Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 78

May 15, 2018

Beverly Hills Ballot-Box Ballyhoo

Growing up in the West Los Angeles subdivision known as Beverlywood, I developed a certain perspective on Beverly Hills. (For the record, I was called Beverly long before I moved into the area, though I’m sure my parents were not ignorant of the name’s associations with ritzy SoCal enclaves.) As an L.A. girl who lived just a few short blocks from the Beverly Hills border, I developed mixed emotions about the little city to the north. Yes, it was fun to stroll up Beverwil Drive and find myself among charming cafes and chic boutiques. I remember star-sightings over lunch at the Hamburger Hamlet and yummy ice cream cones at Wil Wright’s.

On the other hand, kids like me had to deal with the snobbery of our north-of-the-border peers. They told us in no uncertain terms that their public schools were much better than ours. I was informed that the A’s I earned at LA.’s Canfield Elementary School would be mere B’s and C’s in Beverly Hills, since their standards were so much higher. Those memories have shaped my feelings about Beverly Hills ever since.

Still, I liked seeing Donald O’Connor pushing his cart in the supermarket, Zsa Zsa Gabor nibbling on pastry at Blum’s, and Sammy Davis Jr. driving his Excalibur through the tree-lined streets of Beverly Hills. And I remember the day in 1960 the city celebrated the installation of an odd little sculpture at the intersection of Olympic Blvd. and Beverly Drive. This so-called Celluloid Monument honors Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, Rudolph Valentino, Will Rogers, and other Hollywood personalities who fought to preserve the autonomy of Beverly Hills when it was on the brink of being swallowed up by the city of Los Angeles.

One big issue at the time was the allocation of drinking water, always a major concern in dusty, drought-prone Southern California. Another, of course, was power politics. Nancie Clare’s engaging The Battle for Beverly Hills lays it all out for us, making clear why the survival of one small California city has lessons for us today. Her subtitle, “A City’s Independence and the Birth of Celebrity Politics,” points to the impact of Hollywood stardom—something brand-new when the annexation vote was taken back in 1923—on the general public. Clare’s book told me a lot about the evolution of Southern California as a result of the burgeoning film industry. In particular, it clued me in to the power wielded by Mary Pickford, a woman determined to make her own way, both artistically and financially. Pickford fought hard to preserve the new little city as a garden spot populated by the wealthy and the famous. It was she who enlisted noteworthy actor and director friends to go door to door, appealing to Beverly Hills residents to vote against being annexed by Los Angeles. (The nearby city of Hollywood had knuckled under to its much-bigger neighbor back in 1910.)

Pickford’s posse—which also included cowboy star Tom Mix, funny-man Harold Lloyd, and Fred Niblo, director of the original Ben-Hur—liked the privacy that living in Beverly Hills afforded. Clare explains that matinee idol Conrad Nagel, another of Pickford’s eight campaigners, would one day even “head up a movement to build a wall around Beverly Hills to keep the outer world at bay.” This talk of a wall can’t fail to remind us of other public figures with showbiz roots who have used their fame as a political stepping stone. There’s Ronald Reagan, of course, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, and a certain reality-show host who has parlayed his celebrity all the way to the White House.

Published on May 15, 2018 13:45

May 11, 2018

Heaven is “Heaven is a Traffic Jam On The 405”

Everyone who’s spent time in L.A. knows that the 405 Freeway (formerly known as the San Diego Freeway) is a necessary evil. If you take it north from the urban center, it lurches through Sepulveda Pass—where the Getty Center and other cultural venues await—and descends into the smoggy suburban sprawl of the San Fernando Valley before moving toward the hinterlands. If you take it going south, it elbows its way past shopping malls, a cemetery, some auto dealerships, and Los Angeles International Airport, then trudges toward Long Beach and (after a long while) San Diego. Whatever the time of day, it’s generally socked in with rush-hour traffic. We need it, but that doesn’t mean we like it.

Except, perhaps, for Mindy Alper. Remarkably, she finds being stuck in L.A. traffic restful. To make sense of this oddball perspective, it helps to understand that Mindy, now age 56, has an acute mental disorder that requires her to gulp down dozens of pills each day. At times she’s been committed to mental institutions; she has undergone shock therapy and spent one entire decade without speaking. It sounds as though she’s depressing to be around, but this is far from true. Late-in-life documentary filmmaker Frank Stiefel (a former executive in charge of TV commercials) made a short film about Mindy that toured the festival circuit in 2017, to loud acclaim. Earlier this year, Heaven is a Traffic Jam on the 405 (its title comes from one of Mindy’s on-camera musings) was awarded the Oscar for Best Documentary Short Subject. I was lucky enough to see it at a screening at which both Frank and Mindy were present. It’s clear that Mindy’s deep, familial trust in Frank made this enchanting film possible. In person, she’s articulate and funny. And, as we learn from the film, an extraordinary talent.

Frank Stiefel found out about Mindy when his wife enrolled in an art workshop led by a particularly sensitive and encouraging instructor. Frank’s wife would come home with stories about a most unusual woman, someone who didn’t socialize with the others but displayed remarkable artistic abilities in a number of media. She could draw sharp, funny, highly incisive sketches that hinted at the turmoil within her. She also showed a gift for giant papier-mȃché sculptures that capture the souls of the people in her life. As a human being she continued (and still continues) to face major demons, but her artwork was good enough to earn her a showing at the highly-respected Rosamund Felsen Gallery in 2007. Felsen still represents her today.

Stiefel’s film gently probes the mysteries of Alper’s formative years. Her mother (still alive and interviewed on-camera) was loving, though somewhat baffled by her difficult daughter. Her father, who appears in Mindy’s drawings as a powerful, terrifying figure capable of sucking out her essence, seems never to have accepted what she was going through. (The film allows the viewer to wonder how much he was responsible for her downward spiral, but by now she has found a path to forgiveness.) Vital figures like supportive teachers and therapists loom large in her art, as in her life, represented by huge three-dimensional portrait busts that are awe-inspiring in their complexity. Oscar-nominated documentaries tend to be about grim subjects like drug abuse, racism, and war. The wonderful thing about Heaven is a Traffic Jam On The 405 is that it shows that even the gravest physical and psychological problems can be overcome, thanks to a combination of skill, will, and love. And, of course, the healing power of art.

Here is a link to the trailer from Frank Stiefel's film.

And here's a photo of Mindy from a recent L.A. Times profile

And here's a photo of Mindy from a recent L.A. Times profile

Published on May 11, 2018 13:39

May 8, 2018

A “Working Girl” in the Era of #MeToo

The 1988 film Working Girl begins with a huge, dramatic helicopter shot that captures the Statue of Liberty in all her glory. Liberty’s face—solemn and serene as she looms above New York Harbor—gives way to the faces of two young women riding the Staten Island ferry to their Manhattan jobs. Cyn (Joan Cusack) and Tess (Melanie Griffith) sport Big Hair and Big Makeup. What we don’t see at first are the Big Dreams that will propel Tess, after some twists and turns, into the heady world of high finance.

The 1988 film Working Girl begins with a huge, dramatic helicopter shot that captures the Statue of Liberty in all her glory. Liberty’s face—solemn and serene as she looms above New York Harbor—gives way to the faces of two young women riding the Staten Island ferry to their Manhattan jobs. Cyn (Joan Cusack) and Tess (Melanie Griffith) sport Big Hair and Big Makeup. What we don’t see at first are the Big Dreams that will propel Tess, after some twists and turns, into the heady world of high finance.I re-watched Working Girl because, as the author of a new book on the implications of The Graduate, I’m fascinated by the cinema career of director Mike Nichols. Nichols, who has been accused of being cold and even bitter in his approach to art, has certainly made some dark films, with Carnal Knowledge perhaps at the head of the list. But Working Girl– something of a Cinderella romance -- taps into the sunnier side of Nichols. This film is optimistic in seeing that a smart and savvy young woman, one who keeps her wits about her and is not above a bit of strategic deceit, can make it past her working-class roots and the condescending title of “secretary” to succeed among big-business veterans.

Working Girl has always been a popular film. In its day it earned six Academy Award nominations (including Best Picture), and brought in an Oscar for Carly Simon’s powerful song, “Let the River Run.” And it was made with Mike Nichols’ usual careful attention to detail: locations, costumes, and casting are all impeccable. But in the wake of the #MeToo movement, it can be viewed in a slightly different light.

The film opens with a dirty trick. Tess, whose professional aspirations have led her to take night classes and read every bit of newsprint that comes her way, badly wants to advance beyond secretarial duties at the investment bank where she works. The guys in the nearby cubicles set her up for a meet-and-greet with Bob Speck, who supposedly has an opening for a bright young newcomer. Truth is—he’s a coke-snorting slimeball who only wants to get in her pants. (The fact that he’s played by the young Kevin Spacey, who recently has had his own #MeToo problems, makes the scene seem all the more current.)

But there’s more to come. Tess’s new boss, Katharine Parker (Sigourney Weaver) starts off sounding collegial and even sisterly. But she turns out to be even more of a snake than the egregious Bob. While she listens attentively to Tess’s bright business ideas, she’s secretly passing them off as her own. In the course of the film, canny businessmen ultimately prove themselves to be on Tess’s side, while the #1 bad apple is the one female we see in an executive position. So the feminism the film seems to espouse is two-pronged.

A further irony: handsome young Jack (Harrison Ford) comes to love Tess for her audacity and the sharpness of her mind. But he first flips over her at a social event when, clad in a fancy dress swiped from Katharine’s closet, she dazzles him with her looks. There’s a moment early on when she mildly gripes that a blue-collar Staten Island beau (Alec Baldwin!) insists on buying her Victoria’s Secret-style undies for all gift-giving occasions. But, as her hairstyle and clothing sense grow more sophisticated, she’s still got those sexy scanties on underneath, as the film makes amply clear. That’s Hollywood for you: however bright a woman may be, she’s still required to show sex appeal.

Published on May 08, 2018 09:42

May 4, 2018

May the Fourth Be With You (as you battle beyond the stars)

I didn’t realize until recently that May 4 is a new American holiday. Yes, it’s Star Wars Day (as in “May the fourth be with you” – it helps if you lisp). Hard to believe it’s been more than forty years since Luke Skywalker first picked up a lightsaber and Han Solo piloted the Millennium Falcon into our hearts. Since then, the Star War universe has become crowded with oddly-named characters, Disneyland has added some new attractions, and George Lucas has evolved into a very rich man.

I’ve never pretended that futuristic fantasy is my favorite genre. Still, the success of the original Star Wars (1977) inspired my former boss to shift gears in a big way. Since he launched his own production and distribution company, New World Pictures, in 1970, Roger Corman had always favored down-and-dirty genre films that could be shot quickly and cheaply, mostly on the streets of L.A. To a high degree, his movies depended on the energy that came from capturing life in the raw. But Star Wars changed all that. Suddenly Roger, always quick to capitalize on trends in the making, saw the advantage of owning a studio, the better to create special effects and launch a space opera of his own.

Roger’s minions spied out a promising piece of land, half of a city block, on Main Street in Venice, California. For years it had been the Hammond Lumber Yard. Because the site was only three blocks from the Pacific Ocean, it fell under the purview of the California Coastal Commission, then comprised of aging hippies who were deathly afraid of gentrification. After much wrangling, the group issued an ultimatum: that New World pledge not to modernize the buildings’ shabby exteriors, nor to improve their looks in any way. Almond, a savvy negotiator, looked grave, then promised to see what he could do, in exchange for major concessions on other points. Says he, “I went back to Roger and said, ‘I can close the deal but there’s one really onerous condition. We can’t modernize the outside of the buildings.’ Roger looked at me, I looked at him, and we just burst into laughter.” The joke, of course, is that Roger Corman is not a man to squander money on décor. For years the Hammond Lumber sign remained in place, and the occasional visitor would wander by in search of a two-by-four.

Roger’s attempt at Star Wars turned out to be a proving ground for several major talents. The script for Battle Beyond the Stars, a sort of outer-space variant on Akira Kurosawa’s timeless Seven Samurai, was crafted by a young writer named John Sayles, eager to move from writing magazine stories to making his way in the film industry. One day another newbie showed up, promoting a front-projection camera rig he’d designed to accommodate special-effects shots. Corman was unimpressed with his results, but James Cameron rebounded into the position of model maker, and then art director, devising sets out of little more than foamcore, hot glue, gaffer’s tape, and spraypaint. He had everyone collecting Styrofoam containers from McDonald’s hamburgers: when spraypainted silver, these looked impressive lining the walls of a spacecraft corridor. One Corman assistant describes how “if the actors should turn around quickly and slam into the wall, the whole thing would crumble.” That’s when Cormanites had to start eating more hamburgers.

Sayles and Cameron may have been bound for success, but not so the film’s director. An experienced production designer, he could not cope with actors and on-set complications. That’s when Roger himself quietly stepped in to direct the director.

Published on May 04, 2018 09:21

May 1, 2018

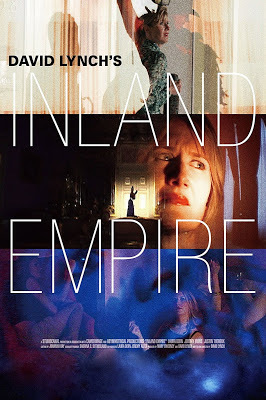

Inside the Inland Empire: “The Graduate” Rides Again

The Inland Empire is a picturesque term for a vaguely defined area of Southern California comprising parts of San Bernardino and Riverside counties, along with nearby communities. Some civic boosters include the Indio and Palm Springs areas, which means that the über-trendy Coachella Music and Arts Festival—where Beyoncé just made such a serious desert splash—is part of the Inland Empire too.

I was invited to speak on my new book, Seduced by Mrs. Robinson , for the Dome series at the San Bernardino County Museum. I’ve often seen this distinctive freeway-close complex (located in the city of Redlands) while driving to visit relatives at holiday time, but I had no idea what awaited me inside the museum’s geodesic dome. First of all, Inland Empire folks just seem to be a little nicer, a little friendlier, and much less harried than their L.A. counterparts. Before my talk, I also had time to check out the museum’s permanent displays. Most memorable was the so-called Remember Ramp, which contains useful items I remember all too well (a dial telephone, an adding machine, a manual typewriter) so that children can see—and fiddle with—the stuff that was a hit before their mothers were born. Yes, I once owned a turquoise Princess Phone just like the one in the acrylic display case. And Mrs. Robinson of The Graduate tried to summon the cops to scare Benjamin Braddock with just such a phone. (Hers was stark white; the lady didn’t go in for flashy pastels.)

After my talk, I treated myself to a night at the most celebrated hostelry of the region, Riverside’s venerable Mission Inn. This magnificent pile of vaguely Spanish arches, turrets, and balconies dates back to the early 20th century, in an era when the California citrus industry was golden. It’s known for playing host to presidents (Richard and Pat Nixon where married there, and a special chair was ordered for the comfort of our largest POTUS, William Howard Taft). But Hollywood celebrities in love with the area’s warm, dry climate also dropped in; there’s a charming tale about Cary Grant searching out the particularly comfy room in which he’d stayed on a previous visit.

Remarkably, the city of Riverside grew up around the hotel. Riverside’s civic buildings are located just up the street, and a more recent celebrity is now putting down roots nearby. Comic actor Cheech Marin, of Cheech and Chong fame, is establishing—a short walk from the Mission Inn—a museum to house his notable collection of Chicano art. It will be known as the Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art, Culture and Industry.

Coming home from the Inland Empire, I made a detour into the nearby Pomona Valley to see with my own eyes a famous location used in the filming of The Graduate. This is the United Methodist Church, the striking glass-and-stucco structure where Ben Braddock pounded on the glass of the upstairs balcony to alert his love, Elaine Robinson, that he had come to rescue her from a marriage to someone else. Back in the day, the presence of a film crew made the Methodist congregation uneasy. Today they’re proud to show off the premises to the film’s fans, will happily snap photos of visitors pounding in that famous balcony, and can spin yarns about other film shoots that came their way because of this one: Wayne’s World 2 and Bubble Boy, to name a few. Our guide remembered best of all the day a sexagenarian Dustin Hoffman showed up to rescue another young bride, all for the sake of an Audi commercial.

This one’s for Melissa Russo of the San Bernardino Museum, Cati Porter of Inlandia, and my delightful Riverside cousin, Rosalie Anderson.

Published on May 01, 2018 13:24

April 26, 2018

Notes from the Noir Fest: The World in Black and White

It’s always a kick to attend Hollywood’s Noir City festival, hosted by Eddie Muller and Alan Rode, honchos of the Film Noir Foundation. The venue is the historic Egyptian Theatre, which opened in 1922 with a lavish premiere of Michael Curtiz’s Robin Hood, starring Douglas Fairbanks. I’ve just learned that the theatre slightly pre-dates the mania for all things Egyptian that was sparked by the excavation of King Tut’s tomb later that same year. The Egyptian Theatre was exhibitor Sid Grauman’s primo showplace until the opening of the even kitschier Grauman’s Chinese, also on Hollywood Blvd., in 1927. Later the Egyptian sank into seediness, then was purchased from the city of Los Angeles by the American Cinematheque, with a mandate to restore it to its former glory.

When attending a screening at the Egyptian,. I always feel myself immersed in both Old Hollywood glamour and the slightly chaotic, slightly down-at-the-heels atmosphere that is Hollywood Blvd. today. There are fading mural of big-name celebs, and sidewalk stars dedicated to Tinseltown types I’ve never heard of. There are hustlers and gawkers and street people looking for a handout. There’s the venerable Larry Edmunds Bookshop, dedicated to all things movie-related, where I’m always sure of a warm welcome from Jeff, the long-time proprietor. And, of course, there’s Musso & Frank Grill, as old as the Egyptian, a watering hole where dry martinis and prime steaks have been served to everyone who was anyone in the Golden Age of Hollywood. The menu’s still classic, the booths are still full, and the food is great!

After being impeccably served at Musso’s (thanks for dinner, Alan!), I crossed the boulevard to the Chinese. The evening’s presentations included two Fifties noirs from Paramount Pictures, one of them rarely seen. I just read that Paramount, following some big flops of late, is feeling optimistic on the strength of its new low-budget thriller, A Quiet Place. The movies featured on this evening’s Noir City program are low-budget too, but very different from the rural environment captured by writer/director/star John Krasinski. Like most film noirs they are black-and-white evocations of an urban environment, one in which crime and chicanery abound. Part of the pleasure of a film noir is spotting L.A. landmarks (the Angel’s Flight funincular, Hollywood Forever cemetery, the Beverly Hills Hotel, a boxing match at the old Olympic Auditorium), even in films that theoretically take place somewhere in the mid-west.

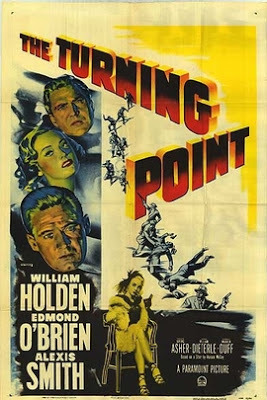

Paramount’s 1952 The Turning Point is not a ballet movie (that would have to wait until 1977), but rather a drama in which idealistic prosecutor Edmund O’Brien is not nearly so effective as hard-boiled journalist William Holden in ferreting out organized crime. Alexis Smith is the love interest , and the ending is appropriately downbeat. The twisty 1956 crime thriller Scarlet Street features several new Michael Curtiz discoveries who never made it big (seductress Carol Ohmart among them). There’s a jewel heist, lots of double-crossing, and a guest appearance by Nat “King” Cole singing “Never Let Me Go.”

But the biggest pleasure of old film noirs may be the wonderful mugs they assemble among the supporting cast. There’s craggy Ed Begley as a crime boss, Carolyn Jones in a teeny role as a floozy on the witness stand, E.G. Marshall as a stone-faced cop, and a whole assort of big lugs, skinny weasel-types (Danny Dayton!), and other nogoodniks. Maybe best of all, Broadway’s raucous Elaine Stritch shows up as the leading lady’s gal pal to provide comic relief.

Life in the noirs always seems so, well, black and white. I can’t wait until next year.

Noir City continues through Sunday, April 22.

Published on April 26, 2018 09:30

April 24, 2018

Not Staying Silent About “A Quiet Place”

Last year it was Jordan Peele’s Get Out. This year’s current box-office favorite is another modestly budgeted horror flick, John Krasinski’s A Quiet Place. Here’s another case of a well-liked performer (best known until now as the lovestruck Jim on TV’s The Office) branching out into writing and directing, with impressive results. True, A Quiet Place is not a cultural bombshell in the way that Get Out most certainly was. But what Krasinski has achieved is a well-paced little chiller that has audiences on the edge of their seats.

I came from the Roger Corman world, and so I certainly know my way around horror films and thrillers. (Many of the 170 films on which I worked fall into those categories.) We who know the ins and outs of low-budget filmmaking are well aware that horror is a great place for a novice filmmaker to start. The genre has many built-in fans who expect nothing more than a few good scares. You can shoot an effective horror film with a small cast and a limited number of locations. A Quiet Place enlists a total of 6 actors, It does require a large stretch of rural scenery, but most of the interiors take place in a simple house set. Of course, in a film about everyday people threatened by terrifying monsters, special effects are needed. But Krasinski follows the classic Corman dictum of barely showing the creatures at the beginning, so that we’re absorbed in the drama long before we acknowledge the scary adversary is just a guy in a rubber suit.

A Quiet Place never gets too intellectual about the nature of the threat the whole world is apparently facing. Mostly we’re caught up in the story of a family in crisis. Curiously, I was reminded more than once of Pa, Ma, and their daughters staving off locusts, blizzards, disease, and everything else in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie. The Ingalls family survived because they were accustomed to doing everything on their own, without help from the outside world. And the family in A Quiet Place, though they have access to electricity and modern electronics, are equally self-sufficient, terrific at improvising fixes when the chips are down. And from the time the movie begins, the chips are very much down: monsters are lurking and they seem unstoppable.

Horror films thrive on gimmicks, and A Quiet Place has a really good one: the monsters are blind, but their hyper-acute hearing makes it easy for them to track their prey. For the human family, the best defense is to tread as softly as possible. Parents and children walk barefoot indoors and out, and communicate mostly in sign language, They’re well versed in this because their teenaged daughter is deaf. In the manner of classic family dramas everywhere, she’s both the one who feels guiltiest about the dangers they all face andthe one who finally figures out the monsters’ fatal weakness. (Spoiler alert for Roger Corman fans: This weakness is not so far removed from the one on which we capitalized in our Concorde Pictures horror flick, The Terror Within.)

At a time when our daily lives seem ever noisier, it’s fascinating to be caught up in a film that’s so dependent on silence. Needless to say, the sound design for A Quiet Place is exemplary. It used to be, of course, that movies were entirely silent, but our imaginations filled them with chatter. How ironic that in a modern film with all manner of sound at its disposal, noise is something that we’re hoping not to hear.

Published on April 24, 2018 09:42

April 20, 2018

Kasell’s On The Air – What Radio Voices Mean to Us

The passing of former First Lady (and presidential mother) Barbara Bush has got me thinking. Mrs. Bush was not among my favorite First Ladies, but I still have a vivid picture of her: the “silver fox” hair, the sensible blue dresses, the three strands of faux pearls. For a politician (or perhaps especially a politician’s wife), a distinctive look is all-important. Just think of Mamie Eisenhower pink, Nancy Reagan red, Hillary Clinton’s pants suits, Michelle Obama’s toned arms, or – I suppose – Milania’s cheekbones and stilettos.

Another person we lost this week is unforgettable to me, but until now I hadn’t the slightest idea what he looked like. I’m talking about Carl Kasell, the public radio newscaster who just died at the age of 84. That’s the thing about radio personalities. It’s the voice, not the face, that makes all the difference. Which leads, of course, to the familiar adage that some talented performers have “a great face for radio.” Surely Garrison Keillor, who looks to me something like a bullfrog with a gland disorder, could have built his career in no other medium. Once we all grew accustomed to his sonorous voice and the whimsical way he delivered the news of Lake Woebegon, we were ready to accept his appearance and find it endearing. (At least, we did until the #MeToo movement gave us another picture to consider.)

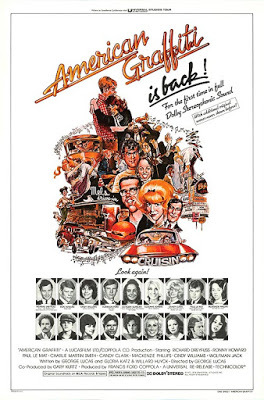

I guess in the old days of Top 40 radio, DJ’s made enough personal appearances that their faces became known. Some ended up on TV: Bob Crane (before his bizarre and tragic end) moved from a top-rated L.A. radio station to the starring role in a popular TV sitcom, Hogan’s Heroes. And one storyline in 1973’s American Graffiti involves a teenage boy barging in on his DJ hero, the real-life platter-spinner Wolfman Jack. Successful sports announcers like the great Vince Scully start out as friendly radio voices, but then segue into TV broadcasting. A few years back, I had to visit a dental specialist. When I emerged into the waiting room, I saw a seated man. He looked familiar, but it was not until he answered his ringing cell phone that I knew I was in Scully’s legendary presence. (He winked at me, obviously quite familiar with getting gasps of recognition as soon as he opened his mouth.)

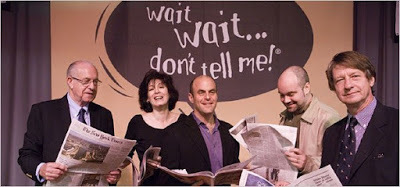

As a devoted NPR listener, I have my vocal favorites. Among them are Susan Stamberg and Terry Gross, but it was years before I knew what either of these ladies looked like. I also love to hear Sylvia Poggioli reporting from Rome. Is she a looker? I have absolutely no idea. Starting in 1977, Carl Kasell was the dignified disembodied baritone voice of authority that announced top news headlines on All Things Considered and Morning Edition. Then in 1998 he unleashed his inner comedian when he became the official announcer and scorekeeper for a brainy but goofy NPR quiz show, Wait Wait . . . Don’t Tell Me! On a broadcast whose centerpiece is the celebrity-centric “Not My Job,” it was Carl’s job to amuse listeners with outrageous impersonations of voices in the news. He also read limericks, smugly bantered with host Peter Sagal, and provided each segment with its top prize: “Carl’s voice on your home answering machine.” What I didn’t realize until now is that those answering-machine messages were impish comic gems. Here’s a quick sample: “Hello, I’m Carl Kasell from NPR. Jennifer and I have eloped. Please leave your message at the beep.”

Peter Sagal insists that “Carl has always been the heart of this show.” And, of course, its voice.

Here are some samples of Carl Kasell’s personalized voice-mail messages

Some "Wait Wait . . . Don't Tell Me!" cast members, with Carl on the left.

Some "Wait Wait . . . Don't Tell Me!" cast members, with Carl on the left.

Published on April 20, 2018 12:44

April 17, 2018

Othello: More Thoughts About the Moor

This past week, the Varsity Theater in the oh-so-arty town of Ashland, Oregon, played host to the Ashland Independent Film Festival. On Ashland’s main drag, intense-looking film lovers queued up for screenings, or gathered for pints and bites in local cafes. But Ashland is the rare American town where the focus is chiefly on live theatre, performed in repertory.

It all started back in 1935 when a local college professor of drama proposed staging two plays of Shakespeare as part of Ashland’s Independence Day festivities. The city fathers insisted that boxing matches be presented as well. As it turned out, the plays far out-earned the bouts, and the Oregon Shakespeare Festival was on its way to putting an old timber town on the cultural map. Soon Hollywood too was getting involved. Bing Crosby served as honorary festival director from 1949 to 1951, Charles Laughton volunteered to star in King Lear, and Stacy Keach made several appearances in the early 1960s.

By 1970, the festival had outgrown the outdoor Shakespearean stage that limited its performances to the summer months. A state-of-the-art indoor proscenium theatre was added in that year, followed by a flexible “black-box” for more experimental stagings. Today, OSF offers eleven plays in a season that stretches from February to November. There are always performances of plays by Shakespeare (including the most obscure of them), but new works are increasingly presented. On Saturday evening, I saw a world premiere of Manhatta, a striking new play that confronts the Native American experience both in the Manhatta of old and in today’s New York City.

But of course the heart of the OSF lies in its Shakespearean performances. In recent years some have been gimmicky, with more gender-bending than audience members are willing to tolerate. I was lucky to see an Othello that was effectively staged and beautifully played on the indoor Angus Bowmer stage. Yes, there was some toying with contemporary elements. Othello and his men wore modern naval uniforms, communicated at times via cell phone, and played out one long stretch while lifting weights at a health-club. But the play’s tragic jealousy was still front and center, even while our awareness of racism then and now gave this Othello a modern edge.

I’ve seen Othello on stage before, enacted by James Earl Jones, with Jill Clayburgh as his long-suffering Desdemona. But what really lingers in my mind is a filmed production that came out of England in 1965, starring (would you believe?) Laurence Olivier. In the early 20th century, it was not unusual for white actors to blacken their faces to play this fascinating role. Orson Welles had done it on screen back in 1951. But by the mid-Sixties, Americans were less comfortable with handing a black man’s role (and one of the best black roles ever written) over to a Caucasian. Olivier had played the part on stage, and the modestly-funded film (which also starred Maggie Smith as Othello’s beautiful young wife) was essentially a filmed play, attracting an audience of intellectual types. I remember the great Olivier as being even more astonishing than usual. He’d clearly put a lot of work into transforming himself, beyond the pigment of his skin. His Othello was barrel-chested, and he spoke in a resonant voice far deeper than Olivier’s usual timbre. Naturally, many took offense, with some critics likening his performance to an Al Jolson “Mammy” routine. I accept their point, but could never help cheering for the right of a great performer to try on a great role for size, even if it made him (understandably) uncomfortable in his skin.

Published on April 17, 2018 13:09

April 12, 2018

Laura Ingalls Wilder: How Green Was My Prairie

As a schoolgirl, of course I read Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House books from cover to cover. Years later I introduced them to my children. And they’re now being enjoyed by a third generation. It’s not just me and my family—Wilder’s books about growing up on America’s Great Plains are still savored by girls (and boys) the world over.

When you read Wilder’s books you feel that you, like she and her ma and pa, can do just about anything: grow corn, churn butter, trap a possum, make an acceptable doll out of odds and ends. Ma knew how to put hearty food on the table, no matter what. And when things got really tough, Pa’s fiddle knew how to soothe hurt feelings and make peace. Wilder’s books don’t skimp on the hard times: they talk about plagues of locusts, an illness that left an older sister blind, and a winter so long and brutal that the family feared starvation. But the books are a triumph of the can-do spirit, showing that with faith and a stoic acceptance of hardship it’s possible to surmount every challenge.

The Little House books, though, are hardly the whole story. They were written by a woman looking back on her pioneer upbringing with nostalgia for people and places that were now long gone. The books are a portrait of her own early years, but they should not be taken as fully accurate. Timelines are re-arranged, characters are combined, and some truly disturbing moments are wholly suppressed, so as not to dispel the books’ rosy glow. There’s also the fact that Laura and Almanzo’s daughter Rose, barely born in the last of the Little House books, served as her editor. The tension between an adoring mother and a headstrong, talented, but emotionally unstable daughter (one who spent money wildly and then turned to her frugal parents for loans) is something the Little House books don’t cover.

But that story comes out in Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder by Caroline Fraser, a scholar with her own pioneer roots. Her book, well researched and full of family photos, attempts to set the historic record straight. Late in Fraser’s book, there’s the matter of how the famous Little House on the Prairie television series came to be. At that point, Laura was dead and buried, as was daughter Rose. Throughout her life, Rose (a divorcee) had the habit of unofficially adopting various young men and supporting them in lavish style. One of these was a young attorney named Roger MacBride, an aspiring Libertarian politician. Upon Rose’s death, he managed to claim her mother’s copyrights, and made a deal with CBS. In the era following Vietnam and Watergate, audiences were eager for homespun, heartwarming tales. The Waltons appeared in 1972, and the Little House show followed in 1974.

Famously, episodes of the latter made Ronald Reagan weep. But Fraser is clearly dismayed by the liberties taken with Wilder’s work by Michael Landon and company. As director, head writer, and star, Landon imbued the role of Pa Ingalls with sexy glamour, favoring tight pants and unbearded cbin. He gave his prairie family a nice two-story mini-mansion instead of a sod dugout, and by the end of the series was borrowing old plot lines from Bonanza. “Walking to school,” says Fraser, “his Mary and Laura wore shoes rather than going barefoot, because Landon didn’t want his show children to be ‘the poorest kids in town.’” The producer who’d bought the series, Ed Friendly, liked to joke that it should be renamed “How Affluent is My Prairie?”

Published on April 12, 2018 09:43

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers