Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 92

January 20, 2017

A Monster Calls: The Darkness Before the Dawn?

I tend to prefer movies made for grown-ups. And my friend Susan, a serious cineaste whose favorite films of 2016 include Neruda and Manchester by the Sea, can never be accused of opting for kiddie flicks. So when Susan suggested we check out A Monster Calls, I was surprised, to say the least. I’d seen the trailer, which looked visually intriguing. But the story (based on an acclaimed 2011 children’s novel) seemed all too familiar: a boy whose mother is dying of cancer finds solace through the sudden appearance of a fantasy figure. Somewhat like Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, young Colin O’Malley experiences three visitations. In his case, it’s not ghosts who come to visit, but rather a huge and mysterious tree-creature with three stories to tell.

For their work on this novel, author Patrick Ness and illustrator Jim Kay won two of Britain’s most esteemed literary prizes. Ness went on to write the screenplay, which is perhaps why the film’s characterizations ring so true. Colin (played by Lewis MacDougall) is not the adorable kid of so many poignant children’s films. His unhappiness constantly plays out on his face, whether he’s getting ready for his day without parental help, ducking the sympathies of his teachers, dealing with schoolyard bullies, or fending off the horrific nightmares that plague his sleep. Felicity Jones is his mum, an artist who’s still vibrant but fading fast; Toby Kebbell is the dad (now busy with his new family in California) who just can’t connect with the son he’s left behind. Only Sigourney Weaver, as the strait-laced grandmother with whom Colin must come to terms, seems questionable casting. But highest kudos for Liam Neeson, whose unearthly basso voice contributes so much to the presence of the tree-monster.

The monster’s stories are really what set this film apart from other variations on this same theme. Vividly told through the use of gorgeous animation, the stories are by no means obvious in their message. A prince commits murder, and gets away with it; little girls die when a parson turns to a healer for help that does not come. The stories make Colin angry, and prompt him to commit violent acts of his own. Ultimately, though, the presence of the monster leads him to an important acknowledgment of his feelings about his mother’s condition. At the end of the film, a fraught sort of peace descends.

A Monster Calls bears an unusual credit: “from an original idea by Siobhan Dowd.” Dowd was a celebrated author of young adult books. She had every intention of writing this story, but a terminal bout with breast cancer defeated her plans. As Patrick Ness has put it, “She had the characters, a premise, and a beginning. What she didn't have, unfortunately, was time.” She died in 2007, at the painfully early age of 47. A Monster Calls is a strong testament to her imagination and her spirit.

Perhaps it’s because mortality is a very real part of this film’s legacy that it hit me so hard. I don’t duck movies that focus on the darker side of life, but it’s not often that I see a film that genuinely moves me to tears. This one assuredly did. By the final fadeout there was a lot of sniffling going on in the screening room, as the all-adult audience confronted the fact that the pain of loss is a fundamental part of our human inheritance. Still, I think we all felt hopeful that life remains worth living, thanks to the power of love to transcend darkness. A lesson, perhaps, for our turbulent times.

Published on January 20, 2017 11:27

January 17, 2017

“Arrival”: How to Handle Illegal Aliens

This week, as the air waves were being dominated by politics and world issues, I went to see Arrival. This is hardly Hollywood’s first stab at the depiction of friendly (as opposed to scary) aliens. I think back to 1977’s Steven Spielberg hit, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, in which Richard Dreyfuss is welcomed aboard a craft piloted by extraterrestrials. Twenty years later, Robert Zemeckis shot Contact, in which Jodie Foster plays a SETI scientist chosen to interact with mysterious beings visiting from outer space. Two more decades have passed, and (in some political circles, at least) aliens are now interlopers of a different kind. But Arrival, directed by Denis Villeneuve, goes back to some classic assumptions: that the creatures making contact seek communication rather than warfare and that it’s a sensitive but brainy woman who’s best capable of knowing what to do and say. We’re now in, it should be noted, an era when women are being recognized for their STEM expertise, at least on the movie screen. We’ve had gutsy, heroic female astronauts in both Gravity and The Martian. The recent Hidden Figures is dedicated to three real-life African American women whose mathematical gifts made possible the U.S. manned space program. In Arrival, star Amy Adams is not exactly a scientist or engineer. Instead she’s a high-powered linguist who (in the word of her sidekick character, the physicist played by Jeremy Renner) thinks like a mathematician. And she’s the one American capable of deciphering the exotic written messages being sent her way by two unearthly beings code-named Abbott and Costello.

Arrival is based on an award-winning 1998 short science fiction tale by Ted Chiang, titled “Story of Your Life.”. I haven’t read Chiang’s work, but I’m told it’s a densely packed philosophical musing on the role of time and causality, because the extraterrestrial heptapod creatures studied by Amy Adams’ character, Dr. Louise Banks, have no sense of past, present, and future. Perhaps that’s why the throughline of the film version has me so confused. It’s clear enough from the film’s many memory flashes that Louise is suffering from the loss of her young daughter to a terrible illness..(Frankly, there’s something all too obligatory about the fact that all the STEM-superior young women in movies like Arrival and Gravity are compensating for the loss of a child.) But while watching Arrival I didn’t grasp what the movie was trying to say about basic chronology as a purely human construct. And I now suspect that the film critics I started reading after the lights came up understood better than I did because they had Chiang’s story to clue them in.

I needed no help, though, in understanding the film’s geopolitical messaging. It seems that alien visitations are simultaneously taking place in twelve locales spread throughout the world, including such unlikely outposts as Venezuela. At the U.S. site, located in rural Montana, scientists like Louise are closely monitored by Pentagon brass, but still manage to conduct their probes in a humanistic way. China and Russia, however, quickly move toward a militaristic posture, convinced as they are that the outer space invaders mean war. Louise becomes our only hope for convincing the nations of the world to work together peaceably for the sake of understanding and learning from the extraterrestrial visitors. It’s nice to see our heroine as a spokeswoman for peaceful coexistence. But this week some of us may be wondering – at a time when nationalism and xenophobia seem to be rapidly mounting around the globe – whether a worldwide push for peace can ever really be possible.

Published on January 17, 2017 14:53

January 13, 2017

20th Century Women: Struggling to Be All Right

Who can be said to be quintessential twentieth-century women? Adventurous sorts like Amelia Earhart? Political and social leaders like Golda Meir and Eleanor Roosevelt? Inspirations like Coretta Scott King? Style icons and glamour-girls like Jackie Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe? I’ve just seen the new film, 20th Century Women, so the question comes to me naturally. All the names I’ve mentioned above are worth considering. But I’ve just been lucky enough to see again (on an airplane!) Audrey Hepburn’s first big film,1953’s Roman Holiday. It’s a blithe little romance, though one with a bit of substance, broaching as it does the tension between personal freedom and the need to do one’s duty. And of course it’s proof that Audrey Hepburn was one of the most delicious actresses who ever lived.

Writers other than me have crowned Hepburn (Audrey, not Katharine) a major social influence. Sam Wasson’s 2010 bestseller, Fifth Avenue, 5 A.M., is subtitled Audrey Hepburn, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and the Dawn of the Modern Woman. Wasson’s argument is that Hepburn’s Holly Golightly character contains a very modern moral ambiguity that doesn’t distract from her charm. Though I loved Wasson’s book, I can’t say it convinced me on that point. My vision of Audrey Hepburn is still that of someone who’s pristine: girlish and adorable. And, as she is in Roman Holiday, a genuine princess.

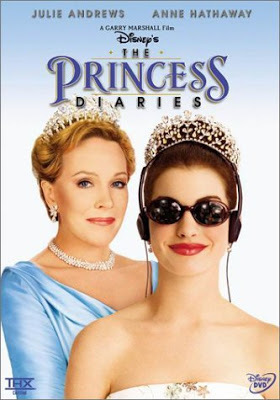

If you’ve been around little girls lately, you know that princesses are a very big deal. The Disney universe is full of them (see Frozen, Tangled, Brave, and now Moana). Why? Partly it’s because they wear great clothes. The modern Disney princess (unlike the very boring Sleeping Beauty) gets to go on adventures, and heroically save her people. At the same time, she’s always well-dressed, and when her adventures are over she gets to return to the castle and marry the prince (or at least an appealing stand-in). What more could a little girl want?

Which brings me to 20thCentury Women, the quirky semi-autobiographical film in which Mike Mills (who’d chronicled his father’s coming out in Beginners) reveals what it was like to be a young man coming of age in the late 1970s, surrounded by women working hard at the new concept of female empowerment. The #1 woman in young Jamie’s life is his mother, Dorothea, a smart, nervous chain-smoker who would like to have been a World War II pilot. As played by the always-gutsy Annette Bening, Dorothea is both lovable and exasperating; she’s capable of a joyous exuberance but remains at the same time fundamentally sad about the ways life has let her down. The film’s other two 20thcentury women are Abbie (Greta Gerwig), a punked-out artist with serious health issues, and Julie (Elle Fanning), a gorgeous high-schooler who sleeps around with unworthy men but demands of the sexually frustrated Jamie a purely platonic friendship. Quixotically, Dorothea turns to these two young women to help teach her son about life and love. Meanwhile he’s reading classic feminist tracts like Robin Morgan’s Sisterhood is Powerful to try to make sense of the world that his mother and her surrogates inhabit.

It’s been Annette Bening’s lot in recent years to play unusual “mom” roles. With spouse Warren Beatty she’s raised four children of her own, so she certainly knows the territory. In American Beauty she was an angry, hostile mother. In The Kids Are All Right, she played a devoted lesbian mother. .Dorothea is an equally worthy role for Bening: she captures both the love and the confusion of a mother trying desperately to make sure the kid is all right.

Published on January 13, 2017 11:11

January 10, 2017

Blah La Land?: A Dispatch from the City of Stars

This past Sunday evening, La La Land hosted the Golden Globes. And the Golden Globes ceremony, sponsored by the Hollywood Foreign Press corps, returned the favor by making a big winner out of Damien Chazelle’s Hollywood musical, La La Land. Well before the envelopes were opened, it was clear that La La Land was high on everyone’s list. Even the opening of the TV broadcast saluted Chazelle’s work by mimicking the film’s famous Hollywood traffic jam, with M.C. Jimmy Fallon among those caught up in the musical action.

Personally, I’d been waiting to see La La Land for a long time. As a native Angeleno (born in Hollywood, yet!) as well as a huge fan of movie musicals, I was eager to watch a paean to my birthplace, sung and danced by talented young performers. And Chazelle’s Whiplash was such a genuinely thrilling piece of work that I had the highest hopes. I’d heard Chazelle speak beautifully about the raison d’être for movie musicals: the way they capture emotion through fantasy; the way they sidestep conventional movie realism with a boldness that’s positively avant-garde. Chazelle’s favorites were my favorites too: Fred and Ginger, Singin’ in the Rain, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. So, yes, I was excited.

When I finally went to see La La Land, I was accompanied by two family members. One of them is (fingers crossed) starting to make a name for himself as a writer of stage musicals. We all expected to be bowled over. And there was a lot to like. F’rintance, that exuberant opening on an L.A. freeway when commuters give up on getting where they’re going, instead bounding out of their cars to sing and dance to “Another Day of Sun.” And the in-jokes that capture the spirit (if not exactly the reality) of my home town: everyone drives a Prius; despite the season the weather never quite changes. And the bold colors all the women are wearing. And the romantic use made of one of my favorite places, the Griffith Park Observatory. And an astonishing final “dream ballet” sequence à la An American in Paris. And my personal favorite little scene, when a star-crossed Ryan Gosling -- serenading sunset on the Hermosa Beach pier -- sweeps a very average middle-aged lady into a waltz as her spouse looks on, bemused.

So why the “yes, but”? I realized, while watching the film, that the central story line just wasn’t quite enough to hold me. The tale of Mia and Sebastian -- she a would-be actress, he a jazz pianist too pure to stray into other musical styles – left me a bit cold. I was less bothered that Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling don’t come off as trained singers and dancers. After all, both possess oodles of charm. But their on-again, off-again romance didn’t seem entirely worth rooting for. Not that all musicals are blessed with great screenplays. I know one of Chazelle’s big influences (and the source of that opening musical outburst) was Jacques Demy’s Les Demoiselles de Rochefort, a very charming, very French musical in which all the romantic comings and goings finally amount to very little. Still I, and my two moviegoing companions, felt just a bit cheated by La La Land’s script deficiencies.

And yet . . . as I hear snippets of those musical numbers, like the lovely “City of Stars,” I start remembering all the parts of La La Land that gave me pleasure. And made me – come to think of it – want to jump on top of my Lexus and start dancing. Who could ask for anything more?

Published on January 10, 2017 09:12

January 6, 2017

Letting Go of “Frozen”

I’m feeling a bit Frozentoday. And it has little to do with SoCal weather. As a kid, having zipped through loads of Greek mythology as well as Grimm’s fairy tales, I started in on Hans Christian Andersen. I’d known about the Danish author for years: the Frank Loesser musical version of Andersen’s life was the very first movie I ever remember seeing. In the role of Andersen, funnyman Danny Kaye performed spirited musical versions of “The Ugly Duckling,” “Thumbelina,” and (if memory serves) “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” But when I sat down with a fat volume of Andersen’s FairyTales, I was startled to discover at the heart of Andersen’s stories a darkness that Loesser and Kaye had managed to sidestep. For instance, consider Andersen’s original Little Mermaid. Hardly a pixieish Disney sprite, she was instead a mournful creature, one who gave up her voice and her seafaring identity for the sake of a mortal man who done her wrong. And then there was “The Snow Queen.” This tale, featuring a cold-blooded queen as well as shards of mirror that lodge in the heart, was so much grimmer than Grimm that I simply stopped reading.

I’m feeling a bit Frozentoday. And it has little to do with SoCal weather. As a kid, having zipped through loads of Greek mythology as well as Grimm’s fairy tales, I started in on Hans Christian Andersen. I’d known about the Danish author for years: the Frank Loesser musical version of Andersen’s life was the very first movie I ever remember seeing. In the role of Andersen, funnyman Danny Kaye performed spirited musical versions of “The Ugly Duckling,” “Thumbelina,” and (if memory serves) “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” But when I sat down with a fat volume of Andersen’s FairyTales, I was startled to discover at the heart of Andersen’s stories a darkness that Loesser and Kaye had managed to sidestep. For instance, consider Andersen’s original Little Mermaid. Hardly a pixieish Disney sprite, she was instead a mournful creature, one who gave up her voice and her seafaring identity for the sake of a mortal man who done her wrong. And then there was “The Snow Queen.” This tale, featuring a cold-blooded queen as well as shards of mirror that lodge in the heart, was so much grimmer than Grimm that I simply stopped reading. “The Snow Queen” has turned out to be the genesis of Disney’s Frozen. This 2013 release, now the top-grossing animated film of all time, contains plenty of Disney trademarks: charming leads, wacky sidekicks, affably anthropomorphized inanimate objects (here a snowman, Olaf, who romanticizes the joys of warm summer days). There’s also gorgeous scenery, lively musical interludes, and the joys of young love. Still, this is a darker story than the usual Disney fare. I was not surprised by the film’s female empowerment message: the idea that young women can be the controllers of their own destiny has been an article of faith in the Disney canon for quite a while. But when I finally caught up with Frozen, I was struck by the Nordic gloom that balances the film’s Anaheim affability.

I was late coming to Frozen. Instead of properly enjoying its scenic beauty on a wide screen in some stately movie palace (Hollywood’s El Capitan is the perfect place to see movies like this one), I checked out a copy from my local library. It was scratched and smudgy, surely the result of having been lovingly handled by a great many little girls. The result was that the DVD got stuck from time to time, leaving me with a picture that was – yes – frozen. As frustrating as this was, I persisted. After all, though I’d heard the hit song countless times, I still wasn’t sure exactly what Elsa was letting go of.

The answer surprised me. Since the film was intended to be family-friendly, I’d assumed that Queen Elsa, who is cursed with the ability to turn the world into ice with the wave of her hand, sings this song in the course of renouncing (letting go of) her magical powers. Not so. In fact, this is the moment when she (voiced by the full-throated Idina Menzel) essentially comes into her own, unleashing the full force of those powers even if this means cutting herself off forever from the rest of humankind. From this point onward, she’s downright scary, even toward her trusting younger sister, Anna.

For today’s little girls, even those too young to see the movie, Anna and Elsa are icons. What’s interesting is that the sisters do not represent good and bad in a conventional Disney way. Throughout all their frosty adventures, they care about one another. And at last, in Disney fashion, they don’t let go of family feelings.

Published on January 06, 2017 15:51

January 3, 2017

What “The Founder” Doesn’t Tell You About Ray Kroc and His Missus

For a few days in December, L.A. moviegoers could see The Founder, starring Michael Keaton as Ray Kroc, the honcho who spun the McDonald brothers’ small SoCal hamburger chain into solid gold. The brief local stay was intended to make the movie eligible for the 2017 Oscar and other awards, after which The Founder would be national released in late January. So far, however, the Weinstein brothers’ strategy doesn’t seem to be paying off. As of now, the only nominations the film and its star have garnered are for three AARP “Movies for Grownups” awards.

The focus in The Founder is on the misdeeds of Ray Kroc, who -- according to the filmmakers -- not only usurped the “founder” title from the McDonald brothers but also used nefarious means to cheat Mac and Dick out of money they were owed. This plot point is, it turns out, the end result of a typical Hollywood maneuver: making the film’s lead into an entirely despicable, though entertaining, con man. Not that Kroc was by any means a saint. He could be cold, greedy, and domineering, but in fact the McDonalds never accused him of breaking a promise about royalty payments. Here’s how journalist Lisa Napoli assesses the film’s claims of factuality: “The central premise, that Ray screwed the brothers out of a royalty, is patently false—and I am neither a Ray nor a McDonald’s apologist.”

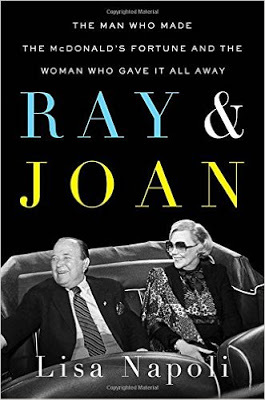

Lisa should know all about Ray Kroc’s business dealings, because Dutton has just published her well-researched Ray & Joan, a dual biography of Kroc and his adored third wife, Joan. The film version apparently pays much more attention to Kroc’s badly-treated first wife, who is played by the always effective Laura Linney. Joan is a character in the film too, but not an appealing one. It annoys Lisa that one of the film’s “facts”—that it is Joan who convinced Ray to save time and money at his fast-food outlets by substituting milkshake mix for real ice cream—is pure fiction. The Joan Kroc who emerges from Lisa’s pages is not simply a beautiful blonde who enjoys expensive clothing and jewelry. She is also a budding philanthropist whose warm-hearted response to those in need has truly altered the American landscape. Hence the full title of Lisa Napoli’s publication: Ray & Joan: The Man Who Made the McDonald’s Fortune and the Woman Who Gave It All Away.

Lisa contends that it is Joan Kroc, not Ray, who truly deserves the Hollywood treatment. Joan started out as a restaurant pianist in St. Paul, Minnesota, became the wife of a McDonald’s franchise owner in Rapid City, South Dakota, then left her spouse to marry the persistent Ray, 26 years her senior. But once they had set up luxurious housekeeping in Southern California, Joan was not content to remain a trophy wife. Rather, she set to work against some of her husband’s more contentious policies. After his death in 1984, she began quietly giving away multiple millions to charities she considered worthy. These included the Salvation Army, several centers for the treatment of addiction, North Dakota flood relief, and an Institute for International Peace Studies at Notre Dame University. Angelenos who have seen Paul Conrad’s chain-link nuclear cloud sculpture in front of the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium don’t usually realize it was secretly funded by Joan Kroc. And upon her death in 2003 it was announced she was leaving a bequest of $225 million to National Public Radio.

No wonder that by the end of her life she was often called St. Joan of the Arches.

Published on January 03, 2017 21:39

December 30, 2016

Debbie Reynolds: Star Mother

What a terrible irony—in death, Golden Age star Debbie Reynolds is mostly being referred to as Carrie Fisher’s mother. Over the course of her forty-year career, Fisher never achieved the level of moviestardom that her mother enjoyed. On the other hand, Reynolds’ fatal stroke (at 84) just one day after Fisher succumbed to heart failure (at 60) is so very startling that I suspect the two will always find themselves linked in the public mind.

It was not always so. Back in 1952 the barely 20-year-old Reynolds was the toast of the town after nabbing the ingénue role in Singin’ in the Rain. The part of Kathy Selden, a pert chorus girl in the early days of talkies, required her to sing (something she was good at) and dance (something she was not). To keep up with expert hoofers Donald O’Connor and Gene Kelly, she was coached by Kelly, a stern taskmaster. So grueling were their practice sessions that it’s remarkable she looks so carefree in numbers like “Good Morning.” (One charming bit of trivia: as part of the story, Reynolds’ low, sweet speaking voice replaces the shrill and nasal on-camera enunciations of Lina Lamont, the screen diva played by Jean Hagen. The problem was that Reynolds’ slight Texas twang lacked the elegant sound the script required. So Hagen herself was called upon to dub in the lines, using her own natural register rather than Lina Lamont’s unforgettable squawk. Got that?)

Early on, Reynolds consistently played women who are spunky, but still subscribe to conventional values. In The Tender Trap (1955), 23-year-old Reynolds lands 40-year-old Frank Sinatra. He plays a ladies’ man with no use for domesticity, until the adorable Debbie convinces him he’d be happier with a home and babies. Similar roles marked other films, including Tammy and the Bachelor. In the next decade, she stretched, but just a bit, playing a spunky frontier woman in How the West Was Won (1962), and then the really spunky lead in the screen version of a Broadway musical hit, The Unsinkable Molly Brown. Her theme song in that film, “I Ain’t Down Yet,” served to sum up the rest of her career, as well as her turbulent personal life.

In 1955 she had married nice-boy crooner Eddie Fisher. The two of them starred in a 1956 comedy, Bundle of Joy, that was meant to reflect their status as the perfect Hollywood young-marrieds. That same year, Debbie gave birth to Carrie; son Todd followed in 1958. But a year later the perfect marriage was on the rocks, thanks to Eddie Fisher’s dalliance with the newly-widowed Elizabeth Taylor. The scandal enveloped everyone: I remember reading at the time that Debbie’s publicist made sure she had diaper pins affixed to her blouse to help ratchet up sympathy when the press came to visit. (A second marriage, to millionaire businessman Harry Karl, was also a disaster – his gambling habit sapped her fortune as well as his own.)

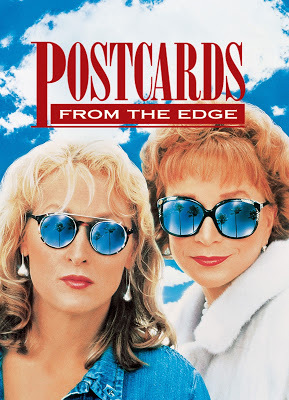

Throughout it all, Reynolds remained active, in both business matters and humanitarian endeavors. She also kept performing, most notably playing an addled mom in Albert Brooks’ Mother (1996)/ In 1990 the rumor was that her daughter’s deeply satiric Postcards from the Edge reflected her own imperious style of mothering. No question that there was strain, at times, between Carrie Fisher and her mom. But in early 2017, HBO will air Bright Lights, an acclaimed documentary chronicling the connection between Debbie and Carrie, with a focus on the unshakable bond between them. No one who worked on it could have guessed that it would be their valedictory.

Published on December 30, 2016 14:52

December 27, 2016

Carrie Fisher and Zsa Zsa: Chutzpah a la Carte

It’s not a good time for pop music. The sudden death of singer George Michael adds his name to a list of musical superstars who will not make it to 2017: David Bowie, Prince, Leonard Cohen.

And this morning brought the news of the passing of Carrie Fisher. She had seemed to be stable after suffering a heart stoppage on December 23 while flying from London to L.A. But her death was a final twist in a life that had already had many. Fisher, of course, was best known for playing Princess Leia in the original Star Wars films. I admit I’m not a huge fan of what George Lucas wrought, beginning in 1977. And Fisher’s bagel-haired character never held much charm for me. I was, however, taken with her presence in 2015’s Star Wars: The Force Awakens, where she appeared as a strong, mature, and knowing woman. Her interaction in that film with a greying Harrison Ford was particularly striking because (as all of us learned from her 2016 memoir) she had plunged into a three-month affair with the very married Ford on the set of the original Star Wars film.

The title of Fisher’s new memoir, The Princess Diarist, reveals the wit she always had in spades. In fact, I’m far more interested in Fisher the writer than in Fisher the actress. She always seemed supremely honest about her eventful time on earth: she wrote about her bipolar diagnosis and about her abuse of drugs and alcohol in a 2008 memoir, Wishful Drinking. She was also one of Hollywood’s most go-to script doctors, having polished and sharpened such hit screenplays as Sister Act and The Wedding Singer. She adapted her first novel, Postcards from the Edge, into a successful Hollywood film, starring Meryl Streep and Shirley MacLaine. This story of a young actress trying to recover from drug addiction while living with her ageing screen-star mother was by all accounts a reflection of Fisher’s own tense relationship with her mother, Debbie Reynolds. Reynolds, of course, was once known as a winsome ingénue who lost husband Eddie Fisher to homewrecker Elizabeth Taylor. The public knew her as sweet and vulnerable, but Fisher put forth the Tiger Mom aspects of Reynolds’ personality for all the world to see.

That took chutzpah. And of course chutzpah was one of the defining characteristics of the late Zsa Zsa Gabor. The Hungarian beauty, who parlayed her looks and charm into a Hollywood career that had little to do with acting chops, was a master at playing herself. Her husbands (nine of them) far outnumbered her major dramatic roles, but television hosts loved her ability to poke fun at her own image. Sample: “I am a marvelous housekeeper: Every time I leave a man I keep his house.” And then there were the headlines she made in 1989 when she slapped a Beverly Hills traffic cop.

Back when I was a Brownie Scout, I appeared in a playlet with other troop members. Afterwards, to celebrate, our parents took us to a fancy Beverly Hills ice cream parlor, Blum’s. There in the nearly empty restaurant sat a glamorous lady holding a Pekingese pooch while spooning a sundae into her pretty mouth. We young girls, fascinated by the dog, crept over to chat, while our parents nudged each other. Yes, it was Zsa Zsa, though her name meant nothing to us youngsters. We never stopped to wonder (as our parents must have) how she dared take her dog into a restaurant. Chutzpah, Beverly Hills style! Too bad the end of her life was much less carefree.

Published on December 27, 2016 17:41

December 23, 2016

John Glenn: That Magnificent Man in His Flying Machine

When I scheduled a December trip to snowy Ohio, I had no idea I’d end up at a public funeral for one of America’s most famous astronauts. The life of John Glenn (July 18, 1921 to December 8, 2016) was celebrated last Saturday in a large auditorium on the campus of Ohio State University. And I was there, along with Ethel Kennedy, Vice-President Joe Biden, the top man at NASA, and a Marine honor guard in full regalia. Glenn himself was present too, lying in state in a flag-draped casket.

We onlookers learned -- through musical selections, well-crafted speeches, and video clips -- of Glenn’s life of public service and private rectitude. Though his origins were modest, he early on seemed destined to do great things. As a much-decorated fighter pilot in the U.S. Marine Corps, he served in World War II and in Korea. In 1959, he was one of seven military test pilots selected to become the U.S.’s first men in space. On February 7, 1962, Glenn was the first American to orbit the earth. Later, having resigned from NASA, he entered politics, winning a U.S. Senate seat in 1974 and holding it until 1999. A lifelong Democrat, he became close friends with members of the Kennedy family. I was surprised to learn it was he, following the assassination of Robert Kennedy in Los Angeles, who had the painful task of breaking the news to the Kennedy children back home.

Though many of the speeches concerned his public accomplishments, I was most taken with those that revealed the private man. Glenn’s son and daughter spoke intimately about their dad’s enthusiasms: old westerns, chipmunks, hummingbirds, round tables, barbecued steak served medium rare. He taught his kids to build a perfect bonfire, and moved them with his tuneful tenor rendition of “The September Song.” They recalled him greeting a good report card with a question: “What have you done for our country today?” And they haven’t forgotten him turning down a $1 million offer to be featured on a Wheaties box. Above all, every speaker agreed on his steadfast love for his Annie, to whom he was married for 73 years. Said Vice-President Biden, “You taught us all how to love.”

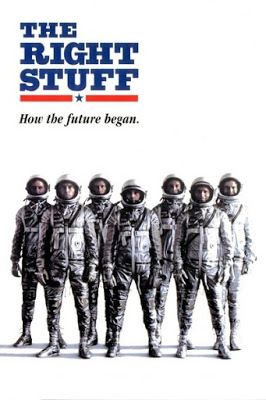

It’s no surprise to learn that John Glenn has been featured in a number of films. Several were documentaries, like 1998’s John Glenn: American Hero, a TV movie that was timed to commemorate his return to space, at the age of 77, aboard the space shuttle Discovery. But Glenn was also a major character (played by Ed Harris) in Philip Kaufman’s 1983 screen adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s The Right Stuff. This story of the original Mercury astronauts does not in any way idealize these so-called heroes. In fact, they’re depicted as cranky, often raunchy guys all too ready to check out the space groupies flocking to Cape Canaveral. Glenn, though, is the big exception. No question he’s cocky and ambitious, but he’s also the astronaut most aware of the power of public opinion. That’s why he can be found lecturing the others on the necessity of good behavior.

This week’s new release, Hidden Figures, also features Glenn. This is the true story of an unsung group of African-American female mathematicians whose work helped validate the science behind the Mercury launches. The movie shows Glenn refusing to fly his mission unless its computer-generated calculations are verified by math whiz Katherine Johnson (Taraji P. Henson). This sounds like a Hollywood touch, but I’m happy to say that Glenn’s faith in a smart black woman is truly a part of history.

Published on December 23, 2016 10:53

December 20, 2016

To Sir, With Movies

We’ve lost some major figures lately. Though they made their mark in a variety of fields, their public personas were large enough to ensure that they’d show up in popular movies. Fidel Castro of course appeared in Cuban films, usually as himself. I was also nonplussed to learn, via the invaluable Internet Movie Database, that in 1946 he performed as an extra in a 1946 MGM musical called Holiday in Mexico, in which the U.S. Ambassador's daughter (Jane Powell) falls for a Mexican pianist (Jose Iturbi) old enough to be her grandfather. Who knew? (Castro does not appear in Joe Dante’s 1993 Cuban Missile Crisis comedy, Matinee, but his aura hangs over the film like an invisible apparition.)

Then there’s John Glenn, by far the most telegenic of all the American astronauts. Glenn, as astronaut and as public servant, was no stranger to the movie screen. I can think, right off the bat, of three movies in which he was featured. But Glenn, who was memorialized in Columbus, Ohio on Saturday, deserves a post of his own. Which is why I’ll move on to the death of someone quite a bit more obscure: Ever hear of E.R. Braithwaite?

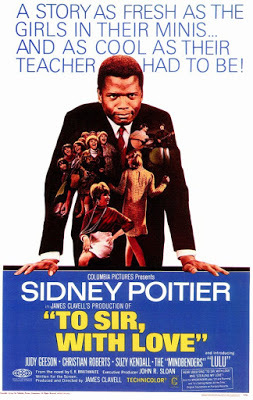

Braithwaite, who just passed away at the ripe old age of 104, had a busy life, serving as an educator, an author, and a diplomat. Born in what was then British Guinea in 1912, he was a pilot in the Royal Air Force during World War II, and graduated from posh Cambridge University with a degree in physics. It was while job-hunting that he – a black man -- first became aware of institutionalized racism in Britain. Struggling to find a job and a place to live, he ended up accepting a teaching post in a decrepit secondary school in the East End of London. His students, though mostly white, were a down-at-the-heels bunch, many of them hostile to blacks, but over the nine years of his teaching career he gradually earned their respect. Out of that experience came a memoir, 1959’s To Sir, With Love.

Naturally, there was a Hollywood ending. In the Sixties, audiences were hungry for films in which a noble black man (usually Sidney Poitier) finds love and respect. To Sir, With Love became one of three hit films that made Poitier the hottest box office attraction of the year 1967. In Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, he found love with a beautiful young white woman, and earned her father’s blessing for the interracial union. In the Heat of the Night (1967’s Best Picture winner) showed him, as a Philly police detective, solving a murder case in a backwards Southern town, and then winning the respect of the good-ol’-boy local sheriff. To Sir, With Love, by far the sappiest of the three, gave him the opportunity to tame a roomful of young British hooligans by teaching fair play, manners, and how to make a salad. (The film also spawned a pop hit, sung by the then-popular Lulu, who played one of the students.) Author Braithwaite was by no means enamored of the film version of his story. According to his obituary, he was annoyed that the film played down his interracial romance with a fellow teacher. And he understandably found Poitier’s approach to his students in the film overly simplistic. Though the film character based on his life wins over students by such stunts as taking them on an impromptu museum trip, Braithwaite was quoted as griping that “the movie made it look like fun and games." But that’s what Hollywood is about: fun and games, right?

Published on December 20, 2016 09:00

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers