Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 85

September 15, 2017

Fantasy Goes Live (and Corporate) at Universal Studios

Universal Pictures, founded in 1912, today is America’s oldest movie studio. Long ago Universal was best known for its monster films, notably Frankenstein, Dracula, and The Mummy. Universal’s affection for horror has continued through the years: visitors to the studio backlot are shown sets and memorabilia connected with such super-scary movies as Psycho, Jaws, and Jurassic Park. There’s nothing Universal loves more than a good scare.

Universal Pictures, founded in 1912, today is America’s oldest movie studio. Long ago Universal was best known for its monster films, notably Frankenstein, Dracula, and The Mummy. Universal’s affection for horror has continued through the years: visitors to the studio backlot are shown sets and memorabilia connected with such super-scary movies as Psycho, Jaws, and Jurassic Park. There’s nothing Universal loves more than a good scare.But of course it was those studio tours that really put Universal on the map as a major SoCal attraction. They began all the way back in 1915, cost a nickel, and included a boxed chicken lunch. (Today’s prices are a whole lot higher. It costs $25 simply to park your car.) In 1964, under corporate ownership, Universal began to seriously turn itself into a theme park. It started with a narrated bus ride highlighted by glimpses of stars’ bungalows and by such “surprises” as a disintegrating bridge and a flash flood that showed off what Hollywood could do by way of movie magic. Gradually, there arose Disneylandish “lands” dedicated to the Universal hits of the moment.

There’ve been some strange bedfellows in this process. For years one of the park’s most popular rides allowed visitors to vicariously experience a bonafide Universal blockbuster, Back to the Future. Eventually, though, that magic DeLorean was sent to the junkyard. As I discovered on a recent visit to Universal Studios Hollywood, this ride’s place has now been taken by an elaborate homage to The Simpsons, the long-running cartoon show that hails not from Universal but from Fox Studios. Instead of hurtling into space in miniature DeLoreans, visitors in a Simpson-esque jalopy now try to escape Sideshow Bob’s attempts to derail the Krustyland Theme Park. It’s scary and goofy at the same time.

Like most of today’s theme-park “dark rides,” this Simpsons adventure combines physical jolts with the dramatic use of film that draws visitors into the action. In other of the park’s attractions, like the one featuring those madcap Minions, 3-D glasses enhance the effect. As your seat bounces and soars, you can be forgiven for feeling a bit queasy. But it’s doubtless both cheaper and safer to explore the possibilities of the film medium than to build an old-fashioned outdoor roller coaster. And the results, while doubtless less heart-stopping for the rider, are a great deal more imaginative.

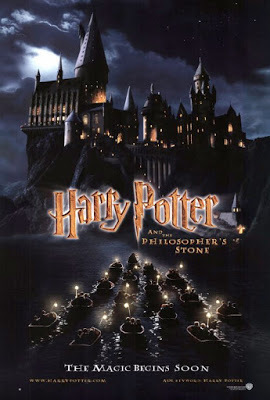

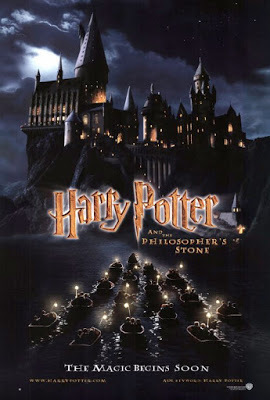

The pride of today’s Universal Studios is The Wizarding World of Harry Potter. Here once again is an elaborate “land” dedicated to a movie project made by another studio (Warner Bros.). Nonetheless, the Universal braintrust has lavished much love and care on reproducing all the familiar Potter tropes. There’s the charming town of Hogsmead, covered with snow (quite a contrast to the California summer). You can sample butter beer, have a magic wand choose you at Ollivanders, and bop to the music of a frog chorale. Above it all looms the enormous bulk of Hogwarts. Enter, and you’ll find yourself playing follow-the-leader with Harry himself as, on his broomstick, he eludes a giant dragon and plunges down toward a raging chasm. (My stomach has still not quite recovered.) In this ride above all, the possibilities of cinema as a visceral experience are fully sampled.

I was cheered by the fact that there’s live action too: clever on-site performers (like that wand-making expert), as well as cheerful employees who deftly enhance the fun. No wonder so many guests purchase interactive wands and academic robes. Much as I love movies, I adore encounters with human beings who know how to welcome me into a fantasy world.

Published on September 15, 2017 22:06

Fantasy Goes Live (and Corporate) at Universal Studios

Universal Pictures, founded in 1912, today is America’s oldest movie studio. Long ago Universal was best known for its monster films, notably Frankenstein, Dracula, and The Mummy. Universal’s affection for horror has continued through the years: visitors to the studio backlot are shown sets and memorabilia connected with such super-scary movies as Psycho, Jaws, and Jurassic Park. There’s nothing Universal loves more than a good scare.

But of course it was those studio tours that really put Universal on the map as a major SoCal attraction. They began all the way back in 1915, cost a nickel, and included a boxed chicken lunch. (Today’s prices are a whole lot higher. It costs $25 simply to park your car.) In 1964, under corporate ownership, Universal began to seriously turn itself into a theme park. It started with a narrated bus ride highlighted by glimpses of stars’ bungalows and by such “surprises” as a disintegrating bridge and a flash flood that showed off what Hollywood could do by way of movie magic. Gradually, there arose Disneylandish “lands” dedicated to the Universal hits of the moment.

There’ve been some strange bedfellows in this process. For years one of the park’s most popular rides allowed visitors to vicariously experience a bonafide Universal blockbuster, Back to the Future. Eventually, though, that magic DeLorean was sent to the junkyard. As I discovered on a recent visit to Universal Studios Hollywood, this ride’s place has now been taken by an elaborate homage to The Simpsons, the long-running cartoon show that hails not from Universal but from Fox Studios. Instead of hurtling into space in miniature DeLoreans, visitors in a Simpson-esque jalopy now try to escape Sideshow Bob’s attempts to derail the Krustyland Theme Park. It’s scary and goofy at the same time.

Like most of today’s theme-park “dark rides,” this Simpsons adventure combines physical jolts with the dramatic use of film that draws visitors into the action. In other of the park’s attractions, like the one featuring those madcap Minions, 3-D glasses enhance the effect. As your seat bounces and soars, you can be forgiven for feeling a bit queasy. But it’s doubtless both cheaper and safer to explore the possibilities of the film medium than to build an old-fashioned outdoor roller coaster. And the results, while doubtless less heart-stopping for the rider, are a great deal more imaginative.

The pride of today’s Universal Studios is The Wizarding World of Harry Potter. Here once again is an elaborate “land” dedicated to a movie project made by another studio (Warner Bros.). Nonetheless, the Universal braintrust has lavished much love and care on reproducing all the familiar Potter tropes. There’s the charming town of Hogsmead, covered with snow (quite a contrast to the California summer). You can sample butter beer, have a magic wand choose you at Ollivanders, and bop to the music of a frog chorale. Above it all looms the enormous bulk of Hogwarts. Enter, and you’ll find yourself playing follow-the-leader with Harry himself as, on his broomstick, he eludes a giant dragon and plunges down toward a raging chasm. (My stomach has still not quite recovered.) In this ride above all, the possibilities of cinema as a visceral experience are fully sampled.

I was cheered by the fact that there’s live action too: clever on-site performers (like that wand-making expert), as well as cheerful employees who deftly enhance the fun. No wonder so many guests purchase interactive wands and academic robes. Much as I love movies, I adore encounters with human beings who know how to welcome me into a fantasy world.

Published on September 15, 2017 10:00

September 12, 2017

Richard Nixon, TV Star

I admit I didn’t approach John A. Farrell’s Richard Nixon: The Life with much excitement. After personally surviving the Nixon era, I’d read some books, and watched some movies, and that seemed quite enough for me. But Jack Farrell’s new biography of the only U.S. president to resign from office turns out to be as exciting as the best-crafted thriller. It’s chockful of revelations, many of them benefitting from the recent release of scores of documents and White House tapes to scholars. And Farrell’s taut, vivid prose jolts the Nixon story to life. Here’s a pre-Watergate tidbit involving some early underhanded scrutiny of perceived enemies: “The surveillance yielded little but gossip and traces of bureaucratic jockeying. Nixon and his aides, with a revealing degree of self-consciousness, at long last packed the transcripts up and locked them in a White House safe, where their faint tick tick tick was, for a time, forgotten.” (Yes, this passage reminds me of a screenwriter’s best friend: the ticking clock.)

As a man and a president, Richard Nixon was inspired by movies, particularly Patton, which he watched over and over in times of stress. But at many key points his career was driven by the new medium of television. Farrell details how, in 1952, at the point when his place on the Eisenhower ticket was threatened by allegations of financial misconduct, Nixon turned to TV to make his case to the American people. Though the optics were crude and were improvised on the spot, it worked. He became Ike’s two-term running mate.

Television was less a friend to him, of course, in 1960, when—as the Republican candidate for president—he entered into a series of nationally televised debates with Senator John F. Kennedy. Farrell notes that since Nixon’s entry into national politics in 1950, “the percentage of American households with television sets had leaped from 11 to 88 percent. . . .The audience for the first debate was some 70 to 80 million people, in a country with 107 million adults.” In that first head-to-head, Kennedy proved handsome, articulate, confident. Nixon, done in by fatigue, a bad makeup job, and the public perception that he was ill at ease, could not hope to match the challenger’s poise.

Nixon lost the presidency in 1960, but was back on the hustings in 1968, at a time of political and social turmoil. Following the assassination of presidential candidate Robert Kennedy, Nixon’s aides strongly suggested he trade in public appearances for media events, like the “man in the arena” telecasts in which he showed off his political savvy by fielding questions from a panel of voters. As one advisor put it, “The greater the element of informality and spontaneity the better he comes across. We have to capture and capsule this spontaneity—and this means shooting RN in situations in which it’s likely to emerge, then having a chance to edit the film so that the parts shown are the parts we want shown.”

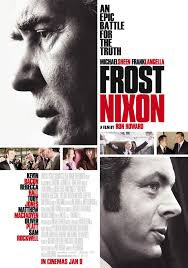

So Nixon became a president of an evolving media age. Of course, the television cameras were there as the Watergate scandal continued to electrify the public. When Nixon stepped down from the presidency on August 9, 1974, they captured his final words and his final “V for victory” salute. Three years later, beginning on March 23, 1977, they recorded his unprecedented series of interviews with British journalist David Frost. The results were so riveting that they evolved into Frost/Nixon, a 2006 British play that took Broadway by storm. In 2008, Ron Howard directed original stars Frank Langella and Michael Sheen in the Oscar-nominated movie.

Published on September 12, 2017 12:36

September 8, 2017

Chilling Out with “Wind River”

When SoCal was sweltering in the grip of the summer’s third heatwave, I decided to take myself to the movies. A perfect choice was a film set in early spring in the frozen wilds of Wyoming. True, Wind River was filmed mostly in Utah. But its sense of place is so powerful that for the length of the movie I felt a genuine chill.

“Wind River” refers to an Indian reservation, one that’s about as desolate as can be imagined. In the film’s early going, a character who makes his home near the rez explains the implications of this lonely place: “My family’s people were forced here, stuck here for a century. That snow and silence—it’s the only thing that hasn’t been taken from them.”

It’s an apt quote, because this is a film about loss. Which means it’s tremendously sad, but also exhilarating, because the characters who people Wind River are so human: angry, funny, stoic, despairing, and determined to live out their lives on the best terms they can get. They include Jeremy Renner in another of his masterful from-the-gut performances as a hunter with the Fish and Wildlife Service, Elizabeth Olsen as an unlikely FBI agent, and a clutch of remarkable Native American actors, including Graham Greene, once nominated for an Oscar for his supporting role in Dances with Wolves.

Dances with Wolves, which nabbed seven Oscars (out of 12 nominations) back in 1991, makes an interesting contrast to Wind River. When the Kevin Costner vehicle made its debut, it was hailed for its picturesque and highly sympathetic portrayal of Native American life. Unlike classic westerns in the John Wayne mold (see Stagecoach or The Searchers), it did not show Indians as heartless marauders, but rather as a sophisticated culture with a rich heritage. Of course, that was a period piece, as well as something of a romance, with the Indian characters coming off as noble savages. The Native Americans in Wind River have ordinary American names (Ben, Natalie, Martin) and wear ordinary American clothes. Old tribal rituals seem to have little appeal for them. Some of these characters have aspirations to do more with their lives than just hang on. But most seem stuck in a place that discourages dreams. There’s hopelessness and drug abuse. And young Native American women blessed with beauty and spirit are all too vulnerable to threats from both within and without. The film ends with a shocking revelation: the FBI keeps no statistics on missing Indian women, whose numbers remain unknown.

Taylor Sheridan, a native Texan, is best known as an actor for his role in TV’s Sons of Anarchy,. Recently he has written three important westerns: Sicario, Hell or High Water (Oscar-nominated for its screenplay), and Wind River. The latter, only his second film as a director, takes him far from his roots in the American Southwest, but allows him to air his strong concerns about Native American life in today’s United States. Wind River also shows us what’s best about an actor’s approach to screenwriting and directing: the characters are complex, and the script avoids on-the-nose dialogue at all cost. At this year’s Cannes Film Festival, Wind River won plaudits and a Best Director award in the Un Certain Regard competition. Here’s part of Sheridan’s Cannes speech: “There is nothing I can do to change the issues afflicting Indian country, but what we can do as artists -- and must do -- is scream about them with fists clenched. What we can do is make sure these issues aren't ignored.”

Published on September 08, 2017 10:25

September 5, 2017

The Stars Shine on Sunset Boulevard

For the boys and ghouls among us, an alive-and-kicking organization called Cinespia presents classic Hollywood movies projected against a mausoleum wall on the grounds of the Hollywood Forever memorial park. It’s a weekly event staged during L.A.’s spring and summer nights. The series started up in 2002: now on Saturday evenings some 3500 patrons crowd onto the hallowed Douglas Fairbanks lawn—blankets, picnic hampers, candles, and bottles of wine in tow—to enjoy the best of Hollywood oldies.

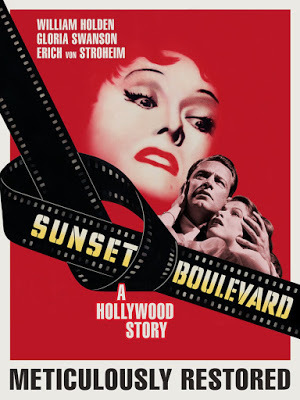

Labor Day weekend’s offering was so absolutely well suited to its locale that Cinespia sent out a special email notice: “The legendary film about the dark side of fame comes to Cinespia. A down-on-his-luck screenwriter stumbles upon a mysterious mansion on Sunset Blvd and enters a dark fairytale that could only be told in Hollywood. SUNSET BOULEVARD is brilliant, compelling and downright terrifying. [Fading star Norma Desmond] is played to perfection by Gloria Swanson in one of the most chilling performances in cinema.”

Is it fair to call Sunset Boulevard, as Cinespia suggests, “the greatest cemetery screening of them all”? This can be argued (The Night of the Living Dead, for one, is a pretty apt movie to show in a graveyard). But no one can deny that this location, right in the heart of old Hollywood, is hugely resonant when it comes to this particular movie. Here’s the Cinespia email again-- “You’ve never seen SUNSET BOULEVARD like this: next to the legendary Paramount Studios lot, where Norma Desmond plans her final comeback, by the resting place of director Cecil B. DeMille, who [inspires] her haunting close up, and the tombs of Valentino, Fairbanks and the stars of Norma’s milieu.” I wasn’t able to attend the Cinespia screening, but the hue and cry made me revisit the film on my own. It’s always surprising to recall that Billy Wilder, best known for such witty romps as The Apartment and Some Like It Hot, was the co-writer and director of Sunset Boulevard. It’s a tragic tale of desperation, delusion, and death, but it’s also at times mordantly funny, especially in its view of the life of a Hollywood screenwriter. Here’s William Holden’s Joe Gillis describing his failed career as a crafter of screenplays: "The last one I wrote was about Okies in the Dust Bowl. You'd never know, because when it reached the screen, the whole thing played on a torpedo boat." And when a fresh-faced studio reader (Nancy Olson’s Betty) says to Joe, “I’'d always heard that you had some talent, " he shoots back, “That was last year. This year I'm trying to make a living."

Joe’s sardonic words are a prime encapsulation of what Hollywood writers go through. By my own day, though, one aspect of the story had changed forever. Joe and his colleagues work (when they work at all) for the big studios. Yes, they’re at the beck and call of honchos like De Mille (who plays a featured role in the film), but such men have the ability to make things happen. Betty, a lowly reader who wants to move up in the screenwriting ranks, has a steady job and a pretty cushy office on the Paramount lot. And when an old star like Norma Desmond happens onto a set, it’s like a family reunion. Today’s Hollywood is a great deal more decentralized. The bigshot decision-makers come and go so quickly that few remember their names. When a legend is ready for her close-up, it’s hard to think of anybody who’d have the courtesy to put her in the spotlight one last time.

Published on September 05, 2017 17:55

September 1, 2017

Cryin’ in the Rain

Anyone who’s paid any attention to the news knows that Houston and other parts of Texas have been tragically inundated by the flood waters of Hurricane Harvey. Lives have been lost, and property damage is said to be in the billions. Louisiana has not escaped unscathed, and as I write this another tropical storm – Irma – is gathering off the U.S.’s eastern seaboard. Here in California, after five years of drought, we’ve all learned to pray for rain. When it came, this past winter, we rejoiced, though the rain’s impact on dry-as-dust terrain led to rapid new plant growth that has encouraged forest fires. So rain, like most things, can have both positive and negative consequences. Gene Kelly, happily in love, kicked up his heels in the middle of a downpour in the perennially charming Singin’ in the Rain. But most movies I know of use rain to send an ominous message.

There are an awful lot of movies that have the word “rain” in their titles. One of the most famous of the oldies, called simply Rain, is a 1932 dramatization of a short story by British writer Somerset Maugham. It was a 1922 play and then a silent movie before Joan Crawford took on the role of Sadie Thompson, opposite Walter Huston. He’s a stuffy missionary; she’s a classic bad girl. Stuck in steamy Pago Pago with a boatload of others, he wants to save her soul, but ends up coveting her body. Needless to say, it does not end happily. I can’t pretend to have seen anywhere near all the rain movies helpfully listed in IMDB. But here are some titles: Hard Rain (1998), Black Rain (1989), Purple Rain (1984), A Hatful of Rain (1967), The Rain People (1969), The Rains Came (1939), After the Rain (1999 and 2016), Raining Hell (2015), Tears in the Rain (2017). Not a lot of laughs in that bunch.

Filmmakers know that rain can add drama to any scene. It’s been years since I saw the great Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali¸ but I still have mental images of the rain pelting that little Indian village. That was a happy downpour, but such moments are rare. In Japan, Akira Kurosawa was a poet of rain and mist. What could be wetter and more morose than the opening of Rashomon? And then of course there’s Jacques Demy’s 1964 Les Parapluies de Cherbourg, an artfully designed all-singing film set in and around a small-town shop where Catherine Deneuve sells umbrellas. The film begins with the pitter-patter of rain on cobblestones, and the opening credits are almost an umbrella ballet. It’s French and very romantic, and you just know that the ending will be triste.

It’s axiomatic among filmmakers that when you’re on location it rains only when you DON’T need it to. Hollywood is very good indeed at simulating the look of rain with contraptions called Rainbirds. Director Ron Howard once sat down with a reporter from the New York Times to rewatch The Graduate, which he calls “the movie I went to school on.” Midway through, he spotted how Mike Nichols shot the scene in which Mrs. Robinson threatens Benjamin, who has arrived in his Alfa Romeo to take Elaine for a drive. The scene is played out entirely inside the car, with rain pelting the windshield. Howard praised the smartness of Nichols’ staging: “First, it’s a very effective way to make it more claustrophobic, which is the way Benjamin feels. . . . But it’s also by far the cheapest way to shoot this. All you need is one Rainbird.”

Heartbelt good wishes to those suffering from Hurricane Harvey.

Published on September 01, 2017 12:22

August 29, 2017

No Names Changed to Protect the Innocent

We’ve all seen TV programs like Law and Order or the various entries in the CSI franchise.In each episode’s first few moments, before the commercial break (when hucksters try to interest us in fast cars or clean floors or sweet-scented underarms), a heinous crime is committed. The victim—often a lovely young woman who’s gone somewhere she shouldn’t—is set upon by a mysterious someone. She is brutally attacked, but the key details are withheld from us. Uh oh!

After the car or the floor or the armpits are suitably promoted, we’re back with serious-faced cops and crime lab folks, all of them trying to figure out whodunit. There are strong potential leads that come to nothing, because alert professionals are checking out DNA samples as well as suspicious-sounding alibis. Just before the program’s end, the real killer—someone whom we’ve previously dismissed as harmless--is unmasked, with much fanfare. Case closed.

Such shows are as old as television, dating back to Dragnet in the Fifties and Sixties. (I’ve discovered that the original “Just the facts, Ma’am” show started on radio in 1949. Dragnet’s creator and star, Jack Webb, moved it to TV in 1951. It stuck around for eight years, then was revived in 1967 with Webb—in his familiar Sgt. Friday role—now handling cases that involved such updated topics as race riots and LSD. Dragnet and its four-note opening theme (dum da DUM dum) eventually became so widely known that the show was parodied twenty years later on an educational math program for kids, Math Net (1987-92), featuring Sgt. Monday and her sidekick George Frankly solving crimes with the aid of their trusty calculators. But I digress.

On Dragnet, Jack Webb and company wrapped up their sleuthing in 30 minutes. More recent police procedurals tend to last an hour. I think we all enjoy such shows both because they’re cleverly plotted and because we like their take on the world we live in. Yes, on these programs bad things happen to good people. But, in the end, the bad guy (or gal) is caught, and brought to justice. That’s the American way.

I wish it were always so in real life. This weekend’s Los Angeles Times had on its front page an item that shook me to my core. It included a photo of a pretty young brunette named Wendy Halison. I never knew her well, but we were high school classmates. She was honored in a class poll as having the best figure among graduating seniors. In 1968 I was horrified to read that her body had been found in the trunk of her car, not far from where she’d just purchased a hairdryer on sale at a local drug store. She’d been raped and strangled.

The early news accounts cast suspicion on a former boyfriend. I stopped paying attention after that, not really aware that Wendy’s file remained open. Both her parents went to their deaths never knowing who’d killed their daughter. Some thirty years later, with the rise of DNA testing, the four original suspects were officially ruled out. The killer’s identity remained a mystery until 2016, when some dedicated cold-case investigators conclusively linked Wendy’s death to a drifter who died in prison, after being linked to the strangulation of several attractive, dark-eyed young women in the Midwest.

After 48 years, Wendy’s surviving sister now has some answers. But it’s too late for another pretty young woman who died in Burbank in 1969. Though the circumstances of her death strongly resembled Wendy’s, her file has long since been lost. No DNA evidence survives.

Wendy Halison, may you rest in peace.

Published on August 29, 2017 12:36

August 25, 2017

The Godfather Reaches New Heights (What? No Cannoli?)

A movie on the roof. Sounds crazy, no? But both New York and L.A. hipsters are discovering the fun of watching movies on the rooftop of an urban high-rise. Last weekend in DTLA (the cool new acronym for Downtown Los Angeles) I checked out the Rooftop Cinema Club, perched atop a trendy residential building in the rapidly gentrifying South Park neighborhood. It was surprisingly chilly, but the price of admission included (along with a choice of soft drinks) a comfy blanket, plus some spiffy earphones and the privilege of curving my spine into a canvas deck chair. There are also tacos, popcorn, ice cream, and other suitable munchies available for sale: it’s an offer you can’t refuse.

The film I saw on that rooftop was a an all-time classic, The Godfather. Given the subject matter, it would have been more appropriate to watch it in New York, though at least one memorable scene is set in a Beverly Hills mansion. (Yes, I mean the one where John Marley wakes up to find he’s been joined in bed by the severed head of his favorite horse.) I first saw the film, of course, circa 1972, when it was racking up honors, some of them controversial. It won Oscars for Best Picture, Best Screenplay, and Best Actor—the notorious Marlon Brando win that led to a colorfully costumed Sacheen Littlefeather refusing the trophy on Brando’s behalf, in protest of Hollywood’s mistreatment of Native Americans. I had almost forgotten that The Godfather garnered a remarkable three nominations (out of five) for Best Supporting Actor: James Caan, Robert Duvall, and Al Pacino. The latter, though, refused to attend the ceremony, complaining that his role was bigger than that of Brando, and should have been judged as a lead actor performance. The Supporting Actor category was won by Joel Grey, who played the perverse Master of Ceremonies in Cabaret, a film that also won Oscars for star Liza Minnelli and director Bob Fosse.

It's remarkable to me how The Godfather has influenced our language. For the subtitle of my first book, a biography of my former boss Roger Corman, I was inspired to suggest that Roger be called the Godfather of Indie Filmmaking. (My publisher had suggested the much more somber word “Patriarch.”) And who can forget phrases like “go to the mattresses” and “Luca Brasi sleeps with the fishes”? But on this viewing, at a time when our nation can’t stop thinking about the political scene, I was also struck by the film’s commentary on leadership. When Marlon Brando’s courtly Don Vito Corleone sends his henchmen to commit nefarious acts, he apologetically explains that there’s nothing personal about it: business is business. The movie, though, gives the lie to such rationalizations. Don Vito wants to make money, but above all he wants respect, even fealty. And this attitude transfers to the son, Michael (Al Pacino) who ultimately takes over Don Vito’s crime empire. Michael, who at the start of the film has seemed to reject his father’s approach to life, ends up running the show precisely as Don Vito had done. Why, given his American education and his status as a war hero, does he fall back into the old ways? Money? A sense of obligation to continue the family legacy? Yes, but also a playing out of his resentment against his older brothers and the adoptive son (Robert Duvall) with whom he had to share his father’s love.

Ironically, Don Vito had wanted Michael to stay clean—to have a future as a senator or maybe even President. Gangsters spawning politicians? Hmmmm.

Published on August 25, 2017 14:30

August 22, 2017

Seizing the Day with Asimov’s “Nightfall”

Like many Americans, I spent yesterday morning trying to figure out how to watch the eclipse without burning my eyes to a crisp. In SoCal we didn’t get to enjoy the whole phenomenon of the sun totally blocked out by the moon’s shadow. But my neighbors and I did enjoy an ad hoc science lesson while lolling on someone’s front lawn. (They had some nifty little glasses they were nice enough to share. I had my pinhole camera made from a cereal box – thanks, Bernie!)

Like many Americans, I spent yesterday morning trying to figure out how to watch the eclipse without burning my eyes to a crisp. In SoCal we didn’t get to enjoy the whole phenomenon of the sun totally blocked out by the moon’s shadow. But my neighbors and I did enjoy an ad hoc science lesson while lolling on someone’s front lawn. (They had some nifty little glasses they were nice enough to share. I had my pinhole camera made from a cereal box – thanks, Bernie!) The whole experience carried me back to 1988, when I was involved with Julie Corman’s production of a famous Isaac Asimov sci-fi story from 1941. Julie, of course, is Roger’s wife, and a producer in her own right. The story, called “Nightfall,” is set on distant planet illuminated by six different suns. Darkness is non-existent; the possibility of a starry sky is discussed by religious cultists but ignored by the rest of society. The narration begins at a moment of crisis for this society: an astronomic quirk has darkened all the suns but one, which is rapidly being blotted out by another celestial body whose presence no one quite understands. The last time something like this happened, society legendarily devolved into chaos, as its citizens began burning everything they owned in a desperate bid for the comforts of light and heat. Asimov, a professor of biochemistry as well as a science fiction writer, is at his most vivid in describing the progression of the eclipse. Early on, referring to the one still-functioning sun, he writes, “Beta was chipped on one side! The tiny bit of encroaching blackness was perhaps the width of a fingernail, but to the staring watchers it magnified itself into the crack of doom.” Soon afterwards, we learn that “Beta was cut in half, the line of division pushing a slight concavity into the still bright portion of the Sun. It was like a gigantic eyelid shutting slantwise over the light of a world.” Finally, as the darkened sky reveals a brilliant star cluster, “thirty thousand mighty suns shone down in a soul searing splendor that was more frighteningly cold in its awful indifference than the bitter wind that shivered across the cold, horribly bleak world.” No wonder the planet’s inhabitants go beserk.

It’s dazzling writing, but Asimov is not especially strong when it comes to action and characterization. The entire story takes place inside a fortress-like lab where scientists try their best to understand (and survive) what’s about to happen. We get several perspectives, but there’s not the sort of rich human drama that the screen demands. We who were working with Julie Corman on writer/director Paul Mayersberg’s screen adaptation all knew that the eclipse would be the film’s climax, but it seemed essential to explore the society that would be turned upside down by the crisis in the heavens. We needed to know these people’s lifestyles and belief systems. And it would be nice to have a love story.

Unfortunately, Mayersberg’s Nightfall gets carried away with its view of an elaborate and somewhat kitsch-driven world, full of exotic rituals and really bad wigs (one worn by the film’s miscast star, TV actor David Birney). And we Cormanites certainly didn’t have the special effects budget to carry off the climax that Asimov’s drama demands. Leonard Maltin pronounced the finished result a BOMB, but Roger Corman—always good at hype—advertised that it was based on “the best science fiction story of all time. And in 2000, Roger sent David Carradine and company to India to try to make Nightfall once again.

Published on August 22, 2017 16:32

August 18, 2017

Meet “Meet John Doe”

Today, while questions of political leadership are dominating our national conversation, Frank Capra’s 1941 Meet John Doe has an unexpected resonance. Though the details of this Robert Riskin comedy-drama are eccentric and even bizarre, the story has some relevant things to say about ethics in the world of mass media.

Meet John Doe starts out with the takeover of a popular urban newspaper by a tycoon (Edward Arnold) looking to score political points. His goal for his paper is the sort of slash-and-burn journalism practiced today by Rupert Murdoch and sons. Journalistic standards be damned: what had been The Bulletin is now to become “The New Bulletin – A Streamlined Paper for a Streamlined Era.” On the chopping block are most of the newsroom’s staff, including feisty Ann Mitchell (Barbara Stanwyck). Furious at being canned and then expected to cough up a final column, she invents a heart-tugging letter from one John Doe, a jobless man who plans to jump to his death from the City Hall tower on Christmas Eve in a protest against society’s failings. Yes—fake news at its finest.

The outcry from the public leads Ann and her editor to search out a John Doe stand-in, someone who can be manipulated into keeping readers interested. Many out-of-work men apply, claiming to have written the letter. But the nod goes to Gary Cooper’s John Willoughby, a former baseball player with a wounded wing, He admits the letter is not his, though he badly needs a job. Ultimately his brawny good looks and his aw-shucks manner make him an appealing John Doe substitute. This is yet another of Cooper’s great man-of-the-people performances, perhaps his finest. (He was to win a Best Actor Oscar for another 1941 common-man role, that of the heroic Sergeant York.)

Now that a fake John Doe is on the team, Ann feeds him talking-points about how people need to be more neighborly to one another. Too honest a guy to accept the subterfuge for long, he goes on the lam with harmonica-playing buddy Walter Brennan, intending to leave John Doe far behind. A stop at a rural diner, though, persuades him that his John Doe persona is needed by the American public. In fact, everyday folks all over the US of A are spontaneously founding John Doe Clubs as a way of increasing neighborliness in local communities. Despite it all, he’s a hero.

This is when, of course, the nefarious newspaper publisher comes in. Determined to take advantage of John Doe’s hold on the heart of the common man, he launches a huge rally at which Cooper’s character is expected to endorse him and his brand-new political party. His ultimate goal: the White House. But his hope of populism-run-amok is foiled when Willoughby again refuses to be a party to the deception. The publisher retaliates by spreading the word that John Doe is a fake. Which leads to a thoroughly-humiliated Cooper deciding to jump off the tower for real. As his suicide becomes imminent, various forces align to save his life. Care to guess if there’s a happy ending?

Frank Capra has always been revered for his warm depictions of American life. In this mid-career work (one of two films he directed for Warner Bros. after leaving his home at Columbia Pictures), he showed his skill with actors, including those in supporting roles. It’s strange, though, to see a Hollywood film so obsessed with the notion of suicide. And Capra’s iconic faith in common folk at times seems misplaced. Still, in this day and age, seeing people stand up to bullies is a major treat.

Published on August 18, 2017 10:52

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers