Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 42

October 15, 2021

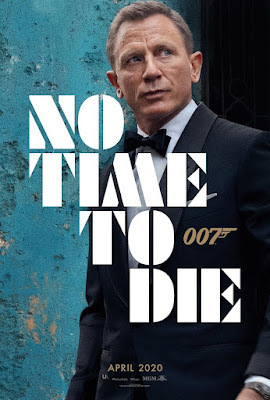

“No Time to Die”: James Bond Shaken and Stirred

James Bond has taught me a valuable life lesson. Back when my generation was discovering Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels (President Kennedy was a fan!), a guy I was dating lent me a paperback copy of Casino Royale. I dutifully started reading it, but wasn’t all that enthralled. Restlessly, I scanned the back cover, which proclaimed, in breathless prose, that the novel was full of exciting moments . . . like Bond romancing a beautiful lady spy. I was puzzled. Though almost through the novel, I’d only seen Bond get horizontal with a nice, wholesome young woman, so where was this female spy? Uh oh! I’d just ruined the novel’s major plot twist. Lesson learned: from that time onward, I’ve never glanced at the promotional copy on a novel’s back cover before diving into the book.

When it comes to Bond movies, I’m hardly the ultimate fan. I enjoyed several early ones; it’s hard not to fall under the spell of the suave, witty Sean Connery. But the various villains with their weird fetishes and bizarre hideaways were too outrageous to be taken seriously. I’m not much on sexy sports cars, nor am I the right gender to fully appreciate the gaggle of Bond Babes, always so intent on shedding their clothing at the slightest provocation. In the post-Connery years, I didn’t watch a single Bond movie, until Daniel Craig came along.

Even more than Sean Connery, Craig is an ambitious actor, active on stage and screen. Looking at his credits, I’ve discovered how often I’ve seen him in a wide range of parts: as an Irish mobster in The Road to Perdition, as English poet Ted Hughes opposite Gwyneth Paltrow as Sylvia Plath, as a Swedish journalist in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, and as a South African who’s part of a Mossad assassination plot in Steven Spielberg’s Munich. He seems to have a fondness for accents, and I suspect he relished every honeysuckle syllable when playing New Orleans detective Benoit Blanc in Knives Out.

Craig reportedly had a great deal of input into his five appearances as Hollywood’s most recent James Bond. Not for him the insouciance of Connery. His Bond is less cocky than mournful, keenly aware of all that has been lost (friends, lovers) on his watch. The script of No Time to Die turns out to be a canny remembrance of things past, at the same time that it pushes his personal story forward.

Though the film certainly contains beautiful and accomplished women, they do not emerge dripping wet out of the ocean, as a bikini-clad Ursula Andress so memorably does in 1962’s Dr. No. In a cheeky reversal, it’s Bond himself we first see rising from the water, and his still buff physique cannot detract from a smidgen of middle-aged flab. (Craig is now 53.) In A Time to Die, the closest we get to a Bond Girl is the scintillating Ana de Armas, who last appeared with Craig as the good-hearted nurse at the center of Knives Out. Here, she’s a kick-ass assassin in a barely-there black evening gown, the movie’s joyful nod to the Bond movies of old. But the sexual side of Bond is most engaged in a poignant, even somber, interaction with Léa Seydoux, returning from an earlier Craig/Bond film, Spectre..

As the latest Bond villain, Rami Malek too is mournful rather than exuberant. I like director Cary Joji Fukunaga’s addition of Japanese Nōh touches, which suit the austere mood. And the scenery is so gorgeous (particularly an Italian hill town) that I’m almost ready to board an airplane.

October 12, 2021

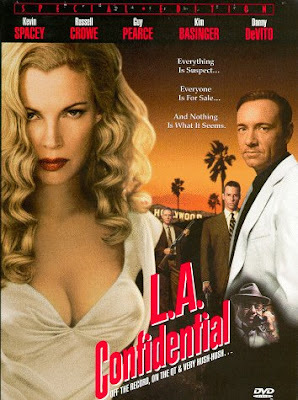

Virginia is for Lovers; Los Angeles is for Filmmakers: “L.A. Confidential” and “L.A. Story”

It’s not exactly “Virginia is for Lovers” or “I ♥ New York,” but a longtime slogan for my hometown has been “L.A.’s the Place.” It’s a catchy reminder that there’s a lot going on here: glamour, intrigue, possibility. And of course movies.

One reason Southern California attracted moviemakers early on was because it could look like many other places. Though today location shooting is the norm, even some quintessential NYC movies were shot in L.A. Like, for instance, Martin Scorsese’s breakout film, Mean Streets. Still, L.A. over the years has sometimes had the chance to play itself. Particularly in the film noir era (1940s-1950s), L.A. sunshine was transmuted into a view of the city emphasizing dark shadows and darker morals.

In the 1990s we saw two major films with L.A. in their titles. One, picking up on the mood (though not the look) of film noir, focused on the City of the Angels as a place of rampant corruption. The other, an outrageous comedy, focused on L.A.’s sexual hedonism before climaxing in a candy-coated embrace.

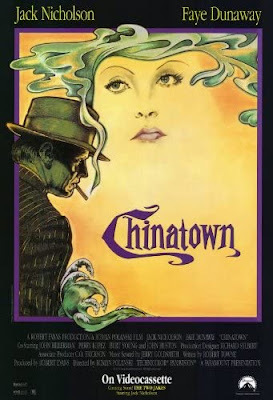

L.A. Confidential (1997) is a worthy follow-up to Roman Polanski’s L.A. masterpiece, Chinatown. Based on a twisty 1990 novel by native son James Elroy, it uses the year 1953 as a springboard to a world where policemen, pimps, and politicians run roughshod over ordinary folks. Perhaps the film’s number-one victim is the lovely Lynn Bracken, who has slipped from showbiz aspirations into the life of a call-girl outfitted (or, in the movie’s parlance, “cut”) to resemble Veronica Lake. Filling out the cast is a cop with a hair-trigger temper (newcomer Russell Crowe), a devious chief of police (James Cromwell), a detective who’s gone Hollywood (Kevin Spacey), and a sleazy gossip columnist (Danny DeVito) who narrates the sordid goings-on “off the record, on the QT, and very hush hush.”

Though much admired in its day, L.A. Confidential didn’t take home the big prizes. Yes, Kim Basinger won a supporting actress Oscar for playing vulnerable but clear-eyed Lynn, and the film was also honored for its adapted screenplay. But this was the year Titanic picked up most of the marbles (11 Oscars), so L.A. Confidential was very much an also-ran. I want to salute the late Curtis Hanson, the film’s director, producer, and co-scriptwriter, for a job very well done. Hanson, who provides thoughtful commentary on the film’s DVD, is yet another Roger Corman alumnus who made good. Debuting as a director with a cheapie Corman thriller, Sweet Kill (1972), Hanson went on to showcase his skills as a maker of genre hits like The Hand that Rocks the Cradle and The River Wild before L.A. Confidential thrust him into the spotlight. Alas, he could never quite repeat the film’s success.

At the start of L.A. Confidential there are quick shots of the city at work and at play in 1953. There we glimpse the grand opening of an L.A. freeway. By 1991, the year of L.A. Story, freeways are a given. So are backyard swimming pools, complicated espresso drinks, the Hard Rock Café, and of course earthquakes. SoCal native Steve Martin and company have fun smirking at Angelenos’ social peculiarities, like driving to a friend’s house instead of simply walking down the block. It’s an uneven film, with some brilliant moments. Two of the best: an opening that parodies the start of Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, with a giant hot dog (and not a statue of Jesus) being transported through the air. And of course Martin blithely roller-skating past the abstract expressionist canvases at the county art museum. (In real life he’s a trustee.)

By the way, my colleague Michael Coate, whose Digital Bits site explores film history, has just posted a nifty tribute to Raiders of the Lost Ark on the occasion of its 40th anniversary. I'm quoted in chapter 10 on Deborah Nadoolman's iconic costume design for the film.

October 8, 2021

Treading Water After Watergate: "Chinatown" and "Shampoo"

Pundit Ronald Brownstein, who has been a White House correspondent for the National Journal and a political analyst for CNN, is best known for writing and talking about Washington power-brokers. But his years of connection with the Los Angeles Times as well as his lifelong passion for pop culture have helped shape his brand-new book. He calls it Rock Me on the Water, after a Jackson Browne ballad that also inspired a powerful Linda Ronstadt version. There’s an important subtitle too—1974: The Year Los Angeles Transformed Movies, Music, Television, and Politics. In Brownstein’s view, there was a brief period of transition in which the high idealism and the political fervor of the late Sixties flowered into something quite wonderful, before movies and TV were taken over by the yen for nostalgia exemplified by Jaws (an updated “monster from the deep” B-movie) and the amiable sitcom, Happy Days.

To my mind, the linking of this cultural shift to the twelve months of a specific year doesn’t entirely work. Still, Brownstein makes his point by way of some fascinating analysis of key media moments. In the realm of television, he pays tribute to the powerful transformation of a nation’s viewing habits through the rise of three essential TV series. The Mary Tyler Moore Show, introduced in 1970, looked like a sitcom, but also placed real people in real (and up-to-date) situations, paying particular attention to a young woman more focused on career than on finding a man. M*A*S*H, which debuted in 1972, obliquely reflected the realities of Vietnam, balancing humor with a sober reflection on the horrors of war. The hugely popular All in the Family, which ran from 1971 to 1979, took on such issues as racism, social inequality, and rape. It was America’s #1 favorite series until replaced in 1974 by Happy Days, with its cheery appreciation for a past that never was.

At the movies, Brownstein cites two key masterworks as indicative of a nation’s mood in the wake of the Nixon era. (Both, as it turns out, hinged on the talents of Robert Towne, a Roger Corman alumnus who went on to write some of the era’s boldest screenplays.) Chinatown was—as Brownstein so wittily puts it—“Watergate with real water,” a story of political and moral corruption set in the L.A. of the past but revealing parallels with the present. Shampoo, spearheaded by writer/producer/star Warren Beatty, is a tale of aimless seduction by a Beverly Hills hairstylist who’s considered “safe” because hairdressers are stereotypically assumed to be gay. George’s romp through the beds of countless women takes place in November 1968, on the eve of Nixon’s election to the U.S. presidency. “It was in this way,” says Brownstein, “that Shampoo represented a bookend to Chinatown. Each film documented the decline in early 1970s America by exposing the corruption and decadence of an earlier era in Los Angeles. One movie is about concealment, the other about display, and yet they reach the same bleak destination.”

Brownstein notes that it was filmmakers born before 1940 who circa 1974 were most insistent on chronicling the rot endemic to the American system. He also spends time on Robert Altman’s Nashville, the brilliant 1975 compendium of life on the country-music circuit, seeing it as one more dour reflection of the Nixon years by a man well along in his career. By contrast, says Brownstein, rising Baby Boomer filmmakers like Steven Spielberg and George Lucas turned away from politics in the 1970s to explore (in films like Jaws and Star Wars) of adventure sagas in all their apolitical excitement.

October 5, 2021

The Academy Museum, Take Two: A Salute to Diversity

Part of the mandate of the new Academy Museum of Motion Pictures is to present to the public the breadth of the film community. It’s a very 21st century mission: to try to overcome past industry biases by focusing with particular intensity on the contributions of filmmakers outside the mainstream. Of course a lot of attention is still being paid to the Hollywood status quo, and I’m sure many moviemakers continue to feel slighted.

Yes, the big boys and the big studio movies are very much in the spotlight. For instance, the fingerprints of Steven Spielberg are everywhere (in the E.T. image, the Indiana Jones video tribute, the Close Encounters clip, and Bruce the shark leering at visitors from over the bank of escalators). But that makes total sense when you think of Spielberg as a major museum donor as well as a favorite of most of today’s movie fans. I’m certain my longtime film industry boss, B-movie maven Roger Corman, was not nearly so generous when it came to opening his wallet. Which may help explain why none of the museum’s galleries is dedicated to the art of making genre movies on a shoestring budget.

That being said, the Academy has gone out of its way to tip its hat toward filmmakers of color. An introductory Stories of Cinema gallery on the 2nd floor is divided into five sections. The first introduces 1941’s legendary Citizen Kane in terms of its origins and production. Right next door is a space dedicated to a very different movie, a small ethnic delight from 2002 called Real Women Have Curves. Starring a young America Ferrera, it’s the tale of an East L.A. teenager grappling with her weight and her Latina identity. Her mother is played by screen veteran Lupe Ontiveros, whose death raised hackles at the 2013 Oscar ceremony when her photo was left out of the annual salute to “those we’ve lost.”

Next to a salute to editor Thelma Schoonmaker is a space devoted to Oscar Micheaux, a pioneering Black filmmaker (1884-1951) who was the first African American to make a feature-length motion picture. Micheaux is credited on about 40 independent productions, all of them featuring Black actors in stories geared to attracting “colored” audiences. His section of the museum backs onto a lively tribute to Bruce Lee, who brought Chinese martial arts traditions onto the world’s screens.

A much longer and more comprehensive treatment is given to the incomparable Spike Lee, one of the most inventive filmmakers at work today. Lee is a life-long collector of movie memorabilia, and his large section boasts posters autographed by many of his movie heroes, foreign and domestic, as well as items reflecting his own body of work. Most interesting to me: film clips showcasing how mainstream movies from the past—everything from The Third Man to Night of the Hunter to Bye, Bye Birdie—have had an impact on his own directorial choices. And there’s the ultra-cool purple and gold suit he wore to honor the late Kobe Bryant while picking up his first Academy Award (for adapted screenplay) at the 2020 Oscar ceremony.

In the all-inclusive spirit of the Academy Museum, I just watched Daughters of the Dust, a 1991 indie by a Black and female auteur, Julie Dash. It’s an inventive tale of the Gullah people, descendants of African slaves, living on an island off the Carolina coast. I admit I couldn’t always follow the complicated family story, but the film is mesmerizing to look at, as well as beautifully acted, and American cinema would be poorer without it.

October 1, 2021

The New Academy Museum: Take One

I’m hardly a movie star, but earlier this week I felt like one, while attending an Opening Night reception to honor donors to L.A..’s new Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. There was a red carpet with photographers galore, a plethora of open bars, and a dramatically lit open-air reception at the top of what local wags are calling the Death Star, the dome-like structure that houses one of the museum’s landmark theatres. This being L.A., the call for “cocktail attire” resulted in a weird mélange of fashion choices: mermaid gowns, muumuus, exposed cleavage, shorts, men in sequined jackets, women wearing combat boots with their cocktail dresses, funky interpretations of ethnic wear, and people straight out of some law office.

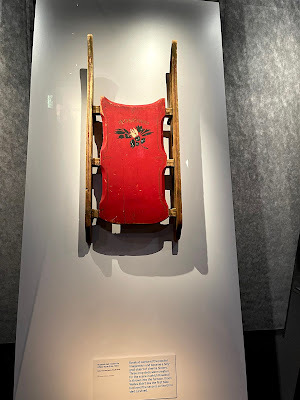

But I’d rather talk about the museum’s contents than the guests’ style choices. Among the priceless attractions on display is Citizen Kane’s Rosebud (reportedly three identical sleds were created, with two burned up for the cameras and one surviving, unscathed). There’s also a primo pair of Dorothy’s ruby slippers, Jeff Bridges’ bathrobe from The Big Lebowski, the typewriter on which Psycho was written, and the barely-there spangled and feathered outfit worn by Cher at the 1986 Academy Awards. Speaking of Oscars, the museum has plenty of them, displayed in glass cases inscribed with the names of their recipients. The vitrine dedicated to Hattie McDaniel is conspicuously empty: though winning an Oscar for playing Mammy in Gone With the Wind, McDaniel (as a person of color) was given a plaque instead of a statuette. If museum visitors crave their own moment of Oscar glory, they can pay to be photographed hoisting the naked gold man while listening to the roar of appreciative crowds.

But the museum is not just about Oscar night. Movie fans of all stripes can find something to intrigue them, like artifacts from the early days of cinema and galleries devoted to such overseas favorites as Hayao Miyazaki and Pedro Almodóvar. (Exhibits will change over time.) Still, I suspect most visitors will be drawn to the third-floor galleries displaying iconic items from futuristic and fantasy films. That’s the Sound of Water aquaman suit right next to Edward Scissorhand’s blades and leathers, with R2-D2, C-3PO, and a spectral head from Alien not far off.

Still, a motion picture museum needs to contain more than static objects. And I’ve realized the exhibits that tickle me most are those using film itself to make a point. There’s a wow of a 26-minute featurette cleverly combining footage of space-travel movies from Méliès’ A Trip to the Moon (1902) to Flash Gordon (beginning in 1936) to Interstellar. In an exhibit detailing how filmmakers enhance the sound recorded on-set, we see a sequence that features Indiana Jones escaping death in Raiders of the Lost Ark. It leads us from step to step, through the addition of Foley (a technician munching an apple to simulate the sound of breaking twigs), sophisticated recordings (the blast-off of a rocket makes a terrific stand-in for the rumble of an earthquake), dynamic music (you can’t beat a John Williams score), and “automatic dialogue replacement” to make sure those witty lines are clearly enunciated. I also loved a small area honoring veteran editor Thelma Schoonmaker: clips from such films as Raging Bull and The Wolf of Wall Street are used to highlight classic editing techniques like the whip pan and the iris shot.

Much more to come, but I’ll close here by mentioning a brilliant combination of the old and the new: a huge zoetrope illustrating the basic principle of film photography by way of Pixar’s Toy Story characters. OMG!

September 28, 2021

Up All Night with “The Card Counter”

Paul Schrader is not exactly a newcomer to Hollywood. The much-admired screenwriter of Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) and Raging Bull (1980) as well as more than 20 other films, he began directing his own dark material early on. Remarkably, Schrader did not collect an Oscar nomination until 2019, when his First Reformed was recognized for its screenplay. First Reformed, featuring a strong performance by Ethan Hawke as a minister facing a crisis of faith, reflects Schrader’s own strict religious upbringing. He was raised in a Dutch Calvinist household that banned movies and most other kinds of secular entertainments. I’ve known friends who’ve broken away from homes in which movies were taboo, but Schrader is possibly unique in having – once he reached adulthood – cast off parental values so completely by making motion pictures his life’s work.

Which doesn’t mean he threw all of his childhood teachings out the window. Schrader is known today as something of a poet of redemption. His central characters are lost and lonely souls who tacitly blame themselves for their fall from grace. It is only after a good deal of suffering and self-sacrifice that they feel ready to rejoin the human race, sometimes in unexpected ways. This may not seem like much fun to watch unfolding on screen, but 2021’s The Card Counter is a great example of how engrossing a Schrader film can be.

The cast of The Card Counter is led by the protean Oscar Isaac, who’s also appearing in 2021’s sci-fi epic, Dune, as well as opposite Jessica Chastain in a new HBO adaptation of Ingmar Bergman’s 1973 Scenes from a Marriage. In the HBO drama, Isaac plays one half a couple, someone who desperately wants his relationship to survive. In The Card Counter, by contrast, he’s a loner, a man committed to solitude. He’s analytical enough to make a comfortable living as an itinerant gambler, haunting card rooms from Vegas to Atlantic City. Within the hurly-burly of up-all-night high-stakes casinos offering drinks, smokes, and sexual come-ons, the man who calls himself William Tell is fundamentally solitary. It’s only gradually, via disturbing flashbacks of time spent stationed at an overseas military prison, that we learn why he shuts others out. We also learn that he’s quietly capable of both love and revenge.

The film does not belong to Isaac alone. Featured players, all impressive, include Tiffany Haddish as a woman who capably runs a stable of gamblers while managing to stave off her own demons. There’s also Tye Sheridan as a baby-faced young fellow who awakens Tell’s compassion, as well as Willem Dafoe (a Schrader regular) as a man from Tell’s past who haunts his dreams until he re-emerges in the everyday world.

I had expected a Schrader script to be well-written, but I wasn’t prepared for the artfulness of his work as a director. Those essential flashbacks are filmed with a wide-angle lens that distorts familiar images and brings home the horror of the moment. And when it comes to character details, Schrader is terrifically inventive. As Tell travels the country, spending nights in anonymous motel rooms, he has the never-explained habit of wrapping every piece of furniture in white bedsheets he carries with him from place to place. When, at last, he confronts Dafoe’s Major John Gordo at his sumptuous DC-area home, I glimpsed something of the same deliberate austerity in Gordo’s surroundings. Why? That’s one of many elements in this film that’s worth pondering. As is, of course, Tell’s fate at the final fadeout, upon which Schrader’s camera dramatically lingers.

September 23, 2021

“Third Man” Out

The Third Man is a tricky little movie, one that’s full of surprises for the unwary. For one thing, the title is deliberately misleading. The identity of that mysterious third man is, in the scheme of things, quite beside the point. And the zither theme that continues throughout the film is so jaunty that you suspect you’re being prepared for a joyous romp. Something Fellini-esque, maybe? (Hardly true, as it turns out.)

Finally, The Third Man is usually considered an Orson Welles tour-de-force. In fact, he didn’t direct (Carol Reed did), though he’s given some kudos for unbilled contributions to the screenplay written by British novelist Graham Greene. And his role in the film, though pivotal, is fairly small in terms of screentime. Still, he makes an indelible impression, and The Third Man’s intensely dramatic stylistics owe much to such Welles masterworks as Citizen Kane and The Stranger.

One thing Welles apparently did contribute: the film’s most famous line. During a key conversation with Joseph Cotten on a Viennese Ferris wheel, he quips sardonically, as only Welles can, “In Italy, for 30 years under the Borgias they had warfare, terror, murder, and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love; they had five hundred years of democracy and peace – and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.” Bingo!

The Third Man, released in 1949, goes beyond the Americana of Citizen Kaine and The Magnificent Ambersons to cast a cold eye on post-Nazi Europe. Its view of a Vienna awash with occupation forces and petty criminals is totally chilling: almost everyone in the cast seems on the take, or suffers from conflicting allegiances Like, for instance, the leading lady (Alida Valli), who in continually switching sides proves herself to be a true femme fatale. And Americans in this world don’t come off any better than their European counterparts. Joseph Cotten’s character, a two-bit novelist visiting from the U.S., is almost terminally naïve. And then there’s the ominous Harry Lime. Today I suspect we’re particularly sensitive to the enormity of Lime’s shenanigans, watering down penicillin for his personal profit, and shrugging off the fact that children are dying – or worse.

The world of The Third Man is that of film noir, international-style. There’s no question it looks fabulous. If the origins of film noir tend to connect with Raymond Chandler’s prematurely seedy L.A., this movie proves that the Old World is even more decadent and down-at-the-heels than the New. Vienna, in The Third Man, is a heady combination of dilapidated grandeur and police state. We see, usually by moonlight, the rococo buildings and twisty streets of the old city, as well as the shadowy depths of its sewers. (The film’s one Oscar went to Robert Kasker for his moody black-&-white cinematography, which take full advantage of location shooting.)

I also commend the filmmakers for their wonderful collection of faces. The bit players in The Third Man are often wonderfully eccentric, even macabre, to look upon. They frequently speak in untranslated German, so that we share with Joseph Cotten a sense of displacement and being the odd man out. The dapper Cotten, one of the original Mercury Players, seemed to specialize in being a foil to Welles: in films like Citizen Kane he was the nice guy who both admired and ultimately couldn’t help resisting Welles’ powerfully physical presence. He plays that role here as well. But let’s not forget Hitchcock’s 1943 Shadow of a Doubt, in which the sinister side of Cotten comes fully into the ligh.

.

September 21, 2021

Making a Ruckus for “Shakespeare Wallah”

What could the word “Wallah” possibly mean? I was once told it’s the kind of nonsense syllable that background extras use to suggest general crowd noise on stage or in a film. It’s also a Hindi suffix implying someone who performs a particular task: thus a chaiwallah might be a young man who serves tea. Both senses of the word seem apt for the 1965 film Shakespeare Wallah, the story of an acting troupe, led by a family of English expats, who tour the sub-continent, bringing Shakespearean productions to Indian audiences.

Shakespeare Wallah is an early film of the celebrated duo Ismail Merchant and James Ivory, in collaborator with screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. Given Merchant’s roots in Indian culture, the team had wanted to explore a touring troupe of Indian performers, seen against the recent political and social changes within the country.. But the discovery of an unpublished diary by an English actor, Geoffrey Kendal, took them in a slightly different direction. Kendal and his family, including wife Laura Liddell and two daughters, had devoted their lives to touring India with the plays of Shakespeare. Ultimately, the Kendals played versions of themselves in Shakespeare Wallah, though the film hardly reflects their precise circumstances. The film’s accent is on the family’s struggles to continue promoting their art in a newly independent country where Shakespeare is less revered than team sports and Bollywood.

Making her film debut is nineteen-year-old Felicity Kendal, playing a version of her older sister. (Kendal has since had a distinguished acting career, including a personal and professional relationship with playwright Tom Stoppard.) In Shakespeare Wallah she is Lizzie, the troupe ingenue, sensitively portraying Ophelia and Juliet. But her love of the stage is shaken by an unexpected romance with an Indian playboy, portrayed by handsome Shashi Kapoor (in real life her sister Jennifer’s longtime husband).

Unfortunately for Lizzie, Kapoor’s character already has a mistress, the Bollywood prima donna Manjula (Merchant-Ivory favorite Madhur Jaffrey). Hers is the role that made the biggest impact on early audiences, leading her to collect the Silver Bear for Best Actress at the Berlin Film Festival. Manjula is a monster, though a wholly entertaining one. Loving public attention, she makes a stir wherever she goes. She’s introduced in an amusing scene wherein she’s filming a Bollywood-style musical number, full of stylized pouts and gestures that couldn’t be more distinct from the classical technique of the Shakespearean troupe. When she’s persuaded to watch the English thespians perform Othello, she makes the moment all about herself, signing autographs and posing for photos in the middle of the climactic scene of Desdemona’s murder. Then, while Othello is still bemoaning his lost love, she makes her exit, only to be swarmed by fans in the theatre lobby. It’s a key indication of how the arts scene is evolving in mid-century India: veneration for English tradition is quickly going out the window.

It’s a shame that the film’s budget was only $80,000, not nearly enough to film in color. India is a land of vivid visuals, and the monochrome palette doesn’t do it justice. Ivory has admitted, “If we had made the film in color, the love scenes in the mist would have looked very strange, as some shots were done with smoke bombs given to us by the Army, which make a bright yellow smoke.” One technical detail fascinates me: the film’s eclectic score was created by none other than Satyajit Ray, the Bengali director of such masterpieces as 1955’s Pather Panchali and the rest of his Apu Trilogy. It doesn’t get much better than that.

September 17, 2021

The Girl-Power of Cinderella

Cinderella, especially the French version by Charles Perrault, might be the most popular fairytale of all time. I think we all respond—especially if we’re female—to the story of a poor girl who rises above adversity to capture the heart of a prince. In the world of Cinderella, it all seems so simple. If you’re both pretty and virtuous, you can escape your dysfunctional family, improve your wardrobe, and live happily ever after.

Walt Disney, of course, became a major Hollywood player in 1937when he released a full-length animated version of another classic tale, Snow White. This Disney heroine was practically unique in that she (in accord with the template introduced by the Brothers Grimm) had dark hair, “as black as night.” But by the time the Disney folks got around to Cinderella in 1950, they had reverted to the familiar image of a light-haired heroine, one who eventually switched from rags to a magical azure gown at the wave of her Fairy Godmother’s wand. This animated Disney Cinderella was a major international hit, one that pulled the Disney company out of its post-war doldrums and provided an visual image (the Cinderella castle) that still serves as the company’s logo.

Naturally, the Disney version tempered the romantic story with comic sidekicks and cute animals, including two talking mice who serve as the heroine’s pals. There was also music; both sappy ballads (“A Dream is a Wish Your Heart Makes”) and lively character songs (“Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo”). But the most appealing musical version of the Cinderella story is probably that which debuted on live television in 1957, with Julie Andrews in the title role and a full score’s worth of classic tunes (“A Lovely Night,” “Do I Love You Because You’re Beautiful,” “In My Own Little Corner”). A black-and-white kinescope is all that survives of this big TV event, but the show was revived with Lesley Ann Warren in 1965. Over thirty years later, it re-emerged in a racially diverse version, starring Brandy, Whitney Houston (as the fairy godmother), Bernadette Peters (as the stepmother), and Whoopi Goldberg (as the queen). In 2013, Broadway finally came calling, and Cinderella was re-launched as a stage show with a brand-new book that emphasized her kindness as well as her beauty. It also gave her a meet-cute with the prince, disguised as a commoner, so that their love would seem more organic and less the result of his exalted status. Everything came full circle with a Kenneth Branagh extravaganza (2015), starring Lily James in long blonde tresses and a gorgeous blue gown.

Leave it to Amazon Studio to launch its own musical Cinderella, which has just appeared on Amazon Prime. It’s written and directed by Kay Cannon of the Pitch Perfect movies, and seems to be directed toward tweens who believe in grrrl-power as well as romance. There’s some funk in the score, and this Cinderella (despite her quasi-medieval surroundings) is looking for a career as well as for love. Lots of dance and music fill the screen, though many of the songs are familiar pop standards. Like the stepmother, explaining why she expects her girls to marry for money, belting out Madonna’s “Material Girl.”

Pop star Camila Cabello is a sassy Ella, and the racially-diverse cast includes Idina Menzel, Pierce Brosnan. Minnie Driver, James Corden (who also produced), and Billy Porter as a thoroughly swishy fairy godperson wearing a fabulous golden coat. Clearly this a production for girls who dream of being loved but also want to run kingdoms and start their own clothing lines. The upshot: Cinderella as the first influencer?

September 14, 2021

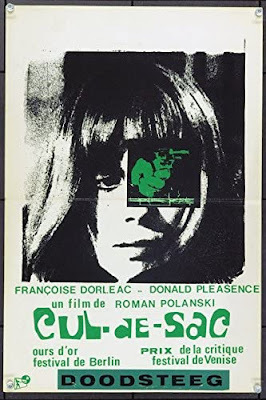

Heading into a Cul-de-Sac

Roman Polanski and the American film industry have had an unusual relationship. Polanski has been a Hollywood hero (for directing such major hits as Rosemary’s Baby and Chinatown), and a Hollywood victim (for losing wife Sharon Tate and their unborn child to the Manson murder ring). In 1977 he evolved into a Hollywood fugitive, the result of a lurid sexual escapade with a thirteen-year-old girl at Jack Nicholson’s Bel-Air home. Though he continues to win acclaim, even in Hollywood, for such deeply moving films as The Pianist (2002), he is still today considered a fugitive from the U.S. justice system. It’s not my place here to either condemn or excuse Polanski’s behavior. Suffice it to say that he’s an extremely talented director, and one whose childhood traumas probably influenced his distinctive taste for the perverse. After all, as a six-year-old Jewish child in Krakow, he witnessed his parents being hustled off to Nazi death camps, then lived for years in foster homes, pretending to be part of the Roman Catholic majority.

Before Polanski arrived in Hollywood, he shot much-acclaimed films both in Poland (Knife in the Water) and the United Kingdom. The psychological horror of Rosemary’s Baby was preceded by Repulsion, a British film starring Catherine Deneuve as a beautiful but sexually stunted young woman obsessed with a fear of men’s desire for her. Repulsion was Polanski’s first film in English. A year later, he made another film he had co-scripted. Called Cul-de-Sac, it was something he once declared was one of his proudest achievements.

Cul-de-Sac is both very simple and very odd. Set in and around a centuries-old castle-like structure on a Northumberland island, it is in some ways a tone-poem that focuses on ancient stones and the lapping of the sea. In this stark setting, we come to know three people. One is a middle-aged man, apparently retired from a successful business career, who has retreated to this castle to paint, raise chickens, and enjoy the good life. He’s played by Donald Pleasence, the bald-headed British actor often cast in sinister roles. (See, for instance, his portrayal of a villain in a James Bond flick, You Only Live Twice; he also played the psychiatrist in Halloween) Here he’s not sinister so much as weak, a man physically and emotionally incapable of defending hearth and home. That home includes his second wife, the young and beautiful Françoise Dorl ac (Deneuve’s sister in real life), who seems to like stripping off her clothing in the presence of other men. This oddly-coupled pair hardly expects the arrival of a two-bit gangster hiding out after a botched robbery. He’s played by Lionel Stander, a refugee from Hollywood in the blacklist era, after years of playing sidekicks in films like Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and A Star is Born. Stander was a big man, broad of shoulder and deep of chest, whose trademark was a distinctively gravelly speaking voice. In his presence the diminutive Pleasence shrinks to nothing, and the interplay of the trio (punctuated when a few more unexpected guests turn up) is sometimes funny but always ominous.

Cul-de-Sac, which won top prize at the Berlin Film Festival, will not be to everyone’s taste. Though one trailer I saw promised that it would be “fun” for moviegoers, I doubt that most Americans looking for a good time at the cineplex would find this their cup of tea. It reflects the era’s nihilistic sense of alienation, as seen in the work of playwrights like Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter. But if you like the macabre, this one’s for you.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers