Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 41

November 19, 2021

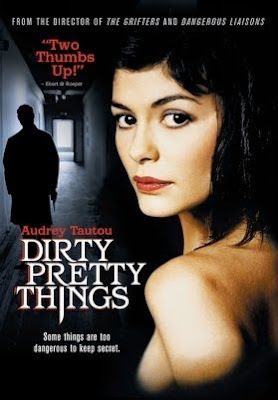

Finding the Beauty in “Dirty Pretty Things”

Stephen Frears doesn’t take on simple projects. Working on both sides of the Atlantic, the British director seems to prefer stories with dense textures, in which people with clashing goals and social expectations are forced by circumstances to work together. One of my favorites, dating back to 1985, is My Beautiful Laundrette, which confronts racial and sexual taboos in contemporary working-class London. (The film was my introduction to Daniel Day-Lewis, and I won’t soon forget his portrayal of a gay street punk.) Five years later, with an American cast that introduced Annette Bening to the world, Frears explored the world of con artists and nabbed an Oscar nomination for The Grifters. Other notable Frears projects include Dangerous Liaisons, High Fidelity, and The Queen.

Just recently I caught up with 2002’s Frears-directed Dirty Pretty Things, a powerful English film that’s easier to admire than to adore. It’s, among other things, a love story, but not in the way of some of the American films I’ve borrowed from my library of late (like, for instance, the Christmas-y Sandra Bullock vehicle, While You Were Sleeping). That odd, oxymoronic title says a lot: there are pretty things, and pretty people, within Frears’ movie, but the world it depicts is full of dirt, blood, and shame.

This is hardly the sedate London we Americans tend to think of: a place of royalty, ridiculous hats, tea and crumpets. Instead, Frears probes the underbelly of the multi-ethnic city, where immigrants are so desperate for money and for legal papers that they’ll do almost anything that’s asked of them. Chiwetel Ejiofor, worlds away from his role as Lola in 2005’s Kinky Boots, plays Okwe, a Nigerian doctor who, through a series of ugly political circumstances, now works around the clock as both a cab driver and the night clerk at a London hotel. (He nibbles on khat, supplied at a local ethnic market stall, to stay awake.) Okwe shares lodgings with Senay, a modest young Muslim room-cleaner (played, with surprising conviction, by Audrey Tatou of Amélie fame), who’s determined to hold onto her shaky status as a legal immigrant from Turkey. Both Okwe and Senay inevitably find themselves at the mercy of the hotel manager, a conniving Spaniard. He runs a racket providing passports and new identities for illegals who agree to pay a terrible price. What the undocumented are willing to risk for the sake of questionable legal papers is both grotesque and heart-breaking, and we believe every word of it.

But by its conclusion Dirty Pretty Things has become less a social polemic than a thriller. There are twists within twists, ensuring that the sinister Londoners we’ve seen in action will eventually get their comeuppance. Still, though Okwe and Senay overcome some serious hurdles and find their lives dramatically changing, we’re not at all sure by the final fadeout that they are finally on the right track. There’s no talk of a sequel, but I for one don’t want to let these characters go. They’re complex enough, especially after the choices they make in the course of this drama, to entitle us to wonder: What comes next?

Dirty Pretty Things received some major accolades, climaxing in an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay. (It was a great year for small films, and the ultimate winner in this category was Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation.). Ejiofor, who despite his exotic name is London-born, won acclaim in 2013 for his leading role in 12 Years a Slave. But I hail him for his sad, angry, gentle, cowardly, brave portrayal of Okwe in this film.

November 16, 2021

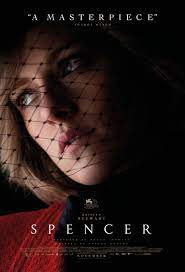

“Spencer”: A Royal Family to Die For

What do I think of the late Princess Diana? I’m not what you’d call heartless; though I hardly qualify as a someone obsessed with the ins and outs of royal families, both Diana’s triumphs and her tragedies have always struck me as deeply touching. Why, then, did I find myself sitting restlessly through Kristen Stewart’s acclaimed portrayal of Diana in Spencer, muttering “Get a grip!”?

No question that Lady Diana Spencer got a raw deal. I recall the excitement when this virginal young pre-school aide was announced as the bride-to-be of Britain’s Prince of Wales. After a fairytale wedding and the birth of two sons (“an heir and a spare”), it became painfully clear that Prince Charles was otherwise engaged. I’ll say this for Charles: he seems to be the picture of constancy. Both then and now, the only true woman in his life (aside from his mother, the queen) has been Camilla Parker Bowles, the divorcee who was finally able to marry her longtime lover in 2005.

What was most appealing about Diana in her lifetime was her common touch: her ability to connect with people on the lower end of the social spectrum. From all reports, the coldness of the House of Windsor toward her reflected a sense that she, and not they, had won the hearts of the populace. Not surprisingly, she was at her worst when surrounded by stuffy royal protocol, as during the three days the film depicts. Aside from certain flights of fantasy, it’s set mostly in the royal residence at Sandringham House, Norfolk, where the Windsors have retreated to celebrate the Christmas holidays with what for them passes for “a bit of fun.” (Schedules are strictly followed; lavish meals are served with military precision; every guest must be weighed on an antique scale both upon arrival and when leaving. This last is a custom instituted in the 19th century by Queen Victoria’s consort, Prince Albert, to prove that all visitors have eaten heartily, thereby gaining an appropriate amount of weight.)

As depicted on-screen, Diana is fully aware that her marriage is a sham. Even her Christmas gift from Charles, a massive pearl necklace, is identical to the one he has purchased for Camilla. Arriving late and alone (thereby violating several taboos at the outset), she neglects to draw the drapes of her suite when changing clothing, thus earning a reprimand from the Veddy Military house equerry (Timothy Spall), who warns about paparazzi swarming the vicinity. And she’s not happy at all with the dresser assigned to her, nor with the outfits pre-selected for the various dining activities. Though we’re told that the staff quietly sympathizes with her plight, she hardly makes their work any easier when she rejects a chambermaid’s ministrations and scurries to the pantry to gorge after-hours on the sweets she won’t touch at the table. Her personal anguish is almost her entire focus, to the point where she’s fantasizing about her ancient kinswoman Anne Boleyn, the one-time bride of Henry VIII. (Hey, Diana’s lot may be difficult, but no one’s planning to chop her head off!)

This Diana blossoms only when she interacts with her two adoring young sons. Their scenes together are the film’s best, practically the only ones that show Diana’s capacity for warmth. But mostly she suffers, suffers, suffers. (As did I, in watching.) Director Pablo Larrain captures strong visual moments, but is overly in love with symbols: that pearl necklace, the jacket on a scarecrow, the beautiful plumage of a dead pheasant. Three days at Sandringham at Christmas? I can think of worse kinds of torture.

November 12, 2021

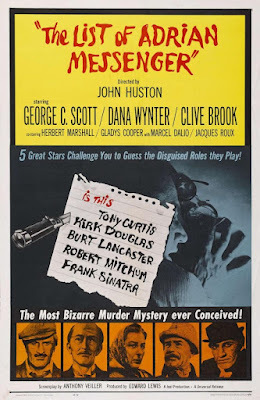

Listing the Deceptions in “Adrian Messenger”

The List of Adrian Messenger, directed by John Huston in 1963, begins with a joke on the audience. We just don’t know, until the film is practically over, where it’s going. The film begins in classic thriller style, with a mysterious old man casing an ornate bank building that is closed for the night. Slipping inside the darkened lobby, he manipulates some levers, and an elevator comes crashing down. Someone, we gather, has just plunged to his death. Whereupon the old man slips out into the darkness and disappears.

The List of Adrian Messenger, directed by John Huston in 1963, begins with a joke on the audience. We just don’t know, until the film is practically over, where it’s going. The film begins in classic thriller style, with a mysterious old man casing an ornate bank building that is closed for the night. Slipping inside the darkened lobby, he manipulates some levers, and an elevator comes crashing down. Someone, we gather, has just plunged to his death. Whereupon the old man slips out into the darkness and disappears.

When the main titles come up, we’re surprised to see (against a swirling backdrop of distinctive faces) the names of some of the biggest male Hollywood stars of the mid-century: Tony Curtis, Kirk Douglas, Burt Lancaster, Robert Mitchum, Frank Sinatra. Then there’s another card: Starring George C. Scott. Say what? As we launch into a classic whodunit in which Scott (using an unconvincing British accent) investigates his friend’s death after a mysterious plane crash, the movie seems to be all about unearthing a revenge plot that may date back to the Burma campaign in World War II. But of course for the viewer the real mystery is this: when are those famous movie stars going to make an appearance?

This was the era when Hollywood studios were desperately looking for ways to counteract the rising popularity of television. One idea was to dazzle potential moviegoers with spectacle; another was to give glimpses of major celebrities, the sort who wouldn’t be caught dead appearing on TV. I well remember the brouhaha surrounding the 1956 release of Around the World in Eighty Days, a blockbuster that was named Best Picture at the Oscars but is virtually unwatchable today. (I saw it at the Carthay Circle, an ornate movie palace that – alas – has long since been replaced by an office building. There were fancy theatre programs in the lobby, and even a special curtain designed to show off in comic fashion the movie’s various thrills.) This elaborate telling of the classic Jules Verne adventure tale, with David Niven in the leading role and a young Shirley MacLaine as the Indian (!) lovely he rescues, was not considered enticing enough to lure Fifties audiences. Instead, the film is crammed with 48 celebrity cameos – hey look! There’s Sinatra at the piano in that saloon! And Marlene Dietrich at a table!

Buoyed by the film’s success, other movies reached for the same gimmick. I remember something called Pepe, starring the Mexican comic Cantinflas, who’d been introduced to the English-speaking world as Phileas Fogg’s sidekick in Around the World in Eighty Days. In Pepe (1960) he journeys to Hollywood to retrieve a beloved horse, giving him the opportunity to hobnob humorously with legendary movie stars. And How the West Was Won (1962) used three directors, heaps of stars, and wide-screen technology to tell a vast frontier tale. But The List of Adrian Messenger is different in that its famous faces are hidden behind elaborate makeup, only to be unmasked just before the final fadeout. Major kudos to Bud Westmore of the long-lived Hollywood family for his false-face designs.

To my disappointment, I’ve learned that the disguised cameos—much touted in the media upon the film’s release—were in some cases total fakes. Yes, we see the celebrities remove their phony faces at the end, but that’s not really Tony Curtis and Burt Lancaster fooling the audience with facial prosthetics and exotic accents. Actor Jan Merlin, a latter-day Roger Corman alumnus, apparently stood in for Kirk Douglas in some of his disguises.

Yes, the laugh’s on us.

November 9, 2021

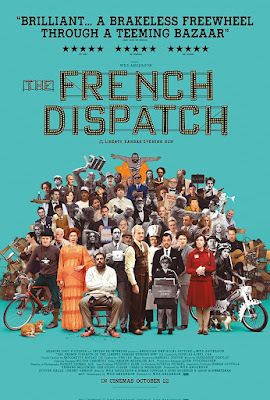

Saying “Oui!” to “The French Dispatch”

It doesn’t pay to try to find deep meaning in a Wes Anderson movie. Anderson leaves it to other filmmakers to confront the world’s great issues. For himself, he’s content to stake out a time and place, add an accumulation of disparate personality types, then infuse everything with a powerful sense of whimsy, heightened by nostalgia for the long-ago and far-away. I took great pleasure in 2014’s The Grand Budapest Hotel, which captured the changing fortunes of a legendary (and of course imaginary) East European hostelry as it moved from periods of peace through years of war. Anderson’s new film, The French Dispatch, seems made of slighter stuff, but it still displays Anderson’s ability to charm, as well as his success at working with a brilliant ensemble cast. Among the glittering hordes who people The French Dispatch are some of screendom’s finest. Bill Murray, Owen Wilson, Tilda Swinton, Benicio Del Toro, Adrien Brody, William Dafoe, and especially Léa Seydoux are among those on full display. Bob Balaban and an unrecognizable Henry Winkler show up as aged uncles. Elisabeth Moss flits by, Saoirse Ronan briefly plays a hooker, and Anjelica Huston does voice-over narration At times it seems you needed to have an Oscar nomination (or an Emmy or at least a César) to join this jolly cast.

Is there a story? Well, sort of. The focus of the film is a literary supplement that’s published as an odd-ball addition to the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun, because the publisher’s offspring is determined to spend his adult life in France. The picturesque French city of Angoulême stands in for the magazine’s home turf, the highly imaginary town of Ennui-sur-Blasé. The heart of the film is three eccentric stories (focusing on true French specialties: art, politics, and cuisine) being researched by Dispatch staffers, all of them American-born Francophiles. Those viewers who are fans of The New Yorker magazine can see how Anderson has wittily woven its history and stylistic quirks into his film. (The New York Times rave review does a splendid job of pointing out the essential parallels, with much reference to the literary greats being parodied on-screen.)

What struck me, though, is how a film ostensibly about the life and times of a cadre of journalists is as much about pictures as it is about the power of words. Visuals, and not just word-pictures, are an essential part of Anderson’s style. One of his three chief stories, that in which Del Toro plays a madman released from bondage when the world discovers his talent for contemporary art, of course has a strong visual element—especially as we see Seydoux evolve into his very naked muse. And the second story, in which crusading reporter Frances McDormand finds herself both politically and sexually moved by student radical Timothée Chalamet, contains priceless images of the two cozily bedded down.

But beyond all this, a key part of Anderson’s stylistics is his delight in cinema as a medium. He loads his frame with every sort of screen gimmick he can get away with: title cards, sudden shifts from color into black & white, unusual camera angles, silent-movie tricks. I see nothing in his biography that suggests a love for stagecraft as well as movies, but the batimênts and byways of Ennui-sur-Blasé are frequently filmed from a distance, as if they were not real locales but rather stage sets constructed out of cardboard and fabric for the spectator’s amusement.

Not every viewer will fall under Anderson’s spell. The review that appeared in the L.A. Times was particularly harsh. But me? I say “Oui!”

November 5, 2021

Laughing (and Shivering) with Charles Laughton

“Hobson’s Choice” is a British expression dating back to Shakespeare’s day. An apparent tribute to a Cambridge livery stable owner named Thomas Hobson (1544–1631)), it implies a choice that turns out to be no choice at all, as in “take it or leave it.” Circa 1916, Hobson’s Choice was a popular British play about a shoe shop owner with three unmarried daughters, The play was ultimately made into several films, in 1920, 1931, and (memorably) in 1954, when the great David Lean—not yet the director of epics like Lawrence of Arabia—turned it into a small, delightful comedy.

In Lean’s film, the role of the demanding, though often drunk, Hobson is played by Charles Laughton, who had already made his mark as King Henry (winning an Oscar for 1933’s The Private Life of Henry VIII), Captain Bligh (in 1935’s Mutiny on the Bounty), and Quasimodo (in 1939’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame). Laughton was a big man with a complicated inner life. (He was married until his death to British actress Elsa Lanchester, but his sexuality remains an open question.) As Henry Horatio Hobson, a shopkeeper in a small Victorian town, he is both charming and dictatorial. He permits his two younger daughters to flirt with their admirers, but tries hard to prevent his eldest from having her own life because—through her efficient running of the shop while he’s off on yet another bender—she’s much too valuable to lose.

But that daughter, Maggie, turns the tables. Tired out from doing all the work and receiving none of the credit, she persuades her father’s #1 cobbler to marry her. Played by John Mills as a talented but self-effacing fellow who’s content to make shoes for a pittance in the basement of Hobson’s shop, he’s a wonderful example of a mouse who ends up roaring. Therein lies most of the comedy, with Mills and his new wife finally making Laughton an offer he can hardly refuse.

Laughton’s deftness at comedy is not called upon in the sole film he’s credited with directing. It was made just one year after Hobson’s Choice, and I chose to see it last Sunday, because it offers spine-tingling Halloween entertainment. The Night of the Hunter, a novel adapted for the screen by James Agee, features Robert Mitchum in one of his creepiest performances. Mitchum plays Harry Powell, a phony preacher who uses his sermonizing and a mellow baritone voice to prey on credulous locals in Depression-era West Virginia. His game is to marry widows, gain access to their nest eggs, murder them with a switchblade in the name of doing the Lord’s work, and go on his way. (He’s based on an actual serial killer hanged in 1932.)

In the film, Mitchum’s character is defined by the tattoos on his fists, one proclaiming LOVE and the other HATE. There’s a recently bereaved young mother (Shelley Winters), and her two small children who know where their dead father hid a cache of money. It’s easy work for Powell to worm his way into the family, marrying the naïve widow and then disposing of her. Now he’s after the kids. There’s also a key role for a member of moviedom’s royalty, Lillian Gish, who had been making movies since 1912. Here her character’s genuine piety makes a vivid contrast with Powell’s phony religious pronouncements.

Laughton chose to shoot the black & white movie in a powerfully expressionistic style, using visual devices from silent film. But he also relies on period music: Mitchum’s warbling of “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms” can’t possibly sound more sinister.

November 2, 2021

Shooting the Breeze about Alec Baldwin and “30 Rock”

30 Rock isn’t exactly what you’d call a brand-new show. This sitcom lampooning the NBC corporate culture and the running of a comedy sketch show lasted seven seasons, from 2007 to 2013. The creation of the multi-talented and hyper-funny Tina Fey, it trades upon Fey’s own experiences as SNL head writer. Fey also plays the role of Liz Lemon, a head writer alternately obsessed with food, liberal politics, finding Mr. Right, and keeping a bunch of misfit comedy writers in line. Throughout much of the series, her chief sparring partner is John Francis Donaghy (Alec Baldwin), a right-wing man-about-town far less interested in cutting-edge comedy than in corporate profits.

During this pandemic, I’ve dived into 30 Rock head first. My initial takeaway is how much 30 Rock reads like an updating of a workplace-comedy classic, The Mary Tyler Moore Show (1970-1977). That show, of course, featured the goings-on behind the scenes of a TV news broadcast, featuring a curmudgeonly boss (Edward Asner), a no-talent star (Ted Knight), an ageing vamp (Betty White as the Happy Homemaker), and assorted wisecracking writers. At the center of the chaos was Mary Richards (Mary Tyler Moore), as the uber-capable all-around assistant who needed to constantly stick up for herself as an unmarried woman. In 30 Rock, the unmarried woman has a great deal more authority, but is still fragile as she desperately juggles the demands of an egotistical star (Tracy Morgan), a boobalicious best friend (Jane Krakowski), and a boss who thinks he’s god’s gift to humanity. And, yes, at times she obsesses over chucking it all and having a baby.

As Jack Donaghy, Alec Baldwin knocks it out of the park as a guy you love to hate. Baldwin may have started in dramatic roles (he’s played Jack Ryan in The Hunt for Red October and Stanley Kowalski in a TV version of A Streetcar Named Desire), but comedy seems to be his true métier. There’s something so slick and sleazy about his look that it’s hard to take him wholly seriously. And he certainly called on his looks and comic flair in his years of lampooning our 45thpresident. At the moment, though, he’s starring in a tragedy he never intended to make. Baldwin is a producer as well as the star of an ill-fated western called Rust, shooting outside Santa Fe, New Mexico. On October 21, Baldwin fired a prop gun during an on-set rehearsal. Though the gun was supposed to be unloaded, it apparently discharged a live bullet that killed cinematographer Halyna Hutchins and wounded director Joel Souza. No one is claiming that the shooting was intentional, but it’s clear from the testimony of the first assistant director and other crew members that basic safety precautions were not being followed. That’s the thing about movies: they require huge cadres of workers who must all understand the ins and outs of their jobs, or else risk dooming the entire production.

The recently averted strike by IATSE, the umbrella union for movie folks, was partly about safety issues. Stars and other actors tend to be respected, even coddled—but crew conditions can be slipshod at best. When I interviewed Oscar-winning cinematographer Haskell Wexler, his great cause was protecting camera personnel who worked such long stretches that some died behind the wheel on their way home from 18-hour days. This happens in Hollywood, and there’s even more danger in out-of-the-way locales where union oversight is spotty or non-existent. .My Roger Corman pals shot films in places where life is considered cheap. But no one should die while making a movie.

October 29, 2021

Food for Fright-Night: The B-Movie Cookbook

It’s almost Halloween, and time to ask What’s Cooking? My experts, of course, are Fiona Young-Brown and her hubby, Nic Brown. I first met Fiona at a serious writers’ conference in New York City; little did I know then that I’d eventually end up as a guest on Nic’s long-running B-Movie Cast, talking about Roger Corman flicks like Big Bad Mama and Grand Theft Auto.

Fiona is from Scotland, and Nic hails from Kentucky, so of course they met while teaching English in Japan, before eventually making their home in the Bluegrass State. Fiona’s writing specialties include food and travel (she’s the author of Wicked Lexington) as well as science, and Nic devotes as much time as he can to his passion for vintage horror movies and other cheapie cinematic delights. Which is why he was a natural to join with the late Vince Rotolo in hosting a B-movie podcast that’s been on the air since 2006. (Vince’s wife Mary now joins Nic in capably anchoring new broadcasts.)

Given Nic and Fiona’s varied enthusiasms, it’s no surprise that they have launched a series of B-movie cookbooks. Their first celebrated the Fifties, pairing drive-in favorites like Godzilla and Creature from the Black Lagoon with appropriate recipes. I’ve just finished reading the sequel, which is titled The B-Movie Cookbook: The Sixties. This slim, colorfully illustrated volume features 12 B-movie classics from the decade, everything from The Brain that Wouldn’t Die to Santa Claus Conquers the Martians. Nic engagingly summarizes the plot of each film and adds quirky production details, after which Fiona comes up with simple but enticing recipes guaranteed to make your home film screening complete. Halloween, of course, is one of the Browns’ best-loved holidays, which is why creepy films suitable for October 31 inspire some of their finest efforts. For George Romero’s 1968 Night of the Living Dead, Fiona salutes the Polish community of Pittsburgh, where the film was famously made, with a serious recipe for Pierogies. But she also gets creative in suggesting the blood-and-guts aspect of this zombie classic. Apparently the actors playing the zombies in fact feasted on-screen not on actual human flesh but on a concoction of roast ham and chocolate syrup. Fiona takes mercy on her readers, sharing with them instead a Mexican-inspired recipe for Pulled Pork with Chocolate Mole (delicious but decidedly scary-looking). And for dessert she offers White Chocolate Mousse Brain with Strawberry Sauce. If yours comes out looking like the photos in the book, it will definitely give a shiver to your partygoing friends.

Much space is devoted to Spider Baby, the 1967 creep-fest by Roger Corman alumnus Jack Hill about a family with weird inclinations. That’s partly because Fiona and Nic have located the film’s star, Beverly Washburn, who shares her on-set memories as well as some of her own family taste treats. But I particularly like Fiona’s culinary suggestions for this vastly bizarre film. The book informs us “there is a memorable dining scene in the movie featuring weeds, mushrooms, and an unfortunate cat. Sparing those, we’ve instead opted for some spider novelties and mushroom cookies.” I love the photo of the Spider Leg Breadsticks perched eerily on a bowl of queso dip. And Spider Cupcakes are wonderfully cute. Serve those alongside your White Chocolate Mousse Brain for an unforgettable Halloween treat.

But, hey – why are no Roger Corman movies included by the Browns? I’d love to see recipe suggestions for such Sixties classics as X: The Man With The X-Ray Eyes and The Masque of the Red Death. Perchance there’s a Corman cookbook in the offing?

October 26, 2021

An Autumnal Tribute to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”

Anita Louise as Titania, the Fairy Queen

Anita Louise as Titania, the Fairy Queen

As a long-time theatre buff, I’ve been suffering serious withdrawal symptoms during the pandemic. The few opportunities I’ve had to see actors on stage have been outdoor performances, sometimes awkwardly staged in parking lots. But I did celebrate the end of summer with a Midsummer Night’s Dream in the most magical locale you can imagine. Topanga Canyon’s Theatricum Botanicum was founded in 1973 by the actor Will Geer (Grandpa on TV’s The Waltons). Blacklisted during the McCarthy era, Geer had moved his family to the wilds of Topanga to live off the land. Eventually, their domain became an artist’s colony, and the site of an annual repertory season. The playing area is entirely outdoors, and it’s no wonder that A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a standard annual offering. Ensconced in surprisingly comfortable seats in a beautifully woodsy glen, you truly feel as though you too are in the middle of a vast forest, communing with fairy creatures.

(My pleasure in this particular performance was enhanced by the fact that a neighbor’s son, Steven Taub Gordon, had risen from the ranks of the understudies to play one of show’s quartet of lovers, the charmingly addled Lysander.)

Back when talkies were something new and exciting, Hollywood’s big studios went out of their way to launch prestige projects, including elaborate screen versions of Shakespeare’s best-loved plays. MGM, for instance, staged a 1936 production of Romeo and Juliet, starring members of the studio’s prized acting stable: John Barrymore as Mercutio, Basil Rathbone as Tybalt, Edna May Oliver as Juliet’s nurse. The two young lovers were played by long-in-the-tooth Leslie Howard (age 43) and Norma Shearer (the 34-year-old wife of producer Irving Thalberg). It’s a well-spoken production, but also one that’s stiff and unconvincing in its portrayal of youthful passion.

Up until now I’d never managed to see the Warner Bros. contribution to the Shakespeare derby. A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which had been staged as an early silent film back in 1905, was filmed in 1935 by Austrian stage and screen director Max Reinhardt, who had just fled rising anti-Semitism in Europe. Reinhardt adored spectacle, and the film spends much of its length on musical interludes, featuring woodland creatures (fairies, nymphs, trolls) frolicking in the moonlight to the lush strains of Felix Mendelssohn. Today all those supernatural beings, photographed in shimmering black & white, can get a bit tiresome, with the oodles of fairies (all with long silvery tresses and filmy gowns) seeming not far removed from the stylized routines that made Busby Berkeley famous. Still, Victor Jory (wearing what looks like a crown of twisted twigs) makes a stalwart Oberon, and Anita Louise is a lovely Titania.

Among the mortal lovers, perennial juvenile Dick Powell plays Lysander as a ready-for-anything college boy, in a performance that has always been much scorned, even by Powell himself. Opposite him is the very young Olivia De Havilland, making her screen debut. They and the two additional star-crossed lovers, Ross Alexander and Jean Muir, are pretty silly, in roles that always require a certain amount of silliness.

Naturally, it’s the most earth-bound characters who come out best, particularly James Cagney as Bottom the Weaver and the wide-mouthed Joe E. Brown as Flute, who must don a dress to play opposite Bottom in the world’s wackiest performance of the tragic “Pyramus and Thisbe.” Young Mickey Rooney’s antic Puck sounds like a good idea: he was a small, energetic fifteen-year-old who was talented and ready for anything. But Rooney’s hyperactive performance should only be sampled in small doses. After seeing it, you’ll be ready for a Midsummer Night’s snooze.

October 22, 2021

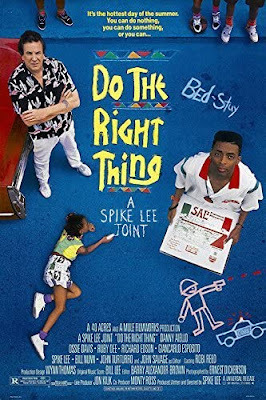

Spike Lee Does the Right Thing

For the past week, I’ve been following the fortunes of my current favorite baseball player, the extraordinary Mookie Betts. It’s all part of rooting for the sometimes infuriating L.A. Dodgers, now locked into a playoff series with the Atlanta Braves. As I write this, the Dodgers have kicked away more than one opportunity to come out on top. But I count on my man Mookie to always DO THE RIGHT THING.

The irony, as I discovered when re-watching Spike Lee’s 1989 breakout film, Do the Right Thing, is that Lee himself plays an important character named Mookie. Like many of the roles played by Lee in his early films, his Mookie is sometimes funny, sometimes lovable, sometimes confused, and sometimes dead wrong. He starts out the film as the gofer and all-around sidekick of Sal (the late Danny Aiello), who owns an Italian pizzeria in a mostly Black Brooklyn neighborhood. The good-hearted Sal, ignoring the rantings of his bigoted son (John Turturro), does his part to be an active member of the Bedford-Stuyvesant community, giving handouts to those who need them and generally making nice. He won’t budge, though, when local toughs demand he add Black faces to the Italian-American Hall of Fame that decorates his restaurant wall. His heroes are Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett, not Dr. King and Malcolm X, and he refuses to make any changes.

On the hottest day of the year, all the locals are steamed up. The young punks are agitating against the pizzeria, where Sal’s angry son is already driving him crazy. The old codgers are bickering among themselves, and the sweet local drunk (Ossie Davis) is being spurned by the tough neighborhood matriarch played by Ruby Dee. Meanwhile Mookie pays a quick visit to his on-and-off girlfriend (Rosie Perez in her screen debut), who’s furious with him for ignoring her and their infant son. The only one staying cool is the local radio DJ, Mister Señor Love Daddy (Samuel L. Jackson, who was then still calling himself Sam). As the sun goes down, the tension rises. Radio Rahim invades the pizzeria with his blasting boom box, and Sal finally snaps. After the police get involved, with tragic consequences, Mookie takes the lead in hurling a trashcan through the pizzeria window.

What’s disturbing about Do the Right Thing is that after more than three decades it still seems so timely, as current as the disturbances surrounding the death of George Floyd. Since 1989 we haven’t gotten any better at answering Rodney King’s plaintive question: “Can’t we all get along?” I give Spike Lee credit for not being a total ideologue. The film shows he can see all sides of an issue, even that of the immigrant Korean grocers so desperately trying to fit into the ‘hood that at one point they try to claim kinship with their Black neighbors. Appropriately the film ends with two on-screen quotations, a hopeful one from Martin Luther King, followed by far more militant words from Malcolm X. But the final dedication to the families of Black victims of police brutality makes clear that when it comes to issues of law enforcement, Lee knows where he stands.

He also knows how to look to far different movies for inspiration. The Lee exhibit at the new Academy Museum reveals where he came up with the film’s opening moments, featuring Rosie Perez in closeup, doing a wildly militant dance to “Fight the Power.” Where’d he get the idea? From Ann-Margret, looming large on the screen, in the first few minutes of a mindless musical from 1963, Bye Bye Birdie. Who would have guessed?

>

October 19, 2021

Death in the Land of Enchantment: Tony Hillerman On Screen

Let’s get this straight: Tony Hillerman (1925-2008) was not a Navajo. Nor did he belong to any of the other Native American tribes that still populate the American Southwest. Oklahoma-born, Hillerman was of German descent, and remained throughout his life a practicing Roman Catholic. But he built his career on eighteen mystery novels featuring Navajo Tribal Police officers Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee. Particularly after his move, as a young journalist, to New Mexico, he became fascinated by the spirituality and the harmony with nature embedded in the traditional Navajo (or Diné) way of life. One of his proudest possessions in later years was a plaque from the Navajo nation naming him among the Special Friends of the Diné, for his skill in respectfully conveying tribal ways to generations of readers, both Native American and not.

My colleague James McGrath Morris is another writer who’s an adoptive son of New Mexican. He’s built his career on biography, and it was no surprise to see him plunge into Hillerman’s life story, which includes an impoverished childhood a serious injury on a World War II battlefield, and a long, happy marriage. I salute Jamie Morris on the publication of Tony Hillerman: A Life, now newly available in stores and the usual online outlets.

Since Hillerman often reached Best Seller status, it’s easy to imagine that Hollywood would have come calling. And it did, via actor/director Robert Redford, who has his own emotional connection to the Southwest and its native people. Redford’s first attempt, backing a 1991 film version of Hillerman’s The Dark Wind, was an unmitigated failure, stemming perhaps from the wrong choice of director (Errol Morris, a famed documentarian, had never made a feature film) and producing partners. Lou Diamond Phillips and other major players were not Native Americans, despite an initial promise that native people be hired to fill out the cast, and Hopi and Navajo tribesmen took offense at how they were portrayed in the film’s story line. Both Redford and Hillerman came out of the experience feeling humiliated.

They tried again in 2002 with a TV movie, Skinwalkers. It featured two Native American leading men, Adam Beach as the young, eager Jimmy Chee and Wes Studi as the more haunted Lt. Joe Leaphorn. Director Chris Eyre had tribal roots as well. The production, aired as part of PBS’s usually Anglo-centric Mystery series, garnered high ratings, and led to two more Leaphorn/Chee dramas, Coyote Waits and A Thief of Time, both released in 2003. The major cast, featuring native women as well as men, remained the same as before, and new tax breaks led to filming in New Mexico, always a vital supporting character in a Hillerman story.

I recently watched A Thief of Time with a mixture of pleasure and annoyance. Some of the acting is weak, and Hillerman’s complicated storyline (which mixes arcane tribal beliefs with some good old-fashioned murder) is hard to follow. But Wes Studi, who first made his mark in Dances with Wolves, is an effectively taciturn Leaphorn, and it’s a delight to see movie veteran Graham Greene, an Oscar nominee from that same 1990 epic, as Slick Nakai, a scalawag evangelist who peddles native antiquities on the side. According to Jamie Morris, Hillerman started out convinced that a novelist had no business trying to interfere with the filming of his book. But he did express objections (to no avail) when his female archaeologist character was turned into a flaming sexpot. Still, the film succeeds in showing us the magnificent New Mexico landscape in all its red-rock glory.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers