Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 26

April 25, 2023

A Jamaica Farewell to Harry Belafonte

My mother considered herselfthe #1 fan of singer/actor/activist Harry Belafonte, who has just died at theage of 96. All of her adult life she adored Belafonte’s singing, his acting, hispolitical stances, and his dusky good looks. And, of course, she passed on thispassion to her children.

There was a time whenBelafonte regularly brought his electrifying stage show, complete with backupsingers and dancers, to L.A.’s outdoorGreek Theatre. When the dates were announced, my mother would quickly order twosets of tickets. On one night she’d attend with my father. On another, she’dbring my young sister and me to see the great man in person. I mean thisliterally—one year she figured out where the entertainers parked their cars,and stationed the three of us where we’d be sure to meet her hero. It worked. Belafonteemerged, and graciously greeted the dressed-up little girls. (He had some ofhis own at home, so he knew how to talk to kids.) When he complimented me on mypretty dress, I proudly explained that my mother had bought it on sale. It becamea family story that was told many times over. Years later, he was equallyingratiating when I (then a young journalist) met him at a record industryluncheon. Someone snapped a photo, which you can see below. It became aprominent feature of my mother’s kitchen bulletin board.

Belafonte studied actingbefore he became known as a singer of calypso tunes. One of his earliest films,Carmen Jones (1954), was a musical in which he didn’t get to sing anote. This all-Black version of Bizet’s Carmen, adapted from a hit Broadway show, requiredoperatic warbling, and both he and star Dorothy Dandridge were dubbed. Later inthe decade, he starred in screen dramas that always had a racial element attheir core. A Caribbean-set political and romantic drama, Island in the Sun, allowed him to bare his torso on-screenand to romance—with serious consequences—the very blonde Joan Fontaine.

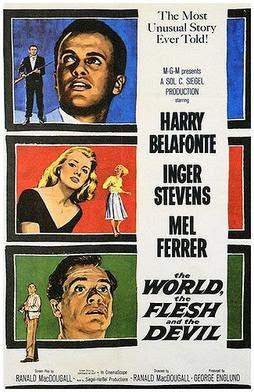

The Belafonte film from the1950s that I remember best is an imaginative apocalyptic story called TheWorld, the Flesh, and the Devil (1959). It’s set in Manhattan, in theaftermath of some sort of nuclear disaster that has rid the city of virtually allits inhabitants. The only survivors in this New York ghost town seem to beBelafonte (a mine inspector who was deep underground at the time of the blast),a pretty young Caucasian woman played by Inger Stevens, and a crusty oldersailor (Mel Ferrer). What we’ve got here, as the survival of the human race seemsin question, is a potential love triangle with strong racial overtones. Thefilm was the first offering of Belafonte’s own production company, dedicated toportraying the African-American experience on-screen.

In later years, as he beganto emphasize social activism over acting, Belafonte took on fewer film roles,though he did appear in movies directed by his close friend, Sidney Poitier.These included 1972’s Buck and the Preacher and the 1974 comedy UptownSaturday Night, in which his crime-boss character, Geechy Dan, is a wickedsend-up of Marlon Brando’s Vito Corleone. As he aged, he continued to take on occasionalroles in films that had personal meaning to him, like Bobby, aboutevents surrounding the assassination of Robert Kennedy. His last film appearance was a powerful one,in Spike Lee’s BlacKKKlansmen (2018) He was over ninety when he playedfor Lee a civil rights activist describing in horrific detail a Klan lynching. May he rest in peace.

April 18, 2023

Four Degrees of Kevin Bacon

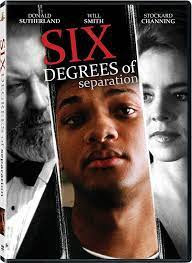

Six Degrees of Separation is a 1993 film, based on a hit Broadway play, inwhich a wealthy, cultured, and liberal-minded couple (Stockard Channing andDonald Sutherland) welcome a personable Black man (the young Will Smith) intotheir posh Manhattan condo. He’s articulate but bedraggled, claiming to be thevictim of a Central Park mugging. After some coy evasions, he admits he’s theson of superstar Sidney Poitier. Of course they urge him to spend the night.

It all smacks of a con—especiallyafter they find him in bed, in the nude, with a second young man—but Smith’sPaul is not your average grifter. The film, which also stars Ian McKellen and astarry cast under the direction of Fred Schepisi, is fundamentally about thehuman need for connection, and about what human beings will do to create bondswith one another. It’s the source of the idea that (to quote Channing’sdialogue at one point) “everybody on this planet is separated by only six otherpeople. Six degrees of separation between us and everyone else on thisplanet.”

The stage version of SixDegrees of Separation, from 1990, was nominated for multiple awards.The film garnered fewer accolades,although Channing (repeating her stage triumph) was in the running for a BestActress Oscar. Part of the problem was that the movie version, despite somecreative directorial choices, still felt like a filmed play. Also, the complex nuances of these charactersand situations probably didn’t come across to moviegoers.

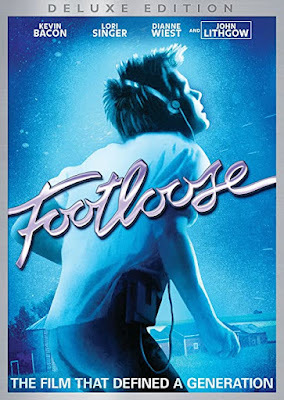

The same can NOT be said of a1984 film called Footloose, in which Kevin Bacon plays a teen fromChicago who teaches some small-town Texans about the joys of dancing. Here’s a musicalthat’s simple, straightforward, and just made for toe-tapping, starting withall those pairs of quick-stepping feet we see under the opening credits,grooving to the catchy beat of the title tune. Catching up with Footloose yearsafter its screen debut, my movie companion and I marveled at Bacon’s skill-set:aside from his personal charm and acting chops, he was apparently a terrific dancerand also a gymnast who could effortlessly twirl on the high bar. That’s when Iread that Bacon—whose movie fame was ensured by this role—had no fewer thanfour doubles on the set. These included a stunt double for fight scenes, adance double, and two gymnastics experts. So the parlor game about “Six Degreesof Kevin Bacon” (a cheeky variant on the Six Degrees of Separation memereflecting how the busy Bacon seemed to have worked with nearly everyone inHollywood) could be adapted to indicate how, in this film, Bacon waseverywhere, doing everything (with a little help from his friends).

Though Footloose iseasy enough to follow (and easy enough to love), it is not totally lacking incomplexity. School dances are banned in this small town because of the effortsof the highly influential local pastor. But, as played by John Lithgow, he isnot merely a zealot or a prude. Instead he’s a man who has turned his sorrowover a family tragedy into a crusadeagainst the elements he believes led to his son’s death. By contrast, his sexyyoung daughter (Lori Singer) has found her own dubious way of dealing withgrief. Naturally, she and Bacon’s character (not to mention his dancing andgymnastic clones) end up connecting, and you can count on an ending in which prettymuch everyone finds happiness.

Which is certainly more thanyou can say for the ambiguous fadeout of Six Degrees of Separation.

April 14, 2023

Regarding Rosalind Russell

Well, it was supposed to befunny. I’m old enough (alas) to remember the Oscar broadcast of 1959. Back inthose days, the show’s musical numbers were not nearly as elaborate as they aretoday. At one point in the evening, three British actresses (one was AngelaLansbury) sang a little ditty about their countrywoman, Deborah Kerr, who wasup for Best Actress for her starring role in Separate Tables. Whilepraising Kerr, they took would-be witty potshots at her rivals for the honor.Regarding Rosalind Russell, they cattily opined that “Your mother couldhave scored with Auntie Mame.”

As a kid I realized full wellthat it’s not nice to compare a film star to somebody’s mother. Still, much asI loved Russell’s madcap performance as the wealthy, uninhibited, fundamentallygood-hearted Mame, I definitely put Russell in the middle-aged category. (She was over fifty at the time.) Yearslater, I was surprised to learn that before World War II she was a glamorousleading lady type, particularly in comedies. After portraying a connivingsociety dame in The Women (1939) she graduated to the leading role ofHildy Johnson, ace reporter and the object of Cary Grant’s affections in thewonderfully screwball His Girl Friday (1940). Her first Oscarnomination came for her portrayal of the savvy but lovelorn elder sister in1942’S My Sister Eileen. Butlater in the decade she was again up for the golden statuette for playing aheroic nun in Sister Kenny (1946) and a tragic heroine in the filmversion of Eugene O’Neill’s Mourning Becomes Electra (1947 – not a lotof laughs in that one!).

In the following decade,Russell was a natural to repeat her Broadway triumph in Auntie Mame. Thefilm version, though overlong, has its own sparkle, as Mame ebullientlyproceeds to adopt an orphan boy, a bashful Southern millionaire, and awoebegone unwed mother into her life. (The last of these plot lines isextraordinarily dated, but Peggy Cass is hilarious – and Oscar-nominated – asthe addlepated Agnes Gooch.)

AS she moved into the 1960s,though, Hollywood didn’t seem quite clear on how to make use of herconsiderable talents. In 1961 she starred in the screen version of a hit stagecomedy, A Majority of One. Broadway audiences had kvelled to theperformance of Gertrude Berg (TV’s Molly Goldberg) as a rather stereotypicalNew York Jewish widow who—against all odds—falls for a Japanese widower (wouldyou believe Sir Cedric Hardwicke?) despite the misgivings of her family. Theidea is that Bertha Jacoby, who lost a son in the Pacific during World War II,has a strong distaste for anything Japanese, until she meets a Japanesegentleman with his own sorrows. Of course it’s meant to be a story of love andreconciliation, and audiences of the day found it heart-warming..

I’m told that Russell herselfwanted Berg to repeat her stage triumph, but bowed to Jack Warner’s insistence that she stepinto the role. She played opposite Alec Guinness, a talented actor known forhis chameleon-like transformations but hardly convincing as an Asian. So a playabout the melding of Jewish and Japanese culture was played by two RomanCatholics with roots in the British Isles, in an era long before our currentpassion for political correctness. Ugh!

In 1962, Russell took onanother hit Broadway role, that of Mama Rose in Gypsy, but it was hardlya triumph, partly due to her limited skill as a singer. She ended her careerplaying funny nuns in two The Trouble with Angels films.

April 11, 2023

Getting to Know “Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison”

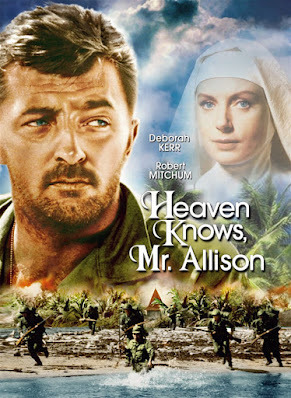

I suppose it’s part of somedivine plan that I watched Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison on Good Friday.This 1957 film certainly reflects its era: it’s a widescreen romanticdrama populated by major stars (RobertMitchum and Deborah Kerr), using World War II as a backdrop for a tale of loveand sacrifice. One of its two central characters is a Roman Catholic nun, and formalreligion is treated with all due respect. Sentimental? Yup—but also anappealing reflection of an era when (at least in theory) men were men, andwomen were decidedly not.

Adapted from a popular novelby an Australian author, Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison, was directed as wellas co-written for the screen by the great John Huston. His filmography was longand varied, but this film most reminds me of 1951’s The African Queen,which contains a similar sense of opposites attracting under dangerouscircumstances. In The African Queen, a prissy missionary (KatharineHepburn) and a rough-and-ready ship’s captain (Humphrey Bogart) bond while on alife-or-death wartime journey down an African river.

Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison is set in a similarly dangerous time and a similarlyexotic place. It takes place on a small Pacific island during the later yearsof World War II. We open with a desperate American Marine, the only survivor ofa Japanese attack, reaching the shore in a rubber raft. Fortunately, the enemyis not present. The island’s sole inhabitant turns out to be a pretty youngBritish nun with her own tale of woe. The only surprise about this meet-cute isthat Allison has no apparent beef against the Church, and from the start treatsthe coiffed and veiled sister with full respect. When it comes to survivaltactics (like catching a giant sea turtle for dinner), he’s endlessly capable,and she’s hardy enough to go along with his every scheme. Once a Japanesesquadron has returned to the island, Mitchum’s character manages a successfulraid on their well-stocked pantry. In addition to canned goods, he comes backwith bottles of sake, but then—thoroughly under the influence—makes themistake of telling Sister Angela that he’s in love with her. Since she has notyet taken her final vows, anything is possible . . . but she flees into thenight in total dismay.

Muchof the film’s acclaim was directed toward Kerr’s performance as Sister Angela,for which she was Oscar-nominated. (The film’s other Oscar nom went toward itsconcise, impactful script.) In this era, Kerr was making something of aspecialty of playing outwardly prim young women who harbor deep emotionsbeneath a ladylike surface. (See The King and I, Tea and Sympathy,Separate Tables, and of course From Here to Eternity.) During along career, she was nominated for six Oscars, always as a leading lady. Shenever won, but thankfully was awarded an honorary Oscar in 1994 as “an artistof impeccable grace and beauty, a dedicated actress whose motion picture careerhas always stood for perfection, discipline and elegance.”

I tend to associate Mitchumwith film noir (like the classic Out of the Past). With hisslightly dissolute look and manner, he could be terrifying, as in 1955’s Nightof the Hunter. In Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison, he’s brash and a bitcrude, but there’s a gentle side to his character as well. The film’s endingcertainly doesn’t leave us with any hints of happily-ever-after. Yet this is a feel-good movie, one that seems tosuggest that all things are possible. And I say Amen to that!

April 7, 2023

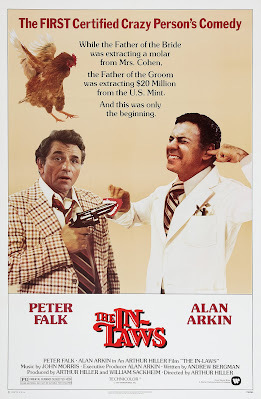

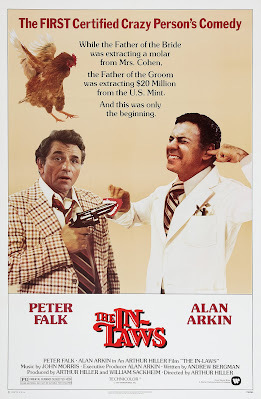

Killing Time with "The In-Laws"

I was startled to learn thatthe great Alan Arkin, a late-in-life Oscar winner for his irascible grandparole in Little Miss Sunshine, once thought he was no good at comedy. Afterall, he‘d burst into the public eye with his wildly funny Oscar-nominated performanceas a Russian submarine officer stranded off the New England coast in 1966’s TheRussians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming. (Arkin lost to PaulScofield’s dead-serious performance as Sir Thomas More in A Man for AllSeasons.) A true character actor, Arkin followed up Russians with avariety of roles: as a deaf-mute in The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, abereaved Puerto Rican dad in Popi, and a thug who terrorizes poor, blindAudrey Hepburn in Wait Until Dark. Eventually it occurred to him that hecould be successfully funny on-screen . . . and that he and Peter Falk would make for an ideal pairing. Hence TheIn-Laws, a 1979 farce that had me in stitches.

A plot summary doesn’t dojustice to the zaniness of this film. The basic premise is that twoin-laws-to-be (Arkin as a meek dentist, Falk as a shifty con-man type) must goon the lam on the brink of their children’s wedding. I’m still a bit confusedby the theft that sets the plot in motion, and by the true nature of the Falkcharacter’s hush-hush affiliation with good guys and bad. But what’s pure goldis the developing relationship between two opposites who suddenly need to worktogether in the direst of circumstances.

A few glimmers of this film’shilarity:

· A masked thug, fresh from a heist, hands over his lootto Falk on a rooftop, while both matter-of-factly exchange pleasantries aboutfamily doings

· Falk whisks Arkin out of his Manhattan office to breakinto a safe, leaving behind a matron who obligingly waits in the dental chairfor his return, her mouth stuffed with cotton, while conscientiously obeyinginstructions not to bite down

· A panicked Arkin, escaping a police raid, zips into adrive-through spray paint establishment, only to find his luxury sedanpermanently adorned with flames.

· Aboard a rickety private plane bound for SouthAmerica, the ageless James Hong (yes, he was the elderly father inEverything Everywhere All at Once), gives the passenger-safety spiel inCantonese and pantomime, panicking Arkin even more

· Arkin and Falk end up on a South American island runby a manic general (the priceless Richard Libertini) who has a most unusualsidekick. (It gives new meaning to the phrase, “Talk to the hand.”)

Farce is not easy, and Isuspect that the examples above, when spelled out in print, might sound dumbrather than amusing. But under the astute direction of veteran Arthur Hiller,Arkin and Falk are so committed to the reality of this insanity that the vieweris rooting for them all the way. WhenStanley Kramer tried to create the funniest movie ever made, It’s a Mad MadMad Mad World, he loaded it so full of shtick, not to mention famous comicactors, that the audience (me) was not amused. Mad Mad World was awhopping 3 ½ hours long, and there was so much going on, in so many differentscrewball styles, that the film felt exhausting. The In-Laws (half aslong, with an able but much smaller cast) is, for me, laugh-out-loud funny, andI know many in Hollywood have felt the same.

Which is why there was a 2003remake, featuring another amusingly odd couple: Michael Douglas and AlbertBrooks. It was a total flop. Don’t be fooled by imitations.

Killing Time with The In-Laws

I was startled to learn thatthe great Alan Arkin, a late-in-life Oscar winner for his irascible grandparole in Little Miss Sunshine, once thought he was no good at comedy. Afterall, he‘d burst into the public eye with his wildly funny Oscar-nominated performanceas a Russian submarine officer stranded off the New England coast in 1966’s TheRussians Are Coming, The Russians Are Coming. (Arkin lost to PaulScofield’s dead-serious performance as Sir Thomas More in A Man for AllSeasons.) A true character actor, Arkin followed up Russians with avariety of roles: as a deaf-mute in The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, abereaved Puerto Rican dad in Popi, and a thug who terrorizes poor, blindAudrey Hepburn in Wait Until Dark. Eventually it occurred to him that hecould be successfully funny on-screen . . . and that he and Peter Falk would make for an ideal pairing. Hence TheIn-Laws, a 1979 farce that had me in stitches.

A plot summary doesn’t dojustice to the zaniness of this film. The basic premise is that twoin-laws-to-be (Arkin as a meek dentist, Falk as a shifty con-man type) must goon the lam on the brink of their children’s wedding. I’m still a bit confusedby the theft that sets the plot in motion, and by the true nature of the Falkcharacter’s hush-hush affiliation with good guys and bad. But what’s pure goldis the developing relationship between two opposites who suddenly need to worktogether in the direst of circumstances.

A few glimmers of this film’shilarity:

· A masked thug, fresh from a heist, hands over his lootto Falk on a rooftop, while both matter-of-factly exchange pleasantries aboutfamily doings

· Falk whisks Arkin out of his Manhattan office to breakinto a safe, leaving behind a matron who obligingly waits in the dental chairfor his return, her mouth stuffed with cotton, while conscientiously obeyinginstructions not to bite down

· A panicked Arkin, escaping a police raid, zips into adrive-through spray paint establishment, only to find his luxury sedanpermanently adorned with flames.

· Aboard a rickety private plane bound for SouthAmerica, the ageless James Hong (yes, he was the elderly father inEverything Everywhere All at Once), gives the passenger-safety spiel inCantonese and pantomime, panicking Arkin even more

· Arkin and Falk end up on a South American island runby a manic general (the priceless Richard Libertini) who has a most unusualsidekick. (It gives new meaning to the phrase, “Talk to the hand.”)

Farce is not easy, and Isuspect that the examples above, when spelled out in print, might sound dumbrather than amusing. But under the astute direction of veteran Arthur Hiller,Arkin and Falk are so committed to the reality of this insanity that the vieweris rooting for them all the way. WhenStanley Kramer tried to create the funniest movie ever made, It’s a Mad MadMad Mad World, he loaded it so full of shtick, not to mention famous comicactors, that the audience (me) was not amused. Mad Mad World was awhopping 3 ½ hours long, and there was so much going on, in so many differentscrewball styles, that the film felt exhausting. The In-Laws (half aslong, with an able but much smaller cast) is, for me, laugh-out-loud funny, andI know many in Hollywood have felt the same.

Which is why there was a 2003remake, featuring another amusingly odd couple: Michael Douglas and AlbertBrooks. It was a total flop. Don’t be fooled by imitations.

April 4, 2023

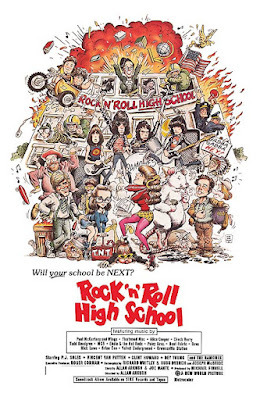

Roger Corman Goes to High School

Each year, as April 5approaches, I find myself musing about my former boss, B-movie maven RogerCorman. Remarkably, this April 5 Roger will turn 97 years old. Hardly therocking chair type, he’s still involved in grinding out low-budget movies, withthe help of wife Julie and a small staff. You won’t find my name on hisWikipedia page (in the wake of my Corman biography he’s had staffers purge mefrom the site). But I’d like to think that my Roger Corman: An UnauthorizedBiography of the Godfather of Indie Filmmaking and its updated version, RogerCorman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers,have helped put into context Roger’s significant contributions to Hollywood. Ialso hope it reveals, despite it all, the affection and admiration I feeltoward the man who inducted me into the film industry.

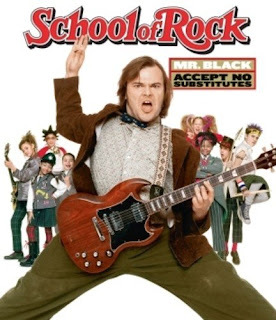

Each year, as April 5approaches, I find myself musing about my former boss, B-movie maven RogerCorman. Remarkably, this April 5 Roger will turn 97 years old. Hardly therocking chair type, he’s still involved in grinding out low-budget movies, withthe help of wife Julie and a small staff. You won’t find my name on hisWikipedia page (in the wake of my Corman biography he’s had staffers purge mefrom the site). But I’d like to think that my Roger Corman: An UnauthorizedBiography of the Godfather of Indie Filmmaking and its updated version, RogerCorman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers,have helped put into context Roger’s significant contributions to Hollywood. Ialso hope it reveals, despite it all, the affection and admiration I feeltoward the man who inducted me into the film industry. This year, my thoughts aboutRoger’s accomplishments are blended with my response to a non-Corman film Ifinally got around to seeing. The Jack Black vehicle, School of Rock,was released in 2003. Black plays a slacker who finagles his way into asubstitute teaching gig at a tony local prep school. With zero ability toinstruct his charges in academic subjects, he manages to form the little nerdsand kiss-ups who populate his classroom into a rock band good enough to scorein a local competition. It’s all charmingly amiable: even the stuffy principal(Joan Cusack), who frets a great deal about threats to the school’s academicreputation, is eventually on board.

This feel-good flick, in whichthe status quo is attacked with no permanent harm done, immediately reminded meof a Corman-produced gem from 1979, Rock ‘n’ Roll High School. This toois a lively film about students resisting the rules of a conventionaleducational institution. The leading characters are teenagers, led by the irrepressiblybouncy Riff Randell (P.J. Soles), who considers herself the #1 fan of the punkgroup known as The Ramones. Once again the students rebel against abehind-the-times faculty, here led by the tyrannical, unbendable principalEvelyn Togar (Mary Woronov) and some arrogant classroom types who will stop atnothing to ban rock ‘n’ roll from the campus. In this world, there are no coolgrown-ups of the Jack Black variety. And the ending is hardly one that showsfriendly reconciliation of the opposing points of view. Instead, we watch thestudents actually blow up their school. It’s a triumph of a very different sortthan that of School of Rock. Though Rock ‘N’ Roll High School hasthe exuberance of a Fifties teen film, its ending promotes a jubilant anarchy.

I’ve had long conversationsabout Rock ‘n’ Roll High School with both director Allan Arkush andoriginal screenwriter Joseph McBride. Joe praises Allan, a passionate pop musicfan, for spearheading this film, back in the days when Roger encouraged youngtalents to take the lead on upcoming projects. He confirms the report that Roger sought to score the film to a differentbeat and call it Disco High,, but that Allan would not be swayed.. He also told me that the building that dramaticallyexploded was Mt. Carmel High School in Watts, a Catholic school that had been condemnedbecause of earthquake safety issues. Corman’s minions rented the building for$1000 from the local priest, not telling him of their plans to blow it up.“This was typical Roger.,” said Joe. At first Allan assumed they’d use a miniature.“And Roger said, ‘Are you kidding? That’s too expensive to build the miniature.You’re going to have to blow up a real school.’”

Happy birthday,Roger. Here’s to many more things that go boom!

March 31, 2023

Consider Yourself a Fan of “Oliver!”

The Sixties were big yearsfor BIG musicals. In an era when television was on the rise, these costlyextravaganzas showed off the pleasures of large-scale spectacle that only amovie screen could accommodate. Winners of the Best Picture Oscar during theSixties included such dazzling and ambitious entertainments as West SideStory (1961), My Fair Lady (1964), and The Sound of Music (1965).And other nominees included Mary Poppins and Funny Girl.

The Sixties were big yearsfor BIG musicals. In an era when television was on the rise, these costlyextravaganzas showed off the pleasures of large-scale spectacle that only amovie screen could accommodate. Winners of the Best Picture Oscar during theSixties included such dazzling and ambitious entertainments as West SideStory (1961), My Fair Lady (1964), and The Sound of Music (1965).And other nominees included Mary Poppins and Funny Girl. But wait! Wasn’t thereanother Broadway musical smash that ended up nabbing the Best Picture Oscarafter the film version was released in 1968? Yes, indeed, but Oliver! wassomething of a horse of a different color. That is to say, Lionel Bart’s stagemusical version of the Charles Dickens novel originated not in New York but inLondon. Musical theatre has always been considered an intensely American artform. But Oliver! showed, long before Andrew Lloyd Webber, that theforces behind British theatre could triumphantly learn from their Americancousins.

In adapting Oliver Twist,set among pickpockets and thieves on the loose in Victorian London, Bart (thetalented son of Jewish immigrants from Galicia) toned down the casualanti-semitism of Dickens’ original story. He cut back on but did not eliminatethe gruesome aspects of Oliver’s milieu, while making sure to keep intact thealmost cloying Dickensian sweetness that shows itself in such highly sentimentalsongs as “Where is Love?” Though Bart’s plot contains the grimmest of murders,as well as a heart-tugging reunion, what audiences remember best is theliveliness of Fagin and his gang of young hoodlums, who certainly seem to enjoytheir work snatching the plump purses of London’s well-heeled citizenry.

I understand the originalstage production made good use of a stylized unit set that didn’t pretend to depicta genuine London street scene. But film, of course, is a far more realistic medium,and the film’s producers aimed for a visually arresting canvas, crammed full ofVictorian detail. When the Artful Dodger encourages shy young Oliver Twist to“Consider Yourself One of Us,” he leads the boy on a romp through crowdedCovent Garden streets where grocers and other vendors ply their wares. (In awarehouse full of hanging sides of beef, the pair even romp straight through alarge carcass that a butcher with a large cleaver has just divided in two.)

The director in charge of allthis on-screen activity is Britain’s Carol Reed, much admired for such grittyurban dramas as The Third Man and Odd Man Out. I don’t pretend tobe an expert, but I believe this was his only musical. Still, he knows a thingor three about teeming cities, and there’s no one better at ratcheting upsuspense. In portraying London’s seedy underbelly, he gives this Oliver! agenuine sense of looming terror that’s rare for musical entertainments. On the flip-side, when Oliver enjoys a briefrespite in the home of a wealthy man, we see (to the strains of “Who WillBuy?”) the street filled with a whole magical parade of bandsmen, milkmaids,and other handsome, healthy folk.

In the where-are-they-now?department, the adorable boy who plays Oliver is now happily retired fromshowbiz and working as an osteopath. Jack Wild, the impish scalawag who earnedan Oscar nom as the Artful Dodger, remained an actor, but succumbed at age 53 todrink and drugs. Oliver Reed, who played the murderous Bill Sikes, similarlycut his life short through reckless behavior. But hurrah for Ron Moody, adeliciously nimble and mischievous Fagin, who survived to the ripe old age of91.

March 28, 2023

The Catch-22 of Translating a Hit Novel to the Screen

At the end of the Sixties the book that everyone was reading was Joseph Heller’s darkly satiric World War II novel, Catch-22. And the movie that everyone was watching was The Graduate, the outrageous romantic comedy directed by Mike Nichols. So there was little surprise, when word spread that Nichols would be directing a screen version of Catch-22, that audiences couldn’t wait to see the results.

Nichols’ film, released in June 1970, unfortunately pleased almost no one. This despite the fact that it was a serious effort to translate a complex, almost hallucinatory, novel to the screen. The Writers Guild of America did nominate Buck Henry’s script as the best screen drama adapted from another medium, but it didn’t win. That same year, M*A*S*H, a much more popular depiction of the truism that “war is hell,” took home a WGA Award for comic adaptation. Perhaps it was the success of M*A*S*H, featuring a lively rendering by Robert Altman of a behind-the-lines Korean War story, that undercut Catch-22’s box-office chances. Or perhaps the brilliant, bitter Catch-22 just couldn’t work without Heller’s sparklingly ironic prose.

Still, it was a worthy attempt. Nichols, who’d shown such visual flair in The Graduate, had fun depicting the almost operatic lift-off of WWII era bomber jets. Having used the songs of Simon and Garfunkel to great effect in The Graduate, he mostly avoided music in the far more serious Catch-22, but at one key point tried an outlandish reference to the opening strains of “Thus Spoke Zarathustra,” familiar to anyone who’d seen 2001: A Space Odyssey. (And, in that era, who hadn’t?)

The large cast is a remarkable gathering of Hollywood talents. Nichols was known for his casting savvy, and we can fully believe Martin Balsam as a gruffly maniacal Col. Cathcart, Richard Benjamin as a smarmy Major Danby, Anthony Perkins as a vulnerable Chaplain Tappman, Bob Newhart as an anxious Major Major, and Orson Welles as a bloated General Dreedle. The leading role, Yosarian, is that of a neurotic cipher, and Alan Arkin is particularly good at conveying his anxiety about war, the U.S. Army, and life in general.

Given the worldwide success of The Graduate, it’s not surprising that Nichols again turned to several performers from that 1967 film. Elizabeth Wilson (Benjamin’s anxious mom in The Graduate) has a tiny but memorable role as the mother of a dying soldier. Norman Fell (the cranky landlord of Ben’s Berkeley rooming house) is seen here as a blunt sergeant. Buck Henry, who had brilliantly adapted Charles Webb’s The Graduate for the screen while also playing a skeptical desk clerk, again performs double duty, donning a creepy little mustache to portray Balsam’s toadying sidekick, Colonel Korn.

Nichols also cast Art Garfunkel, a novice actor and one-half of the musical duo whose songs dominate the score of The Graduate, as the naïve young Nately. (The following year “Arthur” Garfunkel was a central figure in Nichols’ corrosive Carnal Knowledge.) Charles Grodin, who to the end of his life insisted that he’d been cast by Nichols as Benjamin Braddock but had turned the role down, plays the oblivious bombardier on Yosarian’s plane. But what of the screen’s actual Benjamin Braddock? I’ve learned that Dustin Hoffman, whose Hollywood career burst into life with The Graduate, badly wanted to play the shifty Milo in Catch-22. Perhaps Nichols was truly offended that Hoffman took on, immediately following The Graduate, the scruffy role of Ratso Rizzo in Midnight Cowboy. In any case Nichols gave the role of Milo not to Hoffman but to his Midnight Cowboy co-star, Jon Voigt.

March 24, 2023

Benny & Joon & Sam—oh my!

I admit that in real life I’m not a great fan of Johnny Depp. I’ve never been anywhere near him, but his reported behavior toward his fellow human beings (including ex-partners) is not endearing. My hackles were raised when I read in my local paper about his fury at some Sunset Strip developers. As I recall, he threatened a lawsuit against them. After all, they had dared to put up high-rise towers that would mar one corner of the panoramic view of Depp’s children when they played in their Hollywood Hills backyard high above Sunset Blvd. Not that I don’t appreciate unfettered views, but I refuse to worry about the aesthetic pleasures of Depp’s offspring.

There’s no denying, though, that Depp is a major talent, especially in roles of a whimsical nature. His physical dexterity, coupled with a strong sense of unworldliness, helped him break through to fame and fortune in such unique early roles as that of the title character in Edward Scissorhands (1990). Three years later, though he didn’t play a title role in Benny & Joon, his performance was what you carried away from a film whose primary relationship is that between a tense young mechanic (Aidan Quinn) and his mentally disturbed sister (Mary Stuart Masterson). After their parents’ tragic death, Benny has devoted himself to Joon’s well-being, thus inadvertently stifling the emotional development of them both. Joon’s creative rebellions make their lives together disconcerting: early on, after a frustrated housekeeper quits, Joon (wearing a SCUBA mask) is found by the local police directing downtown traffic with a ping pong paddle. Clearly, something has to give.

That’s when Johnny Depp’s Sam comes into the picture. An unwanted relative who’s come to stay with one of Benny’s poker buddies, he ends up tending Benny’s house while also keeping an eye on Joon. His methods are unorthodox: he uses a skateboard to help clean the walls, and a steam-iron to toast cheese sandwiches. None of this is surprising for someone who seems to have modeled himself on Buster Keaton and the silent movie clowns of the past. It’s not long before the two misfits fall in love, and of course complications arise quickly. At one point, Joon is about to be confined to a mental hospital, barring both Benny and Sam from her life. But, since this is fundamentally a romantic comedy, all problems (along with the cheese sandwiches) are ironed out well before the two-hour mark.

I’m sure books can be written about the movies’ handling, over the decades, of mental illness. In popular films of my youth, like 1962’s David and Lisa and 1966’s King of Hearts, those with mental challenges are gentle souls who are perhaps too delicate for the crass world of every day but have a valuable wisdom of their own. They seem fully redeemable by romantic love, which they pursue wholeheartedly and with no fear of future consequences. In fact, the message seems to be that we’re all a bit crazy, and might as well own up to it, for the sake of ourselves and our planet. In the great scheme of things, whether a real-life Joon can build an adult life for herself with Sam’s help is surely debatable. His charm notwithstanding, he’s barely literate, and seems to live in a fantasy realm of his own making. But we’re at the movies, boys and girls,where fantasy outweighs reality every time. This is ultimately a feel-good film that made me feel very good indeed.

A special nod to Rachel Portman’s airy musical score, which helps capture the story’s delicate magic.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers