Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 27

March 21, 2023

The Calla Lilies Bloom Again for "Stage Door" and Jean Rouverol

Hollywood, particularly in the 1930s, loved movies about what it was like to work in live theatre. For movie audiences who lived far from the Great White Way, it was a chance to peek behind the scenes at a glamorous world they wished they knew better. And, of course, movies featuring gaggles of pretty girls were always in fashion. Which is partly why Stage Door was a popular as well as a critical success. The film was based on a play by two Broadway legends, Edna Ferber and George S. Kaufman, but the Oscar-nominated screen adaptation veered so far from the original that the witty Kaufman quipped it should be renamed “Screen Door.”

Stage Door takes place mostly in the showbiz rooming house where scores of aspiring Broadway babies lounge, bicker, and banter, while waiting for their big break. Three of them stand out. Andrea Leeds scored an Oscar nomination for playing the tragic Kay, a talented actress desperate for a leading role she doesn’t land, for reasons that have nothing to do with her ability. Ginger Rogers is Jean, a perky dancer quick with an opinion or a wisecrack. Katharine Hepburn, starring in her first box-office success after four big commercial flops, is Terry, who first seems like a stuck-up socialite but proves her humanity when the chips are down. (Her on-stage entry line, beginning “The calla lilies are in bloom again,” is apparently a knowing reference to an actual Hepburn line in a Broadway play that Dorothy Parker had wittily panned.) The male lead is the always-oily Adolph Menjou, as a producer and seducer who controls the women’s fate.

Stage Door proved to be a star-making vehicle for several other actresses. Lucille Ball scores as one of the rooming house’s dizziest dames. The acerbic Eve Arden and dance phenom Ann Miller have modest roles, but both make a definite impression. As for all the others, it’s hard to sort them out, especially since they’re all young, pretty, and Caucasian. But the end-credits told me that one of them, playing the role of Dizzy, is Jean Rouverol, a then-actress whose importance to the film industry was to lie in a very different direction.

Jean, whom I once met briefly at a writers’ party, moved on from her acting career in 1940, when she married Hugo Butler. He was a prolific screenwriter who in 1941 was nominated for an Oscar for his work on Edison, The Man. His screenplays, ranging from Lassie Come Home to a western called Roughshod, held him in good stead in Hollywood. Jean meanwhile was churning out episodes of TV’s Search for Tomorrow while being a supermom to her kids. (She ended up having six.)

Both Butler and Rouverol were politically leftwing, which meant that in 1951 they faced being subpoenaed by the infamous House UnAmerican Activities Committee. Their solution was to self-exile in Mexico City, where they spent what turned out to be a fairly delightful decade, living next-door to Diego Rivera and enjoying the company of other HUAC refugees, like Dalton Trumbo. Of course they could no longer write under their own names, but Hugo formed a creative partnership with the great Spaniard Luis Buñuel (The Young One) while also writing and directing a well-regarded Little League baseball documentary, Los Pequeños Gigantes.

Refugees from Hollywood, published in 2000, is Rouverol’s memoir of her blacklist years. While not forgetting how many fellow writers truly suffered, she captures the excitement of her family’s HUAC years. saying, “I wouldn't change a moment of it. We were periodically terrified. But we felt like some curious kind of pioneer.”

Dedicated to Susan Henry, who discovered Rouverol's memoir in a book box and gifted it to me.

March 17, 2023

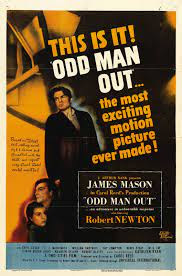

When Irish Eyes Aren’t Smiling: “Odd Man Out”

For St. Patrick’s Day, it seems only right to focus on a film with an Irish pedigree. I could come up with something sweet and lively like John Ford’s The Quiet Man or Disney’s Darby O’Gill and the Little People. Or perhaps a luminous animated adventure like The Secret of Kells. I’ve already written, with great affection, about Martin McDonagh’s Oscar-snubbed but wonderful The Banshees of Inisherin.

So instead I’ll go back in time to praise a classic film by a Britisher, Carol Reed. He’s best known for directing Orson Welles and company in a taut international thriller, The Third Man (1949). And 20 years later he won an Oscar for helming a splashy film adaptation of a Broadway musical, Oliver! But some (including Reed’s biographer) consider his masterpiece to be a 1947 film set in Ireland during the time of The Troubles. It’s called Odd Man Out, Two master directors, Roman Polanski and Sam Peckinpah, cite it as one of their favorite films of all time. It also was the recipient of the inaugural BAFTA award for Best British Film.

Critics have said that Odd Man Out dramatically captures the mood of post-World War II Europe, a time when dread and cynicism reigned supreme. Its backdrop is the ongoing street battle between Protestant and Roman Catholic forces over control of Northern Ireland, though the politics of the matter are not really discussed. Instead this is fundamentally a human rather than a political story, set in a Belfast that is never named. The focus is on a small cell of rebels who have been called on to commit a robbery in support of their cause. Their leader, Johnny, has been in hiding for six months following his escape from prison. He’s determined to do his part, though his weakened physical condition makes others beg him to stay behind. Of course the inevitable happens: he lacks the agility to make a quick escape, and suddenly he’s a fugitive.

Johnny’s local fame is such that he’s immediately recognized by much of the citizenry, while his comrades too are endangered by his mishap. We see a cross-section of city life: a priest who supports him, a well-heeled woman who betrays him, an eccentric who haplessly tries to help, lovers who stumble on him as he’s hiding—badly wounded—in a storage shed. His goal, in his increasingly disoriented state, is to get to the harbor. But the arrival of the young woman who loves him changes the equation, leading to an ending that’s intensely dramatic but also foreordained.

.Most of the actors in Odd Man Out, beautifully playing slice-of-life roles, were affiliated with Dublin’s famed Abbey Theatre. But the leading man was an Englishman, James Mason, long before his Hollywood successes in such films as A Star is Born, North by Northwest and Lolita. Richard Burton noted in his diary that the part was originally offered to another Brit, Stewart Granger. But Granger, thumbing through the script, concluded that the role wasn’t big enough to interest him. What he overlooked was the fact that the part of Johnny—though short on dialogue—is intensely dramatic. He may not have much to say, but his plight, as a wounded man watching his death approach, is riveting. Wrote Burton, “It's probably the best thing that Mason has ever done and certainly the best film he's ever been in while poor Granger has never been in a good classic film at all.” According to Burton, “Granger tells the story ruefully against himself.”

May the road rise up to meet you!

March 13, 2023

An Everything Bagel for “Everything Everywhere All at Once”

Well, it’s official: EverythingEverywhere has now won everything everywhere, including the Oscar for Best Picture of 2022. I wish I had liked it better. I was so willing to challenge my initial impression—formed while I (somewhat sleepily) watched it from my living room couch—that last week I sought it out in an actual theatre. This time I stayed wide awake, and discovered lots of new instances of the film’s whimsical cleverness. But at a certain point I started to feel it was repeating itself. Am I the only moviegoer convinced it would have been a better movie if it were 30 minutes shorter? (A friend walked out early, saying the film made her feel assaulted.) I did love all the leading actors, and felt they earned their accolades, but enough is enough, right? Hotdog fingers can only amuse us for so long.

I do admit I got a kick of Everything Everywhere’s use of a bagel motif to suggest the mysterious unity of the cosmos. A century ago, a bagel was an ethnic snack known only to Jewish immigrant-types in places like New York City. When I read The Rise of David Levinsky, a 1917 novel about a Jewish man starting life over in the New World, I came across a passage in which—suddenly homesick—David was comforted by finding on the streets of the Lower East Side someone hawking the “ring-shaped rolls” he’d known back in Russia. I was momentarily stymied: what in the world was a ring-shaped roll? Suddenly it came to me. He’d found the bagel man . . . but readers of English-language novels in 1917 would not have known the word.

Now, of course, bagels are a worldwide phenomenon, although they take on the coloration of different cultures. (I saw edamame and banana-flavored bagels being sold in Kyoto, Japan.) Everything Everywhere, though, is probably the first movie in which they’ve played a major symbolic role. Yet bagels, I’ve discovered, have also entered the English language (in tennis scoring, for instance), as a slang indication of nothing, or zero. This being so, one of my big regrets regarding this year’s Oscar event was that some mighty fine movies got bageled. I’m not talking simply of small art-house flicks like Living, which was nominated both for its adapted screenplay and for Bill Nighy’s rich performance. Martin McDonagh’s complex and fascinating The Banshees of Inisherin was nominated for 9 Oscars, all of them in major categories, and couldn’t manage a single win. Likewise the admirable Cate Blanchett starrer, Tàr. Steven Spielberg’s deeply-felt The Fabelmans got 7 noms, including one for its John Williams score, but it too came up empty.

Some bageling went on in the always poignant obituary segment of the evening too. This year’s tributes seemed to include a larger than usual number of movie craftspeople, along with the vaunted celebrities. That’s entirely fitting and proper., and I was pleased to see recognition of Mike Hill, one of Ron Howard’s longtime film editors, along with Angela Lansbury and producer Walter Mirisch (In the Heat of the Night). Actor Robert Blake, whose checkered career included the role of a murderer in 1967’s In Cold Blood as well as an actual murder rap in 2001, may have died too recently to be included, though host Jimmy Kimmel mentioned him in a tantalizing quip. But it would have been nice to recognize the low-budget side of the industry, where Jamie Lee Curtis got her start, through a reference to Bert I. Gordon, beloved as Mister B.I.G. to millions of B (for Bagel?) movie fans.

March 10, 2023

Honoring Movies Meant for Grownups

As award season culminates with the presenting of the Oscars on March 12, I’m reminded of another awards event. The AARP Movies for Grownups Awards were instituted by the editors of AARP’s magazine. Their goal: to encourage Hollywood to produce more films by and about people over age 50. All winners and nominees must have hit the half-century mark, so johnny-and-jane-come-latelys like youthful Oscar nominees Paul Mescal (Aftersun) and Ana de Armas (Blonde) are out of luck .

There was a time when the American Association of Retired Persons put out a magazine called Modern Maturity. As a bookworm who’d read just about anything, I checked it out at my grandparents’ apartment, finding it incredibly dry and dull. But 2002 was a big year for the group: Modern Maturity metamorphosed into a chatty lifestyle bi-monthly called AARP The Magazine, which has 37 million readers, making it one of the largest-circulation publications in the U.S. Since senior citizens often have discretionary income, their clout at the box office can be considerable. If, that is, they’re willing to leave their living rooms and head for the cineplex.

So—what projects and performers have been deemed worthy of AARP recognition? The top award was selected from a familiar group of films that include Elvis, Everything Everywhere All At Once, The Fabelmans, Tàr, The Woman King, and Women Talking. Most of these are Best Picture Oscar nominees, but their appeal to the AARP editors seems clear: they reflect long-ago eras and (by extension) the distance between the past and the present. I wasn’t surprised to see Baz Luhrmann honored for directing Elvis, a film about the king of entertainment at a time when some of us were young. And it seemed only fitting that the magazine’s top award should go to Top Gun: Maverick, an action flick whose message seems to be that you’re never too old to save the world. It was lovely to see 87-year-old Judd Hirsch beat out Ke Huy Quan and others for his powerful though brief supporting performance in The Fabelmans, and also 71-year-old stage and screen veteran Judith Ivey recognized for her ensemble work in Women Talking. Among the Best Actor and Best Actress candidates, I delighted in the inclusion of Tom Hanks (A Man Called Otto), and Lesley Manville (Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris). These films are squarely about what it means to get older. But the winners, inevitably, were Oscar favorites Brendan Fraser (The Whale) and Michelle Yeoh (Everything Everywhere All At Once).

There are several unusual categories that don’t make it on the Oscar list. The sadly overlooked movie Till (about civil rights martyr Emmett Till and his grieving mother) here nabs an award for Best Intergenerational Movie. Elvis has been given the Time-Capsule Award, for returning some of us to the days of our youth. I adore the idea of a Best Grownup Love Story. Notably, the nominees are mostly unfamiliar to me, and I’m still waiting for a chance to see the AARP winner, Good Luck to You, Leo Grande. How nice that AARP recognizes, as Hollywood mostly does not, that oldsters too can fall in love. And who can argue about a career achievement award for the ageless Jamie Lee Curtis?

There’s one category, discontinued in 2017, that I’d like to see reinstated: AARP Movies for Grownups Award for Best Movie for Grownups Who Refuse to Grow Up. The winners were movies intended for the younger set that seniors still enjoyed, like Spirited Away and School of Rock. How I’d love to have seen the brilliantSpider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse so honored.

March 7, 2023

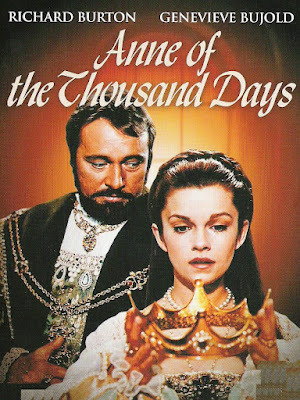

Days Gone By: “Anne of the Thousand Days” and the Oscar Films of 1969

It was Hilary Mantel’s wonderful Wolf Hall trilogy about Thomas Cromwell, the all-powerful “fixer” in the service of England’s Henry VIII, that led me to watch a starry 1969 film, Anne of the Thousand Days. In this classic costume drama, Henry is played by Richard Burton. His imperious performance here is far more interesting than the long-suffering roles (like that in the film Becket) he’d played earlier in the decade. Stalwart character actors, including Anthony Quayle as Cardinal Wolsey, are also shown to good effect.

I was looking forward to seeing Canadian actress Genevieve Bujold as Henry’s second wife, Anne Boleyn. Bujold had won my heart for her spirited yet deeply innocent portrayal of Joan of Arc, in a TV adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan. (This was the era when Hallmark Hall of Fame could be relied upon for glossy versions of the classics.) I had expected Anne of the Thousand Days to view the doomed queen with sympathy. But to my surprise, Bujold as Anne doesn’t make a lot of sense. She boldly stands against King Henry when he forces her away from her first love, treating him with angry disdain. When Henry humbly pleads for her affection, she scorns him. Then, presto!, she declares her affection. As Henry’s newly-crowned queen, she’s cranky as all get out. The fact that she’s blamed for not producing a male heir doesn’t help, of course. But when Henry accuses her of infidelity and witchcraft, I wasn’t all that sorry to see her led to the chopping block.

In retrospect, what’s interesting about Anne of the Thousand Days is the era in which it was released. Historical dramas about the doings of royalty had, since the beginning, been a Hollywood staple. Audiences had always seemed to appreciate dramas set long ago and far away. I gather this was still true in 1969: Anne did well at the box office, and was nominated for 10 Academy Awards. There were three acting nominations (Burton, Bujold, and Quayle), and one for the screen adaption of Maxwell Anderson’s Broadway play. The craft categories also got nods, and the film was up for Best Picture. After all that, it must have been a disappointment to everyone concerned that Anne won only a single statuette, for its sumptuous costumes.

The 1969 films and performances honored by the Academy in 1970 are a fascinatingly mismatched lot. The Best Actor Oscar was a nod to old Hollywood: Burton was bested by John Wayne in True Grit. Best Actress was Maggie Smith, near the start of a long career with a bravura performance in The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. In support, Anthony Quayle lost to that complex figure, Gig Young, a standout as a sinister emcee in one of the darkest and most brilliant films I can remember, They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? Cutie-pie newcomer Goldie Hawn was honored in support for a blithe Broadway comedy, Cactus Flower. And the Best Picture winner was the gritty Midnight Cowboy, first and only X-rated film to take home the top award. Aside from some nods to tradition, 1970 was a mostly a year for honoring material that strove to connect with the youth audience and make sense of the modern world. (Butch Cassidy, Easy Rider, Alice’s Restaurant, and The Wild Bunch all received some recognition.) How did Anne of the Thousand Days fit into this trend? Frankly, not at all. The most honored films of 1969 recognized the modern age. Voters understood that Anne was too distant in its concerns to have much real impact in a complicated era.

March 3, 2023

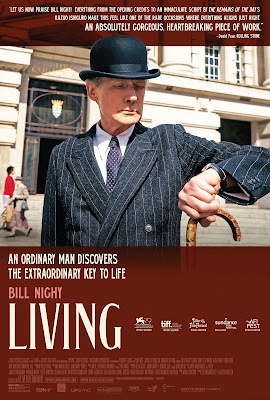

Staying Alive: “Living” as an English Take on a Kurosawa Masterpiece

I first encountered Bill Nighy back in 2003, playing the ageing rocker in that Christmas-time classic, Love Actually. There—sardonically flogging his new and clunky Yuletide version of a rock classic--- he was profane and outrageous . . . and absolutely hilarious. Since I had never consciously seen Nighy on screen before, it was easy to assume that the role reflected his basic personality type. Obviously, he was an iconoclast. Nothing changed when I learned he had played the comically grotesque Davy Jones in two Pirates of the Caribbean films.

My opinion started to shift in 2011 when Nighy was part of the ensemble in another gathering of Britain’s finest thespians, The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel. Now he had transformed into the meek husband of a shrill harridan (Penelope Wilton). By the end of the film, their marriage has blown skyhigh, and he’s making a romantic connection with lovable widow Judi Dench. As I recall, our last glimpse of the duo is aboard a motorbike, zipping joyously through the streets of Jaipur.

But none of the above had prepared me for Nighy’s hauntingly emotional star turn in a small 2022 film that has earned him a Best Actor Oscar nomination. Living is based on a 1952 film by the great Akira Kurosawa. Although Kurosawa’s reputation mostly rests on costume dramas like Yojimbo and Seven Samurai, Ikiru(starring Takashi Shimura) is set in what was then present-day Tokyo. The Japanese title translates as “to live,” and is inspired by Kurosawa’s reflections on his own future mortality. It’s the story of a hard-working bureaucrat who—discovering that he’s dying of cancer—struggles to cope with the time he has left. A deeply self-contained man, he experiments with hedonism, but finally finds meaning in using his work to contribute in a small way to the common good. This is a positive message, but it’s balanced by an ending that’s quietly sardonic.

I’m fascinated by the shift of the story from Tokyo to London, as accomplished by screenwriter Kazuo Ishiguro, the perfect man for the job. A novelist, screenwriter, and 2017 Nobel laureate, Ishiguro was born in Japan but moved with his parents to England at the age of six. His best-known literary works, like Remains of the Day and Never Let Me Go, are set in the United Kingdom, and feature fully English characters. Still, his family connection to the land of his birth gives him a helpful dual perspective on the British Isles. Ishiguro brings an acute cultural sensitivity to Living, a story that plays on the similarities and differences of British and Japanese culture.

Those who’ve studied Japan know that the Japanese have long felt a cultural identification with England. Both Japan and England are island nations with an ancient tendency toward class distinctions, social decorum, and stiff-upper-lip response to the challenges of life. Notably, this new English version of Kurosawa’s film is also set circa 1952, rather than in our present day. My guess is that today’s London—much more multicultural and rambunctious than in the post-World War II period—would not suit this story. The London of Living is a place of bowler hats and strict codes of behavior. But it’s also a place of unwieldy bureaucracy and a general indifference to the unfortunates who look to government officials for help with their daily lives. (In this it certainly seems modern as well as dated.)

Nighy’s tender, deeply-felt performance will long stay with me, as will some of the film’s smaller roles. Now I’d like to go back and watch Kurosawa’s Ikiru again.

February 28, 2023

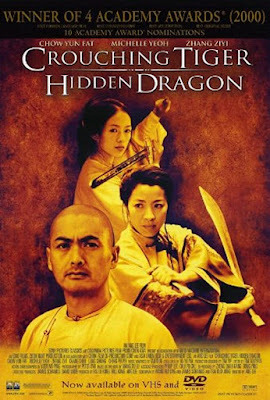

The Rise of a Tiger Mom: Michelle Yeoh in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

While the cast and crew of Everything Everywhere All At Once revel in a essential takeover of Awards Season, can Oscar glory be far behind? My own enthusiasm for this inventive but strenuously confusing lark of a film is not wholehearted, but I’m happy for the attention being paid to the whole glorious tradition of Chinese action movies. I do love seeing Asian men (and women!) fly through the air while performing feats of derring-do. And I’ve long had a deep affection for the lovely and talented Michelle Yeoh, the Malaysia-born actress who grounds every role she plays—however outrageous it might be—with dignity and down-to-earth humanity.

Many western filmgoers first met Yeoh as the steely matriarch in 2018’s Crazy Rich Asians, a satirical romp that some have found borderline offensive in its focus on wealth and power among the Chinese families of Southeast Asia. Yeoh is wonderful in that film, of course (especially in the pivotal mahjong scene), but it only gives us a small glimpse of her versatility and her physical gifts. That’s why I was thrilled by the re-release of Yeoh’s triumphant 2000 film, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. This lavish production from Taiwan, an early career triumph for director Ang Lee, was the rare foreign language entry to be nominated for a Best Picture Oscar. This was the year when the top prize went to Gladiator, but Crouching Tiger won for its cinematography, art direction, and Tan Dun’s musical score while also collecting the expected award for best foreign language feature. (Clearly, the Academy was in the mood to honor costume dramas of epic proportions).

Doubtless because of Yeoh’s ubiquity these days (I’m sure the videotape of her outrageous ad lib at Sunday’s SAG Awards has gone viral), Crouching Tiger is now back in actual theatres. How wonderful to see this film as it ought to be seen. Especially in the pandemic era, I well know the charm of curling up on your living room couch to watch a film. Still, large-scale movies are made for—and deserve—larger-than-life screens. As I lounged in my comfortable thaatre seat, everything impressed me: the music, the pacing, all the central performances, the immense scope of the action. This was a long-ago and far-away world I didn’t know, but one I was thrilled to explore.

The chief critic at the Los Angeles Times, has reported that the film, for all its success in the west, was NOT an enormous hit in Asia. Perhaps it deviated too much from the formulas that Chinese movie-goers expect in their entertainments. In any case, it tells a story that is both highly formal and highly emotional, involving 19thcentury warriors trained in the mysterious arts of the Wudang sect. They fight off their enemies, bounding high into the air, in the service of some noble cause—in this case the preservation of the 400-year-old sword named Green Destiny. While fighting hard, they also love hard, but are also bound by strong internal rules, like the one that keeps Yeoh’s character, Yu Shu Lien, apart from the noble Li Mu Bai (Hong Kong action star Chow Yun-Fat). What complicates matters is the exquisite young Jen Yu (Zhang Ziyi), who sometimes works in close collaboration with Yu Shu Lien and sometimes fights tooth-and-nail against her. A true wild card, Jen may be the crouching tiger of the tale, or more likely its hidden dragon. Her enigmatic behavior in both war and love keeps the plot moving. And I for one adored the fact that women can be fighters as well as lovers.

February 24, 2023

From Uncle Tom to Sweet Sweetback: The Academy Museum’s New Exhibit

As Black History Month winds down, I want to consider the Academy Museum’s new major exhibit. Called “Regeneration: Black Cinema 1898-1971,” it’s slated to run through July 16, and it’s well worth seeing for its insights into how African-American actors and interracial subject matter came to be a part of mainstream Hollywood motion pictures.

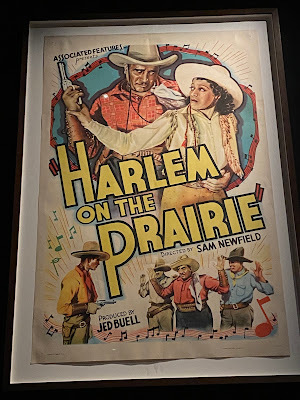

In cinema’s early days, Black characters were exclusively played by white actors in dark makeup. This held true when the characters were evil (the rapists and rapscallions who go after white women in Birth of the Nation are the obvious example). But it also applied when they were sympathetic, as in many early filmed versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The exhibit’s second room, which includes the provocative “Balcony Seating Only” installation, reminds us that Black audiences who chafed at the indignities of segregation once flocked to so-called “race movies.” Films like 1937’s “Harlem on the Prairie,” starring Herb Jeffries, mimicked popular Hollywood genres (for instance, the western and the detective story) but featured all-Black casts.

It was the advent of the musical that allowed African-American performers to become increasingly popular with white audiences. The exhibit pays tribute to such crossover 1940s talents as the Nicholas Brothers (seen in their fabulous staircase number from Stormy Weather) and the sultry Lena Horne, a great favorite of my parents. Of course some terrific film clips from musicals like Porgy and Bess (1959) and Carmen Jones (1954) are on view. While watching the latter I was thrilled to spot my first teacher, future Kennedy Center honoree Carmen de Lavallade, among the background dancers.

Some Black musical talents were featured in white films too, but generally in roles that could be snipped out for the Southern market. In this section of the exhibit I learned for the first time about “soundies,” two-minute musical presentations viewable by the Word War II-era public through coin-operated machines located in nightclubs and other gathering spots. The soundie has been called an obvious precursor to today’s music video: at the museum I watched Fats Waller outrageously mugging to “This Joint is Jumpin’” and Cab Calloway extolling the charms of “Minnie the Moocher.”

There’s a big jump from the musicals of the 1940s and 1950s to the era when Sidney Poitier played out on screen the tough issues facing African-Americans within the unfolding history of this nation. The exhibit naturally showcases Poitier’s landmark Oscar win for Lilies of the Field, as well as his appearance in such controversial hits as Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner and In the Heat of the Night (both 1967). Appropriately, visitors can watch the clip of Poitier, his eyes flashing in anger, returning the slap of a bigoted Southern land-baron in the latter film. But this focus on Black stars does not preclude attention to rising Black directors like the gutsy Melvin Van Peebles, whose bold and angry Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971) pointed the way toward the so-called blaxploitation era.

I realize that exhibits such as this one are constrained by what they can realistically cover. Time and space are not, needless to say, limitless. But I’m curious to know why 1971 was chosen as an ending date for this exhibit. The evolution of the heroic and strait-laced Poitier persona into Shaft and Superfly is surely worth exploring. And I’d love to know about the changing dynamics of audiences who are increasingly ready to root for a Black character more human and more flawed than those Poitier once played. Which, I guess, means a second part to “Regeneration” is much needed. When it opens, I’ll be there.

February 21, 2023

Spirited Away to Howl's Moving Castle

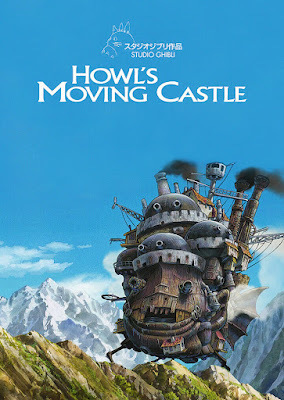

When it opened in September 2021, the new Academy Museum devoted its top exhibition floor to a major retrospective of the work of Hayao Miyazaki. The 82-year-old Japanese animator, who has been internationally acclaimed for his prolific work as a writer, director, and manga artist, is best known for films that explore the supernatural. Miyazaki’s work (like My Neighbor Totoro and Spirited Away)often features children in whimsical settings, but his imaginary worlds are hardly benign places. This is tougher stuff than the Disney universe., but real beauty is also present.

While I was browsing the huge and very colorful Miyazaki exhibit, the section that caught my eye was devoted to a film I’d barely heard of. The centerpiece of Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) is an enormous, ramshackle structure with anthropomorphic elements like legs that give it movement and an entrance like a gaping mouth. When I studied the footage of the castle, set against a gorgeous rural vista, I was completely captivated. Clearly Miyazaki was captivated too—by British author Diana Wynne Jones’s 1986 fantasy novel of the same name. As in Miyazaki’s screen adaptation, it focuses on a sensible, hard-working young woman named Sophie, who is first seen trimming bonnets in her family’s modest hat shop. Sophie lives in a market town that is vaguely Dickensian: it’s quaintly Victorian in style but with a nervous sense of a coming Industrial Age. Magic is always lurking too: in nearby communities live kings, queens, and wizards, including the attractive but dangerous Howl. When Sophie runs afoul of the evil Witch of the Waste, she finds herself transformed into a decrepit but feisty old lady who knows better than to stick around. That’s how she finds herself, after an encounter with a surprisingly devoted scarecrow, coming to live in Howl’s moving castle, along with a fire demon named Caliper and assorted others.

It's a complicated novel, and Miyazaki cuts some of Sophie’s intricate family story as well as hints of Howl’s long ago and far away upbringing. Surprisingly, he turns some of Wynne Jones’ scariest characters (like that witch) into comic relief and re-thinks the whole power structure of the royal kingdom that looms so large in the book. One thing he leaves intact is Howl’s castle’s wonderfully magical doorway: from the inside you spin a knob that determines if you’ll exit into Sophie’s market town, or the bustling seaside city of Porthaven, or the royal capital of Kingsbury, or a mysterious place linked to Howl’s own past. Miyazaki clearly revels in Howl’s rather vainglorious good looks, and particularly into Howl’s ability to transform himself into giant swooping birds and other critters. He also allows us occasional glimpses of the youthful Sophie who still exists, despite her transformation into an elderly body.

Most striking, Miyazaki adds to Wynne Jones’ story a sense of impending military doom. The stiffly uniformed legions who strut through the towns are a marked contrast to all the homey townfolk, and we see the sky being polluted by sinister aircraft. Ecological disaster is much on Miyazaki’s mind in several of his films, and war seems to be another way in which men and women push themselves to the brink of destruction. Thank goodness, though, for a happy ending.

The English language version of Howl’s Moving Castle, lovingly overseen by Pixar, features the voices of such legendary talents as Christian Bale, Lauren Bacall (as the Witch of the Waste), and an elderly Jean Simmons as the old-lady version of Sophie. Though their voices are classy, you’ll remember Billy Crystal as a wisecracking fire demon.

February 17, 2023

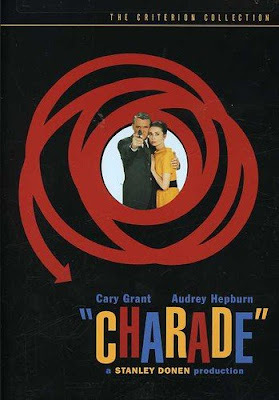

Captivated by “Charade”

Valentine’s Day is a grand excuse to catch up on romantic films. The 2022 additions to the National Film Registry include some great ones. When the list was announced last December, I was otherwise engaged. But Valentine’s Day 2023 reminded me that, two months back, several classics of the genre were deemed worthy of Library of Congress preservation. For the animation crowd, there’s Disney’s charming and family-friendly The Little Mermaid. For rom-com lovers (and lovers in general), there’s the wise and witty When Harry Met Sally. Not only is this one of the most quotable movies of all times (“I’ll have what she’s having”) but it makes a trip to a certain crowded Lower East Side deli much more exciting. Manhattan, of course, is always a popular backdrop for screen romance. But me, I’ll take Paris . . . and another entry on the Library of Congress list. Yes, I mean Charade.

I never saw Charade when it was first released in 1963. Frankly, I tended to confuse it with another delightfully wacky romantic comedy from later in that decade: How To Steal a Million. There was a certain amount of overlap between the two: Audrey Hepburn in Givenchy and Paris in the spring, both on grand display. Charade of course had a musical theme that was on everyone’s lips: Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer’s lilting (and Oscar-nominated) song remains a classic, and I can’t imagine how it was beaten out for the statuette by “Call Me Irresponsible,” from something called Papa’s Delicate Condition.

What Charade also has is a real sense of danger. Even as the story begins, with Hepburn’s character lunching al fresco, backed by snowclad mountains, the barrel of a pistol pokes into the frame. It’s a joke involving a naughty kid with a squirt gun, but the possibility that anything can happen does linger. Hepburn’s Regina may be a kook given to rattling off droll non-sequiturs, but there’s a real sense of shock when she returns home from her ski vacation to a palatial flat that’s completely empty, along with the news that her husband has been tossed from a train while on a baffling errand. And then there are those three Ugly Americans (played by Hollywood stalwarts George Kennedy, Ned Glass, and James Coburn) who keep following her around, demanding a huge sum of money . . . or else!

What’s a girl to do? If she’s Audrey Hepburn in Charade, she turns to the older and wiser Cary Grant, an innocent bystander—or is he? Charade does a remarkable job of encouraging our emotions (like Hepburn’s) to turn on a dime, while blood is shed and promises are proven to be lies. Cheers to the screenwriters, and to director Stanley Donen, who keep us guessing as to where all the twists and turns will lead.

Looking back, the early Sixties was a wonderful era for satisfying film entertainment. Stars like Hepburn and Grant were larger than life: they were as beautiful as the bad guys were ugly. Paces were swift, and outcomes (after a lot of canny misdirection) were what we’d want them to be. After the lights came up, there was nothing to be puzzled about, and no social ill that we’d been charged with fixing. Lively, jazzy music made sure we were effortlessly swept along by a cleverly designed story. In Charade, even the opening credits contribute: after some somber shots of a railroad train and then a man tumbling down an embankment, the screen erupts into a kaleidoscopic frenzy of neon-colored lines and squiggles. Ah, Paris! Ah, Hollywood!

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers