Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 89

May 5, 2017

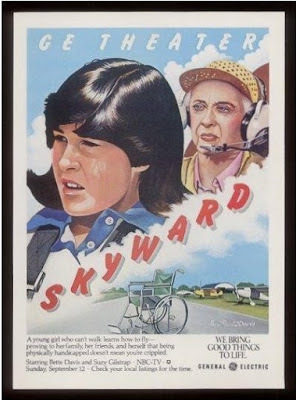

A Post-Feud Bette Davis Goes Skyward

The enthusiasm with which TV audiences and critics have greeted Feud, and its unfurling saga about the making of Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, proves that megawatt stars like Bette Davis and Joan Crawford never fall completely out of fashion. The opportunity to see Susan Sarandon and Jessica Lange go toe to toe as legends of the past is something to be cherished. All this excitement reminded me of a little-known episode in Davis’s great career. In 1980, some eighteen years after the filming of Baby Jane, Davis signed on to star in one of fledgling director Ron Howard’s first movies for television.

Howard, who had made his directorial debut with a 1977 Roger Corman car-chase flick, Grand Theft Auto, tried to further his career with a series of modest movies for television. Cotton Candy (1978) and Through the Magic Pyramid (eventually released in 1981 but made several years earlier) did him no favors. But in 1980, having just made an emotional departure from the cast of Happy Days, he embarked on a gutsy project that was to star a true Hollywood dragon lady. The film was called Skyward.

Skyward was made for NBC under the terms of Howard’s new three-year contract. It was produced in conjunction with Howard’s former Happy Days co-star Anson Williams, who was also looking for new career options. While making a personal appearance, Williams had once chatted with a glum young man in a wheelchair, who complained, “I’m tired of looking up.” From this, Williams devised a story idea about a disabled boy and an old black man who teaches him to fly an airplane. Writer Nancy Sackett transformed this barebones premise into a two-hour teleplay about a wheelchair-bound girl, overprotected by her well-meaning parents, who finds a new lease on life when she learns to pilot a bi-plane. Skyward was a landmark production because it was the first television drama in which a handicapped character was portrayed by an actor with a genuine disability. For the role of sixteen-year-old Julie Ward, Howard chose Suzy Gilstrap, a plucky teenager whose spine had been crushed by a falling tree during a school outing. Howard showed courage in hiring as his leading lady a paraplegic who was also a complete acting novice. He was equally brave when it came to casting Bette Davis as the veteran stunt pilot who shows Julie how to take to the sky.

Howard has often recounted what it was like, at age twenty-six, to direct the seventy-two-year-old Davis. Then near the end of her long and lively career, Davis accepted this part because she had never before played an aviator. She loved the script, but was suspicious of her director’s youth and inexperience. At first, she was icily polite, refusing to call him anything but “Mr. Howard,” because “I don’t know whether I like you yet.”

On the set, she loudly questioned his ideas—until he sweet-talked her into trying one scene his way, and she found herself pleased with the results. From that point forward, life improved immensely. At the end of the shooting day, she patted him on the rump and said, “See you tomorrow, Ron.” What Howard quickly discovered was that actors—even legendary ones—will respond well when they are treated as trusted collaborators. Skyward was praised by critics for broaching big issues while avoiding cheap sentimentality, and roundly applauded by groups that advocate for the disabled. The film’s official premiere took place in Washington, D.C., in conjunction with a yearlong federal focus on disability issues. In Los Angeles, Mayor Tom Bradley proclaimed “Skyward Day.”

On the subject of Happy Days, a not-so-happy farewell to Erin Moran, whose career soared when she was cast as Ron Howard’s kid sister on that long-running series.

Published on May 05, 2017 12:35

May 2, 2017

Hemingway and Dos Passos: Frenemies to the End

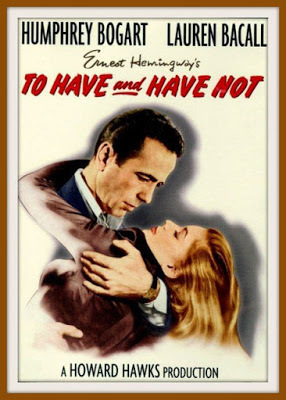

Almost 50 years after his death in 1961, Ernest Hemingway remains an American icon. Schoolchildren continue to know (or at least I hope they do) such masterworks as In Our Timeand For Whom the Bell Tolls. Cineastes revere films based on Hemingway novels, like To Have and Have Not, which gained fame as the first and sexiest on-screen pairing of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. In various picturesque parts of the globe there are Hemingway statues as well as watering holes named after his favorite drinking spot, Harry’s Bar in Venice. I once made a pilgrimage to a Madrid restaurant called Botín because Hemingway’s Jake Barnes had feasted on suckling pig there, washed down with a nice rioja, in The Sun Also Rises.

Not only have many of Hemingway’s works been filmed (as far back as 1932, Gary Cooper and Helen Hayes starred in a screen version of A Farewell to Arms) but he himself has appeared as a character in numerous Hollywood movies and TV series. Some were intended as seriously biographical, but he has also shown up in several fanciful projects. A Hemingway character was featured in TV’s Young Indiana Jones Chronicles. does not actually materialize in an offbeat 1993 indie called Wrestling Ernest Hemingway, but I still treasure Corey Stoll’s robust portrayal of the author in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris.

When Hemingway was just starting out, the talk of the literary world was John Dos Passos, a Harvard graduate with an exotic upbringing, a talent for art, and strong leftwing leanings. The two met in Paris in the 1920s, and quickly bonded. One thing that drew them together, aside from their literary interests, was that both had experienced the bloodshed of World War I while serving as volunteer ambulance drivers on the battlefields of Europe. The twists and turns of their relationship are chronicled by my friend and colleague, James McGrath Morris, in a short but fascinating book called The Ambulance Drivers: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and a Friendship Made and Lost in War. The sad truth of the matter: Hemingway was not easy on his friends. At the beginning, the chum and drinking companion he called “Dos” performed an invaluable service by bringing Hemingway’s work to the attention of New York publishers. But later, as the esoteric works of Dos Passos (who experimented with using cinematic techniques like montage on the printed page) earned more respect than money, Hemingway resented needing to make loans to keep Dos and his wife afloat. Eventually, as he came to do with all his (former) friends, he was cruelly lampooning Dos Passos in print

Jamie Morris is at his most captivating when he compares Hemingway and Dos Passos in terms of their feelings about war. Dos Passos, says Jamie, “had come away from the experience with the belief that war was a macabre and purposeless dance of death.” By contrast, Hemingway looked to war as a place for a man to prove himself, as well as a prime opportunity for romance. Hemingway’s own wartime experience of near-death followed by a passionate love affair is the stuff that movies are made of. Hollywood heroes, like Hemingway himself, tend to find that the closeness to death make them feel more alive, and the vicarious excitement makes moviegoers feel alive too.

There are also a lot of famous Hollywood movies that chronicle wartime friendships: see, for instance, the Vietnam era films The Deer Hunter and Platoon. From the example of these movies and others, friendship in time of war doesn’t fare so well in the long term.

Published on May 02, 2017 11:57

April 28, 2017

I Remember Jonathan Demme

I never knew Jonathan Demme well. But he was part of my early days in the film industry, and so I add my voice to those who are paying tribute to this talented, eclectic filmmaker, who died of cancer Wednesday at age 73.

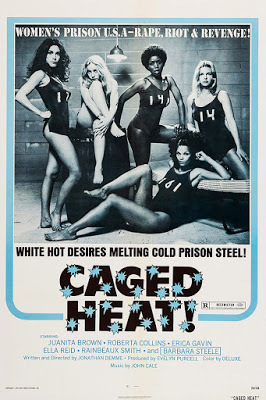

Back in 1974, in the early days of Roger Corman’s New World Pictures, I was a jill-of-all-trades, working on scripts and publicity releases, while dipping my toes into the mysterious business of film production. Jonathan had attracted Roger’s attention by crafting the script for a motorcycle movie in the style of Akira Kurosawa’s classic Rashomon. By the time I joined the New World staff, he had his first shot as a director. Though he filmed in East L.A. instead of in Roger’s go-to exotic location, Manila, Jonathan’s Caged Heat was hailed by some perceptive critics as both a tribute to and a brilliant satire of the women-in-prison fare for which New World was becoming famous.

I participated in Caged Heat only on the sense of contributing to its marketing campaign. But Jonathan soon became a familiar sight around our Sunset Strip office suite, wandering the grimy halls with his very tall, very Australian then-wife Evelyn Purcell in tow. You couldn’t miss Jonathan: he of the shaggy hair, friendly grin, and brown-and-white saddle oxfords. But I wouldn’t have guessed that he’d be a future Oscar winner, for directing the 1991 thriller, The Silence of the Lambs.

My one close encounter with Jonathan came when, on the strength of Caged Heat, he was offered by Roger the chance to write and direct a co-production with Twentieth-Century Fox. This was the era of tough-guy movies with outrageous rural heroes. Billy Jack had done well at the box office. So had a vigilante film about a Southern sheriff, Walking Tall, and a rambunctious NASCAR flick, Dirty Mary Crazy Larry. Roger’s genius was that he always knew how to take what was working elsewhere and repackage it with a little more sex, a little more violence. Jonathan was sent off to do some thinking. Then he met with Roger and the New World story department (Frances Doel and me) over lunch at a local eatery. It was one of the very rare lunches I ever had on Roger’s dime. Jonathan wowed us by holding up a chart in which he compared his new film concept, point by point, to those three low-budget hits. He decreed that his hero, too, needed a sidekick, an unusual weapon, and a trademark mode of transportation. So he proposed that in his Fightin’ Mad, his leading man would ride an old Indian motorcycle, wield a crossbow, and hang out with his toddler son. Most of that ended up changing, but Fighting Mad (without the apostrophe) was eventually produced, with Peter Fonda in the lead.

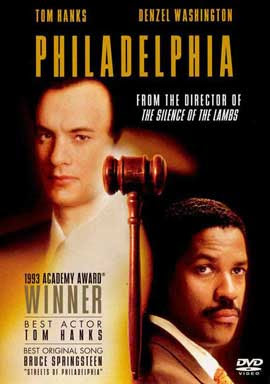

In his later years, Jonathan paid tribute to his former mentor by casting Roger in virtually every film he made. Sometimes Roger’s roles were miniscule, like that of a wedding guest in Rachel Getting Married. In Silence of the Lambs, Roger has little personal screen time, but—because he’s the movie’s FBI chief—his photo appears on the wall in many scenes. His most sizable role came as a wily businessman in Philadelphia, the powerful 1993 AIDS drama for which Tom Hanks won his first Oscar.

Demme’s affection for his old boss never waned. It was he who called it “the thrill of a lifetime” to present Roger with an honorary Oscar in 1991. Hard to believe that Demme is gone now, while Roger Corman, at 91, keeps on rollin’ along.

Published on April 28, 2017 14:57

April 25, 2017

A Little Danish in La La Land

In the City of the Angels (now newly known as City of Stars), April 25, 2017 has been officially proclaimed “La La Land Day.” To celebrate this momentous event, dancers wearing bright primary colors will be dangled from bungee cords down the side of the L.A. City Hall tower. That seems a fitting salute to this award-winning film, on what is sure to be another day of sun.

L.A. is clearly besotted by a movie that pays tribute to its own wacked-out glory. I know people who’ve already bought their tickets to a big event scheduled in late May for the Hollywood Bowl: a La La Land Concert, with the movie accompanied by a hundred-piece live orchestra and (presumably) by anyone who cares to sing along.

Personally, these events aren’t for me, even though I thrill to the excitement of musical theatre. I grew up with a strong appreciation for musicals performed live, on stage, and it’s rare for me to see a movie musical that outshines its stage version. I’ll make an exception for West Side Story (great film!), but I firmly believe that a true stage metamusical, like A Chorus Line, shouldn’t even try to work as cinema.

Which makes it curious that today’s Broadway producers keep looking to Hollywood for new material. Check out how many of the current long-running Broadway musicals originated as films: Aladdin, Kinky Boots, School of Rock, Waitress, The Lion King. And this season’s new hopefuls include musicalized stage versions of Anastasia, Amélie, and Groundhog Day.

I’m particularly obsessed with stage musicals right now because a young writer who’s near and dear to me, Jeff Bienstock, is just back from Denmark, where his original musical (with composer Andrea Daly) had its world premiere. Their Legendale moves in and out of the videogame universe, and its cast includes a Wild Warrior, a Cow Maiden, a creepy Alchemist, and several Zombie Robots, along with more everyday folk. The head of Denmark’s Fredericia Theater, Søren Møller, snapped up Legendale when he saw a workshop production in New York City. As he told the opening night Danish crowd, the show made him feel he was watching beloved films of his childhood: ET, Back to the Future, Raiders of the Lost Ark . He emphasized that he fell in love with the Legendale script partly because of its cinematic possibilities.

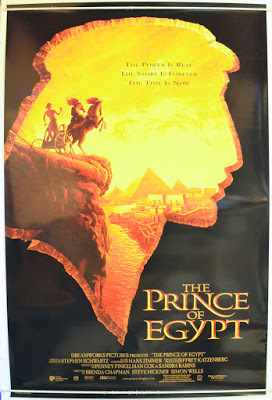

The rear of the Fredericia Theater stage is spanned by huge curved panels encrusted with thousands of LED lights. Through the magic of technology, Legendale’s audiences could see behind the actors such glowingly realistic effects as a gushing waterfall, a fiery explosion, soaring birds, and trees swaying gently in the wind. In Søren’s words, Legendale is “changing the perspective of what theatre can be.” Other musicals included on the Fredericia Theater’s roster of late are direct stage adaptations of big Hollywood animated musicals: Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame and DreamWorks’ The Prince of Egypt. These too take advantage of the Danish theater’s spectacular electronic wizardry. So little Denmark, where per capita funding for cultural activities far exceeds anything we’ve ever had (or are likely to have) in the U.S., is expanding the horizons of theatre production by way of the inspiration of the cinema.

For the youngest generation of playgoers it may occasionally be hard to tell the difference. Somewhere on Facebook’s Fredericia Theater site, I spotted mention of an overheard comment in praise of Legendale – “En pige på omkring syv år sagde: ‘Det var en god film’” Which of course is Danish for “A seven-year-old girl said, ‘That was a good movie.’”

Published on April 25, 2017 13:33

April 21, 2017

Death of a Jock: Aaron Hernandez and the Movies

The big news coming out of the sports world as I write this is the suicide of Aaron Hernandez, who starred as a tight end for the Super Bowl-winning New England Patriots. At the time of his death, Hernandez was in prison serving a life sentence for fatally shooting a friend. Less than a week after he was acquitted of a double-homicide in Boston, he was found in his cell, dangling from a noose made out of bedsheets.

Hernandez’s brief life (he died at 27) seems to have been continuously marked by violence. Back in 2007, when he was a seventeen-year-old college football player at Florida State in Gainesville, he refused to pay a bar tab, then punched a barroom employee so hard that he shattered the man’s eardrum. Later that same year he was implicated but not charged in a Gainesville incident in which five shots were fired into a car at a stoplight, wounding two. Pundits say these were classic cases in which a prized jock eluded punishment because of his value to his team and his sport. Star athletes are like stars of stage and screen: their glamour allows them to pretty much get away with murder. (See the strange and disturbing case of O.J. Simpson, who was of course a celebrity in both respects, and whose acquittal on murder charges is very much part of the history of the City of Stars.)

Aaron Hernandez is hardly the first star athlete to combine physical power with a propensity for violence off the field. Some jocks, or so it seems, are fueled by rage that bubbles to the surface without warning. What’s striking is that, given how many movies focus on the wide world of sports, how few of them confront the anger that’s at the center of many athletes’ lives. Instead, sports movies tend toward fun and games, or toward a hagiographic approach in which the athlete at the film’s center seems a candidate for sainthood. Take baseball: such movies as Pride of the Yankees (about Lou Gehrig), The Jackie Robinson Story, Field of Dreams, and 42 tend to idolize baseball players. The characters in Bull Durham are less saintly, but fit into the category of charming rogues. For me the football-related movies that spring to mind also focus on heroics. See, for instance, 1940’s Knute Rockne, All American. Much more recently there’s Brian’s Song, the 1971 TV movie that became a 2001 feature film: in both the focus of this true story is on the evolving friendship of a black and white teammates who start as rivals and end as close friends, who close ranks before Brian Piccolo dies of cancer. And football becomes an ennobling experience in such high school films as Remember the Titans and The Blind Side.

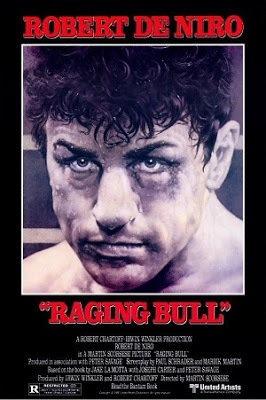

I’m hard-pressed to think of a football film in which the game’s raw cruelty is central to the story. Nor can I recall a football flick in which a character’s full-on aggression is not limited to the playing field. Are there any sports movies that dare to explore flawed men who can’t control their powerful and reckless anger? I’d suggest looking at films about boxing. The classic example, of course, is Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull, a gripping biopic about the self-destructive Jake LaMotta. In the more recent The Fighter, it’s the brother (played by Christian Bale) of the main character, real-life boxer Micky Ward, who best exemplifies the self-defeating anger that can ruin a boxer’s life.

Will the Aaron Hernandezes of the sporting world inspire any movies? Maybe these stories are just too sad to tell.

Published on April 21, 2017 10:26

April 18, 2017

The Witches of Salem: Arthur Miller and Beyond

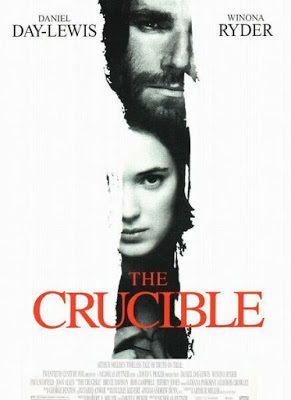

This 1996 film was based on the Miller play.

This 1996 film was based on the Miller play. Playwright Arthur Miller, I have learned, was not the last word on the Salem witch trials of 1692. Miller’s The Crucible is a powerful drama, the winner of Broadway’s 1953 Tony Award for best new play. In it Miller adapts some of the sordid doings of the Massachusetts Puritans while also making a covert statement about his own era, one in which McCarthyism was rampant and the lives of many good men and women were being destroyed by false accusations. Miller’s characters were actual historical figures—John Proctor, Reverend Parris, Giles Corey, Deputy-Governor Danforth, Tituba—but he did some creative reshaping of personalities and motives. In raising one character’s age and adding the aftermath of a spicy adulterous relationship to the mix, he sharpened the reasons why a restless young woman might lead others to cry out against their neighbors, ultimately sending them to their deaths on the gallows.

Baseless accusations and over-eager justice seem to be a part of every age, which may be why The Crucible has had a long life in community theatres and high school drama departments. I have personally been part of the cast in two local productions, both times playing a little girl caught up in the madness. It was my familiarity with the play that made me so eager to read The Witches: Salem 1692, the latest tome by Pulitzer Prize-winning historian and biographer Stacy Schiff. Though the full historical record remains sketchy, Stacy (whom I know as a fellow member of Biographers International Organization) has worked hard to detail the hundreds of arrests and the twenty public executions that the witch trials produced before those in power slowly acknowledged that “spectral evidence” was not exactly a reliable proof of guilt. She’s very good at taking on the historical perspective and delineating all the reasons (low social status, deviation from orthodox thinking, being on the wrong side of the political fence) why some folks turned out to be more vulnerable than others.

One of the most striking things about the witch trials was that they were dominated by the testimony of very young women and girls. In Puritan society, such girls would be faced with a life of hard work, drab clothing, and obedience to patriarchal strictures. Stacy sees these girls (especially girls who had lost parents to disease, death in childbirth, or Indian attacks) as desperate to add drama and color to their mundane existence. As she puts it, “History is not rich in unruly young women; with the exception of Joan of Arc and a few underage sovereigns, it would be difficult to name another historical moment so dominated by teenage virgins, traditionally a vulnerable, mute, and disenfranchised cohort.”

In writing about witchcraft, as imagined by the Puritans and those who came before them, Stacy makes occasional reference to the witch at the center of one of America’s favorite stories, The Wizard of Oz. The Wicked Witch of the West too was taken down by a little girl, though of course we are all squarely on Dorothy’s side. Stacy’s book made me think about some less-upbeat movies in which young girls with hidden motives take on their elders. In 1961’s The Children’s Hour, an angry schoolgirl destroys two teachers (Audrey Hepburn and Shirley MacLaine) by suggesting they are lesbian lovers. And 1956’s The Bad Seed stars blonde and pigtailed Patty McCormack as an adorable child who’ll do anything—and oppose anyone—to get what she wants. Maybe witches exist in the eye of the beholder?

More about witchcraft in movies six months from now, when Halloween creeps closer.

Published on April 18, 2017 11:32

April 14, 2017

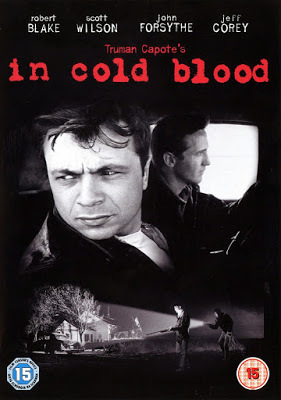

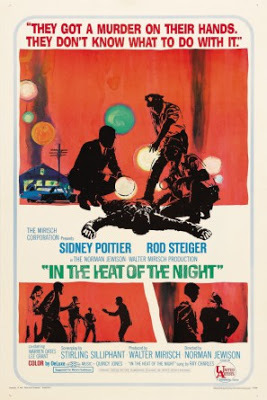

Scott Wilson Finds a Career In the Heat of the Night

Scott Wilson, as Dick Hickock, is on the right

Scott Wilson, as Dick Hickock, is on the rightThe other night, in the lobby of the Chinese Theatre, I was pleased to run into one of my favorite character actors, Scott Wilson. He was there as an honored guest of the TCM Classic Film Festival, which was screening In the Heat of the Night for its gala opening. About ten years ago, while researching the great movie year 1967, I had sat down in Scott’s comfy living room for what turned out to be a three-hour chat about his career. It started with a featured role in In the Heat of the Night, followed by a star-making turn as a real-life killer in one of 1967’s most powerful crime dramas, In Cold Blood. (One of his most memorable recent roles was as a victim – not a perp – in 2003’s Monster, where he ran afoul of Charlize Theron’s deadly Aileen Wuornos.) Though the biggest box-office hit that came out of 1967 was The Graduate, and critics applauded the bravura audacity of Bonnie and Clyde, neither of those films was named Best Picture at the 1968 Oscar ceremony. That honor went to In the Heat of the Night, a tight little whodunit that fit the mood of the country in an era when civil rights were at the top of everyone’s mind.

The Atlanta-born Scott Wilson made his film debut as In The Heat of the Night’s Harvey Oberst, a small-town Southern punk. He’s first seen by Haskell Wexler’s dramatically hand-held camera desperately running away from the town of Sparta, Mississippi. When he’s finally caught just before the state line by Sheriff Gillespie (played with Oscar-winning flair by Rod Steiger), he discovers he’s the prime suspect in a murder case. Gillespie is only too happy to pin the rap on him. But Sidney Poitier, as a Philadelphia homicide expert who finds himself stuck in this backwater Southern town, quickly assesses the situation and announces that Harvey is innocent of the charge. He may have lifted the dead man’s wallet but he didn’t kill him, because the angle of the fatal blow indicates that it was caused by a right-handed assailant. And Harvey’s a lefty.

Scott Wilson’s character, then, becomes the first in the film to acknowledge that a black man (not to mention a Yankee) is a great deal smarter and more capable than any of the locals. Through various plot twists, he eventually becomes an ally. In fact, Harvey’s evolution from hostility to appreciation for Poitier’s Virgil Tibbs foreshadows that of Sheriff Gillespie, who gradually moves from disdain to sincere gratitude for what Tibbs has contributed to the life of his town.

If Harvey Oberst has reason to appreciate Virgil Tibbs, Scott Wilson has all the more reason to appreciate the helping hand given him by Sidney Poitier. During filming, Poitier even went home one night and reworked an already strong scene between the two of them for maximum effect, then made sure director Norman Jewison was giving the young Scott some good close-ups. When Scott interviewed for the role of Dick Hickok in In Cold Blood, Poitier was one of those who approached director Richard Brooks on his behalf. (Jewison and film scorer Quincy Jones spoke up for him too.) Beyond that, Poitier took it upon himself to give the fledgling actor a pep talk, praising his talent and predicting a bright future. The result: “After he left I was like Godzilla, and I walked into that meeting with Brooks feeling very confident, having no self-doubt.” Soon thereafter, the part was his. Just one more way that Sidney Poitier made a difference in Hollywood’s film industry.

My heartfelt thanks to Scott Wilson for his talent and his gifts as a raconteur. And to his wife Heavenly for her long-ago tea and cookies.

Published on April 14, 2017 11:48

April 11, 2017

Cruising the Red Carpet in the Heat of the Night at TCM Film Festival

No, I didn’t arrive by limo. Downhome gal that I am, I took the Metro from Santa Monica to DTLA (that’s the new hip name for Downtown Los Angeles) to Hollywood and Highland, where sits the Chinese Theatre in all its glory. (Today it’s actually the TCL Chinese Theatre, not Grauman’s, and it’s owned by actual Chinese.) I could have sidestepped the red carpet and entered the theatre directly, but an intrepid blogger named Raquel Stecher, whose long-running vintage film site is called Out of the Past, wanted to meet me. Naturally, I obliged. Anything for the press!

Meanwhile a handful of excited volunteers in basic black were lined up, ready to greet arriving celebrities. Those elderly folk who arrived in my presence were not people I recognized, but they seemed delighted by all the attention. Later, after I’d filed into the splendidly exotic Chinese Theatre (whose lobby is filled with costumes of stars like Grace Kelly and Marilyn Monroe), the truly big guns showed up. On this festival premiere night (co-sponsored by the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures), they included the team behind the featured film of the evening, 1967’s In the Heat of the Night. After we’d all sat for a long time, nibbling free popcorn and watching an endless loop of festival promos, the real entertainment began. First came a heartfelt video tribute to longtime TCM resident host Robert Osborne, who passed away one month ago. Next, Osborne sidekick Ben Mankiewicz, grandson of the man who wrote the screenplay for Citizen Kane, sat down for a chat with In the Heat of the Night’s producer, Walter Mirisch, its director, Norman Jewison, and featured actress Lee Grant. All are upwards of 90, though Grant, in particular, looks surprisingly fit. When Mankiewicz welcomed the three to the stage, Jewison quipped, “I’m just glad to be alive.”

In the audience but not taking part in the discussion was the one and only Sidney Poitier, who elicited a long ovation from the crowd. Though Poitier didn’t speak, he was often evoked by the others. Mirisch noted that he and Poitier—best friends through the years—have lunch together on a weekly basis. And Poitier was much involved in the shaping of this film, which began with Mirisch uncovering a story that would highlight Poitier’s talents and outlook. Many of the anecdotes that came up were familiar to me: how they avoided shooting this tense racial drama in the Deep South (where Poitier might have faced hostile locals) by finding a suitable small town in southern Illinois; how Rod Steiger (in an Oscar-winning performance as the small-town Southern sheriff) chose to define his character by the way he chewed gum; how the moment when Poitier’s character (a Philadelphia police detective) returns the slap of a bigoted Southern overlord galvanized moviegoers everywhere.

One story I hadn’t heard before came from director Jewison. The great Quincy Jones was doing the movie’s score, which featured a bluesy title ballad, its lyrics written by the always-reliable Alan and Marilyn Bergman. When Jewison suggested that the ballad be sung over the opening credits, Jones promised to try to enlist his good buddy Ray Charles. Jewison jumped at the idea, but was stunned when he discovered that Charles insisted on seeing the movie first. Charles, of course, was blind. But Jewison gamely talked him through a private screening. Once Charles heard the double slap and realized that a black man had just made Hollywood history by retaliating against a white bigot, he exclaimed, “Maximum green!” Jewison’s still not sure what this means, but Charles’ soulful vocals add to the film’s many pleasures.

Published on April 11, 2017 09:33

April 7, 2017

A Movie Orgy in the Friendly Skies

Flight attendants, I suspect, love movies. They appreciate the fact that on long trips their passengers are so busy staring at their seatback screens that they forget to gripe and demand attention. Having just made two very long trans-Atlantic flights, I’m grateful for having movies on demand to help me pass the time.

Gone are the days when we had no choice but to watch the sole movie (generally a middle-of-the-road family film) being screened in the cabin. Since I could generally not see or hear all that well, I tended to opt for the pleasures of a good book. Today, however, we often have dozens of choices, and can stop and start a movie whenever the spirit moves us. Another innovation: the movies available are chosen to suit a wide variety of tastes. Last November, one inventive U.S. carrier offered a sampling of election-related flicks, including Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Election, Napoleon Dynamite, and Citizen Kane. And who doesn’t love an airline that gives you the opportunity to watch Audrey Hepburn at her most enchanting in Roman Holiday?

On my long flights to and from Denmark, I found myself making up personal rules for the kind of films best suited to inflight viewing. Though I’d seen La La Land before, it was a perfect choice: straightforward, upbeat, basically simple in its concept and execution. (My fellow passengers seemed to agree.) I also enjoyed watching Disney’s Moana, a family film I probably wouldn’t pay to see in a multiplex, though I’m sure its sophisticated animation worked much better on a big screen. Among the movies in the “classics” category, I was glad to reaquaint myself with Big, the 1988 gimmick film made memorable by Tom Hanks’ charming performance as a twelve-year-old boy in an adult’s body. Last year’s Oscar-nominated Lion was simple (perhaps too simple) in its concept, so that I never had to worry about losing the thread of the story, but it struck me as tedious in its excution. (That didn’t stop me, though, from tearing up at the climactic reunion scene I knew was coming.) Perhaps my absolute favorite was an oldie: Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine in The Apartment (1960). Here’s a piquant comedy that puts its accent on characterization, not quips. It’s simple; it’s sincere; it’s a great film to encounter in the middle of the Atlantic in the middle of the night.

Here’s what doesn’t work well on a seatback screen: (1) Anything with an extremely complicated plot or a very large cast of characters. (2) Anything highly dependent on verbal wit (those little earphones don’t always do a great job of conveying all the dialogue). (3) Anything in which wide-screen cinematography is a major part of the story, especially if a good deal of the story occurs in semi-darkness. (4) Anything in which characters speak in heavy dialect. I once tried watching Mr. Turner, the Mike Leigh biopic about painter J.M.W. Turner, on an airplane. Since the cast is veddy British and the film works hard to capture Turner’s shimmering artistic style via its visuals, I soon gave up. But I’m sure I’d have an equally hard time with the South Florida patois of Moonlight.

Here’s my strangest adventure in seeing a movie on a plane. Years ago, late at night, the movie that came on was an old Astaire-Rogers musical, The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle. Light fare, right? Except that at the end of this true story of an early twentieth-century dance team, Irene learns that her beloved Vernon has just been killed in a plane crash. Ooops!

Published on April 07, 2017 12:23

April 4, 2017

Roger Corman and Harry Belafonte: Going into their Nineties with Style

On the Hollywood front, this week’s big story involves the release of Going in Style. The comedy -- an updating of a 1979 flick that featured George Burns, Art Carney, and Lee Strasberg – involves three senior citizens who scheme to rob the bank that mishandled their pensions. In the new version, the leading roles are played by movie veterans Michael Caine (age 84), Alan Arkin (83), and Morgan Freeman, who will celebrate his 80th birthday in June. Also involved is one-time bombshell Ann-Margret, who turns 76 this month. The tag line says it all: “You’re never too old to get even.”

As someone who’s getting older myself, I’m always pleased to see attention being paid to performers who are hardly spring chickens. In a society that applauds youth, it’s heartening that oldsters too sometimes get allotted juicy roles. But while saluting the still-impressive talents of octogenarians Caine, Arkin, and Freeman, I also want to recognize two nonagenarians who continue to make a difference within the entertainment industry. They are very different from one another, but both are alike in not wanting to be put out to pasture anytime soon.

My former boss, B-movie maven Roger Corman, turns 91 tomorrow, April 5. Roger is well known within the film industry for directing 50 low-budget films (including such classics as House of Usher and The Little Shop of Horrors). He is also revered for giving a leg up to some of the industry’s best and brightest, including directorial aces Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Jonathan Demme, Peter Bogdanovich, Ron Howard, and James Cameron. The honorary Oscar Roger accepted in 2009 is testament to the fact that, despite his years as an indie maverick, he’s now regarded as a Hollywood elder statesman. But this hardly means that Roger’s ready for a rocking chair. His tiny company still churns out outrageous creature-features (like 2014’s made-for-TV Sharktopus vs. Pteracuda and the upcoming Cobragator). And he’s also revisiting old glories with remakes of such one-time hits as Death Race 2000 (now Death Race 2050) and Piranha (soon to be called Piranha JPN). I’ve just read that my old Concorde-New Horizons pal Katt Shea has been hired to direct a remake of her Dance of the Damned, which will apparently be retitled Dance with a Vampyre. At this stage of his career, Roger gets few points for originality. But, hey, he’s still functioning. Happy birthday, Roger! May you live long and continue to prosper!

Then there’s my mom’s favorite heart-throb, Harry Belafonte, who entered his nineties on March 1 of this year. Back in the day, of course, Belafonte was known for his calypso crooning and for the open-necked shirts that revealed his buff physique. He did well in some acting roles (see, for instance, Odds Against Tomorrow) but spent most of his time touring with his well-polished concert act, when not actively campaigning for civil rights in the company of such leaders as Dr. Martin Luther King. Today he no longer has hair on his head, and it’s been years since I’ve heard him sing, but he continues to make waves as a dedicated champion of the oppressed in every corner of the globe. His best role, it seems, remains that of a voice for the voiceless, and it’s wonderful to think that advanced age isn’t slowing him down. In 2015 Belafonte was honored with the Academy’s Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award: it’s hard to think of anyone who has deserved it more. You’re never too old to get even? Roger Corman and Harry Belafonte prove that you’re never too old to continue doing what you love.

Published on April 04, 2017 12:44

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers