Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 73

November 2, 2018

Public Enemy: The Life of Whitey Bulger Comes Full Circle

Not so long ago, my mother and Whitey Bulger had some nice sidewalk chats. It was June, 2011. She was in her nineties, and in the aftermath of a bad fall she was stuck in a rehab facility on 4th Street in Santa Monica. Her caregiver liked to take her out for walks in the neighborhood, and they both enjoyed kibitzing with a white-bearded gentleman who was frequently seen walking his dog. Then one day the street was ablaze with police cars and emergency vehicles. The notorious James “Whitey” Bulger, a Boston mob boss who’d been on the lam for 16 years, had just been caught. The FBI’s Most Wanted Man had been living a quiet life in a Santa Monica condo down the street from where my mom was staying. Obviously—given his background in organized crime—he was no gentleman. But he’d always be my mother’s favorite gangster.

Now both Mom and Whitey Bulger are gone. She passed on in 2014, at the ripe old age of 96. He lived until the day before Halloween: October 30, 2018. When I first read that he’d died behind bars, I figured old age had caught up with him. Yes, he needed a wheelchair, but his end was apparently not as uneventful as that. When he was found unresponsive in his cell at the high-security prison in West Virginia to which he’d just been transferred, authorities immediately began investigating. Now the word is that he’d been beaten to death by a fellow inmate, who just happens to be a Mafia hitman.

More to come, I’m sure.

And this story will of course once again ramp up our fascination with the life (and death) of mobsters. Bulger himself inspired more than one movie and television drama. TV series ranging from Law and Order to Ray Donovan have included characters based on Bulger. In Martin Scorsese’s Oscar-winning 2006 film, The Departed, Jack Nicholson plays a colorful Bulger-like mob boss. The film Black Mass, released in 2015, is based on a 2001 non-fiction book, Black Mass: The True Story of an Unholy Alliance Between the FBI and the Irish Mob, by Dick Lehr and Gerard O'Neill. To quote Wikipedia, “The film chronicles Bulger's years as an FBI informant, and his manipulation of his FBI handler as a means to eradicate his rivals for control of the Boston underworld, the Italian Mafia.” A heavily made-up Johnny Depp nabbed a Screen Actors Guild award for his lead performance.

Let’s face it: we love on-screen gangsters. Think of Marlon Brando as Don Vito Corleone in Francis Ford Coppola’s Godfather films. Think of Scorsese over and over, probably hitting his peak with 1990’s Goodfellas. Now think back in time to the glory days of James Cagney and Edward G. Robinson. Cagney’s The Public Enemy and Robinson’s Little Caesar, both 1931, helped pave the way for bigger, bolder films about vengeful hoodlums who somehow won the audience’s affection. They also paved the way for the enforcement of the Production Code, which tried (but failed) to staunch the public’s yen for bad guys who were blood-thirsty but appealing.

Gangster stories are also fairly economical to film, which is why low-budget moviemakers of the Roger Corman ilk often put them on their production schedules. They mostly require prop weapons, lots of blanks, and gallons of fake blood. Corman made I Mobster, Machine-Gun Kelly (with the young Charles Bronson), and lots of others. I personally worked on Capone (starring Ben Gazzara) and—much later—Dillinger and Capone (with Martin Sheen and F. Murray Abraham). In Hollywood, at least, bad guys make good.

Published on November 02, 2018 10:53

October 30, 2018

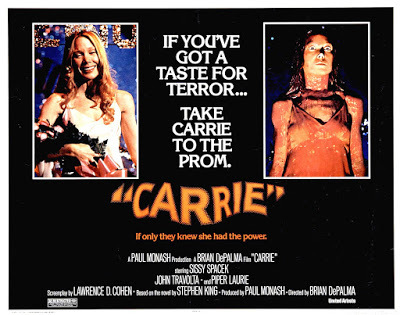

The “Carrie” Remake: Horror Plus Time Doesn’t Always Equal Hollywood Magic

Where horror movies are concerned, what goes around certainly comes around. Witness the success of the updated Halloween at this week’s box office. And Dario Argento’s 1977 balletic creepfest, Suspiria, has just returned, now helmed by Luca Guadagnino of Call Me By Your Name fame. I haven’t seen these yet, but I did recently catch up with the 2013 remake of a horror classic, Brian De Palma’s 1976 screen adaptation of Carrie.

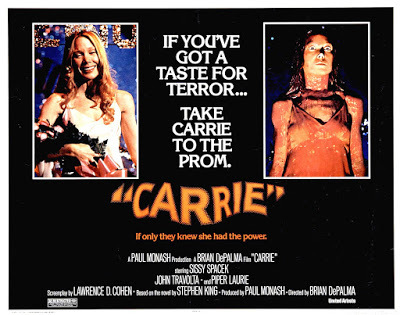

Carrie, of course, was the first Stephen King novel to make it to the screen, and it remains one of the few adaptations of his writing to win his praise. a wonderful little anthology called Double Features: Big Ideas in Film , published last year by the Great Books Foundation, reprints King’s seminal 1981 essay, “Why We Crave Horror Movies.” King’s essay, which covers flicks ranging from Roger Corman’s The Pit and the Pendulum to Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, speaks admiringly about how De Palma’s approach to the story of Carrie’s frightful coming of age “is lighter and more deft than my own—and a great deal more artistic.” What’s key for King is that “when the horror movies wear their various sociopolitical hats—the B picture as tabloid editorial—they often serve as an extraordinarily accurate barometer of those things that trouble the night thoughts of a whole society.” When he wrote Carrie back in 1973, he was musing not only about a lonely young girl but also about “how women find their own channels of power and what men fear about women and women’s sexuality.” His lurid tale of Carrie coming into her own was “in its more adult implications, an uneasy masculine shrinking from a future of female equality.” To King, this subtle undercurrent in his own work was brought dramatically forward in De Palma’s screen version, which captured (at a time when the Women’s Movement was picking up steam) a culture’s need to grapple with changing gender dynamics.

I’m not sure whether, when I first saw Sissy Spacek take bloody revenge on her high school world in Carrie, I picked up on the underlying layer of meaning that King describes. I do know, though, that this is one flick that can chill to the marrow anyone who’s ever felt out of place at a high school dance. Or comes from a wacky family background or otherwise doesn’t belong among the cool kids but would love to be welcomed in. The film version of Carrie (anchored by the riveting performances of Spacek and Piper Laurie as her religious-crackpot mother) is so indelible that I can’t imagine why anyone would feel the need to remake it. So of course they did.

The 2013 reboot of Carrie is directed by Kimberley Peirce, who had made a notable debut with the gender-bending Boys Don’t Cry in 1999. It’s well cast, with the talented young Chloë Grace Moretz in the title role and Julianne Moore playing her mother from Hell. There are a few stabs at modernizing the story, with Carrie’s traumatic locker-room humiliation videotaped on her classmates’ cellphones and spread through the teen world via social media. Otherwise, I don’t see many significant changes from the De Palma version. I can’t help feeling that Sissy Spacek seemed eerier, more genuinely possessed, than Moretz, whose more conventional prettiness also makes her less physically distinctive than her predecessor in the role. And nothing can rival the perversity of the original ending, with Mrs. White’s almost orgiastic acceptance of her suffering, some bizarrely inverted near-Christian iconography, and yes! that final scare. Yikes!

And of course Happy Haunting this Halloween!

Published on October 30, 2018 12:37

“Carrie”: Horror Plus Time Doesn’t Always Equal Hollywood Magic

Where horror movies are concerned, what goes around certainly comes around. Witness the success of the updated Halloween at this week’s box office. And Dario Argento’s 1977 balletic creepfest, Suspiria, has just returned, now helmed by Luca Guadagnino of Call Me By Your Name fame. I haven’t seen these yet, but I did recently catch up with the 2013 remake of a horror classic, Brian De Palma’s 1976 screen adaptation of Carrie.

Carrie, of course, was the first Stephen King novel to make it to the screen, and it remains one of the few adaptations of his writing to win his praise. a wonderful little anthology called Double Features: Big Ideas in Film , published last year by the Great Books Foundation, reprints King’s seminal 1981 essay, “Why We Crave Horror Movies.” King’s essay, which covers flicks ranging from Roger Corman’s The Pit and the Pendulum to Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, speaks admiringly about how De Palma’s approach to the story of Carrie’s frightful coming of age “is lighter and more deft than my own—and a great deal more artistic.” What’s key for King is that “when the horror movies wear their various sociopolitical hats—the B picture as tabloid editorial—they often serve as an extraordinarily accurate barometer of those things that trouble the night thoughts of a whole society.” When he wrote Carrie back in 1973, he was musing not only about a lonely young girl but also about “how women find their own channels of power and what men fear about women and women’s sexuality.” His lurid tale of Carrie coming into her own was “in its more adult implications, an uneasy masculine shrinking from a future of female equality.” To King, this subtle undercurrent in his own work was brought dramatically forward in De Palma’s screen version, which captured (at a time when the Women’s Movement was picking up steam) a culture’s need to grapple with changing gender dynamics.

I’m not sure whether, when I first saw Sissy Spacek take bloody revenge on her high school world in Carrie, I picked up on the underlying layer of meaning that King describes. I do know, though, that this is one flick that can chill to the marrow anyone who’s ever felt out of place at a high school dance. Or comes from a wacky family background or otherwise doesn’t belong among the cool kids but would love to be welcomed in. The film version of Carrie (anchored by the riveting performances of Spacek and Piper Laurie as her religious-crackpot mother) is so indelible that I can’t imagine why anyone would feel the need to remake it. So of course they did.

The 2013 reboot of Carrie is directed by Kimberley Peirce, who had made a notable debut with the gender-bending Boys Don’t Cry in 1999. It’s well cast, with the talented young Chloë Grace Moretz in the title role and Julianne Moore playing her mother from Hell. There are a few stabs at modernizing the story, with Carrie’s traumatic locker-room humiliation videotaped on her classmates’ cellphones and spread through the teen world via social media. Otherwise, I don’t see many significant changes from the De Palma version. I can’t help feeling that Sissy Spacek seemed eerier, more genuinely possessed, than Moretz, whose more conventional prettiness also makes her less physically distinctive than her predecessor in the role. And nothing can rival the perversity of the original ending, with Mrs. White’s almost orgiastic acceptance of her suffering, some bizarrely inverted near-Christian iconography, and yes! that final scare. Yikes!

And of course Happy Haunting this Halloween!

Published on October 30, 2018 12:37

October 25, 2018

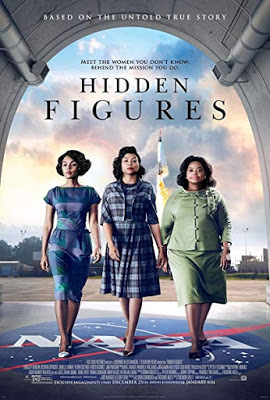

How the Figures in “Hidden Figures” Came To Life

In 2016, Hidden Figures was a surprise box office hit. This story of three smart black women who contributed mightily to NASA’s early triumphs while battling segregation at Virginia’s Langley Research Center proved so irresistible that the film was nominated for a Best Picture Oscar. There were also nominations for co-star Octavia Spencer and for screenwriters Allison Schroeder and Theodore Melfi, who had adapted historian Margot Lee Shetterly’s 2016 book of the same name. The writers didn’t win their Oscar (that honor went to Barry Jenkins for Moonlight). But they were certainly deserving. Now that I’ve read Shetterly’s book, I realize that this screenplay is a textbook example of how to turn a serious work of history into a living, breathing film.

Not that I have any complaints about Shetterly’s considerable achievement. Her book, subtitled The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space Race, is a serious chronicle, one that covers segregation in Hampton, Virginia from World War II onward, while also providing a full account of the changing workplace at Langley. At the same time, it introduces some fascinating women who bucked racial prejudice and social conditioning to succeed as “computers,” dedicating their mathematical skills to the Langley engineers’ high-level projects, though expecting little in the way of personal reward. Because Shetterly is revealing a slice of history that previously was scarcely known, she also goes far afield, covering (for instance) the challenges faced by black male engineers who sought work at Langley as well as what happened to the first black candidate to join the astronaut corps.

But the screenwriters know that history lessons don’t always make for good cinema. A quick glance at their screenplay reveals how, from the start, they make sure that Shetterly’s three main “hidden figures” are front and center. Without being untrue to the basic personalities of Dorothy Vaughan, Katherine Johnson, and Mary Jackson (as revealed in Shetterly’s intense researched book), the screenwriters find colorful ways to dramatize the challenges faced by each woman.

With three strong actresses—Octavia Spencer, Taraji P. Henson, and Jannelle Monáe—in the central roles, each must be given something vivid to do. The film kicks off with the trio carpooling to Langley, only to face a broken-down engine and the attentions of a skeptical white policeman. Monáe, as the spirited Mary Jackson, boldly sasses the cop, while the super-competent Spencer (as Vaughan) coaxes the car back into service. It’s a clever intro to the three, though Shetterly’s book mentions that the real Vaughan never learned to drive.

Shetterly also notes how the “colored” computers at Langley struggled to find restrooms they were permitted to use. In the screenplay this becomes a sequence—both hilarious and poignant—in which Henson (as the redoubtable Johnson) races against a deadline to finish the stack of calculations to which she’s been assigned while also desperately seeking a place to answer nature’s call. The sequence ends dramatically with her new boss, played by Kevin Costner, destroying the sign that had made the nearby ladies’ room exclusive to whiteemployees.

The script also adds a few snippy villains (played by Jim Parsons and Kirsten Dunst) for our heroines to butt their heads against. And the climactic contribution of Katharine Johnson to John Glenn’s Apollo mission is played out for all it’s worth. Yes, Glenn did actually say he’d trust Johnson’s calculations before he’d trust a computer, but the detour he makes on the tarmac to shake the hands of the black computers is one more lovely fiction that adds to the power of this film.

Published on October 25, 2018 11:25

October 23, 2018

The Shadow of a Smile in Big Sur

Big Sur is a heavenly spot on the California coast, a place of rugged rocks, crashing waves, and twisted cypress trees. It has always had an artistic soul, and a penchant for welcoming hippies and mystics. Naturally, the movie-making community is not immune to its charms. On a recent trip to Big Sur, which included wine, burgers, and a brilliant sunset at the legendary Nepenthe, I couldn’t help associating the natural beauty of the locale with memories of one of the worst movies I ever saw. Oddly, I watched it at Radio City Music Hall on my very first visit to New York City. The year was 1965, and the film was The Sandpiper. It starred the then-notorious Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, playing out their personal love affair in glorious Technicolor.

Here’s the plot, such as it is: Elizabeth is a free-spirited artist with a beach shack and an out-of-wedlock young son. Richard is a starchy Episcopal priest who runs a boarding school in Monterey. Some run-ins with the law mandate that her son be enrolled in his school. Sparks fly, despite the differences in belief and lifestyle, and soon Burton is pining as only Richard Burton can pine. One major problem is that he’s already married, to the saintly (of course) Eva Marie Saint. What to do?

The central act of the movie consists of lots of scenery, lots of pining among the pines, and some symbolic claptrap involving a sandpiper with a broken wing. There’s also a scene immortalized in a Mad Magazine parody I remember from back in the day: Zaftig Liz is depicted by Mad artist Mort Drucker as shrinking a pair of women’s slacks until they are doll-sized, then putting them on and walking around in them. Taylor may have had a beautiful face in 1965, but figure-wise she was hardly a woodland sylph.

Of course this sort of movie from the mid-Sixties had to end on a sad, poignant note. In this it was helped immeasurably by the film’s secret asset, its soupy, string-heavy score. The Sandpiper was nominated for, and won, a single Oscar, for the hit song, “The Shadow of Your Smile.” It was composed by Johnny Mandel, best known today for his evocative “Suicide is Painless” theme from M*A*S*H.

Looking at The Sandpiper’s credits now, it’s depressing to see all the major showbiz names involved in this turkey. The MGM release, starring Hollywood’s most famous (and well-paid) romantic couple, was given the full-blown Golden Age treatment. The director was Vincente Minnelli, who was much better served by his work on big, bright musicals like Meet Me in St. Louis, An American in Paris, and Gigi, but also helmed his share of powerful dramas. Producer Martin Ransohoff had a distinguished career, and the estimable Dalton Trumbo apparently had a hand in the script.

Despite all my snarky comments, lovers of the lugubrious might find themselves enjoying The Sandpiper. My family and I were actually at Radio City Music Hall to see the famous Rockettes do their pre-show high kicks. When the film came on, we decided to watch for a bit—and then couldn’t tear ourselves away. A Noel Coward character once quipped, “Strange how potent cheap music is." The same thing goes for lousy movies: if they’re really, really bad, they’re sometimes irresistible.

Of course, someone who wants a completely different view of Big Sur should check out a Roger Corman psychedelic classic from 1967, The Trip.Big Sur was also the site of Roger’s famous personal experiment with LSD. But that’s a story for another day. .

Published on October 23, 2018 16:20

October 19, 2018

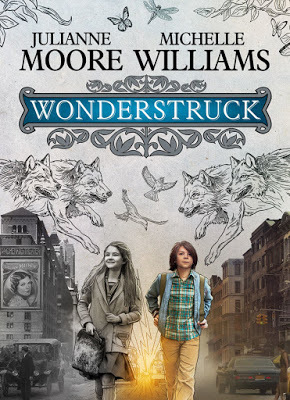

Wondering about the Sounds of Silence in “Wonderstruck”

I must say: I wasn’t entirely struck by Wonderstruck. I’ve admired a lot of the work of director Todd Haynes, whose sensitivity and indie sensibilities appeal to me greatly. And I knew the screenplay was written by Brian Selznick, adapting his own quirky juvenile novel as he had done for the spectacular Hugo. Add in a performance by Haynes favorite Julianne Moore, as well as a suitably eclectic score by the talented Carter Burwell, and you would seem to have something pretty special indeed.

Wonderstruck is certainly unique in its conception. It tells what seem to be two separate stories from two separate eras. One, set in 1977, involves a twelve-year-old Minnesota boy, grieving the loss of his mother and his hearing, who travels to New York City in search of the father he’s never known. The other, taking place fifty years earlier, features a young deaf girl who runs away from her affluent Hoboken home to seek out a glamorous Hollywood star about to open on Broadway.

The stories collide—in their fashion—at the New York Museum of Natural History, where an historic exhibit of old curiosity cabinets (the forerunners of today’s museums) creates some creative linkage between them. But it’s not until the film’s final moments that we understand the full connection between the two young lives being explored. Haynes shot the 1977 scenes in color and the 1927 scenes in classic black-&-white, moving gracefully between the two. So much to admire, but I admit I for one often got restless, especially where the young boy’s tale of woe was concerned.

But that 1927 storyline had me riveted. Partly that was thanks to the dynamic, though non-speaking, performance of Millicent Simmonds, appearing in her first film. Simmonds, who has been deaf since infancy, has an open, appealing face that beautifully captures the emotions of her character. One particularly poignant moment: leaving a movie theatre where she has just thrilled to the dramatic escapades of silent star Lillian Mayhew, she pauses wistfully beneath the marquee which proclaims that the theatre will soon be closed for the installation of a sound system, so that future audiences can enjoy talkies. It’s a moment that instantly captures the isolation of a deaf girl who has never been exposed to American Sign Language. Kudos to director Haynes for insisting that an actual deaf child play this role.

The first time I paid attention to the plight of the deaf was watching the stage version of Mark Medoff’s Children of a Lesser God. In 1986 the play became a movie, and its hearing-impaired star, Marlee Matlin, ultimately won a Best Actress Oscar for her role as an angry young deaf woman who refuses to attempt verbal speech. This was her first film, but the Oscar wasn’t granted to her solely out of sympathy for her affliction. I’m happy to report that she’s had a lot of film and television roles since, mostly playing women who just happen to be deaf but also enjoy many other distinctive character traits.

Here’s hoping the incandescent young Millicent Simmonds will have an equally fulfilling career trajectory. This year she was featured as the hearing-impaired daughter who is central to John Krasinksi’s effective thriller, A Quiet Place, and other roles are on tap. A kid from small-town Utah who was dazzled by her first visit to Manhattan, Millie is loving the excitement. So far she’s exuberant and fearless about the new direction her life is taking: “I want to be an actor to show deaf people can do it. You're not too young to dream big!”

Published on October 19, 2018 10:00

October 16, 2018

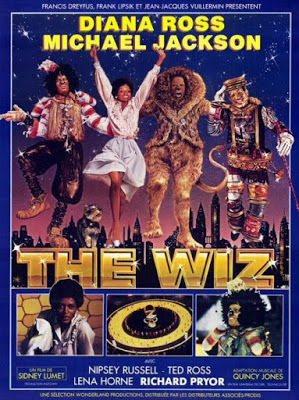

Easing On Down the Road with The Wiz

In early 1975, while blaxploitation flicks like Shaft and Superfly were still scoring on multiplex screens, Broadway welcomed a musical version of the classic Wizard of Oz that introduced black vernacular, pop music, and an entirely black cast. The show, which was called The Wiz, played to packed houses until 1979. At the annual Tony Awards festivities, it collected seven statuettes, including Best Musical Score and Best Musical. For the late Geoffrey Holder, husband of my first dance teacher, Carmen de Lavallade, it was definitely a career highpoint. The multitalented Holder won a Tony for directing the show, and a second for designing its flamboyant costumes. When his name was called, he literally danced up to the stage in a wonderful display of showmanship.

A hit of this magnitude of course captured the imagination of Hollywood. Transferring a fantasy from stage to screen is always a challenge, but the filmmakers behind The Wiz made some choices that definitely added to their difficulties. The Dorothy on stage in The Wiz, like that in the classic Judy Garland film adapted from the L. Frank Baum novel in 1939, is played as an innocent young girl. But the Hollywood team doubtless felt it needed a star performer, which is why it gave the role to Diana Ross, age thirty-four. A very game Ross could indeed look super-skinny and helpless, but she couldn’t convince as an adolescent. That’s why her part was transformed into that of a rather agoraphobic spinster kindergarten teacher who works hard on behalf of her extensive Harlem family but is cut off by her own fears from enjoying the world outside her door. The team behind Ross and company today seems unlikely. The screenwriter was Joel Schumacher, not yet a director of tough dramas. The director was the great Sidney Lumet, best known for films (like The Pawnbroker, Serpico, and Dog Day Afternoon) that captured a sense of urban squalor.

Perhaps because of Lumet’s experience on the streets of New York City, this cinematic version of The Wiz dropped the traditional Kansas setting of the opening scene in favor of a gritty urban Harlem streetscape. Characters descend into a spooky but fantastically appointed subway, and the Cowardly Lion (Ted Ross, who’d also won a Tony for this role) starts off as one of the lions in front of the New York Public Library. Other characters are played by Hollywood royalty, including Richard Pryor as the Wizard himself, Lena Horne (Lumet’s mother-in-law) who gets to sing a corny ballad as Good Witch Glinda, and none other than Michael Jackson, playing his first movie role as the Scarecrow. Watching this film for the first time recently, I admired the lively sets and costumes (the film earned four Oscar nominations in technical categories), but disliked the way the lugubrious story advanced at a crawl, milking every opportunity to be sentimental.

But the recent trend for “live” musicals on TV gave me a chance to relive the spunk and spirit of the stage show. The 2015 broadcast was chockful of stars (Common, David Alan Grier, Mary J. Blige as an appropriate hateful Wicked Witch of the West, aka Evillene), but an actual teenager, Shanice Williams, was the glue that held it all together. Perhaps some of the excitement came from the adrenaline rush as cast and crew all joined hands to work at achieving theatrical perfection. I also sensed freshened dialogue, a sharpened storyline, and less easy sentimentality. Sorry, Diana Ross – you’re a singer like no other, but I’d rather not ease on down the road again with you anytime soon.

Published on October 16, 2018 10:00

October 12, 2018

The Old Man & The Graduate

Robert Redford turns on the charm full blast in his latest (and possibly his last) film, The Old Man & The Gun. Though he’s now a weather-beaten eighty-two years old, he capers nimbly through a picaresque movie in which he robs banks, romances a glowing Sissy Spacek, and makes a great case for Senior Citizen Power. In the Hollywood spotlight for fifty years, Redford has proved himself as an actor, a producer, and an Oscar-winning director (for 1980’s Ordinary People). He’s also been active in political and environmental causes, and founded the Sundance Institute (along with the famous Sundance Film Festival) to give independent films and filmmakers a leg up. The Old Man & The Gun features at one point vintage photos of the young Redford, including an actual still of him on the lam in Arthur Penn’s 1966 thriller, The Chase. Those photos remind us—as though we needed reminding—of how astoundingly handsome he once was.

Yes, Redford has done a lot. But he did not get a chance to star for Mike Nichols as Benjamin Braddock in The Graduate. Even though he came close. Here, based on the research I did for my Seduced by Mrs. Robinson, is the full story:

In 1963, a young producer named Lawrence Turman read a novel by a recent college graduate named Charles Webb. Turman learned about Webb’s not-very-successful novel in the New York Times. The Times reviewer had some complaints about the novel, but also said that Webb had, in Benjamin Braddock, “created a character whose blunders and follies just might become as widely discussed as those of J. D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield.” These were magic words: everyone in Hollywood longed to film something on the order of Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Having bought the movie rights to Webb’s The Graduate, Turman approached Mike Nichols, well known for his sketch comedy act with Elaine May. Nichols had never directed a movie, but he’d just had a major Broadway hit directing an early Neil Simon laughfest, Barefoot in the Park, about a pair of newlyweds adjusting to life in New York City. The young husband was played by Robert Redford.

In 1967, as Mike Nichols was preparing to film The Graduate, he naturally thought of the handsome, intelligent stage actor. By this point, Redford was making his mark on Hollywood, with featured roles in films like The Chase and Inside Daisy Clover. He wanted to play the hapless Benjamin Braddock, and Mike Nichols wanted to hire him. The legendary story, which has circulated for fifty years, is that Nichols, finally concluding that Redford wasn’t right for the role, asked the actor, “What was the last time you struck out with a girl?” RespondedRedford, totally nonplussed, “What do you mean?”

Larry Turman told me the reality was just a bit different. He’d always felt that Benjamin Braddock wouldn’t be funny unless he was a lovable bumbler, age twenty-one going on sixteen. Turman had a hunch that Redford, talented though he was, would project a screen image that was too suave and sophisticated for the character. Nonetheless, Redford was one of six actors who screen-tested for the role, along with Tony Bill, Charles Grodin, and a nervous young man named Dustin Hoffman. Both Turman and Nichols were rooting for Redford, but both finally agreed he was just not their idea of what Benjamin should be. Redford’s day, though, would soon come. Two years later, he starred with Paul Newman in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, perfecting his portrayal of a gunslinging rogue. And a star was born.

Published on October 12, 2018 11:03

October 9, 2018

The Late Scott Wilson – This Time It’s Real

That's Robert Blake at left, Scott on the right

That's Robert Blake at left, Scott on the right Scott Wilson is dead. Admittedly, it’s hardly the first time he has died. In 1967, he was hanged in the courtyard of the Kansas State Penitentiary for having committed multiple brutal murders. In 2003 he suffered a different fate, at the hands of Florida serial killer Aileen Wuornos. And he was unlucky enough to get fatally mixed up with zombies in TV’s The Walking Dead. Wilson was of course an actor who emerged unscathed from all of his dealings with mortality in films like Monster and In Cold Blood. Now, alas, he has succumbed to leukemia for real, at age 76.

I met Scott Wilson when I was researching the films of 1967. I was thrilled to speak with him, because he’d appeared in two of the best, In the Heat of the Night (he played fugitive Harvey Oberst, who is cleared of a murder rap by Sidney Poitier’s detective Tibbs) and In Cold Blood. I think he was flattered to have the start of his career examined so closely. We sat in the dim, cozy living room of his West Hollywood duplex, sipping tea and munching cookies graciously served by his wife Heavenly, a lovely woman who fully measured up to her challenging name. As my tape recorder slowly turned, Scott reminisced about landing the role of Harvey, who starts out as a racist but ends up becoming a true believer in Mister Tibbs’ smarts.

It helped that he was a Southerner by birth, from Atlanta. When he discovered acting as a young man, he spent five years learning every aspect of the craft, never actually expecting to earn a living on stage or screen. Auditioning for the role of Harvey, he knew he’d have to do a lot of cross-country running: his character has committed a robbery and is fleeing through the Mississippi countryside to escape the long arm of the law. Fortunately, he was then earning his keep as a valet parker, sprinting up Hollywood hills to retrieve the cars of restaurant patrons, and so he could handle the physical challenges of his part with ease.

Thanks to Poitier and Quincy Jones, Scott was encouraged to try out for the leading role of a feckless killer in the screen version of Truman Capote’s true-crime thriller, In Cold Blood. He physically resembled the real Dick Hickock (who committed the killings along with Perry Smith), and he possessed a hearty laugh that bubbled out of him at unexpected moments, lending an eerie quality to the most mundane conversations. I was spooked by that laugh, even in his comfortable living room, especially when he played me an audition tape (from the old stage chiller, Night Must Fall) that he used to nab the Hickock role.

Columbia Pictures originally wanted major stars to play the two young killers. But Scott explained that director Richard Brooks insisted on unknowns “so there would be nothing to blemish the audience’s reaction to the killers; they could identify with them as killers instead of actors.” This helped catapult a screen novice into a leading role, but it also had its downside: Brooks made little attempt to tout his unknowns, Scott and Robert Blake, as actors. Result: they missed out on award recognition they richly deserved.

Still, Scott wasn’t in it for the accolades. He told me, “I didn’t aspire to walk the red carpets. I didn’t aspire to the accouterments of being an actor. It’s what surrounds being an actor. Once I found acting, I said, this is what I want to do. I was really never interested in being a star.”

Hail, and farewell.

Published on October 09, 2018 12:10

October 5, 2018

Dishing Out The Devil’s Candy: How "The Bonfire of the Vanities" Became a Big-Screen Flop

One of the biggest questions I had about The Devil’s Candy: The Anatomy of a Hollywood Fiasco wasn’t answered until I got to the final pages of the 2002 re-issue. In reading about the 1990 screen adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s whizbang novel, The Bonfire of the Vanities, I’d learned seemingly everything there was to know on how a potential Hollywood blockbuster was conceived, written, cast, directed, produced, and marketed. No detail seemed too small to escape the notice of journalist Julie Salamon as she chronicled how the film’s budget soared to what was then an unheard-of amount, just shy of $50 million, and how (despite major stars, spectacular sets, an A-list director, and the faith of a legendary studio) public reaction had doomed the picture to be remembered as the Ishtar of its era. How did she know so much?

Since I’m a former filmmaker and an author of several books on the ways of Hollywood, I of course wanted more info about Salamon’s research. It wasn’t until, on p. 433, I arrived at an Author’s Note that I got my answer. Back in 1991, Salamon was a film critic for the Wall Street Journal. After being on the job for more than a a decade, she decided she’d like to follow a big-league Hollywood production from beginning to end. Lillian Ross of The New Yorker had accomplished the same feat on John Huston’s The Red Badge of Courage¸ ultimately publishing a book titled Picture, but that was back in 1952. Salamon was fortunate that Brian De Palma, a director known for his willingness to take risks, accepted her presence on his sets and in his conference rooms without pre-conditions. Armed with notebooks and a tape recorder, she watched everything from opening shot to wrap, and freely conducted interviews with willing members of the cast and crew.

For Salamon as a reporter there were risks and rewards aplenty. She got to know studio execs, and chatted with superstars like Tom Hanks and Melanie Griffith. But in the aftermath of her book’s publication, she was the subject of highly vicious comments by an irascible Bruce Willis, who called her a parasite and much much worse, making crude remarks in a national magazine about her breath and at one point suggesting that she blow her brains out. (A journalist’s lot, then and now, is not a happy one.)

One message of The Devil’s Candy is that Hollywood success is a crap shoot. Though Salamon was well aware of budget overruns, and knew that the Wolfe novel was controversial source material, she never saw herself as chronicling a disaster in the making. One of the most endearing portraits in her book is that of Eric Schwab, a young second unit director committed to dazzling his mentor, De Palma, with a spectacular shot. When the original plan for an electrifying New York City night montage was scrapped, Schwab became determined that his coverage of a Concorde landing at JFK would make it into the film. Calling upon every resource at his disposal, he pulled off a thrilling image of an Air France plane floating out of an orange sky. Yes, it made the final cut, though cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond tried to take credit for Schwab’s achievement. Schwab’s efforts brought him to the attention of some Hollywood honchos, but Salamon’s ten-years-later epilogue tells us that as of 2001 he was still hustling to make movies of his own, falling back on second-unit work on De Palma films like Mission Impossible in order to make ends meet. What price Hollywood, anyway?

Published on October 05, 2018 10:59

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers