Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 28

February 14, 2023

Ana de Armas as Marilyn: Hollywood Prefers Blondes

So Cuban cutie Ana de Armas, who lit up her scenes as the nice girl in Knives Out, is now an Oscar nominee. She’s on the Best Actress list (along with superstars Cate Blanchett and Michelle Yeoh) for her portrayal of Marilyn Monroe in Blonde. With careful makeup and a platinum dye job (as well as, I suspect, a plethora of wigs), she bears an uncanny resemblance to the late glamour queen. I’m impressed with how she’s managed to erase a Latin American accent while also taking on Monroe’s distinctively breathy speech mannerisms.

As strong as her performance is, I tend to think the nomination is partly an apology to de Armas for having put up with so much. If Monroe suffered hugely from Hollywood’s propensity for exploiting young women, de Armas feels like a victim too. This film—based on a highly speculative 2000 bestseller by Joyce Carol Oates—seems a great deal less interested in Monroe’s soul than in her body. There are far more bare-breast shots here than in any Roger Corman flick I can think of. And the camera’s intimate glimpses of other parts of de Armas’s anatomy are often downright gynecological. Do we really need to see, in close-up, quite so much of Marilyn’s abortion? I suspect writer/director Andrew Dominik feels this is bold filmmaking, but to me it’s an exploitation film, pure and simple.

Though Blonde takes pains to reproduce faithfully some of Monroe’s most memorable screen moments, the focus is primarily on her private life, in which misery continually gives way to more misery. There’s little Norma Jeane’s crazily addled mother, then some not-so-nice neighbors, lecherous studio bosses, two sexually questionable sons of Hollywood who share her favors, and ultimately a parade of lovers and husbands unable to fully appreciate her. We see a jealous Joe DiMaggio (Bobby Cannavale) beat her up after eyeing her nude publicity photos, and an apparently happier union with playwright Arthur Miller (Adrien Brody) comes to an abrupt close after she suffers a miscarriage. Throughout there’s something I suspect is an Oates invention: Norma Jeane’s mysterious absentee father, sending a long string of letters to tell her he’ll be arriving soon for a much-delayed reunion.

The single most grotesque relationship she endures is with President John F. Kennedy, lounging on a hotel bed (really?) in the midst of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Naturally, at this crucial time in the nation’s history, POTUS needs to get a load off, so Secret Service goons have hustled a shaky Marilyn from Hollywood to D.C. Soon we’re treated to an extreme close-up of poor Ana de Armas apparently performing oral sex on the presidential you-know-what. I guess it works: our country is saved from nuclear war.

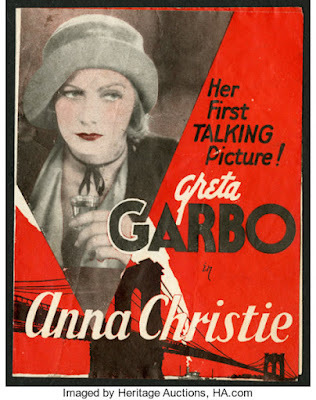

It's coincidental that I recently watched Greta Garbo in the 1930 film version of Anna Christie, a faithful adaptation of the Eugene O’Neill play about a young woman trying to leave her sordid past behind. In a 2012 documentary called Marilyn in Manhattan, the actress Ellen Burstyn recounts what she calls a “legendary” story set in the Actors Studio, where Monroe had enrolled to seriously study her craft. Apparently she joined with stage veteran Maureen Stapleton to perform a scene from the O’Neill drama. According to Burstyn, "Everybody who saw that says that it was not only the best work Marilyn ever did, it was some of the best work ever seen at Studio, and certainly the best interpretation of Anna Christie anybody ever saw. She . . .achieved real greatness in that scene." Too bad that a film honoring Monroe should be such an embarrassment.

February 10, 2023

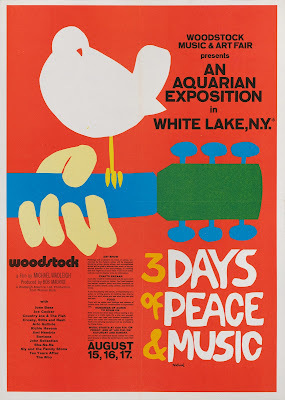

“Woodstock”: Getting Back to the Garden

The New Beverly Cinema, on Beverly Blvd. in midtown L.A., dates back to 1929, but it was not always a movie theatre. It has housed vaudeville performances, specialized in foreign films, and (when re-named The Eros) devoted itself to porn. My most memorable visit came during my grad school years when—as a fledgling film reviewer for the campus paper—I was invited to come view Japanese auteur Hiroshi Teshigahara’s somber and claustrophobic Woman in the Dunes, all by myself, in an auditorium that normally seats 300. A brilliant film, but hardly my happiest experience at the movies.

Today things are looking up for the New Beverly, which was purchased by Quentin Tarantino in 2010 in order to show old films (always in 35mm prints) that he particularly admires. Last Sunday, I was privileged to see a screening of the Oscar-winning 1970 documentary, Woodstock. Of course it commemorates the famous 1969 festival that attracted some 500,000 young people to what was billed as “3 Days of Peace & Music.”

I’d seen Woodstock when it was released in 1970, a quick nine months after the 1969 summer festival that marked a joyous farewell to the tumultuous Sixties. Now that fifty years have passed, I found myself struck once again by those youthful concert-goers who were so deeply in love with rock music, weed, sex, and their own bodies. The performance footage is memorable, including Sly Stone trying to take his listeners higher, Jimi Hendrix sneaking a mournful Taps into his apocalyptic version of “The Star Spangled Banner,” and Crosby, Stills & Nash admitting (after a masterful “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes”) that this was only their second performance as a group. Dale Bell, one of the film’s producers, has explained to me how a ring of expert photographers stationed themselves around the stage and in the light towers to capture the performers from every angle, in all their glory.

But what I’ll remember best is the documentary footage that seems to cover EVERYTHING about Woodstock: the grouchy locals, the happy hippies, a free-wheeling chat with a cheerful Port-o-San man who admits he has one kid attending the festival, and another in Vietnam. Among the many memorable moments: an attendee insisting that U.S. government forces have deliberately seeded the clouds overhead to try to rain out this parade. What’s lovely is the apparent spontaneity captured on film: young people unselfconsciously grooving to the music, slipsliding down patches of mud after that rainstorm, stripping down to bathe in local streams, tenderly making love. The sound team captures a marriage proposal over the P.A. system, and announces the birth of a baby. (No telling how many babies were conceived at Yasgur’s farm over three days and nights.)

Dale Bell has authored or edited several related books, including Woodstock: An Inside Look at the Movie that Shook Up the World and Defined a Generation. He readily cites moments from the film, and is happy to quote co-founder Michael Lang on why the festival still resonates in the collective consciousness: “It’s the music. It’s the lyric. It’s the being together.” After a long career that spans public television and documentary film, Bell is returning to his first love with a podcast he plans to call “Woodstock Matters.” Fifty-four years after the crowds dispersed, he wants to probe the festival’s (and the film’s) longterm impact: “I want to sprinkle water on it again, and see what grows.” His first guest? Musician and photographer Henry Diltz, recently honored at the Grammy Awards for his portraits of rock royalty.

February 7, 2023

“Anna Christie”: Back When Actors Had Faces

As awards season heats up, with this year’s Oscars slated to be handed out on March 12, it’s hard to believe that Academy Awards were first presented in 1929, when most movies had not yet learned to speak. The November 1930 ceremony, a swanky shindig held at L.A.’s Ambassador Hotel, gave its biggest prize to the Hollywood adaptation of an anti-war classic, Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front. Amazingly, one of ten films in the running for Best Picture of 2022 is the first-ever German language version of this same “war is hell” novel.

At the 1930 ceremony in which All Quiet on the Western Front won its laurels, Greta Garbo’s name was very much in evidence: she competed against herself in Anna Christie and something called Romance. (Norma Shearer took home the statuette.) Anna Christie was also singled out for its direction (by Clarence Brown) and its cinematography (by William H. Daniels, an ace who was still earning nominations in 1964). Daniels’ intimate black-&-white camerawork is one of the glories of Anna Christie, in which the screen is filled with enormous close-ups of some of Hollywood’s most expressive actors. Daniels, of course, had learned his craft in the silent era, and he thoroughly understood Norma Desmond’s rueful remark in Sunset Boulevard: “We didn’t need dialogue. We had faces.”

In Anna Christie there are both faces AND dialogue. The most dramatic face, of course, belongs to that scintillating Swede, Greta Garbo, who can be mesmerizing whether she’s projecting world-weariness or joy. Then there’s the beautifully ugly Marie Dressler, as well as George F. Marion as Garbo’s long-estranged father, a frequently tipsy sailor who speaks ominously (and with a colorful Swedish accent) about the allure of “dat Old Debbil Sea.” Both the gritty oceanfront environment and the generally foreboding atmosphere mark this as a play by Eugene O’Neill, who won his second Pulitzer for this early work back in 1922. It's a simple story, but a poignant one. In a rundown wharf-side tavern, Old Chris (Marion) gets word that his twenty-year-old daughter is leaving Minnesota to come stay with him. He fantasizes that she’s a healthy, hearty farm gal, but when she arrives it’s clear that life has been hard on her. Because this was Garbo’s first talkie, Anna Christie was marketed with the slogan “Garbo Talks!” So I’m sure there was some suspense as to what her voice would sound like and what she would say. Spoiler alert: her very first line, after she slumps into the bar-room with a suitcase in tow, is this: “Gimme a whisky, ginger ale on the side, and don't be stingy, baby!"

Though Old Chris remains blind to his daughter’s travails back home, it’s quickly clear to the audience that Anna has faced her own rough seas. She hints at abuse by a family member, and it’s obvious that her “job” in the Twin Cities involved prostitution. Still, she forges a relationship with Old Chris, and they manage to live with some contentment on the coal barge of which he’s now captain and crew. But when they rescue some sailors adrift on the open sea, love comes into the picture., and Anna is challenged to open her heart to the possibility of happily-ever-after. Far be it from me to give away O’Neill’s ending.

Trivia time: There’s a second Garbo version of Anna Christie, shot in German with a largely different cast for the European audience. (“Garbo spricht Deutsch!”) A 2018 opera exists too. And, remarkably, in 1957 the play was turned into a Broadway musical, innocuously called New Girl in Town.

February 3, 2023

Navigating “Triangle of Sadness”

I’m told that among fashion-forward folk, the “triangle of sadness” is the area between one’s eyebrows and the top of one’s nose bridge, the space in which wrinkles related to ageing and unhappiness tend to congregate. (Purveyors of Botox, of course, are delighted to help you rejuvenate yourself by plumping out this region.) I had never encountered the term “triangle of sadness” before watching a darkly comedic English-language film that carried off the Palme d’Or at last year’s Cannes Film Festival. Because the film opens with a line-up of buff male models all vying for a lucrative gig, it makes sense that the ominous “triangle of sadness” gets a quick mention. I should add that there are other possible meanings for the phrase as well. Since the main action unfolds on a luxury cruise ship whose voyage goes awry, it’s fair to think of the infamous, mysterious Bermuda Triangle, the graveyard of many a sea-going vessel. And the film contains, if you look at it geometrically, a perverse sort of love-triangle as well.

I had vaguely heard of Triangle of Sadness when it was first released, but last week’s 2023 Oscar nominations made me sit up and pay attention. Not only is this small film in the running for Best Picture (along with Avatar 2, The Fabelmans, and Everything Everywhere All at Once) but its Swedish director, Ruben Östlund, is one of only 6 candidates for Best Director, in the august company of Steven Spielberg (The Fabelmans), Martin McDonagh (The Banshees of Inisherin), Todd Field (Tár), and the two Daniels whose teeming brains concocted Everything Everywhere. Östlund is also up against the same men (yes, they’re all men) in the tough original-screenplay category. Clearly, some Academy members were extremely impressed.

I’m not sure whether it’s just coincidental, but the shipwreck aspect of Triangle of Sadness reminds me a lot of a popular 1902 stage play by none other than J. M. Barrie, author of Peter Pan. It’s been a long while since I read The Admirable Crichton, but the gist of Barrie’s comedy is that is that when some very upper-crust Britishers are stranded on a tropical island, the one traveler with some practical skills upends the traditional social hierarchy and becomes the man in charge. There’s a mild social message here, and a considerably tougher one in Triangle of Sadness, in which an American ship’s captain with Marxist leanings (Woody Harrelson, as you’ve never before seen him) debates political theory with a wealthy Russian oligarch while a storm rages outside. It’s all meant to seem absurdist in the extreme: while the hard-working crew members desperately strive to keep the posh passengers happy and safe, Harrelson’s captain remains focused on his political rejection of the opulent lifestyles all around him.

I don’t think it’s accidental: “Screw the rich” seems to have become a major theme in recent years. In addition to Triangle of Sadness, see also Knives Out, Glass Onion, and elements of Elvis, Blonde, and She Said.. Then there are, of course, both seasons of TV’s White Lotus, in which the wealthy and entitled show up at a super-exclusive resort, and bad behavior ensues. Truth be told, we like to be persuaded, as F. Scott Fitzgerald would have it, that the rich are very different from you and me. But—as someone close to me has pointed out—without the ultra- rich you can’t make movies. For the deep-pockets financiers behind these projects, in which the very wealthy are confirmed to be selfish and cruel, is this a matter of self-flagellation? Somehow I think not.

January 31, 2023

Does Father Know Best?: “Aftersun” and “Armageddon Time”

Aftersun? I admit I felt an after-shock, once I checked the rave reviews for an art-house film full of weird camera angles, scratchy footage, and little to no plot. Yes, it can be interesting to pan through someone’s vacation videos, looking for clues about relationships and impending traumas. But Aftershock just didn’t seem as fascinating to me as it did to my favorite serious critics, who pronounced it a work of genius by a bright new filmmaker, Charlotte Wells.

Maybe it’s all a matter of watching an ambitious film on a theatre-sized screen. Maybe you need to be in the right place (and not on your living-room couch) to appreciate idiosyncratic artistic choices and stories that hide the characters’ motivations beneath scads of mundane details.

Yes, I was sympathetic to a film about the relationship between a lively 11-year-old girl and her 30-year-old father making up for lost time at a vacation resort. I could see the inherent tensions between them: the dad’s efforts to shield his daughter from his cigarette cravings, his tentative inquiries about her mother back home, the daughter’s budding fascination with the teen-age canoodling going on around her. But the critics’ glib explanation that this is a memory piece, with the now-grown daughter trying to sort through her recollections of a father who has come to a bad end, led me to wonder how they’d sorted out the film’s few clues and come to such a definitive explanation. (Question: was it all laid out for them in the film’s press packet?) I like sleuthing beneath the surface as much as the next moviegoer, but my main feeling here was one of frustration.

Speaking of fathers, I’ve also just watched James Gray’s semi-autobiographical Armageddon Time, in which a middle-class New York kid discovers that life is not always fair, that when it comes to trouble his African-American buddy will always be getting the short end of the stick. Most reviews I’ve seen have focused on the story’s racial elements, as well as the kid’s deep emotional connection with an old-world Jewish grandfather who knows from discrimination. That grandfather is played by Anthony Hopkins, in an unlikely but surprisingly convincing piece of casting. But Gray’s well-realized story also draws sharp portraits of young Paul Graff’s parents.

It is striking to see Anne Hathaway, so often a perky ingenue, play (very nicely) a mom, one who’s trying awfully hard to hold together a family group whose values sometime conflict with one another. But I found myself particularly interested in Jeremy Strong, an actor whose name is new to me, despite his impressive stage and screen credits. (He won an Emmy for Succession And, with a lot more hair, he was Jerry Rubin in 2020’s The Trail of the Chicago 7.) Strong plays Paul’s father, a plumber who has married into an affluent family, but can never quite forget his own blue-collar roots. What makes him so fascinating—and so real—is that he’s a volatile man, who reveals different sides of his personality at different moments. Waking up his son for school on an ordinary morning, he's charmingly goofy. When there’s just been an overnight death in the family, he’s gentle. But when Paul is accused of serious wrongdoing at school, he responds with a towering fury that is just shy of dangerous. What we don’t quite realize immediately is that he feels himself a bit of an outcast in this family. He’s not comfortable with the burden of private school tuition for both of his sons. Here’s a father who’s complicated, but the clues aren’t hard to fi

January 26, 2023

Everything Everywhere . . . and the Kitchen Sink

The last time I saw a movie about the running of a laundromat, it was My Beautiful Laundrette. That 1985 British dramedy, an early film for both director Stephen Frears and actor Daniel Day-Lewis, had a lot to say about social relationships, particularly those involving culture clashes between native-born Londoners and immigrants from Pakistan. Everything Everywhere All At Once is also about immigrants who own a laundromat, but social realism is not exactly its genre. This hugely popular film, which now leads the pack with 11 Oscar nominations, somehow combines an intimate family story with a bravura tale about saving the universe by way of martial arts derring-do.

Everything Everywhere starts out matter-of-factly enough, with a frazzled Chinese immigrant named Evelyn Wang, played by the wonderful Michelle Yeoh. Evelyn is stressing about everything in her life: the state of the family laundromat, an obligatory birthday party for her ancient father (94-year-old movie veteran James Hong), her boyishly naïve husband (Ke Huy Quan, who once played a nerdy kid in The Goonies), and the fact that her daughter Joy (Stephanie Hsu) is in love with another woman. And then there are tax problems which require the family to meet with a mousy but stern IRS agent (Jamie Lee Curtis, having an absolute ball playing against type). It’s right in the middle of a tense meeting at IRS headquarters that Yeoh’s character discovers that the universe operates on multiple levels, and that she’s personally in charge of saving the world from evil. Say what? She’s not convinced, but suddenly her amiable husband is making impressive martial arts moves, using his dad-sized fanny pack as a weapon of war.

From this point onward it’s a wild ride through the cosmos, with Evelyn alternatively overjoyed and terrified by her multiple selves, which include a woman warrior, a Chinese opera star, and glamorous movie queen. Yes, in her long Chinese film career, Michelle Yeoh proved she could be convincing as all of these things. I was surprised to learn that the film script for Everything Everywhere was retooled for her benefit; it was originally supposed to star Jackie Chan. But the male-to-female transition of the leading role allowed writer/directors Dan Kwan and Daniel Scheinert to explore a woman’s role both in a kung fu-style universe and in a domestic household, thereby giving their admittedly wild and crazy story some spine.

Of course, not everyone has been a fan. Though film critics and chopsocky enthusiasts (not to mention members of the Academy) have shown their adoration for this highly original and skillfully produced entertainment, it can be hard for some of the rest of us to get with the program. I suspect there’s a huge generational divide involved: someone with whom I watched this film on my brand-new giant TV screen had a hard time finding any dramatic point at all within the film’s fun and games. (It does exist, I promise, but you may get restless—over a stretch of 2 hours and 19 minutes—while wading through bagel jokes, lightning-fast montages, and goofy parodies of other flicks in order to find some actual meaning at the story’s end.) The film can be seen as a bold homage to the entire history of cinema. Or the entire history of pop culture. Or something like that. I do know, though, that my movie-viewing partner just came away from this experience feeling old and tired. Personally, though I love the artistic boldness that went into this concept, I know exactly what he means.

To Bernie—many happy cosmic returns!

January 24, 2023

Catherine Cyran: Force of Nature

This year had barely started when I was shocked by an item that appeared in several Hollywood trade publications. The headlines read “Catherine Cyran, Emmy-Nominated Director, Dies at 59.” It turns out there were several errors in these stories (for one thing, Cyran made it to her sixtieth birthday), but the basic facts were all too true. The vibrant young woman with whom I had worked closely at Roger Corman’s Concorde-New Horizons had been carried off by cancer, after two years of valiant struggle. From my perspective, at least, it all began in the 1990s, when Catherine moved into an office next door to mine. She had been recommended to Roger by a fellow Harvard graduate. Roger, always impressed by Ivy League credentials, doubtless also liked hearing that she’d spent some time in the business school of his own alma mater, Stanford. Nonetheless, she started off in a modest job as assistant to the two women in charge of distribution. Catherine being Catherine, she didn’t stay behind that desk for long.. It helped that Roger appreciated strong women, and enjoyed promoting them into positions of power. (Producer Gale Anne Hurd, who would go on to launch her own big-league career with The Terminator, is only one of the Corman alumnae who insist that Roger preferred hiring women because they were smarter, worked cheaper, and were more loyal.) As Catherine’s role at Concorde grew, she and I spent some time trying to work out the plot for a martial arts movie, to feature our in-house kickboxing star, Don “The Dragon” Wilson. When I discovered that back at her New York high school Catherine had been a top--rank violinist (who knew?), we came up with the notion that our hero would be torn between his budding kickboxing career and his love for the violin. Yes, in retrospect it sounds like a bad mash-up of old John Garfield movies, but plotting it out was fun. Later, when Roger’s wife Julie Corman bought the rights to a Middle Grade adventure classic called Hatchet, the three of us talked at length about exactly how to adapt it for the screen. Once all the details were ironed out, I noted that someone would have to do the actual writing of the script. Catherine quickly volunteered, and A Cry in the Wild became a notable success. (The title was changed from Hatchet, because anything connected with the Corman name would probably be mistaken for a horror flick.) Once Catherine earned that first screen credit, her ambitions grew. She wrote a second wilderness adventure that took advantage of her own outdoor skills, and then directed it herself. White Wolves nabbed her an Emmy nomination for outstanding direction in a children’s special, and she was well on her way.

Since those long-ago days, Catherine’s résumé has grown to include 15 films as a writer, 18 as a director, and 8 as a producer. Along with family films like The Prince & Me II: The Royal Wedding, she’s made erotic thrillers and delved into the horror genre. Notably, she wrote Werewolf: The Beast Among Us (2012), to be directed by her longtime life partner, Louis Morneau. Last September, while battling Stage 4 cancer, she rallied to direct Our Italian Christmas Memories, which aired in November on the Hallmark Channel. Louis told me, “It's a very nice final film which deals with Alzheimer's. She was very proud of it, her mother having died from the disease. We are hoping Beau Bridges receives an Emmy nomination.”

As Roger Corman knew, a strong woman can do just about anything.

January 20, 2023

Tuning in to the White Noise

My online dictionary explains the phrase “white noise” as “a steady, unvarying, unobtrusive sound, [such] as an electronically produced drone or the sound of rain, used to mask or obliterate unwanted sounds.” White Noise is also the name of a new Netflix film by Noah Baumbach, based on a 1985 Dom DeLillo novel. The talented Baumbach, known as the writer/director of such quirky but highly emotional films as 2006’s The Squid and the Whale and 2019’s Marriage Story, here works at capturing DeLillo’s darkly comic sensibility, the better to convey the absurdity of everyday life.

It’s not often that what sticks in your mind at the end of a film is the footage under the closing credits. Though White Noise, in re-creating 1980s suburbia, frequently sets scenes in the aisles of the gleaming local supermarket, I wouldn’t have guessed that this is where we would end up at the final fadeout. After all, the story has big things on its mind, like academic rivalries, an “airborne toxic event” leading to mass evacuations, covert drug use, betrayal, and even attempted murder. But when push comes to shove, everyone has to eat, right? And—as the credits roll—the well-behaved shoppers at the local A&P (product placement is rife in White Noise) suddenly begin to dance, lofting rolls of toilet paper, exuberantly tossing plastic bags in the air, engaging a fellow cart-pusher in an exuberant pas de deux in the produce aisle.

The first thing you notice as the film begins is the clamor and the clatter of everyday speech, which permeates the household of Jack Gidney. He’s played by Baumbach stalwart Adam Driver, who is here dressed and made up to look as paunchy and unattractively middle-aged as possible. Baumbach doesn’t play favorites; his longtime partner, Greta Gerwig, takes the role of Jack’s wife, and she too is shot to look frazzled and angst-ridden. Part of the tension stems from their complicated family life: Jack has been married four times, and the four kids who help make up the teeming household are generally at odds, partly because although each of them comes from a different relationship, they are all expected to meld into a convivial family unit. And so they do—at times, such as when that mysterious toxic event forces them out into the potentially lethal countryside.

Meanwhile, Jack is troubled by his wife’s mysterious behavior, and even by his own career choices. As the world’s leading authority on Hitler Studies, he’s trying not to own up the fact that he knows no German. And then there’s Murray, his campus frenemy (Don Cheadle), who envies Jack’s fame and would like to be receiving similar recognition for his own Elvis Studies expertise. Will Jack’s dramatic appearance in front of Murray’s students help lift Murray’s campus prestige? Or will it destroy any ties of friendship between two ambitious iconoclasts? Do we care? Maybe not, but Baumbach’s overall aim is to point up the ridiculousness of their goals.

If you like tightly-structured films that head inexorably in one direction, building at last to a powerful conclusion, White Noise is not for you. This film meanders from place to place, ricocheting between ideas and styles. Some critics have applauded; others have not been charmed. I like a comment from David Ehrlich of IndieWire who called the results of Baumbach’s work here “equal parts inspired and exasperating.” Personally, I miss both the sweetness and the character complexity of Marriage Story. But White Noise is provocative and definitely not dull. And it has made me look at my local supermarket in an entirely new way.

January 17, 2023

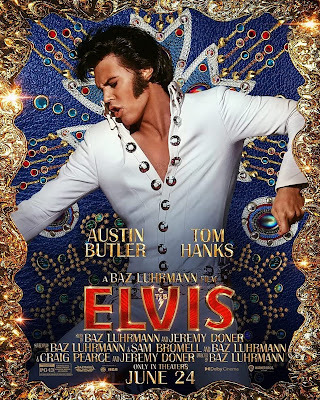

Before Elvis Left the Building

Last Thursday, the day I learned of the death of Lisa Marie Presley at age 54, seemed the right time to finally check out Baz Luhrmann’s biopic of Lisa Marie’s daddy. Of course I mean Elvis, who was born in 1935 in Tupelo, Mississippi and succumbed to cardiac arrest in Memphis, Tennessee in 1977, at the not-so-ripe old age of 42. In life, Elvis—who upended the music world by injecting African-American rhythm and blues into Top Forties pop, then adding in an outrageously kinetic performance style—was credited with transforming rock n’ roll into something essential to teenage life. His flamboyance and Luhrmann’s often over-the-top brand of filmmaking would seem to be a perfect match.

My feelings for Luhrmann as a film director have always been mixed. Back in 1992 I was entranced by his charmingly outrageous Australian debut film, Strictly Ballroom. Once he went Hollywood, I found things to like in both Romeo + Juliet and Moulin Rouge!, notably a hugely expressive visual style. Still, Luhrmann’s tendency to overwhelm his stories with lurid art direction and camera tricks was hardly to my taste. But I wondered if, with a born showman like Elvis Presley, he’d finally discovered his perfect subject.

Luhrmann’s choice to frame Elvis’s story by using his longtime manager, Colonel Tom Parker, as its narrator also sounded provocative. Parker, something of an international man of mystery, concealed his Dutch roots and his lack of official American papers as he promoted some of country music’s rising stars. Upon discovering Elvis, he became a shifty father figure, influencing the star’s personal life as well as his career. Though the all-American Tom Hanks would seem to be an odd choice for the role of Parker, I thoroughly enjoyed the film’s early scenes, in which razzle-dazzle filmmaking whisks us from one concert venue to another, underscoring Elvis’s intense visceral effect on his female fans. There’s a carnival quality to these scenes, connecting with the fact of Colonel. Parker’s longtime familiarity with carny acts and sideshow spectacles, that struck me as distinctive and important.

Actually, my favorite section in the entire film does not even include Austin Butler’s much-hailed performance in the title role. Its focus is the very young Elvis, a poor country boy perhaps 8 years old. Hanging out with a horde of African American cronies, he happens upon a Black juke joint where hot music and steamy sensuality are the order of the day. In his wanderings, he also discovers a Black revival meeting, where he’s entranced by the writhing of newly-saved souls. These formative encounters, conveyed to us via strong visuals, are what Luhrmann suggests have eventually shaped the mature Elvis’s personal style. And this notion is passed on to us in the audience by way of Parker’s narration..

At a certain point, though, the notion of Parker as a Mephistophelean narrator and commentator wears thin, and Tom Hanks, with his weird (though apparently authentic) accent, has less and less to do in this story. As we move into Elvis’s private life, spending time in situations of which Parker would seem to have little knowledge, Elvis devolves into that very standardized thing, a biopic. Which means we see Elvis, having reached the pinnacle of his fame and fortune, struggling with his past, with his marriage, with his rapidly degrading sense of self. Ho hum. After a while, all biopics start to look alike. Childhood trauma, then the heart-pounding rise to stardom, then the long, sordid slide into desolation and decay. Why, really, do we bother? It always ends the same way.

.

January 13, 2023

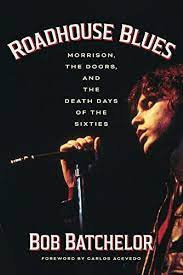

The Next Whiskey Bar: Jim Morrison and “The Doors”

Back in 2008 I had a long, deep conversation with one of my personal music heroes, Ray Manzarek. Yes, Ray was the keyboard master who did amazing things on an orgasmic 1967 rock hit, “Light My Fire.” A natural leader, Ray in 1965 (then fresh out of UCLA’s film school) encouraged a shy young poet named Jim Morrison to become the lead singer of a new L.A. band called The Doors. It wasn’t long before the four Doors (having, in Manzarek’s words to me, used psychedelics to “open the gates of perception”) found world-wide fame. But Morrison’s excesses became notorious, up until his untimely death in Paris in 1971, at the age of 27.

Like everyone else, Manzarek was stunned by Morrison’s mysterious demise. Of course he knew that Jim was—thanks to a steady diet of drugs and booze—rapidly going downhill. But he figured that Paris would provide the needed antidote, that this was Jim’s chance to recalibrate himself. As Ray told me, he foresaw Morrison turning into “an American in Paris, a poet, an American poet. He was gonna be the next in line: F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Henry Miller, Jim Morrison—that’s what I saw happening. He was gonna go to Paris and rejuvenate himself, and start to write again, not be a rock star but go back to being the poet that he was when we put the band together back in 1965.”

Of course that’s not what happened, and Morrison’s heart attack in a Paris apartment bathtub became an essential part of the legend. It provided a dramatic conclusion for the biographical film released by writer-director Oliver Stone in 1991, with Val Kilmer playing the Morrison role. The Doors turned out to be only a middling success, with most of the praise going to Kilmer’s all-in performance. Watching it for the first time recently, I found myself frankly bored by the endless scenes of Jim’s bad behavior. In a new book, Roadhouse Blues (subtitled Morrison, The Doors, and the Death Days of the Sixties) pop-culture scholar Bob Batchelor weighs in on the film’s omissions, partly by citing the words of Jim’s former bandmates. He quotes at length guitarist Robby Krieger, who gripes that in Stone’s film Morrison comes off as “a pretentious, obnoxious, stupid drunk who was a dick to everyone around him.” While admitting that Jim could be difficult at times, Krieger points out that “he was funny, and shy, and when he was out of line he knew it, and he was sorry.” Krieger’s biggest regret is that, while “Oliver Stone’s movie is laughable as a historical artifact, . . . parts of it have seeped into the official record.”

After chronicling the lives of Morrison and his fellow Doors, my colleague Batchelor moves on to appraising the group’s long-term impact. In a smart Afterword called “Jim Morrison in the Twenty-First Century,” he probes the mythic place occupied by Morrison in contemporary culture, quoting Jim’s own self-assessment as a shooting star, a celestial body bound to quickly disappear from view but never be forgotten. This section is followed by some highly personal musings titled “My Doors Memoir,” in which Batchelor explores the impact of Morrison and his fellow Doors on his own youthful life, circa 1986. It is in these pages that he discloses how important the band has been in terms of his own development: “I want to understand Morrison and the Doors because I want to decipher my own life, as well as America writ large across the ages.” Many a Doors fan will surely share this goal.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers