Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 75

August 28, 2018

Exit Laughing: The Movies of Neil Simon

In two days, we’ve lost two very different men I consider American heroes. John McCain lacked for nothing when it came to courage and valor: brave in wartime, he later bucked political tides in the U.S. and had the guts to make friends across the aisle. Neil Simon wasn’t called upon for acts of physical bravery. But in writing 32 Broadway plays and almost as many screenplays, he increasingly used his comic gifts (not to mention the details of his own uneasy upbringing) to comment shrewdly on life in 20th century urban America.

I have a special affection for Neil Simon’s brand of comedy because over the years it has brought so much joy to my own family. Take, for instance, The Odd Couple, which started life in 1965 as a hit Broadway play. This story of a slob and a neat-freak rooming together after the breakup of their marriages resonated so strongly with audiences worldwide that in 1968 Simon adapted his script for film. (This is the rare movie comedy that begins with a serious stab at a suicide attempt.) Walter Matthau found movie stardom by recreating his Broadway role as the slovenly Oscar, while Jack Lemmon took on Art Carney’s stage role as Felix. But what my parents and I loved best was the TV version that took to the airwaves from 1970 to 1975, starring Jack Klugman and Tony Randall. Remarkably, Simon’s simple premise led to years of hilarity on this series as well as several follow-up shows, one of them an animated series involving a fastidious cat and a sloppy dog.

Screen versions of Neil Simon comedies brought serious accolades for a number of actors. Maggie Smith won her second Oscar for her hilarious turn in California Suite. Comic George Burns, almost 80, nabbed an Oscar and launched a brand-new acting career as an over-the-hill vaudevillian in The Sunshine Boys. In 1977, when Simon wrote The Goodbye Girl directly for the screen, I doubt he suspected that this amiable romantic comedy about another sort of odd-couple living arrangement (between a hard-luck dancer and a neurotic actor) would garner five Oscar nominations, including Best Picture and Best Original Screenplay. Perhaps the evening’s biggest surprise was young Richard Dreyfuss winning the Best Actor statuette over the much more serious and more celebrated Richard Burton (for Equus), as well as Marcello Mastroianni, John Travolta for Saturday Night Fever and Woody Allen for Annie Hall.

As a chronicler of The Graduate, I’m particularly interested in the strong link between writer Neil Simon and director Mike Nichols. Nichols, casting around for a viable career after partner Elaine May broke up their sketch-comedy act, was asked to direct a very early Neil Simon play about newlyweds in a New York walk-up. Under Nichols’ assured direction, Barefoot in the Park became a palpable hit, running for 964 performances. On the strength of this play’s success, Nichols was invited by producer Larry Turman to direct his very first movie, The Graduate. He came quite close to casting the play’s leading man in the plum role of Benjamin Braddock. Though Robert Redford ultimately lost out to Dustin Hoffman, his endearing 1967 performance in the screen version of Barefoot in the Park (opposite Jane Fonda) helped move him into the bigtime.

One other Graduate connection: eight years after her slinky and audacious turn as Mrs. Robinson, Anne Bancroft was cast opposite Jack Lemmon in Simon’s The Prisoner of Second Avenue, about a laid-off exec driven crazy by life in New York City. Whodathunk she’d be so convincing as a loyal, loving, thoroughly frazzled urban wife?

Published on August 28, 2018 11:42

August 24, 2018

Touched by Lubitsch: Smiles on a Summer’s Night

Why Lubitsch? It’s been a hot, sticky summer, marred in my home state by actual fires, rather than the flames of passion. So I decided to chill out with two pre-Code Ernst Lubitsch confections. Lubitsch people, it seems, live in places like Paris, sip cocktails at all hours, wear tuxedos (men) and slinky satin gowns (women), and make amorality into a fine art. They don’t all have money, but they know how to get it, or how to live beautifully without much at all. In these films from the early 1930s, made several years before the Hays Code imposed rigid moralistic restrictions) the outside world (of politics, of economics, of conventional behavior) rarely intrudes at all.

Lubitsch, a German Jew who began as an actor, came to Hollywood in the silent era, imported by Mary Pickford to direct her in a film called Rosita. Their collaboration didn’t go well, but he was soon snapped up by the major studios. His first outing as a director of talkies, 1932’s Trouble in Paradise, is considered his very best by many film historians, including my buddy Joseph McBride, whose new book is titled How Did Lubitsch Do It? This spritely comedy—which features the sexy and well-dressed triangle of Herbert Marshall, Miriam Hopkins, and Kay Francis—is the story of two grifters determined to pilfer the expensive jewels and accoutrements of a naïve but beautiful widow, heiress to a cosmetics fortune. When Marshall and Hopkins first meet over a romantic dinner in Venice, they are both posing as aristocrats. The scene in which they discover their mutual talent for pickpocketry is priceless. Suffice it to say, they steal each other’s hearts (along with a wallet, a gold watch, and a garter), but Kay Francis’s more soignée charms become for Marshall a serious distraction.

The witty screenwriter for Trouble in Paradise was a Lubitsch regular who became a Hollywood favorite: Samson Raphaelson. (Among other things, he wrote the play that ultimately became The Jazz Singer.) A different kind of writing talent was on display in Lubitsch’s next feature, 1933’s Design for Living. Though it was based on a hit Noel Coward stage comedy, the Lubitsch version had entirely different characters and structure. Coward had written the roles of two men and a woman engaged in a jolly ménage à trois to accommodate himself and good friends Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne. Apparently he’d dabbled in giving them exotic backgrounds (with himself cast as a Chinese gentleman), but settled for making them posh, artistic Britishers, one male a successful playwright, one a much-admired painter. Since the men’s longtime friendship much pre-dates the entrance of the charming Gilda into their lives, their intense attachment to one another is another aspect of the triangle, and suggests glimpses of Coward’s own not-so-covert homosexuality.

The Lubitsch version (script by the great Ben Hecht) turns all three characters into Americans abroad, first seen on a train in their down-and-out days. In a tour-de-force opening sequence, Gilda (Miriam Hopkins) first encounters the two men (Frederic March and Gary Cooper) in a third-class compartment, snoring away. Nothing daunted, she proceeds to sketch them. When they awaken to discover this vivacious young blonde and her sketchpad, all three launch into fluent traveler’s French, as they hotly discuss the merits of her work. The legendarily laconic Gary Cooper speaking French? And engaging in sparkling repartee? All part of the Lubitsch touch.

Director/screenwriter Billy Wilder, himself famous for such charming films as The Apartment and Some Like It Hot, posted a sign in his office: How Would Lubitsch Do It? We’d still like to know.

Published on August 24, 2018 10:22

August 21, 2018

Pageant of the Masters: Frozen Fun on a Warm Evening

Ultimate Challenge sculpture, Huntington Beach, CA

Ultimate Challenge sculpture, Huntington Beach, CA What do Arrested Development and Gilmore Girls have in common with the artsy seaside community of Laguna Beach, California? Episodes of these two well-loved TV series have borrowed from Laguna Beach the concept of a pageant in which live performers pose, frozen in place, to simulate famous works of art.

These tableaux vivants (or “living pictures”) are an old-fashioned idea, from the days well before TV and movies, when entertainment needed to be simpler and more home-grown. I remember from my girlhood a sweet scene in Louisa May Alcott’s 1880 novel, Jack and Jill, in which the novel’s main characters posed as characters from American history, culminating in one young fellow impersonating Daniel Chester French’s famous statue, The Minuteman. But the impulse to mimic sacred works of painting and sculpture can be traced back to the Medieval church. And, centuries later, titillating shows like the Ziegfeld Follies enjoyed turning semi-draped young women into living sculpture.

Enough history lesson! Laguna’s so-called Pageant of the Masters, which has been around since 1933, is a triumph of community spirit. Hundreds of local volunteers, under the direction of a small and devoted paid staff, gather each summer for eight weeks of posing in the name of art appreciation. And a quarter of a million viewers gather in comfortable outdoor surroundings to marvel at what costumes, lighting, stage sets, and deep dedication can do. A lively narration, a few dancers, some gimmickry. and a live orchestra playing appropriate tunes add much-needed pizzazz: there is only so long you can marvel at living paintings before you start wanting SOMETHING to break up the stillness.

The 2018 theme is “Under the Sun,” featuring works of art set in natural surroundings. Some are by true masters like Monet and Gauguin: the Laguna folks ably reproduce impressionistic oil paintings set in Giverny and Tahiti. But this year’s pageant also salutes artists closer to home, including a few twentieth-century plein air painters who were involved in the festival’s founding. There are also some imaginative touches, like reproductions of those enticing California citrus labels, with their Indian maidens and bathing beauties on full display. Just for fun, this scene is punctuated by giant plastic “oranges” that bounce across the stage, to the crowd’s delight.

My favorite section, though, focuses on one of California’s favorite outdoor sports: surfing. The orchestra strikes up a Beach Boys tune, and skateboarders whiz through the Irvine Bowl as a prelude to the curtain opening upon an ocean vista. Video projections (much used throughout the pageant to enhance our sense of nature’s majesty) here bring us the crash of ocean waves—waves much like those real ones a short walk away, just off the Laguna strand. But the highlight, of course, is the reproduction of a painting. It features a young man in an impossible pose, not moving a muscle while he crouches on his board, the surf spraying up behind him as he barely avoids a wipeout.

Several minutes later, there’s the depiction of another work of art featuring a surfer. This is Edmund Shumpert’s bronze statue, “Ultimate Challenge,” which immortalizes an iconic male figure riding a curl. The original stands in nearby Huntington Beach, which has officially dubbed itself Surf City U.S.A. The figure on the stage has been made up to look like bronze; somehow invisibly strapped to his board, he slowly turns on a revolving platform to give the audience the chance to see him in the round. His thighs must be silently screaming, but it’s a gnarly sight. Better, I’m sure, than George-Michael Bluth posing as Michelangelo’s Adam in the (almost) altogether.

Poster featuring a local posing as a surfer

Poster featuring a local posing as a surfer

Published on August 21, 2018 09:36

August 17, 2018

Los Angeles: Movies, Water, and Wacky Religion

Los Angeles, as we all know, came into its own as a world-class city largely on the strength of the entertainment industry. When the moviemakers of old moved west, enticed by SoCal’s climate, scenic opportunities, and distance from east-coast pieties, L.A. developed its personality as a city of creativity, ambition, and comfortable lifestyle choices. Historian Gary Krist has previously captured the origin stories of New Orleans (Empire of Sin) and Chicago (City of Scoundrels); his new book, The Mirage Factory is subtitled Illusion, Imagination, and the Invention of Los Angeles. Starting out with L.A.’s liabilities – “often bone dry, lacking a natural harbor, ad isolated from the rest of the country by expansive deserts and rugged mountain ranges”—he establishes how this implausible spot zoomed past San Francisco and became one of America’s largest, richest, most memorable burgs.

Krist has done his homework. I cringed, though, when he flubbed the first name of the man who dreamed of creating a new Venice—canals, gondolas, and all—a short distance from the Pacific shore. It’s Abbot (not Albert) Kinney, and he’s been memorialized via a prominent Venice, CA boulevard. But I admire the way Krist has chosen to probe the three main strands of early L.A. life by focusing on three unique and powerful individuals. Discussing the start of the film industry, he chronicles the up-and-down career of D.W. Griffith, who pioneered many of filmmaking’s most essential techniques. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation was the first big national blockbuster, and also (through its presentation of the Ku Klux Klan as a heroic force) had grave social consequences for American life, as Spike Lee points out in his new BlacKkKlansman. Griffith continued to experiment as a director and producer, and continued to be revered by his former troupe of actors, but the end of his life was a sad one, as the rise of the studio system, coupled with new aesthetic tastes, left him on the sidelines.

Krist’s second major player is a name well known to all Angelenos: William Mulholland. (Yes, he too has a street named after him, that romantically winding byway that snakes along the crest of the Santa Monica Mountains.) Mulholland, a self-educated Irish immigrant, was for years the superintendent and chief engineer of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. He was responsible, through both foresight and a bit of chicanery, of bringing to the thirsty Los Angeles basin water from the Owens Valley. Once his 230-mile aqueduct was completed, L.A. had what it needed to fuel a population boom that has yet to slow down. Some aspects of Mulholland’s achievements (and his personality) have been worked into the character of Hollis Mulwray in Robert Towne’s script for Chinatown. But the movie does not explore the tragedy of the St. Francis Dam disaster of 1928, in which Mulholland’s miscalculations caused 600 deaths and essentially ended what had been a glorious career.

Along with water and movies, Krist sees as essential to the rise of L.A. a common fascination with new spiritual paths. His exemplar here is the very colorful Aimee Semple McPherson, whose Foursquare Gospel Church was a Pentecostal ministry that attracted thousands. The Angelus Temple built by Sister Aimee near Echo Park still welcomes saints and sinners. Growing up in L.A., I was accustomed to viewing McPherson as a fraud and a schemer, especially given her hugely mysterious disappearance and later reappearance (she claimed she’d escaped kidnappers) in 1926. Krist is able to point out more appealing aspects of her character. But I’m surprised Hollywood hasn’t truly gotten its hands on her story.

Published on August 17, 2018 09:28

August 14, 2018

A Room with a Popular View: The World of Merchant Ivory

There’s been much talk recently about the Marvel Universe, and how it might be affected by the Motion Picture Academy’s controversial new plan to add an Oscar for Best Popular Film. At present, no one knows what the criteria for “popularity” might be, and there’s legitimate concern that the Academy Awards might be turning into a People’s Choice-type competition. (Best Screen Kiss, anyone?)

One thing’s certain: the new Oscar will not be won by a Merchant Ivory sort of production. The longstanding partnership that produced such major costume dramas as The Bostonians, Howards End, and The Remains of the Day had no interest in superhero flicks. The movies of the Merchant Ivory Universe are quiet, literate, sumptuously filmed, and usually based on novels by British and American masters. Their target audience: former English Majors, I’m quite sure. Like me.

When James Ivory won a 2018 Oscar for adapting Call Me By Your Name into a screenplay, the Academy was perhaps honoring the Merchant Ivory partnership, the longest in the history of independent cinema. Producer Ismail Merchant and director Ivory were together for 44 years, as both professional and domestic partners. Their nearly 40 films, many of them award-winners, generally also called on the talents of screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabala, who won two Oscars for her work. It was an exotic collection of talents and nationalities. Merchant (who died in 2005 at age 68) once said: "It is a strange marriage we have at Merchant Ivory . . . I am an Indian Muslim, Ruth is a German Jew, and Jim is a Protestant American. Someone once described us as a three-headed god. Maybe they should have called us a three-headed monster!"

All of this is running through my head because I just finished re-watching 1985’s A Room with a View, a classic (and, of course, classy) Merchant Ivory production that competed for 8 Oscars and won three (for adapted screenplay, art direction, and costume design –those creamy white suits for the men and flowing Edwardian gowns for the ladies). The film is based on E.M. Forster’s 1908 novel about sheltered young Lucy Honeychurch who blossoms into a woman in love in the aftermath of a trip to Italy. The film begins at the pensione where a gaggle of affluent Brits on holiday uphold their English standards as a bulwark against the raw Italian passions they encounter in the piazzas of Florence. It’s a reminder, for one thing, of how splendidly the British train their actors, and how well they succeed at conveying lovable English eccentricity. Among the supporting cast are Judi Dench as a romantically-inclined lady novelist, Denholm Elliott as an armchair philosopher, Simon Callow as a jolly parson, and Daniel Day-Lewis as an oh-so-stuffy fiancé. Best of all is Maggie Smith as a prim maiden aunt who drives everyone crazy while insisting that they not worry about her in the least. The romantic center is played by nineteen-year-old Helena Bonham Carter, in her “English rose” period, a far cry from her eccentric look and behavior in such recent films as Oceans Eight.

I’m, not certain viewers will find in A Room with a View much social relevance for the current age. This is escapist fare, with a bit of smart commentary about the pruderies and the cultural imperialism of a bygone era. Amusingly, the one bit of possible controversy involves three of our major characters frolicking quite starkers in a local swimming hole. All three are male, and their behavior is childishly innocent. Quite a neat contrast to the passionate male nudity in Call Me By Your Name.

This Puccini aria, sung by Kiri te Kanawa, beautifully sets the mood for A Room With a View

Published on August 14, 2018 12:29

August 10, 2018

Puzzling Over Kelly Macdonald in Puzzle: Not Slamming the Door

I admit I have a favorite jigsaw puzzle, saved from my children’s growing-up years. It has 300 extra-large pieces and features lots of friendly Disney characters. It’s just complicated enough to give me a mental workout, but just simple enough to keep me from turning into a nervous wreck.It can be done in an hour or so, but I wouldn’t dream of timing myself. That would spoil the fun.

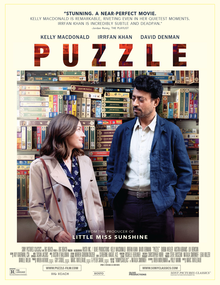

I just saw a new film, though, in which jigsaw puzzling provides a lifeline for a repressed woman who badly needs something new in her life. Puzzle, a small indie made by Hollywood veterans, provides Scottish actress Kelly Macdonald (I’ll never forget her film debut in Trainspotting!) with a quiet but complex role that makes great use of her appealing presence. In the film, she’s Agnes, wife to a suburban mechanic, mother to two grown sons, baker of birthday cakes (even for herself), and a pillar of the local Catholic church. Her husband adores her in her happy homemaker role, and is quick to tell the world how “cute” she is. We sense, though, that something is missing. She’s so used to being agreeable that her own opinions are never voiced.

Her unlikely evolution begins when she tears open a plastic bag containing the 5000 pieces of a brand-new jigsaw puzzle, someone’s casual birthday gift. Agnes discovers in herself a talent for pattern, color, and shape that allows her to quickly solve the puzzle – and feel a sense of personal accomplishment she’s previously never known. Then, on a stealthy trip into New York City to visit a puzzle store, she finds herself drawn into the world of competitive puzzling (who knew there was such a thing?) and her life is changed forever. Her unexpected new puzzle partner is veteran Indian actor Irrfan Khan, playing a man who’s everything she’s not: wealthy, educated, cynical, and from a faraway land. His long list of time-tested puzzling strategies immediately clashes against her own much more intuitive approach. But as they hold practice sessions for the big competition she’s still keeping secret from her family, their relationship blossoms in unexpected ways.

Yet in some respects the relationship that most fascinates me is that between man and wife. Husband Louie, played by the burly David Denman, is convincing as a good-hearted blue-collar guy who loves his wife but believes it’s his job – as a male and the household’s sole provider – to make all the big decisions without consulting her. Lacking much ambition himself, he can’t see that his wife and his eldest son are restless for new challenges in worlds he knows nothing about. Ultimately Agnes reveals to him (and to herself) how much she’s changed, in an ending that is both surprising and completely satisfying.

It took me a while, after the house lights came up, to see the connection between Agnes’ psyche and that of one of literature’s most classic heroines. In the 1879 drama, A Doll’s House, Henrik Ibsen’s Nora, -- of a much higher social class than Agnes and Louie --is an adored little “wifey” whose function in her household is primarily to be ornamental. When she dares to act on her own, we can figuratively say that the roof caves in. Nora’s third-act exit from her comfortable life proved to be a door-slam heard ‘round the world. Agnes slams no doors, nor does she make any big speeches, but her final action is her own quiet declaration of independence. Where it will finally lead her we’re not sure, but I for one am firmly on her side.

Published on August 10, 2018 08:37

August 7, 2018

Running Out of Sand . . . and Time

What crosses the minds of movie lovers when they think about sand? I’m betting they first recall a scene from Lawrence of Arabia: that mesmerizing view of Omar Sharif, on camelback and wearing full Arab regalia, slowly materializing out of a distant mirage and crossing the Sahara to protect his precious well. Then there are the Mad Max films, in which a sandy post-apocalyptic landscape is filled with blood, guts, and the roar of motorcycles. Art film enthusiasts may remember Teshigahara’s haunting Woman in the Dunes: a schoolteacher collecting insects in coastal dunes misses his bus home and ends up spending the night in the house of a local widow. She lives at the bottom of a sand quarry, and in the morning he discovers he cannot leave. (Naturally, existential dread ensues.) A more cheerful view of sand shows up in those 1960s beach party movies, where pretty girls wear bikinis and Annette Funicello cavorts with Frankie Avalon.

What crosses the minds of movie lovers when they think about sand? I’m betting they first recall a scene from Lawrence of Arabia: that mesmerizing view of Omar Sharif, on camelback and wearing full Arab regalia, slowly materializing out of a distant mirage and crossing the Sahara to protect his precious well. Then there are the Mad Max films, in which a sandy post-apocalyptic landscape is filled with blood, guts, and the roar of motorcycles. Art film enthusiasts may remember Teshigahara’s haunting Woman in the Dunes: a schoolteacher collecting insects in coastal dunes misses his bus home and ends up spending the night in the house of a local widow. She lives at the bottom of a sand quarry, and in the morning he discovers he cannot leave. (Naturally, existential dread ensues.) A more cheerful view of sand shows up in those 1960s beach party movies, where pretty girls wear bikinis and Annette Funicello cavorts with Frankie Avalon.But Vince Beiser’s view of sand is a great deal more nuanced. Vince is an L.A.-based investigative journalist interested in social justice, technology, and all things environmental. I first became aware of him when I was selecting a panel of award-winners for a conference of the American Society of Journalists and Authors. Vince had published, in Wired, a fascinating article called “The Deadly Global War for Sand.” It detailed a murder that took place in 2013 in a rural Indian village. The killers were part of a criminal gang. The victim had repeatedly gone to the authorities, trying to stop the thugs from illegally mining a valuable local resource: sand. “That’s right,” noted Vince in his article, “Paleram Chauhan was killed over sand. And he wasn’t the first, or the last.”

Vince’s investigations in India, which included a moment when his own life was in danger, have now led to a major new book, due out today, titled The World in a Grain: The Story of Sand and How It Transformed Civilization . Here’s how he introduces his subject: Except for water and air, sand is the natural resource that we consume more than any other—more than oil, more than rice. Every concrete building and paved road on Earth, every window, computer screen and silicon chip, is made from sand. It's the ingredient that makes possible our cities, our science, our lives—and our future.

And, incredibly, we’re running out of it.

Who knew? But by the time I’d finished Vince’s book I was a great deal more knowledgeable about what he calls “the most important solid substance on earth.” Sand (as a key ingredient in concrete, for instance) has been essential in the building of our buildings and the paving of our roads. For Southern Californians, it’s not just something that pours out of our shoes after a beach trip. No—it’s helped to create our skyscrapers, our freeways, our picture-windows, our swimming pools, and our sunglasses. And, of course, our computers. But not every kind of sand will suit every purpose. Sand’s purity, and the size and strength of its grains, make all the difference. That’s why sand thieves are at work across the globe, stealing primo-quality sand for high-rises in Singapore, pristine beaches in Florida enclaves, and whole man-made luxury islands in the Persian Gulf. Take the 120 million cubic meters of sand that have been piled up to create Dubai’s Palm Jumeirah, a zillionaire’s oceanic hideaway.

It’s an intensely dramatic story, and Vince’s taut prose mines it for all it’s worth. In the process, he convinces the reader that something must be done before we come up empty.

Published on August 07, 2018 10:13

August 3, 2018

Sweets for the Sweet: Willy Wonka meets The Cakemaker

This past weekend was a fattening one, not least because I saw two very different movies that both focused on sweet-tooth delights. I watched 1971’s Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory with a very excited six-year-old who knew the Roald Dahl original and was thrilled to see it come to life on the screen. This was not the 2005 Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, starring Johnny Depp in a performance that perhaps reflects Dahl’s own perverse sense of humor but has also creeped out kids and adults alike. In Willy Wonka, the candy man is played by Gene Wilder as a fellow full of mischief, one who’s unpredictable when faced with bad behavior but remains ultimately benign. Those all-seeing blue eyes, that Harpo Marx hair – I’d like my Willy Wonka to look like that.

This past weekend was a fattening one, not least because I saw two very different movies that both focused on sweet-tooth delights. I watched 1971’s Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory with a very excited six-year-old who knew the Roald Dahl original and was thrilled to see it come to life on the screen. This was not the 2005 Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, starring Johnny Depp in a performance that perhaps reflects Dahl’s own perverse sense of humor but has also creeped out kids and adults alike. In Willy Wonka, the candy man is played by Gene Wilder as a fellow full of mischief, one who’s unpredictable when faced with bad behavior but remains ultimately benign. Those all-seeing blue eyes, that Harpo Marx hair – I’d like my Willy Wonka to look like that.Which is not to say it’s a film without flaws. Though I enjoyed the ageless Jack Albertson as Grandpa Joe, finding his footing after years spent in bed, the movie’s essential Charlie Bucket did nothing for me. As young Charlie, Peter Ostrum comes across as a nice kid, but not one with any particular charm or complexity. (Perhaps that’s why he never made another movie. He’s had what’s perhaps a much saner life, as a husband, father, and veterinarian.) Attempts to add suspense into the plot via an apparent industrial spy are lame, at best. And the film’s musical numbers, including a would-be poignant ditty sung by Charlie’s mother early in the film, can only be described as saccharine.

Speaking of sugar, I’ve got to add that the wonders of Willy Wonka’s candy factory (a chocolate waterfall, candy cane trees, and so forth) do not look especially mouth-watering. The film contains a few clever visuals (I like the wall-hook that snatches Grandpa Joe’s hat), but it didn’t make me especially hungry for a trip to the candy store. By contrast, The Cakemaker quickly set my mouth to watering. If you like scrumptious cinnamon cookies, not to mention a chocolate-and-cherry Black Forest Cake, you will find yourself wondering where you can go after the movie for a quick pick-me-up.

Black Forest Cake is actually the American translation of Schwarzwälder Kirschtorte. It’s appropriate to give the German original here, because this film is a rare Israeli-German co-production. No, it’s not Holocaust inspired, though the mistrust that Jews might feel for Germans, even today, is part of its backstory. The central character is Thomas, a young German baker who’s a master of his craft. The tragic death of someone he loves brings him to Jerusalem, where he shyly insinuates himself into the life his lover left behind. The Cakemaker is not a movie that overexplains itself, and viewers are left to decide on their own the motives and emotions of all the central characters. This is a pleasure that’s somewhat rare when it comes to Hollywood movies; I’ve discovered that the film’s ending, in particular, can lead to serious post-screening discussion over that yummy piece of cake. Curiously, I’ve found some evidence that men and women see the ending quite differently, especially in terms of the behavior of the film’s female lead. Is it love she’s after, or closure, or what exactly?

Suffice it to say, without spilling all this movie’s secrets, that The Cakemaker explores relationships between Berlin and Jerusalem, male and female, religious and secular life. (The unbending observance of Jewish dietary laws forms an important element of the plot.) How tasty to see a film that gives the viewer so much to chew on.

Published on August 03, 2018 10:34

July 31, 2018

Enter Dancing: The Inexhaustible Erica Brookhart

That's Erica on the left

That's Erica on the leftErica Brookhart lives for stories. She tells them through dance; she tells them through words; she tells them through video. If you sit down beside her over a glass of pinot noir, you might find yourself sharing lurid family secrets. Thanks to evolving technology, Erica can continue to make her living by running a dance studio for kids, while also churning out children’s picture books (like Chico Learns Ballet) and contributing a deeply-moving documentary to YouTube. I met her in Zumba class, where she’s a twice-a-week mainstay. Being Erica, she has recently turned the foibles of our classmates and instructors into a short comic film, Save My Spot, to tickle the funnybone of Zumba lovers everywhere.

Erica started out in Colorado. At college she majored in journalism, gaining communication skills and learning her way around technological gadgetry. Then, upon graduation, she toured Bosnia, Kosovo, and other European hotspots as a dancer entertaining American troops. She toted along a small digital camera with which she hoped to shoot footage for a documentary. That didn’t work out, but later she used her skills to record the bout with cancer faced by her close friend and roommate, a fellow dancer. When Ercia started filming Trycia, the plan was to chronicle a survival story, showing how this vibrant young woman beat the odds. Alas, it was not to be. Over the course of five years, Trycia weathered many challenges, living long enough to bust out the dance moves (along with her new groom) at her own joyous wedding celebration. But Erica’s camera also recorded her friend’s decline, leading to her death in 2012. The result is sad, but by no means somber, showing how to live life to the fullest even after being handed a death sentence. Erica’s finished documentary, Enter Stage 4 , has racked up 70,000 views on YouTube. Says Erica now, “I didn’t make the film to make it big, but it’s been helping people all over the world.”

Her most recent YouTube project is a great deal more upbeat. Once she put out the word that she was making a fifteen-minute short, friends stepped forward to offer equipment and services like camerawork and production design. She persuaded her mother and sister to take feature roles, and herself played the bubbly sis of the central character. To skewer the obsessive nature of Zumba folks, she also recruited one of her own teachers, Ali Cesur, to vamp his way through a routine. (Of course he’s an aspiring actor – this is SoCal, after all.) Then she announced in class that she needed Zumba enthusiasts to dress crazy and shake their booties. More than twenty of them showed up at a borrowed gym on a weekend, and stars were born left and right. No, you won’t find me there: I was away on a speaking engagement. But I love seeing my gym rat pals strut their stuff.

You can find out more about the very sparkly Erica Brookhart on her website: http://ericabryn.com/ There you’ll see her dancing onstage with Michael Jackson and performing her Britney Spears tribute routine. (Video has many uses in her life.) And her next big project? Well, she’s about to get married to a fitness instructor-turned-sports-equipment-salesman. His name is Rob Robinson, and so she looks forward to becoming the new Mrs. Robinson. She stays in touch with the parents of her late friend, Trycia, and plans to incorporate fabric from Trycia’s gown as part of the “something borrowed” in her own wedding ensemble. The dancing there should be show-stopping.

Published on July 31, 2018 11:59

July 27, 2018

The Sounds of Silence: Poland’s Mesmerizing “Ida”

Ida, set in 1962, reflects what happened to the Jews of Poland during and after the second World War. Its title character is a devout convent-bred novice, on the brink of taking her final vows, who unexpectedly discovers that her dead parents were Jewish. Though Holocaust dramas are sometimes rather cynically seen as awards magnets, it’s narrow-minded to look at Ida solely through its depiction of the murderous treatment of Polish Jews under the Nazi regime. Against all odds, Wanda and Anna forge a relationship based on their common bonds. It’s one that takes the film in an unexpected direction, one that I won’t betray. Suffice it to say, though, that Anna (née Ida) turns out to be more surprising than we might have predicted. She may have been raised to know nothing more than convent life, but her brush with the outside world makes its mark. Not—I hasten to add—that she exactly chooses a modern path. We’re left, finally, with more questions than answers.

In the service of his characters, Pawlikowski has chosen filmmaking techniques that are highly unusual. The film is shot in stark black and white, using an old-fashioned aspect ratio that often reduces characters to a small speck in the bottom corner of the screen. Moreover, from scene to scene his camera shows virtually no movement. So what we’re seeing, as we cross rural Poland, is fixed pictures, in which the characters are merely blips inside their all-encompassing environment. Many years ago, Roger Corman instructed me to read Siegfried Kracauer’s Theory of Film. It’s a long, rather ponderous book, but it makes the point that the magic of cinema is all in its visuals. This film illustrates Kracauer’s belief system in a way that’s not ponderous at all, but rather powerfully dramatic.

Not only is Ida visually static, but it’s at times almost silent. Dialogue is next to nil: by contrast, it’s fair to say that most Hollywood films -- dependent as they are on bright verbal exchanges -- seem downright obstreperous. Often, watching this film, we know what’s happening through what is not said. It’s a method that draws the viewer into the film, making us pay close attention to nuance, to facial expression, to glimpses that we may or may not have seen. Bravissimo.

Here's a link to a very smart New York Times review of Ida.

Published on July 27, 2018 12:24

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers