Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 91

February 24, 2017

Guys into Gals: Cross-Dressing for Success

Who could have guessed that our politicians would become so interested in bathrooms? First in North Carolina and now in Texas, politicians are vying to force transgender men and women to use the restrooms matching the gender status on their birth certificates. Why this hubbub? The politicos are convinced that some men might choose to put on dresses in order to assault women in the privacy of bathroom stalls.

Frankly, I can’t see would-be rapists getting quite so creative. But the whole issue has reminded me that in more innocent times a man dressed up as a woman was a matter of high (or maybe low) comedy. Drag is, in fact, an ancient theatrical tradition, dating back to the days when all actors were male. (That’s the way it was in Shakespeare’s time, Gwyneth Paltrow’s role in Shakespeare in Love notwithstanding.) After women were allowed onto the stage in eighteenth century England, there remained a British fondness for the “dame show,” featuring a large middle-aged male comically dressed as a buxom maternal type. The “dame” still shows up, particularly in the holiday season, in English-style pantomime. And then of course there’s naughty Dame Edna, as flamboyantly portrayed by an Australian actor, Barry Humphries.

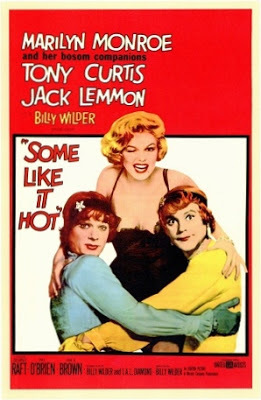

Americans have often found this kind of cross-dressing funny too, especially when the dress is worn by a suave leading-man type like Cary Grant. (See Cary decked out in Katharine Hepburn’s marabou-trimmed négligéein one of his most hilarious films, Bringing Up Baby). And in this context how can we forget Billy Wilder’s comic masterpiece, Some Like It Hot? That, of course, is the story of two very male musicians (Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis) who try to flee from some dangerous Chicago mobsters by disguising themselves as members of an all-girl orchestra heading for a Florida gig. To keep up the charade, they find themselves in temptingly close quarters with a bevy of musical cuties, including band singer Marilyn Monroe. The extended joke becomes increasingly hilarious as Lemmon’s character, “Daphne,” finds himself wooed by a highly persistent millionaire, Osgood Fielding III (Joe E. Brown). “Daphne” tries in vain to fend off Fielding’s advances, which include a proposal of marriage. As every cinephile is well aware, Fielding won’t take No for an answer. When Lemmon’s character, having tried every other ploy, removes his wig and announces he’s a man, Fielding simply shrugs and offers the immortal line, “Well, nobody’s perfect.”

Some Like It Hot was obviously in someone’s mind when TV execs launched Bosom Buddies in 1980. This sitcom, which lasted until 1982, featured newcomers Tom Hanks and Peter Scolari as two young ad men who – having lost their New York apartment – disguise themselves as women in order to move into the low-rent Susan B. Anthony Hotel. Hanks’ innocent charm led directly to his leading role in Splash, and the rest is movie history.

But in 1980 future Texas legislators were more likely watching a dark little Brian De Palma film, Dressed to Kill, in which cross-dressing is an evil (and eventually deadly) secret. Cross-dressing and transgender issues (which of course are not exactly the same thing) show up far more sympathetically in 1992’s The Crying Game, which made a shocking secret out of one character’s biological identity. And Hilary Swank won an Oscar for the true-life story of Brandon Teena in 1999’s Boys Don’t Cry. In that film, Swank’s character struggles with the fact that she considers herself male, despite biological evidence to the contrary. She ultimately pays a high price. But I don’t recall her being punished for daring to use a men’s bathroom.

Published on February 24, 2017 15:28

February 21, 2017

The Unsullied Tom Hanks

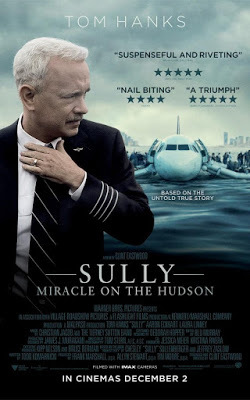

Next time you’re taking a trip and you spot Tom Hanks at the helm or in the cockpit, beware! He’s got a good, steady hand on the tiller, but the guy has terrible luck. He’s in charge of an American cargo ship off the coast of Africa (Captain Phillips), and the next thing you know, it’s attacked by Somali pirates. He becomes the lead astronaut in a mission to the moon, and because of a mechanical glitch nearly gets lost in space (Apollo 13). In 2016’s Sully, he’s a veteran airline pilot whose US Airways plane out of New York City—with 155 people aboard—is unexpectedly disabled by a flock of Canada geese. Though he makes a successful (and unprecedented) landing in the Hudson River, he then faces scrutiny by the National Transportation Safety Board that nearly grounds him for good. (More bad luck: ABC’s website announces he’s been nominated for an Oscar for Sully . . . but he hasn’t.)

Even when Hanks is a passenger, bad things happen. Traveling for his job as a FedEx systems engineer, he faces a weather-related crash off the coast of Malaysia. A life raft deposits him on a nameless tropical island where he survives for four years with only a volleyball for company. When he finally gets back to Memphis, he discovers his long-term fiancée has married his dentist. Maybe he had the right idea back in 1984, where as a skinny and curly-haired young man newly elevated from TV sitcomland, he fell in love with a mermaid and followed her into the briny deep. I’d hope our Tom faced better odds under the sea than he later did when traveling on the water and in the air.

There’s one time when Tom was undeniably lucky. When Ron Howard, early in his directing career, was casting Splash, his romantic comedy about a mermaid who washes up in Manhattan, Howard’s assistant Louisa Velis suggested he consider Hanks, because she enjoyed his work on the crossdressing sitcom, Bosom Buddies (1980-1982). At first, Hanks was up for the part of the hero’s devil-may-care brother. But both John Travolta and Michael Keaton passed on the leading role, as did comic actors Bill Murray, Chevy Chase, and Dudley Moore. Ultimately, Hanks nailed the audition and got the job. Howard says now that what he discovered in Hanks was an ability to play the film’s comic rhythms, “but not sell the integrity or the honesty of the moment down the river.” Hanks himself remembers that once he got the part, “literally, my life was changed forever.”

Tom Hanks’ career tells us something about stardom, Hollywood-style. Though a gifted actor, he’s bigger than the roles he plays, and we in the audience can’t help responding to our sense of his personality as well as to his characterizations. I doubt we’d buy Hanks as an exotic foreigner, and his bad-guy roles are rare. (Even when he plays a hitman in Road to Perdition, he’s a good-hearted hitman.) What we see in Tom Hanks is a quality he shares with Jimmy Stewart: the amiability of an American everyman. Stewart played light comic parts (Harvey, The Philadelphia Story), inspirational roles (It’s a Wonderful Life, The Spirit of Saint Louis), and eerie dramas (Hitchcock’s Rear Window and Vertigo). Whatever sort of role he played, we were on his side.

For Tom Hanks we tend to feel the same sort of trust, whether he’s making a film or living his life. Even if his luck with modes of transportation is lousy, maybe he’s the Mr. Smith we’d like to see in today’s Washington.

Published on February 21, 2017 12:10

February 17, 2017

Denzel Washington: Don’t Fence Him In

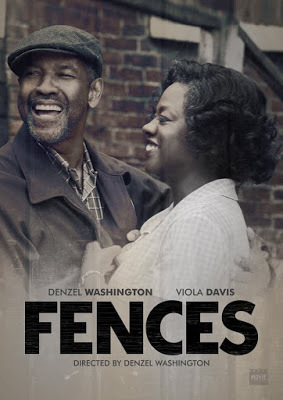

Having just seen Denzel Washington’s production of Fences at my local multiplex, I’m collecting my thoughts about the film’s Oscar chances. Fences, of course, is part of August Wilson’s so-called Pittsburgh Cycle of ten plays about the African-American experience. It reached Broadway in 1987, in a production toplined by James Earl Jones as Troy Maxson, a sanitation worker who once dreamed of baseball stardom. That production won Wilson and company a slew of Tony Awards, plus a Pulitzer prize.

Wilson was long ago approached by Hollywood regarding Fences. He made it clear he would never permit the play to be filmed unless a black director was at the helm. Still, before his death in 2005 at age 60, he wrote a screen adaptation of his stage play. The very enterprising Scott Rudin (Ex Machina, Captain Phillips) suggested Denzel Washington bring Fences to the screen, and this idea evolved into a much-lauded 2010 Broadway revival, starring Washington as well as Stephen McKinley Henderson, Mykelti Williamson, and the magnificent Viola Davis. All four have ended up in Washington’s film version, along with some excellent younger actors.

So how do I feel about Fences as a movie? It’s a powerful representation of August Wilson’s theatrical world. It’s valuable in bringing to audiences who’ve never seen a Wilson play an articulation of his motifs, like the impact of the past upon the present and the role of racism in crushing (or cruelly twisting) the black man’s spirit. But despite its Oscar nomination as one of the year’s best films, Fencesremains at heart a play. And though August Wilson earned a posthumous nomination for adapting his own stage work into a screenplay, a quick look back at the original suggests to me that not much has been changed to take advantage of the screen’s unique properties. A Wilson play is all about language, its ebbs and its flows. Wilson characters deliver lengthy speeches full of poetic rhythms that can make them resemble arias. Yes, director Washington has added some visuals: street scenes, a glimpse of Troy Maxson and his crony Bono at work on a garbage truck. But mainly we have static locations (chiefly the crammed yard of Maxson’s Pittsburgh row house) and far more talking than most movies can handle. It’s brilliant talking, wonderfully executed, but this didn’t feel like a movie to me.

I also have mixed emotions about giving acting awards to performers who’ve just finished playing the identical roles on stage. As strong a performance as Washington gives, he’s already been duly rewarded with a Tony. Yet there’s talk about him becoming the new frontrunner for a Best Actor Oscar, given that he triumphed at the SAG Award ceremony over Casey Affleck of Manchester by the Sea. As always, external forces may be at work here. Affleck has some messiness in his past (accusations of sexual harassment) that may make some squeamish about supporting him, despite the stellar nature of his performance as Lee Chandler. And it’s tempting to see this shaping up as a year with an #Oscarsoblack tinge. But Denzel Washington isn’t lacking for Oscars on his mantel, and I’m personally in awe of Affleck’s subtle work. Of course, I don’t have a vote.

Viola Davis is another story. I could argue, certainly, that what she gives is a Best Actress performance. Putting her in a Supporting Actress category is slightly unfair to her fellow nominees, like Michelle Williams and Naomie Harris, who do exceedingly well with much less screen time. But Davis has been due for years, and it seems her moment has finally come.

Published on February 17, 2017 09:08

February 14, 2017

Humorous or Haunted: Will the Real Shirley Jackson Please Stand Up?

Some readers think of Shirley Jackson as a highly perverse writer with a taste for the macabre, the author of such creepy stories as “The Lottery.” (Stephen King is a serious fan.) Others remember her as a happy homemaker, someone who chronicled the misadventures of her four kids with both exasperation and amusement. Jackson’s Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons, highly popular in their day, made her a kind of forerunner to Jean Kerr (Please Don’t Eat the Daisies) and Erma Bombeck, both of whom wrote about domestic life with love and glee. I’ve just finished a fascinating new biography by Ruth Franklin. It’s called Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, and it argues that Jackson’s spooky predilections and her affectionate regard for her brood reveal two sides of a very complex personality.

Shirley loved her kids and her kitchen. In an era (the Fifties) when being a housewife was considered a high calling, she excelled at whipping up creative meals, tending the family pets, and stimulating her children’s already-active imaginations. On the other hand, surrounded by her busy brood and a husband (critic Stanley Edgar Hyman) who was not a reliable helpmeet, she had to fight desperately to find time to sit down and write, an obligation that was all the more necessary because she was the family’s financial mainstay. Nor did her own inner resources make life easier: she hated her physical appearance and fought a losing battle to please her stern, unyielding mother. Later in life (she died of heart failure at the all-too-early age of 48) she struggled with agoraphobia. Which meant that for months at a time she was reluctant to stir from her large and ramshackle Vermont house. Given her penchant for writing haunted-house stories, her neurotic fear of leaving her own hearth and home speaks volumes.

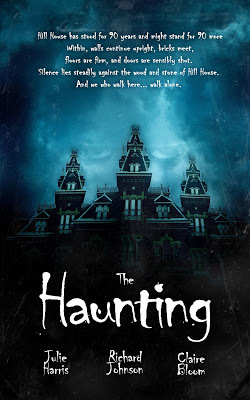

In movie terms, Shirley Jackson is best know for The Haunting of Hill House, the 1959 novel that was Hollywoodized as The Haunting (1963). Directed by Robert Wise soon after his 1961 triumph with West Side Story, it’s an elegant black-&-white depiction of psychological terror, focusing on the effectively fragile Julie Harris. But the main character must be – and is – the huge, gaudy, and thoroughly enigmatic Hill House, in which a small clutch of psychic investigators plan to stay the night. Wise comes from a background as a film editor (he worked on Citizen Kane), and his startling shots do convince us that evil is afoot. The Haunting has been compared to Jack Clayton’s 1961 The Innocents, a movie that shook me to my core when I was a teen. For me The Haunting is not nearly so disturbing, though—despite small departures from Jackson’s original story—it remains an effective exploration of the ambiguity of evil. (I haven’t seen the big-name 1999 remake, but it’s been universally panned.)

After finishing the Jackson biography, I was moved to read more of Jackson’s own writing. I was promptly floored by the power of her last completed novel, We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962). This eerie experiment in first-person narration takes us into the mind of a young girl with a very unusual perspective on life. Once again there’s a disturbing old mansion, and two unforgettable female characters who live in a world of their own making. (Yes, it sounds a bit like the real-life Grey Gardens.) Upon reading it, I thought it was ripe for film adaptation . . . then discovered that a new British film of the novel will be released this year. Will it do Jackson justice? We shall see.

This isn’t much of a Valentine’s Day post, I realize, but some might argue that Jackson’s personal dichotomy illustrates what marriage is all about: two parts domestic delight and one part horror. Not that I’m speaking personally, of course.

Published on February 14, 2017 11:57

February 10, 2017

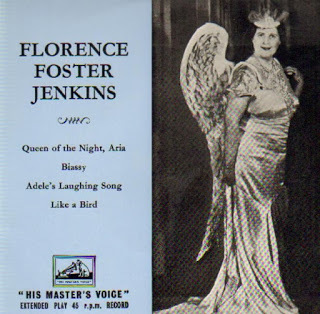

Florence Foster Jenkins; Nevertheless, She Persisted

Meryl Streep, who spends her private life far from Hollywood, is not generally considered a rabble-rouser. She comes across as a solid citizen, who has lately been gravitating toward no-nonsense biographical roles, like Julia Childs and Margaret Thatcher. (For portraying Thatcher in The Iron Lady, she won her third Academy Award in 2012, out of a whopping 20 nominations.) Streep’s track record notwithstanding, she’s lately been vilified in some quarters as “overrated.” That’s certainly questionable, but no more surprising than her choice of her most recent Oscar-nominated role, that of socialite Florence Foster Jenkins.

Like Childs and Thatcher, Florence was a real person. She lived from 1968 to 1944, when she died of a heart attack at age 76, just after her Carnegie Hall debut. So many of Streep’s recent characters (like Childs, Thatcher, and Vogue editor Anna Wintour, whom she essentially played in The Devil Wears Prada) are women of strength and talent. They may have their dark side, but they remain leaders and visionaries. Florence, though, is a bird of a different feather. A Manhattan heiress, she used her considerable wealth to promote the art of music—but also to showcase her own highly unmusical yowlings. Abetted by friends, sycophants, and a supportive common-law husband (played in the film by a charmingly ambiguous Hugh Grant), she insisted on performing difficult coloratura arias while wearing extravagant costumes of her own devising. Descriptions of her concerts are colorful: one onlooker wrote that a Jenkins performance “was never exactly an aesthetic experience, or only to the degree that an early Christian among the lions provided aesthetic experience; it was chiefly immolatory, and Madame Jenkins was always eaten, in the end.” Nonetheless, despite her total ineptitude, she had an unlikely array of fans, including such music-world greats as Cole Porter, Enrico Caruso, Gian Carlo Menotti, and Lily Pons.

No one is quite clear on the extent to which Florence was deluded about her own abilities, or the lack thereof. In a scene that follows hard upon her raucous Carnegie Hall performance, Streep utters a phrase that Florence apparently spoke in real life: "People may say I can't sing, but no one can ever say I didn't sing." This statement implies a degree of self-awareness that makes the story of Florence Foster Jenkins a more intricate one than it first appears. It’s also true that Florence can be viewed as a victim, albeit one who found a way to rise above the very real pain of her existence. At age 17, without her father’s consent, she had eloped with Dr. Frank Thornton Jenkins, only to discover that he’d given her syphilis. Ravaged by the disease and by the quack medical treatments of the day, she may have developed (among other things) a hearing loss that prevented her from knowing the extent of her assaults on her listeners’ eardrums. Streep’s portrayal finds a way to make her self-delusion—if that is what it was—heroic. She shows such delight in her own eccentric performances that it’s hard to imagine denying her that pleasure.

Still, it’s worth musing on the gender implications of this story. A woman who believes she has talent and insists on unleashing it can be considered endearing. (It is, in fact, a familiar stereotype: just think of Jean Hagen’s lovably dopey movie star, Lina Lamont, in Singin’ in the Rain.) But imagine a story about a talentless man who puts himself on public display. Like Laurence Olivier’s over-the-hill vaudevillian character in The Entertainer, he would surely be considered tragic. Only in women is incompetence seen as adorable.

Published on February 10, 2017 10:44

February 7, 2017

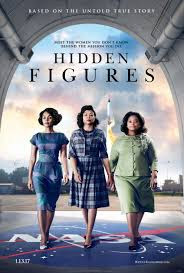

“Hidden Figures” – Lifting Us Toward a Greater America

Hidden Figures is exactly what we need right now -- a comfort film. In an era when a promise to “make America great again” has led to brutally divisive rhetoric on many sides, it’s cheering to see a movie that celebrates the coming together of all sorts of people in pursuit of a grand goal: putting Americans into space. This true story of three black female NASA employees, gifted in mathematics and what we today call STEM, is a heartening reminder that when we’re able to look past ethnic, gender, and religious differences, not even the sky’s the limit.

In Hidden Figures the cast of characters is (as a scientist might put it) binary. In and around Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia circa 1960, you were either white or black, either male or female. Brief screen-time is given to a thickly-accented Jewish survivor of the Holocaust who now is working overtime to put astronauts aloft via the Mercury program. But among the space scientists, and also among the crowds gathered to watch and cheer, there seems to be no such thing as a Latino, a Middle Easterner or an Asian. Probably this reflects the reality of Virginia in that era, essentially the same one glimpsed in the equally excellent film Loving, which focused on the Supreme Court decision that overturned state bans on interracial marriage. In any case, Hidden Figures fundamentally belongs to three black actresses--Taraji P. Henson, Octavia Spencer, and Janelle Monáe—who are so vibrant and appealing that it’s no wonder this film received the prestigious SAG award for its ensemble cast. (Mahershahla Ali, an Oscar favorite as the sympathetic drug dealer in Moonlight, here switches gears to play a straight-arrow love interest.)

Each of the three women at the center of Hidden Figures has impressive intellectual gifts. They are all ready, willing, and able to provide key technical support for a fledgling U.S. program that is desperate to overcome the Soviet Union’s head-start in space. But because of the color of their skin the three are relegated to a separate unit in a separate building. It is only when the NASA chiefs become desperate (in a pre-computer age) for expert mathematical help on the first Mercury launch that Katharine Goble (Henson) is ushered into the all-white, all-male domain over which Kevin Costner presides. Still, despite her elevation, she faces constant bias, dramatized by the head engineer’s refusal to allow her name on key reports and especially by her daily races to a distant “colored” bathroom when nature calls.

The bathroom issue, of course, reflects the Southern segregation policies of the time. But in many ways, all women were at a marked disadvantage at Langley (and probably throughout NASA) in this era. They were valued as support staff, but were traditionally barred from strategic briefings and kept far from the inner workings of the space program. Women back then were assumed to be wives and mothers, waiting at home for their hard-working spouses. Those who snagged NASA jobs were herded together in their own divisions, and had to adhere to strict codes: modest dresses of a certain length, high heels, no jewelry other than a wedding ring and a modest strand of pearls. (Essentially, they were dressed not for long hours of work but for a tea party.) The supervisor character played by Kirsten Dunst hints at what happens when a smart woman is undervalued: she makes life miserable for those even further down the chain of command.

But it’s the black trio you’ll remember: women who prove there’s no color bar in space.

Published on February 07, 2017 12:57

February 3, 2017

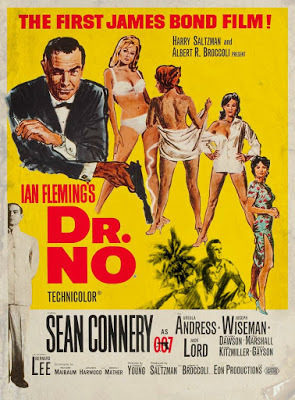

James Bond’s Richard Maibaum: Stirred, Not Shaken

If you grow up in SoCal, you’re apt to know some movie folk. When I was a small tyke living in a Hollywood apartment complex, my playmate’s father was a long-time cameraman at Paramount, a man who’d worked on such classics as Double Indemnity and Sunset Boulevard. And just recently I met someone whose dad was a studio carpenter. His claim to fame? For Cecil B. De Mille’s The Ten Commandments he constructed the “stone” tablets that Moses carried down from Mt. Sinai.

Then there’s my friend, Matthew Maibaum, who descends from genuine movieland royalty. Matt’s father, Richard Maibaum, contributed to the scripts of over fifty Hollywood movies, including Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent, The Pride of the Yankees, and the 1949 Alan Ladd version of The Great Gatsby. But his real claim to fame derived from his long association with a certain famous secret agent. It all began over ice cream at Wil Wright’s in Hollywood. His friends Albert (“Cubby”) Broccoli and Harry Saltzman had enjoyed some success making low-budget war movies in England. Now they had a new idea. Broccoli handed Maibaum a paperback novel by a failed British spy named Ian Fleming, saying, “There may be something in it.”

Maibaum was stirred instantly by Fleming’s suave leading man, a chap named James Bond. He liked the possibility of action-adventure films set in exotic locales, but recognized that the outlandish elements of Fleming’s plots would only work if the scripts were laced with humor. In his hands, the Bond movies had the knack of making sly fun of themselves without resorting to buffoonery. As the filming of 1962’s Dr. No, commenced, author Fleming was surprised that the filmmakers were not going for an elegant and brainy hero, on the order of David Niven. Instead they chose a brawny former Edinburgh milkman who’d also been a minor league soccer player, an underwear model, and a Disney musical star (of the forgettable Darby O’Gill and the Little People). The rest, of course, is movie history, with Maibaum writing 13 screenplays for a whole parade of Bonds.

Maibaum had started out as a serious playwright with social issues on his mind. While he was still a student at the University of Iowa, his anti-lynching drama made it to Broadway. He also wrote the very first anti-Nazi play, Birthright. Then his stage comedy about the insurance industry, Sweet Mystery of Life, was picked up by Hollywood and turned into a Busby Berkeley musical, Gold Diggers of 1937. After that he found himself in Hollywood to stay.

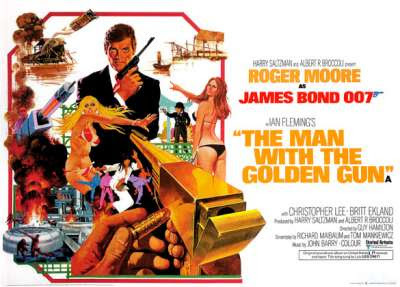

Unlike so many east coast intellectuals, Maibaum never believed he was lowering himself by writing for the movies. He was an affable man, tolerant of the beliefs of others, by no means a rabble-rouser. (Which meant he escaped from the Hollywood “red scare” of the 1950s totally unscathed.) Instead he was known for his gentleness, his wit, and his intellectual curiosity. My friend Matt remembers the day when his younger brother discovered in an encyclopedia the oddly shaped ring of islands known as Phuket, Thailand. Looking up from his Underwood cast iron typewriter, Maibaum was instantly fascinated by his son’s find. This was, he proclaimed, exactly where an exotic hit man would choose to live. That’s how Phuket became a location in one of the James Bond films starring Roger Moore, 1974’s The Man with the Golden Gun.

Richard Maibaum died at a ripe old age in 1991. His last Bond film was 1989’s License to Kill. What he would have thought of the latest and most serious Bond, Daniel Craig, is not for me to say.

Published on February 03, 2017 10:42

January 31, 2017

La La Land, Revisited: We’ll Always Have Paris

So a La La Land, the most L.A.-centric of movies, has copped the lion’s share of this year’s Oscar nominations. I’m charmed that this new musical film lovingly presents a romantic, technicolor vision of the city of my birth. And yet, within the film’s (rather slight) story, it’s Paris that remains the place of glamour and opportunity. Spoiler alert : It’s Mia’s trip to Paris that turns her world around and makes her dreams come true.

I’m sure this irony wasn’t lost on filmmaker Damien Chazelle, who borrowed heavily from old French musicals when writing and directing La La Land. The movie’s already-famous opening, in which freeway commuters leap out of their vehicles and proceed to sing and dance, is a direct steal from Jacques Demy’s The Young Girls of Rochefort. This 1967 flick begins when the members of a traveling carnival troupe spring from their caravan of trucks to stage an impromptu musical number in the middle of a country road. Demy’s French-language film also features both Gene Kelly and George Chakiris of West Side Storyfame, thus reminding us of the long artistic connection between France and Hollywood. Kelly was, of course, the star of the 1951 Best Picture musical, An American in Paris, which ends in a fantasy ballet sequence that’s either breathtaking or brain-numbing, depending on your point of view. Some of the spirit of that ballet has also found its way into the conclusion of La La Land.

Despite its Paris setting, An American in Paris was made almost entirely on the MGM lot in Culver City, California. For Casablanca, filmed as World War II raged, a romantic Paris flashback was shot on the designated “French Street” at Warner Bros.’ Burbank studio. The original 1954 Sabrina also fakes its Paris locales. But eventually, as Hollywood production became more international, actual Parisian locations were put to good use in romances (1957’s Love in the Afternoon and Funny Face, along with 1958’s Gigi) and thrillers (1963’s Charade). The trend certainly continues. Woody Allen set aside his love affair with New York City long enough to shoot the delightful Midnight in Paris (2011) and the second film of Richard Linklater’s Sunrisetrilogy—2004’s Before Sunset---also makes use of genuine Parisian byways.

French filmmakers adore the City of Lights too. Paris plays itself in nouvelle vague films like Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, Louis Malle’s Zazie dans le Metro, and Agnes Varda’s Cleo from 5 to 7. It’s worth mentioning that when Jacques Demy (Varda’s husband) came to the U.S. to follow up on the international success of his The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, he chose to make his English-language debut, Model Shop (1969) on the streets of Los Angeles. As he later told the L.A. Times, “I came here for a vacation, not to make a movie. But I fell in love with LA. . . . I learned the city by driving—from one end of Sunset to the other, down Western all the way to Long Beach. LA has the perfect proportions for film. It fits the frame perfectly.”

I’ll close with a very charming, very French film that became an international hit (and prompted a craze for taking photo-booth snapshots and sending garden gnomes on trips ‘round the world). Amélie emerged in 2001, and quickly won the love of romantics everywhere. Now it’s a musical headed for Broadway. That’s, I guess, because Paris puts a song in our hearts.

On the other hand, look at 2011’s Best Picture winner, The Artist. It’s a French-made silent film about the glories of early Hollywood, shot entirely in L.A.

Published on January 31, 2017 09:13

January 27, 2017

Less and (Mary Tyler) Moore: Thoughts About Women in the Arts

The sad news of the death of Mary Tyler Moore has put me in a nostalgic mood. I remember how much I loved laughing at her – and with her – on both The Dick Van Dyke Show and The Mary Tyler Moore Show. It’s worth pointing out, of course, that she was an actress and not simply a charmer. Her chilly performance in Ordinary People was definitely worthy of its Oscar nomination. But when I think about her, my mind goes back to a charity basketball game I attended, one in which the Harlem Globetrotters were challenged by Hollywood celebrities. The players were all male (I think I recall Ryan O’Neal and Henry Mancini on the court), but there was a cluster of female cheerleaders trying hard to rouse the crowd. The one person who truly stands out in my recollection is Mary Tyler Moore, who seemed to be bubbling over with delight at the opportunity to wave her pompoms for a good cause.

Along with Moore’s death, this past week has brought an Oscar nomination roster that points up that—as writers and directors—women are still at a distinct disadvantage in Hollywood. And I’ve just finished reading the biography of a once-famous 19th century American writer whose life story points up the complex and self-contradictory role of women in the arts. Anne Boyd Rioux’s fascinating Constance Fenimore Woolson: Portrait of a Lady Novelist deals with a figure previously unknown to me. In her own day, though, she was hugely popular, with critics as well as the reading public. Such literary giants as Henry James were her admirers and close friends.

Woolson struggled, though, with the fact that in the post-Civil War era there was still a stigma attached to being a literary female. (See the Gilbert and Sullivan lyric, from The Mikado, about “that singular anomaly, the lady novelist” as one of the social species “who never would be missed.”) A demure Victorian lady, Woolson was bold in writing about the passions of others but kept her own life strictly within bounds. After a romantic disappointment in her youth, she embarked on a writing career with a firm determination to be independent and self-supporting. The corollary, for Woolson, was that she permitted herself no room to consider marriage and children. At the same time, she shied away from the public acclaim enjoyed by male authors in her day, feeling the need to deprecate her own talents in their presence.

Woolson died tragically, a probable suicide, in 1894. The news spread quickly throughout the English-speaking world, but there was little sympathy for her in an era when (in the words of biographer Rioux) “an aura of tragic sensitivity had not yet formed around the image of the suicidal artist.” In later years, the suicides of authors Virginia Woolf and Sylvia Plath were the stuff of movies. (See The Hours, for which Nicole Kidman won an Oscar, and Sylvia.) Woolson, though, not proto-feminist enough to be re-discovered, is mostly forgotten.

How does all this fit with the perky Mary Tyler Moore? Her first TV roles, like that of a sexy receptionist on Richard Diamond, Private Detective, focused on her body, not her brains. But on The Mary Tyler Moore Show (1970-1977), playing an associate producer at a Minneapolis TV station, she demonstrated it was possible to be a smart, talented female who succeeded in the workplace without sacrificing her girlish appeal. In an era when—in reaction to the old-fashioned world of Constance Fenimore Woolson—feminists were often seen as strident, Moore’s TV image pointed us toward a middle path.

Published on January 27, 2017 10:51

January 24, 2017

George Lucas: The Unlikely Star of “Star Wars”

A few weeks back, amid all the doom-and-gloom stories about American politics, world affairs, and bizarre weather events, the Los Angeles Times featured a rare cheerful headline. the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art was heading for L.A.’s Exposition Park. The choice of Los Angeles over San Francisco as the site of filmmaker George Lucas’s self-financed billion-dollar museum was by no means a sure thing. Though civic boosters like L.A. mayor Eric Garcetti had pushed for this, various commentators opposed it. More important, Lucas has never had much affection for L,A. as a cultural milieu. Yes, he’s been extremely loyal to his film school alma mater, the University of Southern California, which has benefitted hugely from his largesse. But as soon as his career permitted, he abandoned Hollywood for the San Francisco Bay and his super-private Skywalker Ranch.

My friend and colleague, Brian Jay Jones, is the author of the fascinating new unauthorized biography, George Lucas: A Life. When we discussed the newly-announced plans for the museum, Brian admitted to being surprised. In his words, “I thought Lucas would surely want it in his backyard where he could piddle around with everything.” As I’d learned from reading Brian’s book, George Lucas is both a mild-mannered guy and the ultimate control freak.

Lucas started out in workaday Modesto, California as a mediocre student passionate about pop music and fast cars. American Graffiti, his first big hit, is a fair picture of his teen years. Early on, his imagination was shaped by comic books, TV, futuristic heroes like Flash Gordon, and an opening-day visit to Disneyland with his family. This trip took place in July 1955, when Lucas was an impressionable eleven-year-old. The now-long-gone Rocket to the Moon ride was one of his special favorites. It’s certainly fitting that, decades later, Lucas was able to participate in the launching of a more updated Tomorrowland adventure: Star Tours.

It was after he entered film school at USC that Lucas truly came into his own. At first he cultivated his skills as an editor. Later, after moving into directing, he continued to rely on his technical abilities, sometimes to the detriment of story and performance. Like my former boss Roger Corman (who was also particularly devoted to technical matters) Lucas never developed a gift for working with actors. But there’s no question that he knew what he wanted.

I learned from Brian Jones’ biography that Lucas has never been happy writing screenplays. Yes, he’s cranked out a number of Star Wars scripts, but (especially as the Star Wars universe has continued to expand) he’s astonishingly willing to move into production without a finished screenplay in hand. As a longtime screenwriting instructor in UCLA Extension’s world-renowned Writers’ Program, I cringed in discovering how much Lucas exalts post-production over the rigors of the writing process: “The editing is how I create the first draft.”

Of course Brian’s book is full of fascinating tidbits, like how C-3PO got his voice. (He was originally supposed to sound like a Bronx used-car dealer, not an English butler.) Brian also spends considerable time showcasing Lucas’s determination to upgrade every element of the original film to take advantage of technological breakthroughs since 1977. It’s certainly understandable that purists are not happy with alterations to a film they know and love. This is especially true when Lucas’s tweaks seem to change beloved characters like Han Solo (who in Lucas’s revised version shot the bounty hunter Greedo only in self-defense). The last line of Brian’s author bio makes his own feelings crystal-clear: “He continues to believe that Han shot first.”

Published on January 24, 2017 12:27

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers