Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 81

January 30, 2018

Don't Call Me By Your Name -- I'll Call YOU!

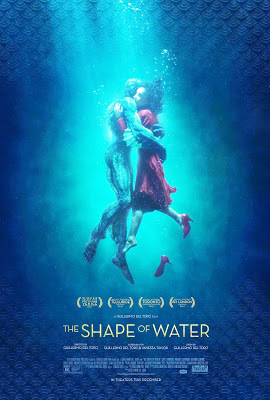

The smart money in this year’s Oscar race seems to be on either The Shape of Water or Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri. It’s hard to say which has the better chance, but my guess is that voters of a more cynical bent will opt for Martin McDonagh’s bitter (yet fascinating) story of loss and retribution, while the optimists in the Academy will prefer Guillermo del Toro’s uplifting (yet bizarre) otherworldly love story. In del Toro’s telling, the love of a human woman and a sea creature certainly has an ethereal side. He deftly balances this, however, with a lot of real-world squalor and Cold War anxiety. That’s my problem with another of this year’s contenders. It’s so gorgeous, so swoon-worthy, that it doesn’t seem part of real life at all.

I’m talking, of course, about Call Me By Your Name, a film that’s all-aquiver with the intensity of its lovers’ passion. I remember hearing about this film after last year’s Sundance: from the start it was seen as an awards contender. And perhaps in a different year it would be at the top of the heap, at least in part to make up for the fact that in 2006 the Academy denied a Best Picture Oscar to another gay love story, Brokeback Mountain. I was fascinated by the inarticulate cowboys in that film. And I can’t deny that the actors in Call Me By Your Name are both attractive and convincing. Timothée Chalamet, the youngest man in many years to be up for a Best Actor Oscar, is a powerful presence, one whose emotional highs and lows seem to leap off the screen. (It’s completely irrelevant, but I’m enthralled by the fact that his mother’s brother, director Rodman Flender, was a colleague of mine at Concorde Pictures. I always thought Rodman had a distinctive look and manner, and now I see it runs in the family.)

Still, I must say I found this film hard to take, for reasons that have nothing to do with moral outrage. Under the guidance of Italian director Luca Guadagnino, it’s so slow, so limpid, so sensitive. Yes, the photography is beautiful: it captures lives that are so blissfully sensuous that they seem to have nothing to do with the world as I know it. It’s the height of summer in a small Italian town. The Perlman family are ensconced in their 17thcentury villa, where they have no obligation to do anything but read books, play music, swim in the river, and think deep thoughts. The father (well played by Michael Stuhlbarg) is a renowned scholar of archaeology, so he occasionally waxes poetic about the alluring beauty of Greek statuary, but he seems to have no pressing duties. Seventeen-year-old son Elio (Chalamet) rides around town on a bicycle, half-heartedly experiments with sex with a local girl, and then cuddles on a sofa with his parents while his mother reads aloud from a German novel she translates on the spot. (The Perlmans have the maddening habit of switching from English to French to Italian in casual conversation.) Then a hunky grad student named Oliver (Armie Hammer) arrives, and Elio is totally smitten.

Soon amid all those perfect al fresco meals and smoothies made by the maid from perfect peaches plucked from a perfect backyard orchard, Oliver and Elio are taking tentative steps to acknowledge what they feel for one another. And the world’s most understanding parents are quietly cheering them on. Actually, Oliver – though pretty -- was for me pretty much a blank. I suspect Timothée Chalamet’s Elio can do much better.

Published on January 30, 2018 13:54

January 26, 2018

The Stowaway: A Story Disney Would Not Have Told

A few weeks ago, newspapers everywhere reported the passing of Doreen Tracey, best remembered as one of the fresh-face youngsters who sang and danced their hearts out on The Mickey Mouse Club. I remember Doreen well. Like all the girls my age (and maybe the boys too) I had my special favorites. I liked Darlene, Annette, and Bobby. That left my little sister with Karen, Cubby, and Doreen. Neither of us was too crazy about Sharon, despite her outstanding dance skills. But all of those squeaky-clean kids served as role-models for us mere mortals. How we longed to be in their tap shoes! (Who knew that years later spunky Darlene would be sentenced to prison, along with her third husband, for a check-kiting scheme?)

One daily feature of the Mickey Mouse Club, aside from those frolicking Mouseketeers, was a live-action serial in which young people did brave and exciting things, usually in the great outdoors. Like racing horses, fighting off rustlers, and solving crimes. Remember, for instance, “Corky and White Shadow”? And “The Adventures of Spin and Marty”?

When I look back at the programming of that era, I realize one thing that never occurred to me in the 1950s. Not only was everyone on-screen white, but it was rare to see any performer or character who strayed into ethnic terrain of any sort. No Jews, of course, needed to apply. There was much comment, even back in the day, that Annette Funicello was the single most popular Mouseketeer, even though she (given her name and appearance) was overtly Italian-American. Everyone else, though, had WASP surnames like Burgess and Pendleton and Burke, or the occasional O’Brien and Gillespie. Original Mouseketeer Don Grady, whom I knew slightly in later years, was born Don Agrati, but his Italian last name disappeared when he started his showbiz career.

I bring this up because my colleague, Laurie Gwen Shapiro, has just published a rollicking true tale of derring-do. It’s called The Stowaway: A Young Man’s Extraordinary Adventure to Antarctica. And it’s all about a seventeen-year-old lad who in 1928 persistently stowed away on sea-going vessels, until he could finally fulfill his dream of joining Admiral Byrd on his historic trip to the bottom of the world. It’s a thrilling story, but not one that Disney would have pursued back in the Mickey Mouse Club days. An essential fact about this young stowaway, Billy Gawronski, was that he was Polish-American, the son of immigrants, and had a deep cultural connection to the land of his parents’ birth. When Shapiro stumbled upon his story, it appealed to her partially because she too (a product of New York’s Lower East Side) knew what it was like to come from immigrant stock: the pride, the parental expectations, the urge to prove oneself in the wider world.

One of the fascinating details I learned from Shapiro’s book was that at the outset of the voyage to Antarctica from Hoboken’s harbor, there were no fewer that three stowaways. The one who managed to remain undetected the longest was an African-American named Bob Lanier. Though for a time Lanier was accepted onboard as a crew member, racism reared its ugly head and he was eventually sent back home, long before reaching his dream destination. Despite several attempts, he never managed to walk on Antarctica. It took another 12 years, until 1940, for a young navy man named George Gibbs to be the first African American to visit Little America.

That’s one more story that Walt Disney and The Mickey Mouse Club of my youth would never have chosen to tell.

Published on January 26, 2018 10:34

January 23, 2018

It’s a Wonderful Life for Wonder Woman and her Peers

As I write this, I don’t yet know what films have been nominated for 2018 Oscars, which are due to be presented on March 4. But it’s a safe bet that the word “Wonder” will appear somewhere in the list of nominees. In one of those curious coincidences that Hollywood is known for, there are five major movies from 2017 whose titles are literally wonder-ful. First of all there’s Wonder, based on a schmaltzy children’s novel about a boy with a grotesquely misshapen face. For the much-lauded film version, adorable Jacob Tremblay (from Room) underwent hours of elaborate makeup, including prosthetics, in order to portray the central character, with Julia Roberts and Owen Wilson as his concerned but loving parents.

This year’s inevitable Woody Allen project, set at Coney Island in 1950s, is called Wonder Wheel, with the title of course referring to the amusement park’s iconic Ferris wheel. This is solemn, sensitive Woody at work: Kate Winslet, Jim Belushi, and Justin Timberlake are featured in what sounds like a mawkish story of love, loss, and the woes of the downtrodden.

I’ve not had the opportunity to see Wonderstruck, but it has a marvelous pedigree: the director is Todd Haynes; lead actors include Julianne Moore and Michelle Williams; the music is supplied by the always interesting Carter Burwell (the Coen Brothers favorite who has gotten major attention this year for his gripping Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri score). Writer Brian Selznick, whose 2007 work was adapted into Martin Scorsese’s genuinely wondrous Hugo, wrote the screenplay based on his own novel. The story rotates between two separate quest narratives involving children. The one set in 1927 is shot in black & white, using a number of silent film techniques. Sounds amazing—why was this not in theatres longer?

Then of course there’s the international blockbuster, Wonder Woman, which I finally chanced to see. As I understand it, the sex goddess of the DC Comics universe had a long route to her big-screen debut. Back in the 1970s, of course, she was played by the zaftig Lynda Carter in a kitschy TV show I never bothered to watch. More recently, a number of famous filmmakers (Joel Silver and Joss Whedon among them) wanted to bring her to the big screen. Sandra Bullock, Catherine Zeta-Jones, and others were considered for the lead, but no one could seem to decide if a Wonder Woman movie should be action-comedy or drama, set in a fantasy world, the historic past, or the present day. What’s fascinating about the current Patty Jenkins production is that it contains a bit of everything—and somehow it works. The opening scenes set in the island nation of the Amazons looks like an upscale version of a Roger Corman barbarian-queen flick. Then suddenly we’re in the middle of a World War I movie, played somewhat realistically until we find ourselves in the presence of a super-villain with mythological credentials There’s some sexy banter, some fish-out-of-water humor, and a poignant lost love. And throughout it all, star Gal Gadot retains her dignity and her charm while deflecting bullets Brava!

But this was also the year of Professor Marston and the Wonder Women, purporting to be a real-life origin-story for the Wonder Woman comic character. Who knew that a psychology professor who significantly contributed to the development of the polygraph also came up with the idea of a female superhero? And who knew that he was inspired by the wife and the mistress with whom he lived in a polyamorous relationship? Now that’s a movie I need to see.

Not so wonder-ful update; poor Wonder Woman was left out in the cold (in a very skimpy costume). The only “wonder” on the Oscar nomination list was a nod for Hair and Makeup on the film Wonder.

Published on January 23, 2018 12:57

January 19, 2018

This is Not a Test: Fail-Safe and Dr. Strangelove

Part of my mind these days is deep in the mud, in sympathy for those unfortunate folks in Montecito, California who’ve endured both fire and rain. (I doubt many of them are looking forward to seeing the film Mudbound.) And another part is frankly terrified by what almost happened in Hawaii, triggered by a false ballistic missile alarm. No harm was ultimately done, except for a lot of jangled nerves among those island-dwellers mistakenly alerted by the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency. But in the wake of this very human error—not to mention the currently strained relations between the U.S. and nuclear rogue state North Korea—NPR broadcast an interview that made my skin crawl.

The interview was with William Perry, who for three years served as Secretary of Defense in the Clinton White House. In 2013 he founded the William J. Perry Project, a non-profit effort to spread the word about the dangers posed by nuclear weapons. Perry clearly knows whereof he speaks. During his White House tenure, he was aware of three instances in which a small human error could easily have touched off World War III. In one case, he accidentally uploaded test software in such a way that it seemed like an announcement of a genuine nuclear attack. Fortunately, an alert official caught the error and reversed it without bringing it to the attention of the U.S. president, who’d theoretically have about 5 minutes to decide on a retaliatory missile strike. In Perry’s era, something similar happened in Russia, but the officer in charge was severely reprimanded for avoiding the involvement of the Russian leader. As Perry makes clear, we’re all too vulnerable to the possibility of a spur-of-the moment nuclear decision made by a single individual, one who might not be willing to accept the possibility that an announced enemy missile strike is actually a careless mistake.

Back in 1964—a nervous time that I remember well—not one but two movies dramatized how the Cold War might heat up as the result of an accidental nuclear strike. Fail-Safe, a thriller based on a popular novel, explored what would happen if a U.S. bomber were accidentally ordered to drop a nuclear warhead on Moscow. This serious and somber film, directed by the great Sidney Lumet, featured an all-star cast, including Henry Fonda as the President of the United States. Advertising posters featured an ominous line: “Fail-Safe will have you sitting on the brink of eternity!”

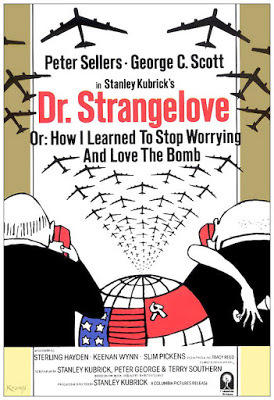

This was a time when Cold War paranoia was highly visible on movie screens. Along with Fail-Safe, 1964 saw the release of John Frankenheimer’s equally starry Seven Days in May (“United States military leaders plot to overthrow the President because he supports a nuclear disarmament treaty and they fear a Soviet sneak attack.”) But a third 1964 film approached the threat of nuclear disaster in an entirely different spirit. Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb was loosely based on a British thriller called Red Alert (aka Two Hours to Doom). The British novel was dead serious in positing that a U.S. Air Force general, a victim of paranoid delusions, might unleash the first strike in World War III. But, given the appearance in that same year of grim films like Fail-Safe, writer-director Stanley Kubrick wanted to try something completely different. That’s why Dr. Strangelove shocked the American public by turning the threat of nuclear war into outrageous black comedy.

Dr. Strangelove dared to make fun of scientists, generals, nuclear weapons, and the U.S. president himself. Moviegoing has never been the same since.

Published on January 19, 2018 15:34

January 16, 2018

The 2017 National Film Registry: A Study in Black and White

On the day we set aside to commemorate the birth of Dr. Martin Luther King, I looked back at the 2017 list of films chosen for inclusion on the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry. The list, always announced in the waning days of the year, annually contains the names of 25 films that the U.S. government has pledged to preserve because of their historical, cultural, or aesthetic significance. Predictably the current list contains a blockbuster epic (Titanic), a classic thriller (Die Hard), an innovative aesthetic experiment (Memento), and a sentimental favorite (Field of Dreams). But—at a time when the question of racism has taken on some urgency—I was struck by how many of the selected films grapple with racial and ethnic bias.

Back in 1947, Gregory Peck and company confronted the prevalence of post-war American anti-Semitism in Gentleman’s Agreement. This Elia Kazan-directed film (one that meant a great deal to my own parents) is on the 2017 list, along with several movies exploring Latino barrio life. But—aptly for Martin Luther King Day—I noticed no fewer than four films that give context to our nation’s struggles with the divide between black and white America.

It was gratifying to be the one who told Karen Sharpe Kramer that her husband Stanley’s greatest hit, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, had made the list. When this film was released in late 1967, a decade after the first baby-steps of the Civil Rights movement, college-age Americans tended to scoff. For them the story of affluent and liberal-minded white parents (Spencer Tracy, Katharine Hepburn) who eventually give their consent to their daughter’s union with the world’s most perfect black man (Sidney Poitier) seemed much too corny to be of interest. Still, plenty of people, in and out of the Deep South, were outraged. But the movie’s triumph at the 1968 box office seemed to help move the needle in terms of the general public’s reaction to interracial love. A reviewer in the Tulsa Tribune talked about its impact: “What we get is a 1968 reaction to a social question by a range of people representing the full spectrum of possibilities—from the bigot with a totally closed mind to [the] ultra liberal who sees no question. . . . The film could not have been successfully released nationally five years ago; it will be hopelessly out of date five years hence.”

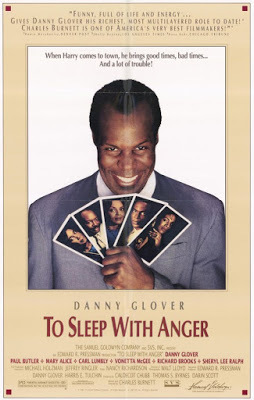

Also on the 2017 list is Charles Burnett’s raw 1990 drama of black life, To Sleep with Anger. This much-admired indie has been honored by film buffs, and Burnett (now 73) received one of the Motion Picture Academy’s honorary Oscars last fall for his body of work. But as an African-American director he has never had access to the big projects his talents seem to warrant. A more prominent African-American filmmaker, Spike Lee, has a spot on the list too, for his powerful 4 Little Girls documentary (1997) about the 1963 firebombing of a black Birmingham Church, leading to the deaths of four small children.

I suspect not many people today associate Walt Disney’s charming Dumbo (1941) with racial politics. And my own favorite memory of Dumbo, aside from its literally uplifting ending, is the genuinely phantasmagoric segment known as “Pink Elephants on Parade.” But there was a time in the 1960s when, as I understand it, Dumbo couldn’t be publicly shown because the “Jim Crow” characters in the “When I See an Elephant Fly” number were taken as offensive black stereotypes. True, they were voiced by a famous all-black choir, but I can’t see them as anything but lovable.

Published on January 16, 2018 16:44

January 12, 2018

John Manderino: Here There Be Monsters

My 2017 book, Seduced by Mrs.Robinson , gave me the opportunity to praise in print a recent memoir by a Maine-based writer named John Manderino. His Crying at Movies was an inspired comic summation of his own life, with each key episode tied to a movie-going memory. For instance, after his first youthful sexual encounter went badly, he sought performance tips from the lusty Swedes by watching Elvira Madigan. (Alas, it didn’t help.) Then, when he was a lowly college sophomore, a senior asked him out because she adored The Graduate and thought he resembled Dustin Hoffman. Manderino was not flattered. In his mind, “Benjamin was short and looked like a rodent.” Still, he was attracted to the young woman, and so he managed to convince her that he was indeed sweet, sensitive, and depressed, just like Ben. In the next chapter we found them in bed together.

Manderino wrote Crying at Movies in 2008. Eight years later, he published another short story volume, one that pays an eccentric kind of tribute to things that go bump in the night. It’s called But You Scared Me the Most . The title comes from a Randy Newman tune, and the collection riffs on monsters, both those encountered on a movie screen and those who surround us in everyday (and every-night) life. More often than not, we are the monsters ourselves, learning to proudly fly our freak flags, no matter who is watching. There is, for instance, the eleven-year-old boy who celebrates Halloween by turning into a vampire. And, in a delicious story called “Wolfman and Janice,” a suburban housewife joins her spouse by transforming into a werewolf. (By this point, he’s already eaten the neighbor’s cat.)

Some of the stories explore characters who are shaped by their interaction with screen monsters and other grotesques. The Wizard of Oz, Frankenstein’s monster, Boris Karloff as The Mummy, and The Creature from the Black Lagoon all make appearances, as do such long-ago pop culture icons as Kukla (of TV’s Kukla, Fran, and Ollie), a bickering Barbie and Ken, and Señor Wences’ creepily literal hand-puppet, Johnny. In such stories a human character’s response to these famous fantasy figures makes clear to us the challenges and confusions within his (or her) own life. But Manderino also sometimes gets into the head of a fantasy being, like Bigfoot (or – charmingly – an aged Nancy Drew, still struggling to sleuth out things that have gone missing.)

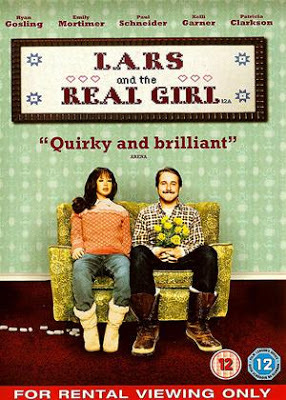

One of the earlier stories, “A Certain Fellow Named Phil,” begins with the first-person confession of a murder. The victim, though, turns out to be an inflatable sex doll. I’m wondering if John saw, and enjoyed, my favorite film on this topic, 2007’s Lars and the Real Girl, then gave his version a more morose ending. The final story of the collection, “The Witch of Witch’s Woods,” captures the eerie uncertainty that was an attraction of The Blair Witch Project. But the most cold-blooded story of the lot, the blandly-titled “Bob and Todd,” may contain nothing menacing at all. In this tale of a hitchhiker picked up along a highway, the driver may or may not be hauling his wife’s body along with a load of athletic shoes. That’s for him to know and his passenger to obsess about. I can imagine this as a one-act play, something on the order of Albee’s The Zoo Story. Or, of course, it could be the genesis of a very cool and creepy movie.

I’ve never met John Manderino in person, and that’s probably a good thing. I think he’d scare me the most.

Published on January 12, 2018 15:14

January 9, 2018

"Phantom Thread": The Muse Wears Black

Fashion, as Sunday night’s Golden Globes “black-out” has shown us, can be a potent political statement. All of those gorgeous movieland fashionistas who purged color from their party frocks certainly made a point about female solidarity and the need to end sexual harassment now. Though many of their outfits were prim by Hollywood standards, some barely-there numbers seemed, confusingly, to invite the sort of sexual attention their wearers professed themselves to eager to decry. Still, I appreciated the monochrome aesthetics of the gathering, and admired designers’ flexibility in coming up with so many all-black looks on very short notice.

But enough about the vagaries of fashion, Hollywood-style. Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Threadlooks at the world of dressmaking with a different eye. He’s interested in the life of a London haute-couture house, one charged with dressing the cream of international society from cradle to grave. Heiresses and royals descend on the house of Woodcock to be fitted for exquisite gowns, day-dresses, and wedding ensembles, each garment a hand-sewn and timeless masterpiece. That’s the irony: in the eyes of designer Reynolds Woodcock (Daniel Day-Lewis) and his staff, the dresses are far more important than the VIPs who will wear them. In one of the movie’s most exhilarating scenes, a fabulous green ensemble is deftly rescued from the drunken body of the wealthy woman who’d commissioned it. In Woodcock’s eyes, she simply isn’t worthy of being entrusted with one of his wearable works of art.

Phantom Thread takes place in the 1950s, when Post World War II Europe was celebrating a return to high standards of luxury. Fabric is sumptuous; lines are classic. There’s no desire to shock or surprise: that iconoclastic spirit would wait until the following decade, when such rebels as André Courrèges and Mary Quant democratized fashion, hiking hemlines and turning style into something for the very young and very fit. For the wearer, the only surprise about a Woodcock ensemble would be discovering the cryptic written message that the designer tends to tuck into the occasional hem, a secret memo to himself and (perhaps) to posterity.

In Phantom Thread there’s an enigmatic young woman, played by Vicky Krieps, who (both literally and figuratively) finds and decodes that message. Alma—whose name means “soul’—is a tall, lean figure, first glimpsed stumbling awkwardly while serving breakfast in a country tea-room. Her origins are obscure, as are her motives. But from the first she seems willing enough to fall under the spell of Woodcock, who sees in her proportions his aesthetic ideal. She quickly becomes his model and his muse, but is not afraid to announce her own tastes and to chafe against his more high-handed behavior. (Woodcock’s sphinx-like sister and business manager, ominously played by Leslie Manville, completes a strange isosceles triangle.)

Midway through the film, Alma seems to be taking over the story, daring to assert her own will in ways we wouldn’t have expected. Her behavior is so boldly capricious that Phantom Thread starts to seem like a different film, maybe one marked by a tinge of the supernatural. Is Alma, perhaps, meant to be viewed as an allegorical figure in a tale modeled after Poe or Henry James? Certainly, it’s easy to see her as the slippery muse who holds the artist’s fate in her hands. But Anderson’s characters are far too alive to ever be reduced to mere abstractions. The fact that they slip away from us does not reduce their humanity. (Nor, of course, does the apparent fact we’re about to lose Day-Lewis to retirement. We need him too badly to let him go.)

Published on January 09, 2018 13:42

January 5, 2018

Katharine Graham Marches Forward with the Washington Post

It’s hard to think of the Washington Post as a small-town newspaper that cozied up to politicians in power. But that’s what it was when Katharine Graham took over the reins of the family media company after the death of her husband. The paper had been published by Graham’s father, Eugene Meyer, since he bought it at a bankruptcy auction in 1933. In 1946 he handed over the paper to his son-in-law, Philip Graham. But Graham’s 1963 suicide—following a romantic scandal and a nervous breakdown—led to his widow, Katharine, taking The Post into her own hands. As a female raised largely by wealthy absentee parents she had no great faith in her own abilities. Still, she ultimately rose to the occasion, hiring Ben Bradlee as editor of the Washington Post and standing by him as the Post became a major player in the publication of the Pentagon Papers and, a few years later, in the Watergate investigations that ultimately led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon.

Every movie buff knows All the President’s Men, the 1976 Watergate thriller that turned Post reporters Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward into action heroes uncovering presidential dirty tricks. But even those of us who lived through the 1971 disclosure of the top-secret Pentagon Papers by Daniel Ellsberg may be a bit fuzzy in our recollections of what this scandal was all about. The papers, from the U.S. Department of Defense, traced the history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1967, proving the extent to which various presidents and their cabinet officers had lied to Congress and to the American people about the impossibility of victory in Southeast Asia. When the New York Times, which had begun publishing the papers, faced a legal injunction, the Washington Post stepped into the fray.

What makes this a great subject for a movie is the fact that Katharine Graham treasured her long friendships with such political leaders as Robert McNamara, who’d been secretary of defense under presidents Kennedy and Johnson. We see at the very beginning of the film McNamara—aboard an airline leaving Vietnam—candidly telling RAND analyst Ellsberg that the war is unwinnable, before announcing at a press conference that progress is being made. To forge ahead with the publication of the Pentagon Papers, Graham had to commit to offending McNamara and others, in the name of journalistic candor. It was her respect for Bradlee’s brash but principled journalistic standards that tipped the balance.

Steven Spielberg decided to make this film last March, on a break from his ambitious sfx-heavy videogame movie, Ready Player One. To play Graham and Bradlee, he recruited two of Hollywood’s finest, Meryl Streep and Tom Hanks. They make fine sparring partners, in a film that offers real lessons for today. There are lots of quaint 1970s touches in The Post—telephone booths, news stories banged out on typewriters, linotype machines that spit out printed newspapers, bulky documents that must be copied page by page in Xerox machines. And, of course, few women in newsrooms, and even fewer in boardrooms. But in today’s era of “fake news” accusations, it’s all the more heartening to focus on a time when journalists took on the government, cluing in the American people to what was secretly being done in their names. Freedom of the press is one of the sacred pillars on which our government rests, and I for one thank Spielberg for reminding us of the price we pay for cronyism and for burying our heads in the sand.

Trivia time: The classic Sousa march, “The Washington Post,” was written in 1889 for the awards ceremony celebrating the winners of the newspaper’s essay contest.

Published on January 05, 2018 12:53

January 2, 2018

There Will Be Blood: “Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri”

Last week, by a strange quirk of the calendar, I spoke at my local library following a screening of The Graduate, and then was whisked off to watch a much newer movie, Martin McDonagh’s 2018 awards contender, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri. By now—in the course of writing, publishing, and promoting my Seduced by Mrs. Robinson: How The Graduate Became the Touchstone of a Generation—I must have seen The Graduate at least 150 times. There are various ways to measure a motion picture’s greatness, but the fact that I can watch a fifty-year- old movie 150 times and still get a kick out of it surely signals that it’s far better than average. After all this time I continue to find The Graduate both funny and endearing. It speaks particularly to Baby Boomers, who see it in the context of an especially turbulent period of American history, but I’ve recently chatted with young men and women who find in the situation of Benjamin Braddock an accurate encapsulation of any young person’s desperate attempt to make his or her voice heard.

That being said, Benjamin’s angst in The Graduate is pretty mild stuff. Yes, he’s suffering from a failure to communicate with his parents and their cronies. He doesn’t know what he wants out of life, though he’s trying at all costs to avoid going into plastics. He’s a smart, successful, affluent kid who doesn’t appreciate the gifts he’s been given, and can only grasp at the hazy fact that he wants his future to be “different.” And the other unhappy people in The Graduate, like Mrs. Robinson and her daughter Elaine, are equally lacking in the will to face their situations squarely and to arrive at solutions that really work.

In Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, the problems are far bigger and far more resistant to solutions. Ebbing, Missouri is clearly more hard-scrabble than Beverly Hills, California, but it’s not economic hardship that darkens the lives of these characters. Instead, they suffer from a daunting array of challenges, facing not so much existential angst as genuine anguish. Among the people of Ebbing, Missouri, life is truly grim: there’s a fatal illness and a child’s brutal murder to contemplate, along with one character’s possible PTSD and another’s deeply ingrained propensity to violence. Ebbing is a place filled with more trauma than anyone knows what to do with, though some of the locals deal with tragedy via a surprising sweetness and others with a dark but very funny sense of humor.

Martin McDonagh started out as the playwright responsible for such bleak dramas as The Lieutenant of Inishmore, then segued into filmmaking with 2008’s In Bruges, which he both wrote and directed. His trademark is an intermingling of brutality with dark humor: In the course of In Bruges he uses the teaming of hitmen played by Colin Farrell and Brendan Gleeson to hilarious effect. A second feature film, Seven Psychopaths, was far less successful, I’m told. Now, though Irish to his core, McDonagh has set up shop in the American heartland, melding a profanely grieving mother (Frances McDormand) with an unusual good cop/ bad cop combo (Woody Harrelson and Sam Rockwell) to explore motifs of anger, retribution, and forgiveness in a most unlikely way. McDonagh is certainly not everyone’s cup of blood. Some critics have called this movie overrated, and feel its look at America is superficial and imprecise. But one thing’s for sure. Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Montana.is not a film easily forgotten. And that in itself is a form of greatness.

Published on January 02, 2018 09:26

December 26, 2017

At the Heart of “The Shape of Water”

The Los Angeles Timesreview of The Shape of Water compared this mesmerizing new film to Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast as well as an important childhood influence for writer-director Guillermo del Toro, The Creature from the Black Lagoon. Del Toro, best known for the equally phantasmagoric Pan’s Labyrinth, is an expert on finding the reality in a fantasy world. Perhaps his comfort in combining the grotesque with the mystical comes from his Mexican Catholic upbringing: his native land is a place where the Day of the Dead is celebrated and skeletons romp through the fine arts in all their manifestations.

Curiously, The Shape of Water made me think of an equally watery but far sunnier film, Ron Howard’s Splash. This 1984 romantic comedy, which made a star out of Tom Hanks, introduces a mermaid (Daryl Hannah) who comes ashore in Manhattan in search of a special young man who’s terrified of water. After various escapades, some of them involving a mad scientist, the movie builds to an undersea conclusion that’s charming and optimistic. In The Shape of Water, though, sunlit New York City is replaced by a grim and dreary Baltimore, where scientists and military types are conspiring in a retro-futuristic lab to study a captive being cryptically called “the asset.”

The era, crucial to The Shape of Water, is the late 1950s, a time when Americans were panicky about the success of the Soviet space program. The Cold War tensions underlying the film provide its external drama: there are creepy government operatives (Michael Shannon is the chief one) calling the shots, and equally creepy Russki spies lurking about. But del Toro, whose eye for picturesque visuals is uncanny, also gives us the flip-side (what a terrifically retro word!) of the late 1950s. Shannon’s character lives in a cheery suburban home with wife and kiddies straight out of Dick and Jane. Late in the film he treats himself to a glossy “teal” Cadillac with tail fins out to there. TV sets are ubiquitous, featuring scenes from Dobie Gillis and ads for JELL-O. Percy Faith’s lush rendition of “Theme from A Summer Place” is a highlight of the soundtrack.

Against all this candy-colored domesticity, del Toro sets the lives of several 1950s misfits. There’s Zelda (Octavia Spencer), one of a fleet of cleaning ladies who clean up the muck and the pee of their betters. As a black woman, she’s used to being rendered invisible. There’s Giles (a highly sympathetic Richard Jenkins), an artist who feels himself being shoved aside for reasons both professional and personal. And, crucially, there’s Elisa, who is Zelda’s co-worker and Giles’ neighbor in a strange and beautiful old building above a dying movie palace. As unforgettably played by Sally Hawkins, Elisa’s an orphan who’s been rendered mute by some mysterious childhood mishap. Though she can’t speak, she can hear and understand all that goes on around her. Precise and self-contained, she’s also at base a dreamy and creative soul. She and Giles bond over old romantic movies, tap-dancing, and pie. Her personal soundtrack is dominated by Alice Faye soulfully warbling “You’ll never know how much I love you.” When her heart is captured, she gives herself completely.

Finally there’s “the asset,” the supernatural creature whose presence propels all the action. Between him and Elisa there’s instant communion, with no need for speech. He’s strange, disturbing, and gorgeous, just right for a mysterious fairy tale in which all the participants seem totally real.

Published on December 26, 2017 10:11

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers