Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 38

February 24, 2022

Parallel Stories in “Parallel Mothers”

What makes a Pedro Almadóvar film so exciting is that, while watching it, you don’t always know where it’s going. Not for him the tidy formulaic structure (set-up, complication, climax, resolution) prescribed by screenwriting gurus. Instead, he deals in juxtapositions and surprises. But the biggest surprise generally comes at the end, where you suddenly realize what his intentions have been all along.

His latest, Parallel Mothers (Madres paralelas), is succinctly described as “the story of two mothers who give birth the same day.” This focus on mothers and babies is accurate, as far as it goes. It also puts this film in line with others in which Almadóvar focuses his gaze almost exclusively on the female of the species. It’s hard to think of other male directors who’ve devoted themselves so intensely to exploring the lives of women, in all their complexity and beauty. See for instance All About My Mother (in which a trans woman is part of the cast of characters) and Volver. Both of these films feature an Almadóvar favorite, the luminous Penélope Cruz, who stars in Parallel Mothers as the mother of a newborn. For her vibrant performance as Janis (named after Janis Joplin by her hippie mom), she was recently nominated for a Best Actress Oscar.

It's curious, come to think of it, that motherhood looms large in this year’s Best Actress category. In Being the Ricardos, Nicole Kidman plays Lucille Ball as the mother of a young child, one who is dealing with a second pregnancy while her career and her marriage hang in the balance. (Alas, none of the material pertaining to the new pregnancy, is either accurate or convincing.) In Spencer, Kristen Stewart as Princess Diana survives a holiday weekend from hell partly because her young sons are nearby. Olivia Colman in The Lost Daughter can’t get past her own parental failures of many years before. By contrast, Cruz plays a new mom, older than most, who throws herself joyfully into the obligations and delights of tending an unplanned baby. It’s only several very unexpected twists of fate that turn her world upside down, leading her into a moral dilemma she (and we) didn’t see coming.

But this is not only a film about motherhood. It’s also, though more subtly, about being a daughter: both Janis and the very young roommate with whom she bonds at the maternity hospital have reason to feel cheated out of a mother’s embraces. And there’s another key strand, one that begins the drama, then seems to disappear, before re-emerging powerfully at the end. The film kicks off with Janis persuading a noted forensic anthropologist to take an interest in her home village, where a clutch of husbands and fathers were massacred by Fascists, then dumped into an unmarked grave. The women of the village are desperate, after more than a half-century, to reclaim the bodies of their loved ones and given them a proper burial. Thanks to the efforts of Janis, the work is begun. Which leads to a conclusion that not only underscores what Franco’s goons has done to the people of today’s Spain but also drives home the underlying motif through which Almadóvar binds disparate plot strands together. It’s a matter of family ties, of inheritance passed on from the old to the young, of the moral values as well as the genetic materials that connect generations. Strong stuff, this. The solemn but joyous uniting of all the film’s major characters in the film’s final scene suggests that Almadóvar, for all the gloom of his story’s details, is able to look forward with hope.

February 22, 2022

Oh, O'Henry!

They don’t make ‘em like that anymore: compilation films based on sentimental stories from a single author. But in 1952, Twentieth-Century Fox assembled its most experienced directors and its brightest box-office stars to bring to the screen five stories by O’Henry, he of the famous twist endings. To give their film added cachet, Fox creatives chose as their narrator the great American novelist, John Steinbeck. Backed by a book-lined study, Steinbeck—in his sonorous baritone—praises William Sydney Porter’s literary skills, the ones that made his literary alter ego famous throughout the world, and sets the scene for each tale. The whole mishmash is given its own title: O’Henry’s Full House.

Needless to say, the stories are a mixed bag, depending on the varied contributions of writers, directors, and actors. Henry Koster may not have the best track record of the directors represented here, but since his “The Cop and the Anthem” stars the great Charles Laughton at his finest, the opening segment is definitely the best. Laughton plays Soapy, a jovial n’er-do-well with no visible means of support. His usual M.O., when the city is too cold for sleeping on park benches, is to break a few laws and then enjoy three months in a comfortable jail cell. Only problem: though he steals an umbrella, throws a brick through a store window, and eats a sumptuous meal for which he has no money to pay, he can’t manage to get himself arrested. When he is at his lowest ebb, clutching at the hope of a better life . . . that’s when O’Henry’s brand of irony kicks in. (I’ve got to mention a small but memorable role by Marilyn Monroe, whose short scene with Laughton has a poignance that’s truly impressive.)

“The Clarion Call,” about a crime reporter who meets up with a childhood-friend-turned-criminal, is most interesting for the outsized performance of Richard Widmark. As the maniacal crook with the outsized laugh, Widmark was borrowing from his own Oscar-nominated performance in 1947’s noir classic, Kiss of Death, also directed by Henry Hathaway. I’m told that Widmark’s inspiration for both roles came from his love of the Joker character in Batman comics. And his portrayal, in turn, influenced Frank Gorshin’s Riddler and other screen Batman villains.

O’Henry had a special sympathy for the joys and (particularly) the woes of common folk, especially those who led joyless lives in city tenements. “The Last Leaf” is a prime example of the author at his most sentimental. It’s the story of a young woman (Jean Peters) jilted by her wealthy lover, who returns to her humble flat and succumbs to pneumonia. Winter is coming on: as her sister (Anne Baxter) worries over her, she becomes obsessed with the idea that she’ll die when the last leaf falls from the vine she can see from her window. Gregory Ratoff plays a down-at-the-heels old artist who wants to help her regain her will to live.

Two of O’Henry’s most famous stories come last. Writer Ben Hecht and director Howard Hawks were involved with the comic tale of “The Ransom of Red Chief,” with Fred Allen and Oscar Levant as two inept conmen who plan to kidnap a local boy and hold him for ransom. As a pop culture fan in the Fifties might have said, “Taint funny, McGee.”

The schmaltz reaches its peak with “The Gift of the Magi,” in which Jeanne Crain and Farley Granger—impoverished young marrieds—sell their most prized possessions to buy one another the Christmas gifts of their dreams. We end with Christmas carols and happily-ever-after. Aw shucks!

Dedicated to Jack Neworth, fellow Laughton admirer, for introducing me to this obscure title.

February 18, 2022

By Way of Obit; Yvette Mimieux and Some Others

The recent death of Yvette Mimieux, once the radiant young blonde star of Sixties movies, has sent me back into my own past. I remember her as beautiful and vulnerable in such hit teen movies as Where the Boys Are. I forgive her for kinky tripe like Three in the Attic, and acknowledge that she somehow kept her dignity in a low-budget Roger Corman crime thriller, Jackson County Jail. Her passing led me to watch her screen performance in perhaps her most ambitious role, in 1962’s Light in the Piazza.

I’ve wondered about Light in the Piazza since I saw the Los Angeles production of the award-winning 2005 Broadway musical version. Though critics cheered, I found the play’s plot logic deeply troubling. The central characters are a mother and her young adult daughter, wealthy Americans leisurely enjoying Italy. To the mother’s dismay, the daughter quickly falls for a handsome young Italian, and he for her. As a wedding is being discussed, we discover a melodramatic complication: Clara once sustained a serious head injury, and she’s mentally and emotionally stunted. Her mother faces a serious dilemma: stop the wedding, or allow her daughter to find a happiness that may be temporary. It all seemed like hooey to me, and I was never convinced that the Clara I saw on stage had the emotional age of a ten-year-old.

That’s why, in homage to Mimieux, I watched the film, which stars Olivia de Havilland as a deeply troubled mother. It’s a bit sappy, though Florence and Rome look lovely. The time given to the strain of the relationship between de Havilland’s Meg and her no-nonsense husband (Barry Sullivan) helps explain the puzzling turnabout in Meg’s attitude toward the young lovers. And I saw something in Mimieux’s performance that confirms who Clara is—someone who, for all her charm, will never progress beyond being innocent and girlish. A belated brava to Mimieux.

Somehow I’ve never had a moment to salute Betty White upon her passing at the age of almost-but-not-quite 100. It’s sad to lose her, but how wonderful that she enjoyed a long, long career, and a life that was happy and productive right up to the end. Some of those we’ve lost recently started out in showbiz at a much younger age than Betty White, but discovered what a mixed blessing child stardom can be. I grew up watching Tommy Kirk in a whole string of Disney hits, like Old Yeller and The Shaggy Dog. He later was a perennial in a series of teen beach movies in the Sixties. Who knew then that his parting from Disney had been abrupt and painful, caused at least in part by the homosexuality he couldn’t hide? Along the way he picked up a drug habit, and at one point (despite his substantial childhood earnings) was nearly broke. Somehow he got through all that, living out his days quietly, far from Hollywood.

It was just last month that we lost Peter Robbins, not a household name but a voice to be reckoned with. From 9 to 16, he was the original voice of Peanuts’ Charlie Brown on a number of major TV specials. Eventually mental illness kicked in; at age 65 he died by suicide.

Jane Powell, star of Golden Age musicals like Seven Brides for Seven Brothers started in the business at age 14. Unable to go to college because she was her alcoholic mother’s sole support, she continued performing, and married 5 times. Her last and most successful marriage was to Dickie Moore, who like her understood what child stardom was all about.

February 15, 2022

The Pride of King Richard the Lion-Hearted

L.A. Times film critic Justin Chang recently wrote that King Richard, the biographical film detailing how a Compton security guard named Richard Williams jumpstarted the tennis careers of daughters Venus and Serena, was a “shrewd, slick and enormously satisfying drama.” I generally agree with Chang, but not this time. Shrewd and slick the film certainly is. But for me it was hardly entirely satisfying. At its center is an outsized portrait of Richard, who (to quote Chang again) is “played by an outstanding, wholly committed, sometimes fearlessly insufferable Will Smith,” It’s the contradictions of Richard’s behavior—his obvious adoration of his daughters, coupled with a hard-headed determination to control them and everyone else around him—that makes things interesting. But in tracing the rise of the two Williams sisters on the tennis courts of the world, King Richard raises several questions it never begins to answer.

As soon as King Richardended in young Venus’s tennis triumph, I turned to the Internet to learn more about Richard Williams, trying to understand the family dynamics. The film makes much of the fact that there are FIVE daughters in the household, not just two. They are all lively and playful young women, deeply connected to one another, which made me wonder why it is only Venus and Serena who are being drilled day and night in tennis fundamentals. One of the sisters, Yetunde, is clearly the eldest of the group, involved with academics and on the brink of her own independent life. (She was tragically murdered in 2003, in a case that made national headlines, though this in no way features into the story being told on-screen.) But the two other sisters are apparently young kids, with the two future tennis stars in the middle of the pack. Why would Richard ignore the youngsters when it comes to his plans for success? Wouldn’t these younger girls feel left out?

On the ‘net I discovered that the screen story departs from truth in some key ways. Richard Williams married wife Oracene (effectively played on screen by Aunjanue Ellis) in 1980, when she was a widow with three daughters. Their offspring Venus and Serena were born in 1980 and 1981. Which means they were the youngest children in the household, and the only two related to Richard by blood. How did his obsessive attention to them and their future success affect the other girls at home? Weren’t there any hard feelings? This is one of many matters which the film chooses not to explore.

I realize, of course, that a film is not the same thing as a scholarly biography. Movies need to appeal to a general public, and they need to be short enough to be absorbed at one sitting. But this one left me with so many questions that I couldn’t shake off. Was Richard Williams still alive? If so, what did he think of his big-screen portrayal? And how did his daughters and step-daughters truly feel about him? The fact that Venus and Serena, along with one of their surviving sisters, are listed as executive producers here (and have clearly approved the intimate Williams family photos shown at the end) hints that they’re happy with this largely upbeat look at their complicated dad. In one respect, though, we do see on-screen hints of trouble yet to come. Oracene Williams, though largely supportive of her husband’s goals, is climactically shown standing up to his autocratic ways. The couple divorced in 2002, a fact that is not revealed in the film’s ending crawl but is—to the sensitive viewer—not a total surprise.

February 10, 2022

Dreaming of Last Night in Soho

It’s clear that Edgar Wright has genre films in his blood. He first gained attention with the zombie comedy Shaun of the Dead (I admit I haven’t seen it, but you’ve got to love that title). Since then he’s worked with much bigger budgets on movies I’ve enjoyed, including the screen version of a wacky graphic novel (Scott Pilgrim vs. the World) and a slam-bang car-crash movie (Baby Driver). I just saw his latest, Last Night in Soho, and couldn’t help thinking of it as a Roger Corman release, though without the T&A. In my book, the Corman comparison is far from an insult. Last Night in Soho was doubtless much costlier than the Corman flicks of my era, and it has a far more polished look, not to mention the appearance of such classic British actors as Rita Tushingham, Terrence Stamp, and the late Diana Rigg in key roles. But like Corman movies of the Stripped to Kill variety, Last Night in Soho has wild audacity and just enough kinkiness to make it mesmerizing.

The classier comparison, I admit, would be to Roman Polanski’s Repulsion. Like that memorable psychological horror film from 1965, Last Night in Soho exists largely in the head of a deeply troubled young woman. Eloise (Thomasin McKenzie of Jojo Rabbit) leaves her loving grannie behind in Cornwall to attend a prestigious fashion institute located in a seedy part of London. Her mother had died tragically many years before, but now Ellie is filled with joy—at least at first—at the thought of making her way as a fashion designer. It’s not long, though, before she’s having disorienting visions of nighttime London in the Swinging Sixties. In these visions she herself, in all her country mousiness, seems to merge with a glamorous young nightclub singer named Sandie (Anya Taylor-Joy), a captivating vision in flowing hot-pink minidress and bouffant blonde hair.

Things get stranger and stranger as the two young women’s identities continue to intertwine. (The film’s brilliant cinematography, which makes elaborate use of reflective surfaces, establishes that the one character is literally the mirror image of the other.) Eventually, as the viewer scrambles to figure out the identity of the mysterious Sandie, it becomes clear that there will be blood. More than that I’d rather not say, except to note that an unexpected story twist is in the offing. You might call it cheesy, but in dramatic terms it strikes me as highly effective. Not everyone agrees, though: I note that something called the Women Film Critics Circle voted Wright into its Hall of Shame for a third-act plot element they feel is demeaning to women.

It's time to tip my imaginary hat to the movie’s cinematographer. Chung-hoon Chung. He is used regularly by a giant of Korean cinema, Park Chan-wook, in such masterworks as The Handmaiden, and I hope we’ll soon see more of his dazzling visuals in English-language films. Thanks to his accomplishments, the film critic of the Los Angeles Times calls Last Night in Soho “without a doubt, the best-looking film of Wright’s career.” There are also some admirable performances, led by the two young female leads. The brunette McKenzie, with her big blue eyes, is the very picture of youthful innocence, and it’s jarring to see her evolve (via a dye job and a new hairdo) into an aspiring Sixties go-go girl. As for Taylor-Joy, who first sprang into my consciousness via TV’s The Queen’s Gambit, she seems capable of any dramatic task that’s set for her however outrageous it might be. The same goes, of course, for Edgar Wright.

February 8, 2022

Who is Amos Otis, And Why Are They Saying Those Terrible Things About Him?

So who is Amos Otis? This turns out to be a question that a new indie doesn’t exactly answer. But writer/director/producer Greg Newberry shows the courage of his convictions in transferring his 2019 stage play to the screen. The Cincinnati-based Newberry, deeply concerned about the 2016 presidential election and its implications for the future of his country, crafted a courtroom drama in which a mysterious man stands trial for the murder of an unnamed U.S. president. The advertising copy asks: Who is Amos Otis? Presidential Assassin or Democracy’s Savior?

Newberry’s play, which he says “wrote itself in a matter of weeks,” was staged locally, to much acclaim. It’ss been compared by admirers to eerie futuristic dramas like The Twilight Zone and Black Mirror, and was even under consideration for a Pulitzer Prize. But the goal all along was to bag a bigger audience by making the play into a low-budget but high-quality film. That happened in 2020, with cast and crew facing a pandemic along with the usual financial challenges of any non-studio production. The Amos Otistrailer was completed on January 4, 2021, a mere two days before the attack on the U.S. Capitol seemed to bear out some of the film’s more dire predictions.

From the start, Who Is Amos Otis? is clearly in good hands. Though cast and crew are in many cases new to film, they fulfill their roles with admirable professionalism. The opening draws us in with beautiful midwestern foliage on the screen, a haunting lullaby on the soundtrack. There’s a mysterious moment in which an average-looking guy gets out of a pickup truck and releases dozens of rubber balls into the wild. What’s he up to? That question is soon answered, pulling us straight into a world that is dark and uncomfortable, especially—I’d guess—for viewers whose political views don’t match the filmmaker’s own.

As in the play, the bulk of the film takes place in a courtroom, where the accused assassin, his hard-pressed public defender, and a sneering defense attorney all have their say at some length. An admirably composed judge presides over what promises to be a media circus: only the nearly empty courtroom reminds us that budgets were low and COVID prevented much in the way of angry crowds, flocks of journalists, and close-up action. The cast, led by stage actor Josh Katawick in the central role, plays even the script’s unlikely moments with conviction, and there are sufficient twists to keep us riveted for quite a while.

It's no surprise, though, that after we spend some time in such close quarters, the story’s allure starts to fade. The film, at one hour and 43 minutes, is not unusually long, but there comes a point when we crave some relief from all that speechifying. More and more issues seem to be pulled into the mix (like the whole matter of Lee Harvey Oswald), and the cantankerous prosecutor’s sparring with the judge is repetitious, at best.

Still, Who is Amos Otis? gave me a lot to chew on. It’s heartening to see good actors like Rico Reid (the defense attorney) and Derek Snow (the judge) graduate from miniscule parts into meaty ones, and I deeply admire the let’s-put-on-a-show gumption that turned one man’s political outrage into a complex drama. This film may make some folks of a different political stripe mighty angry. I believe Greg Newberry is in fact counting on that. Outrage is one of the things that the arts are for, right? A big thank-you to Newberry for trying so hard to shake us out of our complacency.

February 4, 2022

Taking a Bite Out of “Licorice Pizza”

In the course of Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth, it takes a brisk one hour and forty-five minutes for a Scottish general to be goaded into murder, be crowned king, lose his wife and his wits, and finally die dramatically in a bloody duel. Paul Thomas Anderson’s Licorice Pizza requires 30 minutes longer for two ambitious but misdirected Valley kids to discover they’re in love. I by no means disdain stories on trivial subjects: films that take a close-up look at intimate relationships are some of my favorites. (See, for one classic example, Paddy Chayefsky and Delbert Mann’s unforgettable Marty.) But though Licorice Pizza has two fascinating central characters, as well as a dead-on look at the San Fernando Valley circa 1973, its meandering structure gives its story little sense of urgency. By the end I was stealing glances at my watch, wondering when this saga would finally grind toward its conclusion.

Licorice Pizza (named after a now-defunct Southern California record shop chain) follows fifteen-year-old Gary Valentine--a self-promoter who is by turns an actor, a waterbed salesman, a pinball magnate, and an all-around hustler—in his conquest of an “older woman,” the elusive Alana Kane. She by turns ignores Gary, teases Gary, works for Gary, rescues Gary, and finally acknowledges that theirs is a bond that can’t be broken. The two are played by cinema newcomers who share distinctive heritage: he’s the son of the late Philip Seymour Hoffman, and she is part of a trio of singing Haims whom Anderson previously directed in a series of music videos. (The entire Haim family appears on-screen in one dinner scene.) Both are complex and quirky, and I fully appreciate the fact that they appear au naturel, zits and all.

Otherwise, what plot the film has is stuffed full of in-jokes, many related to the movie industry. John Michael Higgins plays an obnoxious restaurant entrepreneur with serial Japanese wives. I don’t know exactly what he represents in terms of Hollywood movie culture, but there’s no question that Sean Penn’s Jack Holden is a caricatured view of the ageing William Holden, hitting on girls young enough to be his granddaughters. The male lead character, Gary Valentine, is apparently based on a successful Hollywood type, Gary Goetzman, who went from being a child actor (and waterbed salesman) to a major career as a producer of hit films and television shows. And Bradley Cooper’s Jon Peters, who makes the mistake of buying one of Gary’s waterbeds for himself and main squeeze Barbra Streisand, is vividly portrayed as a larger-than-life blowhard chock full of his own sense of entitlement.

For me the film’s biggest surprise comes when the script dips into the world of local politics, portraying Alana as a devoted volunteer for Valley councilman Joel Wachs in his bid to be mayor of Los Angeles. As someone who remembers the glory days of the real Wachs (he’s played here by Uncut Gems director Benny Safdie), I was surprised to see him portrayed on screen, with particular attention paid to his character flaws and his covert homosexuality. Wachs’ story is a potentially provocative one, but much less so if you don’t have a long memory of his political heyday. For those who could care less about decades-old mayoral contests in Southern California, what is this naming of real names supposed to prove?

If you strip away the cameos, Licorice Pizza is an eccentric version of the classic formula: boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl. It has its charming moments, but I’m still not sure why Hollywood critics are hopelessly devoted.

February 1, 2022

Doing a Number on “1776”

Today if I mention a musical set in colonial America and reflecting the lives of the Founding Fathers, you’ll naturally think of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s magnum opus, Hamilton. That show, of course, has earned raves (and raised some hackles) for casting performers of color in the central roles, thus playing up the revolutionary side of the fight for a new republic, while also reminding us that (unlike the Dead White Men depicted in our high school history books) the founders were complex figures with complex, often-clashing views on race and everything else.

But back in 1969, there was another hit Broadway musical about the Founding Fathers, one in which the Dead White Men of the history books were played by white men who were very much alive. The show won four Tony Awards, including Best Musical, for depicting in some detail a key moment in American history. Almost the entirety of 1776 plays out in and around Independence Hall, Philadelphia, where delegates from the 13 colonies are hotly debating declaring independence from Britain. Among the show’s unusual aspects: in the entire cast there are only two female roles (Abigail Adams and Martha Jefferson – no Sally Hemings here). And there’s a thirty-minute stretch in the first act, as the delegates bicker over policies and procedures, without any musical numbers at all.

Elsewhere there are songs aplenty, everything from a rollicking frontier ballad sung by a Virginian proud of his ancestry (“The Lees of Virginia”) to a stark lament about a young soldier lost on the field of battle. A delegate who after long months stuck in Philadelphia is deeply missing his beloved wife sings long-distance duets with her. But there are also ricky-tick comic ditties in which delegates insult one another, particularly heaping scorn on the much-disliked John Adams.

I don’t know how all this played out on stage. But in 1972, ramping up for the nation’s bicentennial year, Jack Warner brought the stage production to the screen, keeping intact most of the original cast. This meant moviegoers got to see as the “obnoxious, unpopular” though ultimately right-thinking John Adams an actor named William Daniels, best remembered as Benjamin Braddock’s jolly but domineering dad in The Graduate. His is the leading role, though I got much more enjoyment from Howard Da Silva as a sly and colorful Benjamin Franklin, Adam’s frequent (though frequently napping) sidekick.

Scholars agree that the story played out in 1776 takes some liberties with what actually happened. They insist, though, that it remains true to the gist of the basic arguments for and against declaring independence from the Motherland. Of course, the original delegates were not apt to burst into song, nor to participate in quaint little dance routines. This may have worked well on the stage, where we expect a certain level of artificiality. The show’s creators felt their story was enlivened by music, and that songs served to humanize those historical figures who too often strike us as colorless, even stodgy. On screen, however, it’s jarring to watch Founding Fathers musically insulting each other. There’s a music-hall-style number in which Adams, Franklin, Jefferson, and some others—all trying to get out of writing the Declaration of Independence—toss back and forth the quill pen that is meant to be used on the document. This silly, obvious piffle is mirrored by a later (supposedly) comic number in which delegates hotly debate whether the national bird should be a turkey, an eagle, or a dove. (Adams wins on that one.)

Verdict: fascinating material (including a tough debate on slavery) marred by trivializing musical turns.

January 28, 2022

A Tale of Sound and Fury: The Tragedy of Macbeth

The Tragedy of Macbeth, Joel Coen’s first filmmaking venture apart from brother Ethan, owes something to Akira Kurosawa and something to Alfred Hitchcock. Of the many cinematic versions of Shakespeare’s famous tale. Kurosawa’s 1957 Throne of Blood seems the closest match to what Coen has accomplished. The Japanese-language Throne of Blood, freed of the need to grapple with Shakespeare’s challenging but beautiful language, is marked by spare, spooky stylistics. Shot in black & white, it fills the screen with bleak, ominous visuals. The scene of a fog-shrouded “Birnam Wood” slowly creeping toward the new lord’s Spider’s Web Castle is as spectacular as it gets. Calling on Kabuki tradition, Kurosawa alters the familiar tragedy to enhance the bombastic acting style of the classical Japanese stage. But it’s the look of his film that has stayed with me, and clearly with Joel Coen too. (The American Society of Cinematographers has just named this Macbeth one of 5 nominees for this year’s ASC award, along with Dune, Nightmare Alley, Belfast, and The Power of the Dog.)

As for the Hitchcock influence, let’s simply say that in The Tragedy of Macbeth there will be birds.

Visually, Coen strips his Macbeth down to the bare bones: even the unusual aspect-ratio makes for a movie screen—almost square—that hints at long ago and far away. Realism is hardly the point here. Props and set décor are kept to a minimum. Color is bleached out: this is one of several important 2021 films that stick (as Kurosawa did) to stark black & white. Characters wander through nearly empty halls photographed from often-exotic angles.

And what about those characters? Commendably, Coen has chosen to be color-blind in his casting, peopling his landscape with actors of different races. The fact that a Black Macbeth (Denzel Washington) is closely allied with a white Lady Macbeth (Coen’s wife Frances McDormand) is never held up for comment. Though the screen is shared by British and American actors, no attempt is made to unify their speech patterns. For this I have some slight misgivings. Though I’ve never been a fan of old Hollywood’s “mid-Atlantic” accent that makes everyone seem vaguely British (see Price, Vincent), I appreciate the vocal precision that the English actors in this cast bring to their roles. McDormand (who can do no wrong in my book) does a magnificent job of articulating her lines while not departing from basic American speech. Alas, I had a harder time with Washington, who sometimes seemed less comfortable in “speaking the speech” while pulling away from the naturalism he brings to present-day American-based stories.

I wanted to love Washington’s performance, as many critics have. But in the play’s key early moments, I couldn’t quite feel the tug-of-war going on in him between Macbeth’s ambition and his fundamental civility. It was only in the later scenes, wherein the newly crowned king lashes out at anyone who stands in the way, that I felt the full force of his portrayal. McDormand, though, is from the start a forceful Lady McDormand, in love with her husband and his potential for greatness, however he achieves it. There are many fine supporting players, including Brendan Gleeson as King Duncan, Corey Hawkins as a well-spoken Macduff, and Alex Hassell as an enigmatic Ross (whose role is given an extra twist by Coen).

But many kudos have rightly gone to British stage actress Kathryn Hunter, who uses her voice and a highly flexible body to channel all three of the Weird Sisters who accost Macbeth on that heath. Hers is an otherworldly performance just right for this somber, exhilarating tale.

January 25, 2022

The Very Public (Screen) Life of Charles Laughton

I admit it: I���m in love with Charles Laughton. It doesn���t make a lot of sense���for one thing, he���s been dead for sixty years. And despite his long marriage to frequent co-star Elsa Lanchester, I���m not sure how much he liked girls anyway. But in the course of his screen career (1928-1962) he was brilliant in such a wide range of roles that I���ve decided he was one of the best actors on the planet. For good measure, he also tried directing, helming a remarkable 1955 suspense flick called The Night of the Hunter.

My personal obsession with Laughton does not involve such late-career Hollywood blockbusters as Advise and Consent (1962), Spartacus (1960), and 1957���s Witness for the Prosecution (for which he received his third Best Actor Oscar nomination). But I was duly impressed by his drunken bluster as the pater familias in 1954���s Hobson���s Choice, a whale of a man whose selfishness finally sparks a rebellion among his long-suffering daughters. Having seen Laughton play a tyrannical lout, I was not at all prepared for 1935���s Ruggles of Red Gap. In this charming film, directed by screwball-comedy expert Leo McCarey (see Duck Soup and The Awful Truth), Laughton is a Victorian manservant who stays loyal to a caddish English earl until he���s won in a card game by a social-climbing matron from a frontier town in Washington State. Polite, formal, veddy British, and totally self-effacing, Ruggles at first can���t get past his obligations to his new employers. Soon, however, the rough-and-ready locals have confused him with a Civil War hero, and are treating him with the kind of respect he���s never before enjoyed. Suddenly he has a new view of himself and his place in the world. Before long he���s quoting Abraham Lincoln, courting a local widow (Zasu Pitts), and planning to go into business for himself. Hooray for the democratic spirit!

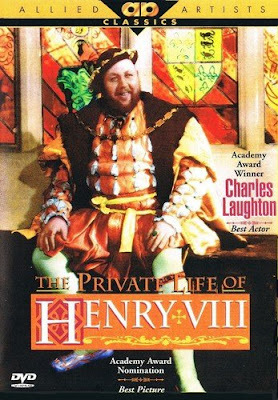

This is hardly the message of the film that won Laughton an Oscar. In 1933, he starred in a lavish British film, directed by Alexander Korda. The Private Life of Henry VIII, a rousing international success, was meant as Britain���s answer to the worldwide clout of the American film industry. The romantic epic, focusing on the ins and outs of Henry���s six marriages, launched major careers for both Korda and Laughton.

This movie���s attitude toward English history is seen from the start, when Henry���s first marriage, to Catherine of Aragon is dismissed in a title card. Catherine was ���a respectable woman,��� we���re told, which is why she never appears onscreen. Instead, the action begins with Anne Boleyn���s execution, on trumped-up charges of adultery, quickly followed by Henry���s marriage to her successor, Jane Seymour. The script rides roughshod over actual historic facts (Henry did not wed Jane on the same day as Anne���s beheading), but takes great pleasure in surveying the gossiping ladies of the court, as well as the common folk who love watching their betters get their heads chopped off in the public square.

Laughton���s Henry is a gluttonous tyrant given to eating with his hands and tossing chicken bones over his shoulder. But he���s not just a man of voracious appetites. Laughton shows us his vanity, his insecurities about his manhood, and his regrets. There���s also a wonderfully comic moment where, muttering ���The things I���ve done for England,��� he shows up to bed new wife #4, the homely German princess played by Elsa Lanchester. To their mutual relief, she���d rather play cards on their wedding night, and happily agrees to a divorce. This may not be genuine history, but it���s great fun.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers