Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 82

December 22, 2017

Glory, Hallelujah – Saluting the Men of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry

In 1989, the movie Glory brought to the nation’s attention a young actor named Denzel Washington. For playing the role of an African-American soldier fighting for the Union cause during the Civil War, he was awarded an Oscar as best supporting actor. The highly regarded film introduced to many the story of the 54thMassachusetts Volunteer Infantry, a regiment composed of free black men determined to help win the fight against slavery in the American South. Those men, and their white commander, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, are memorialized in a plaque erected in Boston Commons in 1897. Featuring a dramatic bas relief by noted sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, the plaque faces the gold-domed Massachusetts State House, a prominent and permanent reminder of men who courageously put their lives on the line to end a social evil.

Many of those men didn’t live to see the Union win the war. Glory focuses on young Colonel Shaw (a rare dramatic role for the baby-faced Matthew Broderick) molding inexperienced volunteers into a fighting unit. Washington’s character is used to show the anger of black men who are denied respect and proper uniforms because of the color of their skin. But he and the others rise to the occasion during a bold (though ultimately futile) assault on South Carolina’s Fort Wagner that leaves many dead, their bodies tosses into a ditch, black and white together, in the ultimate expression of Southern scorn.

It’s a stirring movie, one that deserves its Oscars. But it hardly covers the entire history of the 54th, nor does it go into full detail about the indignities suffered by these black men who were risking their own freedom by marching into a place where--if captured—they could legally be treated as chattel. It falls to my colleague Ray Anthony Shepard, a writer and educator whose grandfather was born a slave, to give us the whole chronicle of this courageous group of soldiers. His new book is called Now or Never!: 54th Massachusetts Infantry’s War to End Slavery. It’s intended for classroom use, but all of us can learn a great deal in its pages.

Shepard’s extensively researched account makes particular use of the writings of two volunteers, George E. Stephens and James Henry Gooding. Through their letters and their newspaper accounts from the front lines, both give the perspective of free black men gambling everything to free their enslaved brethren. One didn’t survive the war; the other grew increasingly bitter as he was repeatedly denied a hard-earned promotion to officer’s ranks because of his “African ancestry.” It was not until 1891, well after his death, that he was granted the lieutenant’s stripes he had long ago earned. The Union side, it seems, was by no means color-blind. Colonel Shaw himself started as no fan of the idea of emancipation, though he was soon pleasantly surprised by the intelligence of the black soldiers under his command. Higher-ups in the Union army played cruel tricks on men who’d been told their pay would be equal to that of white soldiers. When their expected $13 pay packets were reduced to $10, with an additional $3 charged toward their uniforms, there was a near-mutiny. So concerned were some in the War Office that black men were being trained to use rifles that there was talk of allowing them to face the enemy with only long pikes in their hands. But their courage in battle quickly put an end to that idea.

Shepard’s account is disturbing but fascinating. It shows us how much more there is to learn—and maybe there’s a movie in that?

Published on December 22, 2017 10:00

December 19, 2017

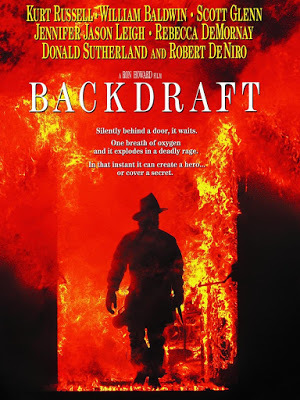

Backdraft: Fighting Fire with Fire

As wildfires continue to rage across Southern California, scorching thousands of acres and putting homes (and lives) at risk, my thoughts return to a 1991 film that treats fire with the respect it deserves.

Backdraft began as a concept by screenwriter Gregory Widen. Before entering film school, Widen had spent three years as a Southern California fireman. In the line of duty, he saw a buddy blown across a six-lane highway and impaled on a metal post by the deadly explosion known as a backdraft. Widen’s goal was to write a tense thriller built around the working lives of firefighters and their heroic dance with danger.

When Ron Howard came aboard as director, he chose to play up the complex rivalry between two brothers from a Chicago firefighting family. Stephen (Kurt Russell) and younger brother Brian (William Baldwin) are both still reeling from the death of their fireman father. Stephen has grown up with a personal vendetta against fire: he’s the first to rush into any precarious situation, and he refuses to wear a gas mask. Brian, having tried in vain to stay away from the family profession, is both enthralled and intimidated by his elder brother’s brash heroics. He sees in Stephen’s crumbling marriage a reminder of the price some firemen pay for their obsessive insistence on grabbing every fire by the throat.

Where Backdraft works best is in its depiction of fire itself. Howard discovered that firefighters see fire as a living creature with a will of its own, one that “has its own thought patterns, it behaves in odd ways, it slithers and it laughs and hisses and giggles, and we’re trying to create a sense of that in the fire scenes.” Through state-of-the-art visual effects by Industrial Light and Magic, but also through the gutsy willingness of cast and crew to move in close to actual flames, Backdraft conveys the elemental power of fire in a way no previous film had ever done.

The Backdraft team chose to focus on the Chicago Fire Department because of its reputation as the most stubbornly macho in the country. Chicago firemen traditionally disdain those who stay on the perimeter of a burning building, shooting water from hoses in what they call a “surround and drown.” Their own preferred method is to rush inside and tackle the blaze, thus exposing themselves to the possibility of great personal harm. In shooting Backdraft, Howard and his crew followed much the same pattern. Though camera operators were encased in fire-suits and though the leaps of the flames were carefully choreographed, danger was always present. By the time shooting ended, there had been more than one close call. An actual fireman playing a minor role had his eyebrows singed off, his first accident after twelve years on the force. The moment production wrapped, Howard nearly wept with relief. He insisted that if movies, like Olympics events, were judged on a degree-of-difficulty scale, “this would be a nine and a half. I was constantly riding this line, trying to maximize the excitement and be safe at the same time.” No wonder he’s never considered a sequel.

Since Backdraft’s release, Howard has been treated as a hero by firefighters throughout the nation. His heightened awareness of the hazards faced by firemen has led him to appear on Capitol Hill, lobbying for federal funds to improve their training. But his serious interest in the work of firefighters never kept him from appreciating Universal Studio’s now-shuttered Backdraft theme-park attraction, in which visitors experienced an actual chemical blaze. Said Howard, appreciatively, “You can feel the heat on that ride.”

Dedicated to the many brave fire fighters now on the front lines in California and elsewhere

Published on December 19, 2017 10:30

December 15, 2017

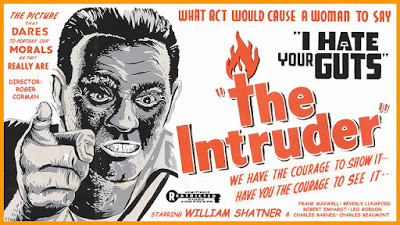

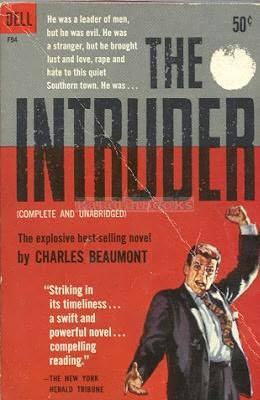

A Closer Look at "The Intruder "

Every true Roger Corman fan knows the story of The Intruder: how in 1961, when the Civil Rights movement was just starting to hit its stride, Roger discovered Charles Beaumont’s gutsy 1959 novel and decided to adapt it for the screen. Written in 1958, it was a fictional account of a white rabble-rouser who turns up in a small Southern town to fan the smoldering flames of racial hatred. Hollywood showed some interest in filming Beaumont’s work, then decided it was too controversial for its era. When Corman and his brother Gene became involved, they thought they’d be making their movie for United Artists. Tony Randall was in negotiations to play the leading role, and the budget was projected to be $500,000.

Soon, however, it became apparent that the Corman brothers were on their own. Most of the production costs (in the neighborhood of $70,000) came out of their own pockets. For reasons of authenticity as well as cost control, the feature was shot entirely on location, primarily in rural Missouri, near the Arkansas border. William Shatner, a young Canadian stage actor still lightyears away from becoming Captain Kirk, was signed to play the charismatic demagogue, Adam Cramer. Getting other actors to commit to the project wasn’t easy. Author Beaumont, who adapted his own novel for the screen, stepped in without salary to play the courageous school teacher, and many parts (including that of the black high school student who sparks the film’s crisis) were taken by non-professionals living in the region.

By shooting this story in towns where it could have happened, Corman and crew were courting real danger. For three weeks they dodged sheriffs, eluded threats of violence, and sidestepped accusations that they were Communists. Some of the script’s most incendiary moments remained unfilmed. Still, reviews were mostly respectful. But the audience stayed away, and Corman—losing money on a picture for the first time in his career—returned to making horror flicks. Still, he has always remained justifiably proud of his one big foray into socially conscious cinema.

Just recently I was sent by Christopher Beaumont, the late author’s son,a new edition of the source novel. It reminded me what an excellent writer Charles Beaumont was, before he succumbed to a cruel disease at age 38. His novel uses verbal mastery to paint a vivid and convincing picture of the dog days of summer in a sleepy Southern town: “Summer had a magic to it, a magic way of frying the nerve ends, boiling the blood, drying the brain. . . . It was the season of mischief, the season of slow movements and sudden explosions, the season of violence.” (Corman’s black-and-white filming doesn’t fully capture this sense of oppressive Southern heat, though 1967’s Oscar-winner In the Heat of the Night comes close.)

Beaumont also succeeds in peopling his town with a raft of complex characters. Most important, he makes us understand where Adam Cramer is coming from, and why he—an outsider and a Yankee—feels the need to stir up racial trouble in the Deep South. This, alas, is where The Intruder feels most prescient. It warns that a single ambitious man can use a culture-wars issue like forced school integration to bend a community to his will. Here’s Adam’s formula for success: “Play on their ignorance, underline and reflect their prejudices; make them afraid.” This stealthy march toward fascism is, in Beaumont’s eyes, easily accomplished: without concerned citizens and a free press to stop you in your tracks, you can “become a dictator before the people’s eyes without anyone seeing it happen.”

Big thanks to Chris Beaumont for supplying me with a handsome new edition of his father’s novel

A desperate Roger Corman attempt to drum up audiences for his film

A desperate Roger Corman attempt to drum up audiences for his film The novel's original cover

The novel's original cover

Published on December 15, 2017 12:09

December 12, 2017

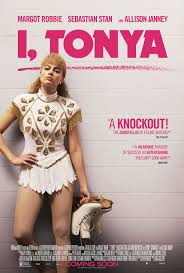

Tonya Harding Rolls with the Punches

I, Tonya, which explores the public perception of this country’s most notorious ice queen, could not be timelier. These days—when image is everything and a future president once bragged that his great popularity would allow him to get away with murder—the story of figure-skater Tonya Harding seems right on the money in terms of the way we Americans look at crime. What happened backstage at a Detroit ice arena two decades ago definitely has legs, and this new film brought it all flashing back to me.

I’m a fan of competitive figure-skating, especially when the Winter Olympics are drawing near. So I absolutely remember the build-up to the 1994 U.S. Figure Skating Championships, which would determine the American skaters who’d vie for Olympic gold. The ladies’ event pitted Nancy Kerrigan, a slender, fragile-looking young lady from Massachusetts who was known for her grace on the ice against Tonya Harding, a solidly-built wild-child from Portland, Oregon, renowned for her athleticism. (She was the first American female to successfully land a triple-axel in competition.) Unfortunately for Tonya, who came from a working-class background, she never fit neatly into the genteel world of ladies’ figure-skating. In an arena where it helped to seem delicate and demure, she was a powerhouse on the ice. The product of two bad marriages (her mother’s and her own), she projected an image that was tough as nails, and she had the mouth (as well as the swagger) to turn judges against her.

On that infamous evening in Detroit, Nancy Kerrigan—following a practice session—was felled in an arena hallway by an assailant wielding a metal police baton. The assault badly bruised her leg, but it could have been far worse: her kneecap was the apparent target. The news reports that quickly flashed across the nation featured Kerrigan on the ground, writhing in pain, moaning “Why me?” It didn’t take long to locate the “masterminds” behind the senseless attack: Tonya Harding’s ex-husband and his goofball friend, who was Tonya’s self-anointed body-guard. The question of Harding’s own culpability has never been settled. She has always denied that she knew of the plan, but her innocence is far from certain. In any case, she (so obviously a bad-girl), was quickly declared guilty in the court of public opinion. Today there are those still convinced that SHE was the baton-wielder, striking down her toughest competition for a spot on the Olympic team. The press happily went along with this scenario, which pitted a trailer-trash vixen against a sweet little swan, (Nancy’s big number used music from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake.)

I, Tonya doesn’t exactly set this misperception to rights. Instead, it does something far more interesting, using a documentary format to conduct on-camera interviews with Tonya (Margot Robbie) and the dominant figures in her life, including abusive ex-husband Jeff Gillooly (Sebastian Stan), and her gorgon of a mother, LaVona (the unforgettable Allison Janney). Those interviews give us pieces of the story, but also show us what a rare thing it is to be able to nail down the facts of a notorious public event. Characters contradict one another, and talk back to the camera. At one striking moment Tonya even blames us in the audience for the prurient attention that encourages reporters to run with half-truths.

The real Tonya Harding was interviewed extensively for this film. In Robbie’s spirited portrayal, she comes across as an often infuriating but ultimately sad figure. Still, she’s a survivor. What did she do after being banned for life from the figure-skating world? In 2003, she debuted as a professional boxer. Ouch!

Published on December 12, 2017 13:25

December 8, 2017

Charles Taylor Goes to the Drive-In

Back in the days when I read film criticism for breakfast, I fell in love with the writing of Pauline Kael in The New Yorker.. Kael’s great gift was her ability to make you eager to see a film you knew in advance you wouldn’t like. It was because of Pauline Kael that I actually paid to watch the 1973 remake of King Kong, the one with Jeff Bridges and Jessica Lange. I’ve never been much of a fan of movies starring giant SFX apes. But Kael made the movie sound so interesting—and so profound a commentary on the era’s culture—that I couldn’t let it pass me by.

That same talent animates Charles Taylor, himself a Pauline Kael acolyte. Taylor, a New York intellectual who can quote the poetry of William Butler Yeats in passing, is quite capable of writing serious appreciations of Golden Age directors like Preston Sturges, Howard Hawks, and John Ford. And yet he has chosen to focus in his first book on the allure and the impact of genre movies, those fast-and-cheap cinematic efforts that rely on such box office staples as sex and violence to help draw a vivid picture of the times in which they are made. Taylor’s new work is called Opening Wednesday at a Theater or Drive-In Near You: The Shadow Cinema of the American 70’s. As a Roger Corman alumna in good standing, I could not resist this enticing appreciation of the sort of down and dirty flicks we churned out in 1974 in great numbers.

Admittedly, Taylor doesn’t seem to have the highest regard for the movies we made at Corman’s New World Pictures. Candy Stripe Nurses, TNT Jackson, and Death Race 2000 (all of which played a major role in my working life) are clearly not in his pantheon. But he has high respect for the accomplishments of Corman graduates like Monte Hellman (Two-Lane Blacktop) and Jonathan Demme (Citizen Band). And one of his most vivid chapters is an appreciative look at Corman protégé Pam Grier. After first making her mark as a tough, sexy woman warrior in New World’s The Big Doll House, The Big Bird Cage, and The Arena, Grier went on to star in such blaxploitation revenge dramas as Coffy and Foxy Brown. Sizing up Grier’s career, Taylor smartly acknowledges the role played by race in hampering her advancement: “One of the paradoxes of the movies is that you can be a star—by which I mean you can display all the charisma and commanding presence and style that marks you as born to be in front of a camera –and never break out of second-rate movies or get the roles that you deserve. . . . For all the pleasure there is in watching Pam Grier, despite her having become an icon revered in hip-hop culture—despite Quentin Tarantino, who with a fan’s devotion and a director’s masterstroke gave her the starring role in Jackie Brown—there’s no escaping that she never had the career she should have. Pam Grier was a star, but only to black Americans.”

Taylor mourns the state of movies today, the fact that DVD and cable have largely robbed us of “the possibility of shared discovery that has always been at the heart of moviegoing. Moviegoing is rarely as thrilling as when audiences feel they are collectively hearing truths no one has bothered to say publicly.” That’s part of the reason, he feels, that today’s hits seem so ephemeral.

Unlike a movie he’s made me dying to see: Sam Peckinpah’s Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia.

Published on December 08, 2017 13:32

December 5, 2017

Lady Bird, Lady Bird, Fly Away From Home

No, I’ve never lived in Sacramento, nor did I attend a Roman Catholic girls’ high school. (As if!) Still, Lady Bird scored with me as it’s been scoring with audiences everywhere because it contains the ring of truth. Greta Gerwig’s directorial debut is not fancy filmmaking, technically speaking. But it’s wonderfully secure in its handling of actors who are far more three-dimensional than the comic-book cut-outs we’re using to seeing at the movies.

Gerwig is a rising young actress, known for her appearance in 20th Century Women and the title role in Frances Ha (for which she co-wrote the screenplay with then-beau Noah Baumbach). Though she grew up in Sacramento, California and attended the all-girl St. Francis High School, she has insisted that the rambunctious, rebellious lead character in Lady Bird is not a portrait of the artist as a young woman. Still, it’s clear from her conversation with host Peter Sagal on my favorite radio quiz show, Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me, that the line between Lady Bird and the seventeen-year-old Greta is a blurry one. Gerwig describes her younger self as much more mild-mannered and well-behaved than Lady Bird. In the course of a fight with her mother, Greta certainly never jumped out of a moving car. (In her case, the car was only idling.) It’s true, though, that she and her mom waged epic battles, which ended as quickly as they started, because beneath it all they felt an intense love for one another.

Actors who move into the director’s chair tend to be especially adept at gathering terrific casts. Gerwig has certainly done that here. Her leading lady is Saoirse Ronan, the gifted young (23-year-old) Irish actress who nabbed a supporting actress Oscar nomination (for Atonement) when she was just thirteen. Adept at accents and at complex characterizations, Ronan finally played an Irish lass not far removed from her own age and personality type in 2015’s Brooklyn, for which she was deservedly named a best actress nominee. Oscar will probably single her out again this year for her unforgettable high-schooler in Lady Bird. Before I saw the film, I assumed she’d be playing the school rebel, someone abrasive and angry, a regular flame-thrower. Well, yes, but Christine McPherson (who insists Lady Bird is her given name, because she gave it to herself) can also be soft, vulnerable, and unexpectedly sweet.

Lady Bird is attracted to two very different high school boys, played by rising stars Lucas Hedges (Manchester by the Sea) and Timothée Chalamet (Call Me By Your Name),with unpredictable results. She has a chunky best friend who gets good grades; then there’s the richer, cooler girl she aspires to be. She adores her warm-hearted sad sack of a father, played by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Tracy Letts. But her most complex emotions are directed toward her mother, Marion, played by Broadway actress Laurie Metcalf in a performance that pundits are saying is ripe for Oscar love. Marion is very much at the heart of the McPherson family: she’s hard-working, practical, and a great friend to those in need. As keeper of the family’s finances, she’s tight with a dollar, so of course she has no use for Lady Bird’s dream of getting out of Sacramento (which she deems the boring mid-west of California) and heading for a pricey east coast college. Nor do the two agree about clothes or about pretty much anything else. Still, the love is there, bubbling up when least expected.

Lady Bird is a small movie that makes the most of what it’s got. To which I say Hallelujah, and Amen.

Published on December 05, 2017 14:33

December 1, 2017

Harry and Meghan: Going Beyond the Disney Princess

The happiest news of recent weeks is surely the engagement of Britain’s Prince Harry and commoner Meghan Markle. Markle is surely not the most obvious choice to be a royal princess bride. In fact, some have compared her to the infamous Wallis Simpson, whose love affair with King Edward VIII led to his abdicating his throne in order to marry the woman he loved. Back in 1936, Mrs. Simpson was widely considered unsuitable to be an English king’s consort because not only was she an American but she’d also had two failed marriages prior to her romance with the man she called David Windsor. (Her portrayal in The King’s Speech as a haughty glamour girl is hardly a sympathetic one. Which is understandable when you realize that in the post-abdication years the couple, from their hideaway in the south of France, apparently became Adolf Hitler enthusiasts.)

Like Mrs. Simpson, Meghan Markle is American-born. In fact, she’s a native Angeleno with no apparent high society ties. Yes, she’s had a previous spouse, though only one. (These days, being divorced is hardly a rarity.) She’s an actress by trade, and an independent woman by inclination. Most remarkable of all, she’s the produce of a mixed-race marriage, with an African-American mother and an Anglo dad. The fact that the Queen of England has welcomed the match is a sign of a real shift among British nobility, though this hasn’t stopped British tabloids from posting nasty stories about Markle’s “ghetto” roots.

Naturally most of the public, both here and in England, has been swept away by the Cinderella story of a commoner marrying a prince. The pending nuptials seem especially exciting in an era wherein every little girl seems to want to grow up to be a Disney princess. (Even William and Kate’s small daughter, Charlotte, is said to yearn to be a princess someday: she’s totally oblivious to the fact that in reality she IS a princess.)

Disney’s animated films these days lean strongly toward young female characters who are, or become, princesses. Take, for instance, Anna and Elsa as ice-princess sisters in the Disney mega-hit of 2013, Frozen. But Disney had jumped on the princess bandwagon as early as 2001, with the release of The Princess Diaries, a film version of Meg Cabot’s popular series of YA novels. The Princess Diaries, which marked the screen debut of the adorable Anne Hathaway, can be considered wish-fulfillment for every awkward young girl. Hathaway’s character, Mia, is a gawky and not-very-popular American teenager, until she suddenly stumbles upon the family secret: she’s actually the crown princess of the (purely fictitious) European kingdom of Genovia. Which means, of course, tiaras and balls and all things royal.

Little girls fantasize that being a princess means pretty dresses and romantic escapades galore. I can’t help remembering one of my favorite films, which has an entirely different message. In 1953’s Roman Holiday, Audrey Hepburn is Princess Ann, who—when traveling outside of her own country—is stuck listening to dreary welcome speeches and making diplomatic small talk at formal receptions. The film’s focus is on her escape into the streets of Rome, where she gets a trendy haircut, rides on the back of a motorcycle, participates in a street brawl, and otherwise has a commoner’s kind of fun. She can’t dodge her royal duties forever, but we know that in the interim she’s learned something about being an independent young woman.

Here’s hoping that Meghan Markle, the American commoner on the brink of becoming British royalty, never feels the need for an escape route.

Published on December 01, 2017 10:00

November 28, 2017

Remembering Rance Howard, or Father Really Does Know Best

Rance played Bruce Dern's brother in one of his last films

Rance played Bruce Dern's brother in one of his last filmsFor me Thanksgiving weekend ended on a sad note, with the news that Rance Howard had passed away at the age of 89. Rance was not a household name, like his famous son, Ron. But anyone acquainted with the Howards is well aware that Ron’s steadiness and common sense are part of the family legacy. Jean Howard once said of the grown-up Ron, “He’s the most determined person I ever met in my life. I think he gets this from his dad.”

Rance Howard started out in an unlikely place for an actor, and with an unlikely name. He was a Oklahoma farm boy, born Harold Engle Beckenholdt, who discovered the magic of cinema when merchants screened free movies to lure the country folk to town on Saturday nights. He first met his future wife, Jean Speegle, when they acted together in productions at the University of Oklahoma. Later they toured in a bus-and-truck theatre troupe, starring in child-friendly productions of Cinderella and Snow White. Sometimes the troupe was short on dwarves, so the tall, lanky Rance would get on his knees to fill in.

Later, after son Ronny entered their lives, Rance and Jean moved to New York City to further their careers. At one audition, Rance discovered that a small boy was needed for a featured role. Because he and his four-year-old son enjoyed performing comic scenes from Broadway hits, it seemed appropriate to bring Ronny in to meet director Anatole Litvak. That’s how Ronny Howard got his first screen credit: the movie was The Journey, starring Yul Brynner and Deborah Kerr.

When the family moved to California, Rance nabbed small parts in a number of films and TV dramas, but it was Ronny who was the breakout star. The nation fell in love with the cute redhead who played Opie Taylor on The Andy Griffith Show. Rance was a familiar presence on the set, playing a few roles and even writing an episode called “The Ball Game” that became his son’s very favorite. Even more important, he was there to supervise Ronny, ensuring that his son was always a consummate professional and never a spoiled brat. When I was researching Ron Howard: From Mayberry to the Moon . . . and Beyond, I spoke to a number of Hollywood performers—Shirley Jones for one—who remembered Rance gently coaching from the sidelines, helping Ronny handle emotional scenes but never usurping the director’s prerogative.

When Ronny Howard the actor evolved into Ron Howard the director, the family unit remained close. Ron’s first directing gig came out of a deal he’d made with B-movie legend Roger Corman. Ron, then at the height of his acting fame on Happy Days, was being sought to play the lead in a teen car-crash comedy called Eat My Dust. Eager to move into directing, he accepted the role with the understanding that if the film did well he’d have the chance to write and direct a movie on a subject of Corman’s choosing. It turned out Roger wanted more of the same. And so Ron and his father were soon hammering out Grand Theft Auto, about a young couple who steal a Rolls Royce and head out to Las Vegas to get married, with a good many people in hot pursuit.

I was fascinated to learn, when I questioned Corman story editor Frances Doel, how well the two Howards functioned as a team. It’s not many a 23-year-old, on the brink of a career breakthrough, who can work comfortably with his dad. But Rance Howard was clearly a very special man.

Published on November 28, 2017 13:24

November 24, 2017

Illeana Douglas, or “Don’t Cry for Me, Dennis Hopper”

So Charles Manson, who sent shivers up our spines back in 1969, is dead. Which hardly brings his victims back to life. And, around the world, bad things are happening to good people. Politics? Don’t get me started. But this is Thanksgiving weekend, so who am I to dwell on the negative?

Instead, I’m giving thanks for a wonderful woman named Illeana Douglas. You may have caught her in movies like Goodfellas, Cape Fear, and To Die For. You may have seen her rare leading role in Allison Anders’ music industry indie, Grace of My Heart. If you love old movies, you’ve surely watched her grandfather, Melvyn Douglas, in the course of his great career. Illeana idolized her father’s father, and it was partly under his spell that she chose to spend her life on movie sets.

But her own father it upon a far different life for himself. And movies were entirely to blame. It was with her father in mind that Illeana chose the title for her 2015 memoir: I Blame Dennis Hopper. You see, back in 1969, Illeana’s parents went to see Easy Rider, and nothing was ever the same thereafter: “After my father saw Dennis Hopper in Easy Rider, he started, well, acting like Dennis Hopper in Easy Rider.” This meant quitting his 9-to-5 job, growing a floppy mustache, and endlessly playing “Born to Be Wild.” It also meant abandoning the family’s nice Colonial house in suburban Connecticut in order to start his own commune, a place full of dope-smoking freeloaders who had grown Dennis Hopper mustaches of their own. And it meant an all-purpose stoner response to every situation: “This is what it’s all about, man.” Illeana’s account of the break-up of her parents’ marriage is both heart-breaking and hilarious. It ends with the author, on a movie-set, meeting the real Dennis Hopper and discovering he was probably not to blame, after all. Because the life-lessons she’d learned in the course of her eccentric upbringing were pretty cool indeed.

Other chapters in I Blame Dennis Hopper reflect the fact that Illeana is the ultimate movie fan, someone who views the world in terms of the way that movies (and movie stars) have shaped her outlook. I’m not sure I agree with her theory that “all movie lovers have some sort of void or sadness in them that movies fill.” But she certainly makes a good case for the power that screen stars have over those of us who sit in the audience. Here’s her comment on Liza Minnelli: “We look up to movie stars. We believe in them, because they are larger than life, and it makes us believe in ourselves when no one else does.”

And here’s her down-and-dirty encapsulation of her own existence: “My life is like a movie. At first it was a Busby Berkeley musical with everybody happy and dancing, and then it was like a French film that I didn’t understand, but I looked really good, and now it’s like a seventies disaster movie where I’m screaming, but no one can hear me.”

Speaking of screaming, that’s one of Illeana’s special talents. A blood-curdling screech brought her to the attention of Martin Scorsese, who used it to good advantage in The Last Temptation of Christ and became her main man for a number of years. I don’t know about her love life now, but I know she keeps busy as an actress, writer, producer, and director. And then there’s her podcast, on which I was lucky enough to be a guest. It’s called, inevitably, “I Blame Dennis Hopper.”

Published on November 24, 2017 09:28

November 21, 2017

Running on Empty with Two-Lane Blacktop

Years ago, when I was interviewing for a job with B-movie mogul Roger Corman, he insisted I read and prepare to discuss with him Siegfried Kracauer’s Theory of Film. As his subtitle, The Redemption of Physical Reality, suggests, Kracauer saw film as fundamentally a visual medium, one that captures photographically the way the world looks and moves. Of course I felt obliged to read this ponderous tome from cover to cover, and waited for my chance to have an in-depth discussion about its merits. But, though I got the job, Roger never mentioned Kracauer again.

I brought up this little story when I interviewed one of Roger’s many famous alums, the cult filmmaker Monte Hellman. Monte, who had been fairly detached throughout most of our conversation, suddenly sat up and took notice. He explained that throughout his career he had spent a good deal of time talking to interviewers like me, and that it was rare for him to learn anything new. But I had managed to surprise him. He’d had no idea that Roger was interested in Kracauer’s Theory of Film, but said: “That happens to be one of my Bibles, so I’m very amazed at that.”

My own hunch is that Roger, who loves being au courant about intellectual matters,, had picked up on Kracauer through Monte himself. Back in the early days, while preparing to make one of Roger’s cheapie films, the two had together driven Highway One from Carmel to San Francisco. A lot of their talk involved their feelings about Nietzsche, but I suspect Kracauer raised his head as well.

In any case, I thought about Kracauer recently while watching Monte’s most well-known film, 1971’s Two-Lane Blacktop. As Charles Taylor explains in his fascinating chronicle of movies in the Seventies, OpeningWednesday at a Theater or Drive-In Near You, Two-Lane Blacktop was not an indie but a genuine studio release, bankrolled by Universal Pictures as its response to the success of Easy Rider. Like Easy Rider it’s about young men in motion, traveling aimlessly across the American landscape in search of . . . whatever. Instead of motorcyles, the taciturn characters known only as The Driver and The Mechanic roar through the Southwest in a souped-up ’55 Chevy sedan. There’s also a young woman, equally adrift, who’ll hook up with any male who happens by. Then there’s G.T.O., a middle-aged would-be hipster in a spiffy canary-yellow muscle car. He’s as talkative as the others are silent, but his self-aggrandizing stories don’t usually convey the ring of truth. A challenge is issued, and the race is on. They’ve wagered their cars’ pink slips, so the outcome ought to be important.

Except it’s not. Monte’s original cut ran 3 ½ hours. Contractually he was obliged to get his film under 120 minutes, and so he did. But what he cut was surprising. Gone were most of the film’s racing footage and the drama of combat behind the wheel. Monte retained instead the dingy diners, the small town gas pumps, the tedium of going nowhere for no particular reason. The cast was unusual too, featuring musicians James Taylor and the Beachboys’ Dennis Wilson along with another acting novice, Laurie Bird. Only the blabby G.T.O. was played by an experienced actor, the marvelously manic Warren Oates. The result is less a story than a haunting mood piece.

Here’s a viewer comment I found on IMDB: “This is either the best film I've ever seen, or just an interesting exercise in film-making that is ultimately of little value. The problem is that I can't decide which.” But Kracauer would have been proud.

Published on November 21, 2017 08:00

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers