Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 31

November 1, 2022

A Dark and Sticky Tár

Why is Todd Field’s new movie called Tár? The obvious answer is that it dervies from the last name of its leading character, a renowned symphonic conductor who’s American, though apparently of Eastern European descent. But I suspect that in the back of Field’s mind he had a more homely meaning of the word “tar.” What is tar (without the accent) but a useful yet annoying substance, one that sticks to everything, and you can’t be rid of it? Maybe I’m overreaching, but this seems to describe Lydia Tár's life. Despite the fact that the music world regards her with awe, she’s dealing with memories she can’t forget, worries she can’t sidestep, and longings that get her into serious trouble.

We first meet Lydia Tár at the height of her glory. Though she has a major conducting post as the head of the Berlin Philharmonic, she’s in New York City taking care of business. When she’s interviewed onstage by the New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik about her life as a conductor, a well-dressed crowd hangs onto her every word. (Field’s screenplay works hard to seem both current and au courant. Lydia was apparently a protegee of the late “Lenny” Bernstein;[image error]when she discusses with Gopnik the careers of other female conductors, she casually references Marin Alsop and JoAnn Falletta.)

Back in Berlin, fulfilling a Deutsche Grammophon contract to complete her orchestra’s cycle of Mahler symphonies with the majestic #5, she suddenly seems not quite so sure of herself. Some of the things she’s facing are probably familiar to every conductor who leads a major orchestra: she wants to rid herself of an assistant conductor who’s past his prime; she’s not sure that a new young cellist from Russia will fit in with her potential colleagues in the string section. But there are personal matters as well. Lydia’s romantic liaison with the top violinist who’s also the mother of their child is growing increasingly shaky. And though she’s attracted the world’s admiration for encouraging promising young female conductors via a fellowship program, one candidate has not come to a good end—and Lydia may be to blame.

As the stresses and strains pile up, Lydia becomes hyperaware of her surroundings, to the point where she’ll spring forth from sleep and obsess over sounds that should not be part of her after-hours life. A metronome, for instance, is suddenly ticking off time in the middle of the night.

It’s at that point that a matter-of-fact realistic story suddenly transforms into a kind of horror film. Lydia experiences things that probably didn’t happen, and finds herself in places that don’t make any rational sense. Which leads, at long last, to an evolution in Lydia’s career that she surely wouldn’t have chosen, but one that she approaches with her usual professionalism and with her dignity (at least mostly) intact.

Cate Blanchett serves as a producer as well as star of this film, and I wouldn’t have wanted to go on this journey without her. Through her multilayered performance we see Lydia Tár’s ambition, her passion for music, her fierce determination to go after what she believes in, her vulnerability to lust, and her lingering sense of shame. We see her being both tender and terrifying, sometimes moving with lightning speed from one state of being to the other. Does she deserve what happens to her? Probably so. Would it work out differently if she were male? Again, probably so. In any case, it’s thrilling to see one of our finest actors take on a role that’s worthy of her talent.

October 28, 2022

Guess Who’s Getting Out

Back in 1967, when I was evolving into a movie nerd, one of the nation’s most popular films was a romantic fable introducing the then-bold idea that an interracial marriage could succeed. The film, of course, was Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. Its director was Stanley Kramer, known and respected for such hard-hitting work as The Defiant Ones and Judgment at Nuremberg. Its stars were Hollywood legends Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy (who finished shooting his role a mere 3 weeks before he died), along with Sidney Poitier, America’s favorite Noble Negro. Everyone involved knew that Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner was essentially a fairy-tale, in which all potential social difficulties are swept away by a burst of good feelings, culminating in Tracy and Hepburn joyously celebrating their daughter’s engagement to a man of color. (The plan is for the young couple to spend their married life in Africa, where Poitier’s doctor-character is engaged in doing serious humanitarian work, so that their probable difficulties in building a life in an American suburb are neatly sidestepped.)

Though the film roused in some Americans a great deal of anger (including death threats directed at Kramer and his family), most the country applauded it. It was nominated for ten Oscars, including Best Picture, in a strong movie year, and won two, including a statuette for William Rose’s sentimental but serviceable screenplay. This hardly meant it impressed the intellectuals (of various colors) on both coasts. James Baldwin, for one, quipped, that “asconcerns Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, we can conclude that people have the right to marry whom they choose, especially if we know that they are leaving town as soon as dinner is over.”But a columnist from America’s heartland, Bill Donaldson of the Tulsa Tribune, sagely put the film into historical perspective: “It could not have been successfully released nationally five years ago; it will be hopelessly out of date five years hence.”

It took not 5 but 38 years for Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner to be updated into a laugh-out-loud comedy starring Bernie Mac as a frazzled dad reacting to the surprise of meeting his daughter’s intended (Ashton Kutcher). By 2005, a mildly-humorous social problem play with an uplifting ending had morphed into a farce, with the focus on the Black father’s awkward stabs at accepting a white son-in-law-to-be. The film was a box-office hit, but not exactly Oscar bait.

Then came 2017, when Jordan Peele burst onto the scene with Get Out, which I believe is the first time the basic situation of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner was turned into a horror film, as seen from an African-American point of view. I didn’t check out this film immediately upon its release. When I did watch it on video, all the buzz insured that I pretty much knew what was coming. (What a shame that we so rarely approach horror films in a state of total ignorance: imagine encountering Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde if you had no idea of the relationship between the two men!) Still, in Peele’s film there were a few perverse plot twists I hadn’t anticipated, along with some logic questions I couldn’t help asking. Recently, I watched Get Out again, after being told it’s the rare film that’s so craftily written that it contains no extraneous parts. Quite true, as I’ve discovered: some seemingly random characters and bits of dialogue turn out to be totally essential. Just keep your eye on that central relationship, and discover that the guest who’s coming to dinner may be welcome for all the wrong reasons.

October 25, 2022

The Witching Season

The Witch is not an easy film to like. This 2015 release, written and directed by award-winning indie darling Robert Eggers, is atmospheric but murky. Its characters speak in a sort-of English dialect virtually impossible to understand without turning on subtitles. I’m not sure how successfully The Witch played in theatres, but I suspect it’s best watched at home, with a lot of patience. It’s mostly billed as a horror flick, but there’s hardly a plethora of jump-scares here. Instead this is best seen as a powerful mood-piece, one that calls for some philosophical probing of what’s going on.

The Witch is set in colonial New England, in the same general time and place as the Salem Witch Trials. As a student of literature and a one-time drama kid, I’m deeply familiar with Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, the historical drama about a time in which non-conforming local women (and a few men) were tried and hanged for supposedly consorting with the Devil. Miller, who wrote his play in 1953, was most interested in the social issues raised by the trials. In an era when the Red Scare dominated headlines, when neighbor turned against neighbor in a bid to root out Communists from public life, Miller focused on social hysteria, and on the ways in which unpopular beliefs could be pinned on those without the resources to fight back. The real demonic forces at work in The Crucible are the self-serving majority who blame weaklings and outsiders for any ills affecting the community.

The family at the center of The Witch are not publicly accused of witchcraft. But the film’s opening scene (the only one in which we see a gathering of community members) does start with a trial: William, a proud and stern man with deep Christian convictions, is being cast out of town, apparently because his rigid beliefs don’t align with those of his neighbors. The rest of the film shows William, his wife, and their children (including Anya Taylor-Joy as a young teen) struggling to make a go of it on their small, isolated farm, set against an ominous forest.

Given the hardships of farming life and the intense religiosity of the family (which includes the firm conviction that every human being is born a sinner), it’s not surprising that all of them believe in demonic forces. For the children, there’s both fear and fascination in the possibility that the Devil is on the loose in their vicinity. (The young twins even make a game of it, linking the dangerous-looking barnyard ram to the demon they call Black Phillip.) But the film is not merely about the superstitions of simple folk who lack our own modern outlook on life.. Within the story, diabolical things DO seem to be going on. The first is the sudden disappearance of the family’s youngest child, a mere baby, smack in the middle of a game of patty-cake.. The loss of this tiny boy, which is never given any sort of logical explanation, propels the other members of the household into a kind of spiritual frenzy, with the father desperately trying to hold his family together against tough odds, the mother nursing her personal grievances, and daughter Thomasin (Taylor-Joy) exploring rebellion against her parents and her hard-scrabble life.

The climax, when it comes, is startling but perhaps inevitable. There’s a cascade of tragedies, some mysterious omissions, and a final focus on Thomasin in that forest primeval. Cue the spooky music. The Witch is hardly fun to watch, but it gives you a lot to think about when it’s over.

October 20, 2022

Dancing the Fifties Away: "An American in Paris" and "The Band Wagon"

The Fifties, like the Thirties, went crazy for musicals. In the 1930s, audiences enthralled by the coming of sound flocked to the movie screen flocked to watch their favorite performers sing and dance. In the early 1950s, the advent of television made film producers eager to exploit the color and sound that the TV sets of the day couldn’t emulate. All the major Hollywood studios sought to make musicals, but MGM (under the auspices of producer Arthur Freed) was king.

Not many movie musicals have won the Best Picture Oscar. The big era for musical blockbusters was, surprisingly, the Sixties, the decade of West Side Story, My Fair Lady, TheSound of Music, and Oliver! But in 1951 an ambitious MGM musical carried off the top prize. It was made by showbiz royalty, with Vincente Minnelli directing from an Alan Jay Lerner screenplay. But of course the real star of the show was someone long dead: George Gershwin, the composer of both towering orchestral pieces and popular songs. Gershwin had died of a brain tumor in 1937, at the tragically early age of 38. An American in Paris was a glorious way to re-introduce his music to the multitudes and let it live on.

Of course An American in Paris is about just that—a young American artist (played, of course, by the always jaunty Gene Kelly) falling in love both with Parisian life and with a beautiful young Parisienne (dancer Leslie Caron making her film debut). Kelly’s interactions with his pals and with the young and old residents of his quartier allow for a lot of spritely musical numbers. I particularly like “I Got Rhythm,” performed with a passel of French children trying to master English. And of course there are the wonderful Gershwin love ballads, like “’S Wonderful” and “Our Love is Here to Stay,” for which brother Ira supplied the lyrics. But the real treat comes at the end (unless you happen to be allergic to dream ballets), when Kelly, Caron, and company dance their hearts out to the jazz-inflected Gershwin orchestral piece that gives the film its name. At one point in this long, climactic number, the dancers and poseurs of Toulouse-Lautrec’s Montmartre seem to spring vividly to life which reduced me to tears when first I watched it. (Yes, I was an artsy kid.)

The plot of An American in Paris is admittedly sentimental. There’s lost love, found love, age-inappropriate love, and gloriously appropriate love. Still, inevitably, the female lead is a great deal younger than her male counterpart. Caron, about 20 years old in the film and in life, connects with Kelly (a youthful 40-plus) after severing romantic ties with the guardian who’s older still.

Another Arthur Freed musical of the early 1950s actually has some fun pointing out the age discrepancy between its romantic duo. When he made The Band Wagon (1953), Fred Astaire was about 54, and long past the era when he and Ginger Rogers wee America’s dancing sweethearts The movie posits that he’s a has-been Hollywood star, who’s returning to New York because the silver screen is no longer a welcoming place for him. (When he steps off the train at Grand Central, the press swarms, but it turns out they’re there to photograph Ava Gardner glamorously exiting the next car.) When he’s cast in a Broadway show, the young woman chosen to star opposite him—a prima ballerina played by Cyd Charisse—seems obviously both too young and too tall. Their first meeting is a disaster . . . so it’s inevitable that they’ll fall in love.

October 18, 2022

Fury, But No Sound: “The Artist”

My favorite movie about the impact on Hollywood of the coming of talking pictures will always be Singin’ in the Rain. The 1952 musical directed by Stanley Donen is giddy good fun. Who can improve upon Donald O’Connor’s pratfalls, a lovestruck Gene Kelly swinging from a lamp-post, and Debbie Reynolds smiling through tears? And then there’s the film’s secret weapon: the hilarious Jean Hagen as Lina Lamont, a diva so dumb that she doesn’t realize her screechy speaking voice will be replaced by someone off-camera. Her performance as a self-proclaimed “shimmering, glowing star in the cinema firmament” can never be topped.

The central joke of Singin’ in the Rain is that the elegant creatures who populate the silent screen didn’t necessarily have the vocal chops needed to insure their transition into talkies. The dilemma of the silent star whose career evaporates after the success of 1927’s The Jazz Singer is treated strictly for laughs, at the expense of the Hollywood egotists who won’t, or can’t, adapt to change. But the whole subject is addressed with considerably more gravity in a highly unusual French film from 2011, The Artist. Surveying the same era as Singin’ in the Rain, in which careers are saved by transforming The Dueling Cavalier into The Dancing Cavalier, The Artist also has its gags and its upbeat ending. Still, the plight of a star put out to pasture when talkies replace silents is treated in The Artist with considerably more gravity.

France’s Jean Dujardin won an Oscar for playing George Valentin, an icon of the silent screen who’s cornered the market on swashbuckling roles. I don’t think it’s an accident that Dujardin looks a lot like Gene Kelly in Singin’ in the Rain. He has Kelly’s physical dexterity as well as his patent-leather hair and toothy grin. He also has something of Kelly’s trademark cockiness: early in the film, after the premiere screening of his latest derring-do epic, he appears on stage to take several bows, then delights the well-dressed audience by clowning and showing off some slick dance moves.

What makes The Artist so stylistically unusual is that it is filmed throughout as a silent feature, complete with title cards inserted to give us snatches of dialogue. Even after the public discovers the talking picture, George and those around him convey their thoughts strictly through gesture and facial expression. Within the world of the story, even as George languishes in squalor, the young and vibrant Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo) rises to the top of moviedom because of her musical talents. But we never hear her sing or even speak; like George she’s trapped in the silent movie we’re watching. What’s unique about George, though, is that he seems to resist sound with all of his being. There’s a nightmarish moment (it turns out to be a dream sequence) where he’s suddenly bombarded by sound: the clunk of a water glass against a table, the bark of his little dog, the trilling of a telephone, the laugh of passersby. All that noise gives him physical pain. But even in his waking hours, he seems to resist speech. That’s part of the reason for his crumbling marriage: even when he’s deeply hurt, he doesn’t want to talk about it.

It's certainly rare for a foreign film featuring foreign stars to nab the Oscar for Best Pictures. But The Artist of course doesn’t need to be relegated to the Best Foreign Language Film category. Its lack of audible speech makes it universal, and its visible love for old Hollywood makes it endearing..

:

October 14, 2022

Fishing for Memories of Angela Lansbury

Most people today seem to remember the late Angela Lansbury for small-town sleuthing in TV’s Murder, She Wrote,or for playing the voice of a teapot in Disney’s Beauty and the Beast. Wonderful credits, to be sure. But there was so much more to a career that began with a 1944 thriller, Gaslight, when she was a mere 19 years old. As a housemaid named Nancy, who may possibly be up to no good, she earned her first Oscar nomination as Best Supporting Actress.

I didn’t see Gaslight until years after it came out. My first memory of Lansbury on screen comes from a 1955 Danny Kaye comedy classic, The Court Jester, in which she played a pouty princess opposite Kaye’s inept rebel masquerading as a performer at the royal court. Glynis Johns was featured too, as Kaye’s girl-of-the-people love interest. I remember how as a small child I was confused: the princess (blonde) was much less appealing to me than the peasant (Johns), but I labored under the assumption that blondes like Lansbury were usually considered more beautiful than their brunette rivals. (I had spent considerable time at my local bakery, eyeing all the blonde bride cake-toppers, standing next to their dark-haired grooms, so I was hyper-sensitive about my own dark coloring.) The fact remained that Lansbury was never, not even as a very young woman, considered a Hollywood beauty. There was something strong and tough about her—something not particularly youthful—that marked even her earliest appearances and helped her to blossom as an older performer.

Curiously, she played matronly roles (like that of Elvis Presley’s mother in Blue Hawaii) when she was only 36. One year later, she took on one of her most iconic portrayals, that of Laurence Harvey’s menacing mom in the 1962 political thriller, The Manchuria Candidate. This film led to her third supporting actress Oscar nomination: she never won, but received an honorary Oscar in 2014, in tribute to her long and distinguished career.

And she could sing too, as she revealed while nabbing 4 Tony awards (starting in 1966) for her star turns in Broadway musicals. The first was for Mame, in which she played to perfection a wealthy and flamboyant bohemian. But I saw her on the stage, for the first time, as Gypsy Rose Lee’s self-obsessed Tiger Mom in Gypsy, a performance that haunts me to this day. (It was during the intermission for Gypsythat I briefly met Groucho Marx, but that’s a story for another time.) In 1979, Lansbury possibly topped herself by creating the role of the jovial, blood-thirsty Mrs. Lovett in Sondheim’s masterful Sweeney Todd. Never has a thoroughly gruesome story been more fun. I can still see her Grand Guignol makeup, and hear her cajoling her partner in gastronomic crime to try a little priest. (This was surely a portrayal to relish!)

After these towering roles, the shrewd but amiable Jessica Fletcher of Murder, She Wrote and the sweetly sentimental Mrs. Potts of Beauty and the Beast must have seemed downright relaxing. But they allowed her to move into old age comfortably, while still continuing to work. (Her last film appearance was released this very year. She had a small role as herself in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery at the age of 96.) From all appearances, she was a Hollywood treasure, but also a human being. One day some years back, at Santa Monica’s best fish emporium, I saw her shopping for dinner. (But I don’t remember the counterman urging her to try a little plaice . . . or a nice monkfish filet.)

October 11, 2022

Baz Luhrmann Brushes Up on His Shakespeare with “Romeo + Juliet”

When I was college-age and in love, the movie to see was Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 adaptation of William Shakespeare’s timeless tragedy, Romeo and Juliet. The art direction was lush; the secret lovers were gorgeously young (Leonard Whiting was 17 and Olivia Hussey a mere 15); the cinematography and musical score were swoon-worthy. Though the screen showed us a convincing depiction of Old Verona (as well as young bodies), we could surely identify with the social concerns of these lovers and this timeframe. In the Zeffirelli film, dying for love seemed both sad and inspiring, especially for those at the right age to discover love, and sex, and the burdens of family obligations, and the rules that govern a community.

Somewhere along the line, I watched the most admired screen Romeo and Juliet of my parents’ era. That would be an MGM spectacular, directed by George Cukor in 1936. This elegant but stodgy black & white rendering of the immortal love story featured Leslie Howard (age 43) and Norma Shearer (age 36) as the “young” lovers: Shearer was the much-adored wife of producer Irving Thalberg, whose pet project this had long been. Roadshow screenings of this extravaganza sold elaborate program booklets, and ads of the era touted the Howard/Shearer paring as a repeat of their romantic chemistry in a popular melodrama called Smilin’ Through. There’s no way that my peers and I could have connected with Howard and Shearer. But the virile young Whiting and the gloriously delicate Hussey were to us completely captivating. (I’ve talked to men of my generation who first discovered, on watching the bridal-bed scene, that their tastes ran more to Romeo than to his fair young bride.)

I suppose every era must have its own Romeo and Juliet. In 1996, along came Australian filmmaker Baz Luhrmann, fresh off the success of an outrageous little dance movie, Strictly Ballroom (1992). It was a gigantic jump from a Down Under production full of no-name ballroom dance aficionados to a major Hollywood release, but Luhrmann clearly enjoys the bursting of boundaries. He brought with him the concept of a Romeo and Juliet set not in a musty Italian city but rather in a gaudy neverland named Verona Beach. His rival Montagues and Capulets are gangs of punk rockers and Hawaiian-shirted bros, brawling in the service of the adult gangster-types who run things. There are guns, cigarettes, tattoos, and swimming pools, along with a flamboyant Catholicism when religion is required. In defiance of the “whites only” classical productions of Shakespeare, here actors come in many colors, John Leguizamo swaggers through the role of Tybalt, and Juliet’s nurse has an unmistakable Latino accent But somehow the language of Shakespeare holds, though the Bard’s verbal formalities are often used ironically.

What of the central love story? Luhrmann certainly chose well. His Romeo is a baby-faced twenty-two-year-old Leonardo DiCaprio, speaking eloquently while looking really cute. Opposite him is Clare Danes, age 17, as earnest and wide-eyed as a Juliet can be. Though some of their scenes together take on a surreal quality because of their location (part of the dialogue from the famous balcony scene is played in a fabulous swimming pool), young love is definitely in the air. (The word is that Danes developed a genuine crush on DiCaprio, who wasn’t interested—so much for youthful ardor.) I’m not sure I can forgive Luhrmann for tweaking some details of the play’s ending. At any rate, high school teachers reportedly adore this version because it speaks so vividly to their students. And I can hardly complain about that.

October 7, 2022

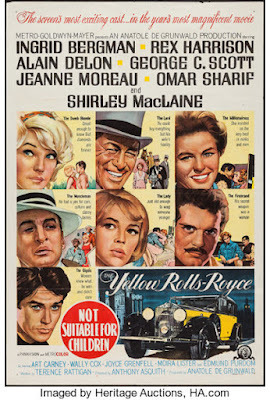

We All Ride in a Yellow Rolls-Royce

“They don’t make them like this anymore!” – That’s the tag line on the DVD box containing a splashy British film from 1964. The posters from the era proclaim, “The season’s most exciting cast . . . in the year’s most magnificent movie.” Well, no. Though the international cast is full of big names, excitement is definitely lacking. But The Yellow Rolls-Royce is a great example of how, in the advent of television, movie folk were desperate to use spectacle as a way to separate the big screen from the little ones in people’s living rooms.

The Yellow Rolls-Royce, written by famed British dramatist Terence Rattigan (Separate Tables) and directed by Anthony Asquith, is one of those compilation films that try to yoke together separate tales set in different locations and time frames by means of some sort of linking device. (A more recent example: 1998’s rather lugubrious The Red Violin). Here it’s a 1931 stretch limo, in gaudy yellow and black, that passes from owner to owner, from country to country. The real star of the film is undoubtedly that magnificent car, first seen being secretly conveyed through the streets of London to a posh dealership. There it’s spotted by a veddy wealthy British aristocrat (Rex Harrison), who quibbles about the placement of its back-seat telephone, but snaps it up as an anniversary gift for his beloved wife.

What he doesn’t know is that this wife (a young Jeanne Moreau), having tired of life among the British swells, has found herself a handsome young functionary with whom to canoodle. Naturally, the yellow Rolls-Royce plays a role in their assignations. (It has roll-down window shades that come in very handy under the circumstances.) There’s a mournful, but by no means tragic, ending to their story, at which point the car is quickly returned to the dealer.

After the bittersweet tone of Story #1, we move on to Italy, where after many presumed adventures with owners from diverse lands, the Rolls is acquired in Genoa by a Miami mobster played by the unlikely George C. Scott, who seems to be having a ball speaking in demsand doses. His sidekick is the always welcome Art Carney, and his blonde-bimbo fiancée is none other than Shirley MacLaine. She falls for street photographer/gigolo-in-training Alain Delon, but ultimately recognizes on which side her focaccia is buttered. Of course the Rolls figures into the story.

Story #3 plays out in 1941, on the border between Trieste and Yugoslavia. A mega-wealthy and mega-powerful American, played by Ingrid Bergman, buys the yellow Rolls, although it has clearly seen better days. Determined to motor into Yugoslavia to visit her friend the president, she blithely ignores the very real threat of a Nazi takeover. At first she seems tragically naïve, but when a Yugoslav partisan (Omar Sharif) begs her to transport him back to his country in the boot of the Rolls, she blossoms into a fierce defender of Yugoslav freedom.—and into the earnest, patriotic Bergman we know and love from films like Casablanca.

This third segment definitely has the most meat to it; it’s also the only one of the tales in which a central character grows and changes. Otherwise, these are mostly interesting stories that didn’t much capture the hearts of the viewing public. The whole impetus for the Yellow Rolls-Royce was The VIPs, a highly successful all-star film from the same production team. That flick, set at Heathrow Airport, featured Taylor and Burton at the height of their celebrity, along with Maggie Smith, Orson Welles, and others. But not, I believe, a single Rolls-Royce.

October 4, 2022

Dancing Down Memory Lane with Zorba the Greek

In 1964, the cool kids discovered Greece. Greek line-dancing was taught to enthusiastic hipsters at folkdance cafés across the country. Souvlaki was the snack of choice, and ouzo became a favored tipple. Everyone (even Joni Mitchell) wanted to go camp out on a lonely beach on some Greek isle. Why this passion for all things Hellenic? Chalk it up to the outsized success of a small film, Zorba the Greek.

Zorba The Greek was directed by Michael Cacoyannis, a talented Cypriot who launched his career with works performed in Greek. In 1962 I first encountered his Electra, adapted from the classical text of Euripides, and I still remember its raw power. Years later I marveled at how he could people The Trojan Women with some of the world’s brightest international stars (Katharine Hepburn, Vanessa Redgrave, Genevieve Bujold, Irene Papas as Helen of Troy), set them against the rugged Greek landscape, and vividly convey what Euripides’ anti-war tragedy was all about.

I was an arty kid, willing to read subtitles and open to watching the playing out of a text that dates back to 415 BC. Admittedly, not everyone in my generation had my arcane tastes. But we all found it easy to adore Zorba the Greek, a film full of love and laughter, at the same time that it explored in heart-wrenching detail the tragedies of life. Adapted by Cacoyannis from a well-loved novel by Nikos Kazantzakis, a nine-time nominee for the Nobel Prize for literature, the film gave Hollywood’s Anthony Quinn (who also produced) his most iconic role. He’s a marvel as a man who functions as a life-force: passionate, roguish, someone who fights off tears by dancing his heart out on the sands of Crete.

Quinn’s opposite number in the film is Alan Bates as Basil, the strait-laced young Englishman who must be taught to laugh at fate. Then there’s Lila Kedrova, who picked up an Oscar for her portrayal of a vulnerable Frenchwoman, the keeper of a shabby hotel in a small Greek village, The final main character, played by Cacoyannis favorite Irene Papas, is known only as The Widow. Her essentially non-speaking role calls forth all her beauty and dignity. She’s the solitary young woman, clad in black from head to toe, who moves silently through the town, hated by all the local wives, lusted after by their husbands. It’s clear enough to all of us that something dreadful is about to happen.

As viewers, we never find out anything about the Widow, nor what became of her husband. In a sense, we in the audience are in the same position as Alan Bates’ character: we’re outsiders, learning about a culture we don’t entirely understand. Though the movie contains some brief conversations in subtitled Greek, mostly it’s in English, spoken by characters (like Basil, like Kedrova’s Madame Hortense, even like Zorba himself) who are not genuinely part of the local scene. In a film that acknowledges a language barrier as one of the things that separate people from one another, visuals are particularly important. And so they are here. The Oscar-winning black & white camerawork of Walter Lassally graphically highlights the stark drama that’s part of this town’s life. One moment I particularly recall captures the moments immediately following the death of Madame Hortense. The elderly crones of the neighborhood, all clad in widow’s weeds, steal into the bedchamber where her illness-wracked body still lies. Like the harpies in classical tales, they silently make off with every trinket she owns, leaving her room stripped bare..

Then of course there’s Mikis Thedorakis’ evocative, dance-worthy score. Opa!

September 30, 2022

Running Wild with Jonathan Demme and Friends

Ever since the untimely death of Ray Liotta four months ago, I've been trying to get hold of Liotta’s 1986 breakout performance in Jonathan Demme’s Something Wild. Three years before he played a ghostly Shoeless Joe Jackson in Field of Dreams, four years before he went to the mattresses as Henry Hill in Goodfellas, Liotta was indelible as a former high school classmate of Melanie Griffith’s Lulu, a man with a hair-trigger temper and a great enjoyment for mayhem. He must have made quite an impression on my fellow movie-lovers. When—after his death at age 67--I started requesting the film from my local library, it took four months for it to end up in my DVD player.

It was worth the wait. After Hours, shot by Demme in 1986, is described online as an “action comedy.” But that designation doesn’t begin to suggest the film’s antic impact. At first it’s indeed very funny, showing a Wall Street financial nerd (Jeff Daniels) who can boast a big and very recent promotion falling under the spell of a gaudily-dressed party girl, played by Melanie Griffith (she of the babyish voice and the body that just won’t quit). This mismatched pair embarks on suburban adventures that feature alcohol, handcuffs, reckless driving, and thrill-seeking of all varieties. But just when we’re thoroughly enjoying their unlikely fling, the tone of the movie starts to shift dramatically. Griffith’s Lulu is not quite the carefree gal she seems to be, nor is Daniels’ uptight yuppie entirely telling the truth about his own placid homelife. And then there’s Liotta, showing up as Ray Sinclair at Lulu’s Pennsylvania high school reunion. Ray is handsome, charismatic, and alarmingly volatile, and when he appears the movie takes a left turn from which there’s no going back.

It was Demme’s goal, at this fairly early point in his directing career, to try to meld screwball comedy and film noir. His bold experiment with a midpoint shift in tone made me, when I first saw the film, slightly queasy. This time around, I enjoyed Demme’s directorial sleight of hand for what it was. The film is a wild ride, and its unpredictable quality—in an era when we can generally figure out what’s coming next on our movie screen—now strikes me as hugely refreshing. I don’t always agree with the late Roger Ebert, but I love his description of Something Wild: “This is one of those rare movies where the plot seems surprised at what the characters do.” Exactly right!

One of the most memorable aspects of Something Wild is the role played by Griffith’s costumes and hair stylings. Clothes, in this film, do make the man . . . or, in this case the woman. The sexy vagabond of the early scenes—with her brunette bob and her jangling jewelry—is suddenly transformed, later in the film, into a honey blonde who favors toned-down makeup and prim white frocks. Lulu’s costume changes signify the revelation of the various layers of her complicated psyche. There’s one more major costume shift at the tail-end of the film. It’s a final twist that many critics find arbitrary and not needed, and I think they’re right. But that’s the challenge of a script as eccentric as this one: knowing when to stop.

The film’s score ranges from the classic to contributions by such pop icons as Laurie Anderson and David Byrne. Unsurprisingly, the featured track is “Wild Thing,” performed in various versions. .A hip surprise is the cameo appearances by indie iconoclasts John Waters and John Sayles. They too can be considered something wild.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers