Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 80

March 6, 2018

Surprise! (Part Deux): How Hollywood Celebrates Itself

Frances McDormand looking golden

Frances McDormand looking goldenAs I’ve noted in this space, I love movies that have the ability to surprise me, without resorting to cheap tricks. And I love watching live-action television shows (NCAA basketball championship games, Olympic gymnastics competitions) in which the outcome is by no means certain. That’s part of why I’ve always loved watching the annual Academy Awards ceremonies: the fabulous dresses! the clever quips and heartfelt thank-yous! the oh-my-god-I- don’t-believe-it gaffes! How well I remember sitting around the TV set with my family, rooting for movies I wasn’t old enough to see. When Paddy Chayefsky’s modest little slice-of-life drama, Marty, triumphed over such big schmaltzy romances as The Rose Tattoo and Love is a Many-Splendored Thing, there was joy in my house.

Times, of course, have changed. In my childhood, if you liked movie awards shows, the Oscars were pretty much the only game in town. And I was genuinely excited about the outcome, whatever it turned out to be. Today, so many craft guilds, film-support organizations, and critics’ groups weigh in from December through February that by Oscar night I suspect we all feel a sense of déjà vu. And -- though everyone agrees that there’s really no such thing as a “best” performance -- we find a surprising degree of unanimity when it comes to the major prize-winners. Whatever you think of Sam Rockwell, Allison Janney, Gary Oldman, and Frances McDormand (all of whom have been honored week after week in the run-up to the Oscars), it would have been surprising and delightful to see someone else accepting the golden trinket in their stead. (Sally Hawkins, this one’s for YOU!)

But I’ve got to go easy on Frances McDormand, because her unfiltered presence on the stage was (as always) a genuine tonic. Here’s a woman who seems (both at the movies and in real life) to say what she thinks, without the need for a carefully-polished veneer. She’s as different as can be from the Hollywood glamour queens of old, much as I have always enjoyed seeing them strut their elegant stuff. No wonder writer-director Martin McDonagh chose to put her at the center of his first American film, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri. She plays a woman whose emotions have been rubbed raw by grief, but who probably wasn’t easy to live with at the best of times. On screen in this film, she’s ornery, obnoxious, and funny. On the Oscar stage she was a bit less ornery, definitely not obnoxious, and still funny—as well as a great cheerleader for the issue that the Oscar folk had been tiptoeing around all evening, that of equal and respectful treatment of women. Yes, the show nodded in the direction of the #MeToo movement at several junctures—pointedly referring to “women and men” instead of including women in the familiar second position, giving a cameo appearance to Weinstein whistleblowers Ashley Judd, Annabella Sciorra, and Salma Hayek. But McDormand seemed ready to take actual action. Aside from insisting that ALL the female nominees in the house stand up to be applauded, she put forth a phrase I expect we’ll be hearing a lot of: “inclusion rider.” This being, if you look it up, a contract clause that A-listers can potentially use to demand equal-opportunity hiring on the sets of their films. Go, Frances, go!

Meanwhile, among all the fabulously gowned ladies in attendance, I couldn’t help noticing that some (like Emily Blunt, Maya Rudolph, Helen Mirren, McDormand herself) were really covered up. Maybe a reminder that the touchy-feely ways of Hollywood are no longer welcome in all corners of the industry.

Published on March 06, 2018 12:25

March 2, 2018

Surprise! How Movies Hold My Attention

With the 2018 Academy Awards ceremony heading this way fast – with pundits predicting and glamorous ladies taking their #MeToo stories into fitting rooms – I’ve started mulling over my personal taste in movies. The 2017 movies I’ve most liked, I realize, are those that manage to surprise me, that take me somewhere I didn’t expect to go.

Of course surprise is a tricky business. It needs to suit the project; it can’t just be imposed on it like an M. Night Shyamalan ending. (See The Village for a particularly egregious example.) And it can’t rely on an unexpected outside force to swoop down and change everything The Greeks, needless to say, had a word for it: deus ex machina. This translates as “god from a machine,” something that was a familiar feature of classical drama. In ancient Athens, just when everyone onstage was in a state of serious crisis, a god-figure would descend from the rafters in a mechanical contraption and set things to rights. (Something of this device shows up in Shakespeare’s late play, Cymbeline, where in the modern age it’s generally played for laughs.)

Looking over the slate of this year’s Best Picture nominees, I see that my favorites are full of surprises. We know at the start that in The Shape of Water our heroine is going to fall for a sea-creature (the ad campaign makes that crystal-clear), but I hadn’t anticipated all the political intrigue surrounding the lovers. Three Billboards Outsider Ebbing, Missouri contains characters whose motives are so complex that they can absolutely shock us from moment to moment, for better or for worse. In Phantom Thread, what seems to be the story of a couturier obsessed with the need to create fine fashion takes a sharp left turn into a battle of the sexes whose outcome no one could have predicted. On a much smaller scale, Lady Bird is full of surprises, stemming both from Lucas Hedges’ character arc and the up-and-down relationship of mother and daughter.

It’s much harder to surprise when you’re dealing with history. Maybe that’s why Christopher Nolan tried so hard to tell his World War II saga of the Dunkirk evacuation in a way that is stylized, impressionistic. Only problem: it’s highly difficult to know exactly what’s going on. And so the tiny surprises built into the plot, like the identity of the main British soldier’s silent companion, just about pass us by. I must say that I found the much-admired Call Me by Your Name” woefully lacking in surprise. The gay love story is sensitively made, but there was never a moment when I didn’t know what was (oh-so-slowly) coming next.

Which brings me to Get Out, a movie that has certainly prompted a great deal of cultural conversation. I give Jordan Peele’s work high marks for that, and for dreaming up an apt metaphor for the lives of black folks in today’s supposedly liberal-minded America. Get Out has such passionate supporters within the movie industry that some critics are suggesting the film might surface as the best-picture winner at Sunday’s Oscar-fest. Here’s my problem; I do try to avoid reading reviews and hearing spoilers about films that pique my interest. But a casual radio comment by Peele himself –that Get Out can be taken as a variation on Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner—along with poster art strongly implying a horror film essentially clued me in to what was about to happen. So for me a lot of the excitement of discovery was lost. But if Get Out wins Best Picture, that will be a surprise indeed.

Published on March 02, 2018 11:51

February 27, 2018

Barton Fink in Hollywood, Where Writers Sink Slowly in the West

When actor John Mahoney passed away earlier this month at the age of 77, most commentators mentioned the popular sitcom, Frasier, in which he played Kelsey Grammer’s blue-collar dad. I have to thank my colleague, Carl Rollyson, for reminding me of Mahoney’s very different role in the Coen brothers’ outrageous 1991 Hollywood saga, Barton Fink. Carl, a prolific biographer now researching literary giant William Faulkner, loves Mahoney’s portrayal of W.P Mayhew, a celebrated novelist-turned-Hollywood-hack who (with his Southern charm and ever-present whiskey flask) is an obvious Faulkner clone.

In Barton Fink, Mayhew/ Faulkner represents the way the movie industry uses and abuses writers. With his talent squandered on scenarios for unworthy entertainments, he might as well be dead—which is why he behaves as though he already were. Fink himself (as played by John Turturro) also suggests a familiar literary type. His character reflects the career of Clifford Odets, a 1930s Broadway darling whose gritty kitchen-sink dramas (like Awake and Sing!) chronicle the triumphs and failures of the common man. Barton Fink is first seen on the evening of his greatest theatrical triumph, being feted by nightclub-goers who celebrate his contributions to the New York stage. The applause may be grand, but Fink’s agent advises that it’s time to cash in: he’s been offered a lucrative Hollywood screenwriting contract, and it behooves him to make some real money, before returning to Broadway with his wallet fattened and his dignity intact.

Except that things don’t go as planned. Barton’s time on the coast in fact comes to seem something like Dante’s descent into Hell, with horrors multiplying at every turn. The studio houses him in the seedy Hotel Earle, where the paper is peeling off the walls, a creepy Steve Buscemi seems to be the only staffer, and the motto for guests is “a day or a lifetime.” (The Hotel Earle is surely a 1940s version of Hotel California, but by no stretch of the imagination can it be called “lovely.”) Even when Fink enters swankier surroundings, like the office of the Hollywood mogul who hired him, the atmosphere remains nightmarish. His new boss and the lackeys who surround him barely let Barton get a word in edgewise, and he spots the great W.P. Mayhew vomiting in a toilet stall. Worst of all, he can’t get started on the wrestling picture he’s been assigned because his creative juices seem to have dried up for good.

I won’t get into the film’s unexpected twists and turns except to say that they somehow include his one new-found friend, a jolly insurance salesman played by John Goodman. Let’s just note that Barton Fink’s California sojourn goes from bad to worse, until he’s faced with an unspeakable tragedy. Years ago, when I saw this film in first-run, I didn’t know what to make of it. This time around, because I’ve spent so much energy pursuing the life of a writer, I’ve found myself focusing on the implications of Barton’s writer’s block. I know what it’s like to be stymied at just the moment when you need to be most brilliant. I know what it feels like when the words don’t come. One detail I’m sure I overlooked back in 1991: it is only when Barton is faced with the grimmest, the most grotesque, of real-life circumstances that he can turn his back on the world, approach his typewriter, and begin happily pounding out a story. The whole film, then, can be seen as an elaborate metaphor for the act of creation: it’s only when life is at its harshest that the imagination kicks in.

Published on February 27, 2018 13:31

February 23, 2018

Remembering “Coco”: It’s a Scary World, After All?

Little kids, I’ve discovered, like things that are scary . . . as long as they’re not TOO scary. But they’re not crazy about sitting quietly in the dark of a movie theatre for a long period of time. And they value entertainment that’s simple and straightforward. They understand about good guys and bad guys, but shades of grey are pretty much beyond them. These are some lessons I learned when I took two young family members (ages 6 and 3) on their first big movie outing, to see Pixar’s Coco.

Personally, I loved this film, the odds-on favorite to win the Oscar for best animated feature. It’s beautiful to look at, and does a splendid job of mirroring Mexican culture in a way that’s both respectful and fun. From the opening credits, spelled out in brightly-colored papel picado (paper-cut) banners, to the incorporation of Mexican Dia de los Muertos traditions, Coco is a visual treat. The music is terrific too, and the film’s message about family solidarity and respect for one’s past certainly resonates.

That being said, Norteamericanochildren six and under can be forgiven for not appreciating the charms of Coco. After all, it’s almost two hours long, which makes for a lengthy sit. And it’s complicated: not every kid can quickly grasp why the plucky young hero has to journey to the realm of the dead and (worse yet!) risk not being able to return. And Coco is—let’s face it—a wee bit scary. Hundreds of animated skeletons appear among the cast of character. Even though most of them are quite fanciful and lovable, their presence poses questions about the meaning of death that I suspect make most American kids uneasy. (Mexican culture is traditionally good at acknowledging death in ways both loving and humorous, so I’d enjoy hearing how a six-year-old steeped in that heritage would feel about the movie.)

Anyway, the two youngsters I took to see Coco have now survived their very first trip to Disneyland. The three-year-old, a girl who loves puppies and unicorns, enjoyed her dizzy ride in those whirling Alice in Wonderland teacups (every adult’s least-favorite Disney attraction), but later proclaimed that what she liked best was prancing on a white wooden horse on the King Arthur Carousel. Her big brother, newly six, was definitely in the market for scares. He survived the Haunted Mansion, then graduated to the thrills of Star Tours, the Indiana Jones ride, a Matterhorn bobsled, and the bone-rattling Wild West rollercoaster called Big Thunder Railroad. Each of these he found scary, but not too scary to be fun. I’m certain he’d go back at a moment’s notice.

Why was he put off by Coco, even though he couldn’t get enough of these thrill-rides? Well, first of all, the rides are short, so there’s precious little time to get anxious or confused. And though they may be full of physical jolts, you can’t call them mentally taxing. True, they simulate danger, but rescue always comes very quickly. Though he wouldn’t want to see Coco again, this six-year-old can be mesmerized by early Disney cartoon shorts, like one where an obvious bad guy (Pistol Pete?) is foiled by spunky hero Mickey Mouse, who deftly removes consecutive rungs of a ladder Pete is climbing. In comic shorts like this, everyone gets a bit battered, but the humor is so broad that we know there’s no harm done, and that everyone is going to live forever without anything much changing. In Coco, lives change forever—and that’s a lot to grasp when you’re sitting in the dark.

Published on February 23, 2018 10:10

February 19, 2018

“Battleship Pretension” Sets Sail at Oscar Time

Classic film enthusiasts are well acquainted with Battleship Potemkin, the thrilling 1925 silent Soviet epic in which director Sergei Eisenstein showed the Russian people rising up against their Tsarist oppressors. But do these film fans also know “Battleship Pretension”?

This latter is something totally unknown in Eisenstein’s day: a podcast. It’s been around for 13 years, regularly doling out opinions about movies. As the “Battleship Pretension” site makes clear, it offers “movie talk from two guys who think they know more than you do.” Frankly, I’m not convince they know more than I do about The Graduate. I first met Tyler Smith, one of those two self-confident film dudes, when I climbed aboard “Battleship Pretension” to talk about my new book, Seduced by Mrs. Robinson. Tyler may not have been the ultimate expert on The Graduate, but he was savvy and charming. That’s why we scheduled a second conversation to compare notes on the upcoming Oscar race. Afterward, I couldn’t resist asking Tyler about himself.

Tyler is currently a graduate student in the UCLA film school, majoring in critical studies. He’s the rare film geek who holds conservative social values, and considers himself a committed Christian. (By contrast, his co-host and longtime friend David Bax is, in Tyler’s words, “a liberal atheist.”) One thing that fascinates me about Tyler’s perspective is that – unlike a good many Christian conservatives – he has no use for censorship of any sort. Devices like Vid Angel that remove nudity and rough language from an existing film, are for him completely missing the point, and he wouldn’t dream of favoring a cleaned-up version of a Scorsese or Tarantino film, because “that stuff is the movie.” No fan of most overtly Christian movies, he points to the evolving Samuel L. Jackson character in Pulp Fiction as an unlikely but genuine Christian role model.

Each year’s Oscar season is a special time for “Battleship Pretension” and its fans. Since 2013, Tyler and David have been handing out the BP Awards, based on the votes of about 30 movie experts, including site contributors, fellow podcasters, and previous guests. The winners are announced at the end of February. Alas, there are no fancy gold statuettes, but the BP folks do generally stage an impressive ceremony that is featured on the podcast. OK, so it’s faked – but they have fun adding music, crowd noise, and celebrity photos. Tyler has loved putting these bogus events together: “I don’t know if anybody enjoyed it as much as I did.”

Most of the BP award categories are familiar ones – best supporting actor, best documentary feature – but Smith and Bax have given themselves the right to invent categories of their own. That’s why there’s an award for best stunts, as well as the unique “The Bruce McGill in The Insider Award for Best Performance Under 15 Minutes.” Past winners of this prize have included Matthew McConaughey in The Wolf of Wall Street and Channing Tatum in Hail, Caesar! But Tyler seems most jazzed about the 2016 award, which went to journeyman actor Neal Huff for his tiny but key scene as an abuse survivor who gets the ball rolling in Spotlight. Tyler loved the fact that Huff was hardly a movie star. “Battleship Pretension” contacted his publicist, and learned that Huff would be happy to tape a gracious acceptance speech.

This year’s nominees, who include Bruce Greenwood as a frantic reporter in The Post and Harriet Sansom Harris as a soused client of couturier Daniel Day-Lewis in Phantom Thread, are by no means celebrities. Let’s hope the BP Bruce McGill Award really makes someone’s day.

Published on February 19, 2018 17:29

February 16, 2018

"Dunkirk": Britain’s Band of Brothers

“Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more!” That’s the beginning of a famous speech in which Shakespeare’s Henry V urges his troops forward. It’s 1415, and the British are invading France, in a series of battles that are part of the Hundred Years’ War. Somewhat later in Shakespeare’s Henry V, the young king – who in the spirit of the times personally leads his men into battle – addresses them, manfully insisting that the odds stacked against them will only make their success more glorious. In what is always called the St. Crispin’s Day speech, Henry waxes philosophical about the long-term fame that awaits his soldiers, then rises to a glorious climax:

And Crispin Crispian shall ne'er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be rememberèd—

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers . . .

The valor of English soldiers and their leaders, as displayed in Henry V, has of course always had high appeal for English audiences. That’s why Winston Churchill, in the dark days of World War II, turned to actor/director Laurence Olivier for a film version of the play, with which to boost the morale of the English citizenry. It appeared in 1944, dedicated to “the Commandos and Airborne Troops of Great Britain, the spirit of whose ancestors it has humbly attempted to recapture.” The movie was a commercial and artistic success, winning Olivier an honorary Academy Award “for his outstanding achievement as actor, producer and director in bringing Henry V to the screen.”

Given the tensions of those times, it’s no surprise that the war as depicted in Olivier’s Henry V is picturesque and fairly bloodless. Almost 50 years later, in 1989, Kenneth Branagh was gutsy enough to film the play once again. His version (which like Olivier’s features the cream of the British acting community) is powerful and realistic, containing battlefield scenes that strongly convey the horrors of war.

I bring all this up because two films that take us back more than 75 years to another English war are in the running for the 2018 Best Picture Oscar. I confess I haven’t seen Darkest Hour, which I understand is best served by Gary Oldman’s stirring portrayal of Winston Churchill, captured at a moment when he and his strong anti-Nazi views are finally coming to be adopted by Britain’s royals and its citizenry. I did, however, see Dunkirk, which has been called an impressionistic account of the massive British evacuation of a French beach in one of World War II’s most pivotal moments. Dunkirkis a labor of love for British director Christopher Nolan, who’s best known for such science fiction and fantasy fare as The Dark Knight and Interstellar. It’s clear he feels deeply about this moment in history, when thousands of small English seafaring vessels sailed across the English Channel to rescue English soldiers. The film cuts between a pilot in the sky, the crew of a fishing boat on the water, and a representative British “Tommy” trying to leave that corpse-strewn French beach. My problem: I could never figure out quite where I was and who was at the center of the action at any given moment. (At least in my American eyes, young English actors all seem to look pretty much the same.)

Nolan has been praised for making a strikingly different sort of war film. I certainly got a sense of the enormity of the whole undertaking. But having to continuously ask “Wait, what’s going on?” is not a helpful sort of history lesson.

Published on February 16, 2018 14:09

February 13, 2018

Ice-Dancing Goes to the Movies

As happens every two years, I find the Olympic Games irresistible viewing. Even though -- technophobe that I am -- I consider the many-buttoned remote control gadgets that power my TV extraordinarily daunting, I’m currently spending my evenings glued to the tube, enjoying the scope and the sweep of winter sports. Speaking of sweeping, I can’t say I’m keen on curling, but watching snowboarding sports sure gets my blood racing. Heck, I even got excited recently during the finals of the single-man luge.

But for me the sport of sports is figure-skating. The blending of music, costumes, and dramatic emoting with first-class athleticism is for me too powerful to ignore. I’m a sucker for up-close-and-personal profiles of the skaters, and the one-two punch of Tara Lipinski and the always memorable Johnny Weir adds invaluable commentary. I learned from Weir, for instance, that in ice-dancing the woman’s role is to be the show-offy flower, while her male partner acts as her stem. Weir then went on to portray one of the teams, admiringly, as containing two flowers.

I think one of the things that intrigues me about figure-skating competitions is that they meld artful discipline with the spontaneity of live competition. When you watch a movie, you’re enjoying the result of months and years of careful planning by a whole army of participants. Yes, it’s true that the unexpected things that pop up on a movie set can have impact on a completed film, for better or for worse. Serendipity is a very real aspect of the film-making process, and smart filmmakers know how to take advantage of happy accidents. Still, when we watch a film, we’re seeing a finished product, one that has been lovingly polished and perfected before it reaches audiences. A live theatre performance can change slightly from evening to evening, depending on the mood of the audience, the health of the actors, and a host of other things. But normally theatre productions that are beyond the rehearsal stage try to conform nightly to a set of codified expectations toward which everyone has been aiming during weeks of preparation.

In figure-skating, too, there is a carefully developed plan of attack for each stage of the competition. Costumes, music, and basic choreography don’t vary from outing to outing. But this is a sport, and so anything can happen. A bobble, a recovery, a fall . . . what develops in the dynamic between pairs skaters from night to night is particularly fraught. One Canadian ice-dancer, I’m told, is super-adept at calculating point totals in her head while she’s on the ice. If one of her and her partner’s elements doesn’t go as planned, she knows how to adjust for maximum impact.

It doesn’t surprise me to sense that figure-skaters love movies. At least, they frequently turn to famous movie themes to add crowd-pleasing oomph to their programs. In the last few days, I’ve seen skaters glide to music from Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet, Memoirs of a Geisha, and “Unchained Melody,” as featured in the schmaltzy lost-love movie, Ghost. The Italian duos seem particularly adept at taking advantage of movie drama through their choice of music. One pair of Italians charmingly captured the antic spirit of Fellini by way of Nino Rota’s film scores. And an Italian ice-dancing team, skating to music from Life is Beautiful, conveyed that Holocaust film’s heartbreaking throughline by moving from romantic love to the horrors of war. All the best skaters, at least in my eyes, tell a story with their faces and bodies. And movies are often the inspiration that moves them forward.

Published on February 13, 2018 12:31

February 9, 2018

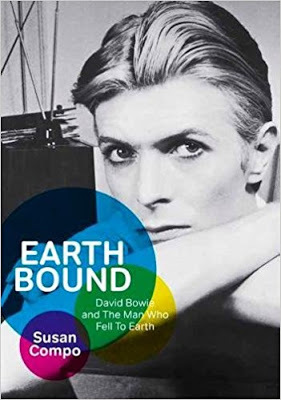

Rocket Man: On David Bowie’s Fall to Earth

Elon Musk, a canny combo of Thomas Edison and P.T. Barnum, has done it again. His SpaceX has just launched from Cape Canaveral the Falcon Heavy, the world’s most powerful operational rocket. The biggest news for science geeks is that two of the three Falcon first-stage rocket boosters were successfully returned to earth, to be reused in future. But the rest of us are probably more keen on the rocket’s payload: Musk’s own cherry-red Tesla, complete with a helmeted dummy in the driver’s seat. And, yes, the car’s audio system was said to be blasting out David Bowie’s “ Space Oddity.” Ground Control to Major Tom, indeed!

It’s a lovely coincidence that I’ve just finished reading my colleague Susan Compo’s new Earthbound: David Bowie and The Man Who Fell to Earth. Susan’s book gave me the opportunity to explore the 1976 Nicolas Roeg film that some cinéastes remember with affection, some with puzzlement, others with major annoyance. To my surprise, I learned that the film’s source novel is by Walter Tevis, far better known for a much more down-to-earth work, The Hustler. That novel, of course, inspired the award-winning 1961 classic in which Paul Newman, Jackie Gleason, and George C. Scott risk their souls in a pool hall. Though The Man Who Fell to Earth contains undeniable science fiction elements, it shares with The Hustler Tevis’s interest in men (whether earthly or from outer space) who destroy themselves through excess. The otherworldly character played by Bowie -- an alien confined to earth because he can’t find his way back to his home planet -- is in the course of the film irredeemably corrupted by the intoxicating things (and people) he encounters in his new earthly surroundings.

The British director of The Man Who Fell to Earth, Nicolas Roeg, was not without experience coaxing screen performances out of rock stars. He made his directorial debut with Performance, about a bizarre encounter between an East London gangster on the lam (James Fox) and a fading musical idol (Mick Jagger) bent on returning to his former glory. He also helmed an admired Australian film, Walkabout, and just prior to The Man Who Fell to Earth he made a major splash with the enigmatic 1973 thriller, Don’t Look Now. Starring Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland as bereaved parents mourning their drowned little girl, it is perhaps best remembered for its eerie atmosphere and frank sex scenes. (Sexual frankness, including no-holds-barred nudity, also marks the screen encounters between Bowie and earthling Candy Clark in The Man Who Fell to Earth.)

A Roeg film is always visually striking. Roeg started out as a cinematographer, working second unit on Lawrence of Arabia and taking charge of the inspired cinematography for one of Roger Corman’s very best Poe films, The Masque of the Red Death (1964). Author Susan Compo, who seems to have spoken to all the living survivors of The Man Who Fell to Earth, emphasizes the impact made on the filmmakers by the picturesque state of New Mexico, where the film was almost entirely shot. As a “right-to-work” state, New Mexico was able to welcome an almost entirely British film crew without concern about union restrictions. The state’s stark landscapes, picturesque mining towns, and general sense of isolation work brilliantly, especially the use of White Sands National Monument to simulate the arid reaches of the Bowie character’s home planet.

Still, in narrative terms the film doesn’t always make sense, partly due to Roeg’s insistence on avoiding strict chronology. Bowie, though, makes a perfect alien, with his off-camera excesses doubtlessly contributing to his otherworldly air.

Published on February 09, 2018 10:05

February 6, 2018

Super Bowl LII: Touchdowns for Movie Fans

So we’ve survived another Super Bowl Sunday, one that was more exciting than most. No, I’m not much of a football fan, though I like to look in on big national sporting events from time to time. Like most people, I generally find myself rooting for the underdog, and so the victory of the Philadelphia Eagles—following lots of twists and turns on the field—of course appealed to my sense of drama. (I especially liked the sleight of hand that had Eagles replacement quarterback Nick Foles sneaking the pigskin into the possession of a teammate, then moving down the field to catch the pass and run it into the end zone for a touchdown.)

The Eagles’ victory, the team’s first national championship since 1960, also served to remind me of one of my favorite recent movies, David O. Russell’s 2012 domestic comedy, Silver Linings Playbook. If you’ve seen the film you remember the dynamic within the Philadelphia household of a troubled young man, Pat Solitano (Bradley Cooper), who has managed to extricate himself from a mental institution and come home in search of his estranged wife. His father, Pat Sr. (played by a predictably intense Robert De Niro) rules the roost, and the focus of his energies is the local football team. This means the entire family unit must wear Eagles jerseys, participate in earnest pre-game rituals, and otherwise ensure good luck for the team. Things come to a head during an outing to Lincoln Financial Field for a home game. The famously rabid Eagles fans are out in force, well-lubricated and slathered in green paint, to cheer on their boys. Inevitably, the younger Pat gets into a fracas with some especially obnoxious (and racist) fans, and is hauled off by the cops. Which leads Pat’s father to make a bet (or “parlay”) he cannot afford to lose. Somehow it all ends on a positive note, having proven that sports fanatics and romance fanatics are not so very different after all. (Especially when there’s a cagey but complicated young woman like Jennifer Lawrence’s Tiffany around.)

A surprising number of people tune in to the Super Bowl for its commercials, and as always I was struck by the number of elaborate Hollywood-related ads that popped up on my TV screen. A new twist was the Netflix gimmick of surprising viewers with the news that a new sci fi film, The Cloverfield Paradox, would screen immediately after the game. (I didn’t watch it, but commentators seemed to agree that the industry was trying to hustle out this follow-up to the well-received Cloverfield before word got out that the film was pretty bad.) Some lively ads used familiar actors in unexpected ways – like Peter Dinklage and Morgan Freeman rapping on behalf of a new Doritos flavor, and Rebel Wilson and a Hannibal Lecter-ish Anthony Hopkins (among others) replacing the voice of Alexa. Elsewhere, Jeff Goldblum relived Jurassic Park’s scary T-Rex chase (complete with John Williams music) in a commercial for Jeep. Quite amusing was an apparent movie promo, featuring Danny McBride and Chris Hemsworth introducing what seems to be a Son of Crocodile Dundee flick. McBride’s dressed for the part of Dundee’s offspring, and he covers a lot of terrain before realizing the truth: “It’s not a movie. It’s a commercial.” Yes, this spot promoting Australian tourism makes its point about the charms of the land down under, with tongue firmly in cheek.

But I can’t say I feel good about the sonorous voice of the Reverend Martin Luther King essentially shilling for Dodge Ram trucks. Does King’s 50-year legacy deserve this?

Here's a compilation of some of the most memorable 2018 Super Bowl commercials:

Published on February 06, 2018 12:15

February 2, 2018

Willam Fox: Twentieth-Century Man

When I was growing up in West L.A., Twentieth Century-Fox Studio was just down the road from my suburban neighborhood. It always seemed incredibly glamorous to me to pass the studio gates, catching a glimpse of the make-believe inside. (For the longest time, you could see the Old New York sets used in Hello, Dolly!, an overblown musical in which many of my neighbors got hired to fill out the ranks of parade-watchers for a humongous production number.)

For all my interest in the studio, I was never clear on the Fox part of its name. Now, however, I feel like an expert. Of course, the REAL expert is Vanda Krefft, a fellow Santa Monican who’s my colleague in BIO, the Biographers International Organization. Vanda, a longtime entertainment journalist, was lucky enough to know Angela Fox Dunn, a niece of William Fox and what Vanda describes as “the keeper of the flame.” Dunn was the one who started Vanda on her quest to discover everything about William Fox—how he lived, how he worked, what he contributed. In Vanda’s telling, Fox was so important to the early development of the film industry that she calls her book The Man Who Made the Movies. That’s a big claim, given that Fox was part of the era that also included such major figures as Adolph Zukor and Louis B. Mayer. But the list of his accomplishments, as the head of the Fox Film Corporation, is remarkable. Among other achievements, he introduced the first Hollywood sex symbol, Theda Bara, gave a start to director John Ford, and produced the first Hollywood feature with an (almost) all-black cast, He also controlled a vast chain of Fox theatres, pioneered the development of foreign markets for American movies, and spearheaded the development of sound-on-film, a technique that (in preference to the sound-on-disk method used by Warner Bros. for The Jazz Singer) quickly became the industry standard. At the very first Academy Awards event, five of the twelve honors handed out were connected with such Fox films as Sunriseand Seventh Heaven.

Despite all his grand successes within the film industry (he personally received an Academy Award for producing Sunrise), Fox was not a contented man. Like the other early moguls of the film industry, he was a Jewish immigrant who had overcome poverty, anti-semitism, and family misfortune by dint of a fiercely competitive spirit. Though he adored his wife, he ruled his household with an iron fist. Among his fellow filmmakers he made lifelong enemies. The same energy that led him to high achievements also drove him to overreach, and ultimately landed him in deep financial trouble. Though he had always been a man of strong moral and religious conviction, his desperate efforts to right his sinking ship resulted in actions that were frankly dishonest. In 1942, at the age of 64, he was sentenced to prison, while other equally guilty parties apparently got off scot-free. In the meantime, his namesake companies passed into the hands of others, shysters who knew nothing about the movie business and quickly drove them into the ground. (One of many short-sighted goofs: refusing to extend the contract of the young John Wayne) . Fox Films finally survived only by linking with an upstart company, Twentieth Century Pictures.

If the story of Fox’s rise is an exhilarating one, his fall is sad indeed. But Vanda Krefft (through her diligent research and her lucid writing style) makes us care about this flawed but memorable man. Her book’s subtitle—The Meteoric Rise and Tragic Fall of William Fox—is apt indeed

Published on February 02, 2018 13:07

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers