Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 39

January 21, 2022

Fleeing Toward a New World

So you think you’ve got troubles? Thoughts of the Omicron variant getting you down? Well, stop and consider the plight of Amin, who as a young boy fled Afghanistan with his mother and older siblings, after his father disappeared into the clutches of a cruel regime. Paying traffickers for safe passage out of the country, the family ends up in Russia, where they endure in hiding, hassled by cops looking for bribes. As the years pass, their lives become no less harsh. Two sisters barely survive a ghastly trip to Sweden in a shipping container. For the remaining trio, including the aged mother, there’s a forced march involving guides ready and willing to shoot stragglers, followed by a grim winter sea voyage in the hold of a leaky ship. (The bedraggled refugees make it almost to Norway, and are photographed by excited passengers from the deck of a luxury liner, then are promptly sent back to Moscow.)

So you think you’ve got troubles? Thoughts of the Omicron variant getting you down? Well, stop and consider the plight of Amin, who as a young boy fled Afghanistan with his mother and older siblings, after his father disappeared into the clutches of a cruel regime. Paying traffickers for safe passage out of the country, the family ends up in Russia, where they endure in hiding, hassled by cops looking for bribes. As the years pass, their lives become no less harsh. Two sisters barely survive a ghastly trip to Sweden in a shipping container. For the remaining trio, including the aged mother, there’s a forced march involving guides ready and willing to shoot stragglers, followed by a grim winter sea voyage in the hold of a leaky ship. (The bedraggled refugees make it almost to Norway, and are photographed by excited passengers from the deck of a luxury liner, then are promptly sent back to Moscow.)

Amin’s story is told in Flee, an international co-production guided by a writer/director, Jonas Poher Rasmussen, who befriended the actual Amin in Denmark and slowly learned the details he’d hidden within himself for so long. Part of what haunts Amin, though now living a pleasant life in the Danish countryside, is the fact that he was once sternly instructed never to disclose that his family members were still alive, for fear of endangering his refugee status. Deeply feeling the debt he owes to his elder siblings, who risked their own happiness to secure his future, he can’t get past a strong sense of guilt and thwarted obligation.

It's partly to protect Amin’s identity that his story is told through animation, with the tale’s actual hero never appearing on screen. The framing device is simple: a graphic version of the adult Amin, often staring straight forward as if into the lens of a camera, haltingly discloses the twists and turns of his life to his filmmaker-friend. Rasmussen’s gentle questions lead us into enactments of various segments of the life Amin is recalling. What’s striking is the way the style of animation shifts from scene to scene. Family members are portrayed hyper-realistically—we see beard stubble and adolescent skin blemishes—and the characters are often set against backdrops that are nearly photographic in their realism. Then, as disaster strikes yet again, the animator’s palette shifts briefly into blacks and greys, with fleeing figures looking almost ghostly as they butt up against enemies both human and metaphoric. There are also interspersed moments of documentary photography, showing the crowded streets of Kabul, the gloomy byways of Moscow, the bright lights and skyscrapers of New York City.

It's not all gloom. We experience the swirling excitement of a Swedish gay bar (yes, that’s another aspect of the challenges Amin faces), and we also revel in the peaceful landscape of Denmark. And sound design too contributes to the kaleidoscopic effect: we hear actual clips from newscasters and politicians, and Amin (especially in childhood) finds a happy, though short-lived, retreat in the American pop music that blasts through his headphones.

Flee is an artistic tour-de-force, while also being a provocative look at one man’s personal refugee crisis. No wonder the film has won so many critics’ awards, and seems likely to be nominated for Oscars in more than one category. It’s, at one and the same time, a foreign language feature, a hard-hitting documentary, and an animated film that’s worthy of going up against Pixar’s usual brilliance. And if you watch Flee—for a while, at least—your thoughts of COVID will be far away.

January 18, 2022

A Stroll Down Nightmare Alley: The Deceiver Deceived

Director Guillermo del Toro is in love with the fantastic and the macabre. Sometimes his grotesque figures turn out to be benign, even heroic, as is the case with his sexy aqua-man in the Oscar-winning The Shape of Water. In the magnificent Pan’s Labyrinth, a girl in retreat from the brutality of everyday life finds solace in the make-believe world of magical creatures. In his new Nightmare Alley (based on a 1946 novel that was previously filmed in 1947 with Tyrone Power in the central role), del Toro turns to film noir stylistics to explore the surreal lives of carnival folk. One big difference from his previous work: in this film the magical tricks and stunts all are given logical explanations. Though they seem eerily supernatural, they’re in fact 100% bogus. Each is cleverly designed to fake out the credulous, all the better for unscrupulous men (and women) to exploit their “marks.”

The setting for most of Nightmare Alley (probably too much, given the film’s excessive length), is a seedy traveling carnival, circa 1940. It’s the depths of winter: snow, slush, and torrential rain are constant reminders that the natural world can be harsh indeed. Into a tumble-down tent stumbles Stanton Carlisle (Bradley Cooper), a man who’s clearly seen better days. He’s desperate for work and a sense of belonging. Soon he’s part of a team led by the carnival’s owner, played by the always sinister Willem Dafoe. Among Stan’s new comrades are midgets, fortune-tellers, a pretty young woman who conducts electricity through her body, assorted freaks, and (literally) geeks. (If you don’t know the grotesque original meaning of that currently popular term, you’ll certainly learn it here.)

Though the season remains winter, matters considerably heat up when Stan falls for Molly, the electric girl (Rooney Mara), and takes the tricks he’s learned as a carny into the wider world. Quickly he evolves into “The Great Stanton,” charming uptown folks with a flashy mentalist act in which he divulges secrets and facilitates conversations with the dead. The point seems to be that credulity knows no boundaries of class or economic status. Wealthy, powerful men approach Stan, desperate to initiate contact with lost loved ones. Stan is, of course, more than happy to oblige, though the results are not quite what he anticipates. I will not go into the role played here by the protean Cate Blanchett (so very different from the flashy TV host she plays in the current Don’t Look Up.), except to say that it reinforces the movie’s overall theme: that no one can really be trusted. It should not surprise us that when the film’s ending finally rolls around, Stan’s essentially back to where he started, with one grim difference. At least he’s wised up enough to know where he stands in the carny hierarchy . . . and in the universe.

Nightmare Alley is effective, if you know in advance you’re in for a long sit. In addition to Bradley Cooper (who dynamically conveys his character’s weaknesses as well as his strengths), the carnival folk include such reliable presences as Toni Collette (as Zeena the Seer), David Strathairn (as her hapless husband Pete), and Ron Perlman (as Molly’s hulking guardian figure). The world of the rich is inhabited by Mary Steenburgen (in a poignant and ultimately shocking small role) and an almost-unrecognizable Richard Jenkins, a del Toro favorite. Visually, the seedy carnival world, juxtaposed with the art deco elegance of Cate Blanchett’s office, is not easily forgotten. It’s the stuff that can haunt your dreams.

January 14, 2022

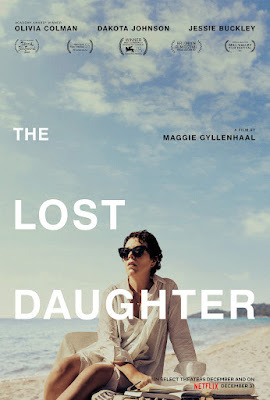

Finding The Lost Daughter (or "Leda and the Swain")

The slyness of The Lost Daughter is part of its attraction. This film, based on a novel of the same name by Italy’s mysterious Elena Ferrante, does contain as an important plot strand a little girl who strays from the Greek beach where her parents are enjoying sun and sand. But mostly this is the story of a mother who feels lost. Or, at least, a mother who is continually questioning her own behavior, past and present.

The film, effectively helmed by Maggie Gyllenhaal in her directorial debut, shifts artfully between past and present. The Leda of the past (her name is a nod to Greek mythology and the poetry of Yeats) is a frazzled young wife and mother who resents the intrusions of her two rambunctious young daughters as she struggles to translate English verse into Italian. The Leda of the present—the one who occupies the central position in the film—is a highly placed professor of comparative literature. Loaded down with heavy books, she arrives at an oceanside resort town in Greece, for what she terms a working holiday.

This older Leda, on the cusp of middle-age, is sometimes hard to fathom. As played by the always watchable Olivia Colman, she sometimes seems to be joyously drinking in the spirit of her new surroundings. The beach is enticing, the caretakers who work in the area are friendly, and she responds with amiable politeness to everyone she meets. But there’s another side to her too: she can throw us off balance with a sudden rude remark, and there’s something about the big noisy family group that encamps near “her” spot on the beach that is clearly setting her off. Some reviewers, seemingly determined to make the film into a suspense thriller, emphasize the mysteries of Leda’s behavior as though this were an episode of Murder, She Wrote. No, it’s actually more of an in-depth character study of a woman who recoils from others partly because she’s recoiling—unsuccessfully—from herself.

The most baffling aspects of Leda’s behavior involve a child’s doll, a rather scruffy plaything beloved by the little girl whose brief disappearance gives the story its title. While being the one to locate the missing child, Leda secretly holds onto her doll, even as the girl’s family desperately searches for its whereabouts. Why? Many smart people I know are debating this question. But I believe the answer is hidden in those flashbacks, in which another well-loved doll, essentially a family heirloom, makes an appearance. The contradictory things Leda does in the present are inextricably linked to her behavior in the past, as a young mother (well played by Jessie Buckley) torn between her various responsibilities and her flagging sense of self.

Because the true identity of the pseudonymous Elena Ferrante remains a mystery among literary types, some have speculated that “she” is actually a male author. I have no way of knowing, but based on the contents of this film I’d say that Ferrante, like Maggie Gyllenhaal, knows at first hand what it’s like to go through life as a female. Women who’ve raised children have a special insight into the tug-of-war between motherhood and self-preservation. Leda, it seems clear, loved (and still loves) her daughters, but has also spent her life fighting to hold onto a personal identity that doesn’t always have room for their daily demands. An intellectual woman, one whose ambitions stretch far beyond hearth and home, is not always satisfied with playing the familial caretaker role. No wonder the younger Leda fell so catastrophically for someone who admired her for her mind.

January 11, 2022

The Importance of Being Sidney (Poitier)

How well I remember the evening in 1964 when Sidney Poitier became Hollywood’s first African American winner of the Oscar for Best Actor. The film was Lilies of the Field, in which he played a wanderer in the parched American Southwest who is persuaded by some feisty German nuns to build a chapel for the glory of God. It’s a charming movie, one that could raise few hackles among those who were made uneasy as the Civil Rights Movement built up steam. My parents and I were thrilled that the film industry had gotten it right, giving its highest honor to someone who so clearly symbolized social progress.

It wasn’t Sidney Poitier’s fault that he was the right man at the right time. Starting in the late 1950s, Hollywood was realizing that African Americans should be seen as more than Pullman porters, shoeshine boys, and lazy household retainers in the Stepin Fetchit mold. Tall, handsome, and ebony-skinned, Poitier fit naturally into hero roles, and had neither opportunity nor inclination to try for a broader range of parts, such as those that later Black actors like Denzel Washington have enjoyed. Even while playing an escaped convict in Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones (1958), Poitier displayed a natural nobility that inspired white audiences while sometimes annoying Black intellectuals. James Baldwin noted in The Devil Makes Work how “liberal white audiences applauded when Sidney, at the end of the film, jumped off the train in order not to abandon his white buddy. The Harlem audience was outraged, and yelled, ‘Get back on the train, you fool!’”

Karen Kramer, who became close to Poitier through her director-husband, admits that, off-camera, Poitier “didn’t know where he belonged. He was not completely accepted by the white community, and he was stepping out of bounds with the black community. So he was in limbo there.” Rod Steiger, Poitier’s In the Heat of the Night co-star, later revealed how Poitier chafed at being designated the Prince of his People: “They put this image on him, for chrissake. He couldn’t yell, couldn’t swear, couldn’t do anything, ‘cause he was the prince of the black race.” This awkward label made Poitier jealously guard his private hours, and contributed to his hypersensitivity about his reputation with the moviegoing public.

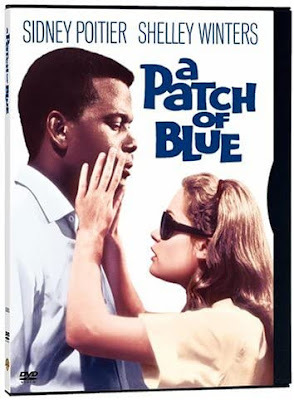

By the mid-Sixties, Poitier’s roles invariably showcased a man alone, set apart from society by the color of his skin. Never was he allowed such basic things as romance or even sexual urges. In 1965 he twice starred opposite gifted white actresses: Elizabeth Hartman as a needy blind girl in A Patch of Blue; Anne Bancroft as a suicidal matron at the other end of a telephone hotline in The Slender Thread. In both films he shows compassion, but also physical detachment. In the Heat of the Night makes it clear, in a key scene, that he’s a loner, a cop married to his job.

In the banner year 1967, when Poitier was Hollywood’s biggest box office draw, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner fomented even more ire among Black viewers, because it celebrated their Sidney as the unexpected fiancé of a (rather vapid) white woman. The film prompted a young Black playwright, Clifford Mason, to publish in the New York Times a scathing take-down titled “Why Does White America Love Sidney Poitier So?” Recently Mason explained to me his vitriol toward Poitier as an outgrowth of dashed expectations. He’d hoped for a leading Black actor who could truly tackle the hard issues. Mason now phrases his disappointment in movie terms: “I wanted Bogart, but all I got was Cary Grant.”

January 7, 2022

Peter Bogdanovich Has Come and Gone

Well, we just lost another of those daring young men who made the Hollywood films of the 1970s so exciting. Peter Bogdanovich is gone, at age 82. He broke into the industry quite young, causing many movie historians then and now to compare him to another “boy genius,” Orson Welles. Clearly relishing the comparison, he wore ascots, cultivated friendships with some of the greats of the Golden Age, and shot two of his best films (The Last Picture Show and Paper Moon) in living black & white.

When I think of Bogdanovich, though, Orson Welles doesn’t come to mind. Instead I remember Roger Corman, my former boss, as the man who gave Bogdanovich his first big break. The story has been told many times, but I much prefer the version of Polly Platt, Bogdanovich’s first wife, his creative partner, and the woman he dumped for Cybill Shepherd on the set of The Last Picture Show. Polly, who passed away in 2011, spoke to me at length three years earlier, about how Roger jumpstarted the movie careers of two young east-coasters who were passionate about the film medium.

Peter and Polly first met Roger Corman at a screening. (She thinks it was Last Year at Marienbad.) Afterwards, they chatted about film over coffee, and Roger was obviously impressed by their determination to find careers in the industry. In her words,

They were also all-purpose assistant when Roger directed his biker classic, The Wild Angels. Peter, who mid-production finagled the job of second-unit director, has said, “I went from getting the laundry to directing the picture in three weeks. Altogether, I worked twenty-two weeks—pre-production, shooting, cutting, dubbing—I haven’t learned as much since.” (Polly worked alongside him on a script rewrite, and also found herself doubling on the back of a chopper for female lead Nancy Sinatra.)

The reward came when Roger approached them with another challenge. Actor Boris Karloff owed him two days of work from an earlier film, The Terror. This had been one of Roger’s lesser flicks, and they were free to use its footage along with new material to make a horror movie of their own. It was Polly, still traumatized by the JFK assassination, who came up with the concept of a sniper running amok at a drive-in movie theatre. They collaborated on the script; Peter directed the film while also playing a key role. With the release of Targets in 1968. his Hollywood career was fully launched.

Nor did Bogdanovich’s relationship with Corman end there. As my former colleague, filmmaker Joe Dante, once told me, “The thing about Roger is that you meet him on the way up, and if you’re not lucky you meet him again on your way down.” In 1979, while Bogdanovich was in a downward spiral, Roger hired him to shoot Saint Jack, about an American hustler in Singapore.. Dante remembers, “It turned out to be a good picture, and it put him back on the road.”

January 4, 2022

Loving Lucy; Leaving Desi

Lucille Ball was a comic genius, and Desi Arnaz wasn’t far behind. That’s something of which I’ve been sharply reminded recently, while watching early I Love Lucy re-runs to welcome in the new year. Lucy’s subversion of the “happy homemaker” trope worked for me as a kid growing up in a house with a brand-new TV set. And over a decade later, while a student in Tokyo, I watched with delight as my roommate’s young nephews roared with laughter at Lucy’s antics, dubbed into Japanese.

Despite the joyousness of the sitcom, which ran from 1951 to 1957, most of us know there were cracks in the Ball/Arnaz marriage that kept widening even while the show that celebrated a fictive version of their union was a high-flying hit. Desi may have truly loved Lucy, but his obsessive philandering (coupled with chronic alcoholism) led Ball to file for divorce in 1960, once their last show together was in the can. Given the two stars’ vivid personalities and their long-range impact on Hollywood, it made sense for Aaron Sorkin to undertake a film about the ups and downs of their lives together. And it seems smart of Sorkin, an award-winning screenwriter before he took up directing, to use as his structural framework the week leading up to a particularly fraught live taping of I Love Lucy.

There’s nothing like a ticking clock to enhance a film’s dramatic appeal. In Being the Ricardos, we move through a fall 1953 work-week, Monday through Friday, in which a new episode of the show is written, rehearsed, and put on its feet before a live studio audience. Aside from the usual artistic pressures, this particular week presents an enormous challenge, because a blind item in Walter Winchell‘s column has pegged Ball as a member of the Communist Party. Given the political pressures of the era, if the rest of the media turn against her now, the popular TV series will be no more. This possibility hangs over the taping of the episode, while Ball herself pays more attention to another newspaper item, one emphatically implying Desi’s marital infidelity. This is strong stuff, and it leads to a climax that works wonderfully well, combining both victory (Ball’s patriotism is endorsed by her fans) and defeat. It’s the matter in between that I find problematic.

Though Sorkin appears to have whittled down his Ball/Arnaz saga to one climactic week, he stuffs that week so full of hot-button issues that we can barely keep up. To wit: in and around the tensions provoked by the news items, Lucy and Desi announce she’s expecting a baby. This wasn’t historically true of the week in question, and the pregnancy contributes nothing of value to the specific story being told, though it allows us to see Desi’s clout when he demands that the pregnancy be worked into the show, in defiance of previous TV industry mores. Ball gets a feminist rant too, in support of her Lucy character. And Sorkin jumps outside the structure he’s set up in other ways, adding flashback to earlier points in the life of the couple (their first date, her evolution into a redhead, her insistence that Desi—not some white guy—play her husband on her new TV show). We leap into the future too, with the three key members of the I Love Lucy writing team—now much older and played by different actors—looking back on the implications of that frenzied week as well. The result is a tangle, one that some bravura performances (particularly by J.K. Simmons as William “Fred Mertz” Frawley) can’t unsnarl.

For those who’ve seen the film, here’s an L.A. Times breakdown of how well it jibes with the historical facts of the Desi/Lucy relationship.

December 31, 2021

Restoring (and Rescoring) ���West Side Story���

What does it take to remake the beloved 1961 musical, West Side Story? I���d say it requires two things: chutzpah and cojones. And Steven Spielberg has plenty of both. As a lover of the original film, which won ten Oscars in 1962, Spielberg sought to preserve the greatness of the original. But he clearly saw a need to re-contextualize a story (of feuding street gangs and a forbidden love affair) that has come to seem hackneyed over time.

When the stage musical that melded the talents of Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim, Arthur Laurents, and Jerome Robbins first burst onto the Broadway scene in 1957, the contemporary take on Shakespeare���s Romeo and Juliet seemed bold and fresh. Years later, though, we can���t ignore the creakiness of the material. And today���s sensibilities aren���t comfortable with the casting of Anglos in dark makeup as Latinos. (In the 1961 film version, the supposedly Puerto Rican Sharks gang was comprised of dancers from as far afield as Japan. Though Rita Moreno was genuinely born���like her character���in Puerto Rico, fellow Oscar winner George Chakiris is of Greek descent. Nor was Natalie Wood a PC choice to play the film���s romantic heroine,)

Along with correcting the casting faux-pas of the original film, Spielberg gave his version a sense of the historical forces at play. New York City, circa 1960, was a place where slums were being noisily demolished to make room for Lincoln Center. In the opening, we spot at a construction site an idyllic sketch of the theatres and concert halls that will soon be springing up. A cop-character tasked with keeping order among the slum-dwellers drives the point home: one day the area will be filled with glitzy apartments owned by wealthy whites. Any Puerto Ricans still in the vicinity will be doormen and maids. And the feckless white kids who make up the Jets will continue to descend the social ladder, crowded out of their own turf first by immigrants, then by gentrification.

I give playwright Tony Kushner full credit for fleshing out many characters, hinting at backstories for Jets like Tony and Riff, while also showing the aspirations of the immigrant Sharks. (Bernardo in this version is an up-and-coming boxer.) Fresh attention is paid to the women, who are given far more heft and dignity than in the previous film. Anita (at least sometimes) campaigns against the violence of the street gangs, Maria is less of a delicate flower than previously, and there���s an important moment late in the film when the women on opposite sides of the conflict are seen trying to look out for one another. The major addition to the familiar plot is a brand-new character, Valentina. Played by Rita Moreno, now an astonishing 90, she fills the function of Doc, the sympathetic Jewish drugstore owner of the first film. We learn she is Doc���s widow, a living example of how an interracial couple could thrive even in these fraught surroundings. As Tony���s confidante, she is in an ideal position to project the fundamental optimism behind the whole project, that SOMEWHERE there���s a place where love can survive.

This new film is hardly perfect. There are a few serious gaps in plot logic, and the distinctive personalities of the Jets (so memorable in the earlier film) get lost here. I appreciate, though, the bleaker, tougher visuals, as well as the smart new use of the song ���Cool��� to lead into the climactic rumble. I suspect, though, that the new film will never have the same power for its audiences as the one I thrilled to back in 1961.

Restoring (and Rescoring) “West Side Story”

What does it take to remake the beloved 1961 musical, West Side Story? I’d say it requires two things: chutzpah and cojones. And Steven Spielberg has plenty of both. As a lover of the original film, which won ten Oscars in 1962, Spielberg sought to preserve the greatness of the original. But he clearly saw a need to re-contextualize a story (of feuding street gangs and a forbidden love affair) that has come to seem hackneyed over time.

When the stage musical that melded the talents of Leonard Bernstein, Stephen Sondheim, Arthur Laurents, and Jerome Robbins first burst onto the Broadway scene in 1957, the contemporary take on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet seemed bold and fresh. Years later, though, we can’t ignore the creakiness of the material. And today’s sensibilities aren’t comfortable with the casting of Anglos in dark makeup as Latinos. (In the 1961 film version, the supposedly Puerto Rican Sharks gang was comprised of dancers from as far afield as Japan. Though Rita Moreno was genuinely born—like her character—in Puerto Rico, fellow Oscar winner George Chakiris is of Greek descent. Nor was Natalie Wood a PC choice to play the film’s romantic heroine,)

Along with correcting the casting faux-pas of the original film, Spielberg gave his version a sense of the historical forces at play. New York City, circa 1960, was a place where slums were being noisily demolished to make room for Lincoln Center. In the opening, we spot at a construction site an idyllic sketch of the theatres and concert halls that will soon be springing up. A cop-character tasked with keeping order among the slum-dwellers drives the point home: one day the area will be filled with glitzy apartments owned by wealthy whites. Any Puerto Ricans still in the vicinity will be doormen and maids. And the feckless white kids who make up the Jets will continue to descend the social ladder, crowded out of their own turf first by immigrants, then by gentrification.

I give playwright Tony Kushner full credit for fleshing out many characters, hinting at backstories for Jets like Tony and Riff, while also showing the aspirations of the immigrant Sharks. (Bernardo in this version is an up-and-coming boxer.) Fresh attention is paid to the women, who are given far more heft and dignity than in the previous film. Anita (at least sometimes) campaigns against the violence of the street gangs, Maria is less of a delicate flower than previously, and there’s an important moment late in the film when the women on opposite sides of the conflict are seen trying to look out for one another. The major addition to the familiar plot is a brand-new character, Valentina. Played by Rita Moreno, now an astonishing 90, she fills the function of Doc, the sympathetic Jewish drugstore owner of the first film. We learn she is Doc’s widow, a living example of how an interracial couple could thrive even in these fraught surroundings. As Tony’s confidante, she is in an ideal position to project the fundamental optimism behind the whole project, that SOMEWHERE there’s a place where love can survive.

This new film is hardly perfect. There are a few serious gaps in plot logic, and the distinctive personalities of the Jets (so memorable in the earlier film) get lost here. I appreciate, though, the bleaker, tougher visuals, as well as the smart new use of the song ‘Cool” to lead into the climactic rumble. I suspect, though, that the new film will never have the same power for its audiences as the one I thrilled to back in 1961.

December 29, 2021

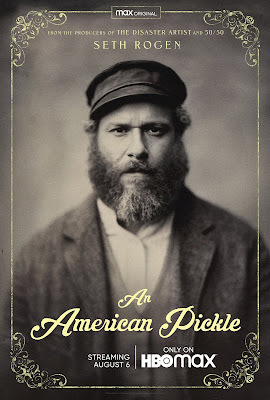

New York Jews in a Pickle: ���Shiva Baby��� and ���An American Pickle���

For those who���ve been desperately waiting for the return of Mrs. Maisel, have I got a movie (or two) for you? Mrs. Maisel, of course, is the much-honored TV sitcom involving the adventures, romantic and otherwise, of an upscale New York Jewish family. Set in the youthful, idealistic, and all-too-brief Kennedy era, it focuses on an affluent young wife and mother struggling to make her way as a stand-up comedian.

On a recent much-delayed flight (don���t ask!), I watched two movie comedies that make full use of Jewish gallows humor. The first features the sort of kvetchy, semi-stereotypical New York Jewish mamas of whom Mrs. Maisel makes full use. But Shiva Baby, written and directed by a young woman not long out of NYU���s Tisch School of the Arts, unfolds very much in the present day. A shiva, the traditional gathering following a Jewish funeral, is generally a place where long-lost friends and relatives re-connect in an atmosphere of familial warmth. But the shiva at the heart of this film contains more than a few outrageous surprises. Its protagonist is Danielle, an appealing but clearly unmoored recent college graduate, who has found a rather unsavory way to get by in life. Urged by her parents to show up out of respect for the family of the deceased, she���s shocked to encounter, over a plate of gefilte fish, the person she least wants to see. And he turns out to be an old friend of her father too! It���s basically an oddball comedy of manners, with such issues as gender identity and eating disorders thrown into the mix. (The implications of the title only become fully clear at the film���s tail-end.) A small indie, well-cast and well-filmed, of the sort that promises big careers down the line.

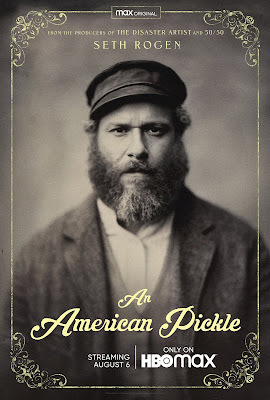

Then there���s An American Pickle, another 2020 movie (this one an HBO production) that didn���t make much of a splash. It contains some of the outrageousness of Borat, along with an underlying sweetness that has stayed with me. Yes, the star is perennial bad boy Seth Rogen, but sex and weed don���t make an appearance. Rogen first appears as Herschel Greenbaum, an old-world ditch-digger with a big beard and a Tevye-type accent. When Cossacks destroy his shtetl on the night of his wedding to his beloved Sarah, the two of them boldly set out for New York, where he finds work in a pickle factory. But his life in America will soon be changed forever, once he falls into a vat of pickle brine that will preserve him for a century.

Discovered and resuscitated in 2019, Herschel learns that his only living relative is a great-grandson. Ben, also played by Rogen, is a bit of a geek, a good-hearted but rather wimpy computer nerd working on an app with which he hopes to make his fortune. Ben welcomes Herschel into his life, but their differences create a strain between them. The mild-mannered Ben finds it hard to handle Herschel���s emotional nature, which includes a fondness for making ���big violence��� whenever his highly non-PC opinions are challenged. Once Herschel starts producing and bottling scrounged Kosher dills in a way that the nation���s foodies regard as ���artisanal,��� Ben can���t contain his jealousy. Hilarity ensues. I realize that critics have been hard on this film, and it���s true that its silliness is sometimes overplayed. But I���ll remember the genuine schmaltz of the moments when family feelings win out. And when was the last time you saw a film that sincerely exalts the power of prayer as a way to cope with tragedy?

New York Jews in a Pickle: “Shiva Baby” and “An American Pickle”

For those who’ve been desperately waiting for the return of Mrs. Maisel, have I got a movie (or two) for you? Mrs. Maisel, of course, is the much-honored TV sitcom involving the adventures, romantic and otherwise, of an upscale New York Jewish family. Set in the youthful, idealistic, and all-too-brief Kennedy era, it focuses on an affluent young wife and mother struggling to make her way as a stand-up comedian.

On a recent much-delayed flight (don’t ask!), I watched two movie comedies that make full use of Jewish gallows humor. The first features the sort of kvetchy, semi-stereotypical New York Jewish mamas of whom Mrs. Maisel makes full use. But Shiva Baby, written and directed by a young woman not long out of NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, unfolds very much in the present day. A shiva, the traditional gathering following a Jewish funeral, is generally a place where long-lost friends and relatives re-connect in an atmosphere of familial warmth. But the shiva at the heart of this film contains more than a few outrageous surprises. Its protagonist is Danielle, an appealing but clearly unmoored recent college graduate, who has found a rather unsavory way to get by in life. Urged by her parents to show up out of respect for the family of the deceased, she’s shocked to encounter, over a plate of gefilte fish, the person she least wants to see. And he turns out to be an old friend of her father too! It’s basically an oddball comedy of manners, with such issues as gender identity and eating disorders thrown into the mix. (The implications of the title only become fully clear at the film’s tail-end.) A small indie, well-cast and well-filmed, of the sort that promises big careers down the line.

Then there’s An American Pickle, another 2020 movie (this one an HBO production) that didn’t make much of a splash. It contains some of the outrageousness of Borat, along with an underlying sweetness that has stayed with me. Yes, the star is perennial bad boy Seth Rogen, but sex and weed don’t make an appearance. Rogen first appears as Herschel Greenbaum, an old-world ditch-digger with a big beard and a Tevye-type accent. When Cossacks destroy his shtetl on the night of his wedding to his beloved Sarah, the two of them boldly set out for New York, where he finds work in a pickle factory. But his life in America will soon be changed forever, once he falls into a vat of pickle brine that will preserve him for a century.

Discovered and resuscitated in 2019, Herschel learns that his only living relative is a great-grandson. Ben, also played by Rogen, is a bit of a geek, a good-hearted but rather wimpy computer nerd working on an app with which he hopes to make his fortune. Ben welcomes Herschel into his life, but their differences create a strain between them. The mild-mannered Ben finds it hard to handle Herschel’s emotional nature, which includes a fondness for making “big violence” whenever his highly non-PC opinions are challenged. Once Herschel starts producing and bottling scrounged Kosher dills in a way that the nation’s foodies regard as “artisanal,” Ben can’t contain his jealousy. Hilarity ensues. I realize that critics have been hard on this film, and it’s true that its silliness is sometimes overplayed. But I’ll remember the genuine schmaltz of the moments when family feelings win out. And when was the last time you saw a film that sincerely exalts the power of prayer as a way to cope with tragedy?

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers