul.” The other point of view is represented by Joe’s new manager, Tom Moody (Adolphe Menjou), along with Moody’s fiancée, a self-styled “dame from Newark” played with gusto by Barbara Stanwyck. These two are quick to point out that success in the ring can lead to money and respect . . . not to mention the possibility of Stanwyck’s favors.

The pivotal role of Joe Bonaparte -- who’s got to look convincing both punching out opponents in the ring and gently fiddling Brahms’ Cradle Song (“Lullaby and good night . . “) in his father’s living room -- was won by a Hollywood newcomer named William Holden. In a word, he is sensational. The part calls for him to have a mean streak, as well as a side that’s profoundly gentle, and he manages to persuade us that this character contains both possibilities. The cast is also full of colorful stage types: a dapper gangster (Joseph Calleia); a Jewish socialist buddy of his father (William H. Strauss); Joe’s giggly married sister (Beatrice Blinn) and her always-hustling spouse (Sam Levene). Directing the film is a Broadway and Hollywood legend, Rouben Mamoulian. Mamoulian’s illustrious career included the stage premieres of Porgy and Bess (1935), Oklahoma! (1943) and Carousel (1945). As a movie director, he was responsible for 1929’s Applause. This early musical, starring Helen Morgan, was a landmark in the development of modern camera and sound technologies. The last film Mamoulian directed was also a musical, 1957’s Silk Stockings, starring Fred Astaire and Cyd Charisse. (He also was fired from, or resigned from, some other notable films: 1944’s Laura, 1959’s film version of Porgy and Bess, and the infamous Elizabeth Taylor/Richard Burton production of Cleopatra).

Mamoulian was born in Tiflis (now Tibilisi), Georgia, in 1897, when it was still part of the Russian Empire. He survived until 1987, when he died at age 90. I visited him in his Beverly Hills home circa 1978. The place was crawling with cats . . . but that’s a subject for another day.

Published on September 13, 2016 12:58

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers