Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 71

January 11, 2019

Escaping from a Room With a Clue

It was bound to happen. There’s a new low-budget suspense thriller out with the provocative title, Escape Room. (Here’s the catchline: Solve the Puzzle. Escape the Room. Find the clues or die.) I haven’t seen Escape Room, but I doubt it’s terribly good. Still, as a former Roger Corman person, I give this project high marks for hitting on a topic that’s both timely and commercial.

Escape rooms, of course, seem to be our latest fad. I’ve experienced two, and enjoyed the fun of using logic and bursts of inspiration to find my way out of a colorfully decorated but decidedly locked chamber. Escape rooms have various themes, some of them quite gruesome. But my family and I chose fairly innocent escapades, involving wizards and magic. And it was always made clear to us that an unseen overseer was monitoring our progress, so there was no chance of our being trapped forever.

I’ve just learned that the escape room phenomenon began in Eastern Europe. Hungary, in fact, has dubbed itself the Escape Room Capital of the World, and I’m told that much of the clever apparatus at my last escape room was imported direct from Budapest. It’s provocative to muse about why escape rooms are currently flourishing in the former Soviet bloc. Perhaps, if you have memories of living under Russian domination, you relish the idea of using your wits to burst out of bondage and recapture your personal freedom. Or maybe I’m getting carried away.

But it’s certainly true that almost all of us are susceptible to claustrophobia. And the makers of horror films have long used that fact as a way to scare us silly. Horror films remain popular among filmmakers because their limited locations and small casts make them cheap to produce, and also because they have a way of tapping into our deepest fears. That’s something Roger Corman certainly knew back in the 1960s when he was filming Edgar Allan Poe stories like “The Pit and the Pendulum” and “The Premature Burial.” Corman’s Poe films had Gothic trappings, but other claustrophobia-inducing films of the era are set in the present day, like 1964’s Lady in a Cage, in which Olivia de Havilland is trapped in a home elevator, and mayhem ensues.

The idea of being trapped perhaps reaches a pinnacle of sorts in the Saw franchise, which began in 2004. Sawstarts, as you may recall, with two men finding themselves in chains, locked in a mysterious bathroom, with only a corpse and a pair of hacksaws to keep them company. Playful malevolence is the watchword here: our characters are caught in a sadistic game whose rules elude them. It’s clear there are some clever minds at work behind the scenes in Saw, but as one of the characters approached the necessity of hacking off his own foot I decided this was one film I didn’t need to watch to its conclusion.

We tend to like horror films (and escape rooms) because we know that at some point the lights will come up and we will return to our own reality. Unfortunately, the horror doesn’t always end when the game is over. In my daily newspaper, I just read a tragic story from Poland: five teenage girls died when the old building housing their escape room caught on fire. Locked by the operator into a tiny closet-like chanber, they had no way out. No one was able to reach them in time, and smoke inhalation caused their senseless deaths. A very sad story—and one that will doubtless soon be coming to a theatre near you.

Published on January 11, 2019 11:14

January 8, 2019

Trying Not to Yawn on Beale Street

Well, the Golden Globes have just been handed out. In the drama category, all three of the BLACK films have come up empty. I’m talking about Black Panther, BlacKkkKlansman, and If Beale Street Could Talk, all of which tackle the African-American experience in somber terms. Among the musical and comedy nominees, the statuette was won by Green Book, which presents black-white relations in a far more positive light. Perhaps it’s true that the small cadre of Golden Globe voters, those sometimes eccentric members of the Hollywood Foreign Press, prefer their race-based stories to be uplifting. Or perhaps those three black films cancelled each other out, paving the way for the surprise victory of (huh?) Bohemian Rhapsody.

No matter. I was eager to see Beale Street for several reasons. First, it’s based on a James Baldwin novel I’ve never read. Baldwin, a masterful writer, loved movies. During a brutally unhappy childhood, he went to movie matinees for solace and inspiration. But he was hardly above criticizing films he felt demeaned the African-American experience. (His feisty book-length essay from 1976, The Devil Finds Work, contains a critique of Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones that is just plain hilarious.) Baldwin’s lack of faith in Hollywood probably helps explain why his other novels have not been filmed. I noticed in the end-credits of Beale Street a heartfelt thank-you to the James Baldwin Estate. I’m guessing he did NOT want Tinseltown monkeying around with his work.

Which brings me to reason #2. If Beale Street Could Talk was adapted as well as directed by Barry Jenkins, the young African-American who brought the Oscar-winning Moonlight to the screen in 2016. As someone who admired Moonlight (though not finding it entirely gripping as a drama), I wanted to see what Jenkins would do next. He didn’t disappoint. Beale Street revels in his trademark lushness of color, sound, and texture, particularly in its swoony interaction between two young (and very attractive) lovers, played by newcomers KiKi Layne and Stephan James. Tender family scenes, especially those involving the young heroine’s supportive mother, lively father, and high-spirited sister, also made their mark. And no one who sees this film will soon forget the outrageousness of justice denied: as a kind of antidote to the good-hearted cops of BlacKkkKlansman, Beale Streetshowcases how a policeman with a grudge can callously destroy an innocent young life.

The word is that Jenkins had been working on the script for Beale Street since back when he was turning an unpublished play into Moonlight. But here’s the tricky thing about adaptation: novels, in particular, are much longer than movies. So they tend to contain far more material than any movie can handle. The challenge is to know what subplots to cut; otherwise, the resulting film will be full of loose threads, leaving us to wonder just how we got from point A to point B. I could list at length some of the frustrations presented by Beale Street. For example, what happens to the hero’s God-fearing, evil-minded mother later in the story? She certainly makes her presence felt early on, when the full implications of young Tish’s and Stephan’s plight are presented to her. So where does she go thereafter? And when the heroine’s loving mom, played by the justly-celebrated Regina King, flies off to Puerto Rico in a desperate bid to save her daughter’s lover, what is the plot logic behind her behavior? Yes, her trip sparks a dramatic confrontation, but the journey itself never makes much sense. All this clutter of detail ultimately bogs down the action, leaving me annoyed instead of inspired.

Published on January 08, 2019 12:30

January 4, 2019

“First Man” and “The Wife”: A Tale of Two High-Flying Achievers (and their spouses)

First Man, based on a biography of Neil Armstrong, is the story of the first human being to walk on the moon. The Wife, a screen adaptation of Meg Wolitzer’s novel, concerns a woman who lives in her husband’s shadow. At blush, the real-life story of a celebrated man and the fictional tale of an overlooked woman wouldn’t seem to have much in common. But for me these two films (one of which I saw on an airplane and the other in a hotel room) spark a lot of deep thoughts about the role played by gender in two twentieth-century success stories.

As portrayed by Ryan Gosling, who tamps down his usual sparkle for this role, Neil Armstrong is the epitome of the strong silent type. A military man and an apparently fearless test pilot, he is a natural for the early astronaut corps. There is never any question about his competence and courage. His only apparent weakness lies in a deep-seated inability to talk a good game. He’s just not gifted (in the way of someone like John Glenn) when it comes to schmoozing the press and the public. When called on to make a grand pronouncement about his role in the upcoming moon mission, he can only stammer out a slightly awkward statement about being pleased to be chosen. Fortunately, the American people are charmed by his modesty.

According to the film, Armstrong’s natural reticence grew more intense when his young daughter died, at age 2, of a brain tumor. He mourns her in silence, unable to share his emotions even with his loyal wife Janet (played by Claire Foy, who seems to be making a career of playing both English queens and American historical icons like Ruth Bader Ginsburg). When Armstrong takes mankind’s first steps onto the lunar surface, it’s little Karen he’s thinking about, not the glory he’s bringing to the United States of America. Keeping one’s feelings locked inside is a classic male reaction to personal tragedy, but Armstrong seems to be an extreme case. The key moment in the movie comes when, going off to be launched into space, he tries to avoid any parting words to his two young sons. That’s when meek, supportive Janet finally fights back, firmly reminding him of what’s at stake: “You're gonna sit them down. Both of them. And you're going to prepare them for the fact that you might not ever come home. You're doing that. You. Not me. I'm done.” (No wonder the marriage didn’t survive, though officially it lasted for 38 years.)

The Wife opens with a long-married couple in bed. Husband Harry (Jonathan Pryce) initiates sex, mostly because he’s too keyed-up to sleep. Both he and his compliant wife Joan (Glenn Close) know that in the wee hours of the following morning, Harry may be told that he’s won the Nobel Prize for literature. The movie contains flashbacks to the early years of their marriage, but primarily it follows the couple on the trip to Stockholm where he will claim his prize, one that he does not exactly deserve. The Wife is effective because it is not the obvious story of a heel and a doormat. These two care about each other, and – even when the cracks in their union become all too apparent – they can turn in a flash from fury to mutual joy or genuine concern. Still, in an era marked by #MeToo, this is a film that recognizes how a woman’s power can be subverted, even as she permits herself to be used and abused in the name of love.

Published on January 04, 2019 11:56

January 1, 2019

Cuba’s Las Parrandas: Of New Year’s Parades and Christmas Eve Floats

My annual New Year’s tradition is to start the day (not too early, please!) by watching Pasadena’s Tournament of Roses parade on television. Somehow I can’t get enough of the brass bands and ingenious flower-covered floats, despite the TV commentators’ mindless chatter. Then, on January 2, I make the trek to the small city of Sierra Madre to enjoy the parked floats up close and personal. As everyone knows by now, Rose Parade floats are required to be covered with natural matter: mostly flowers, but also leaves, seeds, and all manner of vegetables. Like, for instance, potatoes serving as cobblestones, or artfully placed lemons and ornamental cabbages suggesting an under-the-seascape. To view the floats in person is to appreciate the craftsmanship that makes them so spectacular.

Of course such craftsmanship is costly, requiring a whole cadre of designers, flower-growers, builders, and so-called petal pushers who lovingly put every bloom and seed-pod in its proper place. Though the Rose Parade attracts a handful of cities and organizations who do the work on a volunteer basis (with the two Cal Poly universities winning many prizes for their home-grown creations) most floats are funded by big corporations, and are brought to life by well-paid professionals. I can’t complain: the results are gorgeous.

Still, dedicated amateurism is something to be prized, especially when it’s generated by community spirit. I was reminded of this lesson on a recent trip to the Cuban town of Remedios. Luckily for me, Christmas Eve was fast approaching, and so I was able to share in the excitement of a unique Cuban celebration, Lax Parrandas. Las Parrandas de San Juan de los Remedios began in the late nineteenth century when a local priest sought to channel the high spirits of Christmas eve by launching a fiesta that included a midnight mass. The town’s neighborhoods were divided into two groups, with every local being designated either a Rooster (Gallo) or a Hawk (Halcón). Leading up to midnight, the two sides still compete fiercely, seeking to outdo one another by way of fireworks, stationery displays, and floats that are ceremonially rolled into the town plaza at 3 a.m. Each side chooses a theme (which is often movie-related). All details are top-secret until they are unveiled in the course of the festivities. Yes, there’s that brief religious interlude, but mostly this is an intensely secular event, fueled by what a certain tour guide I know describes as Vitamin R. (Of course, this means rum.)

Along with my fellow Road Scholars travelers, I was lucky enough to visit a local designer affiliated with the Roosters, and then move on to a tour of the Hawk workshop where the finishing touches were being prepared. (Yes, we were sworn to secrecy.) At the workshop, which was housed in a large warehouse-style building, we watched loyal volunteers and a few state-supported professionals labor to install simple electronics, paint small lightbulbs in brilliant colors, and carve figurines out of large blocks of Styrofoam. The theme, clearly connected to movie as well as literary imagery, was The Chronicles of Narnia, and I was amazed by the spectacular rendering of a giant lion, as well as three-dimension polar bears, reindeer, and other exotic creatures. (In 2017, the rival team had pinned its hopes on The Snow Queen: Cubans seem fascinated by tales of arctic frost.)

Unlike the Rose Parade, Las Parrandas includes no official judging of the year’s best efforts. It’s all in the bragging rights, and each team is cheered on by its local partisans. I won’t take sides, but will merely say Olé, and Feliz Año Nuevo!

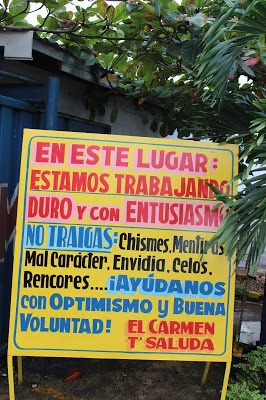

Sign exhorting volunteers to have the right attitude

Sign exhorting volunteers to have the right attitude

Published on January 01, 2019 15:00

December 27, 2018

A Star is Boring

A friend recently told me he was shocked – shocked! – to find the ending of A Star is Born such a downer. Frankly, I was shocked that he was shocked. This is, after all, the fourth time that Hollywood has seen fit to film this particular story. Yes, the details have changed from version to version: the rising actress and the plummeting actor of the 1937 Janet Gaynor/Frederic March iteration had turned into pop singers by 1976, when Barbra Streisand and Kris Kristofferson took on the iconic roles. But throughout the decades, the ending is always pretty much the same. As the female newcomer acquires fame and fortune, her mentor-turned-spouse enters a downward spiral that has tragic consequences.

The current version of A Star is Born is the brainchild of Bradley Cooper, who made this project his debut as a film director, while also co-writing and starring as fading country-rock superstar Jackson Maine. Cooper does a creditable job in all departments, though for me his efforts are not enough to save the film from seeming rather lugubrious and trite. Still, it gave me some matters to ponder, like the all-important role of image in Hollywood, a subject with which this version flirts but does not fully explore.

Cooper, who comes off in interviews as diligent and intelligent, has explained what he did to prepare for his role. There were the daily singing lessons, of course, but he also worked with a coach to lower the pitch of his speaking voice. His goal was to acquire something of a Sam Elliott whiskey baritone, and he ultimately persuaded Elliott himself to appear as his older brother in the film. I can remember back to the days when Cooper played not the leading man but the dorky rejected suitor (see Wedding Crashers from 2005, in which he looks tubby and awkward). Then eleven years later he was named People’s Sexiest Man Alive, a sign that his image had changed considerably.

While transforming himself for his role in a Star is Born, Cooper also worked the magic of transforming pop icon Lady Gaga into an actress, one who has proved nuanced enough to attract major awards attention. It’s no accident that during the filming he addressed Gaga by her actual birth name, Stefani. This small gesture seemed to highlight the fact that he wanted her to get out from under her flashy pop princess persona and tap into the vulnerable young woman underneath. So instead of a rather garish platinum blonde, we first see a fragile brunette, one who comes alive when she sings but otherwise reveals herself to be a mass of uncertainties. Later, of course, once the world has heard her voice, her trajectory is so rapid that she metamorphoses before our eyes into a polished stage performer.

One agent of this change, of course, is Cooper’s character, the first to believe in her singing and songwriting skills. But she also quickly acquires a hot-shot manager, Rez (played by Rafi Gavron), who’s skillful at molding her into a superstar. So the young woman who values her own authenticity is suddenly acquiring back-up dancers and a glitzy wardrobe. Rez even suggests she go blonde. She bats aside that idea, but is soon sporting hair that is screaming red. Stardom changes her; but she also changes rather radically in order to achieve stardom. An interesting concept, but not what this movie is fundamentally about. Cooper’s Jackson Maine disintegrates not because she’s sold herself out but because he’s got problems of his own. Ho hum. Too bad we’ve seen it all before.

Published on December 27, 2018 17:08

December 25, 2018

Roma: Women and Children First

Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma is a simple film in terms of its storytelling, but nonetheless it packs a wallop. This evocation of Cuarón’s own childhood in a section of Mexico City, circa 1971, centers on the woman who seems (to get literary about it) to represent what T.S. Eliot has called “the still point of the turning world.” Not that Cleo would ever have heard of the famous poet. A small, compact figure recruited from the Mexican countryside to serve the family of an affluent doctor, she is quiet, stoic, and possibly illiterate. (With the household cook, she casually alternates between Spanish and her native Mixtec tongue.) Without complaint, she tends to the family’s four rambunctious young children, cleans up after the household pets, trudges to the rooftop to do laundry, and is a silent witness to the widening rift between husband and wife. She still, though, has time for a private life. In her free hours, she goes to the movies, and is courted by a young man who shows off (in the nude) his expertise in martial arts. As she watches him from a rumpled bed, her eyes glow with placid contentment.

But this is a film filled with premonitions of disaster: an earthquake, a near-collision, a mysterious fire, and a bloody riot (known to history as the Corpus Christi Massacre), in which the police mow down leftwing agitators on the streets and in the shops of Roma. So we quickly expect the worst for Cleo. When she confesses her pregnancy, her boyfriend quickly vanishes. Surprisingly, the mistress of the house accepts her situation with equanimity, and even kindness. Cleo is clearly too valuable to the family to be turned out on moral grounds.

This middle-class doctor’s wife seems a harsh figure at first, but it’s soon clear she has troubles of her own. In fact, I found her role quite a fascinating one. She too knows what it’s like to be betrayed by the man she loves. Her agitation is revealed in her disastrous driving (and parking) ineptitude, but she has a heroic side as well, stifling her personal grief in order to protect her children’s innocence. Life without father, she insists to them, will be an adventure! She makes this statement at a seaside resort where Cleo—in a suspenseful scene breathtaking in its power—will risk everything for those same children. Her love for them, we feel, is what allows her to keep on keeping on.

Servitude is for Cleo both a necessity and an ingrained sense of her place in the natural order. It is also, at the best of times, a labor of love. When, at rare intervals, she feels herself loved in return, all’s right with the world. The love she inspires shows up in the film’s on-screen dedication to a woman who was Cuarón’s real-life childhood nanny. She’s doubtless long gone now, but it’s touching that Cuarón remembers so vividly what she brought to his life. (As another real-life story of a boy and a servant, Tony Kushner’s Broadway musical, Caroline, or Change makes a fascinating contrast.)

Cuarón puts his personal stamp on Roma in many artful ways. Aside from directing a first-time lead actress, he wrote, produced, and co-edited this film, also serving as its director of cinematography. Part of the film’s beauty lies in its look: the austere black and white photography, the incisive editing, the sound design. I don’t remember ever seeing a film in which ambient noise played so large a role. Roma transports us to Mexico City in the 1970s, and deep into our own memory banks.

Happy holidays to my readers. God bless us, every one.

Published on December 25, 2018 11:08

December 21, 2018

Fosse with an F

Bob Fosse was, first and foremost, a hoofer, a dancer who combined the razzle-dazzle of Broadway with the slap-and-tickle of old Vaudeville routines. To his own surprise, he rose through the ranks to become a top-flight choreographer and stage director (Sweet Charity, Pippin, Chicago). Along the way, he segued into film projects, winning the 1973 Best Director Oscar for bringing Cabaret to the screen. Cabaret, his second film after the movie adaptation of Sweet Charity, won eight Oscars in all, out of the ten -- including Best Picture -- for which it was nominated. Not bad for a relative newcomer to Hollywood.

Though Fosse was also an award-winner on stage and television (the Liza with a Z concert special), he continued to return to movies. After Cabaret, he turned heads with a non-musical Lenny Bruce biopic, Lenny, starring Dustin Hoffman and Valerie Perrine. His last film, and surely his most controversial, was Star 80, which chronicled the ripped-from-the-headlines death of young Playmate Dorothy Stratten at the hands of her unhinged manager-turned-husband. This 1985 release was notable for Fosse’s insistence on equating himself with Stratten’s killer. Critics, audiences, and members of Stratten’s family reacted with disgust.

My sudden obsession with Bob Fosse comes from my reading of Sam Wasson’s electrifying 2013 biography, simply titled Fosse. Wasson’s hefty but never ponderous tome benefits from the fact that he seems to have interviewed everyone in Fosse’s orbit. He probes Fosse’s backstory – like that period when he was a tapdancing school kid fending off the comic advances of nightclub strippers – to try to understand the complexities of the man’s behavior. There was a nice-boy aspect to Fosse, but it existed side by side with a quality that was outrageously demonic. He sincerely loved his third wife, musical-theatre star Gwen Verdon, and he was a devoted father to their daughter, Nicole. At the same time, he was sleeping with every pretty young female dancer who crossed his path. To meet the challenge of being Bob Fosse on a day-to-day basis, he was also hooked on amphetamines, and was such a constant smoker that sidekicks had to remove smoldering cigarettes from his lips so he wouldn’t get burned.

Throughout his time on earth Bob Fosse was obsessed with death and dying. Despite all the gifts that life had given him, he seemed to feel a need to dance on the edge. This death-obsession was brought forward in spectacular fashion in an autobiographical 1979 film called All That Jazz. It’s remarkable in its willingness to frankly confront Fosse’s own character defects. What we see on screen is the obsessive director/choreographer Joe Gideon (vividly portrayed by Roy Scheider) who slaps himself into action each morning with pills, smokes, and an imperative directed at his mirror-image: “It’s showtime!” There’s the talented, loving wife; there’s the adoring teenaged daughter; there’s the loyal, worried girlfriend played by Ann Reinking in a part reflecting her actual role in Bob Fosse’s life. And there are dancers, scores of them, only too happy to bed the big man if this guarantees them a part in the chorus. There’s the heart attack that Fosse actually suffered, and there’s a mysterious angel-of-death figure (Jessica Lange) who may ultimately be Joe Gideon’s truest love.

Bob Fosse as a dancer can be seen in such 1950s movie musicals as Kiss Me Kate and My Sister Eileen. In 1974 he was coaxed into the Snake’s ominous solo in Stanley Donen’s The Little Prince. It was a role he seemed born to play, and its influence on the later dancing style of Michael Jackson is impossible to overlook.

Published on December 21, 2018 10:00

December 18, 2018

Crimes and Whispers: Louis Malle’s Murmur of the Heart

The French may have a word for it, but I’m not quite sure what it is. Sophisticates among us know there’s a Gallic tradition (in cinema, at least) of an older woman initiating a very young man into sexuality. Mike Nichols actually called upon this tradition in directing Dustin Hoffman in 1967’s The Graduate.Nichols advised Hoffman to keep in mind that in sleeping with his father’s business partner’s wife, Benjamin Braddock was “having an affair that’s almost incestuous.” (Nichols’ satiric point was that Benjamin -- in thrall to a woman close to his mother in age and style -- is still in bed with his parents’ generation, in more ways than one.)

The French may have a word for it, but I’m not quite sure what it is. Sophisticates among us know there’s a Gallic tradition (in cinema, at least) of an older woman initiating a very young man into sexuality. Mike Nichols actually called upon this tradition in directing Dustin Hoffman in 1967’s The Graduate.Nichols advised Hoffman to keep in mind that in sleeping with his father’s business partner’s wife, Benjamin Braddock was “having an affair that’s almost incestuous.” (Nichols’ satiric point was that Benjamin -- in thrall to a woman close to his mother in age and style -- is still in bed with his parents’ generation, in more ways than one.) Benjamin’s fling with Mrs. Robinson may approach incest, but in a French film released four years later, the mother/son incest is the real thing. The film is Louis Malle’s Murmur of the Heart, and (though the movie was restricted to those over 18 even in France) the result is not as salacious as it may sound. I’d always heard that Malle’s movie is semi-autobiographical, which certainly had me worried. Apparently, though, the aspects of Murmur of the Heart that reflect Malle’s own experience are the scenes in which an almost fifteen-year-old boy who loves sexy novels and American jazz is teased unmercifully by two older brothers as he works his way through puberty. (In the film, the brothers take young Laurent to a brothel, and then gleefully burst in on him as he lies in flagrante on top of a motherly hooker).

It's a curious household. The father, a successful gynecologist, is handsome and stern, with a special disdain for his hapless youngest son. The much younger mother – an Italian who was born into poverty – is something of an exhibitionist and something of a rebel. She’s been having an affair with a man who drives a flashy sportscar, and she’s an object of fascination for everyone around her, including the smitten Laurent, with whom she seems to have a specially tender bond.

Circumstances conspire to bring mother and son to a fancy hotel connected with a health spa. Laurent (bursting with hormonal excitement) tries hard to impress himself upon jeunes filles his own age, including one who wears her blonde hair in two girlish ponytails, but this doesn’t work out. His yen for his sexy mom crystalizes when she goes off for a tryst with her lover: the film’s most whimsical and poignant moment comes as, in her absence, he puts on her dressing gown and lovingly arranges her undies, garter belt, and stockings on his bed, as though she herself were there to wear them.

The act of incest, when it comes, is born out of the mother’s unhappiness: she and her lover have parted because she won’t permanently leave her family for him. Reaching out to her sympathetic son as they cuddle together on her bed, she presents the idea as a special one-time event that will be a beautiful and secret memory between them. Mercifully, we don’t see the act itself (hooray for discretion!) but only watch Laurent, in the aftermath, searching the hotel for a willing girl his own age.

The film ends with the reunited family chuckling happily over the evidence that young Laurent has been out tomcatting, but I believe that cheerful note is a false one. Instead I think Malle means us to see trouble ahead for both mother and son, though he leaves it to us to conjure up a sequel. After, of course, we light up a Gauloise and lift our shoulders in a classic French shrug. .

Published on December 18, 2018 10:30

December 14, 2018

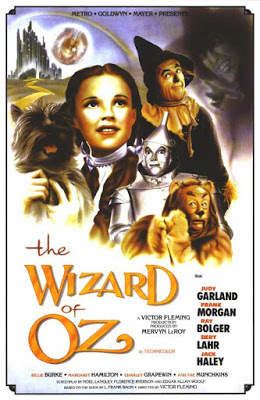

Over the Rainbow—Where L. Frank Baum’s Wizard of Oz Doesn’t Measure Up to the MGM Version

When I was very small, The Wizard of Oz made a triumphant comeback to local movie theatres. With television in its infancy, the return of a family classic like this one to a movie palace near my home was major news. I remember pasting into my scrapbook an advertising photo of Dorothy and Good Witch Glinda. With her poufy dress, cocker-spaniel hair, and helmet-like silver crown, Glinda didn’t seem all that beautiful to me. Still, I was fully prepared to be enchanted by the movie. And of course I was.

It wasn’t until years later that I finally read L. Frank Baum’s 1900 classic, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. And it took many more years—and many more viewings of the 1939 MGM film—before I returned to the novel with my children. I’m all too accustomed to feeling that movies adapted from famous novels lose something of the spirit (and the artistic integrity) of the original. And of course Baum’s brilliantly conceived characters—like the brain-addled Scarecrow, the sentimental Tin Woodman, the Cowardly Lion, and that humbug of a Wizard—will live forever. Still, in reading Baum’s masterwork, I caught myself feeling that its journey from Kansas to the Emerald City was rather plodding and far too moralistic. Baum, the father of four and by all accounts a charming and good-hearted man, was determined to use his writing as a way to improve children’s moral outlook. His great theme is that we all have inside ourselves the ability to achieve our fondest wishes. That’s why he continuously goes back to the Oz friends’ desires—for brains, for a heart, for courage, for home—to remind us that everything is possible if you simply look within.

The editor of The Annotated Wizard of Oz, argues strongly for the merits of Baum’s approach. Michael Patrick Hearn is, needless to say, a serious booster for Baum’s achievement. Where I find it annoying that, on her journey down the Yellow Brick Road, Dorothy keeps stopping to look around for a meal and a place to sleep, Hearn argues that children appreciate the homey details with which Baum grounds his fantasy. He’s also not troubled by the long, meandering section of the book (Fighting Trees! The Dainty China Country!) that follows its most exciting moments: the melting of the Wicked Witch of the West and the unmasking of the Wizard. To Hearn, these long-winded latter segments only serve to reinforce Baum’s moral message.

Even Hearn, though, admits there are areas in which MGM screenwriters have improved upon the original. There’s the beautiful visual image of Glinda saving Dorothy and her friends from the fumes of the deadly poppy field by sending snow. And, more important, there’s the dramatic payoff of the Scarecrow’s fear of fire, which is established early on. In the novel, Dorothy splashes the bucket of water onto the Wicked Witch of the West out of anger, because the witch has swiped one of her precious silver slippers. (They became ruby in the film when the Hollywood moguls decided red shoes would photograph more effectively than silver.) Essentially the book’s Dorothy drenches the witch in a fit of pique, because her prize possessions are being taken from her. See how much more impressively the movie handles this moment: the Wicked Witch, threatening the Scarecrow, hurls a ball of fire in his direction. To save her friend, Dorothy heroically douses him with water, some of which splashes onto the witch who then, as Baum so aptly puts it, melts away before our eyes like brown sugar.

Well, there’s no place like the movies.

Published on December 14, 2018 10:30

December 11, 2018

Widows: Ocean’s Eight in a Minor Key

A small clutch of women, who would seem to have little in common, band together to stage a major heist. Partly they’re after the loot, but this job is also a way of answering the men in their lives, showing that they too have the balls to pull off something big. Does this description sound like Ocean’s Eight? I enjoyed that frothy caper flick, in which Sandra Bullock, Cate Blanchett, and such diverse women as Mindy Kaling, Rihana, and Awkwafina, make off with all the loot at a posh society ball, at least partly in homage to Bullock’s character’s dearly departed brother, Danny Ocean. Widows, though, has much bigger things on its mind.

Widows is the latest from Steve McQueen, whose 12 Years a Slave won the Best Picture Oscar in 2014. To be honest, I wasn’t entirely a fan of that film. Yes, it was skillfully made. But I, for one, felt myself responding to it dutifully, out of a sense of obligation to appreciate a movie all too clearly intended to teach a lesson to the American public. With Widows, no such problem. This is a taut, diverting thriller that makes its socio-political point while never failing our yen to get caught up in a twisty plot. You’re always entertained, but there’s a lot going on beneath the surface.

Widows concerns several women whose husbands have just been killed while trying to hijack millions from a Chicago political campaign. With their private lives in disarray, the new widows are persuaded by one of their number, played by the fierce and yet vulnerable Viola Davis, to carry off the scheme their husbands didn’t live to see through to fruition. By way of flashback glimpses of their former lives, we know that while Davis and her husband (played by Liam Neeson) had a powerful romantic bond, the other women must cling to less happy memories. The devil-may-care spouse of Michelle Rodriguez had a gambling habit that now jeopardizes the future of her barrio dress shop, not to mention the well-being of her children. Newcomer Elizabeth Debicki (whose performance has already garnered accolades) lost an abusive spouse and now finds herself beholden to a chauvinistic suitor who feels he has bought her favors.

Female victimization and female empowerment are important threads throughout the story, but by placing these against a local political campaign McQueen also comments on an all-male world in which both sides—both that of the patrician white alderman and that of the upstart black wannabe—are equally venal (and equally brutal). Some reviewers have found this political backstory less than satisfying, but for me it contributes to the complexity of the world in which Davis and company find themselves. And here’s an example of McQueen’s artistry at work: Davis’s character, who lives well because of her husband’s long criminal past, resides in a sleek modern condo with stark white walls and carefully chosen works of art. In virtually every scene, she’s outfitted in high-style clothing in shades of inky black and crisp white. There’s only one scene in which she wears a Technicolor hue: a bright red sweater. And this scene, which starts out simply enough, turns out to be her character’s essential turning point.

Black, of course, is an appropriate color for a new widow to wear. But I can’t help thinking that McQueen is also quietly commenting on the role of race in the Davis character’s life. The very fact that she’s married to a white man ultimately becomes a part of the unfolding tragedy, in ways that an audience would not at first guess.

Published on December 11, 2018 10:00

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers