Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 86

August 15, 2017

“Here’s Looking at You, Casablanca”

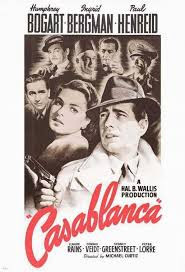

Casablanca lives on, at the intersection of Lincoln Blvd. and Rose Avenue, not far from me in Venice, California. It’s true there’s nothing even faintly Moroccan about this nearly forty-year-old restaurant: its menu features California-Mexican cuisine, complete with margaritas, guacamole, and flour tortillas made on the spot. But Casablanca Restaurant does boast Casbah-style décor, and houses a prime collection of memorabilia from the 1942 movie. The restaurant’s founders were so enamored of the denizens of Rick’s Café Américain that their parking lot has assigned parking spaces for Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, and the rest of the movie’s featured players, should they deign to show up.

Noah Isenberg, though SoCal born, doesn’t seem to know about Venice’s Casablanca Restaurant. But his new We’ll Always Have Casablanca is a paean to the many ways in which the seventy-five-year-old film – “Hollywood’s Most Beloved Movie” – is still with us today. This is the place to find comic allusions to Casablanca on The Simpsons and Saturday Night Life; he also tracks down various literary attempts, some of them bizarre, to update the love story of Rick Blaine and Ilsa Lund, chronicling what happens after he urges her to get on that plane with her husband because “the problems of three little people don't amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world.” Isenberg even introduces Rick’s Café Casablanca, a picturesque nightspot opened in 2004 by a former U.S. diplomat in Morocco to serve those who hanker for good seafood amid nostalgic reminders of a movie that was filmed in its entirety on the Warner Bros. backlot.

Though Casablanca is best remembered as a love story, it owes its impact partly to the fact that it was released just as Hitler and his Nazis were overrunning Europe. Isenberg is at his best in focusing on a cast filled with actual refugees, actors who’d fled to Hollywood from such places as Austria, Germany, and France to escape Nazi persecution. (Some of them ended up playing Nazi on screen to make ends meet.) The actors’ own personal sense of loss helps explain why the scene containing the singing of the Marseillaise in support of the Free French packs such a wallop. He also makes the excellent point that Humphrey Bogart’s Rick, the detached cynic who finally chooses political involvement, nicely represents the attitude of many Americans before (and even after) Pearl Harbor. The American public in the 1940s, notes Isenberg, tended to prefer isolationism, but films like Casablanca helped sell the appeal of a principled commitment to solving the world’s larger problems. Jack and Harry Warner, themselves from a Jewish immigrant background, boldly used their films in this period to address the specter of Nazism in Europe. One irony: though Casablanca highlights the desperation of the refugees, the specific threat to Jews in Nazi-controlled Europe is never mentioned.

Isenberg also traces the popularity of Casablanca into the Sixties, when scores of young campus activists identified with Humphrey Bogart’s iconic blend of idealism and cynical cool. That’s why Bogart-as-Rick posters were so visible in college dorm rooms in my day, and why theatres like the Brattle near Harvard University played Casablanca as part of an end-of-term ritual for many years. Now, as the Syrian refugee crisis makes headlines, the public’s appreciation for Casablanca seems to have waned not at all. It turns out that Senator Elizabeth Warren, of all people, watches the film each New Year’s Eve, seeing in it much relevance to our nation of immigrants. “Each time I watch it,” she writes, “Casablanca gives me hope.”

Published on August 15, 2017 13:20

August 11, 2017

Wild About Nature: Gary Ferguson’s "The Carry Home"

It’s a common Hollywood trope: people are transformed when they go back to nature. Think of the number of movies in which, while traipsing through the wilderness, protagonists discover their innermost selves, or confront their fundamental fears, or make peace with their haunted past. From the last decade alone, I can name several such films, all of them based on true stories of present-day Americans who—after a trip deep into nature—will never again be the same. There is, for instance, 127 Hours, in which James Franco, portraying the impetuous Aron Ralston, discovers the inner strength it will take to free himself after being pinned down by a boulder. In 2007’s Into the Wild, a young man played by Emile Hirsch journeys all the way to Alaska before realizing that his need for human contact is even greater than his obsession with the out-of-doors. And in 2014’s Wild, a recent divorcee named Cheryl Strayed (Reese Witherspoon) hits the road, hiking from the Mojave Desert to the border of Washington State, in search of self-redemption and relief from the memories of her mother’s fatal illness.

Strayed’s journey up the Pacific Crest Trail spotlights how ill-equipped she is at the start of her trek. Gary Ferguson’s wilderness journey is quite, quite different, but equally compelling. Though at its core is an intense grief, the story he tells in The Carry Home: Lessons from the American Wilderness builds to an unexpectedly upbeat ending. Ferguson, an award-winning essayist and science writer, was married for 25 years to a fellow Indianan named Jane. As Ferguson puts it in his beautifully lyrical prose, “We’d been restless children, destined to become restless adults. Proud members of the last generation to soothe the anger of youth not with Ritalin, but with road trips.”

The couple, bonding over a mutual love of nature, spent their lives both working and playing in the great outdoors. While Gary pursued his writing career from their Montana home base, Jane introduced young people to the beauties of Yellowstone National Park, and also served on search-and-rescue teams. For fun they hiked, skied, and canoed. It was a springtime canoe trip on Canada’s Kopka River, “when the leaves of the north country were washed in that impossible shade of lemonade green,” that the end came for Jane. After a tragic spill, Gary crawled away with a badly broken leg, but the waters claimed Jane’s life.

Gary explains what happened next, after Jane’s body was recovered and the local authorities dismissed their first assumption that the drowning involved foul play: “My redemption would come in the form of a last request Jane had made years before, asking me if she died, to scatter her ashes in her five favorite wilderness areas. And so I did. Five trips to five unshackled landscapes. At first, the journeys broke my heart. Later they helped me piece it together again.” His book cuts between a step-by-step accounting of that last fatal day on the river and a travelogue of the journeys he took, first alone and then with others, to return what was left of Jane to the wilderness that had claimed her life. We feel his emotions evolving, helped along by the passage of time and by some Native American wisdom that allowed him to slowly absorb the fact of her death into his own ongoing existence. Early in The Carry Home , Ferguson speaks of a “life lived as though nature were both wings and nest.” At the book’s end, having survived a tragic loss, he can again look to nature for inspiration and for solace.

Here’s a link to Thomas Curwen’s deeply-felt Los Angeles Times story about the end of Gary Ferguson’s grief journey. Curwen was a participant in that last hike.

Published on August 11, 2017 12:29

August 8, 2017

"The Graduate" and SoCal’s Endless Summer

If you’ve watched The Graduate over and over – as I have, preparing for the publication of my

Seduced by Mrs. Robinson

in November – you know that most of the film seems to take place during an endless summer. All of the movie’s daytime SoCal scenes are filled with such summer obligatories as backyard barbecues and dips in the pool. One of the film’s great touches is that when Anne Bancroft’s Mrs. Robinson shrugs off all her clothing to entice Benjamin, the tan lines of her bathing suit are clearly visible. (Director Mike Nichols, a pasty-faced New Yorker himself, issued sun lamps to his cast so that they’d all have the requisite bronzed glow.)

If you’ve watched The Graduate over and over – as I have, preparing for the publication of my

Seduced by Mrs. Robinson

in November – you know that most of the film seems to take place during an endless summer. All of the movie’s daytime SoCal scenes are filled with such summer obligatories as backyard barbecues and dips in the pool. One of the film’s great touches is that when Anne Bancroft’s Mrs. Robinson shrugs off all her clothing to entice Benjamin, the tan lines of her bathing suit are clearly visible. (Director Mike Nichols, a pasty-faced New Yorker himself, issued sun lamps to his cast so that they’d all have the requisite bronzed glow.)I bring this up now because I just heard an interview with writer D.J. Waldie, who recently published in the Los Angeles Times an op-ed titled “How Angelenos Invented the L.A. Summer—In the Beginning Was the Barbecue.” Waldie, an expert on Southern California history and culture, begins by explaining how the Mexican custom of cooking outdoors rather than inside stuffy adobe-walled kitchens was ultimately promoted by magazines like Sunset as a lifestyle choice well suited to L.A.’s warm, comfortable climate.

Then there’s the whole matter of tanning. Into the 1920s ocean bathers across the U.S. were fully covered up, with both men and women hiding their bare skin as much as possible. In SoCal, there were laws on the books to enforce public modesty. Says Waldie, “The Long Beach City Council determined the legal distance between swimsuit and knee in 1916. Santa Monica police still were arresting topless (male) sun bathers as late as 1929. Laguna Beach didn’t repeal its modesty law until 1940.” In the end, though, comfort won out over yards of soggy fabric. A new SoCal concept of beauty and propriety moved in; in typical SoCal fashion, exposure to the sun was promoted as benefitting one’s health.

Hollywood, of course, participated in this sell-job. In the 1930s and thereafter, pin-up photos of movie queens and their golden-brown male counterparts were everywhere. (Classic film buff Raquel Stecher of @QuelleLove has recently been celebrating summer by tweeting a whole raft of poolside shots of Hollywood lovelies, who make the outdoor life seem awfully enticing.) Then in 1959 Sandra Dee in Gidget transported teenagers across America to the beach for surfing and (mostly) innocent merriment. (I remember being startled by some then-surprising dialogue about the difference between a good girl – who goes home and goes to bed – and a nice girl, who does things in reverse order.)

By the early 1960s, summer SoCal style was a hit across the nation. American International Pictures reinforced the concept with its fun-in-the-sun teen movies, starting with Beach Party in 1963. Beach Party was quickly followed by such deathless classics as Muscle Beach Party, Beach Blanket Bingo, How to Stuff a Wild Bikini, and Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine. In these films, the bland young love of Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello was played off against surfside hijinks, as everyone baked in the sun.

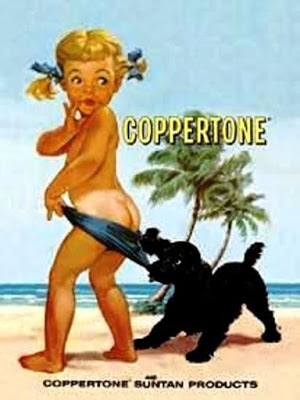

This was the era of surf music and Coppertone ads (dating from 1959) that exhorted the public, “Don’t be a paleface.” The rambunctious parodies of the little-girl-on-the beach ad campaign are still with us. But we’ve since learned about the dangers of skin cancer, and even Doonesbury’s Zonker Harris has given up on his career as a competitive tanner. Today UV protection is the watchword, and the sunbaked Benjamin Braddock is probably running to his dermatologist at this very moment, worried about a small patch of skin that may mean big trouble.

Published on August 08, 2017 10:32

August 4, 2017

David Letterman’s Biographer Uncovers a Sad Clown

Yes, I stay up late, but it rarely occurs to me to watch television. So I’m trusting in Jason Zinoman -- who covers comedy for the New York Times and has written the masterful Shock Value: How a Few Eccentric Outsiders Gave Us Nightmares, Conquered Hollywood, and Invented Modern Horror – to guide me through the intricacies of David Letterman’s unique career as a comic and talk show host. His new bestselling biography is called Letterman: The Last Giant of Late Night.

I discovered through Zinoman that one of Letterman’s original comic idols was mine was well: the late, great Steve Allen, who brought to his TV hosting duties (on the Tonight Show and elsewhere) an antic spirit and a willingness to do pretty much anything (wacky visits to the Hollywood Ranch Market! custard pie fights with the studio audience!) for a laugh. Letterman, of course, did much of the same, dropping watermelons from high places and donning a Velcro suit to hang from the walls of his studio. Zinoman notes the similarities of these pranks, but also zeroes in on one key difference: “Steve Allen played the role of a game, if occasionally reluctant, guinea pig delighted to be part of his experiments. He followed jokes with a big, booming cackle. By contrast, Letterman didn’t appear to be having a good time, like a man forced into this situation.” What he contributed to the insanity onstage was his own ironic detachment. What we saw on his face, says Zinoman, was perilously close to misery.

Zinoman’s point is that David Letterman, though highly ambitious and determined to make his way in the comedy world, seemed almost congenitally unable to enjoy the laughs he generated. Zinoman carefully delineates the various stages of Letterman’s career, as he moved from an NBC morning show to NBC’s Late Night with David Letterman to CBS’s Late Night, as well as the crushing moment when he was denied the chance to follow Johnny Carson as permanent host of the Tonight Show. Letterman’s style evolved over time, but the man himself seemed to become less and less comfortable in his skin, and far less willing to collaborate with those whose job was to make him look good.

The story of Merrill Markoe is a particularly vivid one. When Letterman was a nobody, she was his girlfriend, also an aspiring comic as well as someone with a special flair for writing. As Letterman rose through the TV ranks, she masterminded his comic persona, contributing to his shows such off-the-wall features as “Stupid Pet Tricks” and “Viewer Mail,” as well as the remote featurettes that sent him out into the community, honing his native sarcasm through chance encounters with everyday folk. But Markoe couldn’t count on Letterman’s affection and gratitude forever. Eventually she moved on, only to be summoned back when he needed a quick sequence that would feature him in conversation with an office intern named Stephanie Birkitt. Eventually Markoe figured out what was going on—Letterman was having an affair with Birkitt behind the back of his then-wife. On her blog Markoe made a heartbreaking joke: “This is a very emotional moment for me because Dave promised me many times that I was the only woman he would ever cheat on.”

But David Letterman is far from a total egotist. One of the most powerful moments of his career came in the wake of 9/11. Reeling from the disaster that had hit his beloved New York City, he spoke to his audience candidly and with great emotion. David Letterman moving beyond irony was truly something to see.

Published on August 04, 2017 10:05

August 1, 2017

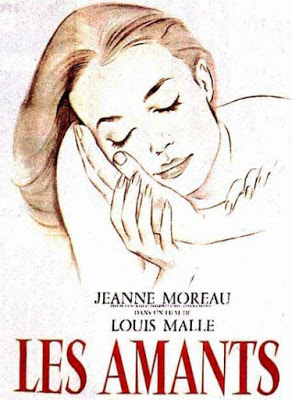

Memories of Jeanne Moreau (and Sam Shepard)

It’s not true, as some Hollywood onlookers claim, that Jeanne Moreau was once cast as Mrs. Robinson in The Graduate. Yes, her name came up as producer Larry Turman and director Mike Nichol contemplated having Benjamin Braddock lured into bed by a genuine Française. This would have been nicely in keeping with the French cinematic tradition of sophisticated older women initiating naïve young men into sexuality. But Turman and Nichols decided between themselves that the story of The Graduate needed to be an all-American one, and so Moreau was never offered the role.

It’s no surprise, though, that they considered Moreau for the role that eventually went to Anne Bancroft. Born in 1928, she would have been just the right age in 1967 to play a still-sexy woman with a daughter in college. And Turman and Nichols, both fans of the innovative new European cinematic movement known as the Nouvelle Vague(or New Wave), surely had seen Moreau in some of her most iconic roles. In 1958, she was directed by Louis Malle in Les Amants (The Lovers), playing a bored wife and mother who upends her comfortable marriage in the arms of a much younger archaeologist she’s just met. By the film’s end she has turned her back on her previous life, abandoning husband and daughter for an uncertain existence with her new flame.

In the U.S. The Lovers was particularly known for its role in a landmark obscenity case A screening of the film in Cleveland Heights, Ohio led to a criminal conviction of the theatre manager for public display of obscene material. He appealed to a deeply-split U.S. Supreme Court, where Justice Potter Stewart (not known as a flaming liberal) wrote a soon-to-be-famous commentary on Jacobellis v. Ohio. Stewart refused to label The Lovers pornographic, saying that, while he could not narrowly define pornography, “I know it when I see it.” (Happily, while few of the justices could agree on their own definition of what makes something obscene, Jacobellis won his case.)

The other film for which Moreau will never be forgotten is François Truffaut’s provocative Jules and Jim, which startled moviegoers in 1962 via its depiction of a lethal love triangle, with Moreau’s Catherine at its apex. (The two young men involved were Henri Serre and Austria’s Oskar Werner, who would later make a big impression in Stanley Kramer’s Ship of Fools.) The film’s inventive stylistics, coupled with its insights into the extremes of human behavior, assured it of serious attention from every film-lover out there.

As Moreau grew older, she won the respect and the friendship of such leading writers as Jean Cocteau, Jean Genet, Henry Miller, and Marguerite Duras. She acted for Orson Welles, once vocalized with Frank Sinatra at Carnegie Hall, and was briefly married to William Friedkin of The Exorcist fame. If Wikipedia is to be trusted, she had affairs with everyone from Pierre Cardin to Miles Davis. As recently as 2012 she was still making movies. When she died yesterday at the ripe old age of 89, no one could say that she hadn’t lived a full life.

Rest in peace, as well, to Sam Shepard, a talented actor (a Best Supporting Actor nominee for The Right Stuff) who was also one of our best contemporary playwrights. His tough, spare dramas of hard-scrabble family life were performed by major actors and won major awards (like the 1979 Pulitzer Prize for Buried Child). Shepard’s personal life included a two-decade relationship with Jessica Lange that produced two children. How sad that he succumbed to Lou Gehrig’s disease at the not-so-advanced age of 73.

Published on August 01, 2017 12:11

July 28, 2017

The Promise to Never Forget the Armenian Genocide

This year’s Toronto Film Festival will showcase the latest film by Angelina Jolie, First They Killed My Father. It’s based on the memoir of Loung Ung, who described in harrowing detail the decimation of her family by Cambodia’s murderous Khmer Rouge regime. Jolie’s strong personal connection with the birthplace of her son led her to use an all-Cambodian cast, and then to premiere the film in Cambodia’s Siem Reap.

Movies can be a powerful way of reminding viewers of injustices far beyond their shores. And it’s always invaluable when a filmmaker at the top of his (or her) game takes on the story of a genocide that the world would rather ignore. Think of the power of Holocaust movies, going all the way back to Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg (1961), the first Hollywood film to incorporate actual footage of emaciated Jews in Nazi concentration camps. Soon after came Sidney Lumet’s The Pawnbroker (1964) and other Holocaust-themed films, culminating in Steven Spielberg’s 1993 production, Schindler’s List. Sixteen years later, the persecution of Jewish civilians by Nazi Germany was still being explored, via Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds.

Which brings me to the plight of Turkey’s Armenians, whose years of suffering during World War I have still not been acknowledged as a genocide by the world’s political leaders. Armenians had lived in Turkey for centuries, but their Christian faith in a largely Muslim nation made them suspect, especially during the upheaval surrounding the Great War. Most Turks dispute what happened in 1915, but there’s plenty of evidence that under the Ottoman Turks, Armenians were rooted out of their ancestral homes and sent on a death march into the desert of neighboring Syria, where those who hadn’t fallen by the wayside were coldly massacred. It’s a terrible story, and one that the movie industry has barely acknowledged.

All that seemed about to change with the release of The Promise, a 2016 feature starring such major Hollywood names as Oscar Isaac and Christian Bale. This story of a tragic love triangle is set against the backdrop of the Armenian genocide, and several big-name celebrities of Armenian descent (Cher, for one) have given it their support. Mogul Kirk Kerkorian went so far, apparently, as to donate the entire production budget. Despite all this good will, The Promise was lambasted by many critics, and flopped at the box office, with some activists accusing Turkish genocide deniers of tipping the scales against it.

I didn’t see the film, but I’ve just finished reading the fascinating The Hundred-Year Walk by fellow journalist Dawn Anahid MacKeen. When Dawn discovered her grandfather’s meticulous journals of his fight for survival in the face of constant oppression, she knew she had to fly to Turkey and follow in his footsteps. She was well aware her journey was easy compared to his painful, stumbling path into the Syrian desert, where so many of his people were dying by the side of the road. But part of her goal was to search out, against all odds, the family of the Muslim tribal leader, Sheikh Hammud al-Aekleh, who’d given her grandfather safe harbor when he needed it most. Ultimately, this is a story of unexpected but well-earned salvation, but Dawn’s last chapter brings us into the precarious present, wherein Syria’s civil war now threatens a clan that were once remarkably kind to a young man in need.

Yet another message is Never Forget. In her opening, Dawn quotes Adolf Hitler, who told his followers in 1939, “Kill without pity or mercy. Who still talks nowadays of the extermination of the Armenians?”

Published on July 28, 2017 12:07

July 25, 2017

Driving Mr. Baby: The Paul Simon Connection

Midsummer seems the right time for a good old-fashioned car chase movie, and Edgar Wright’s gorgeously gas-guzzling Baby Driver more than fills the bill. With its driving scenes scored to the tunes throbbing out of the leading man’s iPod, Baby Driver can even be considered a musical, La La Land for the behind-the-wheel set. (It’s fascinating to contemplate what would happen if La La Land’s “Another Day of Sun” opening scene were transported to Baby Driver’s Atlanta. Ansel Elgort as Baby would never let a little thing like freeway gridlock stop him from getting--very quickly--where he needs to go.)

Baby is the getaway driver for an exceedingly rotten egg (Kevin Spacey), who rules with iron fist over a squad of ruthless criminals. Jamie Foxx and Jon Hamm (as a very different kind of Mad Man) play thugs with varying degrees of smarts but lots of anger issues in common. Needless to say, Baby has a backstory that explains what he’s doing in such loathsome company. Though he loves to drive, loves the thrill of being in motion, he’s by no means a hardened criminal type. He also loves his deaf foster father, and he’s starting to love the pretty little waitress (Lily James) who believes in him, and who wants nothing more than to drive into the sunset with her tunes blasting from the car stereo.

This is a movie that’s much dependent on its soundtrack. I didn’t recognize most of Baby’s music, though it’s fun to hear him crank up a golden oldie, “Tequila.” The use of familiar pop songs to score a film is not the newest of ideas. But it was very new in 1967 when director Mike Nichols decreed that The Graduate should be cut to such existing Simon and Garfunkel tunes as “The Sound of Silence” and “Parsley, Sage, Rosemary, and Thyme.” The original idea was for Paul Simon to devise some brand-new musical cuts for the film. Simon tried, but nothing seemed particularly promising, although Nichols thought there was something to be said for a scrap of a Simon ditty about Mrs. Roosevelt. (A simple shift to Mrs. Robinson, and music history was made.)

The financial backer of The Graduate, Joseph E. Levine, was irked in 1967 that Nichols wanted to score his film with songs written all the way back in 1964. Referring to the singing duo as “Simon and Schuster,” he bellowed at Nichols, “Every kid in America knows these old songs. You’ll be laughed off the screen.” Somehow that’s not what happened. The nostalgia built into “The Sound of Silence” and “Parsley, Sage” made them all the more poignant to the young audience. And this new approach to film scoring—using existing tunes to evoke the feeling of an era—would persist. Cut to 1973 when George Lucas chose classic fifties oldies like Fats Domino’s “Ain’t That a Shame,” Buddy Holly’s “That’ll Be the Day,” and the Clovers’ “Love Potion Number Nine” to establish the 1962 mood in American Graffiti.

Paul Simon also helped inspire Edgar Wright (a lover of genre films and the late George Romero) to write and direct Baby Driver. The film’s title is a steal from a bouncy Simon and Garfunkel track released back in 1970 on the duo’s Bridge Over Troubled Waters LP. Happily, it’s used over the movie’s end credits, certainly a jaunty way to wrap up the story. There was a time, following The Graduate, when Simon tried writing and starring in his own movie, One-Trick Pony. It didn’t work. Simon may be a musical genius, but a filmmaker he is not.

Published on July 25, 2017 11:46

July 21, 2017

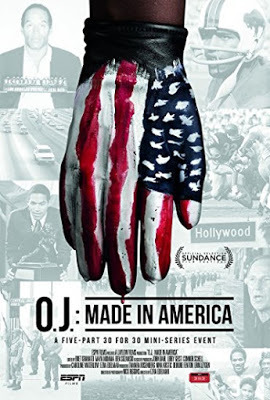

Paroling O.J. Simpson: The Juice is Again on the Loose

So O.J. Simpson is back in the news again. As viewers of a live coast-to-coast video stream of his parole hearing know full well, the Juice will soon walk free after almost nine years behind bars in Lovelock, Nevada. He was convicted in 2008 of participating in a bizarre caper that involved breaking into a Las Vegas hotel room to steal sports memorabilia. Before long he’ll be at liberty to resume searching for his wife’s killer on golf courses around the world.

I first heard the name O.J. Simpson at college football games, when his USC Trojans regularly trounced my alma mater, UCLA. As a running back, he was unstoppable—and charismatic. It wasn’t surprising that he went on to a record-setting pro career, first with the Buffalo Bills and then the San Francisco 49ers. It was while he was still playing football that he began to go Hollywood. He had featured roles in a number of thrillers, including The Klansman, The Towering Inferno, and The Cassandra Crossing. This was not surprising: there’s a long tradition of football greats appearing in action flicks, as Jim Brown did in 1967’s The Dirty Dozen. During my Roger Corman days, we cast the 49ers’ Roger Craig as a cop in something called Naked Obsession, because Corman was convinced that moviegoers would pay to see him chase down a bad guy.

O.J.’s star power helped him find roles in comedies too, like the spoofy Naked Gun series (1988, 1891, 1894). And such was his personal charm that many advertisers sought him to be their spokesperson. Most memorably, he did several commercials for Hertz Rental Car: he was always pictured sprinting through airports, leaping over any hurdles in his way, in order to claim his vehicle. (In that era, Hertz billed itself as the Superstar in Rent-a-Car.) Once when I was passing through LAX, I was tickled to see Simpson as a fellow passenger on the concourse. Like me he was walking, not running—which gave me a good giggle. I was delighted to catch a glimpse of him, because even those of us who didn’t follow pro football were not immune to his amiable persona.

That’s why it was so startling to find him connected with a murder case. It disturbed me to think of this iconic man as a criminal. And yet he had a talent for capturing the public imagination: even that infamous slow-motion white Bronco chase became riveting viewing. And the long years (1994-95) when he was on trial for murdering wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ron Goldman made for must-see TV.

Of course that was all two decades ago. We’ve had lots of other gruesome stories to entertain us since. But a duo of 2016 films returned us to the grim days of yesteryear. American Crime Story’s Inside Look: The People v. O.J. Simpson won a prestigious Emmy for Outstanding Short Form Non-Fiction or Reality Series. Though that show was a re-enactment of the Simpson story as a courtroom drama, the same year brought us a multipart (467 minute) documentary called O.J.: Made in America, which went on to win an Oscar for Best Documentary Feature. The documentary raised some Academy hackles because of its length and its TV connection, but it had the virtue of probing in some depth why O.J. Simpson’s story continues to fascinate. Why the “Made in America” subtitle? Because O.J.’s life somehow contains all the elements—not just money and murder but also race, class, gender, and celebrity culture—that make American life what it is today.

Published on July 21, 2017 10:05

July 18, 2017

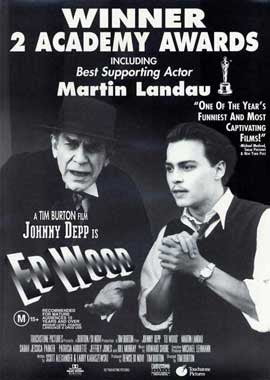

Martin Landau and George Romero: Two Movie Monuments We’ve Lost

In one fell swoop we’ve lost George Romero and Martin Landau. Romero, of course, was the filmmaker who gave us the original zombie apocalypse, starting with the essential 1968 cheapie, The Night of the Living Dead. That flick, in lurid black and white, came out in an era when our minds were on political assassinations (Kennedy, Kennedy, King), blood in the streets of our cities (Watts, Newark, Detroit), and an incomprehensible war overseas. Some of us were ready for nonstop horror on the screen, and The Night of the Living Dead delivered like gangbusters. The fact—coincidental though it might have been—that the film’s black hero is disastrously misunderstood by the forces of law and order was a powerful reminder of all that was (and still is) wrong with our nation.

Though Romero’s zombie films (like Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead) gradually became more expensive and elaborate, he never lost his taste for horror that slips covertly into social commentary. This set him apart from his many imitators, and from the current TV smash, The Walking Dead. As a former Roger Corman person, I salute him. On the IMDB I just located a memorable Romero quote: “I'm like my zombies. I won't stay dead!” As film fans, we can only hope.

George Romero won fame by filling the screen with movie antagonists who aren’t ill-intended; they’re just hungry. And Martin Landau’s unusual features always gave him what I considered a lean and hungry look. But no one would mistake him for a zombie: in both bad-guy and good-guy roles he was much too smart (and too ALIVE) to ever be mistaken for a member of Romero’s undead posse. Growing up, I loved watching him play a master of disguises on TV’s Mission: Impossible. But what has really stayed with me is his evil sidekick role in Hitchcock’s 1959 classic, North by Northwest. (He’s the one who stomps on Cary Grant’s fingers as our hero is dangling from Mt. Rushmore.) And, of course, there’s his Oscar-winning performance as screen legend Bela Lugosi in Ed Wood. Anyone who watches his acceptance speech on YouTube will come away with a sense of his passion for this role he so vividly brought to life.

Following Landau’s death, journalists have been coming forward with his words of wisdom about the craft of acting. Here’s what he told Rebecca Keegan in 2012: “No one shows their feelings except bad actors No one tries to cry. You try not to cry. No one tries to laugh. You try not to laugh. In a well-written script, dialogue is what a character is willing to say to another character. The 90 percent he isn’t [saying] is what I do for a living.”

I’m thinking of Romero and Landau as “monuments” because in the aftermath of my European travels I finally watched George Clooney’s 2014 film, The Monuments Men. It’s based on a true episode from the waning days of World War II, in which a gaggle of American and European art experts sneak behind enemy lines to rescue priceless masterpieces that the Nazis have looted from museums and churches, whether to keep or to destroy. Two of the greatest are from Belgium: Jan Van Eyck’s 15th century altarpiece, known as the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, and Michelangelo’s gorgeous 16thcentury Madonna and Child. A movie about saving great art is always going to grab me, but Clooney’s approach to the story seems uncomfortably close to The Dirty Dozen: unlikely military guys enjoy banter and hijinks, but finally get the job done.

The so-called Madonna of Bruges was the only Michelangelo work to leave Italy in the sculptor's lifetime. No zombies here!

The so-called Madonna of Bruges was the only Michelangelo work to leave Italy in the sculptor's lifetime. No zombies here!

Published on July 18, 2017 14:56

July 14, 2017

A Healthy Admiration for “The Big Sick”

The Big Sick is not the most inviting of movie titles. Too many other films of varying quality have started out with the same two words. The Big Chill, a poignant 1983 ensemble drama about the reunion of some Sixties activists, immediately springs to mind. But my much-battered Leonard Maltin guide lists pages of others: The Big Country (1958 Hollywood western extravaganza), The Big Doll House (sleazy 1971 women-in-prison exploitation flick from the Roger Corman film factory), The Big Easy (1987 crime yarn set in New Orleans), The Big Fisherman (1959 religious epic about the life of St. Peter), and so on. And let’s not forget classics like The Big Sleep and The Big Lebowski.

Whatever its title, though, The Big Sick is worth watching, both for its robust heart and for its keen eye for cultural differences. This film can be described as a romantic comedy in which an immigrant culture with strict matrimonial standards clashes against the far more casual American style of mating and marrying. This description, though, makes The Big Sick seem like a Pakistani version of the amiable but lightweight My Big Fat Greek Wedding. And Kumail Nanjiani and Emily V. Gordon’s script has far more on its mind than a meet-cute at the start and lots of wedding hoopla at the end.

Yes, Kumail (the film’s star as well as its screenwriter) does have some lively culture clashes with his old-school Pakistani parents, who foist on him a steady stream of Pakistani-American lovelies in full expectation that he’ll choose one and settle down to matrimonial bliss. This part of the film, though hilarious, is somewhat caricatured, especially his lovely mama reacting with feigned surprise to each young lady who just happens to be passing by as dinner is served. Even amid all the laughs, there’s some poignancy here: young women desperate to be brides; a young man who can’t bring himself to tell his parents that he’s already fallen for someone of a different ethnicity altogether.

The Big Sick is Kumail and Emily’s actual love story, and it’s a doozy. They meet at a Chicago comedy club when she reacts loudly to his stand-up routine. They mesh, despite their radically different backgrounds, because of a similarly warped sense of humor. After they’ve hopped into the sack together, she turns him away, quipping, “I’m not the kind of girl who has sex twice on the first date.” He, accused by a heckler of sympathizing with Islamic terrorists, admits that 9/11 was a tragic day: “We lost 19 of our best.” Things go well; then things go badly; then they break up . . . and that’s when she’s rushed to the emergency room, and enters a medically-induced coma.

The beating heart of the film is Kumail’s growing devotion to the comatose Emily, while he also forges a complex relationship with her worried parents. Holly Hunter and (of all people!) Ray Romano are full of surprises in these roles: she feisty and frantic with fear; he simultaneously hopeful, sad, and wracked with guilt. In short, they’re completely believable as human beings trying to cope with the possible loss of the person they love most. Like every parent who’s sat at a hospital bedside, I felt their pain. And also, thank goodness, their joy. Because this is a movie that earns its happy ending.

I shouldn’t overlook Zoe Kazan, who triumphs as the screen’s version of Emily. The daughter of two much-lauded Hollywood writers, she wrote and starred with real-life boyfriend Paul Dano in Ruby Sparks, another offbeat romance that brings a summer smile to my face.

Published on July 14, 2017 11:24

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers