Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 79

April 10, 2018

Black Panther Goes Back to the Future

I don’t pretend to be a connoisseur of superhero movies. And, though I worked on the “lost” Roger Corman version of Fantastic Four (and even briefly met the estimable Stan Lee), I don’t have any special insight into the Marvel Universe. But the cultural conversation aroused by Black Panther—which is now the all-time third-highest-grossing movie at the U.S. box office and is approaching $1.3 billion in ticket sales worldwide—made me eager to see what all the talk is about.

And, yes, Black Panther is well worth talking about. For one thing, it’s a triumph over Hollywood’s usual racial expectations. Here’s an African-American director (Ryan Coogler of Fruitvale Station) given a massive budget to shoot an epic that features an almost all-black cast, none of whom play conventional gangbangers. Women are well represented on screen, not just as love interests but also as brainy scientists and fierce warriors. (If I were being held captive, I’d certainly trust Wakanda’s tough-as-nails all-female military force to spring me.) The movie’s staggering global ticket sales may reflect the pleasure taken by many around the world in seeing people of color kick ass. But Black Panther’s international appeal may also relate to the fact that it’s a truly international production. The imaginary African kingdom of Wakanda may be its chief locale, but an important section of the movie is set in (and shot in) South Korea. The credit roll at the film’s end also mentions locations in Munich and other German cities, as well as Argentina’s spectacular Iguassu Falls and (for interiors) Pinewood Atlanta Studios in Fayetteville, Georgia.

I’m also struck by the fact that so many of the actors come from afar. The British-born Andy Serkis (on-screen, for once, instead of using his famous motion-capture skills) plays a memorably rollicking bad guy. Many of the film’s African characters are not African American but instead have more unusual pedigrees. In major roles there are Letitia Wright (as the brainy scientist character, from British Guyana), Danai Gurira (the feisty female warrior, who grew up in Zimbabwe), Daniel Kaluuya (the Get Out star, from England), Florence Kusumba (from Germany), and the venerable John Kani (once an important stage presence in the works of Athol Fugard, from South Africa). And, of course, the female lead is the impossibly beautiful Oscar winner, Lupita Nyong’o, who hails from Mexico and Kenya.

Somewhat like last year’s DC superhero film, Wonder Woman, Black Panther combines storybook exoticism with futuristic derring-do. But the effect here is far more striking because the juxtaposition of African folk art (animal masks and statuary) with a high-tech city of the future is surprisingly seamless. Kudos to the film’s design team for making disparate elements work so well together. It’s also terrific to see a movie that takes African culture seriously. I was charmed by 1988’s Eddie Murphy flick, Coming to America, but that outrageous movie played African royalty for laughs. Here we’re intended to take the fate of Wakanda’s royal family seriously, and we do.

Coming to America traded on the culture clash between regal Africa and inner-city USA. Black Panther too has something to say about daily life in an African-American ghetto, and it’s hardly treated as a joking matter. To give the film even more contemporary resonance, it ends with a plot twist that can well be called anti-Trumpian. Spoiler alert: the rulers of Wakanda, casting off centuries of secrecy, decide to benignly share their advanced technologies with the rest of the world. No more “Wakanda first” isolationism for them! Who can argue with an idealistic ending like that?

Published on April 10, 2018 12:07

April 6, 2018

“Mildred Pierce”: Revenge of the Waitress

There’s a long tradition of Hollywood hopefuls waiting tables while waiting for their big break. East Coast restaurants may boast waiters who’ve devoted their lives to deftly taking drink orders and serving plates of food. In SoCal, though, if you scratch a waiter (which I don’t recommend), you’ll find a young thespian who’d rather be playing Hamlet or Camille. If you’re served by someone who recites the nightly specials with a highly theatrical flair, you can be sure he or she has a make-or-break audition coming up soon.

On movie screens, most of the food-servers are female, and I can reel off a long list of films in which a waitress is at the center of the story. Think of Ellen Burstyn, winning an Oscar for playing a sassy but sensible waitress in 1974’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. (This Scorsese film lived on as a popular TV series.) Think of Keri Russell baking and serving pies in 1981’s Waitress, which has since evolved into a Broadway musical. Think of Julia Roberts and the other nubile young ladies toiling in a downhome pizza joint in 1988’s Mystic Pizza. Think of Brooke Adams slinging hash in the desert in 1992’s Gas Food Lodging.

Back in the Golden Age, too, many female stars put on those little caps and aprons to play waitresses. At a time when most women didn’t work outside the home, there were few employment choices open to them, and there seemed a bit of sexy logic in associating females with perky uniforms and the serving of food to patrons who were alternately admiring and demanding. When I dropped in on a Michael Curtiz Festival, led by the always-interesting Alan Rode, at UCLA’s Billy Wilder Theatre, I was amused to discover that the glamorous Joan Crawford would be appearing in two Curtiz films in which she had to lower herself to wait tables before rising to the heights of business success. One was a 1949 steamy Southern film noir, Flamingo Road. The other, of course, is the Warner Bros. classic, Mildred Pierce, with Crawford winning an Oscar as an unhappy housewife who remakes herself first as a waitress and then as a budding entrepreneur in the restaurant trade, all to win the love of her heartless young daughter, Veda (Ann Blyth).

As Alan points out in his fascinating Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film , the success of Mildred Pierce as a movie was by no means a sure bet. Yes, it was based on a work by James M. Cain, whose Double Indemnity stories and whose novel, The Postman Always Rings Twice, had enjoyed wild success as film adaptations. Unfortunately, Cain’s Mildred Pierce was both sordid and turgid: it required some creative thinking to give it the pizzazz that movie audiences craved. Producer Jerry Wald, stumped for a dramatic climax, concocted the idea of turning Mildred Pierce into a murder mystery, with a killing in the opening scene but the killer not identified until the end. Many hands, including that of William Faulkner, labored on the script. And many of Hollywood’s favorite leading ladies (Bette Davis among them) turned down the title role. Crawford was available because MGM had let go of her contract, accusing her of being “box office poison.” Mildred Pierce was her chance for redemption, but working with the feisty Curtiz didn’t come easy. In what’s been called “the battle of the shoulder pads,” he rejected her usual elegant look and insisted she play the film’s early scenes as a frumpy hausfrau in a drab little cotton shirtwaist. The furs, of course, came later.

Published on April 06, 2018 09:29

April 3, 2018

Steven Bochco: Singin’ the Hill Street Blues

I can’t pretend I ever met the late Steven Bochco, who died last Sunday at the much-too-early age of 74. But I certainly saw him in action. Back in 1982, I was sent by Theatre Crafts magazine to look in on a hot new TV show, Hill Street Blues. This hour-long NBC dramatic series about daily life in an inner-city police precinct had made its debut in January 1981. At first it attracted few viewers, but by fall it had collected a record number of Emmy awards. Bochco, the series co-creator (as well as its frequent writer and producer) personally earned two 1981 Emmys, for Outstanding Drama Series and for scripting the premiere episode. Later he won additional prizes for such classic shows as L.A. Law and NYPD Blue.

Back in 1982, though, Bochco was still the new kid on the block. He was not the central figure in my magazine piece, which focused not on the show’s scripting but on its pioneering technical aspects. That’s why I hung out mostly with supervising producer Gregory Hoblit, who introduced me to the show’s editor, art director, and sound mixer. But in the halls of the Hill Street Blues production office, Bochco was very much in evidence. Still under 40, he was a lively (and live-wire) presence. When I arrived, there was a pick-up game of baseball going on in the narrow hallway, with Bochco a spirited participant. I quickly skedaddled to avoid being beaned.

It was Greg Hoblit (who has gone on to have his own career as a producer and director) who clued me in to what made Hill Street Blues different from any cop show that had gone before. From week to week, a number of story strands played out simultaneously, with no tidy wrap-up at the end of the hour. This realistic approach also affected the show’s visual and auditory stylistics. Hoblit remembered being handed a pilot script “that in its very essence seemed to call for things being down and dirty and messy. It had a jumble of people—a boiling of cops and street people inside that precinct. It had colloquial dialogue, incomplete sentences, random thoughts, non-sequiturs. And out of that came an inclination to make the film look grimy, to make it look like a Serpico or Dog Day Afternoon.” That’s why the show’s cinematographic choices played up a gritty, grainy look. Hoblit said he’d told veteran cameraman William Cronjager that he wanted the film “to look like the negative had been rolled out on the deck in the morning and a truck had run over it, then stuck back in the camera and shot.” The result won the show one of its first eight Emmys.

A distinctive sound design was also part of the mix. With its multiple overlapping of background tracks, Hill Street Blues was a constant hubbub of telephone calls both close and far away, along with police sirens, typewriters, and human voices. This cacophony made its point about the chaotic atmosphere of a big-city police station. And by avoiding time-consuming “shoe-leather” shots of actors crossing to a ringing telephone or walking from car to doorstep, the show’s editor was able to capture the action’s frenzied pace.

I can’t resist ending with an amusing anecdote. In the Hill Street offices, I came upon the show’s young location manager, whom I recognized as a UCLA graduate-student colleague of mine. When I mentioned his PhD in English literature, he motioned me to be silent. As he put it, if word got out, his reputation on the set would be ruined.

Published on April 03, 2018 09:08

March 30, 2018

Of Bunnies and Buns—An Easter Tail

The celebration of Easter has long been associated with rabbits: cute, fluffy, cartoonish white bunnies who hop around the globe delivering gaily-colored eggs. Getting into the spirit of the holiday weekend (which also includes the start of Passover), I’ve been thinking about the motion picture world’s treatment of bunny rabbits. There’ve been lots of filmed versions of Beatrix Potter’s Peter Rabbit tales (or, I guess, tails), among them the 2018 live-action/CGI hybrid version voiced by such stars as James Corden, Margot Robbie and Daisy Ridley. Also from England, there’s stop-motion genius Nick Park’s full-length Wallace and Gromit adventure, The Curse of the Were-Rabbit.The British must have a thing for rabbits: Lewis Carroll’s ageless Alice in Wonderland is full of them. Hollywood has churned out well over two dozen adaptations of Carroll’s Alice story for movies and TV. Disney’s classic animated film from 1951 of course features an iconic White Rabbit and March Hare. So does the Tim Burton variation from 2010, and also the famous live-action Paramount production from 1933, featuring such mega-stars as W.C. Fields, and Cary Grant. (Charlie Ruggles portrays the March Hare.)

Of course I can’t overlook Bugs Bunny, though that “wascally wabbit” of Warner Bros. cartoon fame is anything but cuddly. It’s a curious bit of trivia that Walt Disney first made his mark not with a mouse but with a rabbit. His “Oswald the Lucky Rabbit” shorts were an early hit for their distributor, Universal Studios. In 1928, when Disney decided to go out on his own, Oswald had to stay behind. So Walt and master cartoonist Ub Iwerks shortened and rounded Oswald’s ears, added a long skinny tail, and voila! Mickey Mouse was born.

There’s one more Hollywood rabbit I have to mention, one who meets an unfortunate end. That’s the pet bunny who gets boiled by bad-girl Glenn Close in 1987’s Fatal Attraction. If you recall, she turns a one-night-stand with married guy Michael Douglas into an obsession, with the femme becoming increasingly fatale as she tries to come between him and wife Anne Archer. Result: rabbit stew.

The success of Fatal Attraction at the box office led, of course, to a proliferation of erotic thrillers by other filmmakers. (You could say the film and its imitators bred like rabbits.) My former boss Roger Corman was always quick to capitalize on any new, lucrative trend, and there was the added advantage that erotic thrillers are cheap to make—little stunt work, no special effects, just a whole lot of boobs and buns. That’s why I found myself, as the Concorde-New Horizons story editor, hard at work on a sexy 1990 rip-off called Body Chemistry, in which two university sex researchers indulge in some extra-curricular hanky-panky, much to the detriment of the male’s formerly happy home life. In our film, the femme fatale, Dr. Claire Archer, lives on, soon popping up in Body Chemistry II (1992) as an on-the-air radio psychologist with a yen for messing up other people’s marriages. By Body Chemistry III (1994), leading lady Lisa Pescia had been replaced by Shari Shattuck, and Andrew Stevens had come aboard both as hunky leading man and as fledgling producer. The director of BCIII was an irrepressible satyr named Jim Wynorski. Jim and Andrew gave me an associate producer credit, and also a featured spot as a lady seeking sexual advice on a radio call-in show. Yup, that’s a gussied up version of me stretched out beside a roaring fireplace, with a phone to my ear.

Too bad I wasn’t on set with Andrew and the bodacious Shannon Tweed for Body Chemistry IV.

Published on March 30, 2018 15:23

March 27, 2018

Aladdin Goes Hollywood

I will always associate Aladdin with the glitz and glamour of Hollywood—both the state of mind and the tawdry but exciting street of that name. Back in 1992 I took my kids to the historic El Capitan, the gorgeously-restored 1926 movie palace at the heart of Hollywood’s Walk of Fame, to see Disney’s animated musical extravaganza. It was preceded by a brief stage show, a reminder of the way movies used to debut in the early days. Then the film itself came on, and we were all blown away by the music, the visuals, the sheer inventiveness, and the rambunctious high spirits of this production. Robin Williams’ shape-shifting genie was of course the comic heart of the film: Genie was a role he was born to play. But everything on screen blended together in a way that was totally magical. Afterwards, we all felt so good that we found ourselves singing and dancing under that brightly lit marquee on Hollywood Blvd., which I’m sure had the local street people scratching their heads.

Flash forward to this past weekend. In 2014, the Disney version of Aladdin became a Broadway musical, capitalizing on Howard Ashman and Tim Rice’s original lyrics and Alan Menken’s spritely score It was nominated for 5 Tony awards, including Best Musical, and the delightful James Monroe Iglehart nabbed a Tony for the featured role of Genie. (No one, of course, can hope to duplicate Robin Williams’ manic appeal, but the stage version of this role adds a jazzy Cab Calloway-style hipness that’s hard to resist.) Aladdin is still wowing Broadway tourists, but a full-scale touring production has recently made its home in another movie palace, this one at the fabled intersection of Hollywood and Vine. The Pantages, built in 1930, to house vaudeville acts in addition to first-run motion pictures, is a masterpiece of art deco ornamentation. It’s full of chandeliers, statuary, and cunningly inlaid tile. Look up and you’ll find the ceiling is an intricate web of gilt carving, set against a blue-lit artificial sky that seems made for a magic carpet ride.

Once upon a time, the Pantages was the site for the annual Academy Awards ceremony, and it’s easy to feel like a movie star when you’re ushered in. The six-year-old with me was attending his first big theatrical production, and his eyes were bright with wonder. He laughed and clapped, oohed and aahed when the stage was briefly lit up by fireworks, and fortunately didn’t squirm in his seat enough to make other theatregoers sea-sick. As for me, I too was charmed. It was fascinating to see what changes needed to be made to put an animated cartoon on stage. Gone were such lively Disney-esque sidekicks as a sinister parrot, a mischievous monkey, a cuddly tiger, and a personality-plus magic carpet. Instead, Aladdin got three human buddies, Jasmine (in this me-too era) was more overtly feminist, and elaborate costume transmogrifications were part of the stage razzle-dazzle. In tribute to our Hollywood locale, Genie added a Wakandan salute to his bag of tricks, and “accidentally” pulled an Oscar statuette from his pocket instead of a magic lamp.

After the show we strolled down Hollywood Blvd., only to discover crowds milling around an elaborate grungy “vertical trailer park.” This was a come-on for a a pop-up attraction designed to generate interest in the new Spielberg futuristic thriller, Ready Player One, which opens March 29. We couldn’t resist queuing up to tour a maze complete with flashing lights and brain-teasers. The look was dystopian, quite a contrast to the lavish exotica favored by Hollywood of old.

Boy with lamp

Boy with lamp Vertical trailer park

Vertical trailer park

Published on March 27, 2018 13:32

March 23, 2018

Michael Curtiz: He’s No Angel

To those of us who are fascinated by early Hollywood, director Michael Curtiz has always been a puzzlement. He was born Manó Kaminer, began his professional life as Mihály Kertész, and (once he moved from his native Hungary to the U.S.) evolved into a flag-waving American known as Mike. He shrugged off his Jewish heritage as easily as he cast aside his several out-of-wedlock children, yet was consistently loyal both to his brothers and to his second wife’s growing son. (Bess Meredyth, officially married to Curtiz until his death in 1962, was a prolific screenwriter who participated in all her husband's screen projects. Her son John Meredyth Lucas went on to become a director as well as a producer on such hit shows as The Fugitive and Star Trek.)

During a fifty-year career that covered some 170 film projects, he proved himself a total workaholic, taking pride in always being the first one on the set. Yet he also loved retreating to his expansive San Fernando Valley ranch, and (outside of sex with every sweet young thing who struck his fancy) his favorite form of recreation was polo. One thing about him was consistent: his total inability to stop mangling the English language.

I get my information from a colleague, Alan K. Rode, who’s no stranger to contradiction. A former naval officer, he spent years dividing his time between writing and toiling as an aerospace general manager before committing himself fully to chronicling the history of classic Hollywood. His love for the entertainment industry is deeply rooted: his mother and several other family members were all once involved in film production. Aa a lifelong movie buff, Alan has interviewed and befriended many of the stalwarts of Golden Age Hollywood. His special passion for film noir has led him to be active as both a commentator and a preservationist. He’s one of the leading lights behind the Film Noir Foundation, and helps host the nation’s various Noir City film festivals, as well as his own Arthur Lyons Film Noir Festival in Palm Springs. He curated UCLA's recent three-month Curtiz retrospective, and this April he'll be appearing on TCM with Ben Mankiewicz, spotlighting Curtiz's Hollywood career.

When I first met Alan, he had one book under his belt: Charles McGraw: Biography of a Film Noir Tough Guy. But he told me then he was laboring over something really big. Big it certainly is—Alan’s Michael Curtiz: A Life in Film is a jumbo-sized volume from the Screen Classics series put out by the University Press of Kentucky. It’s a serious, critically acclaimed survey of the director’s long career. In it I learned about Curtiz’s skill with a camera, his fraught relationship with his home studio, Warner Bros., and his involvement in making everything from Captain Blood to Casablanca (for which he won an Oscar) to Life with Father to the Bing Crosby musical, White Christmas. Errol Flynn, Olivia de Havilland, and Bette Davis became stars on his watch. In addition, James Cagney brilliantly shifted gears in his George M. Cohan biopic, Yankee Doodle Dandy, and Joan Crawford—making a comeback after being sacked by MGM as “box office poison”—won an Oscar for her title role in Curtiz’s Mildred Pierce. He was the first to make movies starring John Garfield and, much later, Doris Day. (Seeing Day, a popular band singer, as possessing unmistakable star quality, he forbade her to take acting classes.) In 1958 he directed Elvis Presley in the film generally considered his best, King Creole.

Curtiz’s achievements don’t entirely make up for his shenanigans—like his temper tantrums and the late-career big-budget botch called The Egyptian in which both he and producer Darryl Zanuck cast their mistresses in featured roles. Rode discusses, in fascinating detail, how Curtiz ended up making a movie, Mission to Moscow, that could be considered a Soviet propaganda film, but then emerged from the McCarthy era wholly unscathed. Some in Hollywood loved him; some hated him. But one thing’s for sure—without him, Hollywood would have been a much less interesting place.

Published on March 23, 2018 10:50

March 19, 2018

"Annihilation": Gals with Guns

Here there be spoilers.

Sometimes the audiences are smarter than the critics. Though science fiction is not my favorite genre, I went to see Annihilation because a family member went to high school with Tessa Thompson, a rising star who plays one of the five brainy, gutsy women (Natalie Portman leads the pack) at the center of the drama. Tessa was always a charmer, and I wanted to check out what she was up to. Then there was the fact that the writer and director of Annihilation, Alex Garland, had earlier given us Ex Machina, an eerily effective thriller about all-too-human robots. And the critics I read made Annihilation sound both visually stunning and intellectually fascinating: a cerebral mind-game with art-film overtones (think Russia’s Andrei Tarkovsky).

Don’t believe everything you read. I saw the film on a Saturday night in a nearly empty theatre, an indication of the public’s general disdain for the blather that Annihilation puts forth as challenging futuristic ideas. Yes, it’s potentially of interest that, within the mysterious force-field known as “the shimmer,” the DNA of various species (including the human) recombines to form new beings. But I never got the sense that anyone had bothered to think through the implications of this concept. Questions abound. Like -- why is the fate of each member of Portman’s all-female team of scientists and general bad-asses so different? Why – spoiler alert -- is Portman the only one of the five who makes it through to the end of the movie? I’ve tried to logic this out, and come up with the only possible conclusion: Portman’s character survives, in a shell-shocked but still fundamentally human state, because she’s the star of the movie.

Over the years, when working with writers and directors, I’ve clung to a basic principle when it comes to screenplays: you’ve got to know the rules of your world. Even if – especially if -- you’re dealing in fantasy or science fiction, the filmmakers need to grasp the parameters of what they’re creating. Not that the audience must be force-fed every crumb of information: we viewers often have to do some mental work in order to be rewarded with an understanding of what’s going on. The trouble is that in Annihilation I didn’t feel anyone had a full grasp of the world the film sets in motion. You can only get so far why saying that the universe is a mysterious place.

Here’s an example of the vagueness that had me so frustrated: lots of screen-time is devoted to hints about Portman’s marriage to a soldier (Oscar Isaac) who had gone missing on a mysterious mission, but then resurfaces under strange conditions. Late in the film we discover that she’s had a passionate affair with another man, and that she suspects that Isaac suspects. OK, but how does this tie into anything? Personally, I think her romantic complications are just the filmmakers’ excuse to throw another sex scene into the mix.

Then there are her comrades in arms, Tessa Thompson among them. Their backstories are summed up in a sentence or so, full of hints about past traumas. But, frankly, these women seem to have no interior lives. Nor, really, does Portman. Why the heck did she serve several tours of duty in the military (developing weaponry expertise) before becoming a professor of biology? Call me a Roger Corman-style cynic, but I think the all-female cadre of scientists on this mission is just an excuse for enticing scenes of Gals with Guns.

Intellectual mind-games? How about intellectual claptrap? Watching this movie pretty much annihilated me.

Published on March 19, 2018 23:07

March 16, 2018

Stephen Hawking: To Infinity and Beyond

Not long ago, in an event sponsored by the City of Pasadena, I heard the late Stephen Hawking speak. Or, to be precise, he was present in the hall, and his voicebox was doing the speaking. I don’t remember anything he said, but I know he was charming and funny. And I’ll never forget the sense of awe that filled the room as he was escorted up the aisle. We all knew we were in the presence of a very special being.

Why was Stephen Hawking such a memorable figure? Surely it wasn’t because of his scientific achievements, which most mere mortals could barely understand. I suspect we loved him because he gave off a sense that man—even a man with a fragile and rapidly degrading body—could accomplish anything he chose. Despite the indignities of early-onset ALS, Hawking managed to live a life of achievement, making scientific breakthroughs, writing a best-selling book, and taking part in scholarly debates about the nature of the universe. He also had a full emotional life, which included two marriages and three children. And he was able to enjoy the perks of global celebrity, including humorous guest-star appearances on Star Trek, The Simpsons, and The Big Bang Theory. So what if he wasn’t a good candidate for Dancing With the Stars? In terms of public acclaim, he had it all.

Including, of course, an award-winning movie about his life. The Theory of Everything was a 2014 British film, based on Jane Hawking’s memoir, Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen. The film begins at the University of Cambridge, where a young, slightly nerdy student of astrophysics and a pretty literature major fall in love. As their romance progresses and Stephen plunges into the study of black holes, he is diagnosed with motor neuron disease. Though the future looks bleak, Stephen and Jane marry and start a family. And so it goes, with the marriage fraying as Stephen’s body disintegrates. Still, everyone behaves fairly nobly, and the ending is what critics have called “triumphant.” The film was nominated for five Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Actress (Felicity Jones). In a big year for biographical portraits—including Benedict Cumberbatch as Alan Turing in The Imitation Game, Bradley Cooper as Chris Kyle in American Sniper, Steve Carell as John du Pont in Foxcatcher, and David Oyelowo as Martin Luther King in Selma—the little-known Eddie Redmayne won the Best Actor Oscar for impersonating Stephen Hawking.

Redmayne vividly captures Hawking’s personality, but of course part of the role’s award-bait potential came from the chance it gave the able-bodied young actor to show Hawking’s gradual physical self-destruction. Surely there’s no scientific way to choose a “best” actor or actress, since each of the nominees has taken on a very different sort of role. That being said, Oscar voters often favor those who display the most dramatic physical transformation. Think, for instance, of Daniel Day-Lewis as a cerebral palsy victim in My Left Foot. Think Tom Hanks battling AIDS in Philadelphia and Matthew McConaughey doing the same in Dallas Buyers Club, with both actors losing copious amounts of weight in order to be convincing. Then there are the heavy makeup roles, with actors rewarded for their ability to put forth a convincing characterization from beneath loads of Latex. .This year’s winner, Gary Oldman, was brilliantly transformed into Winston Churchill. His role in Darkest Hour required of him both solid acting chops and hours in the makeup chair.

I salute Eddie Redmayne’s performance, but Stephen Hawking was one in a billion. Our universe is poorer without him.

Published on March 16, 2018 12:19

March 13, 2018

Fear of Flying: How Airplane Movies Evoke High Anxiety

It started out as a simple flight, a short Sunday afternoon hop from Tucson to L.A.. I was returning home from the Tucson Festival of Books, where I was treated like a celebrity, even to the point of being chauffeured to the airport by a very friendly festival volunteer who offered cookies and good cheer. (Hey, Jude -- thanks for the lift!) When I discovered that my 5 p.m. flight would be delayed by an hour, I took it in stride, even though the news that the plane had not yet left LAX was far from encouraging. Eventually the departure time was changed to 6:15, and then pushed a bit later. But when the passengers arriving from Los Angeles debarked, things started looking up.

It started out as a simple flight, a short Sunday afternoon hop from Tucson to L.A.. I was returning home from the Tucson Festival of Books, where I was treated like a celebrity, even to the point of being chauffeured to the airport by a very friendly festival volunteer who offered cookies and good cheer. (Hey, Jude -- thanks for the lift!) When I discovered that my 5 p.m. flight would be delayed by an hour, I took it in stride, even though the news that the plane had not yet left LAX was far from encouraging. Eventually the departure time was changed to 6:15, and then pushed a bit later. But when the passengers arriving from Los Angeles debarked, things started looking up.It was one of those tiny jets – two seats on either side of the aisle -- that seemed to have been left over from an earlier era. There was some confusion about which roller bags would actually fit in the overhead compartment, and which would have to be checked and then (hopefully) retrieved at the other end. But I was on the plane, and it seemed as though we were about to head for home. And then . . . we weren’t. Slowly, slowly, our mini-jet inched back toward the terminal, without any real explanation from the crew. We were told to sit tight, and to use the one tiny bathroom if we chose. I inched my way to the aft of the plane, and discovered a young couple desperately trying to sooth a toddler who couldn’t be persuaded to go to sleep.

And then . . . a uniformed airport police officer walked down the aisle, glancing to his left and right. At such a moment it’s easy to feel guilty—what have I done NOW? And, in today’s uncertain political climate, it’s even easier to feel scared. Was there, perhaps, a terrorist aboard, or an out-of-control crazy, or a disgruntled airline employee determined to wreak revenge? To my surprise, two sheepish-looking young women were quietly escorted off the plane. The word was that they’d been drunk and disorderly in the rear of the vehicle, though from my seat I had seen and heard nothing. The remaining passengers looked stunned, and then we all waited for arrival of the refueling truck. After that, things were uneventful, though I felt sorry (but not too sorry) for passengers with tight connections to Paris and Madrid.

What does all this have to do with movies? It was for me a vivid reminder of why so many film thrillers, past and present, are set on planes. For most of us, flying is mysterious business. We understand it no better than we can grasp how Harry Potter soars into the air in a game of Quidditch. No matter how many times we’ve flown the friendly skies, the enormity of flight can seem a bit overwhelming. So it’s totally credible that things can go, in the blink of an eye, horribly wrong, and that passengers and crew may suddenly find themselves in a life or death situation. Filmmakers have been capitalizing on this fear as far back as 1954’s The High and the Mighty. Whether it’s a storm, a terrorist, an impaired pilot, an attack of food-poisoning, a flock of Canada geese, or snakes on a plane, it’s all too easy to convince the audience that the skies are not so friendly after all. The Graduate’s Benjamin Braddock, though, flew to LAX quite uneventfully. It was only when he touched ground that the trouble began. But that’s another story.

Published on March 13, 2018 12:20

March 9, 2018

Say the Secret Word: Plastics

Big news in the small but star-studded enclave of Malibu, California: the city council has just voted to ban disposable plastic straws, plastic coffee stirrers, and plastic eating utensils from its restaurants. Starting this June, Malibu’s Starbucks and McDonald’s branches will have to find other ways to serve their customers who want to sip a soda or stir Splenda into a venti half-caf 2% extra-foamy latte. It’s not just that the Malibu celebrity crowd is full of environmental bleeding hearts, though there’s certainly some truth in that. Malibu, of course, is a city with miles of glorious coastline, and the residents know all too well that plastic straws and other non-biodegradable items often end up on beaches. When swept out to sea, they do irreparable harm to fragile ocean creatures. That’s why Malibu has taken the lead, as it did when it was one of the first California cities to ban plastic supermarket bags.

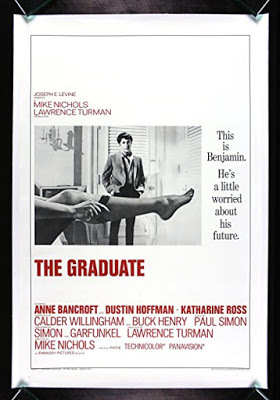

When I think of plastic spoons, straws, and stirrers, my mind immediately turns to the “just one word” that a man named McGuire promises young Benjamin Braddock in The Graduate. The scene is Ben’s coming-home party, where all of his parents’ affluent SoCal friends are gathered to welcome this new college alumnus into adult life. Out by the swimming pool, McGuire intones, like an oracle, the word he’s convinced can be Ben’s Open Sesame into a world of economic satisfaction: Plastics. This immediately became a laugh line, to the point where screenwriter Buck Henry griped that the audience was soon shouting “Plastics!” before Mr. McGuire had even opened his mouth.

The word “plastics” immediately signified, to the bright young moviegoers who were the first to claim The Graduate as their own, a career based on rampant materialism rather than personal satisfaction. Plastics were exactly what these young graduates did NOT want from their own lives. Like Benjamin Braddock, they hoped their future would be . . . different, and they had no wish to be slaves to impulses that were purely capitalistic. What exactly did they want out of life? Peace? Freedom? Love? All of the above? They (or I should rightly say we) weren’t sure, but plastics were nowhere on that list.

But in my research for my new Seduced by Mrs. Robinson: How The Graduate Became the Touchstone of a Generation, I’ve discovered that in many ways the makers of plastic have had the last laugh. Jeffrey L. Meikle’s scholarly American Plastic: A Cultural History (1995) admits that “to understand both the resonance of The Graduate and instantaneous emergence of ‘plastic’ as a synonym for fake or phony, one must bear in mind the degree to which plastic never escaped the stigma of the second-rate imitation.” But he also chronicles the ways in which plastic, as a strong and versatile material, seems to have taken over the world we live in. (It’s not all negative. Today, in fact, plastic can give us some truly miraculous assets, like the artificial body parts that can be fabricated by 3-D printers.)

My favorite article about the role of plastics in American life was published in Time in 1997. A Time journalist visiting a convention of plastics manufacturers discovered that Mr. McGuire’s advice to Ben was fundamentally sound: “Over the past 30 years, the plastics industry has grown faster that the gross national product.” Nor did those in attendance bear the film any ill-will for dissing their profession. In fact, many of them had first looked into plastics after seeing the film. Said one, appreciatively, “The Graduate was a hell of an advertisement for the industry.”

Mr. McGuire tells Ben the facts of (economic) life

Mr. McGuire tells Ben the facts of (economic) life

Published on March 09, 2018 10:00

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers