Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 24

June 30, 2023

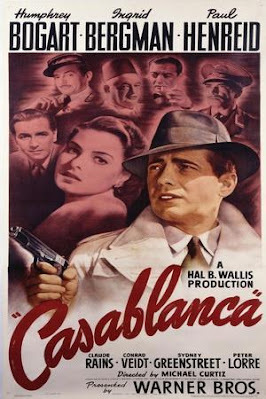

Here’s Looking at You, Casablanca

Recently I was on a transatlantic flight: destinationMorocco. The plane landed at Mohammed V Airport in Casablanca, the country’slargest and most international city. One of many choices on my plane’s seatbacktelevision screen was that golden oldie from 1942, Casablanca. It’sstill revered, more than 80 years later, as one of the great screen romances ofall time. The movie’s ability to combine a poignant love story with a World WarII thriller is part of why it’s lasted so long. Among its many honors, it wasin the first class of films accepted (in 1989) into the National Film Registry dueto its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance.

The release history of Casablancais a fascinating one. The film’s setting in a North African city that wasthen part of a French protectorate but also served as a gateway to far cornersof the globe ensured there’d be plenty of on-screen friction between a multitude of nationalities. Casablanca wasreleased at the height of World War II, so of course the worst of the bad guyswho frequent Rick’s Café are Nazi officers. They’re linked with functionariesof the French Vichy government who perform their duties under the heavy Germanthumb. That’s why in March 1943 the film was officially banned in Ireland,which sought to retain its wartime neutrality. Two years later, Casablanca wasfinally released in Ireland, after trims were made to romantic dialoguefocusing on Rick and Ilsa’s Paris love affair.

Of course German audienceswould not see Casablanca until long after the war was over. A shortenedand heavily edited version was released by Warner Bros. in West Germany in1952. Remarkably, this de-Nazified Casablancachanged Ilsa’s husband, Victor Lazlo, from a heroic Czech Resistancefighter who has escaped from a Nazi concentration camp to a Norwegian atomic physicist who hasbroken out of jail. It was not until 1976 that German audiences could watch thefilm in its original version.

Lovers of Casablanca alwayspoint to the dramatic intensity of the film’s supporting players, especially inthe famous “duel of the anthems” sequence. Nazi soldiers kicking back at Rick’s Café enthusiastically begin to sing“Die Wacht am Rhein,” but their voices are drowned out by the rest of thecrowd’s heartfelt rendition of the Free French anthem, “La Marseillaise.” The closeups in this section are dramatic,partly because so many of the players—notably Madeleine LeBeau, Marcel Dalio,Peter Lorre, and Conrad Veidt—were themselves exiles and refugees. (Ironically,Jewish actors who had fled Europe during Hitler’s reign often found theircareers depended upon playing Nazi roles in Hollywood.)

The screenplay for Casablanca,based on an unproduced play, was the work of many hands, notably those ofbrothers Julius and Philip Epstein. The story goes that the Epsteins and otherswere busy writing even while the film was being shot. That’s why Ingrid Bergman,as Ilsa, honestly wasn’t clear on whether she’d be getting on a plane with herhusband (Paul Henreid) or staying behind with onetime love Humphrey Bogart.She’s said to have faulted her own performance because she wasn’t sure as anactress which option her character would choose. But generations of moviegoersagree that her uncertainty was exactly right for this film.

Casablanca was rushed onto movie screens to tie in with thereal-life North African offensive that put the locale on the international map.How well does the film reflect the actual city? Not at all, because it wasfilmed on a Hollywood backlot. There’s a Rick’s Café in today’s Casablanca, butit’s strictly a tourist trap.

Much has been writtenabout the making of this film. I’ve used other sources, but want to cite hereNoah Isenberg’s 2017 publication, We'll AlwaysHave Casablanca: The Life, Legend, and Afterlife of Hollywood's Most BelovedMovie

June 27, 2023

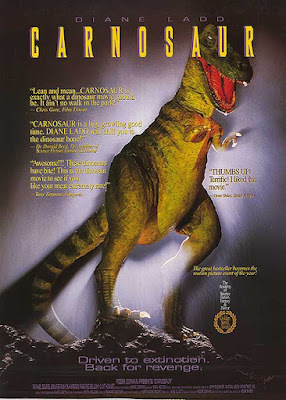

"Jurassic Park” and “Carnosaur”: When Dinosaurs Galumph Down Memory Lane

Thirty years ago this month, thenation held its collective breath, wondering how Steven Spielberg would bringto the big screen Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park, a bestselling novel about dinosaurs runningamok in the modern world. And what was I doing around that time? Along with othermembers of Roger Corman’s creative staff, I was patting myself on the back,overjoyed that we at Concorde-New Horizons had managed to scoop Spielberg. Notin terms of lavish production values, of course. Hardly endowed withSpielberg’s access to CGI technology. we had managed to come up with only asingle tyrannosaurus. Roger decreed that it be eighteen feet tall, thusout-Spielberging Spielberg. But the ceiling of our rather make-shift Venicestudio was only sixteen feet high, so the height requirement had to go.

It all began while theCrichton novel (first published in 1990) was being transformed into a motionpicture. Always quick to sense the national pulse, Roger set aside a projectdramatizing the bloody L.A. civil uprising of 1992 in order to bring his owndinosaur movie to the screen. Our mandate: to get our film into theatres beforeJurassic Park opened, thus luring in viewers who couldn’t wait a momentlonger to watch rampaging dinosaurs First, of course, came the script. Rogerpurchased a novel by the Australian sci-fi novelist, John Brosnan. A man whoknew how to make a buck, Brosnan had published back in 1984 a novel called Carnosaur,under the nom de plume Harry Adam Knight. I read it in the line of duty, looking for plotideas, but didn’t find them in the book’s turgid pages. We at Concorde notedthat the initials of Harry Adam Knight could certainly stand for “hack.” Thisnovel was hack-work, pure and simple. Without question, we needed to start fromscratch. All we kept from Carnosaur was its title . . . and maybe that chicken farm set-up.

Roger hired a bright butspelling-challenged USC film school grad, Adam Simon, to write and direct ourdinosaur movie. Perhaps influenced by the opening of Brosnan’s novel on achicken farm, Adam concocted a story about a mad scientist, working for themysterious Eunice Corporation, who manipulates chicken embryos into futuredinosaurs, the better to undermine the human race. The plotline allowed forlots of gory footage, and we hired a big-name actor for the key role of Dr.Jane Tiptree. While in Jurassic Park young Laura Dern was running fromdinosaurs, we had her mother, Diane Ladd, playing the scientist who stirs upall the chaos. I don’t know if Ladd was the first-ever female madscientist in the movie world, but she was outstandingly creepy. It was largely thanksto her vivid performance that TV reviewer Gene Siskel gave our movie anenthusiastic thumbs-up. (His boob-tube buddy, Roger Ebert, called Carnosaur theworst film of 1993.)

Carnosaur still leaves Adam Simon with a bitter taste in hismouth. When Roger asked Simon to write and shoot his quickie dinosaur epic, Simon took the difficult assignmentbecause he was guaranteed a $3 million budget. Then, three weeks beforephotography commenced, the budget suddenly shrank to $850,000, a figure Simonis now convinced was part of Corman’s plan all along. To make matters worse,when Roger (on the strength of Carnosaur’s success in video stores)spoke to the Hollywood Reporter, he bragged he’d laid out $5 million. A humiliated Simon felt Carnosaur lookedparticularly shoddy if judged by the industry’s 1993 expectations of what $5million can buy. So Simon now regards Carnosauras a cautionary tale for fledgling filmmakers everywhere.

Jurassic Park” and “Carnosaur”: When Dinosaurs Galumph Down Memory Lane

Thirty years ago this month, thenation held its collective breath, wondering how Steven Spielberg would bringto the big screen Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park, a bestselling novel about dinosaurs runningamok in the modern world. And what was I doing around that time? Along with othermembers of Roger Corman’s creative staff, I was patting myself on the back,overjoyed that we at Concorde-New Horizons had managed to scoop Spielberg. Notin terms of lavish production values, of course. Hardly endowed withSpielberg’s access to CGI technology. we had managed to come up with only asingle tyrannosaurus. Roger decreed that it be eighteen feet tall, thusout-Spielberging Spielberg. But the ceiling of our rather make-shift Venicestudio was only sixteen feet high, so the height requirement had to go.

It all began while theCrichton novel (first published in 1990) was being transformed into a motionpicture. Always quick to sense the national pulse, Roger set aside a projectdramatizing the bloody L.A. civil uprising of 1992 in order to bring his owndinosaur movie to the screen. Our mandate: to get our film into theatres beforeJurassic Park opened, thus luring in viewers who couldn’t wait a momentlonger to watch rampaging dinosaurs First, of course, came the script. Rogerpurchased a novel by the Australian sci-fi novelist, John Brosnan. A man whoknew how to make a buck, Brosnan had published back in 1984 a novel called Carnosaur,under the nom de plume Harry Adam Knight. I read it in the line of duty, looking for plotideas, but didn’t find them in the book’s turgid pages. We at Concorde notedthat the initials of Harry Adam Knight could certainly stand for “hack.” Thisnovel was hack-work, pure and simple. Without question, we needed to start fromscratch. All we kept from Carnosaur was its title . . . and maybe that chicken farm set-up.

Roger hired a bright butspelling-challenged USC film school grad, Adam Simon, to write and direct ourdinosaur movie. Perhaps influenced by the opening of Brosnan’s novel on achicken farm, Adam concocted a story about a mad scientist, working for themysterious Eunice Corporation, who manipulates chicken embryos into futuredinosaurs, the better to undermine the human race. The plotline allowed forlots of gory footage, and we hired a big-name actor for the key role of Dr.Jane Tiptree. While in Jurassic Park young Laura Dern was running fromdinosaurs, we had her mother, Diane Ladd, playing the scientist who stirs upall the chaos. I don’t know if Ladd was the first-ever female madscientist in the movie world, but she was outstandingly creepy. It was largely thanksto her vivid performance that TV reviewer Gene Siskel gave our movie anenthusiastic thumbs-up. (His boob-tube buddy, Roger Ebert, called Carnosaur theworst film of 1993.)

Carnosaur still leaves Adam Simon with a bitter taste in hismouth. When Roger asked Simon to write and shoot his quickie dinosaur epic, Simon took the difficult assignmentbecause he was guaranteed a $3 million budget. Then, three weeks beforephotography commenced, the budget suddenly shrank to $850,000, a figure Simonis now convinced was part of Corman’s plan all along. To make matters worse,when Roger (on the strength of Carnosaur’s success in video stores)spoke to the Hollywood Reporter, he bragged he’d laid out $5 million. A humiliated Simon felt Carnosaur lookedparticularly shoddy if judged by the industry’s 1993 expectations of what $5million can buy. So Simon now regards Carnosauras a cautionary tale for fledgling filmmakers everywhere.

June 23, 2023

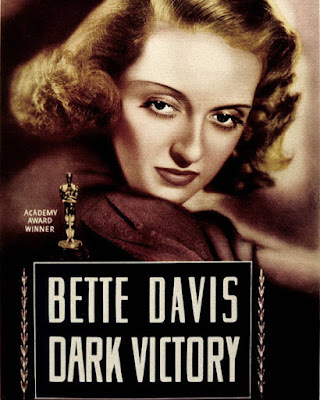

The Eyes Have It: Bette Davis in “Dark Victory”

In 1974, two music industryveterans wrote a song called “Bette Davis Eyes.” Nine years later, the tunebecame a major hit for Kim Carnes, and the 73-year-old diva wrote a letterthanking everyone involved for making her “a part of modern times.” (She also noted that the song had won her newrespect from her grandson.) Davis’s prominent eyes were indeed distinctive.When she was at the height of herfilmmaking powers, young movie fan (and future novelist) James Baldwin overcamehis sense of his own ugliness when he recognized that he too had “Bette Daviseyes.”

Which makes it all the morestriking that “Dark Victory,” one of Davis’s most major screen triumphs, isabout a woman who’s going blind. To be clear, she spends most of the movie withher sight intact, but the threat of blindness hangs over her throughout. What’sthe problem? It’s one of those mysterious movie diseases that I suspect nevershow up in any medical textbook, but there’s a brain tumor involved somehow.Davis’s Judith Traherne is a socialite, headstrong and bold, who suffers aserious riding accident when her vision suddenly fails her as she tries to urgeher horse over a fence. Despite her initial defiant resistance, she allowssurgeon Frederick Steele to operate, and all seems well. But in fact the tumorremains present, and medical experts agree that she’ll soon succumb toblindness and die almost instantly thereafter.

The bulk of the film isdevoted to various characters’ attempts to conceal from one another the fatalprognosis. Out of love, Dr. Steele hidesfrom Judy the deadly truth. Of course she discovers what’s going on, and triesto resist Steele’s marriage proposal, assuming it’s an act of pity. To me, oneof the film’s most dramatic moments is the use of a match struck to light acigarette: Judy’s sudden awkwardnesstells us that she’s experiencing double vision, a symptom of her neurologicalproblem. But I also loved the late section of the film in which Judy—usually astough and egocentric as only Bette Davis can be—is blissfully in love, revelingin a modest domestic life far from her previous haunts. In this part of thestory she seems physically transformed, and her gaiety is infectious. But then,of course, life comes crashing in on her, leading to a heroic but weepyconclusion.

Warner Bros. released DarkVictory (a stage hit for Tallulah Bankhead) in 1939, a year that’s oftentouted as the greatest in Hollywood history. Davis’s Oscar-nominatedperformance was upstaged by Vivian Leigh in Gone With the Wind, andother big films included Goodbye, Mr. Chips, Mr. Smith Goes toWashington, Ninotchka, and The Wizard of Oz. Though DarkVictory won no prizes, Davis has called it her favorite performance.Co-starring with her was George Brent, a reliable but (to me) somewhat stolidactor who played alongside Davis in multiple films and was involved with her ina tumultuous two-year affair. But I was more intrigued by two featured players.None other than Humphrey Bogart plays Davis’s stablemaster, Michael O’Leary. Hewrestles with an Irish accent but aces a scene in which he reveals hisunrequited love for her. (I’m told there was once a final scene of him weepingafter Judy’s demise, but test audiences would have none of that.)

Also aboard is a future U.S.president. Yes, Ronald Reagan is featured as a wealthy playboy He’s alwaysaround in the party scenes and apparently has a yen for Judy but knows that aserious-minded swain like Dr. Steele is more her type.

June 20, 2023

“Empire of Light”: Illuminating the Darkness

Writer-director Sam Mendeshas a gift for portraying wounded souls. And actress Olivia Colman has a giftfor embodying them. In last year’s Empire of Light, a fading movietheatre in a seaside English town becomes the venue in which a lonely,psychologically damaged woman (Colman) suffers great indignity, lashes out witha vengeance, but finally finds her way.

Movies about movie theatresare almost as familiar today as movies about movies. Back in 1924, thewhimsical Sherlock Jr. focused on a projectionist (Buster Keaton) who,pining for a pretty girl, imaginatively willed himself into the movie he wasscreening, transforming his nebbishy self into a bold detective. In The LastPicture Show (1971),. Peter Bogdanovich uses the shuttering of a localTexas movie house to illustrate the slow death of a small town. But the realclassic in this genre is 1988’s Cinema Paradiso, a heartfelt Italiancoming-of-age tale about the formative relationship between a young boy and themiddle-aged projectionist at a local theatre.

Empire of Light also takes us into the projection booth, as a newemployee learns the ropes from a dedicated veteran (Toby Jones). But Colman’s character,Hilary, who functions with great efficiency as the theatre’s manager, rarely watchesa film herself.. She may connect emotionally with the theatre building’slong-ago grandeur, and chooses the night of a major local premiere (Chariotsof Fire) to strike out against someone who deserves it, but it’s rare for her to sit and be transportedby the magic of cinema. It’s only late in the film, when she’s seen the worstof what life can do, that she asks the projectionist to screen a film just forher. Her choice was to me somewhat unexpected: Peter Seller’s melancholy 1979tour de force, Being There. er Her choice

Empire of Light is set in the 1980s, and one part of the social worldit depicts is the era’s common right-wing hostility to Black immigrants. Thoughthe cinema employees are mostly a welcoming lot, a new young Black hire,Stephen (Micheal Ward), has to face up to vicious skinhead types who would beall too happy to do him physical harm. He’s a young man, the son of a localnurse, who’s betwixt and between: he’d like to go to college to pursue a degreein architecture, but he’s pretty much given up on that expensive dream. Somehowhe connects with Colman’s Hilary over a wounded pigeon and the old theatrebuilding’s picturesquely empty upstairs salons. The Hilary/Stephenrelationship—part familial, part sexual—gives pleasure to them both. But ofcourse it is doomed not to last. They are simply too different from oneanother, and too caught up in their own problems to take on someone else’s.

So there’s no happy ending?Well, let’s say that progress is made on all fronts. Friendships survive, andthe old theatre (played in the film by an actual historic cinema that’s nolonger in service) continues to use beams of light to project moving images onto a screen. It’s magic, inmore ways than one.

Sam Mendes segued fromacclaimed work on the British stage to an Oscar-winning American movie, thepainfully sardonic American Beauty (1999). His subsequent films haveincluded a crime thriller, Road to Perdition, a James Bond classic, Skyfall,and a much- honored World War I epic, 1917. Empire of Light returns himto the role of writer-director of an intimate but powerful small-cast film.Though it doesn’t pack nearly the punch of American Beauty, it’s worthseeing (and admiring) in its own right.

June 16, 2023

John Sayles: A Man for All Genres

Mygood friend Frances Doel (hi, Frances!) was the one who brought John Saylesinto movieland. Having read Sayles’ lively stories in classy magazines like TheAtlantic, she suggested him to Roger Corman as a potential screenwriter. Saylestook to low-budget filmmaking immediately, crafting the hilariously lethal Piranhaand the space opera Battle Beyond the Stars. (The latter, a sort ofcheapie Star Wars clone, was alsothe launching pad for another future director, James Cameron.) Everyone knewfrom the start that the multi-talented Sayles aimed to direct: he spent muchtime on the set, soaking up everything he could about how movies were made.

WhenI spoke to Sayles for my Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-EatingCockroaches, and Driller Killers, he told me how much his New WorldPictures years had taught him about Filmmaking 101: “When do you need suspenserather than action? When do you need comedy to give people a break from thesuspense? That’s what I found that Roger and Frances were very good at.” Healso discovered how to write for a Corman budget, and how to approach a scriptin terms of its marketable elements (“How could you advertise this film?”) Heput all this to use in 1980 when he had accumulated $40,000 to invest in hisdirectorial debut, Return of the Secaucus 7. This was, in Sayles’ words,a film in which “I started with very little money, and said, ‘What can I dowell?’ ”

Secaucus7, a college reunion story often seenas a precursor to The Big Chill, revealed Sayles’ longstanding interestin social groupings. When I think of Sayles’ career, I tend to remember Matewan(1987), City of Hope (1991), and Lone Star (1996), toughdramas focusing on complex interactions in periods of political and economicstress. But Sayles can also be darkly satirical, as in The Brother fromAnother Planet (1984), wherein a dark-skinned alien (Joe Morton) lands onearth and tries to fit in.

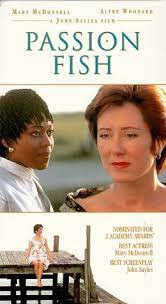

Irecently visited two Sayles films from the 1990s which may seem out ofcharacter, but reveal his skill with actors and exotic landscapes. PassionFish (1992) is very much a female film, influenced by Ingmar Bergman’s Persona.It features longtime Sayles favorite Mary McDonnell as a soap opera starwho, after a serious accident, has been left a paraplegic. Returning to herfamily home in rural Louisiana, she wallows in self-pity until a no-nonsenseBlack caregiver with problems of her own (Alfre Woodward) enters her life. Thestory is by no means saccharine: McDonnell’s character can be bitchy, andHollywood comes in for some well-deserved satirical licks. But it’s adown-to-earth tale of resilience and acceptance, beautifully acted and filmed.

Thebig surprise is 1994’s The Secret of Roan Inish, adapted by Sayles from an Irish novel full of mythological creatures.Sayles’ Ireland is not the cheerful domain of Disney’s Darby O’Gill and theLittle People. Nor is it nearly as black as The Banshees of Inisherin.Roan Inish is a family film, with a young girl as its central character, inwhich terrible things have happened in the past but the ultimate ending isupbeat. Set largely on a mysterious island, it’s surely the most gorgeous filmthat Sayles has ever made, full of water, sand, gulls, and the seals who sharea magical inheritance. I love the fact that it was shot by a late-in-lifeHaskell Wexler, another deeply politicalfilmmaker who set all that aside to revel in the beauty and the folklore of the Irish coast.

June 13, 2023

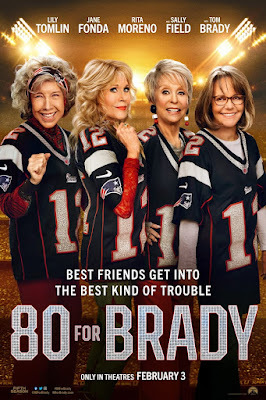

"80 For Brady”: Before Time Passes Us By

On a flight back to L.A.following a trip that was alternatively inspiring and stressful, I was lookingfor light-weight entertainment on my seatback system. That’s why I turned to 80for Brady, a comedy I knew would distract me from the cares of my everydayworld. How could it fail to amuse, given that its cast was headed by some ofHollywood’s most reliable veterans? The combined star power of Jane Fonda, LilyTomlin, Rita Moreno, and Sally Field (not to mention their combined Oscars,Emmys, and other accolades) was sure to divert me from my own anxieties. And soit (mostly) did.

Very loosely based on anactual group of octogenarians with super-sized crushes on New England Patriotsquarterback Tom Brady, the plot features four lifelong friends of a certain agewho stake everything on a trip to Houston to cheer on their hero in Super BowlLI. Of course the differences betweenthe four women are sharply delineated. Trish (Jane Fonda) is a still-glamorousformer beauty queen with a record number of failed romances. Maura (RitaMoreno) is a recent widow whose life in a dead-end retirement home is stiflingher competitive spirit. The youngster of the group is Betty (Sally Field), whokeeps reminding everyone that she’s personally not yet 80. She’s (theoretically)the responsible one: a mathematics whiz whose fellow-professor spouse (BobBalaban) is a bit too clingy for the good of their marriage. Finally there’sLou (Lily Tomlin), whose need for a big adventure at this point in her lifeclouds her judgment, and is the axis around which this story turns.

I always dread movies thatdemean “cute” senior citizens by showing them trying to emulate younger, hipperfolks. And of course there’s some of that here, including the inevitable(sigh!) sequence in which they accidentally trip out on cannabis gummies. And Iwinced when so much of the plot hinges on the search for an essential lost item(yes, I too had just lost something important, which is why this plane trip wasso fraught for me.) Still, there’s fun to be had when the four overcome theworld’s easy stereotypes about the elderly by showing they can dance likechampions, play a killer hand of cards, and emerge victorious from a spicy foodcompetition hosted by TV’s Guy Fieri.

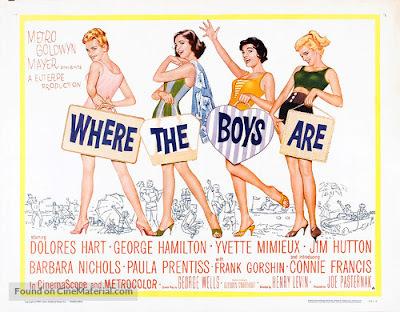

What startled me, inretrospect, was the weird parallel between 80 For Brady and the kind ofmovie my peers and I enjoyed when we were teenagers. One big hit in my juniorhighs school crowd was 1960’s Where The Boys Are. It’s the story of fourcollege co-eds (back then the term was still used) who head south to Floridafor spring break. Of course their #1 goal is romance, and they mostly find it,with very mixed results. The natural leader of the group (Dolores Hart)discovers the kind of love that may last a lifetime. The joker (Paula Prentissin her film debut) finds an equally tall, equally goofy opposite number (JimHutton), and they briefly enjoy a romantic romp. Poor Angie (recording starConnie Francis) never succeeds at love, but she gets to sing the plaintivetitle song, which was soon blasting from radios throughout the country. And themost serious of the plotlines features lovely Yvette Mimieux whose trustingnature leads her into a genuine crisis.

The ladies of 80 for Bradyare mostly not looking for love, or even sex. Their problems are darker:widowhood, the diminishing of personal autonomy, life-threatening illness.Which doesn’t stop them from having fun wherever they can find it.

June 9, 2023

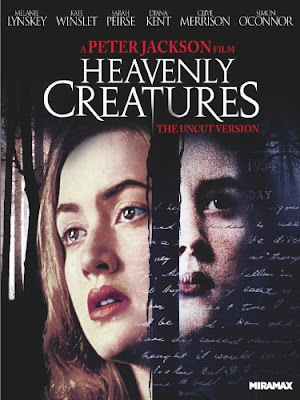

A Helluva Film About Two “Heavenly Creatures”

When a prolific Englishmystery writer named Anne Perry died in L.A. this past April. I didn’t pay muchattention. Then I discovered that, underher birth name (Juliet Hulme), she had been one of the two young defendants ina gruesome 1994 murder trial that set all of New Zealand abuzz. Back in 1954, twoteenaged girls who had met at a tony all-female prep school and become inseparable friends were worried aboutbeing parted when one was sent off to stay with family in South Africa. That’swhy Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme conspired to murder Pauline’s mother incold blood. Because they were both well underage, they escaped New Zealand’sdeath penalty for their crime, but were sentenced to five years in separateprisons. Ultimately each of them left NewZealand, found religious faith (one of them as a devout Roman Catholic, one asa Mormon), and led unexceptional lives.

The obsessive relationshipbetween Pauline and Juliet was captured in 1994 by New Zealand filmmaker PeterJackson in Heavenly Creatures. It was this film that introduced to theworld two actresses, then teenagers, who continue to have an impact on today’s entertainmentindustry. Melanie Lynskey was 16 when she was chosen from among 500 New Zealandschoolgirls to play ugly-duckling Pauline; she has since had a long, richcareer as a character actress in films and on television (Two and a HalfMen, Yellowjackets). Kate Winslet, just a bit older and more experienced asan actress, soon came aboard as the more glamorous Juliet. One year later, shereceived her first Oscar nomination, as well as worldwide attention, for hersupporting role in Sense and Sensibility. (In total, she has racked upeight nominations, winning the golden statuette in 2008 for The Reader.)

Peter Jackson is of coursebest known for fantasy epics, including the masterful Lord of the Rings trilogy.Thinking back to my first viewing of Heavenly Creatures many years ago,I mostly recall the girls’ exuberant but ultimately lethal relationship. Thistime around, I was stunned by Jackson’s stylistic choices, and by the way hehas inserted a fantasy world into a grim kitchen-sink kind of story. (Much ofthis material was taken directly from Pauline’s diaries.) The film, shot inChristchurch at the locations where the killing actually happened, unexpectedlybegins with a kind of Technicolor promotional travelogue detailing the city’scharms: its leafy landscapes, its bustling city streets, its noble-lookinginstitutes of higher learning. The locales we see in the travelogue appear tohave no room for sinister behavior. But soon enough Juliet, the new kid intown, meets Pauline in a stuffy French class, and an obsessive friendship isborn. Juliet, always the leader, includes Pauline in her imaginative constructof a “Fourth World,” a kind of pastoral heaven without the dreary religiousstuff. At times we watch the two girls actually romping through this magicalplace. Elsewhere we see them role-playing the chief romantic protagonists in afairytale kingdom of their own devising. Both girls like to draw and tofabricate items out of plastic, and these later become life-sized human andgargoyle figures that appear, armed with huge swords, in times of stress. Onegargoyle also shows up, most unexpectedly, in a bizarre situation involvingPauline and one of the young male tenants who lodge in her parents’ home. It’sa key sequence that might help explain how far she is willing to go inresisting what she sees as her mother’s oppression.

Prep school life, it appears,is far from prim.

June 6, 2023

Filmmaking That’s Fast, Cheap and Under Control

When I first saw a primer onindie filmmaking called Fast, Cheap and Under Control: Lessons Learned fromthe Greatest Low-Budget Movies of All Times, I was eager to find out whereRoger Corman fit into the narrative. And when I discovered that the openingsection was devoted to Roger and his protégés (soon-to-be famous directors likeFrancis Ford Coppola, Peter Bogdanovich and Jonathan Demme). I was keen to knowwhether author John Gaspard had consulted my Corman biography. Turns out hehad—and credited me as the source of a key Corman-related quote from indiewriter/director John Sayles. So I can give Gaspard credit as a guy who does hishomework. He reads what’s out there to be read, and has also spent countlesshours personally interviewing indie filmmakers, along with those who’ve gone onto bigger and possibly better things. Like Steven Soderbergh, whose majorHollywood career was sparked by the dramatic Sundance success of his indiechamber piece, sex, lies, and videotape.

True to the nature of itssubject, this is a low-rent book. Let’s put it this way: the book is so cheap thatmy copy lacks page numbers. And, though Gaspard gives thanks to a copy editor,there’s an egregious grammatical error on the very first line of the very firstpage. So English majors like me might feel some dismay. Still, there’s a verygood education to be had within these covers, both for those who want to makelow-budget films and those curious about the kind of wildly inventive cinemathat doesn’t require millions. Happily, Gaspard has a great appreciation for smallfilms, whether they are classy stylistic experiments (John Cassavetes’ Shadows)or gruesome horror flicks (The Night of the Living Dead) or outrageouscomedies that make a virtue out of cheapness (e.g. the clopping coconut shellsthat simulate horse hooves in Monty Python and the Holy Grail). Onesection is devoted to science fiction on a budget, another tomock-documentaries like The Blair Witch Project, a third to the growingfield of digital “filmmaking.”

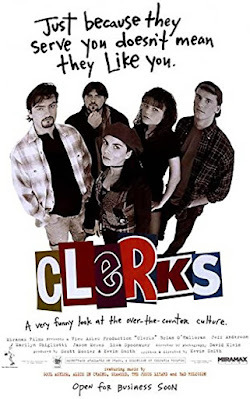

I particularly enjoyed thetips from ambitious upstarts like Kevin Smith (Clerks) and Jon Favreau (Swingers),who explain in detail the writing and directing choices they needed to make inorder to stay on schedule and within budget. For instance, Smith’s one-set filmtakes place in daylight hours in a rather seedy convenience store. But earlyon, a leading character who plays the counter man gripes that the store’sblinds are stuck shut, which means that, along with other workday annoyances,he has to do his job in semi-darkness. There’s a reason for this: Smith wasactually shooting after the store closed for the night, and didn’t want to giveaway the fact that there was no sunlight outside the windows. In Swingers,Favreau (directing himself) looks longingly through a batch of photos of a lostlove, instead of the usual Hollywood flashback to happier times. Such necessarymeasures often breed creativity. Longtime indie director Henry Jaglom (Someoneto Love) quotes to Gaspard a lesson he learned from the great Orson Welles:“The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.”

I was pleased at theinclusion of Dark Star, a USC student film that gave John Carpenter astart as a Hollywood director of sci-fi and horror by using such inventivetricks as making an ordinary beachball into a space alien. My future husbandworked on that film, creating a good-looking space console out of plastic junk.Carpenter borrowed $50 from Bernie and promised screen credit. Eventually hegot neither. That’s another way to save money.

June 2, 2023

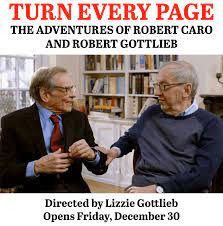

“Turn Every Page”: Robert Caro vs. Robert Gottlieb

The film opens with a soundmany people today have never heard. But I remember it well: the clacking oftypewriter keys. These keys are being struck, in rapid succession, by twofingers, one on each hand. After 87 years of life and the publication of two best-sellingbiographies (one in four volumes, with a fifth on its way), Robert Caro has notyet discovered either computerized word processing or touch-typing. Writing indepth about Robert Moses and Lyndon B. Johnson, Caro sticks to the old ways,including carbon-paper copies of all his drafts.

In his long, illustriouscareer, Caro has always worked with one editor: the now 92-year-old RobertGottlieb. He is by no means Gottlieb’s only prize author: Gottlieb has overseenthe publications of such luminaries as Toni Morrison, Joseph Heller, DorisLessing, and Bill Clinton. But his relationship with Robert Caro seems to be aspecial one, though it is not all smiles and pats on the back. As Gottliebexplains it, “He does the book work, I do the clean-up, and we fight.” Partlythey fight because Caro, an obsessive researcher who started out as a newspaperman, turns in drafts that are many thousands of words over their contractuallimit. That’s why Caro lugs his massive drafts into Gottlieb’s New York office,where together (always with a pair of #2 wooden pencils) they wrestle each bookinto submission.

This is what we see on screenin the new documentary, Turn Every Page, It was shot over five years byGottlieb’s filmmaker daughter, Lizzie Gottlieb. But despite her close proximityto her father and his most famous client, Lizzie did not get total access totheir working relationship. Yes, they are separately candid in answering herquestions (says Gottlieb admiringly about Caro’s accomplishments, “Anyone canbe adorable but not everyone can be industrious—with good results”). But the two men steadfastly refused ever tosit for an on-camera interview together. It was only near the end of thefilmmaking process that Lizzie was allowed to film them working—emphaticallychanging words and x-ing out rejected passages. In those scenes we’ll neverknow exactly what they were saying, because she was expressly forbidden torecord sound.

We do learn, though, a greatdeal about Caro’s research process. A strong believer in conveying the impactof place on a biographical subject’s life story, Caro long ago persuaded wifeIna to move with him to the impoverished Texas hill country, all the better tosoak up the atmosphere in which President Lyndon Johnson was raised. Thishelped particularly when he conducted a key interview with Johnson’s brother,Sam Houston Johnson. Though he had interviewed Sam Houston several times beforeabout his brother’s childhood, Caro distrusted the results. Aside from adrinking problem, Sam Houston had a reputation as a spinner of tall tales. But followinga religious conversion and a period ofsobriety, Sam Houston was persuaded by Caro to be interviewed inside the oldfamily home. Caro seated him at the well-worn Johnson dinner table, then stoodbehind him, frantically taking notes as the man—encouraged, surely, by theonce-familiar surroundings—began to reminisce. This, of course, is exactly whatCaro was hoping for. I’m only amazed that he trusted to his notetaking (and nota pocket tape recorder) to get it all down.

Caro told Lizzie that allthose carbon copies of his drafts were stored in a kitchen cupboard. Near theend of her film, he opens the cupboard door : thousands of sheets of paper arestuffed inside. Who knows what additional treasures they contain?

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers