Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 108

July 17, 2015

Atticus Finch and Mr. Hyde: Questions Posed by “Go Set a Watchman”

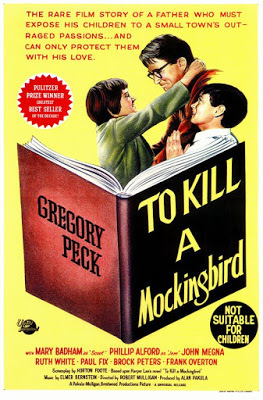

No, I don’t plan to read Go Set a Watchman, the just-published novel by the author of the much-revered To Kill a Mockingbird. I must say, though, that the brouhaha surrounding Harper Lee’s new book fascinates me. It was written in the 1950s: most reviewers see it as an early version of To Kill a Mockingbird, submitted to a major New York publisher that bought it on condition of an intensive page-one rewrite. In the course of which, Lee apparently decided (or was persuaded) to flesh out her adult heroine’s childhood memory and build the entire novel around it. At least one critic, though, finds this backstory unconvincing, and insists that Go Set a Watchman was Lee’s attempt at a sequel to her famous tale of little Scout Finch and her father Atticus, the small-town Southern lawyer who courageously defends a black man charged with raping a white woman.

Harper Lee is still alive, though there've been reports she's in no condition to comment on the unearthing of this early work. By now, I've heard the pro and the con on this matter, but I'm leaning toward believing she's endorsed the publication. From what I gather, though, this is not a novel that’s going to burnish her legacy.

Go Set a Watchman, which focuses on the mature Scout returning to her hometown from New York City, will mostly be remembered for blackening the image of her beloved Atticus. It’s nothing unusual, certainly, for young adults returning home to suddenly see their parents in a new light. Once you’ve spent time out in the world, your father and mother appear far more fallible than they did when you were growing up. But—from all reports—Atticus in Go Set a Watchman seems not just flawed but a different person entirely from the one we thought we knew in both the novel of To Kill a Mockingbird and the revered screen version that won Gregory Peck his Oscar. There he was reasonable, open-hearted, and wise: all the things you’d wish for in a father figure. In this new book, he’s a staunch segregationist, an unreconstructed bigot, even a white supremacist. Personally, I don’t want to see my mental image of Atticus Finch destroyed—and Go Set a Watchman apparently doesn’t have much to offer us in place of that once-heroic figure.

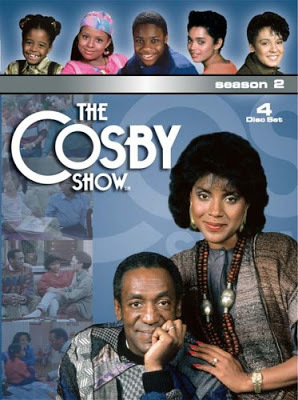

Curiously, the whole situation reminds me of the Bill Cosby fiasco: the fact that we feel shattered by the knowledge of a man who doesn’t live up to his well-loved TV image. Cosby’s misdeeds, terrible though they are, wouldn’t be quite so disturbing if he were known for playing bad guys. The truth is that we all have a hard time separating the role from the actor. That’s why it was so jarring when Tom Cruise, with his boyish smile and long list of good-guy roles, turned out to be a religious wacko. Or when the equally appealing Mel Gibson revealed his nasty side. For many movie fans, John Wayne was a hero because he played heroes, even though he never got anywhere near an actual battlefield. And I’m certain that Ronald Reagan would never have been elected president if he’d made a career out of villain roles.

Isn’t a Harper Lee sequel to To Kill a Mockingbird worth reading, just to find out what happens next? Well, maybe. But there’s the sad example of Charles Webb’s 2008 sequel to his famous 1962 novel, The Graduate. What happens when Ben and Elaine get off of that bus? In the words of a smart lady I recently met, “Some things you don’t want an answer to.”

Published on July 17, 2015 09:45

July 14, 2015

El Chapo Escapes to Pluto (or somewhere else in the universe)

Today a NASA spacecraft dubbed New Horizons is scheduled for an historic flyby of Pluto. And today’s big headlines feature the notorious drug lord, Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, who escaped from an high-security Mexican prison by way of an air-conditioned tunnel leading out of the shower stall in his cell. New Horizons? Escape from prison? The time seems ripe for me to salute my stint at Roger Corman’s film companies—like New World Pictures and Concorde-New Horizons—where prison-escape movies were once a way of life.

To be honest, when I think of Corman prison movies, my mind mostly goes back to the New World Pictures era (1970-1983), when we launched such lucrative and thoroughly exploitative films as The Big Doll House, The Big Bird Cage, and (inevitably) The Big Bust Out. These and similar features were shot in the Philippines with a hardy and voluptuous cast that generally included Roberta Collins and the bodacious Pam Grier. Among enthusiasts, the “babes behind bars” movies have been hailed as feminist in nature. Yes, the young women are brutally subjugated for several reels, often by a nasty warden and a prison matron with distinct bulldyke proclivities. But they are far too feisty to take the outrages against them lying down. Launching a cunning plan to escape, they spend the rest of the film turning the tables on their oppressors. Still, this is feminism of a rather specialized sort. Onetime Corman assistant Laurette Hayden once joked with me about how the female lead is inevitably falling out of her clothing while running through the jungle: “I think the faster she runs, with the machete in her hand, the more quickly the clothes fall away.”

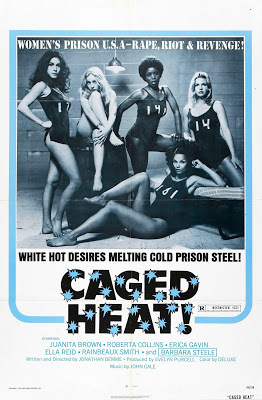

Another Corman “women in prison” movie, Caged Heat (1974), made cinema history of sorts because it was the first film directed by Jonathan Demme, who would go on to win the Best Director Oscar for Silence of the Lambs. The eighty-four-minute Caged Heat, starring Roberta Collins and Barbara Steele (as, of course, the steely matron), was shot locally on a $180,000 budget. The marketing campaign was typically lurid—the ads screamed “White hot desires melting cold prison steel!”—but Demme’s film actually earned some respectful press. The Los Angeles Times’ Kevin Thomas, one of several critics nationwide who would admit to enjoying New World product, described Caged Heat as having “wit, style, and unflagging verve.… [It] sends up the genre while still giving the mindless action fan his money’s worth.”

The assumptions behind these outlandish movies are worth examining. First of all, virtually everyone languishing behind the bars of these prisons is fundamentally innocent; it’s the sadistic guards who are the real criminals. Sexuality is a weapon that cuts both ways: our heroines use their female allure to taunt and trick their captors, but the horny prison staff, lusting after their juicy captives, force sex as a blunt form of punishment. Fortunately for the leading ladies, their captors aren’t too bright. Once our gals overcome their interpersonal differences and decide to work together, there’s nothing they can’t accomplish, including busting out of a maximum-security clink.

When I headed the story department at Concorde-New Horizons, deposed Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega escaped from captivity. Roger was thrilled by this opportunity to make a “ripped from the headlines” suspense drama, The Hunt for Noriega. He hired a screenwriter, who was told to crank out a first draft over the weekend. Alas, for our artistic intentions, Noriega was quickly caught.

Somehow, I don’t think finding El Chapo will be quite so simple. But maybe Pluto’s a good place to start looking.

Published on July 14, 2015 12:16

July 10, 2015

Bill Cosby, We Hardly Knew Ye

We thought we knew Bill Cosby. He was smart, charming, a thoroughly admirable family man. His very existence gave the lie to bigots who proclaimed their low opinion of African-Americans. Which is one reason why the revelation this week of Cosby’s long-term pattern of sexual misconduct is so very daunting.

Back in the early sixties, when Cosby first appeared on the Tonight Show, my parents breathed a sigh of relief. As the Civil Rights movement ramped up, here was a young black man who didn’t seem marked by anger. Raw humor hinging on questions of race was not for him. He was not, for instance, Dick Gregory. Instead Cosby was funny in a softer way, talking about childhood and other experiences we deem universal.

In 1965, when Cosby was cast opposite Robert Culp in the light-hearted adventure series I Spy¸ he became the first African-American to win a starring role on a network TV series. A few Southern stations declined to show the program, but the rest of us rejoiced that finally a black man could get laughs playing something other than a manservant or underling. The role led to three consecutive Emmys for outstanding lead actor, and a lot of us cheered for this well-deserved recognition.

Then in 1984 came The Cosby Show, a wholesome sitcom that dared to buck stereotypes by presenting a black family that was affluent, educated, and intact. As Dr. Cliff Huxtable, Cosby interacted with his wife and five rambunctious but good-hearted children, dishing out life lessons with an amiable twinkle. For eight years, The Cosby Show was at the top of the ratings chart. A whole generation – white as well as black – grew up imagining Dr. Huxtable as the dad they wished they had.

This well-worn image makes it all the more shocking that Cosby -- who in recent years has taken to lecturing younger African-Americans about good behavior -- has now been revealed as a man with a taste for giving young women Quaaludes as a prelude to sex. The rumors had been flying for years, but Cosby’s own responses as contained in newly unsealed ten-year-old court documents seem to remove all doubt.

Is Dr. Cliff Huxtable a rapist? All signs point to yes. I’m tremendously disheartened by that possibility, especially after hearing the accounts of some of his accusers. And I’m angry too. Not simply that he’s managed to avoid prosecution for so long but also because others have aided and abetted him, simply because he’s a star. The ten-year-old deposition mentions Tom Illus of the William Morris Agency, who was Cosby’s long-time agent. One of his little tasks, apparently, was to pay off a Cosby victim, no questions asked.

Illus has been dead for four years, so he obviously can’t be questioned further. But his involvement in this ugly situation points to one of the built-in duties of a Hollywood talent agent, to back up your client, no matter what. I have a friend who worked for years for the infamous Sue Mengers. Part of her job was to conceal the whereabouts of a major star whenever he had a fallling-out with his wife.

This past week saw the death of Jerry Weintraub, an agent who went on to becomr one of Hollywood’s great producers, responsible for Nashville, Oh God!, and The Karate Kid. It’s classic to start in the mailroom of a talent agency, qualify as an actor’s representative, then gradually remake yourself as a producer. An agent can do wonderful things, as Weintraub did. But he or she can also be called on to conceal terrible ones.

Published on July 10, 2015 10:24

July 7, 2015

German Film Today: Hollywood Uber Alles

IMAX Theater, Potsdamer Platz

IMAX Theater, Potsdamer PlatzThe American premiere of Terminator Genisys was something of a bust over the Fourth of July weekend. But perhaps there’ll be more fireworks when the movie opens in major German cities on July 9.

I’m just back from a business-and-pleasure trip to Deutschland. Once upon a time, my knowledge of Germany came from movies, everything from 1961’s grim Town Without Pity (filmed in bleak black-and-white in the charming Bavarian town of Bamberg) to 1972’s diabolically gaudy Cabaret. And then of course there were all those World War II epics. Many were not filmed on German soil. But Stanley Kramer made sure that his powerful 1961 Judgment at Nuremberg, which addresses the question of justice in the post-Nazi era, included footage of the city in which the famous war-crimes trials actually took place.

Germans love movies. And Germany has contributed hugely to the history of world cinema. The post-WWI movement known as German Expressionism, which spawned such stylistically bold films as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, helped revolutionize movie aesthetics. It’s tremendously sad that brilliant artists like Fritz Lang (whose Metropolis and M continue to influence the science fiction and horror genres) were chased out of Germany during the Nazi era, condemned as being “degenerate.” Of course, Germany’s loss was Hollywood’s gain. Lang and other Austrian and German filmmakers, many of them Jewish, found the welcome mat out for them in Beverly Hills. Some fared better than others, but screenwriter Billy Wilder, for one, soon became a master of filmmaking Hollywood-style. Some Like It Hot, anyone?

In the era when Roger Corman distributed major art films, I was well aware that the German motion picture industry was staging a comeback. Such artists as Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Volker Schlöndorff, and Werner Herzog were making names for themselves with uniquely German films like Aguirre, The Wrath of God and The Tin Drum. I also knew about the rise of domestic German product, innocuous dramas and sex comedies as shlock-filled as anything low-budget Hollywood could muster.

Which brings us to today. Everywhere I went in Germany, I saw notices for film clubs and film museums. (In Frankfurt, Ben & Jerry’s – yes, the Vermont ice cream chain – hosts regular free movie nights, with American flicks like Crazy Stupid Loveon the roster.) American TV is hardly excluded: you couldn’t miss all the German-language posters for the next season of Masters of Sex and especially Orange is the New Black.

Though Munich has a vibrant film industry, the center of cinematic activity is clearly Berlin. Berlin’s glitzy Potsdamer Platz, transformed from the days when it was a drab GDR outpost, now rivals Times Square with its neon-lit movie palaces. In the glass-enclosed Sony Centre, the Museum Für Film und Fernsehen (that’s film and TV) hosts exhibits I wish I’d had a chance to study. One star of the collection is Marlene Dietrich, the German-born singer and actress who decisively turned her back on her home country during the Nazi era. There’s a café named for Billy Wilder too. And across the street from the Sony Centre you can buy advance tickets for Arnold Schwarzenegger’s latest Terminator incarnation. This is the locale where the prestigious Berlin Film Festival (aka the Berlinale) annually hands out its Golden Bear awards

But other parts of Germany get into the act in their own way. I’m told George Clooney’s Monuments Men was filmed at Neuschwanstein Castle and elsewhere in Deutschland. And it was the delightful walled medieval city of Nördlingen you saw from the top of the great glass elevator at the end of Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory.

Nordlingen: Willie Wonka's eye view

Nordlingen: Willie Wonka's eye view

Published on July 07, 2015 12:31

July 3, 2015

Plane and Fancy: Looking for Happy Landings

When movies were young, back in the 1890s, there was something called the Kinetoscope. This device allowed one viewer at a time to watch a very short film—on the order of “Fred Ott’s Sneeze”—through a peephole. Kinetoscopes were featured at amusement arcades, but it was not long before the concept of the movie theatre developed. From that time onward, movies were screened for mass audiences, and the communal experience became part of the allure.

Times, of course, have changed. We can now watch movies at home on our television sets or computer screens. We can even, if we’re obsessive, view them on our smartphones. But it was on a series of long airplane rides that I really came to feel I was returning to the peepshow days of old. On my recent Lufthansa flights to and from Frankfurt, every seat in economy class was equipped with its own small screen. Wearing a set of headphones and navigating via a touchscreen, I had free access to what seemed like hundreds of movies. I learned I could relieve the tedium of air travel by way of an up-close-and-personal moviegoing orgy, but also that certain types of flicks work much better than others when you are folded into a cramped seat for over ten hours of flying time.

On my outward-bound flight, I chose carefully, and ended with a satisfactory playlist. This was my chance to catch up with Wes Anderson’s The Darjeeling Limited, in which three oddball siblings played by Owen Wilson, Jason Schwartzman, and Adrien Brody travel by train across India as a way of coming to terms with their father’s death. To continue with the Indian motif, I moved on to The Second Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. This was far more light-hearted than the Anderson film, and tried (overly?) hard for the exuberance of Bollywood extravaganzas. Still, the two flicks were similar in focusing on a westerner’s bedazed response to the chaotic splendors of India. After all that exoticism, it seemed fitting to return to the tried-and-true charms of a European fairytale. Kenneth Branagh’s Cinderella had both magic and gusto, thanks to the nastiness of Cate Blanchett’s wicked stepmother. But for me the big surprise was Ex Machina, a scifi thriller with both a sleek look and a twisty storyline. Ex Machina is hardly a cast-of-thousands epic, and the very simplicity of its dramatic demands made it ideal airplane viewing.

Coming home, I did less well. Tim Burton’s Big Eyes, the story of Margaret and Walter Keane, was easy enough to follow, but the characters played by Amy Adams and Christoph Waltz never entirely held my interest. I next checked out Les Miserables, to see how well a solemn and grandiose stage musical could transfer to the screen. Alas, the combination of realistic squalor and characters belting arias into the camera lens struck me as grotesque, and I quit well before the midway point. Another film that didn’t work was Kingsman, the British spy caper that seemed much too complicated to follow, given the distractions of meal service and seatmates jostling to reach the aisle.

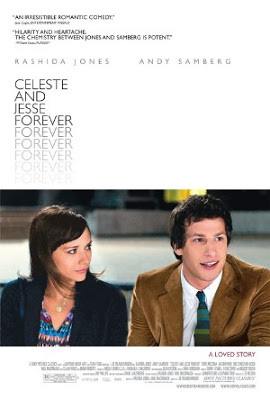

Finally I settled on an intriguing little romantic flick I’d barely heard of: Celeste and Jesse Forever. Its producer, co-writer, and star is Rashida Jones, the talented and gorgeous daughter of Quincy Jones and TheMod Squad’s Peggy Lipton. She plays opposite Andy Samberg, but in this rueful contemporary tale these two soulmates are not moving toward marriage, but rather toward divorce. It’s well-played and seems wholly contemporary. Today I guess no one seems to expect happily-ever-after.

Published on July 03, 2015 10:08

June 30, 2015

The Graduate’s Elizabeth Wilson: And Here’s to You, Mrs. Braddock

Elizabeth Wilson: it’s not a name with a Hollywood ring to it. And in fact most of Wilson’s triumphs were on Broadway, in a wide range of classical and contemporary plays. But Wilson, who died this past May at the age of 94, had indelible supporting roles in several hit films. In Nine to Five, she played the office snitch. She was Charles Van Doren’s mother in Quiz Show and (near the end of her life) Franklin D. Roosevelt’s mother in Hyde Park on Hudson. Yet for me her most unforgettable gig was portraying the mother of Benjamin Braddock in The Graduate.

Most fans of The Graduate probably don’t remember Mrs. Braddock. I suspect they’re too busy focusing on the film’s other women: the slinky and dangerous Mrs. Robinson and her beautiful, virginal daughter, Elaine. But it’s worth paying attention to the dynamic in Ben’s home, where his affable parents shower him with presents, but in return expect him to entertain their guests with his collegiate accomplishments. (“You’re disappointing them, Ben,” scolds his father, when our hero shows reluctance to demonstrate in the family swimming pool the virtues of his new SCUBA gear.) Ben’s dad habitually plays the ringmaster in this family circus, with his wife cheering from the sidelines. Tall and well-coiffed, dressed in stylish but slightly wacky leisurewear, she seems to thoroughly enjoy her husband’s monkeyshines. Whether barbecuing burgers for the backyard guests, scrambling eggs for her family, arranging roses in a vase, or fussing with Ben’s collar as he descends to greet his parents’ partygoing friends, she is the perfect (and perfectly charming) Beverly Hills matron.

Which should not imply that she’s in any way bland. This woman has spunk. There’s a scene in which parents and son are all floating in that swimming pool. The Braddocks simply can’t understand why Ben is so loathe to take out the Robinsons’ pretty daughter. Mrs. Braddock (decked out in the kind of frilly plastic bathing cap I remember all too well from my childhood) cheerfully forces the issue by announcing that if Ben won’t cooperate, she’ll simply have to invite all the Robinsons to dinner. Since Ben is secretly sleeping with his father’s partner’s wife, this is one scenario he can’t endure. Result: in the very next scene, Ben shows up at the Robinson home to claim a date with Elaine.

If Mrs. Robinson has been manipulating young Ben from the start, Mrs. Braddock is in her way equally adept at bending him to her wishes. That’s, in a sense, what moms do. (I mean no disrespect: I’ve personally been on both sides of the mother/child equation.) But there’s a huge difference between the two women. Whereas Mrs. Robinson acts out of discontent, hating her husband, her marriage, and everything about her comfortable but empty life, Mrs. Braddock is motivated by affection. She and her husband are a successful team. (At times we might even call them co-conspirators.) She loves her son too, and wants only the best for him. The only problem is that she and her husband are a tad too insistent on shaping his future in their own image.

I’ve seen a costumer’s snapshots for The Graduate, showing both Anne Bancroft’s Mrs. Robinson and Elizabeth Wilson’s Mrs. Braddock in their wardrobes for the film. Bancroft is clearly having a ball, vamping for the camera. Wilson, though, looks a bit abashed, her eyes averted. She’s an actress, not a fashion-plate, and in Mrs. Braddock’s glitzy outfits her modest demeanor gives a hint of the woman behind the character. Here’s to you, Elizabeth Wilson! Hail and farewell.

Published on June 30, 2015 10:00

June 26, 2015

Staying in the Picture with Robert Evans

In Hollywood, it never hurts to have a gift of the gab. Robert Evans, who’s certainly had his share of showbiz ups and downs, started out as a handsome young actor, detoured into a stint in women’s pants (his brother was a founder of Evan-Picone), ran Paramount Pictures during its glory days, got into serious legal hot water, got canned, then eventually wrote a memoir that got better reviews than any of his films, including The Godfather and Chinatown. Evans’ book is called The Kid Stays in the Picture , in tribute to Darryl F. Zanuck, who insisted that Evans not be booted from the unlikely role of a Spanish bullfighter in the film adaptation of Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises (1957). So successful was The Kid Stays in the Picture, which came out in 1994, that it eventually was made into a 2012 documentary that was a hit at Cannes.

Evans’ book has clearly not been massaged by a ghost writer and then vetted by a conscientious publicist. He explains his modus operandi right off the bat (these quotes are taken from the intro to the 2013 edition): “To tell the truth . . . and nothin’ but the truth . . . yet stick a bit of lightnin’ up the reader’s ass—that’s one mean hat trick. Don’t care how talented you are, or think you are. If you meant to make truth jump from the page, you need a hook!” Talk about finding your voice as a writer! He goes on to say, directly contradicting the values of ardent grammar cops like me, “Forget grammatical perfection. Leave that to the pens of the more talented. Who the fuck wants to go toe-to-toe with George Bernard Shaw, anyway? Shock ‘em with the unexpected! . . . Let ‘em laugh at you. But be you. Be an original!”

And here’s the book’s much-quoted epigraph: “There are three sides to every story: yours . . . mine . . . and the truth. No one is lying. Memories shared serve each differently.”

Much later in the book, Evans pauses to sum up his highly original life, which has included pursuing Grace Kelly, tangoing with Ava Gardner, feuding with Frances Ford Coppola, plucking Jack Nicholson out of the Roger Corman ghetto, and marrying Ali MacGraw. Not to mention staging a impromptu Passover seder intended to convince Roman Polanski to direct Chinatown: guests included Walter Matthau, Sue Mengers, Warren Beatty, and Kirk Douglas, who presided in perfect Hebrew. Here’s his take on two key decades in his life: “As the fifties aged, so did I. Made it to the big screen! Beaten up by Errol Flynn, kissed by Ava Gardner, slapped by Joan Crawford, toe-to-toe in close-ups with Jimmy Cagney. Not bad, huh? Not good either. By decade’s end, I was sure of one thing: I was a half-assed actor.”

“The sixties? That’s a different story. No back door this time – front door all the way. ‘Run the joint,’ was the order of the decade. Run it I did, for more than a decade. First and only actor ever to make the jump. Don’t understand it. This world of fickle flicks? It’s been well over thirty years now and I’m still here, still standing behind them same gates. Bet your house, it isn’t dull. I’ve either done it, or gotten it. You name ‘em, I’ve met ‘em—well, almost. Either worked with ‘em, fought with ‘em, hired ‘em, laughed with ‘em, cried with ‘em, been figuratively fucked by ‘em, or literally fucked ‘em. It’s been one helluva ride!”

And one helluva read.

Published on June 26, 2015 10:00

June 23, 2015

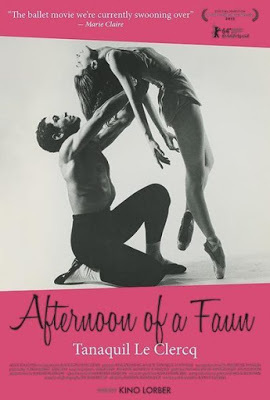

Afternoon (and Evening) of a Faun: Tanaquil Le Clercq

Ballet is so often about heartbreak. In Swan Lake, after her lover proves unfaithful, Odette is trapped in the body of a swan. Giselle goes mad and dances herself to death. And so on and so forth. And then there’s the story of Tanaquil Le Clercq. This real-life saga is so poignant that it inspired a documentary film: Afternoon of a Faun.

The documentary’s title points back to a short, intimate duet (set to the music of Debussy) choreographed by Jerome Robbins on behalf of his sometimes-dance partner at the New York City Ballet, Tanaquil Le Clercq. About that exotic name: Amanda Vaill, Robbins’ stellar biographer, explains that Tanny was “born in Paris to an American mother and French father and named after an Etruscan queen of the fourth century BC.” Jerry Robbins was short and streetwise; Tanny was unusually tall, long-limbed, and elegant. (Her frequent partner Jacques d’Amboise later described her as “this elongated, stretched-out path to heaven.”) Though physically very different, Robbins and Le Clercq shared intelligence and a wicked sense of humor. Their emotional connection lasted throughout their lives. In his final years, Jerry placed at his bedside a framed photograph he’d taken of Tanny, so that he could gaze at it first thing in the morning and last thing at night.

Though Robbins and Le Clercq adored one another, his bisexuality certainly complicated their relationship. Then, at age 23, she fell under the spell of George Balanchine, co-founder and artistic director of the New York City Ballet. Balanchine, himself a great choreographer, was in the habit of falling for the ballerinas who inspired him. At 48, he had already wed and shed four, including Vera Zorina and Maria Tallchief, when Tanny came into his line of vision. They were married at midnight as the year 1953 began. A letter spelled out the situation to Jerry: “I just love you, to talk to, to go around with, play games, laugh like hell, etc. However I’m in love with George. Maybe it’s a case of, he got here first.”

Then came the year 1956. While Jerry Robbins was on busy on Broadway, launching The Bells Are Ringing and pondering the project that would become West Side Story, Tanny and the New York City Ballet were touring the capitals of Europe. Suddenly, in Copenhagen, she began to feel flu-ish. The next morning, she found herself paralyzed from the waist down. It was infantile paralysis: Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine was still so new that it was being used mostly on school children, and she had skipped being vaccinated before her European trip. Though Tanny survived days in an iron lung, it was clear she’d never dance (or walk) again. She had just turned 27.

Balanchine remained by her side throughout the crisis, but he was soon emotionally moving on. Inevitably his eye strayed to others, including a new young ballerina, Suzanne Farrell. In 1969, he initiated a quickie Mexican divorce from Tanny in the vain hope of winning Suzanne. As always, Jerry Robbins was her comforter and court jester in this crisis.

Amanda Vaill’s Somewhere ends with the death of Jerome Robbins in 1998, at the age of 79. In 1994, he’d had a poignant dream of Tanny standing and walking. But she was still wheelchair-bound when she passed away in 2000, age 71. According to the documentary, she lived out her last years as a book author and a teacher of dance, inspiring the young students at the school of the Dance Theater of Harlem. I too am inspired by someone who discovered how to begin again.

Here’s a fascinating web tribute to Tanaquil Le Clercq, in the form of a book review of a 2012 novelization of her post-Balanchine life.

Published on June 23, 2015 10:00

June 19, 2015

Jerome Robbins: Leaping from Stage to Screen with West Side Story

We mostly think of Jerome Robbins as a stage creature. There are all those ballets he choreographed for George Balanchine at the New York City Ballet. He supplied the dance numbers for such Broadway gems as On the Town and The King and I, then both directed and choreographed everything from Peter Pan to Gypsy to Fiddler on the Roof.

But he loved movies too. With the help of Amanda Vaill’s marvelously insightful Somewhere: The Life of Jerome Robbins , I want to focus here on the transition from stage to screen of perhaps his most famous production, West Side Story.

Jerry Robbins was part of the West Side Story team from the very beginning. In fact, the original idea came from him. While studying at the Actors Studio, he advised young Montgomery Clift on how to make the part of Romeo relevant to the modern world. The trick, he felt, was to think about the tight-knit ethnic enclaves of New York City: “What would you do if you were an Irish Catholic kid and fell in love with a Jewish girl? . . . And what if you were in a gang, and her people were too, and there was fighting?”

By the time Jerry and colleagues Arthur Laurents, Leonard Bernstein, and Stephen Sondheim were ready to transform this concept into a Broadway musical, the ethnicities of the central characters had changed. At first, potential backers simply weren’t interested. But West Side Story, both directed and choreographed by Robbins, proved to be a stage triumph. And a movie sale quickly followed.

Hollywood was not entirely receptive to Robbins’ talents. He didn’t lack for screen experience, having staged the dance sequences for the film version of The King and I, including the remarkable “Small House of Uncle Thomas.” But the studio honchos who were producing the cinematic West Side Story were determined to hire a veteran Hollywood director. They found one in Robert Wise, who’d helmed successful action films and (years before) edited the great Citizen Kane. Robbins himself was grudgingly hired as co-director, responsible for the musical sequences while Wise concentrated on the book scenes.

Jerry immediately began experimenting with ways to synthesize music, camerawork, and dramatic action, but his extensive notes on every aspect of the project rankled the powers-that-be. As he wrote to a friend back home, “It’s a hard time out here now, and rather than my teaching them how to make the camera dance it’s possible that I’m being taught the limitations of imagination and lack of daring.”

Despite Jerry’s original preference for black-&-white film noir stylistics, the studio bosses insisted on Technicolor and recognizable stars. Natalie Wood was no problem for Jerry: the two got along famously. (Neither had much use for the actor cast opposite her, Richard Beymer.) And Robbins was at his happiest filming a brilliantly danced Prologue on the streets of New York, in a slum area that would soon be cleared to build Lincoln Center. Afterwards, though, while in the midst of staging the Dance at the Gym, he suddenly found himself dismissed. His firing was blamed on the film being over budget, though this was hardly a convincing excuse.

Ultimately, West Side Story collected ten Oscars, with Wise and Robbins sharing the directorial prize (and ignoring one another in their acceptance speeches). Robbins received a special award for choreography as well. Later the film’s screenwriter, Ernest Lehman, paid tribute: “Jerry Robbins is the man behind the gun. He put the bullets in, he cocked it, he shot it—and everybody else is just smoke and noise.”

Published on June 19, 2015 10:00

June 16, 2015

Frank Sinatra: How He Went From Africa to Eternity

I’ve had Frank Sinatra on the brain (and on the stereo) of late. I’ve just finished reading a fascinating 2010 biography by James Kaplan. Called Frank: The Voice , it does a remarkable job of focusing on the man’s evolving singing style. (An upcoming sequel, Sinatra: The Chairman, is due out this fall.) First and foremost, Frank Sinatra was a musical genius. But of course he was many other things too: a husband, a son, a father, an unrepentant philanderer, a power figure, a movie star.

I’m focusing here on a low point in his career. In the early 1950s, life was no longer going his way. His longtime record label dropped him: the bobby-soxers who had once swooned over his romantic ballads were now devoted to Eddie Fisher. Though he’d made big box-office musicals under contract to MGM, Louis B. Mayer was no longer in his corner. He’d traded in a doting wife and family to marry the tempestuous Ava Gardner. With nothing better to do, he’d accompanied her to a movie set in Kenya, where she was to play opposite Clark Gable in Mogambo. On their travels, says Kaplan, “Ava was now the star; Frank, the consort.” It didn’t help that they fought constantly, nor that Ava conceived (and then secretly aborted) his child.

En route to Africa, Sinatra carried with him a battered copy of James Jones’ blockbuster World War II novel, From Here to Eternity. Always a voracious reader, he had fallen in love with the character of Maggio, a cocky buck private from Brooklyn. As Jones describes Maggio, he’s “a tiny curly-headed Italian with narrow bony shoulders jutting from his undershirt.” Both feisty and vulnerable, he can never resist a fight or a crap game. Sinatra reasoned that he was born to play this role. He saw it as his best opportunity to get new respect in Hollywood and to resurrect his fan base. That’s why he bombarded decision-makers like Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures with telegrams begging for the chance to audition.

Finally he took Cohn to lunch and insisted that, though in the past he’d earned $150,000 per film, he’d be willing to take the part for a mere grand a week. But it was not until he landed in Kenya that he was finally invited to test for the role. Since he was flat broke, Ava had to stake him to the cash to fly 13,000 miles to Culver City. There he performed two drunk scenes that encapsulated what Montgomery Clift’s character, Prewitt, says of Maggio: “He’s such a comical little guy and yet somehow he makes me always want to cry while I’m laughin’ at him.”

Others were testing too. The one who seemed to have the inside track was the great character actor Eli Wallach. Many felt Wallach’s test was far superior, but director Fred Zinnemann believed that Wallach’s burly physique was not right for this role. Says Kaplan, “The minute the director saw Sinatra’s small frame and narrow shoulders and haunted eyes, he was intrigued. When Frank condensed all the pain of the last two years into ten minutes of screen test, Zinnemann was floored.”

Kaplan strongly refutes the Hollywood legend that Sinatra, like singer Johnny Fontane in The Godfather, won his dream role because of mob interference. Harry Cohn, a highly practical man, okayed the crooner who was willing to settle for low pay over the expensive Wallach. In return, Sinatra -- helped by his budding friendship with Monty Clift -- turned in a highly disciplined performance. Then came an Oscar, and a new lease on life.

Published on June 16, 2015 10:00

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers