Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 83

November 17, 2017

Matthew Bourne Runs Away with The Red Shoes

The Red Shoes started out as a story by Hans Christian Andersen, dating back to 1845. The dour Danish writer—whose fairytales were far grimmer than those of the brothers Grimm—conjured up a pair of demonic dancing slippers that destroy a young girl’s life: she can’t remove them, even after she’s chopped off her own feet. I’m not a fan of the Andersen story, but I can’t help loving the 1948 English film from the powerhouse team of Emeric Pressburger (love that name!) and Michael Powell.

This cinematic Red Shoes becomes the tragic story of a ravishingly beautiful ballerina -- flame-haired Moira Shearer -- torn between true love (in the person of a shy young composer) and artistic ambition (personified by the impresario of a prestigious dance company). The film, released not long after the dark days of World War II, was an opulent Technicolor fantasia, full of bravura dancing and big gaudy emotions. It adapts the gist of Andersen’s story into a ballet within the movie, the star vehicle that ensures the ballerina’s fame and undermines her human existence. One of its many charms is the casting of such bona fide ballet maestros as Robert Helpmann and Léonide Massine in featured roles. But the central focus of The Red Shoes is Shearer as Victoria Page, desperately dancing for her life. Many little girls who were enrolled in dancing classes saw the film in the 1950s, and they’ve never gotten over its impact.

A 1993 attempt to turn The Red Shoes into a Broadway musical gathered such stellar behind-the-scenes talents as Jule Styne (composer), Marsha Norman (lyricist), Stanley Donen (director), and the dance world’s Lar Lubovitch (choreographer). Even Flying by Foy, the outfit that has helped generations of Peter Pans soar aloft, got involved. But it was all for naught: the show lasted for a total of five performances.

Now along comes Matthew Bourne to usher The Red Shoes into a new era. (It had an award-winning run in London, and I saw it during its U.S. premiere, at L.A.’s Ahmanson Theatre. By now it’s doubtless dancing its way to New York.) Bourne is a choreographer, but one who hails from an unconventional background. Totally without traditional ballet training, he became obsessed with dance as a young boy enamored with MGM musicals. His inspiration was Fred Astaire, not Rudolf Nureyev. He formed a dance company while still in his teens, but didn’t actually study dance (at the Laban Centre for Movement and Dance) until the ripe old age of 22. His breakthrough was an astonishing 1995 production of Swan Lake that featured male swans. Many of the full-length ballets he’s done since have set familiar tales like Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, and Carmen in detailed social settings. (His version of Cinderella, for instance, takes place during the life-or-death London blitz of World War II.) Some of his inspiration still comes from the movies. One of my favorite Matthew Bourne ballets is derived from Tim Burton’s film, Edward Scissorhands.

As someone who grew up immersed in modern dance, not ballet, I love the fact that Matthew Bourne doesn’t force every woman’s feet into foot-crippling toe shoes. His dancers are beautifully trained, but they can perform in soft slippers, in high heels, or in bare feet. When his ladies go en pointe, it’s for a dramatic reason. And I also love his feel for the all-encompassing world of movies. His works are not just about purity of movement but also about characterization and stage design. No surprise: the name of his company is Adventures in Motion Pictures.

Published on November 17, 2017 10:00

November 14, 2017

Steve Buscemi: A Guy Without a Ghost of a Chance

It all started when I was booked to appear on Illeana Douglas’s podcast, I Blame Dennis Hopper (about which more later). Illeana is both an actress in films and a lover of films, and her enthusiasm has led me to check out several movies that feature either her or her beloved grandfather Melvyn Douglas (who won his first Best Supporting Actor Oscar for 1963’s Hud and his second for 1979’s Being There). That’s how I came to watch Terry Zwigoff’s Ghost World (2001), in which Illeana plays an ultra-sincere but naïve art teacher who interacts with the film’s heroine in an important way.

Ghost World, based on the comic book by Daniel Clowes, is the story of two brand-new high school graduates, Enid (Thora Birch) and Rebecca (Scarlett Johansson). Awkward social outcasts, they strike a rebellious pose, priding themselves on being too good for their classmates as well as the residents of their non-descript suburb. (Note to Angelenos: the bleaky contemporary streets can be found in Santa Clarita.) For a while the film goes on in this vein, showing the two girls making vague attempts to find work and an apartment to share, while unleashing catty remarks on anyone who comes within earshot. But things start to change when, just for the hell of it, they play a dirty trick on a lovelorn man who’s had the bad sense to put a personal ad in the local paper.

That ad is placed by an obsessive record-collector named Seymour, and he’s played by Steve Buscemi, an actor who is always worth watching. Gradually Enid comes to know Seymour. Though he’s dweebishly unattractive and acutely conscious of his own failings, he has a passion for early jazz that’s contagious. While Rebecca works at her dreary job and obsesses about the amenities of her future apartment, Enid is soaking up new aesthetic ideas. These contribute to the work she does in the summer school art class she must take in order to complete her graduation requirements. She’s got real talent, but her unorthodox approach is going to set her up for eventual failure.

Meanwhile, she’s coaching poor Seymour in finding love, only to become acutely jealous when he seems to have succeeded. The relationship of these two—the rebellious young woman and the morose, anxious middle-aged man—plays out in surprising ways, and ultimately becomes the film’s heart.

Birch, so memorable as Kevin Spacey’s disillusioned daughter in 1999’s American Beauty, is a memorable presence. But for me the movie belongs to Steve Buscemi, who seems as though he can’t help attracting odd and remarkable roles. In many of them, he dies in grotesque ways—see him ending up in the woodchipper in the Coen Brothers’ Fargo. Sometimes he gets away with murder (check out his role as Mr. Pink in Reservoir Dogs and his recent TV portrayal of a corrupt politician in Boardwalk Empire), but whether he’s fundamentally cowardly or fundamentally brutal he generally comes across as a nogoodnik. That’s why I cherish his rare lovable role, like that of the nebbishy Donny, sidekick to John Goodman’s Walter, in The Big Lebowski. As Seymour in Ghost World, Buscemi is capable of bursts of destructive rage. But for the most part he’s a good guy who knows he’s a loser. He badly wants love, and is capable of great tenderness when he thinks he’s found it. But things never quite seem to resolve in his favor. Having learned from his example, Enid may eventually finds her way out in the the larger world. But alas poor Seymour—he remains stuck in place.

For Illeana Douglas, who introduced me to Ghost World.

Published on November 14, 2017 10:58

November 10, 2017

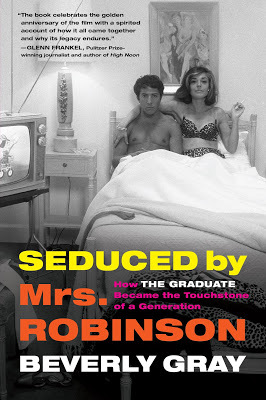

In Bed with Mrs. Robinson – My Fifteen Minutes of Fame

Andy Warhol once predicted that each of us will be famous for fifteen minutes. If so, I’ve had more than my share of fame this week. On Tuesday, November 7, my Seduced by Mrs. Robinson: How The Graduate Became the Touchstone of a Generation was published by Algonquin Books. To commemorate the big day, I found myself booked to do no fewer than thirteen radio interviews, starting at 6 a.m. Pacific Standard Time. As I write this, I’m on tap for eight more today, as well as an evening appearance at one of my favorite indie bookstores, Book Soup. I just hope I can keep my eyes open: I’m normally a stay-up-late kind of gal, but this past week I’ve been springing awake at 4:30 a.m., ready to rumble.

Andy Warhol once predicted that each of us will be famous for fifteen minutes. If so, I’ve had more than my share of fame this week. On Tuesday, November 7, my Seduced by Mrs. Robinson: How The Graduate Became the Touchstone of a Generation was published by Algonquin Books. To commemorate the big day, I found myself booked to do no fewer than thirteen radio interviews, starting at 6 a.m. Pacific Standard Time. As I write this, I’m on tap for eight more today, as well as an evening appearance at one of my favorite indie bookstores, Book Soup. I just hope I can keep my eyes open: I’m normally a stay-up-late kind of gal, but this past week I’ve been springing awake at 4:30 a.m., ready to rumble. Yesterday was an off day—all I had to do was drive from my Santa Monica home to Culver City where National Public Radio has its west coast headquarters. There the adorably blue-haired Leo del Aguila fitted me with oversized earphones and made sure I sounded good on mike. Then suddenly I was talking to Robert Siegel, the senior host of All Things Considered, who turned out to be a fellow Baby Boomer with fond memories of seeing The Graduate for the first time. How nice to chat, both before and after the official interview, with a man blessed with a sonorous voice and a good-humored manner, even if he was speaking to me from thousands of miles away. Ah, the magic of modern communications!

The great thing about radio (just ask Terry Gross!) is that no one cares what you look like. You don’t have to wonder what to do with your hands, nor worry about whether you hold your mouth in a funny position when listening to someone else speak. A bad hair day is no big deal on radio. Theoretically you could roll out of bed, pick up the telephone, and do the interview in your jammies. But media experts strongly advise that you freshen up and put clothes on. If nothing else, that will make you feel more professional. I’ve also been told that it helps to speak standing up, and that moving around will give your voice more energy. That’s why, during radio interviews from my home, you’ll find me roaming around the living room, trying out dance moves (yes, really) and checking out spots that my cleaning lady may have missed.

How do I know what to talk about? That’s easy. I know the contents of Seduced by Mrs. Robinsonas well as the back of my hand. (Better, actually – I don’t spend a lot of time studying my hands.) And all the prep work done by Algonquin is really paying off. All my interviewers have received a press release as well as a list I’ve drawn up containing 20 surprising facts about The Graduate. Especially when a radio host hasn’t had time to actually read my book, I get lots of questions like this one: Which soon-to-be famous movie and TV folk had tiny bit parts in The Graduate? (Answer—future Oscar winner Richard Dreyfuss, who has one line as a college kid, and TV’s Mike Farrell, playing a bellhop at the Taft Hotel.) So far, at least, everyone has been super-friendly. Clearly no one is trying to trip me up. But in any case I know the biggest enemy of radio is dead air, so the essential thing is to KEEP TALKING, no matter what. Funny thing: as a natural-born chatterbox, I have no problem on that score.

If you’re curious to hear the results of my All Things Considered interview, here it is!

Published on November 10, 2017 14:24

November 7, 2017

Just Like Today? Not a Chance

The Academy Awards ceremony of 1980 honored a bold assortment of Hollywood movies from 1979 that touched on major strands of American life. The big winner was Kramer vs. Kramer: Dustin Hoffman and Meryl Streep both finally won their first Oscars for portraying an estranged couple fighting over the custody of their child. If you liked cinematic razzle-dazzle and the sense of genius at work, another major nominee was Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz. If you were leaning toward an epic with contemporary relevance, there was Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam drama, Apocalypse Now. The China Syndrome broached the environmental dangers implicit in nuclear power, while Norma Rae delved into the challenges of the labor movement. But at the moment the 1979 film that strikes me as particularly relevant to our own times is an odd, surreal adaptation of a novel by Polish-born author Jerzy Kosinski. It’s called Being There.

Being There was not a best picture nominee, nor was it recognized for its craft contributions. One of its two Oscar noms was for the film’s star, Peter Sellers, who had personally optioned the material. Sellers was suffering from a weakened heart, and this tightly controlled performance came at the very end of his life. The other nomination, which resulted in a win, was for screen veteran Melvyn Douglas, whose career went back to the very beginning of talking pictures. He made Garbo laugh in Ninotchka (1939) and tried to talk Mr. Blandings (Cary Grant) out of building his dream house (1948). Douglas won his first Supporting Actor statuette as the deeply principled father of Paul Newman in Hud (1963). In Being There, he played a more urbane guy, the wealthy and powerful Benjamin Rand, close advisor to the American president (Jack Warden).

At the center of Being There is Sellers as Chance, a man who’s more than a bit of a cipher. Set adrift at the start of the film by the death of his patron, he’s a childlike figure who seems to know about little more than the estate garden he has tended for so many years. He can neither read nor write, and gets most of his view of the world from watching television. But his elegant clothing (cast-offs from his patron’s wardrobe) and his formal manners give the impression that he’s a person of substance. Through a series of mishaps Chance the gardener is transformed into Chauncey Gardner, It is Douglas’s character, Ben Rand, who welcomes him in, introducing him to American politics on the highest level.

The underlying joke of Being There is that a man who knows little, who can only talk knowledgeably about TV and gardening, is accepted by Rand and his compatriots as a font of wisdom. Representatives of foreign nations start gravitating toward him as well, convinced he has a deep understanding of their culture and language. Booked as a guest on a political talk show, Chance wows the nation with austere Zen-like pronouncements about the state of the world. Soon the President of the United States is feeling threatened by this attractive newcomer to the political scene, and the end of the film suggests that the various powers behind the throne are on the verge of coalescing behind him in the next election.

Upon the original release of Being There, some moviegoers saw it as a metaphor for the rise of actor Ronald Reagan, who was elected to the presidency in November 1980. Today, of course, it’s tempting to make connections to a certain politician who, without pror experience in elected office, has reached the highest office in our land.

Published on November 07, 2017 13:57

November 2, 2017

Richard Dreyfuss: The Hello Guy

The other evening I took a timeout from the work piling up on my desk to watch a charming 1977 romantic comedy, The Goodbye Girl. This film, a box office hit that was nominated for five Oscars, was in a sense playwright Neil Simon’s gift to his then-wife, Marsha Mason. She plays Paula, a Broadway dancer who has terrible luck with men. Her ex-husband, the father of her ten-year-old daughter, was incapable of being faithful And her various romances since that time have all ended badly. As the movie opens, she’s just been dumped by her current squeeze, who’s off to Italy to make a movie. Not only was he too cowardly to break it off in person but he’s secretly sublet their New York apartment to another actor, who appears at her door in the middle of a rainy night expecting to move in. Needless to say, he and Paula end up in an uneasy truce, sharing the cramped (though not by New York standards) space and trying to deal with each other’s worst habits.

That bedraggled and very arrogant actor, Elliot Garfield, is played by Richard Dreyfuss in a performance that’s a tour de force. When he’s not sparring with Paula, he’s trying to rehearse for his big New York stage debut, playing the title role in Shakespeare’s Richard III. Unfortunately for him, his director has an outlandish approach to the material. He believes Shakespeare’s supreme villain acts the way he does not because he’s a hunchbacked cripple but rather because he’s a closet homosexual, “the queen who wanted to be king.” So Elliot, having failed to convince his director to change course, is forced to mince about the stage in stereotypically gay fashion. Audiences, of course, are appalled, and the reviews he garners are a supreme humiliation.

While all this is happening, Elliot and Paula gradually make peace, and eventually end up making whoopee. Is Elliot just another love-‘em-and-leave-‘em guy? Or is he something better? Far be it from me to give away the film’s ending. But Dreyfuss’s performance as Elliot is so vivid and multi-dimensional that he ended up winning an Oscar for Best Actor of 1977. Lest you think it was an easy win, he was up against Richard Burton for his highly charged performance in Equus. Actors in comedies don’t usually snag the big prizes. But Dreyfuss did; at age 30 he was the youngest man to win in this category until Adrien Brody’s Oscar victory for a very dramatic turn in The Pianist in 2003.

Of course The Goodbye Girl wasn’t Dreyfuss’s first stab at movies. He made waves in American Graffiti (1973), The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1974), Jaws (1975) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). But in The Goodbye Girl he entered territory that had been staked out a decade earlier by Dustin Hoffman: that of a romantic leading man who is not classically handsome. When Hoffman was auditioning for The Graduate, he reasoned that the role of Benjamin Braddock was not for him. In the screenplay, Benjamin is a collegiate superstar, who has scored both in the classroom and on the athletic field. Hoffman reasoned that the part should go to someone tall, blonde, and handsome, like Robert Redford. It took a gutsy decision by director Mike Nichols to go with Hoffman: short, dark, a bit clunky, and unmistakably ethnic. After America unexpectedly fell in love with Hoffman, other ethnic (Jewish, Italian) actors for the first time had a chance at being a romantic lead. So here’s to you, Mike Nichols, for making Richard Dreyfuss’s Elliot Garfield possible.

Read much more about the long-term influence of The Graduate in my new Seduced by Mrs. Robinson: How The Graduate Became the Touchstone of a Generation, out November 7 from Algonquin Books.

Published on November 02, 2017 10:28

October 31, 2017

The Witching Hour at the Movies

Halloween, of course, is a good time to talk about witches. Little girls today may trend toward Disney princesses for their Halloween costumes, but their moms and big sisters who want to put va-va-voom into their holiday attire often choose leggy Sexy Witch outfits. The movies are full of witches: cute witches (Bewitched), sultry witches (The Witches of Eastwick), scary witches (who can forget Margaret Hamilton in The Wizard of Oz?), even a maybe-not-there-at-all witch (The Blair Witch Project). In any case, movies that deal with witchcraft are generally going for fun, whether of the benign or the exciting variety.

But there was a time when to be named a witch was akin to a death sentence. Throughout European history outspoken women (and some men) have been accused of witchcraft, and few of them survived to refute the accusation. And that tradition unfortunately persisted in the New World, most famously in Puritan Massachusetts, where in 1692 dozens of local citizens were condemned to the gallows by tribunals determined to purge all witches from their midst.

Years ago, I was featured in several productions of The Crucible, Arthur Miller’s hit 1953 play that draws from the Salem witch trials an indirect parallel to the witch-hunting being done by Senator Joseph McCarthy and the members of the House UnAmerican Activities Committee in his own day. The experience made me want to know more about the reality of the historical event, in which almost twenty locals (14 of them women) were sent to the gallows. Some of the victims were town renegades and cranks, but others were solid citizens known for their piety and good works. How did they come to be accused?

The answer lies in bestselling author Stacy Schiff’s fascinating narrative, The Witches: Salem 1692. Schiff, author of biographies of everyone from Véra Nabokov to Cleopatra, digs deep into the historical record to reconstruct the deadly doings in that small New England town. Much of her focus is on the pre-pubescent girls whose testimony before the witchcraft tribunal brought down so many members of their community. Today we diagnose their writhing and screaming as mass hysteria, but Schiff goes further, seeing in the strict rules of Puritanism the seeds of a covert rebellion that evolved into an impulse to undo others. Conditions in Salem were harsh: not only was daily life an ongoing challenge but a rigid religious system allowed for few emotional outlets. Schiff notes how many of the accusing girls had previously suffered the loss of a parent. She also grasps how easy it was for bereaved children to accuse their father’s new wife of witchcraft.

As an historian, Schiff makes a shrewd observation: “History is not rich in unruly young women; with the exception of Joan of Arc and a few underage sovereigns, it would be difficult to name another historical moment so dominated by teenage virgins, traditionally a vulnerable, mute, and disenfranchised cohort.” Noting that these young accusers’ testimony is often rich in details of brightly colored clothing supposedly worn by the witches on their revels, she wonders: were the accusers themselves so desperate for color in their lives that they turned their forbidden longings into accusations of others?

The first filmed version of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible was made in France in 1957. It featured French-speaking actors like Yves Montand and his wife, Simon Signoret. Hollywood didn’t dare film Miller’s play until the Daniel Day-Lewis version, based on Miller’s own screenplay, appeared in 1996. It contains the very sexy love triangle that Schiff doesn’t find anywhere in the chronicles of Salem Town.

Published on October 31, 2017 08:51

October 27, 2017

Baseball Goes to the Movies (or Root Root Root for the Home Team)

OF COURSE I’m rooting for the Dodgers to win the World Series. I’ve loved the team since it moved from Brooklyn to Los Angeles, putting down roots at Chavez Ravine after a crazy season playing baseball in the historic L.A. Coliseum, where homeruns over the short left-field fence were almost inevitable. I admit these days I’m something of a fair-weather fan, ignoring the team when they are flailing and paying attention mostly when they’re in the thick of a pennant run.

When I was growing up, though, my whole family bled Dodger Blue. That was the era when Danny Kaye performed a hilarious song outlining a hypothetical game in which the Dodgers miraculously whip their arch-rivals, the San Francisco Giants. (Oh really? No, O’Malley.) Not only did I learn the Dodger Song (see below) by heart but I actually seized the opportunity to sing part of it for Danny Kaye himself, when he visited the U.S. Pavilion at Expo ’70. (If you think I wasn’t a bit tongue-tied at that moment, you’re very much mistaken.)

Anyway, now that baseball is in the air, I’m taking the opportunity to wax philosophical about why so many Hollywood movies have baseball settings. I haven’t done a serious survey, but it seems to me there are far more movies about baseball than about any other sport, like football, basketball, tennis, or golf. Why? Maybe it’s for the same reason that baseball has long been considered America’s favorite pastime. Though it of course celebrates teamwork, it also remains the spectator sport that best spotlights the talents of a rugged individualist, the player who can win a game with one pitch or one swing of the bat.

Looking back on the baseball movies of the past, I see that some of the most famous are those that focus on the deeds of a single hero, like Lou Gehrig in 1942’a The Pride of the Yankees. There are also multitudes of movies in which the heroics come from underdogs who unexpectedly rise to the occasion. Witness, for instance, The Bad News Bears (1976, plus a slew of sequels and remakes), as well as A League of Their Own (1992), in which women show that they too have what it takes to play ball.

For some reason the 1980s (the era when the Dodgers last enjoyed World Series play) gave rise to many notable baseball films. Both The Natural (1984, based on Bernard Malamud’s first novel) and Field of Dreams (1989) endow the sport with mythic dimensions. In 1988, John Sayles delved into baseball history’s ugliest moment, the fixing of the 1919 World Series by the Chicago White Sox, in Eight Men Out. Here was a case where the mythology turned dark, in a film highlighting the betrayal of America’s hopes and dreams. Much more fun was the subject matter of 1988’s other baseball movie, Bull Durham, with its focus on sexy fans who’ll do just about anything to show their loyalty to their favorite minor-league team.

In recent years, the heroics of Jackie Robinson, baseball’s first black player, were highlighted in 2013’s lively tribute film, 42. But our cynical era is perhaps best represented by 2011’s Moneyball, a hit movie based on the real-life story of how the Oakland A’s general manager, Billy Beane, used computer-generated analysis to build himself a champion ballclub. It’s a provocative subject, and the film was nominated for six Oscars. But I admit I for one feel machinations in the front office are ultimately less interesting than exploits on the field.

Go Blue!

Published on October 27, 2017 16:50

October 24, 2017

Inching Down the Amazon with Theodore Roosevelt

When I worked for Roger Corman at Concorde-New Horizons, his deal with Lima-based filmmaker Luis Llosa had us sending movie crews to make movies in Peru’s crumbling colonial cities, stark grasslands, and dense jungles Though we used Peru as a stand-in for Vietnam and many other places, we also dreamed up several projects intended to have a true Latin American flavor. One was Fire on the Amazon, an ecological drama that remains special to me both because it contains a Sandra Bullock nude scene (yes, really) and because my rewrite of the script gave me a screenwriting credit I probably didn’t deserve. We also adapted a nineteenth-century Jules Verne novel called Eight Hundred Leagues Down the Amazon into a PG-13 action-adventure that drove us all somewhat crazy. Here’s the official logline: Outlaw Joam Garral makes a clandestine journey down the crocodile and piranha infested Amazon river to attend his daughter's marriage. Not only must he brave the dangers of the Amazonian jungles, but also the bounty hunter hot on his trail. This may sound potentially exciting, but we hardly had the budget, nor the technical know-how, to make an Amazon rafting trip seem really exciting.

I’ve just finished reading a book that makes me glad I never went on an Amazon expedition. Candice Millard is an historian and biographer who once worked for National Geographic. Her first book was a 2005 bestseller, The River of Doubt: Theodore Roosevelt’s Darkest Journey. It chronicles the period in which the 56-year-old Roosevelt, after his White House years and the failure of his campaign to initiate a new political party, plunged with characteristic vigor into an expedition to survey an uncharted Brazilian River known as the Rio da Duvida, or River of Doubt. Among the adventurers who set out with Roosevelt to travel the river from its source to its mouth were the renowned Brazilian military man who had first discovered the river and was dedicated to charting its course, a respected American ornithologist, a medical doctor, a Catholic priest, and Roosevelt’s son Kermit. The latter was a brave and stalwart young man quite accustomed to the rugged life. Though Kermit was along on the trip to watch over his father’s well-being, he was distracted by his recent engagement to a society beauty. Unfortunately, his impulsive decision along the way led to the death of one of the corps of native paddlers who shared in the hazards of the journey.

Roosevelt’s story has everything: dangerous flora and fauna, hostile natives, fearsome rapids, lost canoes. There’s even a buffoon, the priest who assumed that as the physically weakest member of the party he’d be carried through the jungle on the shoulders of others. And there’s a villain too: one of the local laborers (or “camaradas”) on the trip turns out to be a thief and a murderer. As the men approached starvation, Roosevelt aggravated an old injury that weakened him to the point that he seriously contemplated suicide, as a way to keep from holding the others back. He somehow survived, but in three months lost 55 pounds, or a quarter of his normal weight. He returned home to international acclaim, but was never again quite the robust specimen he’d always prided himself on being.

To read Millard’s book is to be reminded of how much exploration has improved since 1914. For one thing, there was no penicillin back then to fight off the infection that nearly drove Roosevelt to take his own life. Some of the expedition’s choices seem foolish in the extreme, but nobility of character is always worth celebrating.

Published on October 24, 2017 13:20

October 20, 2017

A Film Critic’s Holiday

There’s something to be said for a Nancy Meyers movie. It guarantees that the world is a nice place to live in, and that – when all is said and done – love will find a way. Even if we’re talking about something as basic as love of self, which played a key role in the film for which Meyers earned her first writing credit, 1980’s Private Benjamin. Since then she’s had a share of fifteen other writing credits, including such comedic hits as Baby Boom, Something’s Gotta Give, and It’s Complicated. She also directed the last two films on this list, as well as four others. After a grueling week, a colleague of mine named Madeira James (the web genius behind www.xuni.com) suggested I relax by watching her favorite Meyers film, The Holiday. And so I did.

The Holiday (2006) certainly makes for agreeable company. It’s a Christmas movie of sorts, though half of it is set in a sunny SoCal where the Santa Ana winds blow warm and the affluent splash in their swimming pools year ‘round. (There’s also an impromptu Chanukah party, which I found an endearing touch.) Here’s the basic premise: two attractive youngish women are unhappy in love. Kate Winslet is an English newspaper reporter hopelessly in love with a co-worker who relies on her editorial skills while quietly getting engaged to someone else. She lives in a charming country cottage in Surrey, one I don’t think she could possibly afford. Meanwhile, Cameron Diaz is a workaholic with her own L.A. movie trailer company. She lives in a fabulous mansion, but her live-in is a two-timing creep whom she angrily tosses from the premises as the movie begins. Since neither Kate nor Cam wants to face the holiday season alone, they link up on a house exchange website. The deal is that each will spend two weeks in the other’s digs before they return to the reality of their own lives.

Of course, this being a Nancy Meyers movie, romance soon rears its head. In that English cottage, Diaz unexpectedly cute-meets hunky Jude Law. Do they bound into bed? Yes, but . . . it’s complicated. For her part, Winslet (whose sheer joy in discovering Diaz’s swanky surroundings is contagious) meets . . . Eli Wallach? This is not the last film made by the ageless Wallach, who died in 2014 at the age of 98. He must have been about 90 as he took on the role of Arthur Abbott, a crotchety Hollywood screenwriter whose credits go back to the Golden Age. (According to The Holiday, he was part of the team involved in writing Casablanca, having added the invaluable word “kid” to the deathless “Here’s looking at you.”) Now the Writers Guild wants to hold a big bash in his honor, but he’s too embarrassed by his physical frailty to accept the idea. That is, of course, until Winslet steps up and whips him into shape, paving the way for a triumphant evening in which he abandons his walker and almost leaps up to the podium to give his acceptance speech.

Here’s one of many areas in which The Holiday doesn’t make much logical sense. Two weeks are far too short to contain all the activity that this script sets up. But, after all, who’s counting? The actors (including an essential Jack Black) are so charming that we want to believe them. And, despite all the indications to the contrary, we want to believe they can find their happily ever after. Maybe that’s what this film is all about – a holiday from everyday logic.

This one's for Maddee, a delightful and patient lady of many names. If you like the look of my new www.beverlygray.com website, she's the one to thank.

Published on October 20, 2017 12:43

October 17, 2017

Noah Baumbach's Meyerowitz Stories-- All In the Family

Filmmaker Noah Baumbach is something of a poet of family dysfunction. I was impressed by his The Squid and the Whale (2005), though I came away vastly relieved that I had never had to survive the challenges of a split-up family. I feel the same way about Baumbach’s newest release, The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected), which was greeted enthusiastically at Cannes last spring. This film too has a lot to say about the impact of failed marriages on the children of these unions, but its tone is gentler, with occasional glimmers of nostalgia.

Filmmaker Noah Baumbach is something of a poet of family dysfunction. I was impressed by his The Squid and the Whale (2005), though I came away vastly relieved that I had never had to survive the challenges of a split-up family. I feel the same way about Baumbach’s newest release, The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected), which was greeted enthusiastically at Cannes last spring. This film too has a lot to say about the impact of failed marriages on the children of these unions, but its tone is gentler, with occasional glimmers of nostalgia.Don’t expect from Baumbach a tightly-plotted movie. He’s not going to become a Hollywood-style director anytime soon. As his title hints, the film is structured like a collection of linked short stories. He meanders from one character to another, one situation to another, until we have a full multi-generational picture of the Meyerowitz clan, people who were born to drive one another crazy.

Everything starts with Harold, a bearded and paunchy New York sculptor. He’s played with cantankerous panache played by 80-year-old Dustin Hoffman, who’s now worlds away from his role as just-turned-21 Benjamin Braddock in The Graduate. Harold Meyerowitz, modeled after Baumbach’s own grandfather, is a semi-success in his chosen field: the Whitney Museum once purchased one of his pieces, though it now doesn’t quite know where to find it. But he’ll never get over the fact that he lacks the recognition accorded some of his peers. His 33 years as an inspirational art teacher at Bard College seem to mean nothing to him. And he dismisses his three grown children (from two of his four marriages) with a blend of condescension and disdain. This is not a man that most people would find lovable, though his perennially soused current wife (an hilarious Emma Thompson) and his major art-world rival (Judd Hirsch) are firmly in his corner. So are the grown sons who can’t live with him, can’t live without him.

Ben Stiller does well as the neurotic younger son who has besmirched the family name by lacking artistic talent, but now (as a highly successful financial planner) could buy and sell all the other characters. In the awkward position of being his father’s clear favorite, he struggles to make everyone happy while simultaneously wrestling with his crumbling marriage back in L.A. But most of the film’s critical attention has gone to Adam Sandler, for his intricate portrayal of the angry older son. He’s been embittered by his father’s neglect of him from childhood onward, and yet he’s also a good and loving dad to his own daughter, who’s on the brink of her college years. (She aspires to be a filmmaker, and her would-be-bold student films are among the film’s most hilarious moments, especially given that everyone in this artsy family feels obliged to show them high respect.)

I’m not familiar with the TV and stage work of Elizabeth Marvel, who plays the third--and most neglected–-Meyerowitz sibling. As the mousy Jean, she’s poignantly left out of the loop no matter what’s happening. Other small but vital roles are played by Adam Driver (as a petulant celebrity client of Ben Stiller’s character) and Candice Bergen (as an ex-wife with a conscience). The Meyerowitz Stories is hardly straight-ahead filmmaking, but it contains great pockets of delight. Like that awkward MOMA art opening attended by Hoffman and Sandler in matching tuxedoes, and especially the climactic moment when the Meyerowitz half-brothers finally, clumsily, act out their mutual disgust before acknowledging that, after all is said and done, they need each other.

Published on October 17, 2017 11:42

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers