Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 106

September 25, 2015

. . . We All Scream for Jamie Lee Curtis

The debut this week of Fox’s Screen Queens series reminds me how much I love Jamie Lee Curtis. It’s not that -- despite my Roger Corman past – I’m a huge fan of horror films in which pretty girls in their undies try to fend off rapists and killers. (Really, isn’t enthusiasm for these flicks largely a guything?) Yes, Jamie Lee got her showbiz start as Laurie Strode, the good girl who survived Halloween, and then went on to star in such chillers as Halloween II, The Fog, and Prom Night. But it’s what she’s done since that impresses me.

In one way, Jamie Lee was predestined for stardom. After all, her mother was perky blonde Janet Leigh, who was featured in scores of films in the 1950s and thereafter. I think of her in such light romantic comedies as My Sister Eileen and Bye Bye Birdie. But of course her best-known role was that of the original scream queen, Marion Crane, who took a deadly shower in Hitchcock’s Psycho. Jamie Lee’s father, Tony Curtis, was also a Hollywood superstar, both as a glamour-boy and as a serious actor in films like The Defiant Ones.

Once she’d made her mark in horror films, Jamie Lee started looking for cinematic respectability. Of all places, she ended up at Roger Corman’s New World Pictures, where Amy Holden Jones wanted to follow up her Slumber Party Massacre with something completely different. Jones wrote and directed Love Letters (1984), a romantic drama in which a young woman is inspired by her mother’s long-ago example to start a torrid affair with a married man. True to form, Corman demanded more nudity than was contained in Jones’ original script. She and Jamie Lee had no choice but to comply. Surprisingly, the eventual New World Pictures poster (which I recall on display in our office entryway) was the opposite of sleazy. And Jamie Lee moved on to bigger and better things.

Since then her films have included sparkling comedic performances in A Fish Named Wanda (1988) and True Lies (1994), for which she won a Golden Globe. The latter film took advantage of her persona as an apparently average suburban wife and mom who turns out to have a secret yen for adventure. Her ready-for-anything style also enhanced the 2003 screen adaptation of Freaky Friday, in which she and daughter Lindsay Lohan switch bodies.

I love these last two films because they “prove” that middle-of-the-road women, well past the sexpot stage, can still have hidden depths. That’s something Curtis has been proving in real life as well. She’s been married since 1984 to her one and only spouse, the hilarious Christopher Guest of Spinal Tap and Best in Show fame. Though she actually became a British baroness when Guest came into the title of Baron Haden-Guest in 1996, they apparently have a modest lifestyle. Together they’re raising their two children in (yes!) Santa Monica, though I admit I’ve never seen them wandering around town. While in child-rearing mode, she wrote a number of well-received kids’ books, including one, Today I Feel Silly, and Other Moods That Make My Day, that spent ten weeks on the New York Times bestseller list.

But what I love most about Jamie Lee Curtis is her honesty about herself and her failings. Seeking to debunk the myth of Hollywood glamour, she actually posed for MORE magazine in 2002 wearing nothing but her underwear. Unadorned, unretouched, she was showing the world what a forty-year-old looks like, sans Hollywood magic. She’s earned every one of her now-abundant grey hairs. You go, girl!

Published on September 25, 2015 11:13

September 22, 2015

Americanah-- What Happens When Migrants Move In

The migrant crisis in Europe keeps growing. Today alone, some 20,000 refugees fleeing from Middle Eastern conflicts are trying to pass through Austria. Like the rest of the world, I have no smart ideas on how to solve a problem of this magnitude. But there’s no question that the fate of displaced persons has been a part of our global history from time immemorial.

Which means, of course, that scores of movies have been made about people who cross borders in time of duress, and end up finding themselves strangers in a strange land. We Americans are, whether or not we’d like to admit it, a nation of immigrants, and for the moment I’ll confine myself to films that detail the stresses and strains of coming to America.

Yes, Coming to America is -- as those with long memories know -- the title of an Eddie Murphy comedy about an African king who visits our shores to find a bride. (It was also the subject of a precedent-setting lawsuit by humorist Art Buchwald, who proved in a court of law that Paramount Pictures had lifted his original script treatment, without compensation.) But I’m not concerned today with the notion of visits by foreign potentates. I want to confine myself here to movies in which desperate people cross the ocean in search of a new life.

One such film was made by the great, though controversial, Elia Kazan, who was born in what was then called Constantinople, Turkey, of Anatolian Greek parents. His America America (1963), based on his own novel, is a loose dramatization of the life of his uncle, who traveled from Anatolia to Constantinople (now Istanbul) to escape the grinding poverty of his homeland. Along the way, the hero loses his nest egg, survives some life-or-death encounters, and changes his destination. It’s not until the very end of the film that he sees the Statue of Liberty rise before him in New York harbor.

I’m a great fan of the charming 1975 indie, Hester Street, in which an arrival in Manhattan makes all the difference in the life of a Jewish immigrant family from Eastern Europe. Jake has preceded his wife to the Goldene Medina (Yiddish for “Golden Land”) by several years, in order to establish a toehold in his new country. By the time wife and son arrive, Jake’s a stylish gent who’s enjoying his new freedoms on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Poor Gittel, with her old-world ways, quickly feels she’s not entirely welcome. How she handles this sticky situation is what the movie is all about.

Much more recently, there’s Amreeka (2009), the rare Palestinian movie that is less about Middle Eastern political issues than about adapting, both joyfully and painfully, to life in the United States. This is another film I can wholeheartedly recommend.

Which brings me to a major 2013 novel I suspect will make an important movie. It’s called Americanah , by award-winning Nigerian émigré Chinamanda Ngozi Adichie. Its two main characters -- bright, middle-class young people -- leave their homeland, he for England and she for the United States. It’s a love story, but also a tale about the meaning of blackness in countries where skin color helps determine destiny, for better or for worse. I’ve heard Lupita Nyong’o, Oscar-winner for Twelve Years a Slave, has signed on for a role that would capitalize on her gloriously ebony complexion. Once upon a time, the elegant and talented Nyong’o would have been wholly shut out of Hollywood glamour roles. Now she’s the new face of Lancôme cosmetics, and let’s hope the sky’s the limit.

Published on September 22, 2015 14:59

September 18, 2015

Of Alarm Clocks and Brilliant Young Minds: It’s Not Easy Being Smart

One of the big stories lately has been the case of Ahmed Mohamed, a fourteen-year-old Texas schoolboy with a passion for technology. When he showed off to his teacher an alarm clock he’d made himself, a thingamajig full of coils and wires, she called the cops. Next thing he knew, he was being hauled off to jail in handcuffs, accused of trying to cause panic by assembling a phony bomb.

It didn’t help, of course, that he was a dark-skinned boy whose name identified him as a religious Muslim. Even his NASA t-shirt couldn’t save him from being considered a junior-grade terrorist. Now that the police have cleared him, he’s still suspended from school. Of course the ACLU has gotten involved. So have President Obama and Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, both of whom have put out the welcome mat for this promising young science whiz.

Clearly, being smart and geeky is a mixed blessing.

I took away the very same message from a new British film. It was originally called X +Y, but is being released (at least in the U.S.) as A Brilliant Young Mind. I suspected at first that we’re supposed to be lured into theatres by the similarity between this title and that of Ron Howard’s Oscar-winning drama about a grown-up mathematical genius with severe mental issues. But in fact this movie is the first feature of Morgan Matthews, the filmmaker behind the 2007 BBC documentary Beautiful Young Minds, which followed the fate of the British team competing in the 2006 International Mathematics Olympiad.

Most movies about competitions focus on the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat. Think of, for instance, another British film: Chariots of Fire. I also remember Spellbound (2002), a documentary that managed to find high drama in America’s 1999 National Spelling Bee. I don’t know the details of Matthews’ math team documentary. But I’m aware that in one of the contestants, Daniel Lightwing, Matthews found a young boy whose gifts and challenges have made him well worth portraying in a fictionalized context.

Matthews’ fictive hero, Nathan Ellis, resembles Daniel Lightwing in that he clearly belongs somewhere on the Autism spectrum. He has, for instance, a thing for prime numbers, and will only eat prawn balls when they come in groups of seven. His extreme social awkwardness has only been exacerbated by a family tragedy, from which his good-hearted mother (the always affecting Sally Hawkins) is desperately trying to rescue him. Nathan is played by Asa Butterfield, who was the beautiful little boy with enchanting blue eyes in Martin Scorsese’s Hugo. Now tall and gangly, he’s thoroughly convincing as an overgrown kid who cannot relate to people but has a brilliant comprehension of what the British call “maths.” A school teacher with problems of his own (Rafe Spall) discovers his mathematical gifts and coaches him for eventual acceptance on the British national team. This leads to a trip to Taipei and a close encounter with some formidable young math whizzes on the Mainland Chinese team.

I won’t give away what happens, but one of the joys of A Brilliant Young Mind is that it’s about people far more than it is about math. (Which is a good thing, because the intricate math problems solved in this film are far beyond my comprehension.) Let’s just say that victories sometimes can be found in unexpected places. I once knew a young boy so out of step with his classmates that they nicknamed him UFO. He grew up nicely, and I trust Nathan Ellis (and Daniel Lightwing) will do so too.

Published on September 18, 2015 10:12

September 15, 2015

Twinkle, Twinkle, Dickie Moore (What it's like to be a child star in Hollywood)

I don’t really know the film work of Dickie Moore, who died September 7 at age 89. Though the chubby-cheeked little boy got his start in silent movies, Moore’s heyday was the Depression era. He appeared in 19 motion pictures in 1932 alone. The following year, at the age of 6, he played the lead in a film adaptation of Dicken’s Oliver Twist. He was Marlene Dietrich’s young son in Blonde Venus, and shared the screen with Barbara Stanwyck in So Big, Walter Houston in Gabriel Over the White House and Spencer Tracy in Man’s Castle. By the age of twelve, he was a has-been, but later had the distinction of giving another former child star, Shirley Temple, her first screen kiss.

Moore was the rare child star of Hollywood’s Golden Age who managed to get a college education. After serving in World War II, he studied journalism at Los Angeles City College, then used his writing skills in running a public relations firm, Dick Moore and Associates, that lasted four decades. In 1984, he published a book I consider a classic. Its jaw-dropping title: Twinkle,Twinkle, Little Star (But Don't Have Sex or Take the Car). Far more than a memoir, this is Moore’s wide-ranging exploration of what it was like to be a top child actor in his own era. For the book, he interviewed many of his peers, including Jackie Coogan, Shirley Temple, Mickey Rooney, Jane Withers, Roddy McDowell, Margaret O’Brien, and Natalie Wood. All agreed that child stardom is an unnatural state. It may have its pleasures, but it leaves one ill equipped to enter the adult world.

The child stars of Moore’s generation tended to shoulder the burden of being their families’ sole means of support. Which meant that in a professional sense they needed to grow up quickly, and to know how to behave in an adult environment. On the other hand, in an era that prized innocence, they were kept artificially young by their parents and their studios. Puberty was seen as the enemy, and these kids often remained ignorant of anything as basic as their changing bodies. And most were kept in the dark about money matters, too, with the result that they were frequently taken advantage of by conniving hangers-on. (Jane Withers, in this and so many other ways, was a happy exception.) There was always stiff competition from other young wannabe stars, which is why ambitious stage parents (like Shirley Temple’s mom) tended to isolate their little darlings from their peers. Child stars, by and large, were lonely. And despite their fame, they lacked a strong sense of personal self-worth. That’s why as they grew up they tended to marry young, and badly.

Not all successful child actors resented their parents. But many did . . . for good reason. Fathers were often out of the picture, or were so dispirited by having children who took on the role of family breadwinner that they pretty much vanished into the woodwork. Diane Cary (once adored as Baby Peggy) acidly called showbiz moms “the saber-tooth tigers of the Hollywood jungle.” Jane Powell, the adorable girl-next-door blonde, once considered her mother “my girlfriend, my confidante. . . . I am amazed I didn’t see through her as a child.” Looking back, she recognized her mother as a shrewd and calculating woman, who drove her father away on the grounds that he wasn’t good enough.

The interviews conducted by Moore for this book had one happy outcome. He and Powell married in 1988 (it was her fifth try), and stayed together until his death.

Published on September 15, 2015 19:31

September 11, 2015

Film Editor Sam O’Steen, A Man Who Could Tell a Joke

Yes, I’ve already written about Sam O’Steen. But I was so enthralled by his Cut to the Chase: Forty-Five Years of Editing America’s Favorite Movies that I can’t resist turning the spotlight on Sam once again. Of all the films he cut, The Graduate is probably his favorite, because “it was such a huge surprise that it hit the way it did when we really didn’t know what we had.” Sometimes, though, movies he considered masterpieces never did find their audience. Catch-22, the film made by Mike Nichols immediately after The Graduate, is one prime example.

Yes, I’ve already written about Sam O’Steen. But I was so enthralled by his Cut to the Chase: Forty-Five Years of Editing America’s Favorite Movies that I can’t resist turning the spotlight on Sam once again. Of all the films he cut, The Graduate is probably his favorite, because “it was such a huge surprise that it hit the way it did when we really didn’t know what we had.” Sometimes, though, movies he considered masterpieces never did find their audience. Catch-22, the film made by Mike Nichols immediately after The Graduate, is one prime example.Like all editors, Sam labored hard in the cutting room to make good films better. Sometimes, though, the job entailed salvaging a project that just didn’t work. Take the case of Dry White Season, a movie about apartheid that was shot in South Africa in 1989. The novice director was proud of her “vision,” but it didn’t translate onto film, and because the original editor had “butchered up all the main takes,” Sam was called in for an emergency doctoring job. He was presented with a roomful of footage, but absolutely no paperwork. Fortunately, he enjoyed the challenge of assembling outtakes, jigsaw-puzzle-style, into a coherent story. For instance,“I found this film that wasn’t even shot for the movie: the camera had just been running while this white boy and this black boy [young actors in the film] were playing together, fooling around with a ball.” Sam chose to run this footage over the main title sequence, “because that’s what the story was about, that they were friends, but they were supposed to be enemies.” He ultimately considered Dry White Season some of his very best work, “because it wasn’t a movie, and now it is.”

Then there was the time Sam lopped off an entire season. The 1999 film debut of writer-director Tony Bui was the first American movie shot in Vietnam since the Sixties. Originally called Four Seasons, it told four separate stories, set against appropriate times of the year. But the “Rainy Season” segment was tedious, and Sam chose to highlight the appealing love story of a cyclo driver and a hooker at the expense of less dramatic tales (like that of a sad poet, as well as ex-soldier Harvey Keitel’s search for daughter he’d left behind). The result was Three Seasons, which was honored at Sundance and became a minor art-house success.

Sam O’Steen had strong opinions on just about everything, like the introduction of computerized editing systems To him, computers were a mixed blessing. Yes, they speed up the editing process, and there’s no danger of ruining delicate film stock, so it’s much simpler to experiment now. On the other hand, because a computer is far easier to master than the old Moviola, everyone wants to get into the act. So the old days of the editor and director cutting in relative solitude are becoming a thing of the past, as producers and studio execs vie to take charge of the finished product.

At the end of this book, wife Bobbie (a veteran editor herself) asks Sam what kind of person makes a good editor. His answer is surprising: “Someone who can tell a joke.” Why? “Because the timing is right and he tells just enough.” Naturally, other skills are useful too, like an ability to be organized, to work independently, and to have total concentration on the task at hand. It’s important to be secure in your opinions, without having a need to show off. And you should recognize what’s important and what’s not. Sam’s favorite expression? “Fuck ‘em.”

Published on September 11, 2015 12:49

September 8, 2015

Cutting Corners With Film Editor Sam O’Steen

Anyone who loves The Graduate admires the work of Sam O’Steen. He was the film editor who gave us such remarkable images as Benjamin Braddock sliding onto a swimming pool raft that suddenly becomes the body of Mrs. Robinson in bed at the Taft Hotel. In the course of a forty-five year career, O’Steen edited twelve films for the late, great Mike Nichols. Nichols encouraged him to be on the set during filming, so he could make suggestions that aided his work in the editing room. Here’s one more of his unique contributions: instead of simply intercutting between the nude Mrs. Robinson and the reactions of a very startled Benjamin, Sam juxtaposed quick flashes of her undraped body with an elaborate triple-take (Dustin Hoffman repeatedly whipping his head around). In his enlightening 2001 book, Cut to the Chase , O’Steen explains this as a sample of subliminal editing. He credits Sidney Lumet with pioneering this approach in The Pawnbroker; he himself successfully used it in Nichols’ Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf before trying it again in The Graduate. It’s not a logical moment: Ben’s eyes don’t match up with the body parts he’s glimpsing with such astonishment. Instead, O’Steen is following the principle of “cutting for performance, for the build-up of Benjamin’s panic.”

His work with Mike Nichols is only one facet of O’Steen’s career, which spanned the years 1961 to 1999. He also edited such classics as Cool Hand Luke, Rosemary’s Baby, and Chinatown. As a director, he was Emmy-nominated for Queen of the Stardust Ballroom (1976), starring Maureen Stapleton as a widow who finds a new lease on life through ballroom dancing. But though he was still directing as late as 1985, the editing room continued to be his real home. Fortunitiously, it led him to a long, happy marriage to a fellow editor with whom he had four daughters. Cut to the Chase is as much Bobbie O’Steen’s book as it is that of Sam himself. It’s basically a Q & A in which she quizzes him about every facet of his career. The fact that she knows the field and is intimately familiar with Sam’s best stories means that the answers she elicits are well worth hearing. The book is not short on good old-fashioned gossip about Hollywood personalities, but it also provides real insight into the tricky business of reshaping movies in the cutting room.

Some of my favorite stories involve a 1979 debacle called Hurricane, produced by the outrageous Dino De Laurentiis. Here’s IMDB’s capsule description: “The desperate love affair between a young Samoan chief and an American painter, against the will of her father. Amid this man-made tension comes a hurricane so devastating, the lives of the lovers and the entire island are imperiled.” De Laurentiis insisted that this pulpy saga be shot in beautiful but remote Bora Bora, which at the time had no telephone service and no natural resources beyond fish and tropical fruit. Everything had to be shipped in from L.A.: sets, thousands of yards of fabric for costumes, and so on. De Laurentiis built a hotel to house cast and crew, then flew in two of Italy’s best chefs, along with enough food and drink to feed an army. Naturally, everyone went stir-crazy. O’Steen, not one to mince words, bluntly describes star Mia Farrow “eye-fucking” (and more) both director Jan Troell and cinematographer Sven Nykvist. And co-star Timothy Hutton, who turned paranoid during the shoot, is still infamous for the day he peed on De Laurentiis’s spiffy Italian loafers.

More Sam O’Steen to come! .

Published on September 08, 2015 14:22

September 4, 2015

Irwin Keyes, Eric Caidin, and Some Others: How to Make a Showbiz Life

The late Irwin Keyes, as captured by the Coen brothers

The late Irwin Keyes, as captured by the Coen brothersAs Labor Day Weekend approaches, I find myself marveling at the number of ways people maintain connections to the film industry. Usually we think of Hollywood in terms of wealth and power. Most entertainment attorneys are looking to segue into becoming producers. And most actors fancy themselves as up-and-coming stars.

But today I want to salute the grunts of the industry, the folks who play the supporting roles, whether on or off camera. I tip my hat, first of all, a guy who – when not on the set -- hung out at my local Starbucks. Irwin Keyes was known to collectors of showbiz trivia as a fixture in sitcoms (like The Jeffersons) and horror films. In the latter, he was helped by his oddly distorted facial features, a result of acromegaly, the pituitary disorder that killed him two months ago, at the age of 63. Anyone who’s seen Irwin play a hitman named Wheezy Joe in the Coen brothers’ Intolerable Cruelty will not soon forget him. If you’ve watched the film, you know it’s definitely not a good idea to confuse your gun with your asthma inhaler. Irwin Keyes, hail and farewell.

Irwin was never a star, but at least he appeared on screen. Countless others are essential figures on the set, but never get to wear a costume and play a role. I’m talking about (for instance) those who train and oversee animal actors. In the words of the industry, they’re “wranglers.” They may be dealing with cats, dogs, livestock, or more exotic critters. In one Concorde film, The Nest, we had an official bug wrangler, who kept watch over our stock of killer cockroaches. Another kind of wrangler, I guess, is the certified teacher charged with making sure that child actors don’t neglect their schooling or otherwise get into trouble.

One friend of mine, Diana Caldwell, comes from a family of actors. She aspired to be a screenwriter, but needed an actual paying gig. That’s why, just out of college, she chose to put her skills as a projectionist to work. Fortunately, she gained entrée into a male-dominated profession when a leader of the local union, one who enjoyed thumbing his nose at the Establishment, decided to take her on. Over the years, she’s learned to adapt to changing equipment, while vastly improving her skills. For years she’s worked for Boston Light and Sound, whose head, Chapin Cutler, is famed for his work as a film preservationist. She also plies her trade at major film festivals where anything can happen in the projection booth – and usually does.

Then there are lifelong film fans who turn their enthusiasm into business ventures. An L.A. Times piece recently featured John Wyatt: for the last decade he’s run the hyper-popular Cinespia series of classic film screenings on the lawn of the historic Hollywood Forever Cemetery. On nearby Hollywood Blvd., Jeff Mantor owns and operates the venerable Larry Edmunds Bookshop, which has served cinema buffs for eight decades. It used to be that foreign travelers, making a pilgrimage to Hollywood, would buy an extra suitcase to take home movie books, movie posters, lobby cards, and stills. Today’s airline regulations make that more unlikely, and – despite the loyal patronage of filmmakers like Joe Dante and John Landis -- the fact that the store is today the only one of its kind in Hollywood cuts down on its attraction for daytrippers. Just last May, Eric Caidin of the neighboring Hollywood Book and Poster died suddenly while attending a film noirconvention in Palm Springs. Here’s to Eric and to Jeff, the last of his breed.

Published on September 04, 2015 10:59

September 1, 2015

Keeping Abreast of Horror (in movies and in life)

My favorite schlockmeister, Jim Wynorski, once told Time magazine that “breasts are the cheapest special effects in the business.” Jim should certainly know. As the director of such latter-day Roger Corman classics as Sorority House Massacre II as well as his own cheapie exploitation fare (like The Bare Wench Project and The Devil Wears Nada), he has staked his career on nubile young women who’ll come onto the set willing to pop their tops.

But it’s not just Jim. All of Hollywood sometimes seems to be hung up on breasts, to the amusement of the European filmmakers who have long been much more relaxed about the human body. François Truffaut made a graphic visual joke about this contrast in his 1960 New Wave classic, Shoot the Piano Player. In America, the on-screen unveiling of breasts actually changed the course of the movie industry. Back in 1964, Sidney Lumet used the powerful intercutting of two topless moments to highlight the Nazi degradation of body and spirit in The Pawnbroker. Lumet’s obvious seriousness of purpose led his film to receive – after much pondering -- the coveted MPAA seal of approval, and this landmark event ultimately spelled the death knell for the old Production Code.

Today, of course, seeing a woman’s bare breasts on-screen is about as common in a big studio release as in a Roger Corman quickie. On the red carpet, the flaunting of mammaries is very much part of the excitement. No one arrives topless, to be sure, but the peekaboo look is almost obligatory, and not just for MTV types. Such well-toned Hollywood royalty as Angelina Jolie seems to take pride in strategic body-baring. Which made it all the more of a shock when it was announced in early 2013 that Jolie had undergone a preventive double mastectomy in order to lessen her chances of contracting breast cancer.

Jolie chose to be open about her situation in the press, as a way of encouraging other women to make informed choices. One who has benefited directly from her candor is young journalist and author Lizzie Stark. Stark’s powerful 2014 memoir is titled Pandora’s DNA: Tracing the Breast Cancer Genes Through History, Science, and One Family Tree. Like Jolie, Stark is the bearer of a mutation on the BRCA1 gene that almost guarantees breast cancer. Nearly every female member of her family has been afflicted, many at young ages. That’s why Stark, a newlywed still in her twenties, decided to go under the knife herself.

Stark, a gifted writer, confronts the situation in lively, unintimidating prose. Here’s her discussion of various types of cancer: “Some are ninjas—nimble, lethal, and hard to kill—while others blunder around like drunken frat boys—clumsy and slow-moving, but still capable of pushing you down a flight of stairs if you don’t watch it.” She spells out the science of the BRCA mutation, and gives some details about the history of the mastectomy that should make woman glad to be living in a slightly more enlightened age. But the heart of the book is the frank examination of her own psyche as she moves through this whole disfiguring process. One aspect I didn’t expect: in a chapter called “Ta-Ta to Tatas,” she reveals both her ambiguous attitude toward her own post-reconstruction breasts and the way her whole physical self-presentation (hair, makeup, clothing choices) has dramatically changed as she absorbs the new normal. This is not an easy book to read, but I applaud Lizzie Stark for making the best of a really bad situation and moving onward with courage and grace.

Farewells are in order for two male cancer victims. One is neurologist Oliver Sacks, whose writings about the quirks of the brain led to such Hollywood projects as the film “Awakenings.” The other, of course, is Wes Craven, who made films about horrific invaders, then faced the ultimate one himself.

Published on September 01, 2015 14:21

August 28, 2015

A Live Interview Turns Deadly: Seeking Stardom in Roanoke

We’ve all heard by now about the bloody doings in Roanoke, Virginia: of how a disgruntled ex-reporter at WBDJ-TV shot and killed two of his former colleagues while they were in the midst of an on-air interview. My first thought, other than profound sympathy for the victims and their loved ones, was that this sounded like one more reminder that Paddy Chayefsky’s Network – which predicts on-air death as a ratings draw – is alive and well.

But my thinking evolved as I learned more about the behavior of Vester Lee Flanagan II, who went by the professional name of Bryce Williams. This was a man who was determined to be noticed. Not only did he fax to ABC News a lengthy diatribe spelling out his grievances but he also managed to videotape the actual shootings, then posted them on Facebook and Twitter, where they were seen by thousands before the accounts were taken down.

All of which reminds me of a book published by biographer and film historian Neal Gabler back in 1998. Gabler’s Life: The Movie begins by focusing on a movement he calls the Entertainment Revolution. Says Gabler, “the desire for entertainment—as an instinct, as a rebellion, as a form of empowerment, as a way of filling increased leisure time or simply as a means of enjoying pure pleasure—was already so insatiable in the nineteenth century that Americans rapidly began devising new methods to satisfy it.” If nineteenth-century Americans craved entertainment, how much more did it appeal to their mid-twentieth-century descendants, who could flick on their radios and television sets whenever they took the notion. And one of the century’s most popular political figures, Ronald Reagan, succeeded with the public because – as a professional movie actor – he knew just how to tap in to America’s love of stories with good-guy heroes and happy endings.

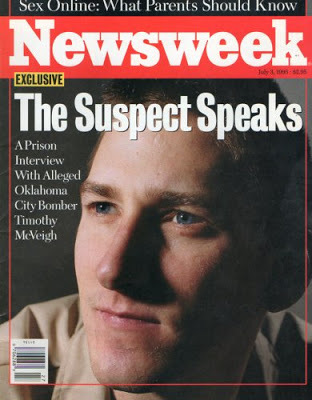

Though Reagan’s appeal was that of a man in a white hat, some seriously flawed human beings have also sought public attention as the leading actors in big public dramas. And, to a certain extent at least, the mass media have helped them make their case. Gabler points out that Timothy McVeigh, later to be convicted for the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, was actively courted by news sources to tell his story. The result was a soulful photo on the cover of Newsweek; he also negotiated for the right to choose among such celebrity interviewers as Barbara Walters, Diane Sawyer, Dan Rather, and Tom Brokaw, with the program to be aired during a ratings-sweeps week.

Gabler informs us that “John Lennon’s assassin, Mark David Chapman, had left a tableau in his hotel room—a photo of Judy Garland with the Cowardly Lion, a Bible inscribed to Holden Caulfield (the protagonist of J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye), a photo of himself with refugee children—that he thought would suggest a motive behind his crime. In short, he was providing a theme as well as an act.” And we learn that Arthur Bremer, who in 1972 would shoot and paralyze presidential candidate George Wallace, explicitly viewed himself as an actor in a film, “so much so that while stalking President Nixon, his initial target, he missed the chance to kill him when he raced back to his hotel to change into a black suit.”

Social media, of course, makes it all the easier to become an overnight celebrity. Now Vester Flanagan is just that. But of course he’s dead . . . and so are two journalists who were unlucky enough to cross his path.

Published on August 28, 2015 12:30

August 25, 2015

Beverly in Movieland Visits Sesame Street

It’s far from a sunny day on Sesame Street. The show is decamping from PBS, its home for almost five decades, to pricier digs at HBO. And Maria, played for the past 44 years by Sonia Manzano, is retiring from the Fix-It Shop to take up residence in a year-round sunny clime, like maybe Miami Beach or San Juan.

I can’t pretend that I grew up on Sesame Street. My own black-&-white TV childhood was spent with bland characters like Howdy Doody, Sheriff John, and the matronly Miss Francis of (ugh!) Ding Dong School. Sesame Street, when it popped up in 1969, had plenty of innovations that I came to appreciate later, as a mother of young children. First of all, it used the medium of television in a way that earlier shows did not. Jim Henson, who was there from the start, contributed not only the Muppets but also the brilliantly-colored and visually inspired graphics that marked the show. There was also a creative sense of inclusiveness: Sesame Street, with its very Sixties awareness of racial inequities, created a rainbow brigade of characters, a far cry from the exclusively WASP cast of The Mickey Mouse Club. Not only were the majority of the regular human characters black (Gordon and Susan) and Latino (Maria and Luis), but the presence of orange, yellow, and blue Muppets suggested that warm, cuddly individuals exist in our world in all colors, shapes, and sizes. And Sesame Street, which was particularly planned to capture the imagination of inner-city kids, was not afraid to have an urban look. Previously, children’s programming seemed always to be set in some Dick-and-Jane-style dream-suburbia, like Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. On Sesame Street, by contrast, there were stoops, and alleys, and trashcans (but no trash).

Sesame Street also seemed willing to talk about real life-and-death issues, though in the gentlest way possible. Human characters fell in love, got married, had babies. Perhaps the show’s most famous foray into reality came after Will Lee, the actor who’d played crusty but lovable Mr. Hooper since the show’s beginning, died suddenly in 1982 at the age of 74. The decision to incorporate the death of a beloved Sesame Street personality into the show, from the perspective of oversized five-year-old Big Bird, was not easily made. But the “Goodbye, Mr. Hooper” episode – which also captured the cast’s genuine grief at the loss of a longtime friend -- was to become one of the show’s most honored of all time. (I confess I can’t watch it without tearing up a little. Like everyone else in my age group, I’ve lost so many good people over the years.)

If Sesame Street could be sad, it was also very funny. The show’s creators had the foresight to understand that children would learn far more if their parents watched too. And parents, of course, would expect to be entertained on their own level. Which is why the show has always made a point of riffing on popular culture, often with the cooperation of major showbiz figures. In the heyday of the Beatles, I always chuckled at the salute to the letter B, set to the tune of “Let It Be.” And I particularly liked the Monsterpiece Theatre segments, parodying such landmark PBS dramatic series as Upstairs Downstairs. These were presented by Cookie Monster in the guise of the suave, smoking-jacketed Alistair Cookie.

Suffice it to say that the influence of Sesame Street lives on. Some of its fans even grew up to create Avenue Q, a Broadway hit that probes what’s really going on between Bert and Ernie.

Published on August 25, 2015 15:48

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers