Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 33

August 23, 2022

A Minority Report on “Minority Report”

There was a time when I thought the hallmark of Steven Spielberg’s films was their simplicity: straight-ahead stories told with visual flair. Remember Jaws: huge fish suddenly bursting out of the ocean. Or E.T. a boy on a bike, soaring aloft with an extraterrestrial on his handlebars. It’s akin to the lesson I learned from my own mentor, Roger Corman: the poster is the movie. Those Spielberg masterworks were made more than 40 years ago, and Spielberg has long since learned to exploit other aspects of his talent. I deeply admire the panache of the Indiana Jones films, the historical profundity of Schindler’s List (1993), the whimsy of Catch Me If You Can (2002), and the moral complexity of Bridge of Spies (2015). Spielberg’s sensitive 2021 retooling of West Side Story worked far better than I expected.

Yet Spielberg’s approach to science fiction is perhaps too visually and thematically cluttered to impress me. I do remember liking 2001’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence, because its central focus on a robotic boy who yearns to be human has emotional resonance. Minority Report, a 2002 film based loosely on a story by Philip K. Dick, explores a futuristic society caught up in another conundrum: how to stop crimes before they happen. An elaborate experimental system, called Precrime, halts murderers in their tracks by seeking out and arresting those who are about to kill a fellow human being. Spielberg creates a big visual splash when a team of commandos, led by stalwart Tom Cruise, rappel onto the scene of a domestic quarrel and arrest a man who may (or may not) have been just about to pull the trigger.

But philosophical issues of intent aside, Minority Report goes a bit crazy with its production design. As in the previous Dick story that became the futuristic screen classic, Blade Runner, prophetic visuals are all-important here. Such witty touches as cereal boxes that talk to consumers and video-wall ads that address prospective customers by name are amusing enough, showing us a future world, in which consumerism reigns supreme. More importantly, Spielberg obsesses on the architectural look of the mid-21st century. He starts us off slowly by setting his first scene in a classic Washington DC townhouse, full of bookcases and plush furniture. But then we’re whisked into the headquarters of Precrime, in which everything is sleek and high-tech and gadget-driven. Pretty soon good-guy Cruise (who of course is nursing a family sorrow) is suspected of being one of those about-to-kill baddies, which sets the stage for a lengthy, exhausting chase through the streets of a DC that’s now fully space-age. Action fans (and of course Tom Cruise enthusiasts) doubtless love this section, but it hasn’t much of anything to do with the serious intellectual questions with which Minority Report theoretically wants to wrestle.

Then there’s the source of the information about those soon-to-happen crimes. For all their gadgets, the scientists and tech guys in this film are not dealing with anything so sophisticated as probability tables. Instead, it turns out that the source of their information about future crimes comes from three very bizarre, very water-logged humans, the Precogs, who are submerged in a secret wading pool. Like the seers of old, they know what’s about to happen. Really? Kinda like the weird sisters in Macbeth? Yup, and all this has something to do with the red ping-pong ball that slides down a chute and announces to the Precrime staff that a murder is about to occur.

Gadgetry—thy name is Spielberg? Please, Steve, stick to good stories peopled by real characters.

August 19, 2022

Ascending the High Sierras: Bogart Died Here

Humphrey Bogart got second billing on High Sierra, but you’d never know it. When the Warner Bros. crime thriller was released in 1941, Bogart had already made a name for himself in cold-blooded killer roles, starting with the screen version of his electrifying performance in Broadway’s The Petrified Forest (1935), opposite good-guy Leslie Howard. But his studio already had George Raft, James Cagney, and Edward G. Robinson on its payroll, and for a time it seemed Bogart would never be anything but a sidekick.

This all changed in 1941, with High Sierra, a novel adapted for the screen by his drinking buddy John Huston. Fortunately for his career, Paul Muni, Raft, Cagney, and Robinson all turned down the part before it came to him. Bogey may have been billed second to Ida Lupino (playing a tough, loyal gal who’s been around the block a time or two), but the film is hisstory all the way. He plays yet another criminal, one who has just been released from prison and immediately returns to a life of thievery and worse. But his Roy “Mad Dog” Earle is a complicated man who is not without a soft side. Roy loves nature, and seems to yearn for the simple life he knew on the family farm back in Indiana. He also loves pretty women, whom he treats with a respect that borders on the courtly. And he also has great affection for animals, like the little dog who plays a key role in the plot. In the film, we don’t know quite why he has deviated from the straight and narrow path, but sense that there’s a concealed trauma behind his lawless ways.

The film is full of action, including a deadly robbery at a swank hotel in a resort area that is clearly modeled after Palm Springs, California. It takes its title from a climactic shoot-out, with Bogart’s character perched high on a Sierra Nevada peak, as crowds of law enforcement and looky-loo types gather below. Because of the strictures spelled out in the infamous Production Code, we know that in movies of this era crime never pays, and so there’s no point in hoping for Roy Earle’s survival. Still, his character is so appealing that we can’t help wishing him well.

I suspect the audiences of 1941 felt the same way. High Sierra became the pivotal film of Bogart’s career, the one that elevated him to leading-man status. Also in 1941 he graduated into the role of melancholy private detective Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon, then followed this up by playing Philip Marlowe in The Big Sleep. His unusual combination of toughness and softness made him a natural for film noir, but he also revealed a memorable romantic side in Casablanca and, later, in The African Queen. And his real-life love story with actress Lauren Bacall, triggered by their on-screen chemistry in To Have and Have Not (1944) was fodder for fan magazines around the globe..

High Sierra was not life-changing only for Bogart. John Huston, the son of a legendary actor, started out in Hollywood as a screenwriter. Beginning in 1930, he had ten screenplay credits before High Sierra, some on big-name pictures like Jezebel and Juarez. But after High Sierra, which was directed by action-specialist Raoul Walsh, Huston moved into the director’s chair, starting with The Maltese Falcon and continuing until 1987, when he directed a poignant adaptation of James Joyce’s The Dead. The grand total for Huston as a director: 38 films in all, with The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Moulin Rouge, and Prizzi’s Honor among them.

August 16, 2022

Anne Heche: Looking Back in Sorrow . . . And Frustration

Yes, I feel bad about Anne Heche’s final days. Clearly there is something terribly wrong when a talented woman gets into a senseless accident that destroys her life. The fact that she had experienced other bizarre encounters, both on the day of her final crash and years before, suggests that she was suffering from mental issues that no one could permanently solve. It’s tragic, but it happens.

What nags at me, though, is the fact that we’re all lamenting Heche’s lost promise, with little thought for the woman whose life she so permanently upended. On August 5, a Mini Cooper driven by Heche crashed into the garage of a West L.A. apartment building, narrowly missed hitting a pedestrian, and struck a Jaguar. Shortly thereafter, it smashed through a small rental house on Walgrove Avenue, destroying the front wall and lodging in the rear, where it burst into flames. Thankfully, the occupant managed—with the help of neighbors—to save herself and her pets, but after some fifty-nine firefighters converged to put out the blaze, most of her belongings (as well as her home itself) were toast. Remarkably, this newly bereft L.A. woman has had the grace to express on Instagram her condolences to Heche’s family. But will the public outpouring of grief for Heche and her bereaved kin extend to the person whose life she has irretrievably altered?

Maybe it’s the fact that the destroyed house is perhaps ten minutes from the peaceful street on which I live that makes me so sensitive to the losses suffered by innocent bystanders. But I’ve got to say that living in Movieland is not always easy for us civilians. True, I’ve had the thrill of seeing (and sometimes interacting with) celebrities in their native habitat Many are gracious to members of the public, and I’ve certainly read about hugely good deeds done out of the spotlight. But it’s also true that successful creative types seem prone to lapsed judgment, often involving alcohol, drugs, and very fast cars. I’ve just been reading back over the details of Charlie Sheen’s checkered career. Sheen mostly seemed to do harm to those he married, but other Tinseltown figures have come closer to injuring complete strangers in their vicinity. There was, for instance, Mel Gibson, who was stopped by a Malibu cop for driving under the influence, then responded with anti-Semitic threats to the arresting officer A special case, I suppose, is that of Margot Kidder, who—having rejected a medical diagnosis of bipolar disorder—was found in a distressed state of mind wandering in a homeowner’s Glendale backyard.

Of course it’s not just entertainment figures who wind up creating havoc for those around them. A tragic story covered by the Los Angeles Times occurred just one day before Heche’s Mar Vista misadventure. In a section of L.A. known as Windsor Hills, a Mercedes traveling at 90 miles an hour sped through a red light and crashed. The result: five people died, including a pregnant woman and a very young child. The horror of the situation was compounded when news surfaced that the driver of the Mercedes was a longtime nurse, much respected in the community for her compassion and her medical skills. (Somehow her 13 previous crashes had never affected her license to drive a motor vehicle.)

What’s my point in all this? People—both famous and not—are complicated. And mental illness can bubble up anywhere. But I can’t help wishing that we spent less time mourning troubled celebrities who cause harm, and more time focusing on the plight of their unfortunate victims.

August 12, 2022

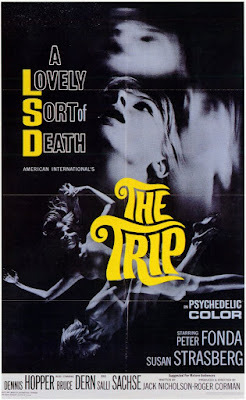

Roger Corman: The Man with Kaleidoscope Eyes Strikes Again

Early in the 21stcentury a writer and editor named Tim Lucas—a fan of my Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers--slipped me a copy of a script he had written, along with his pal, Charlie Largent. It was a clever dramatization of an incident known to all Corman enthusiasts: the 1966 jaunt that Roger took to Big Sur, California, in preparation for shooting the movie that became The Trip. The straight-arrow Corman, getting ready to film Hollywood’s first flick exploring the allure of LSD, had been persuaded by both screenwriter Jack Nicholson (yes, that Jack Nicholson) and star Peter Fonda that he couldn’t film an acid-trip story without having first dropped acid himself. And so he did.

The Lucas/Largent script found its way into the hands of Corman protégé Joe Dante, who signed on to direct and produce. Eventually two more screenwriters got involved—Michael Almereyda and James Robinson—and the title evolved from Sunshine Boulevard into The Man with Kaleidoscope Eyes. At one point Oscar-winner Colin Firth committed to playing Roger. But, like so many Hollywood projects, this one never got funded. Its biggest hurrah was a live script reading at a local L.A. theatre, with Roger himself participating, and Bill Hader in the Corman role.

Nothing daunted, Tim Lucas has now turned The Man with Kaleidoscope Eyes into a novel that pop culture fans will cherish. Having done his research, Lucas revels in the minutiae of Roger Corman’s lifestyle (the fancy cars and austere Metrecal lunches; the obsessive punctuality and zeal for problem-solving). He also paints vivid portraits of such Corman cronies as Fonda, Nicholson, resident hippie Chuck Griffith, and director-in-the-making Peter Bogdanovich, who liked to present himself as something of a dandy (“His ascot was the color of the velvet curtains in a roadshow cinema”). Then there’s Roger’s plucky Oxford-schooled assistant, Frances Doel, who seems prescient in her ability to anticipate her boss’s every need. (Frances, a close friend of mine, finds her own portrayal hugely annoying, but I chalk that up to her intrinsic modesty.)

Lucas has a ball depicting the commercial stretch of Sunset Blvd. in its flashy, trashy heyday. As he wittily puts it, “Contrary to its name, Sunset was actually where the sun rose—on the American dream.” He revels in the oversized billboards that dotted the street, promoting such cinematic fare as Born Free, The Endless Summer, and Corman’s own unlikely 1966 hit, The Wild Angels. It’s all part of what he calls “the phantasmagorical bazaar that was the Sunset Strip on a Friday night in the summer of 1966—the Summer of Foreplay before the Summer of Love.”

He also finds ways to work into his narrative tidbits of Corman’s personal and professional life, finding a place for Roger’s first creative breakthrough (The Day the World Ended) and his all-time gutsiest stab at social commentary (The Intruder). There’s playful quoting from The Little Shop of Horrors (“Novocaine . . . it dulls the senses”) and, in an eerier vein, X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes (“I can still see!”) As a tribute to Nicholson’s eventual star role in The Shining, he slips in a reference to how “all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.” My favorite insider gag: a highly fictitious account of how the scruffy LSD supplier is promised, in return for a serious discount, an associate producer credit.

Lucas’s determination to add a romantic thread involving the future Mrs. Corman may be a stretch, but it gives the ending of this book a surprising sweetness. Well done, sir!

August 9, 2022

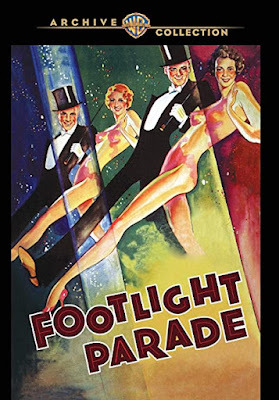

The World According to Busby Berkeley: “Garp” and “Footlight Parade”

I don’t ever walk out on movies in theatres, even when they fail to fulfill my expectations. But there are times when, sitting on my couch at home, I realize it’s just not worth my time to continue watching something I find dreary. Such was the case with The World According to Garp, George Roy Hill’s 1982 adaptation of John Irving’s bestselling saga about eccentric people and random acts of violence. Never having read the novel, I can’t comment on the film’s fidelity to its source. But such actors as Robin Williams in the title role, Glenn Close (in her screen debut) as his gutsy mother, and John Lithgow as a star-football-player-turned-transsexual are always fun to watch—until they aren’t. When the opening scene introduced a charming cameo by stage greats Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy as Close’s parents, horrified by her flouting of social convention to the point of fainting dead away, I was ready to buy into the whole megillah. But approaching the two-hour mark, I’d had enough.

Which is why I turned to something reliably amiable: the 1933 Warner Bros. pre-code classic, Footlight Parade. Like other Warner Bros. musicals of this era—including 42nd Streetand Golddiggers of 1933—Footlight Parade features clunky tap-dancing by Ruby Keeler and gags galore by other members of the WB stock company. Story? There’s always a bit of romance and a bit of back-stage drama. But what’s important is that these films, reveling in the opportunity presented by the coming of sound to the motion picture industry, lean heavily on exotic musical numbers choreographed by the P.T. Barnum of Hollywood musicals, the man with the unlikely moniker of Busby Berkeley. This is especially true of Footlight Parade, in which the three most audacious numbers are presented, one after another, to form the film’s climax.

As always, there isn’t much plot. James Cagney, calling upon his naturally authoritative presence as well as his past career as a song-and-dance man, is a producer/director of Broadway musicals. Because they’re being replaced in the public’s mind with motion-picture talkies, his business is on the rocks . . . until he realizes he can produce the live-action “prologues” then popular on the motion picture circuit, as lead-ins to the feature films. His wife has left him; his smart, sassy secretary (Joan Blondell) quietly pines for his love. Meanwhile an upstart young tenor (Dick Powell) gets his big break, and discovers he’ll be playing opposite another office staffer (Ruby Keeler), who downplays the fact that she’s an ace musical performer. But what’s really urgent is Cagney proving his mettle by staging three elaborate prologues for a wealthy would-be backer on one New York evening.

The three production numbers presented back-to-back-to-back are pure Busby Berkeley. The first, “Honeymoon Hotel,” is a naughty little fantasy about two just-marrieds capering through a hotel full of knowing lovers, all of whom have registered as Mr. and Mrs. Smith. The last, in which Cagney shows off his terpsichorean talents as a sailor looking for his Shanghai Lil, features Keeler impersonating a cute China doll in ways that today would seem appalling. The most classic Berkeley of the bunch is “By a Waterfall,” showcasing scores of beautiful blondes in skimpy attire. They cascade joyfully into a pool, and then reassemble for a kaleidoscopic water ballet. What we see on screen—the crane shots, the underwater filming—would of course be impossible in an actual theatre. This movie may be a salute to live entertainment, but only motion pictures could bring these dazzling moments to life.

August 5, 2022

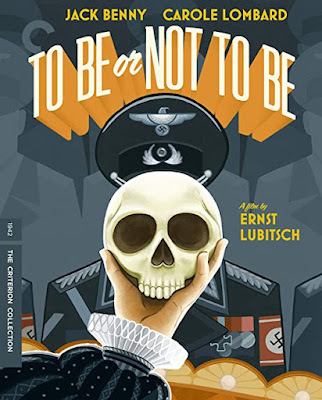

Heil, Myself! Ernst Lubitsch’s “To Be or Not to Be”

Old-school comedian Jack Benny playing Hamlet? That seems about as unlikely as a Polish theatre troupe, circa 1939, successfully impersonating Hitler and his goons to fool the Gestapo. But both of these things happen in a remarkable (and remarkably serious) comedy that emerged from Hollywood in 1942, while war raged in Europe.

Benny, mostly known for the radio (and eventually TV) show that spoofed his tightwad image, wears tights for real as he stars as the hammiest of ham actors. His biggest concerns, as actor Joseph Tura, seem to be the adoration of his fans and the possibly roving eye of his beautiful wife, played by Carole Lombard in her final role. (Alas, Lombard died ina a plane crash at age 33, shortly before the film opened, while returning from a war bonds tour.) But while the company is rehearsing an anti-German drama, Gestapo, the Nazis march into Warsaw and swiftly take over. Suddenly patriotism comes to the fore, and all the members of the company unite to thwart the will of their new German overlords.

Theatre troupes make for strange bedfellows, but in this crisis everyone pitches in wholeheartedly. The glamorous Maria Tura (Lombard) strategically cozies up to a turncoat, insinuating she’d be glad to spy for the Nazis as a way of allying herself with the winning team. The obviously Jewish spear carrier who longs to play Shylock gets his chance at a critical juncture to recite his big speech and be a key diversion—and a hero. The Polish flyboy (Robert Stack) who yearns to take Maria away from her husband uses his aviation connections to save everyone’s neck. And Jack Benny’s Joseph Tura dives into a trunkful of fake mustaches and beards to impersonate prominent Nazi leaders, befuddling the pompous Sig Ruman, who hilariously plays the local Gestapo commandant .

It's all uproariously funny, except that the movie never forgets what the stakes are for these people, who are human beings first, actors second. With death and destruction all around them, they balance on a knife-edge between triumph and disaster. Call it the comedy of desperation. The Berlin-born Lubitsch may have been known for the worldly elegance of so many of his films (like Trouble in Paradise), but he remained at heart an immigrant, the son of a Jewish tailor who had moved to Germany from the outskirts of the Russian Empire. In other words, Lubitsch was not entirely at home in a world where borders kept changing and tribal identities were key. Commentators have pointed out that the one character in the film who is by no means ever comic is the Polish-born scholar with a prominent academic post in Britain but a secret commitment to the Third Reich.

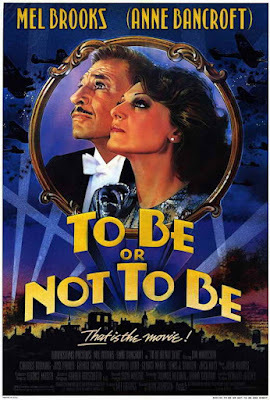

As the plot continues to thicken, it’s pretty much impossible to follow the ins and outs of a story in which the good guys impersonate the bad. My advice: just relax and enjoy the chaos, knowing that, thankfully, it will come out all right in the end. The title phrase, To Be or Not to Be, is of course from Hamlet’s great soliloquy, but it takes on several alternative meanings in the course of the film, even signaling an upcoming assignation. There’s no question that funnyman Mel Brooks enjoyed the joke (as he did the phrase, “Heil, myself!” which later shows up in Brooks’ The Producers). In 1983, four decades after the original, Brooks shot his own version, with wife Anne Bancroft as the glamorous Maria, Charles Durning assuming a highly-ersatz German accent as the commandant, and himself chewing the scenery in the Jack Benny part.

August 2, 2022

Choosing Between The Devil and Miss Jones

If you think The Devil and Miss Jones is an adult film akin to Deep Throat, you’re in the wrong era (and the wrong mindset) entirely. In 1973, one year after the frankly pornographic Deep Throat became a surprise success among hip moviegoers, its filmmaker, Gerard Damiano, launched a second film, coyly titling it The Devil in Miss Jones. No, I’ve never seen it.

But I’ve just watched The Devil and Miss Jones, and been pleasantly surprised.. Released by RKO in 1941, this is a whimsical workplace comedy, starring Jean Arthur, whose stellar career stretched from silent movies to 1953’s Shane. This vibrant gal with the distinctively throaty voice may be best remembered for Mr. Deeds Goes to Town and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. But she’s never been more memorable than as Mary Jones, a New York department store salesclerk with a yen for a would-be union organizer played by the young Bob Cummings. Forget about that title: this is not a supernatural fable, like Cabin in the Sky. Though the ecstatically happy ending is clearly a fantasy, there’s no devil here, unless you mean the apparently heartless business tycoon brilliantly played by Charles Coburn. Looking down at the world from his mansion just off Bryant Park, he scorns the common folk who labor in the department store that’s part of his vast holdings. When some of them dare to demonstrate against upper management, parading with an effigy that represents him, he vows revenge. But things hardly work out as planned.

For various reasons, Coburn’s character decides to personally masquerade as a department-store clerk, the better to spy on the rebel faction on the fifth floor. Pretending to be the amiable, unsophisticated Tom, he sets about selling men’s and women’s slippers, under the tutelage of the spunky Mary. Wouldn’t you know it? He comes to respect the hardworking employees who try their best, but are often undercut by managerial types who don’t understand their issues.

Everything comes to a head on a day-off trip to Coney Island, where Mary speaks eloquently about her love for her beau, while Coburn’s tycoon becomes more and more enamored of the gentle Elizabeth (Spring Byington), who frankly muses to him that she could never marry a rich man for fear of doubting her own motives. There’s also a kerfuffle over the wine he’s brought along: the others in the party, unused to anything other than the rotgut made by a janitor stomping grapes in his bathtub, disdain his priceless vintage and try to add soda-pop to kill its taste. Oh yes, there’s also eventually a near-arrest, followed by a trip to the police station, where things look bad for our main character until Mary’s swain quotes dollops of the U.S. Constitution, bravely defying authority figures and winning Coburn’s respect.

The cinematography in this film—always vivid—takes on special dimensions in these beach scenes, as director Sam Wood crams his frame with hordes of frolicking extras, making clear how hard it is for the working class to find privacy, even during leisure hours. There are also some terrific opening shots in which the tycoon’s cadre of toadies are driven up to his mansion, one after the other, in their sleek black limousines: the cars are filmed at such a low angle that they look like monstrous beasts of prey.

Despite the star presence of Jean Arthur, this is largely third-billed Coburn’s show, as we see him melt from ferociousness into joviality. His is one of two Oscar nominations earned by The Devil and Miss Jones. The other, well-deserved, is for Norman Krasna’s script.

July 29, 2022

Choosing the Best Man

Watching The Best Man, based on Gore Vidal’s hit Broadway play, I’m reminded of how much has—and hasn’t—changed in American politics over the past six decades. In 1960, when Vidal wrote his play, presidential candidates for the two major parties were still chosen at raucous political conventions whose outcomes were generally uncertain. And of course everyone was white and male, except for the dutiful spouses of the candidates, who knew how to smile on cue. But much remains the same: the party hacks running the show, the reporters eager for a scoop, the fact that some candidates will do just about anything to come out on top. To be, in other words, anointed the best man for the highest office in the land.

Watching The Best Man, based on Gore Vidal’s hit Broadway play, I’m reminded of how much has—and hasn’t—changed in American politics over the past six decades. In 1960, when Vidal wrote his play, presidential candidates for the two major parties were still chosen at raucous political conventions whose outcomes were generally uncertain. And of course everyone was white and male, except for the dutiful spouses of the candidates, who knew how to smile on cue. But much remains the same: the party hacks running the show, the reporters eager for a scoop, the fact that some candidates will do just about anything to come out on top. To be, in other words, anointed the best man for the highest office in the land. Within the scope of the play, the political party in question was never named. But Vidal, who had strong (and sometimes cranky) political opinions, was clearly committed to putting his own views into a lively story about political skullduggery on the highest level. The play opened early in the same year that the Democrats were planning a presidential nominating convention in Los Angeles. The folksy but ultimately shrewd former president is clearly based on Harry Truman. (He was played both on stage and on screen by the invaluable Lee Tracy, who was nominated for a supporting actor Oscar for this role.) One leading candidate, a witty intellectual, reflects the style of Adlai Stevenson, who was twice the Democratic nominee against Dwight D. Eisenhower. His chief rival, who has adopted a far more grandstanding manner, is apparently a combination of the politicos Vidal distrusted: the up-and-coming John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon, et al.

When the film was made four years later, the 1960 election was long over. But viewers can identify L.A. landmarks of the era: the Ambassador Hotel; the Los Angeles Coliseum, the Sports Arena where the real JFK accepted his party’s nomination. And the hurly-burly of the convention floor is shot very effectively, conveying a true sense of being present as history unfolds. (Franklin Schaffner, mostly known for TV in 1964, kicked off a major film directing career with The Best Man.) The two rival candidates are played by Henry Fonda—as an idealist who can’t easily bring himself to fight dirty—and Cliff Robertson, as a pragmatist with the guts to do what it takes to win. Which of them will make the better president? The former president’s all-important endorsement is up for grabs, and there’s a lot of dirty linen around, just waiting to be aired. Far be it from me to spill all the beans, but this was the first Hollywood film ever to use the word “homosexual.” Vidal’s well-structured story keeps us continually off-balance, leading to an ending that’s both happy and sad . . . and altogether satisfactory as a way to wrap up this mesmerizing tale.

I should mention the rest of the strong cast, which includes Margaret Leighton as Fonda’s starchy British wife, Edie Adams as Robertson’s kittenish spouse, and (surprisingly) funnyman Shelly Berman in a small but key role. There’s also Ann Sothern as the rare female party operative, one who thinks of herself as the spokesperson for every woman in America. And I don’t want to overlook the film’s producers, who include veteran Stuart Millar and his protégé, the young Lawrence Turman. Turman, who yearned to produce a hit film all on his own, got his wish in 1967, with The Graduate. Larry was a huge help to me on my Seduced by Mrs. Robinson. He’s now 95, and I wish him continued health.

July 26, 2022

Taking the 3:10 to Yuma . . . and the National Film Registry

My own memories of Glenn Ford’s lengthy movie career start with a 1956 comedy, The Teahouse of the August Moon, in which he starred as a good-hearted military man dealing with cultural disconnects while stationed in a village in post-WWII Okinawa. (This adaptation of a Broadway hit – featuring Marlon Brando as a wily Okinawan native -- would surely be condemned for ethnic insensitivity today, but in its own era it was widely considered charming.) I got to know Teahouse as a kid, and even appeared in several little theatre productions, with no apparent harm done. But it was only years later that I saw Ford in tougher fare, playing the beleaguered inner-city teacher in The Blackboard Jungle and especially the ambiguously devoted suitor opposite Rita Hayworth in Gilda.

Ford’s son Peter, the product of his troubled marriage to Eleanor Parker, has long been exploring his dad’s legacy. He sees in his father—who was among other things a compulsive womanizer--a dark side that his best roles exploit. Peter’s commentary on the DVD of the 1957 western classic, 3:10 to Yuma reveals that the western was Ford’s preferred movie genre. Having worked for Will Rogers as a ranch hand (while still a student at Santa Monica High School), he was highly comfortable around horses. And 3:10 to Yuma¸ adapted from an early-career story by Elmore Leonard, was one of his very favorites. Leonard is of course far better known for the noirish novels that became movies like Get Shorty and Jackie Brown. But he started out writing western stories for pulp magazines. The kernel of the story that became 3:10 to Yuma involves a rancher, an upright family man. Plagued by drought and the loss of many head of cattle, he accepts a pittance to put a notorious outlaw on a train to the Arizona city where he’s destined to stand trial. The heart of the story, and the film, is the long stretch of time spent in a Contention City hotel room where the outlaw tries to threaten, to cajole, and to bribe the rancher to turn him loose before the train arrives.

According to Peter Ford, his father, then at the height of his celebrity, was first offered the role of the straight-arrow rancher. It eventually went to Van Heflin (who’d played a similar nice-guy role in Shane), so that Glenn Ford could show off his wily charm as the outlaw. You almost believe him when he insists he’s not as much of a troublemaker as his reputation implies. The scenes between the two men in that hotel room do a great job of ratcheting up the tension as, out on the street, Heflin’s supporters melt away out of fear of Ford’s gathering cronies. There’s something of High Noon in the ticking-clock plotting, though good and evil are not nearly so clearly demarcated as they were in that Gary Cooper classic. Among the Ford character’s virtues is a genuine gallantry toward women (there’s a high-octane encounter between him and a pretty but lonesome barmaid played by Felicia Farr). He’s also able to truly recognize the heroism implicit in Heflin’s stubborn insistence on holding to his end of a bargain.

3:10 to Yuma was remade in 2007, with the main roles played by born-again westerners Russell Crowe and Christian Bale. Naturally, the new film featured much more bloodshed and much more corrupt behavior than the original, but critics and audiences seemed reasonably impressed. It was the 1957 original, though, that has found a home in the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

July 22, 2022

What Goes Around Comes Around: “360”

One thing we’ve learned in the era of COVID is that we’re all in this together. Particularly as we return to international travel, we’re re-discovering (via transmitted infections that are now running rampant around the globe) that, in the famous words of John Donne, no man is an island. That’s one of many thoughts that came to me in the wake of watching Fernando Meirelles’ 2011 film, 360. This structurally ambitious drama (it’s not for nothing that Meirelles once studied to be an architect) was written by the eminent Peter Morgan, best known for such royal projects as The Queen, The Crown, and The Last King of Scotland. Critics and audiences were not charmed by 360, and I can understand how the film’s intricacies will seem to some overly calculated. But my late-night viewing of this unheralded film left me with much to mull over.

In some obvious ways, 360 owes a debt to Arthur Schnitzler’s notorious 1897 play, La Ronde. Schnitzler broke international taboos by depicting diverse pairs of lovers (a soldier, a housemaid, a young gentleman, and so on) before or after coitus. One of the pair in each scene moves on to another tryst in the next, hinting that sexuality knows no boundaries of class and economic status Eventually we come full circle, with the prostitute-character from the very first scene bedding the nobleman introduced near the end. (Schnitzler does not concern himself with relationships transcending conventional gender roles, but his play outraged audiences of his own day and led to attacks on his character and his ethnicity.)

In 360, too, many of the interlocking relationships are based on sex, but characters are considerably more complicated. As in: the British familyman played by Jude Law, while on a business trip to Vienna, has nervously set up an assignation with an ambitious would-be prostitute from Slovakia. By chance it doesn’t happen, but she re-enters the film much later, making a killing (so to speak) as part of a scheme to rob a ruthless gangster-type. Obviously, part of the film’s point is that you never know what will happen when you intersect with other human beings. Sometimes, in fact, great things may come to pass, if you’re only brave enough to seize the day. (Says one newly-emboldened character, “If you see a fork in the road, take it.”) On the other hand, audacity can also lead to tragedy. One memorable strand involves a young Brazilian (Maria Flor) living in London. Fleeing her two-timing lover, she boards a plane to fly home, meeting on the way a wistful old Brit (Anthony Hopkins) searching for his long-lost daughter. Their brief encounter is enlivening to both of them, but an unexpected weather delay in the Denver airport puts her in the path of a convicted sex offender (Ben Foster) who’s desperately trying to control his illicit desires, at the same time that she’sexperimenting with carefree hedonism.

The production leans hard on a stellar international cast speaking a babel of diverse tongues. (Several of the characters are tied together by their serious struggles to learn English.) 360 was shot on location in Britain, France, Austria, and elsewhere, suggesting the degree to which our world has shrunk due to airline travel. Stylistically, Meirelles does wonderful things with glass panels and reflecting surfaces. In diverging from Schnitzler’s La Ronde, it feels modern in both its story and in its film aesthetic. I could pick it apart, but why do that? Frankly, I do not want to spoil my memories of a splendid diversion from my own humdrum summer days.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers