Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 87

July 11, 2017

Comic-Con(fidential)

With Spider-Man: Homecoming toppling all box office expectations in its debut weekend, superheroes with comic-book roots are once again showing their muscle. And, no surprise, the mega-big San Diego Comic-Con is just around the corner. As are a whole heap of smaller comic-cons in venues literally all over the world. (I happen to know that Ghent, Belgium, just finished up a two-day gathering of comic-book fans last weekend.)

With Spider-Man: Homecoming toppling all box office expectations in its debut weekend, superheroes with comic-book roots are once again showing their muscle. And, no surprise, the mega-big San Diego Comic-Con is just around the corner. As are a whole heap of smaller comic-cons in venues literally all over the world. (I happen to know that Ghent, Belgium, just finished up a two-day gathering of comic-book fans last weekend.)I continue to marvel (sorry about that!) at the popularity of comic books and the movies they engender. Though I enjoy all the excitement, I admit that comic books have never played a big part in my own life. Blame it on my parents, who disdained the form, though they were avid readers of the Sunday “funnies” in our local newspaper. These days, though, I’m beginning to appreciate comic book aesthetics, which have given life to such remarkably vivid memoirs as Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home. The graphic novel, after all, is a sophisticated interweaving of deft verbal language and the powerful visual style unique to the comic book.

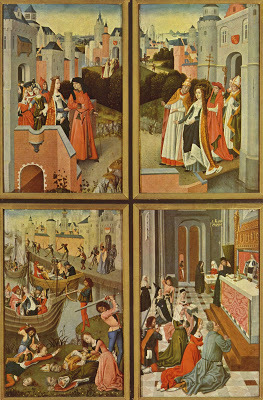

I was thinking a lot about comic books while touring Belgium recently. As a first-time tourist, I visited many a cathedral and studied the religious paintings of many Old Flemish masters. How did medieval church fathers draw in parishioners who couldn’t read? They spelled out the tenets of the faith through images that glowed down from stained-glass windows and through paintings with a strong dramatic presence. I’ve seen early artwork in which – sometimes all on one canvas – a specific believer is born, grows to adulthood, embraces Christianity, fends off minions of Satan, and suffers a spectacular martyrdom. Check out (below) the four-panel Bruges altarpiece showing the legend of St. Ursula. (It’s not especially gruesome, but it conveys the idea.) Aside from the religious angle, doesn’t it look like a comic book?

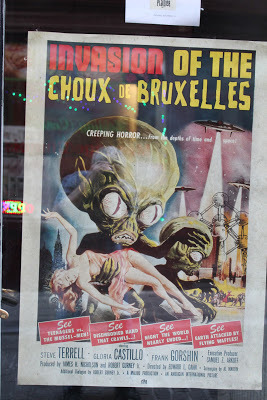

I keep bringing up Belgium because this is a nation with a long history of medieval artistry but also one that has embraced superheroes and comic books with passion. Brussels (once the home of Tintin’s creator, Hervé) can even boast a twenty-five year old museum called the Belgian Comic Strip Center. And I saw that ad for Ghent’s Comic-Con when I poked my head inside the city’s Superhero Café, where Marvel and DC memorabilia abounds.

I was recently asked whom I’d invite to my own dream Comic-Con. I know a five-year-old boy who’d invite Spider-Man in a heartbeat. Sorry, but for me superheroes don’t make the grade. Thinking back to my own misspent youth, sneaking comic books at my best friend’s house, I realize that Katy Keene (she of the fan-designed dresses) wouldn’t be on my invite list today. Maybe Betty and Veronica: they both had spunk, unlike the doltish Archie. Later, perhaps, a few select members of the Peanuts gang: in my teen years we all cherished copies of Happiness is a Warm Puppy. But—absolutely—I’d want to have Michael Doonesbury and his Walden U classmates. These young people, with their angst and their social awareness, formed a real backdrop for my college years. And in Joanie Caucus I found a role-model for a mature female who didn’t stop evolving when she became a wife and mother. For a poignant reminder of what childhood is like, I’d want the sorely missed Calvin and Hobbes. And in tribute to my late parents, perhaps some lovable Shmoos from Al Capp’s Li’l Abner. Before Capp turned reactionary in the Sixties, his was a bold voice, skewering fat-cat pomposity. Seems to me that today we need that more than ever.

The Belgian passion for B-movies and bad jokes shows up in the poster above, which I saw in the window of a Manga store just off the Grand-Place. Cribbing an image from Roger Corman’s Attack of the Crab Monsters logo, it promises the Invasion of the Brussels Sprouts.

Published on July 11, 2017 14:42

July 7, 2017

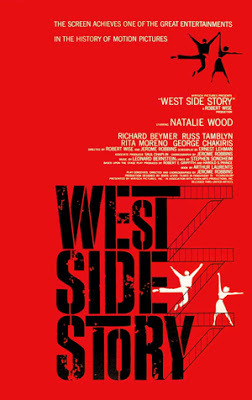

Soaring Aloft with West Side Story

I can’t believe it’s been 55 years since I walked into Grauman’s Chinese Theatre to see the brand-new West Side Story. Everyone at my high school was excited about what this stage musical would look like on the big screen. As SoCal kids, we were hardly familiar with the original Broadway production, which had opened (to only modest acclaim) back in 1957 when we were still in elementary school. Maybe we’d heard some of the show’s score on our parents’ cast albums. But West Side Story didn’t become an international phenomenon until the movie was released in October 1961. Suddenly everyone wanted to be a Jet or a Shark, and to dance down New York City sidewalks with fingers snapping to a Leonard Bernstein beat.

And the appeal wasn’t solely to American audiences. A high school classmate, newly arrived from the Republic of South Africa, told me that every boy in his social set yearned to buy a tight purple shirt, in emulation of the Sharks’ handsome Bernardo. That classmate, of course, was white. It was still the era of apartheid, and South African blacks weren’t permitted to see the film, for fear it would give them dangerous ideas.

I relived my high school experience on a seat-back screen while flying from Amsterdam to L.A. I’m grateful indeed to those airline programmers who realize that not every passenger wants to watch the latest shoot-‘em-up. As a matter of fact, one thing that today makes West Side Story seem quaint is that, in a story about rival gangs duking it out in a New York slum, only one gun is drawn. Death in this film is horrific, not matter-of-fact. Would that today’s real-life gang members could be so cowed by the sudden loss of a few young men.

Of course, the creators of the original West Side Story, who included playwright Arthur Laurents along with Bernstein and a very young Stephen Sondheim, knew that their stage production would in no way accurately capture what was happening on the streets of Manhattan. Their aim was to translate Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet into a modern context, turning the Capulets into recent arrivals from Puerto Rico and the Montagues into white kids whose own immigrant roots go slightly further back. It was a dynamic concept, one lifted into the realm of the extraordinary by Bernstein’s pulsing music and the choreography of the great Jerome Robbins, who also directed.

When the time came to make the movie, the directorial reins were handed to Robert Wise, a Hollywood veteran who’d edited Citizen Kane before moving into directing. Wise had depicted New York’s mean streets in films like Odds Against Tomorrow (1959), but he had no experience with musicals. That’s why Jerome Robbins was invited aboard as co-director and choreographer. It was hardly a match made in Heaven. Robbins, a perfectionist who could be brutal on those around him, was fired midway through, though he was still eventually honored with a director credit.

Of course one big difference between stage and screen musicals is that stage performers must be able to do their own singing. Hollywood was comfortable hiring attractive stars and then dubbing in someone else’s voice. Poor Natalie Wood desperately wanted to sing Maria’s arias. She strenuously rehearsed, because no one had the heart to tell her that Marni Nixon had already been hired to vocalize her songs. Today perhaps we’re more resistant to the idea of ghost voices (as well as using Caucasians in dark makeup to play Latinos.)

But fifty years later, one thing hasn’t changed. I still shed tears at the ending.

Published on July 07, 2017 09:47

July 4, 2017

Cosplay Superheroes -- Fantasy Goes Dutch

We’re now nearing the end of an annual L.A. event called the Anime Expo. It’s a huge celebration of Japanese pop culture that unfurls in Downtown L.A.’s convention center for four days, ending on the Fourth of July. Because what could be more American than a festival featuring cartoons, videogaming, karaoke, and a chance to dress up as your favorite comicbook superhero? Angelenos, whose enthusiasm has made this the largest anime convention in North America, love the opportunity to show off strange outfits and revel in outlandish kitsch.

Come to think of it, this passion for comic book culture is not solely American. When I recently got off the train in the Netherlands’ sedate capital, The Hague, I was prepared for sleek modern buildings, quaint town squares, a royal palace, and tony embassies. The Hague is the home of the great Mauritshuis Museum (home of Vermeer’s “Girl with Pearl Earring”) as well as the World Court, so I anticipated a certain amount of gravitas. What I didn’t expect was a hotel lobby full of zombies, seven-foot warriors wearing costumes made of cardboard, and French maids with pink hair. It was, I learned, a gathering of mostly Dutch anime enthusiasts (some of them pretty long in the tooth), who gather each year for a cosplay weekend at some large convention hall. There were screenings, merchandise sales, and special appearances to entice them, but they spend most of their days hanging out and snapping selfies with their new friends. Some of them looked scary, but it was soon crystal-clear they were a harmless bunch. Mostly, perhaps, they came off as children who’d never quite grown up.

What is there about the urge for fantasy that makes the Dutch (normally considered a sensible group) dismount from their bicycles and indulge in fancy-dress? Some of those costumes can’t be cheap, and there’s also the cost of travel and lodgings to consider. My time in various Dutch cities also reminded me of the new passion for tattooing. As popular in Amsterdam as it is in L.A (or maybe even more so), tattooing seems to be one more way of seeking personal uniqueness by way of outrageous—even sometimes deliberately obnoxious--display.

Perhaps there’s something about modern life that is short on color and glamour. In many ways, despite some grim things in the news, we’re statistically safer now than in previous eras (I can’t imagine the Dutch rushing to single themselves out during the dark days of World War II). And so we crave fantasy that gives us a heightened sense of the drama of our own lives. That’s partly why we cling to the magical world of Harry Potter, as well as to the candy-colored manga at which Japanese animators excel.

I just finished spending the morning before the 4thof July exploring a fantasy escape-room along with members of my family. I’m not sure how long this escape-room fad has been around, but it’s fascinating to learn that it began in Russia, where escaping the dismal present is a long tradition. I hear that some of these elaborately-themed escape-rooms suggest a world that is somber and even bloody. Happily, my group entered the Wizards Workshop, which puts a definitely PG spin on the genre. To leave, we had to solve eccentric puzzles galore, but there weren’t a lot of grim surprises. But goodness! the world looked bright once we were finally back outside of the wizard’s lair. We’d had the fun of feeling ourselves inside a movie, just like Harry Potter and his crew. Next time I’m wearing a cape.

I just finished spending the morning before the 4thof July exploring a fantasy escape-room along with members of my family. I’m not sure how long this escape-room fad has been around, but it’s fascinating to learn that it began in Russia, where escaping the dismal present is a long tradition. I hear that some of these elaborately-themed escape-rooms suggest a world that is somber and even bloody. Happily, my group entered the Wizards Workshop, which puts a definitely PG spin on the genre. To leave, we had to solve eccentric puzzles galore, but there weren’t a lot of grim surprises. But goodness! the world looked bright once we were finally back outside of the wizard’s lair. We’d had the fun of feeling ourselves inside a movie, just like Harry Potter and his crew. Next time I’m wearing a cape.

Published on July 04, 2017 10:05

June 30, 2017

Keeping an Eye on Movies from Around the Globe

The hot topic in Hollywood right now is the diverse new class of movie folk (774 of them) who’ve been invited to join the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. In the wake of the #OscarsSoWhite controversy, most of the attention has gone to the fact that many on the invite list are people of color. (Last year’s Oscar-winning Moonlight has itself spawned a large group of invitees, including director Barry Jenkins, actresses Naomie Harris and Janelle Monáe, and cinematographer James Laxton. ) But Justin Chang’s article in yesterday’s Los Angeles Times points out another aspect of the Academy’s new thinking: it’s reaching out to respected filmmakers from all over the globe. Chang happily enumerates offbeat but worthy new academy members from Brazil, Greece, Japan, Hong Kong, Portugal, Iran, and the Philippines, along with a gaggle of Bollywood stars.

The hot topic in Hollywood right now is the diverse new class of movie folk (774 of them) who’ve been invited to join the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. In the wake of the #OscarsSoWhite controversy, most of the attention has gone to the fact that many on the invite list are people of color. (Last year’s Oscar-winning Moonlight has itself spawned a large group of invitees, including director Barry Jenkins, actresses Naomie Harris and Janelle Monáe, and cinematographer James Laxton. ) But Justin Chang’s article in yesterday’s Los Angeles Times points out another aspect of the Academy’s new thinking: it’s reaching out to respected filmmakers from all over the globe. Chang happily enumerates offbeat but worthy new academy members from Brazil, Greece, Japan, Hong Kong, Portugal, Iran, and the Philippines, along with a gaggle of Bollywood stars. I can’t pretend I know every name on Chang’s list of moviemakers from foreign lands. (Shame on me, of course, but there are so many movies and so little time.) Still, I’m thrilled at this recognition of the international appeal of cinema. My recent travels have reminded me that a love of movies extends far beyond American shores.

Film history snobs will be quick to point out that moviemaking was international from the start. In many ways it began in France (via Georges Méliès and the Lumière brothers), and some of its most prized stylistic ideas came from Russia and Germany. But there’s no question that Hollywood-style movies became pre-eminent, and the stars of Hollywood’s Golden Age are still cherished the world over. Case in point: last week when I walked into a trendy Amsterdam coffee bar, I was instantly captivated by its décor. On its walls were dozens of close-up movie stills of such celebrities as Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, and Paul Newman, each of them posed clutching a cup of coffee.

Many cities around the world have film centers where fans can gather to watch and discuss movies, as well as enjoy movie-themed exhibits. In Paris, the Cinémathèque Française is legendary, dating back to the saving of silent films during World War II. New York can boast its Museum of the Moving Image, now housed in a former building of the historic Astoria Studios in Queens. Shockingly, Los Angeles has never had a full-fledged film museum, though the American Cinematheque screens films both in Hollywood (at the Egyptian Theatre) and in Santa Monica (at an historic neighborhood movie-house called the Aero). Happily, a long-awaited museum sponsored by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is now under construction next door to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

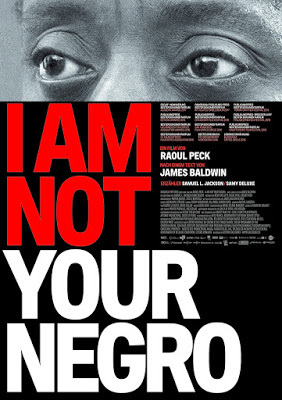

In Amsterdam, I was privileged to visit EYE Film Institute Netherlands, housed in a spectacular building across the Ij River from the city’s central train station. (Its name comes from a pun on the Dutch pronunciation of the river it overlooks, and you take a free ferry ride to get there.) On a recent Saturday evening, I arrived too late to enjoy a vast display of memorabilia relating to the career of Martin Scorsese. But I could choose between four films to watch in comfortable screening rooms. In this particular timeslot, only two were in English: an ethereal Japanese travelogue on Mt. Fuji and Raoul Peck’s hard-hitting I Am Not Your Negro, based on the writings of James Baldwin. I watched the latter, surrounded by respectful Dutch viewers. And then there was time for a glass of wine and a tasty meal in a busy café overlooking the lights of Amsterdam. The Dutch know how to do movies right.

Published on June 30, 2017 12:34

June 27, 2017

Frank Capra: A Not Always Wonderful Life

Director Frank Capra’s famous 1971 memoir, The Name Above the Title, contains a phrase that is often quoted in Hollywood: “Only the morally courageous are worthy of speaking to their fellow men in the dark.” These were the words that Jane Fonda had inscribed on a plaque as a 1981 Christmas gift for her producing partner, Bruce Gilbert, around the time they made On Golden Pond. Like many other Hollywood denizens, Fonda found inspiration in the courage that had allowed Capra to make such hard-hitting social comedies as Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and Mr. Deeds Goes to Town.

Alas, as Joseph McBride points out in his powerful 1992 biography, Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success, Capra was not always the gutsy maverick his own memoir makes him out to be. Capra, a Sicilian immigrant desperate for fame and social acceptance, was a shrewd man who knew how to be affable. Actors loved him for his relaxed and supportive behavior on the set. But—determined to live by an auteurist credo of “one man, one movie”—he proved to be ungenerous to collaborators, never fully acknowledging the role played by such talented colleagues as screenwriter Robert Riskin and cinematographer Joseph Walker. Moreover, especially later in his career, he had debilitating periods of self-doubt.

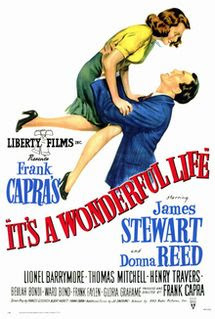

During World War II the patriotic Capra enlisted in the military and proved essential to the U.S. cause as the head of the unit producing the “Why We Fight” morale films. He ended the war as a full colonel, valued by General George Marshall to the extent that he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. But the post-war period brought him little personal satisfaction. An attempt to form an independent film company was a flop, and he seemed to lose the buoyant spirit that had marked his earlier movies. McBride sees the suicidal George Bailey of It’s a Wonderful Life as a near-portrait of Capra himself, without the Christmas-card ending.

McBride, a longtime scholar and journalist (as well as a Roger Corman alum who once dreamed up the plot for Rock ‘n’ Roll High School) had the advantage of working directly with Capra on the American Film Institute’s Life Achievement Award tribute evening. When McBride moved on to this biography, he gained access to the Capra archive at Wesleyan University, as well as to documents in government files. He also spoke to many of Hollywood’s leading lights, who shared a wide range of opinions about the beloved but complicated director. A tireless researcher, McBride did not fail to pinpoint contradictions between Capra’s charming but self-serving memoir and the truth to be found in the paper trail. No wonder the book took him eight years to write.

Before reading this biography, I had not realized the extent to which Capra’s life was shaped by politics. The myth fostered by Capra himself was that he was a champion of the little guy within American life. And so his best films make him seem. He also, by playing a leadership role in the formation of what would become the Directors Guild, appeared to be siding with labor against the studio system. But he was also a lifelong Republican who consistently voted against FDR and at one time admired Mussolini. In the difficult years of the House Un-American Activities Committee, he was so desperate to avoid accusations that he became virulently anti-Communist, even to the point of naming names to the FBI. Said one former colleague, “The blacklist killed him—that panic. In effect, he was a victim of the backlist. [But] he had the soul of an informer.”

Published on June 27, 2017 09:30

June 23, 2017

“The Player”: Pitching “The Graduate, Part II”

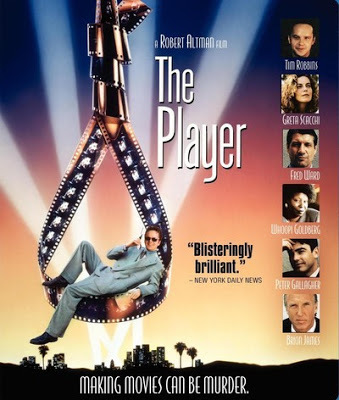

Few would consider Robert Altman a Hollywood director. Though he enjoyed hits like MASH (1970), the box-office failure of Altman’s ambitious McCabe and Mrs. Miller made studios reluctant to send production money his way. Still, no one has been better than Altman at skewering the way Hollywood goes about its business. I just re-watched his 1992 film, The Player, and marveled at how well it understands moviemaking, Hollywood-style.

Not that my own years in the film industry resembled what happens on the movie lot depicted in The Player. Working for B-movie maven Roger Corman on the low-budget end of Hollywood, I hardly spent my days in a capacious office suite, nor enjoyed pricey lunches among the beautiful people. (In fact, my deal required me to eat at my desk, while going through piles of script submissions.) Still, I experienced enough of Hollywood to recognize the film’s acid-dipped portrayal of insecure people jostling one another for position. I understood Hollywood’s obsession with star-power and with cranking out formulaic movies chockful of the list of traits described in The Player: “Suspense, laughter, violence. Hope, heart, nudity, sex. Happy endings. Mainly happy endings.” I grasped why nearly every pitch heard by studio types within the film has a role guaranteed to be tailor-made for Bruce Willis or Julia Roberts.

And, of course, I love The Player because it features my friend Adam Simon. Fans of the movie will remember that The Player begins with an eight-minute tracking shot that roams the studio lot repesented by Hollywood Center Studios, the former site of Francis Ford Coppola’s Zoetrope. As the roving camera fleetingly captures development execs driving through the gate in sleek cars, listening to pitches, and giving Japanese investors insider tours, a down-at-the-heels screenwriter-type named Adam Simon is desperately trying to accost anyone who might be interested in his latest project. He’s shrugged off by one and all, and a dapper Griffin Mills (star Tim Robbins) demands to know who let him onto the lot. As the film’s story begins to unfold, poor Adam (his actual name is used on screen) is being hustled away, still trying to convince someone—anyone—of his value as a storyteller. It’s a better picture of the writer’s status in Hollywood than any other I’ve seen.

(Adam Simon is still around and still writing. I knew him in my Concorde years as the writer-director of several horror films, including the innovative Brain Dead and Roger Corman’s biggest video hit, Carnosaur. His horror documentary, The American Nightmare, is well worth a look. He got the gig in The Player partly because he’s a longtime friend and colleague of Tim Robbins, with whom he helped found the Actors’ Gang, a local theatre troupe. Adam can’t spell, but he’s a very good guy.)

Adam Simon is not the only sighting in The Player of the writer-as-victim. The film is, among other things, a thriller, and a writer named David Kahane comes to a bad end in a way that sends Griffin Mills’ life completely out of control. But there are lots of other writer-characters as well, most of them busy pitching their hearts out to suits who are barely being polite. That long tracking-shot at the start features a pitch by none other than Buck Henry, who’s enthusiastically pushing a follow-up to his own screenplay for The Graduate: “Ben and Elaine are married still. . . . . Mrs. Robinson, her aging mother, lives with them. She’s had a stroke. And they’ve got a daughter in college—Julia Roberts, maybe. It’ll be dark and weird and funny—with a stroke.”

Published on June 23, 2017 09:30

June 20, 2017

One Summer at the Movies: Bill Bryson Looks Back

What’s the big deal about 1927? Bill Bryson, my favorite pop historian, devotes an entire book to the events between May and September of that year. The book is called One Summer: America, 1927. Bryson makes a great case for the fact that the personalities who came to the fore during that six month period—aviator Charles Lindbergh, baseball great Babe Ruth, President Calvin Coolidge, anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti—helped make the United States into the 20th century powerhouse it would soon become.

Naturally, the subject of movies crops up. Movies were evolving back then from a cheap attraction for the lower classes into a full-fledged art form, and their use in capturing reality can’t be overstated. When Lindbergh made the first successful aerial crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, newsreel cameras were in Paris to greet him. Manhattan’s huge new Roxy Theatre showed an exclusive Movietone newsreel of Lindbergh taking off from Roosevelt Field, in which sound was an integral component. As Bryson describes it, “loudspeakers were set up in the theater wings, and a technician with good timing played a separate sound track so that the engine’s initial sputters and final triumphant roar matched the image on the screen.” The combination of sound and visuals brought six thousand patrons to their feet at every screening.

Feeding on the excitement generated by this new era of aviation, Walt Disney released a new Mickey Mouse cartoon called “Plane Crazy.” And after his flight the triumphant but very private Lindbergh was offered $500,000 and a percentage of the profits to star in a cinematic version of his life. According to Bryson, he could have earned as much as $1 million if he’d agreed to be filmed while searching for and finding the girl of his dreams, culminating in a Hollywood-style wedding.

Meanwhile taciturn President Calvin Coolidge was discovering how much he liked appearing on film. Having shown up at a South Dakota hunting lodge for a long summer vacation, he insisted that his whole entourage reload their luggage into cars and drive 200 yards down the road so they could re-enact the presidential arrival for the newsreel cameras.

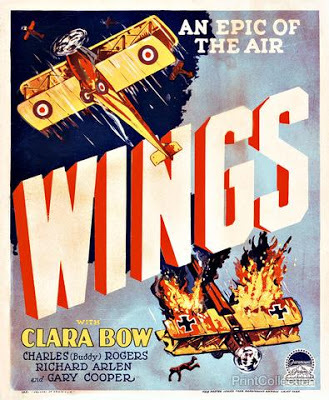

In Los Angeles, home of movie magic, the big sign in the hills still read Hollywoodland, advertising a local housing tract. But studios were churning out 800 feature films a year. Movies were now the country’s fourth largest industry, but few individual pictures made much profit. Early film moguls looked for answers in new stars (like the sexy “it” girl Clara Bow), new cinematic expertise (the aerial stunts in Wings were spectacular by any standard), and new technologies (this was of course the year of The Jazz Singerand the advent of the talking picture). Meanwhile, exhibitors tried to elevate the moviegoing experience by building extravagant movie palaces. Bryson mentions the kitschy Orientalism of Grauman’s Chinese but especially the bejeweled Roxy on 50th Street and 7th Avenue in New York City. It seated 6,200 moviegoers, but could also accommodate elaborate stage performances. Fourteen Steinway pianos were at the ready; the Roxy also boasted air-conditioning and push-button ice-water dispensers. A New Yorker cartoon of the era showed an awed child asking her mother, “Mama, does God live here?”

Bryson laments, as so many cineastes do, the fact that talkies swept in as silent film was reaching its aesthetic peak. But he makes a fascinating statement about the impact of sound in movies. With a few exceptions, Hollywood’s stars spoke with Americanvoices. “With American speech came American thoughts, American attitudes, American humor . . . America was officially taking over the world.”

Published on June 20, 2017 09:30

June 16, 2017

Best in Show: A Mockumentary that’s Going to the Dogs

A few weeks back, while huffing and puffing on the elliptical trainer at my gym, I chanced to flip TV channels and came upon the Beverly Hills Dog Show. History was being made: for the very first time the dog show’s Best in Show competition was being broadcast on television. Frankly, it’s hard for me to imagine who would care. Then again, I don’t understand the rationale behind dog shows in the first place.

Yes, the dogs are – one and all – quite beautiful. Best in Show means that the winners in various specialized categories (the work dogs, the terriers, the toys, and so on) are competing against one another, with one to be named the overall winner. The Best in Show competition in Beverly Hills pitted a whippet against a corgi, a bichon frise, and several others. As is apparently typical of dog shows, none of them is expected to do anything spectacular (like, say, rescuing Timmy from a burning building). Each trots around a circle at his or her master’s side, and then stands at attention, waiting to be admired for being a credit to his or her breed. Judges study the dogs from all angles, examining their teeth and gently lifting their tails. Frankly, it reminded me of a scene from Twelve Years a Slave, except that these dogs were competing for trophies, not being auctioned off to the highest bidder.

The other distinctive thing about a dog show is that the dogs are far more graceful and aristocratic than the human beings. Each owner accompanies his or her prize-winner around the ring, sprinting lumpily at the canine’s side. They’re an unlikely lot: the men dressed in sober business suits, the women in ill-fitting tailored attire (with skirt inevitably too short, too tight) and flat-heeled shoes. And their seriousness of purpose can’t be missed.

No wonder Christopher Guest felt that dog shows were ripe to be satirized. Guest (also known, as the 5th Baron Hadon-Guest) first fell into the mockumentary business when he appeared as rocker Nigel Tufnel – the one whose amp goes to eleven -- in Rob Reiner’s 1984 classic, This is Spinal Tap. Following up this comic salute to “one of England’s loudest bands,” Guest began directing his own semi-improvised mockumentaries, featuring a troupe that generally includes Eugene Levy, Catherine O’Hara, Fred Willard, Michael McKean, and Parker Posey. I’ve never quite gotten over their first effort, 1996’s Waiting for Guffman, about a small-town musical revue whose castmates dream of showbiz success. (Guest himself is a hoot as Corky St. Clair, imported from Broadway to lead the locals to glory.)

But Best in Show (2000) may be the merry band’s most popular effort. I think it’s because audiences love dog movies, and also because in this film the dogs have so much more dignity than their human handlers. Take Sherri Ann Cabot (Jennifer Coolidge), a trophy wife whose standard poodle Rhapsody in White is the stoic victim of Cabot’s penchant for sartorial makeovers. Or Gerry and Cookie Fleck (he has, quite literally, two left feet, while she seems to have past history with every man she runs across): they like to serenade their Norwich Terrier, Winky, with their own semi-musical dog barks. Or the Swans (Parker Posey, Michael Hitchcock), a yuppie couple whose own social and sexual neuroses seem to have caught up with their Weimaraner. Only Guest’s own character, a backwoods type named Harlan Pepper, actually seems at one with his bloodhound. Who wins? That’s for me to know. . . .

But I’d say it’s the audience. (Then again, I find beauty pageants hilarious too.)

Published on June 16, 2017 09:30

June 13, 2017

“Seinfeldia” Gives Us the Yadayada . . . Not That There’s Anything Wrong With That

Though the show Seinfeld left primetime in 1998, after a stellar nine-season run, it still has plenty of fans. That can be proven by its success in syndication, by the existence of such social media sites as @Seinfeldtoday, and by the incorporation into our language of references to Festivus and the Soup Nazi. A Brooklyn Cyclones baseball game held in 2014 at a Coney Island stadium was a good-natured gathering of Seinfeld enthusiasts who showed off their affection for their favorite show by donning Jerry Seinfeld-style puffy shirts, imitating Elaine’s herky-jerky dance moves, passing out Vandelay Industries business cards in imitation of sadsack George Costanza, and hawking “master of my domain” sweatshirts.

The source of all this Seinfeld trivia is a bestselling 2016 book by Jennifer Keishin Armstrong, now newly out in paperback. It’s called Seinfeldia: How a Show About Nothing Changed Everything, and it digs deep into the Seinfeld archives, exploring Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld’s original impetus for the show, how the characters evolved, how the writing staff functioned, and how the public came to adopt “a show about nothing” as their own. The origin stories of some of the most famous episodes are here (“The Junior Mint”!), and we’re introduced to the actual people who gave their personalities and in some cases their names to members of the cast. I particularly like the way a poster advertising one of the show’s fake art-films, Rochelle Rochelle, showed up recently on a defunct New York marquee, totally surprising the SoCal woman who’d posed for it twenty years earlier. Rochelle Rochelle, billed as “a young girl’s strange, erotic journey from Milan to Minsk,” was only one of the movies the Seinfeld characters favored. Others, including Prognosis Negative, Chunnel, and Sack Lunch, have since been given their own photoshopped posters by fans of the show, with Hollywood celebrities in the leading roles.

What apparently made Seinfeld a standout in its day was its attention to the minutiae of daily life, as filtered through the perception of characters who are lovable but not exactly likable. Larry David insisted from the start that sentimentality would never be part of the mix. His credo (which later got printed on jackets for cast and crew): “No hugging, no learning.” When Seinfeldbegan, both David and Jerry were standup comics who were TV production novices. But once the show caught on, their very flip, very meta style began to have imitators. Soon the aesthetic of Seinfeld was starting to dominate TV sitcoms: cutting became quicker, laugh-tracks were eliminated, “single-camera” on-location shooting began to be favored over three-camera shoots in front of a studio audience. There were other kinds of influences at work too. One newspaper editorial credited Seinfeld with turning around the reputation of New York City in the 1990s. Audiences took away from Seinfeldthe fact that the city was a funny, quirky place to live (this despite the fact that almost all the filming was done in L.A.)

Author Jennifer Armstrong’s research for Seinfeldia took her to some interesting places. She learned a lot in discussing the show with the woman charged with translating it into German. So much does Seinfelddepend on the quirks of the American idiom that a good translation is nearly impossible. Take for instance the episode when Jerry tries to remember the name of a girlfriend. She’s told him it rhymes with a female body part. Just imagine being the translator who needs to come up with a Germanic name that fits a very private part of the German anatomy. (In English, the name turns out to be Dolores.)

Published on June 13, 2017 09:30

June 9, 2017

Harold and Lillian: In Love With Movies, and With Each Other

Though Harold and Lillian is rightly billed as “a Hollywood love story,” it’s taken two years for this film to arrive at SoCal theatres. This amiable documentary, made in 2015 by the Oscar nominated director of The Man on Lincoln’s Nose, chronicles a lifelong love affair between a former GI named Harold Michelson and the best friend of his little sister. Because Lilian Farber was poor and an orphan, Harold’s family did not welcome her into their ranks. So the two eloped to post-war Hollywood, where Harold was beginning to put his artistic skills and his keen eye to work, drafting storyboards for some of the world’s best filmmakers.

Most of us outside of filmmaking circles don’t know much about storyboards. They are a series of cartoon-like drawings, intended to graphically sketch out for the film crew exactly what scenes will be shot, and from what perspective. Harold, who had been an aerial navigator and bombardier over Germany during the second World War, was especially adept at combining his drawing skills with a sophisticated comprehension of distances and angles. The biographer James Curtis, who recently published a book on the legendary contributions of William Cameron Menzies to the field, agrees with me that some directors—especially those with no camera experience—rely heavily on sketch artists to map out their visuals prior to shooting. In those instances, the storyboard artist makes a huge (though generally unsung) contribution to the way a film unfolds. In other cases, a director with a sophisticated grasp of what a camera can do makes artistic choices that the storyboard artist simply renders on paper.

Daniel Raim, writer-director of Harold and Lillian, seems understandably eager to give Harold Michelson full credit for creating the look of films as famous as Hitchcock’s The Birds and Mike Nichols’ The Graduate. The film’s interview subjects, who range from Francis Ford Coppola to Mel Brooks to Danny DeVito (he also functions as executive producer), loudly sing Harold’s praises. And I can’t deny that he worked on a number of major Hollywood productions, including Ben-Hur, The Apartment, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, and Catch-22. Later in his career he moved up to the post of art director, nabbing Oscar nominations for his work on Terms of Endearment and Star Trek: The Motion Picture. Clearly he was a very talented man, though I doubt that he singlehandedly gave the imperious Hitchcock his famous sense of visual style. And as the author of an upcoming book on The Graduate, due out in November 2017 from Algonquin, I can’t buy the idea that filming Benjamin Braddock through Mrs. Robinson’s arched leg was entirely Harold’s brainstorm.

While Harold was putting in long hours at various Hollywood studios, the feisty Lillian struggled to raise three sons, one of whom had serious psychological difficulties. Along the way, she also fell into her own life’s work, when she became a volunteer at the film research library on the Paramount lot. Eventually she was to buy that library, struggling to find a home for it at such varied studios as Coppola’s Zoetrope and Dreamworks. Alas, such libraries are becoming rare at today’s movie studios, but her books and files were invaluble in checking out visuals and historic details for such films as Reds and Fiddler on the Roof. For the latter, she needed to verify what sort of undergarments would be worn by Jewish girls in an eastern European shtetl. Always an intrepid researcher, she went to the legendary Cantor’s Deli on Fairfax to track down some elderly Jewish ladies who supplied her with a pattern from their girlhood.

Published on June 09, 2017 09:30

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers