Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 37

April 1, 2022

The Eyes of Tammy Faye Are Upon You

The Eyes of Tammy Faye, the film that just won Jessica Chastain a best-actress Oscar after two previous nominations, opens with a short close-up scene in which a cosmetologist apparently trying to give the televangelist a new look, asks her to wipe away the mascara and lip-liner that have turned her middle-aged face into that of a glamorous gorgon. She wipes—and nothing much happens. It seems most of that makeup is tattooed in place, or as she says, “permanent.” As she emphasizes, coyly, looking straight into the camera, “This is who I am.”

The scene resonates because by the end of the film she’s re-assuring adoring TV audiences that “God loves you, just the way you are.” The irony, of course, is that Tammy Faye Bakker has—throughout the course of this movie—continually undergone physical change. Starting out as a perky but wholesome brunette who meets her future husband at a Bible college, she quickly metamorphoses into a platinum blonde and then a redhead. Her demure bob changes, over the decades, into a flip, then a cascade of curls, then a bouffant coif. God may love her as she is, but she herself has seemed much too restless to be satisfied with her appearance. Is she trying to please God? Her husband? Herself? The movie doesn’t venture a guess, but it’s worth some conjecture on the part of the audience.

There’s one thing about Tammy Faye, though, that remains consistent throughout the film: the basic innocence of her nature. She seems to be someone who truly basks in the glow of God’s love. Not for her the secret cynicism and the overt ethical lapses of her husband, played with smarmy intensity by the ubiquitous Andrew Garfield (so good as a striving young musical theatre guy in tick, tick . . . BOOM!) Much of Tammy Faye’s posthumous legend has evolved out of the gratitude of the gay community because she had embraced AIDS victims in a way that no other evangelical would even consider doing. Chastain—who earned her Oscar because, despite all of her character’s physical permutations, she managed to hold onto the purity of Tammy Faye’s spirit—alluded in her acceptance speech to this all-embracing love.

I was impressed by Chastain’s deeply felt performance, which hardly means that I loved this movie. As I was watching it, the film that came to mind was another flamboyant but true story, that of Patrizia Reggiani, played by Lady Gaga, who plots the murder of her fashion tycoon husband in House of Gucci. Milan’s high-fashion circles would seem to have little in common with the evangelical world generally linked to the American South, but both are over-the-top environments prone to heightened emotions, dark deeds, outrageous clothing, and strained accents. In both films we leap rather breathlessly from place to place and from era to era, seeing how characters evolve from appealing to appalling. At one point Patrizia and Tammy Faye even show up in similar all-white winter outfits, complete with poufy, furry hats. You’d think maybe they were sisters under the skin.

But though I found I had little patience for either film, I cannot equate Tammy Faye with the eager, ambitious Reggiani. Lady Gaga was fun to watch for a while, but her greed was ultimately a turn-off. Not so, Tammy Faye, whose final triumphant scene, belting out “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” in front of a mesmerized Christian audience, seems earned. Despite the clown makeup, I find I have new respect for someone who had always seemed to me the butt of a bad joke.

Posterfor the 2000 documentary, made by two gay filmmakers, that influenced the current film

Posterfor the 2000 documentary, made by two gay filmmakers, that influenced the current filmT

March 29, 2022

The Deaf and the Tone-Deaf: Oscars 2022

As we reached the close of The Power of the Dog, a fellow moviegoer turned to me and said, appreciatively, “Well, I never saw that coming.” By contrast, eventual Oscar Best Picture winner, CODA is, for all of its obvious charm, is a movie about which you’d have to say, “I certainly saw it coming.” Meaning: that happy ending, one that reduced me and everyone else to tears, was tacitly guaranteed from the start. We viewers were rooting for this endearing, if beleaguered, family to move onward and upward, and of course we got our wish. There’s nothing like a feel-good film to lift your spirits and make you think more kindly about your fellow human beings. We need uplift in these terrible times, and CODA gave us what we craved, with both hands.

Which was certainly one reason for its Oscar win on Sunday night. It was also a night that was woefully short on surprises. As for the winners, we certainly saw them coming. Prognosticators have become so acute at ferreting out voting patterns that virtually every award had been correctly predicted in advance. (Suspense? We don’t need no stinkin’ suspense.) It’s partly for that reason, I suspect, that viewership for the ceremony continues to drop. If the biggest unknown of the evening is whether one of those glamorously-low-cut ladies will accidentally tip out of her top on-camera, the event is in big trouble.

Instead of suspense, we got a large dose of identity politics, with virtually every big winner giving a shout-out to some oppressed group. Please don’t get me wrong: Hollywood’s history is full of shameful treatment of groups outside of the mainstream, and I rejoice that films are being recognized for introducing us to cultures and lifestyles that have previously been mocked or overlooked. But I still deeply feel that film awards should be about ART, not simply about the redress of social wrongs. That’s why I personally would not have given a screenwriting award to a film (CODA) that sets up serious challenges for its protagonists—an onerous legal mandate that a hearing person must be aboard the Deaf family’s fishing boat at all times, a sense that the family is isolated from the hearing community without the hearing daughter present to smooth away misunderstandings—and then, after she’s accepted into the college of her dreams, simply sweeps the problems away in a wash of good feelings. This is not to diminish CODA’S power, but only to point out the lapses in its craft.

Of course an Oscar ceremony must work as popular entertainment, not simply as an industry’s recognition of its current leaders. And this one worked hard to amuse the folks at home, shortchanging the winners in various below-the-line categories to have more time for hectic, splashy production numbers (what’s with the chartreuse violins?) and celebrity appearances (what’s with the sports world’s Tony Hawk and Shaun White?) Which brings me to the moment that’s been seized upon by the media. Comic Chris Rock, a presenter, made a silly and apparently pointless crack about the cropped “G.I. Jane” haircut of Will Smith’s wife, Jada Pinkett Smith. Upon hearing this, Smith leaped from his front-row seat and pounced on Rock, in what looked at first to be a planned comedic attack. Then, for us at home, the sound went out.

No joke: Smith was furious at Rock’s mocking reference to his wife’s alopecia. It was a grotesque moment, especially when soon followed by Smith’s tearful acceptance of his Best Actor statuette. Ungainly, sure—but also a welcome distraction from the tried and true.

March 25, 2022

All in the Family: “Big” and “A Few Good Men”

Years ago, when I was a camp counselor, one of the kiddies was Lucas Reiner, youngest child of comedy legend Carl. I confess I kept an eye on little Lucas, waiting for him to say something funny. Lucas has since turned to screenwriting, but it’s his older brother who has gone on to a major Hollywood career. Rob Reiner started as an actor, first in local little theatres and then as Mike Stivic (aka Meathead) on TV’s groundbreaking All in the Family (1971-1979). But it was not long before Rob tried his hand at directing. Starting with the hilarious mockumentary, This is Spinal Tap (1984), he particularly excelled at comedy, helming such classics as The Princess Bride (1987) and When Harry Met Sally . . . (1989).

Gradually, though, Rob Reiner approached less light-hearted material, starting with a grand-guignol-style horror flick, Misery, based on Stephen King’s nightmarish novel. That was 1990; two years later Reiner garnered his only Oscar nomination, as producer (as well as director) of A Few Good Men. It’s a film I finally caught up with on a recent plane flight. Sure, I already knew the movie’s most famous exchange (“I want the truth!” “YOU CAN’T HANDLE THE TRUTH!”), but I wasn’t prepared for how riveting this courtroom thriller proved to be. A Few Good Men has a complicated, dialogue-heavy script (it was Aaron Sorkin’s first screenplay credit), and it deals with the arcane issue of a Code Red among U.S. Marines at Guantanamo Bay. But Reiner keeps things moving, and the film certainly made my hours in the friendly skies fly by.

One of the pleasures of watching movies on a coast-to-coast flight is that you can skip from one genre (or era) to another. I started my flight with a true oldie, Grand Hotel, though in the age of COVID Greta Garbo’s “I want to be alone” certainly sounded anachronistic. Then, following A Few Good Men, I plunged into the most airy of comedies, 1988’s Big, in which a boy of 13 finds himself growing overnight into Tom Hanks. It was only in retrospect that I discovered a connection between these last two films. Big was directed by the late Penny Marshall, who for ten years (1971-1981) was married to Rob Reiner. What a wacky couple they must have made! Marshall revealed her own flair for comedy first as a TV actress (Laverne and Shirley) and then as a director of movies like A League of Their Own. Big, I feel, is her comic masterpiece, energized by her insight into the way kids look at the adult world.

Directors who come from an acting background surely have a special flair for bringing out the best in their performers. Big wouldn’t have worked without Hanks’ antsy, exuberant, very slightly horny performance. I laughed with delight at him trying to shimmy into a pair of much-too-small jeans, and then later (at a fancy cocktail party) having his first encounter with baby corn. The film’s romantic thread, involving a very adult co-worker, avoids being grotesque because of his spot-on childlike innocence.

A Few Good Men too is beautifully cast, starting with Tom Cruise’s cocky but secretly sensitive young Navy attorney and Demi Moore’s conflicted Naval officer. (It’s a mark of the film’s maturity that—though there’s a smoldering subtext between these two—the script never breaks away for the obligatory romance.) Smaller roles are equally well handled, but of course the film’s secret weapon is its villain, Colonel Nathan Jessup, USMC. The cat-who-ate-the-canary part of this smug, haughty martinet fits Jack Nicholson like a glove. Good show!

March 22, 2022

Life is a Masquerade, Old Chum: “The Major and the Minor” and ”Irma la Douce”

My colleague Joe McBride, whose Billy Wilder: Dancing on the Edge has been my recent guide to the full Wilder canon, considers Some Like It Hot a perfect film. He also views this story of two male musicians who escape a vengeful pack of mobsters by disguising themselves as woman as a prime example of Wilder’s fascination with masquerades. So it is, but other Wilder comedies also revolve around characters who transform themselves physically, with unexpected consequences.

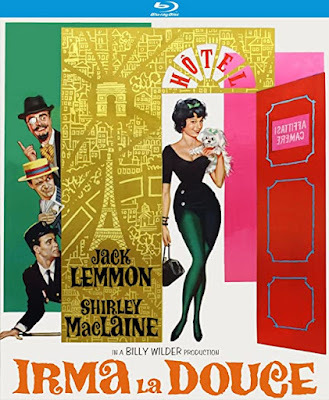

I’m thinking of two films from opposite ends of Wilder’s long Hollywood career. The Major and the Minor, from 1942, was the very first American movie that Wilder directed. Irma la Douce (1963) was a major box-office hit, closely following his back-to-back artistic triumphs, Some Like It Hot and The Apartment (the latter of which earned Wilder three Oscars in a single night).

The Major and the Minor (what a wonderful title!) is a lighter-than-air comedy in which Ginger Rogers—as a young woman sick of trying to find decent work in New York City—decides to return to her Iowa hometown. Trouble is: she hasn’t enough money to pay the full train fare. But kids under 12 can ride for half-price, and so she dives into her suitcase and comes up with an outfit that (almost) makes her look like an innocent kid who’s going to be 12 next week, someone traveling west to visit Grandma. As an adult female in New York City visiting clients as a scalp-massager (!), she has run into her share of old letches. (The prime one is played by Robert Benchley, who tries out on her the famous line about getting out of wet clothes and into a dry martini.) But on the train she’s pursued by two conductors who catch her, in little-girl garb, smoking on the rear platform. Looking for a hiding place, she dashes into the compartment of Ray Milland, an Army major with a warm heart and obviously poor eyesight, who takes pity on the young tyke and insists she spend the night in his unused lower berth. He’s returning to the midwestern military school where he teaches, but his battle-axe fiancée (the general’s daughter) is less charmed than he is by little miss SuSu.

This being a fairy-tale of sorts, our SuSu survives with her spunk intact, unmolested by either a lecherous grown-up or by the teen-aged cadets who are drooling over her charms. When she ultimately unveils herself to the major as an adult woman, he seems happy but not particularly fazed by the turnabout (No one’s perfect, right?), and they’re making plans to marry.

Rogers’ Susan is hardly a prostitute, but her role-playing puts her somewhat in line with Shirley MacLaine’s Irma la Douce, the premiere poule of Les Halles. This candy-colored romance opens with short vignettes in which Irma is seen increasing her take by telling her johns (it’s France, so maybe they’re Jeans?) sob stories that wring from them additional francs. Irma is a terrific liar, but in her way she’s a highly principled young woman, who wouldn’t dream of cheating her mec(or pimp) out of her full earnings. When Jack Lemmon graduates from being a flic(cop) to being a mec, she shows her love for him by insisting she’s obliged to keep working, on his behalf. Which is why he has to put on an act of his own, disguising himself as a lovelorn but antique British lord who lavishes money on Irma but only wants to play double solitaire. As always, amourwins out, and with it Hollywood respectability for all concerned.

March 18, 2022

Hitchcock's "The Wrong Man": Realism versus Drama

Alfred Hitchcock made no secret of the fact that he was fond of stories based on the “wrong man” motif. Most famously he used it in the 1959 comic thriller North by Northwest, in which a bland businessman (Cary Grant, of course) is mistaken for someone else, a man who poses a serious threat to a cadre of evildoers. While desperately insisting he knows nothing about the nefarious plot that’s afoot, he is drugged, chased, shot at, and otherwise harassed by the baddies, right up until the ultimate happy ending. Hitchcock biographers have a field day discussing their subject in terms of his belief that human beings are just one small step away from being implicated for something they haven’t done.

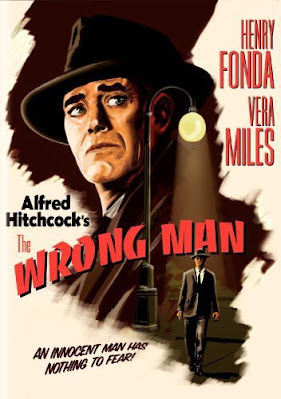

There is in fact a Hitchcock film titled The Wrong Man. It was released in 1956, with Henry Fonda in the central role and Vera Miles as his wife. The expected Hitchcock cameo comes at the film’s very beginning, when the director himself appears in silhouette, explaining that this film is unique in his canon for being closely based on true events. So deliberately does the script follow the actual “wrong man” story of Christopher Emmanuel "Manny" Balestrero that the film is sometimes referred to as a docudrama. The question is: does this adherence to literal truth enhance or detract from Hitchcock’s particular cinematic gifts?

Fonda plays a jazz bass player with a steady gig at Manhattan’s then-famous Stork Club. He’s also a devoted family man who loves his wife and is a hero to his two sons. When his loving spouse reveals she’s going to need expensive dental work, he tries to cash in her life insurance policy, only to be fingered by several office workers convinced he’s the man who has twice robbed them at gunpoint. Poor Manny can’t seem to catch a break: storekeepers all over his Jackson Heights neighborhood identify him as the robber who’s been preying on them, and so he’s dragged off to jail. Meanwhile, of course, the tension within his family accelerates, to the point where wife Rose suffers a serious mental breakdown and needs to be hospitalized. Even when a competent attorney comes to represent Manny, there’s no relief: two of three witnesses who could clear him of the charges against him have died, and the third can’t be found. It’s only when the actual robber is fortuitously caught in the act that his nightmare (sort of) ends.

Well, this was reality for one very unlucky man. Which doesn’t mean that his story holds much excitement for the moviegoer. As Manny’s plight got sadder and sadder, I started checking my watch. Fonda’s acting is highly credible, but watching someone suffer—with no wit, no poetry, no lesson learned—was not necessarily how I wanted to spend my evening. Filmgoers back in 1956 apparently felt the same way about this film, though a few intellectual types like Jean-Luc Godard have since given it high praise.

By way of contrast, Hitchcock shot Saboteur in 1942. This story of an innocent man (Bob Cummings) suspected of bombing the defense plant in which he works plays nicely on the paranoia of the World War II era. His flight from the law drives him from L.A. through the deserts of the Southwest to New York City, where the climax takes place at (and on) the Statue of Liberty. Romance of course creeps into the story. The bad guys are really bad, though it remains unclear exactly what they’re trying to accomplish, and why their ranks include society dowager types. Implausible, sure. But lots of fun.

March 15, 2022

Bright Lights, White Nights: Dancing Through Russia

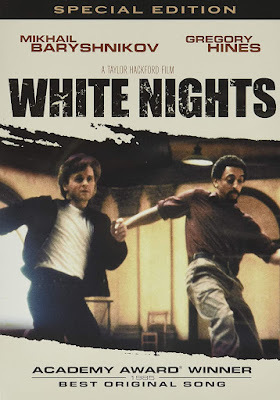

Given Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, I’m not feeling too kindly toward Mother Russia. That’s why I chose to watch White Nights, a Russia-set thriller from 1985, six years before the fall of the Soviet Union. Its title, often associated with a story by Dostoevsky, refers to the few days in summer (at least in northern hemisphere countries near the Arctic Circle) when the sun never sets. That’s the eerie period in which the climax of this movie takes place. But its main attraction is an unusual cast, featuring dance greats Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gregory Hines, along with Helen Mirren and Geraldine Page. In a highly sympathetic key role, Isabella Rossellini made her international film debut, playing a Russian interpreter who has become Hines’ wife.

Today Baryshnikov is, at 74, no longer the svelte young dancer who once set the ballet world ablaze. A treasured member of the Leningrad-based Kirov troupe, he made international headlines by defecting to Canada in 1974, as a way of broadening his artistic horizons. Since living in the west, he has danced in principal roles with American Ballet Theatre, and for nine years was the company’s artistic director. He has also been deeply involved with modern dance, notably with choreographer Twyla Tharpe, whose imprint is strongly felt on White Nights. His first film acting role came in 1977 with The Turning Point, for which he won an Oscar nomination. Much more recently he was featured as a love interest in the last season of Sex and the City.

The biography of Gregory Hines (1946-2003) is less dramatic, but no less impressive. One of the most celebrated tap dancers of all times, Hines also excelled at acting and singing, skills that are featured in White Nights. As an African-American, he doubtless lost out on many career opportunities, but he’s remembered for roles in films like The Cotton Club and Running Scared. His ethnicity plays a major part in White Nights, in which he stars as a Black entertainer who (somewhat like Paul Robeson before him) makes his home in the USSR as a political protest against the nation of his birth. Alas, he finds himself stuck in Siberia, entertaining tiny groups of locals with selections from Porgy and Bess.

Baryshnikov plays Kolya, who—having defected from Russia and the Kirov—quickly becomes a global dance celebrity. En route from New York to Tokyo, his plane makes an emergency landing at a Siberian air base, and the KGB is delighted to have the famous man back on Russian soil. The icy Colonel Chaiko makes him a sweet deal: if he resumes his Kirov career, he gets unimaginable perks. If he refuses, prison awaits. Hines’ Ray Greenwood enters the picture as a minder, assigned to keep an eye on the ballet superstar. Of course the two men, initially at odds, gradually bond over dance and much else.

What makes the film memorable is the amount of spontaneous-looking dance it contains. Both Kolya and Ray reveal their emotions most strongly through dance moves. At the very heart of White Nights is a spectacularly jazzy routine in which the two very different but very talented men find themselves on common ground. But of course a film on this subject needs an action climax, and this one packs a wallop, calling on Baryshnikov’s physicality as well as Rossellini and Hines’ soulful connection. Helen Mirren shines as Kolya’s Russian former partner in dance and romance. And though our glimpses of Leningrad (aka St. Petersburg) are lovely, life in Russia doesn’t seem like something you’d want to experience anytime soon.

March 10, 2022

It’s Not Nice to Fool (With) Mother Nature: “Island of Lost Souls”

Those with long memories may recall a TV commercial for a brand of margarine, featuring a daintily costumed celestial figure who discovers to her surprise that she’s not eating real butter, then snarls, “It’s not nice to fool Mother Nature.” (Cue the lightning strike.) This of course is the subliminal message of the scores of science-fiction and horror films in which a scientist, overloaded with brains and hubris, seeks to move outside the natural order to create something brand-new . . . and inevitably horrible.

Where would Hollywood be without this basic plotline? Certainly I came across it time and time again when working for Roger Corman. One example is 1993’s Carnosaur, which we at Concorde-New Horizons made—fast and cheap—for one very specific reason: to beat Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park into theatres. Jurassic Parkand its sequels are, as all film fans know, modern classics in the upend-the-natural-order genre, setting up a world in which a crazed visionary has installed cloned dinosaurs in a modern-day theme park. (Naturally they escape and run amok.) Our Carnosaur, inventively devised by writer/director Adam Simon, changes things up by introducing a FEMALE mad scientist (Diane Ladd), one who bioengineers a Tyrannosaurus Rex while working on genetically modified chickens. (Or something like that.)

The film in which Roger Corman made his return to directing after nearly twenty years, Frankenstein Unbound (1990) of course draws from one of the world’s most famous mad-scientist stories. Mary Shelley, the very young wife of English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, created the character of Frankenstein as part of an around-the-hearth competition of literary types vying to come up with the best ghost story. Shelley’s novel, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, was published in 1818, when she was 20 years old. Its title character is not the monster, but rather the bright young doctor who assembles a creature out of scavenged body parts, then finds a way to bring it to life. Needless to say, the consequences are horrific—and the movies based on them, starting with James Whale’s (and Boris Karloff’s) Frankenstein in 1931, continue to titillate us today.

Like the Frankenstein films, Island of Lost Souls is based on a nineteenth-century English novel. Its source material is The Island of Dr. Moreau, written by pioneering science-fiction author H.G. Wells, who clearly saw the dangers as well as the promise of scientific research into the origins of man. This story about a crazed vivisectionist, living on a distant Pacific island, who labors to turn wild beasts into humans, has spawned a dozen film versions, starting back in the silent era. In a 1996 movie, Marlon Brando played the mad doctor. But Island of Lost Souls, a pre-code flick from 1932, has the always-mesmerizing Charles Laughton in the role. Naturally, the film is stiff and creaky. But I was particularly fond of the young actress, Kathleen Burke, who is named in the film’s opening credits solely as The Panther Woman. Despite her supposed genetic inheritance from the animal kingdom, she’s a sweet, lovely creature desperate to find human love. Bela Lugosi is also around in a small role, giving the story an additional frisson.

I’ve learned that the subject matter of Island of Lost Souls did not go unchallenged Many national film boards opposed the lines containing Moreau’s boast that he was playing God. Cruelty to animals was a big issue for some, and eventually there were bans in places like Sweden and the UK. If you were a white Australian, you could see the movie unchallenged, but Aboriginals were barred. Today, of course, anything goes.

.

March 8, 2022

Holding Forth on Billy Wilder and “Hold Back the Dawn”

I’ve been on a Billy Wilder kick lately, sparked by reading Joseph McBride’s mammoth 2021 appreciation, Billy Wilder: Dancing on the Edge. McBride, yet another Roger Corman alumnus who’s made good, has been in the course of his long career a screenwriter, a journalist, a critic, and a professor of film. As a biographer of great movie directors he’s endlessly prolific, with a book on the Coen Brothers newly available this month.

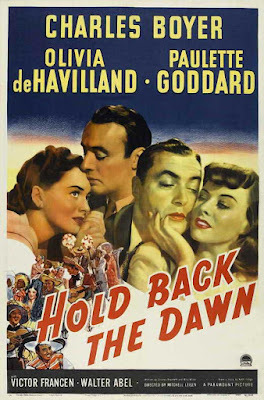

Joe’s writing has whetted my appetite for the more overlooked films in the Wilder canon. Of course I’ve seen such classics as Sunset Boulevard and Some Like It Hot. One Wilder movie not remembered much today is 1941’s Hold Back the Dawn, on which he served as a screenwriter, along with writing partner Charles Brackett, for journeyman director Mitchell Leisen. The well-received film was nominated for six Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Actress. (Leading lady Olivia de Havilland lost out to her sister, and arch-rival, Joan Fontaine, who won for Hitchcock’s Suspicion.) But neither Brackett nor Wilder looked back on this project fondly.

Joe McBride agrees with me that Hold Back the Dawn was partly harmed by a title that seems to promise the wrong things. Before watching the film I jumped to the conclusion that it was an action thriller, maybe a World War II drama with partisans bravely staving off the enemy. It’s definitely war-related, but this is hardly an action film. Instead, it’s a sensitive tale of desperate European immigrants, at the height of the Nazi era, stuck in Mexico while they try to find a way across the border. What makes it particularly fascinating for Joe and for me is that it mirrors in several key ways Wilder’s own story. The leading character in Hold Back the Dawn, played by Charles Boyer, is a Romanian in a Tijuana-like border town, trying to reach the U.S. Back home he was a dancer and, it’s strongly implied, a gigolo. When he comes across his former dance partner, now visiting Mexico as a tourist, she persuades him that the way to gain access to the U.S. is to marry some innocent American dupe, keeping up the deception just long enough to gain legal status. And so he quickly woos and wins de Havilland, a naïve schoolteacher from Azusa, California, who’s south of the border with a broken-down van and a gaggle of noisy schoolkids. Sweetly, though improbably, it turns into a love story.

Wilder would doubtless deny ever being a gigolo, but as a struggling journalist in Berlin he had worked in swanky cafes as an eintänzer (or dancer for hire), charming the ladies who lunched. And he had his own moment of immigrant desperation in Mexico, urgently persuading a member of the American consulate staff to let him cross the border and make his way to Hollywood. McBride posits that Wilder’s take on life was permanently stamped by the era in which he fled Nazi Germany, where his Jewish roots were about to deprive him of a flourishing film career. He quickly found success in movieland, but was never able to rescue his mother and other family members ultimately lost to the Holocaust. Such life experiences naturally helped shape an acerbic outlook that many have called cynical, at the same time that his films reveal a subtle romantic streak. It was Leisen’s cutting of a scripted moment in Hold Back the Dawn—the so-called “cockroach scene” in which Boyer’s character expresses his own despair—that convinced Wilder to direct his own material in future. The rest is movie history.

March 4, 2022

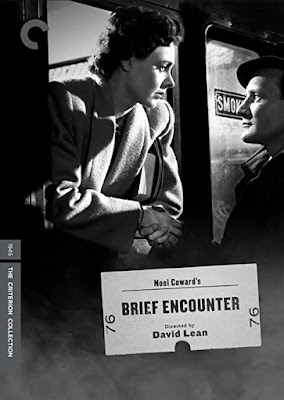

A Brief Encounter with “Brief Encounter”

Brief Encounter is a relatively short (of course!) British film released in 1945, but reflecting the period before World War II wrenched English domestic life asunder. Several names associated with the film may seem, to the modern movie-goer. to be out of place. Noel Coward, on whose short play Brief Encounter was based, is usually associated with upper-class wit and martinis extra dry. Director David Lean is revered for his towering wide-screen epics, among them Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago. Male lead Trevor Howard, just starting his acting career in 1945, became known for playing authority figures, like Napoleon, Captain Bligh and a variety of popes and military men. Romantic roles were never his specialty.

And yet this relatively modest black & white film is cherished by those who adore a good love story with a stiff-upper-lip ending. It took me years to catch up with it on video, but I’m glad I did. I’m also glad I listened to the post-film commentary, which gave me a great deal to contemplate. Though I’ve read a fair number of Noel Coward plays (among them the ultra-sophisticated Private Lives and Design for Living), I don’t know Still Life, which provided the source material for Brief Encounter. Apparently its trajectory is much the same as Brief Encounter: a youngish wife and mother falls passionately in love with a married doctor she meets by chance in the lunch room of a suburban railway station. Their serious but ultimately doomed romance is played off against the comic flirtation of another couple, a lower-class ticket collector and the not-so-youthful woman who runs the railway buffet. In its stage premiere the central roles were played by Coward himself and his longtime close friend, Gertrude Lawrence. Audiences loved it, particularly its heart-in-the-throat ending in which a stab at a passionate farewell is disrupted by the unexpected appearance of the leading lady’s chatty female friend.

I learned from the commentary that Coward’s play is balanced between the emotions of the wife, restless in an affectionate but dull marriage, and the doctor who falls hard for her. Both characters, while luxuriating in the passion they feel for one another, have no desire to overthrow their solid domestic arrangements. It’s hardly a surprise that middle-class mores ultimately win out: they’re English, after all.

In the film version, however, we’re entirely in the head of Laura, played by Celia Johnson. I don’t know her work in other films, but here Johnson has the ability to look plain, even mousy, in some scenes, but absolutely radiant in others. When she joyously laughs at her lover’s antics, it’s hard to imagine anyone more adorable. At home she’s the dutiful wife and mother, knitting by the fire as her husband works a crossword puzzle. But when her weekly trip to a neighboring town to do some shopping and see a movie unexpectedly turns into a series of trysts with a romantically-inclined man of medicine, she becomes quite a different person.

Though I loved seeing Laura blossom as romance comes her way, I was never so sure about her romantic partner. Is he as fully swept away by forbidden love as she is? We see Laura’s habits—the Rachmaninoff concerto she listens to on the radio, the romantic novels she borrows from the lending library—and understand full well her dreams. But Howard’s Alec? His home life is withheld from us, and we wonder how the good doctor manages to consistently shirk his hospital duties. He’s the active one in moving the romance forward. Is he, perhaps, simply looking for a good lay?

March 1, 2022

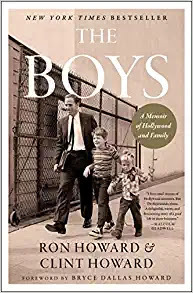

The Howard Boys Strike Out on Their Own

Happy birthday to Ron Howard, 68 years old today.

Early in this century, while researching my Ron Howard: From Mayberry to the Moon . . . and Beyond, I wrote a polite letter to my subject, requesting his cooperation on the project. The note he sent back to me was a polite turn-down: Howard explained that he wasn’t yet ready to step back and assess his own life story. Someday he hoped to be able to write his own memoir. Expecting no less, I continued on with my own book, one that was published in 2003 and turned into an audiobook just last year.

(A much less polite turn-down came from the head of Howard’s company, Imagine Entertainment. When I got this pompous man on the phone, he fumed, “How dare you? What right do you have?” As an honest journalist researching a major public figure, I had every right, but that’s another story.)

A few months back, Ron Howard made good on his dream of writing up his memories himself. Along with brother Clint, he has published The Boys: A Memoir of Hollywood and Family. The Howards have dedicated the book to their now-deceased parents, Rance and Jean Howard. If their musings sound potentially saccharine and self-serving, believe me that they’re not. One thing the two brothers clearly learned from their salt-of-the-earth parents is the value of truth-telling. Rance Howard, from all accounts, always wanted to be straight with his sons when they asked awkward questions, even in their tender years. That’s why, when Jean was expecting Clint, Rance drew crude stick figures to explain to little Ronny how babies get conceived, And on the set of The Andy Griffith Show, Rance was at pains to explain to young Clint the meaning of the drawings on the men’s room walls, even while warning Clint never to take up the practice.

So “the boys,” paying tribute to their parents, are frank about the joys and woes of growing up as child actors. They recognize the unparalleled opportunities to which their careers gave them access, as well as the awkward fact that by being TV celebrities attending a middle-class public school they were doomed to struggle to fit in. They are both candid and colloquial in their narration of what it was like to be “different” during their school years. And they freely acknowledge that in some ways their youthful success (particularly that of Ron, featured in The Music Man as well as TV’s Andy Griffith Show and later Happy Days) was tough on their actor-father who never moved beyond being a journeyman thespian, mostly cast in modest roles in his sons’ projects.

Alternating as narrators, Ron and Clint present their own take on the life they’ve led. Ron details his adolescent angst when his career seemed to be drying up, as well as the way he finally was able to switch from acting to directing, thanks to Roger Corman’s penchant for giving “name” actors a shot at the director’s chair, so long as they were comfortable with sex, violence, and low-budget production values. The rambunctious Clint, meanwhile, is frank about the struggles with drug and alcohol addiction that began in high school. Because the book ends as Ron, in his twenties, is launching his directing career and Clint is making the shift from juvenile roles into character acting (with a specialty in outrageous performances), we aren’t treated to an in-depth look at the Howards’ adult years.

I’m thrilled that Ron picks up one of my own themes, explaining his passion for stories about bold leaps in terms of his parents’ audacious runaway wedding. I, for one, say “More, please.”

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers