Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 105

October 30, 2015

Halloween Horror Story

It’s that time of year again, when the mildest of people are wearing their Nightmare Before Christmas T-shirts in banks and doctors’ offices. In my weekly Zumba class, a soft-spoken man who always stands near the back of the room had covered his head with a blood-splattered pillow case. Everyone, it seems, loves the chills and thrills of Halloween. Latin Americans have the right idea in their celebration of Dia de Los Muertos, a day in which to conquer one’s fear of death by mocking its excesses and remembering its victims. In L.A. it’s easy to find grinning calaveras (skeletons) and sugar skulls, along with candles and eccentric altars dedicated to loved ones who are no more.

My former boss, B-movie maven Roger Corman, made much of his reputation on classy (though low-budget) horror films like House of Usher and The Tomb of Ligeia, based on the scary stories of Edgar Allan Poe. He also detoured into horror comedies like Little Shop of Horrors and Bucket of Blood. Some of his modern-dress horror films, like 1959’s The Wasp Woman and 1963’s X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes addressed one of the period’s genuine fears by focusing on the dangers of science run amok.

In fact, as horror-movie scholars (yes, they exist!) have pointed out, horror films succeed best when they capture the dread lurking within the public mind. Just as each era has its own bugaboos, it has its own preferred approach to horror. Just after World War II, which had ended with the unleashing of atomic power, horror movies naturally reflected a general fear of the A-Bomb. Such films as Godzilla(1954) explicitly tied their unstoppable monsters to fallout from the Atomic Age. The Fifties were also a time when the need for social conformity seemed to be spreading its own kind of poison. That’s why Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) resonated with the public at large.

By the 1960s, with social unrest on the rise, it’s no wonder that Night of the Living Dead (1968) struck a chord. Filmmaker George Romero has always said that the casting of a black actor in the chief good-guy role was not intended to send a social message. (On Romeo’s ultra-low-budget production, Duane Jones was simply the best man for the job.) But the fact that Jones’ character, mistaken for a zombie, is shot dead by cops trying to re-establish law and order spoke loudly to audiences in an era marked by interracial stand-offs.

In 1978, horror found a new home. The horror film had long been associated with creepy castles, or else with gritty urban environments. But in John Carpenter’s Halloween, horror invaded white-picket-fence suburbia. The message (as reiterated in later films like A Nightmare on Elm Street) was that no one is safe anywhere.

When I was Roger’s story editor at Concorde-New Horizons in the early 1990s, vampire stories had come into fashion. (See Coppola’s 1992 Dracula and our own To Sleep with a Vampire, among others.) And why not? AIDS was raging, and the vampire’s bite suggested symbolically a disease transmitted through blood. Now, at least on television, we seem to be back to zombies. I’m not quite sure why they’re the horror story of the moment. But (without casting any aspersions), I suspect that those poor bedraggled souls flooding into Europe from the Middle East must appear -- to those who don’t know their story and don’t speak their language -- as a mindless invading horde. For refugees like these, I guess, Halloween is a daily occurrence. Without, of course, all the candy.

And boo to you, too!

Published on October 30, 2015 11:21

October 27, 2015

Maureen O’Hara: When Irish Eyes Were Flashing

I admit I thought Maureen O’Hara had died long ago, until I learned she’d be receiving the 2014 Governors Award given by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for her stellar contributions to Hollywood. She was then 94, but her hair was still a flaming red (with, doubtless, a little help from her friends) and her fiery spirit was still intact. Word is that toward the end of her speech, as her words became garbled and disjointed, her microphone was quickly unclipped—and she made her displeasure abundantly clear. Good for her! Old age demands its privileges, and being long-winded should be one of them. In any case, she’s beyond all that now. Maureen O’Hara, pride of the Emerald Isle, died in her sleep on October 24, 2015, in (of all places) Boise, Idaho.

My late parents, who had little use for war movies or westerns, were hardly big John Wayne fans. Nor did they idolize Golden Age director John Ford. But they made a big exception for The Quiet Man, the 1952 romantic comedy—filmed in County Mayo in glorious Technicolor—that won Ford his fourth Oscar and filled the screen with his love for the Auld Sod. It’s a wild and wooly romp about an Irish-born American boxer who (having accidently killed a man in the ring) has hung up his gloves for good. Which sparks great outrage when he refuses to go to battle for his new wife in order to secure from her cantankerous brother (Victor McLaglen) the dowry to which she’s entitled. O’Hara, of course, was cast as the wife, a tempestuous free spirit who prizes her independence and her heritage above all. Others in the cast include such Irish treasures as Barry Fitzgerald and Jack MacGowran. And the film, of course, ends in a knockdown dragout brawl to end all comic brawls. It’s an ending that even a confirmed pacifist can enjoy.

In all, O’Hara played opposite John Wayne in five movies. It’s been widely quoted that he paid her the ultimate John Wayne compliment: “I’ve had many friends, and I prefer the company of men, except for Maureen O’Hara,” he said. “She is a great guy.” Most moviegoers, though, would hardly think of her as a “guy.” Her green eyes, red hair, and creamy complexion gave her the Hollywood nickname The Queen of Technicolor. Ironically, though, some of her best-known roles were in black-and-white films. Like the poignant How Green Was My Valley (1941), another John Ford production, this one set in a Welsh coal-mining village but filmed in the decidedly un-Welsh Santa Monica Mountains. (I’ve been lucky enough to visit the old Los Angeles Welsh church, once a synagogue, that contributed its choir to the soundtrack of this film.) In 1947, O’Hara starred in another memorable black-and-white movie, playing little Natalie Wood’s unhappy mother in the original Miracle on 34th Street. Fourteen years later, this time in living color, she was mom to one incarnation of Hayley Mills in the first go-round of The Parent Trap.

I encourage Maureen O’Hara fans to check out a wonderful Huffington Post reminiscence by Mike Kaplan, a former Hollywood jack-of-all trades whom I was lucky to meet at a Santa Monica coffeehouse when his legendary poster collection was being displayed at the Academy. He’s worked as a producer, director, and publicist, and has been closely linked to the works of Stanley Kubrick and Robert Altman. Kaplan met O’Hara, his boyhood crush, in Boise, and it sounds as if he had a lot to do with making her honorary Oscar a reality. Thanks, Mike!

Published on October 27, 2015 12:51

October 23, 2015

USC’s Steve Sarkisian: How Not to Go Hollywood

Fans of the University of Southern California Trojans are still reeling from the sudden dismissal of head football coach Steve Sarkisian. Sarkisian, a former member of the USC coaching staff, had moved on to head the football program at the University of Washington, where his team scored some dramatic wins over longtime rivals. He was lured back to USC in 2014, and had hopes of another stellar season this year. Then it became all too clear that the coach was fighting a drinking problem. A divorce that was announced in April probably contributed, but there were rumblings about alcoholic lapses back in his Seattle days. At USC this fall, Sarkisian missed practices and behaved bizarrely at a major booster event; several players admitted to smelling liquor on his breath. A brief leave of absence hardly solved matters, and his USC contract was terminated on October 12, 2015, with the football season barely underway.

This is not the way things happen at the movies. On-screen football coaches tend to be paragons of virtue. The movie that most sticks in my mind in this regard is an oldie, 1940’s Knute Rockne, All American. Today the movie is best remembered for Ronald Reagan’s portrayal of a real-life Notre Dame halfback, George Gipp, who – before dying young of a streptococcal throat infection -- makes an inspirational speech urging his teammates to “win one for the Gipper.” But the movie’s true star is Pat O’Brien, who plays the title character, a Notre Dame chemistry instructor who transforms the game of football with his inventiveness and his leadership skills. He invents the forward past, and inspires his Fighting Irish teams (composed of good men and true) to glory before dying at the age of 43, in 1931. Ironically, he was en route to serve as a technical advisor for a feature film called The Spirit of Notre Dame when his plane went down in a Kansas field.

Pat O’Brien’s Knute Rockne is a totally good guy (as in real life he apparently was). A much more recent true football story also boasts a good-guy hero. I’m talking about Remember the Titans, released in 2000, but chronicling a memorable series of events from 1971. The place was Alexandria, Virginia, then in the throes of desegregation. African-American Herman Boone (Denzel Washington) is hired to replace a legendary white coach at the head of a newly integrated high school team. Predictably, there are clashes between black and white members of the squad, complicated by the fact that the original coach has reluctantly agreed to serve as Washington’s assistant. But, happily, everyone learns to work together, despite the bad behavior of biased officials, for the greater glory of T.C. Williams High School,

USC has enjoyed a great deal of football glory, but the Steve Sarkisian era will not be on its highlights reel. Despite the real-life drama involved, a movie about a football coach with a drinking problem will probably not be on a studio’s roster anytime soon. This is especially true because USC has long had a cozy relationship with Hollywood. Its fabulous film school buildings are financed by some of the industry’s finest (Lucas, Spielberg, Ron Howard), and I doubt they’d smile on a story that cast university personnel in a negative light. I’ve discovered there WAS at least one Hollywood movie that focused on a football coach from hell. But College Coach, starring Dick Powell as a conniver who’ll do anything to win games, was made all the way back in 1933. I don’t see it being updated anytime soon.

Published on October 23, 2015 09:34

October 20, 2015

Broadway Musicals Go Hollywood, and Vice Versa

A young man I know, one who’s determined to make a life as a writer of stage musicals, published on an online site called StageBuddy a strong piece of advice on how to improve today’s musical theatre scene: “Stop trying to adapt blockbuster movies into blockbuster [stage] shows. There are tons of original, audience-friendly ideas out there -- they just need a producer's confidence to bring them to life.”

He’s right, but if you skim the list of what’s hot on Broadway, you’ll discover how much of it is derived from material with a movie connection. At one time, Hollywood looked to Broadway as a source of major musicals that could be successfully translated to the screen. Check out the Sixties and early Seventies, when some of the biggest movie hits included big-budget adaptations of My Fair Lady, The Sound of Music, Oliver!, Fiddler on the Roof, and Cabaret. Today, the occasional stage musical gets the screen treatment, but usually without much success. Case in point: Clint Eastwood’s muddled attempt to make a movie out of the delightful stage hit, Jersey Boys, the story of Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons. Also in 2014, Rob Marshall and an all-star cast worked hard to film the challenging once-upon-a-time musical, Into the Woods. There are some lovely moments in this movie adaptation of Stephen Sondheim’s intertwined fairytales, but no one would call it a blockbuster. About the yowling 2012 screen version of Les Misérables, the less said the better.

When I was last in New York, it was remarkable how many Broadway musicals had taken their inspiration (and much more) from original film versions of the material. I’m thinking, of course, of such current Disney extravaganzas as The Lion King and Aladdin, as well as recent hits Mary Poppins and Beauty and the Beast. Also on today’s Broadway roster are stage musical adaptations of An American in Paris, Finding Neverland, School of Rock, and The Color Purple. Sometimes these Hollywood-meets-Broadway transitions inspire bold new staging ideas, like those director Julie Taymor brought to The Lion King , using the magic of puppetry to replace Disney animation. But generally audiences who choose to see, let us say, the stage musical version of Legally Blonde (which ran on Broadway from 2007 to 2008 before doing extensive touring) want a fairly exact copy of everything they loved in the film. Which requires less creativity than a form of cloning.

My son Jeff Bienstock was recently fortunate enough to have a new stage musical on display at the National Alliance for Musical Theatre’s annual New York festival. Legendale, for which Jeff wrote book and lyrics (with Andrea Daly supplying the music) takes the audience into the wacky world of fantasy video games, featuring trolls, ogres, bog-monsters, and cow-maidens. These characters are set against such real-life types as a bored IT guy and a mousy office temp. The NAMT festival also presented six other totally original musical works: I saw a film noir musical with elements of old radio drama, an ominous piece about dead souls arising from a Southern cornfield, and an end-of-the-world phantasmagoria whose leading characters included Marie Antoinette and the inventor of the hot-air balloon. The only plot that was not wholly a product of its writers’ imagination was a hip-hop do-over of Shakespeare’s Othello. In other words, in the rarefied realm of musical theatre, originality is hardly dead. Today on Broadway audiences are cheering a rap musical based on the life of Alexander Hamilton. So let’s hope originality continues to flourish on the musical stage, whether or not movies are involved.

Published on October 20, 2015 14:54

October 16, 2015

Keeping the Hills Alive with “The Sound of Music”

We all know how The Sound of Music opens, right? It starts with a helicopter shot of Julie Andrew on an Austrian mountaintop, spinning ecstatically in place as she carols, “The hills are alive . . .” Yes, that’s the oh-so-familiar movie version, one of the all-time box-office champions. But The Sound of Music was first a hit Broadway show, starring Mary Martin and Theodore Bikel. Last night I saw a Broadway-bound revival, which brought back memories of years gone by, when – at a huge barn-like auditorium called the Los Angeles Philharmonic Hall – I first encountered The Sound of Music, with Florence Henderson at the head of a touring production.

The stage version of The Sound of Music, based on the story of Maria von Trapp and her musical brood, starts not with a helicopter shot but with a chorus of nuns singing a joyful “Alleluia.” (My father, who did not have much use for nuns, once wondered at this point whether he’d stumbled into the wrong show.) Needless to say, some of movie’s greatest charms are missing from the stage version. On stage, mountains have to be portrayed by painted backdrops, and you can’t show that gaggle of little von Trapps biking down country lanes, and rowing on country lakes. So the joy in nature felt by the leading characters must be accepted . . . yes! . . . on faith.

Still, I was fond of the stage version because it seemed franker about the other side of the mountain, the ongoing Nazi threat that balances the sweetness and light at the show’s core. The movie does retain both Captain von Trapp’s wealthy, worldly fiancée and his impresario friend who makes a virtue of expedience. But in the movie adaptation, their two songs have been removed. “How Can Love Survive?” is a cynical ode to romance among the very rich. “There’s No Way to Stop It” is a comic ditty dedicated to the wisdom of celebrating the men in charge, whomever they might be, in order to save one’s own skin. This second song makes perfect sense in a tale about leaving one’s homeland rather than capitulating to the dictates of the Nazi Anschluss. Beneath the song’s apparent light-heartedness, it’s a bold statement, and I thoroughly enjoyed hearing it again.

This new production, which began in L.A., does right by the political forces that are gathering. A particularly vivid touch involves the climactic musical competition in which the Trapp Family Singers appear. When they take the stage in their quaint dirndls and lederhosen, the backdrop behind them is a huge set of red banners flaunting the Nazi swastika, which was more than enough to send shivers down my spine. Casting works well too. Director Jack O’Brien points out in a program note that when Mary Martin starred as Maria on stage, she was 47 years old. Julie Andrews, cast in the movie after becoming America’s sweetheart in Mary Poppins, was nearly 30. The new Maria is (heaven help us!) a college sophomore in her first big role. Kerstin Anderson, just 21, is tall and gangly, with a lovely voice and lots of infectious spunk. She’s believable as a postulant in an abbey, and we can totally buy her falling for Captain von Trapp (Ben Davis), who’s played a bit younger than usual and looks something like a bearded Ryan Gosling. The moppets (envied, I’m sure, by every kid in the audience) are well differentiated. And Ashley Brown, as the Mother Abbess, raises the rafters with “Climb Every Mountain.” The Sound of Music sounds very good indeed.

Published on October 16, 2015 07:00

October 13, 2015

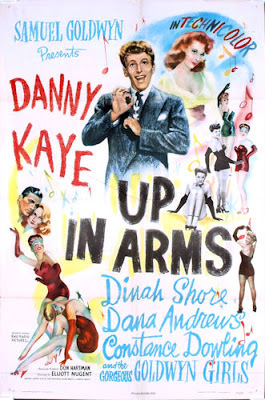

"Up in Arms": A Peach of a Pair at the Movies

When your mother is a packrat, you find yourself with all sorts of treasures. The letters my parents exchanged during World War II, when my G.I. father was stationed in a finance office in Indianapolis while my mother served as a social worker in Omaha, showed how important a role movies played in keeping their morale high during their enforced separation from one another. Both went to the movies constantly in their off-hours: motion pictures were cheap entertainment, could provide inspiration or a few laughs, and had the extra advantage of being shown in theatres that were “refrigerated,” in the terminology of the day. There’s one family story about Omaha, a sweltering city in mid-summer. Given that few residences were air-conditioned, staying home was out of the question. And so my parents—when together--were always seeking out movies that struck their fancy. They loved to laugh, which is why comedies were always their first choice. In the summer of 1944, that meant Danny Kaye in Up in Arms: they saw this laugh-fest about a hypochondriac who gets drafted into the Army at least seven times in the space of a few weeks. As a result, they learned all the musical numbers (including the zany Lobby Number) by heart -- and, years later, so did I. (When it’s cherry blossom time in Orange, New Jersey, we’ll make a peach of a pair . . . . but I digress.)

When your mother is a packrat, you find yourself with all sorts of treasures. The letters my parents exchanged during World War II, when my G.I. father was stationed in a finance office in Indianapolis while my mother served as a social worker in Omaha, showed how important a role movies played in keeping their morale high during their enforced separation from one another. Both went to the movies constantly in their off-hours: motion pictures were cheap entertainment, could provide inspiration or a few laughs, and had the extra advantage of being shown in theatres that were “refrigerated,” in the terminology of the day. There’s one family story about Omaha, a sweltering city in mid-summer. Given that few residences were air-conditioned, staying home was out of the question. And so my parents—when together--were always seeking out movies that struck their fancy. They loved to laugh, which is why comedies were always their first choice. In the summer of 1944, that meant Danny Kaye in Up in Arms: they saw this laugh-fest about a hypochondriac who gets drafted into the Army at least seven times in the space of a few weeks. As a result, they learned all the musical numbers (including the zany Lobby Number) by heart -- and, years later, so did I. (When it’s cherry blossom time in Orange, New Jersey, we’ll make a peach of a pair . . . . but I digress.)Sadly, I’m cleaning out my mother’s home these days. (She died almost a year ago, at age 96.) Among the many souvenirs she saved was a professional caricature of herself done on May 5, 1944, on the back of a menu at L.A.’s swankiest nightspot, the Cocoanut Grove. My parents were obviously celebrating being home on a brief leave by going out on the town. The Cocoanut Grove, located in the famous Ambassador Hotel, was well known for its jungle décor, and for being a playground for Hollywood stars. My folks were Depression-era kids, so the prices must have seemed extravagant. Like the Dinner de Luxe, featuring an appetizer, soup, an entrée like chicken or leg of lamb, salad, dessert, and demi-tasse, for a whopping $3.00. And you also got to see a stage show featuring some of the day’s hottest musical acts.

Needless to say, the Cocoanut Grove was featured in many films. On February 29, 1940, the Academy Awards were staged there, with Bob Hope as emcee. In 1967, the Cocoanut Grove didn’t make it into The Graduate. But the scenes supposedly set in the “Taft Hotel” lobby (where desk clerk Buck Henry flummoxes Benjamin Braddock by asking, “Are you here for an affair, sir?”) were shot in a cordoned-off section of the Ambassador’s own spacious entryway. Just one year later, in the wee hours of June 5, 1968, the Ambassador Hotel found another, much sadder, form of notoriety when Democratic presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy—having just won the California primary—was gunned down by Sirhan Sirhan. The hotel was Kennedy’s campaign headquarters. Having delivered a victory speech in one ballroom, he was passing through a hotel kitchen on his way to another venue, when Sirhan fired three times at close range. He died following surgery.

It’s eerie to remember that I was there – one of thousands waiting to hear a victory speech that never came. My parents were present too. The Ambassador Hotel seemed far less glamorous after that tragedy. It closed down early in this century, and was replaced with a school complex that bears Kennedy’s name. A planned documentary about the Ambassador never quite happened.

Published on October 13, 2015 09:45

October 9, 2015

Kevin Corcoran and Catherine Coulson: Two We Lost Too Soon

Say it ain’t so! Movieland has lost some good people lately, workaday actors who’ve also made a difference in other fields. I was startled to learn about the passing of Kevin Corcoran, who was claimed by cancer when he was just 66. I will always remember him as the impish Moochie in a number of Walt Disney productions, including an early Mickey Mouse Club serial called “Adventures in Dairyland” (definitely not Walt’s most exciting idea). He also played a kid called Moochie in a wildly popular comedy feature of the Fifties, The Shaggy Dog. In that film, he was the tagalong younger brother of Disney regular Tommy Kirk. Kevin and Tommy were also cast as brothers in a Civil War tearjerker, Old Yeller, as well as in Swiss Family Robinson and two other Disney features.

Corcoran was born into an acting family: his sister Noreen co-starred for years on Bachelor Father (1957-1962), and there were six other little Corcorans in the business. Fortunately, acting seemed to be a low-pressure activity in his household, something rare for showbiz kids. He himself stopped performing in the late 1960s, when he realized he knew more than the production team. After graduating from college, he returned to Disney to work behind the scenes, as an assistant director and ultimately a producer. One of his non-Disney shows was the long-running Angela Lansbury series, Murder, She Wrote. Before becoming ill, he worked on two very un-Disney projects for FX: The Shield and Sons of Anarchy.

It’s refreshing to read about a child star who became a responsible adult with a stable career and a long, loving marriage. His screen brother, Tommy Kirk, had a much more difficult time. Though a big success on TV and in films, he struggled with interpersonal relationships, and his knowledge that he was gay—in a highly conservative era—made life difficult. There were major drug problems before he figured out how to turn his life around. Given his years of excess, it’s ironic that he’s alive and well, and poor Kevin Corcoran is gone.

I first became aware of Catherine Coulson while watching the Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s wonderful production of Stephen Sondheim’s Into the Woods. Her non-speaking performance as Milky White, a rather pathetic dairy cow, was for me a comic standout. It was while doing this role last December at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills that she was diagnosed with cancer. My friend Sherril Wood, who played flute in that production, has told me how lovingly the other cast members rallied around her in her hour of need.

It was not until Coulson passed away two weeks ago that I discovered the scope of her showbiz career. She worked for years as a Hollywood camera assistant: one of her credits was Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Back in 1977 she’d served on the camera crew of David Lynch’s Eraserhead, in which her then-husband Jack Nance got top billing. She and Lynch developed a close friendship, which led to him creating for her the memorable role of the Log Lady on his landmark TV series, Twin Peaks. The Log Lady’s mysterious clues and devotion to a large, ungainly piece of lumber became a hallmark of the oddball series, to the point where the reruns on Bravo added her cryptic introductions to the various episodes. She was due to be part of a revived series that was in preparation in 2015. When news of her death surfaced, Lynch was quoted as saying, “Today I lost one of my dearest friends.”

Rest in peace.

Published on October 09, 2015 09:49

October 6, 2015

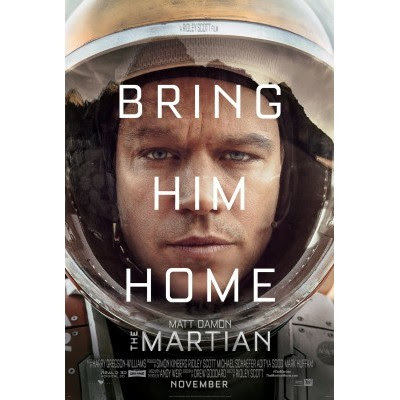

“The Martian” and Randii Wessen – Not Lost in Space

No surprise that this past weekend Ridley Scott’s (and Matt Damon’s) The Martian topped box-office charts. Given the widely publicized discovery last week of water on Mars, it almost seems as though NASA were staging a promo for the new film.

I certainly don’t accuse the nation’s top scientific thinkers of being on Hollywood’s payroll. But it’s true that aerospace scientists and those who love them are rooting for The Martian’s success. There’s nothing like a terrific outer-space movie to inspire public excitement about space exploration. In fact, Andy Weir, the author of the novel on which the film is based, was recently an honored speaker at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where engineers and scientists were thrilled to hear about a story with a serious science bent.

One JPL’er with more than a casual interest in The Martian is Randii Wessen, who has a most unusual sideline. Randii holds a bachelor’s degree in physics and astronomy, a master’s in aerospace engineering, and a PhD in operations research. He’s been in the field for thirty years, and now boasts the mysterious title of Team Lead Study Architect at the JPL Innovation Foundry. He’s also active in the JPL speakers’ bureau, which has sent him as far as Australia. (Hey, it’s not Mars, but it’s still a long way away.)

In his spare time, Randii is associated with something called The Science and Entertainment Exchange. This organization was founded by filmmaker Jerry Zucker in conjunction with the National Academy of Science. Remarkably, it provides free resources to any screenwriter who wants to ensure scientific accuracy. If you’re a TV writer who needs to know all about crystal meth production (for professional reasons, of course), this is a good place to come.

In addition to fielding questions from young writers, Randii has lucked into a few paying gigs. Two are with Disney: he has consulted on both an animated series called Miles from Tomorrowland and a TV movie known as Invisible Sister. It’s his mission, he feels, to make sure that nothing in these fanciful shows violates a natural law. On Miles from Tomorrowland, in which characters travel through space, he wants to make certain the writers understand the concept of gravity as it applies to the moon. For one episode, the writing staff suggested that the Dad-character put anti-gravity powder into pancakes, so that they float. Randii’s query: why don’t the eaters of the pancakes float too?

Like most scientists and engineers, Randii had his imagination sparked at an early age by sci-fi movies. He once thrilled to Lost in Space, E.T., and Forbidden Planet. Now he appreciates movies that are accurate in terms of physics: Apollo 13, Contact, even 2001. Regarding recent outer-space flicks, he has mixed emotions. He found Gravity, for instance, “beautiful and exciting.” It made him wince, however, when astronaut Sandra Bullock propelled herself through space with blasts from a fire extinguisher, since realistically she would not be able to control her direction as she does on screen.

Does Randii aspire to write his own science-fiction screenplay? He admits that at school he was a solid C student in English. Still, as an unexpected second twin, he was named after a Remington Rand typewriter. (It’s a long story.) And he’s not short on imagination. He wonders about what sunrise and sunset would be like on Uranus, whose tilted axis suggests nights that are 42 years long. On Titan, so cold that its water would be rock-hard, he pictures ethane gasses producing “slow rain.”

So maybe there’s a writer in him just waiting to come out.

This year’s JPL open house, a hands-on introduction to the wonders of space, will take place on October 10-11. It’s free of charge, and fun for all.

Published on October 06, 2015 12:23

October 2, 2015

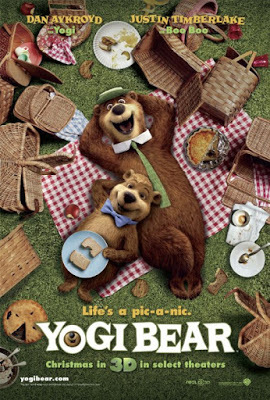

Yogi Berra Meets Yogi Bear

The loss last week of baseball’s Yogi Berra deprived us of a legendary athlete and a remarkable human being. His inspired mangling of the American language in itself will ensure that he never be forgotten. As he himself put it, “I never said most of the things I said." Still, you’ve got to love someone who’s at least capable of coining such phrases as “The future ain't what it used to be,” as well as “Half the lies they tell about me aren't true” and the evergreen “Nobody goes there anymore. It's too crowded.” There’s a kind of rough wisdom in Yogi Berra-isms, like “In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is.”

Beyond this, Yogi Berra inspired one of Hollywood’s most beloved characters. Yes, I’m talking about Yogi Bear. He was created by the Hanna-Barbera animation team in 1958, as a supporting player on the Huckleberry Hound TV cartoon series, but became so popular that he got his own show three years later. On his decidedly family-friendly series, Yogi hangs out in Jellystone Park with his young sidekick, Boo Boo, stealing picnic baskets, tussling with Park Ranger Smith, and frequently proclaiming himself “smarter than the av-er-age bear!" Over the years he’s appeared in scores of TV shows, animated features, and made-for-TV movies. As recently as 2010, he was featured in a 3-D film, and also starred in a Nintendo video game.

To my surprise Yogi Berra, the Yankee legend, was not thrilled by the introduction of Yogi Bear. If Wikipedia is to be trusted, Berra actually sued Hanna-Barbera for defamation, but lost the case when the other side somehow convinced the judge that the similarity of the two names was pure coincidence. Hey, who wouldn’t want to be the inspiration for a lovable cartoon character? Personally, I suspect I’d be flattered. But of course, as Yogi Berra himself (maybe) said, “There are some people who, if they don't already know, you can't tell 'em.”

At the time Yogi Bear first appeared, Hanna-Barbera was a new company, founded in 1957 by two former MGM animation directors who had once created Tom and Jerry. Yogi’s success soon led to a raft of other Hanna-Barbera TV shows. The ones I remember are from the Sixties. The Flintstones, which surfaced in 1960 as a primetime series, was a sitcom with a difference: its transformation of suburban family life into pre-historic days was so cleverly realized that it amused kids and parents alike. And then, having conquered the caveman era, Hanna-Barbera took a similar nuclear family into the future with The Jetsons, another show made with real wit (but certainly not the kind of snarkiness we expect in TV animation today).

As an entertainment journalist I visited Hanna-Barbera only once, while writing an article on voice actors. It was my pleasure to watch a recording session (for something called The New Shmoo Show) during which talented adults played a fascinating game of let’s pretend. Here’s what I wrote in Performing Arts magazine about the much-admired Frank Welker, who starred as Al Capp’s lovable Shmoo character: “Like many voice people, Welker immerses himself in a character so totally that he punctuates his lines with emphatic body language. While he chortles, squeaks, and makes remarkable ‘greeble’ sounds, his hands saw the air and his face contorts into truly Shmoo’ish expressions.”

Watching Frank Welker perform was a delight. And I would have been delighted to meet Yogi Berra too. I’ll sign off with one final all-too-apt Berra-ism: “You should always go to other people's funerals; otherwise, they won't come to yours.”

Published on October 02, 2015 10:34

September 29, 2015

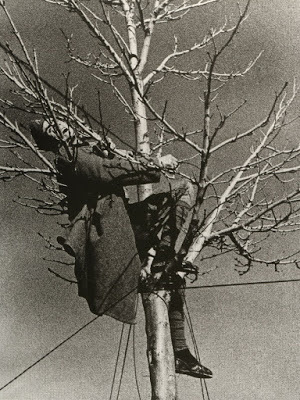

The Rain in Spain: “Hotel Florida”

Robert Capa's photo of a dead man in a treeThe Iberian Peninsula is in the news again, via the parliamentary election in Catalonia that is sending a signal of the region’s desire to be independent of Spain. And the whole world has been shaken by the photos of a Syrian toddler lying dead on a Turkish beach, one victim of the current refugee crisis. Both the news accounts and the photos have sent me back to Hotel Florida, Amanda Vaill’s fascinating 2014 account of “truth, love, and death in the Spanish Civil War.” Vaill’s book has a lot to say about the role of both movies and still photography in shaping popular opinion about a conflict that turned out, sadly, to be a rehearsal for World War II.

Robert Capa's photo of a dead man in a treeThe Iberian Peninsula is in the news again, via the parliamentary election in Catalonia that is sending a signal of the region’s desire to be independent of Spain. And the whole world has been shaken by the photos of a Syrian toddler lying dead on a Turkish beach, one victim of the current refugee crisis. Both the news accounts and the photos have sent me back to Hotel Florida, Amanda Vaill’s fascinating 2014 account of “truth, love, and death in the Spanish Civil War.” Vaill’s book has a lot to say about the role of both movies and still photography in shaping popular opinion about a conflict that turned out, sadly, to be a rehearsal for World War II.At the heart of Vaill’s book are three romantic couples. Arturo Barea and Ilsa Kulcsar came together unexpectedly when both were serving as press officers on behalf of the Spanish Loyalist cause. Robert Capa, originally from Hungary, and Gerda Taro, born in Poland, were war photographers on the lookout for the next big story. They gave their all to the Loyalists, and ultimately Taro gave her life. Ernest Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn, both of them journalists and authors, were Americans who loved Spain and craved adventure. Hemingway, looking for a way to be involved in the conflict, found it in the making of a pro-Loyalist film, The Spanish Earth.

All of these characters passed, at one time or another, through the lobby of Madrid’s Hotel Florida, which explains the book’s title. Vaill paints a vivid picture of Spain’s capital as a place where it seemed “as if the war were a movie on a distant screen.” Early in the conflict, life in Madrid goes on as usual: at the Genova movie palace at Plaza de Callao, you could buy a ticket to see Lionel Barrymore performing in David Copperfield. Hemingway, chronicling the war for a global audience, noted that “readers in New York, and Chicago, St. Louis, and San Francisco, would never believe you could be in a war zone where there were bars and functioning movie theaters and shops selling perfume; they needed to smell cordite and hear guns.” Later, though, Madrid too suffered bomb attacks. The Paramount Theatre near Hotel Florida took a direct hit, one that damaged the giant sign advertising Chaplin’s Modern Times.

Out in the countryside, Robert Capa and Gerda Taro were risking their lives to capture images of fallen soldiers, weeping women, and murdered children. Early in the war, Capa had participated in staging faked war footage, and he would do so again years later on behalf of The March of Time. But for the most part he was deeply committed to photography as a form of honest recording of reality at its most raw. His motto: “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” The quintessential combat photographer, he died in 1954 in Vietnam, while shooting photos for Life magazine.

Hemingway, while playing at documentary filmmaking, was involved with creatively shaping material that made the causes of the Spanish Civil War seem simple and direct. Later, dramatic devices were added, like artificial sound effects and the reading of a purely fictional letter. Back in the U.S., screenings of The Spanish Earth were hosted by such Hollywood celebs as Joan Crawford, John Ford, and Darryl Zanuck. Lillian Hellman sponsored a similar gathering at the home of Frederic March. Hemingway himself made a speech at Carnegie Hall, and through Martha Gellhorn’s contacts got his film into the hands of Eleanor Roosevelt. Thus did Hemingway use his movie-star status on behalf of the Loyalist cause.

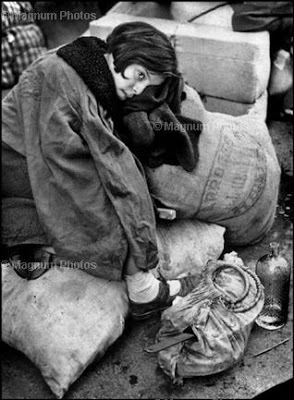

Capa photographs a young refugee

Capa photographs a young refugee

Capa's most famous photo of a dying soldier

Capa's most famous photo of a dying soldier

Published on September 29, 2015 16:51

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers