Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 20

November 21, 2023

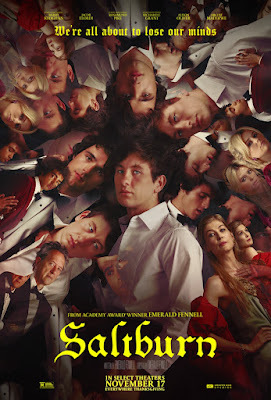

“Saltburn” and “The House of Sand and Fog”: Location, Location, Location

It’s perhaps appropriate thatone of Emerald Fennell’s major acting credits is the role of Camilla Parker Bowlesin the Netflix miniseries The Crown. There’s something entirely aptabout a woman with a yen for the perverse playing a real-life Englishvillainess, opposite Emma Corrin’s dewy Princess Diana. As a writer/directortoo, Fennell seems to gravitate toward the ominous and the grotesque. Her firstfeature as a director, Promising Young Woman, is an often-macabre filmabout a revenge fantasy that becomes all too real. In 2021, it wowed criticsand audiences (and me), landing five Oscar nominations, including Best Picture.Fennell herself was singled out for two nominations, for Best Director and BestOriginal Screenplay. She took home the golden statuette for the lattercategory. I discovered she’d also played a tiny role in the film, as theuncredited host of a Blowjob Lips Make-Up Video Tutorial.

Moving on from that triumph,Fennell has now given us Saltburn, a film seemingly made for those who’denjoy tearing wings off of butterflies and torturing puppies. When I watched itin a large L.A. auditorium, it elicited nervous giggles and guffaws, but I’mnot sure the audience was having fun. We knew from the start that despite thefilm’s cheery Oxford opening scenes there were going to be gloomy times ahead.For one thing, the film’s central character is played by Barry Keoghan, whotook an ominous role in The Killing of the Sacred Deer and was thepathetically lovelorn young man who comes to no good end in The Banshees ofInisherin. Small, pockmarked, and dour (though he has lovely blue eyes),Keoghan plays Oliver, a brilliant but lonely new student who’s taken under thewing of the gregarious and gorgeous Felix Catton (Jacob Elordi). When a familytragedy for Oliver evolves into an invitation to spend the summer at Felix’sfabulous country estate, we think we know where the movie is going. Turns outwe don’t.

Yes, we’ve all seen films inwhich a stately home plays a central role. Think Downton Abbey, Gosford Park,even Rebecca’s Manderley. We’re primed to feel sorry for the outsiderwho just doesn’t fit into the world of wealth and privilege, with its sneeringbutlers, fancy dress balls, and portraits of princely ancestors in thehallways. But as matters get more and more grotesque, we’re no longer sure whodeserves our pity. I suspect Fennell enjoys our confusion, because the cluesdon’t exactly add up. She’s more interested in dark jokes, like Oliver skulkingthrough a Midsummer Night’s Dream-themed birthday celebration wearing an embroideredjacket and a pair of antlers on his head (he’s horny, get it?). And of courseOliver’s intimate involvement with the Catton family leads to a cruel finalTwist.

There aren’t any jokes at allin House of Sand and Fog, a brilliantly executed 2003 drama that centerson home ownership. The house in question, located in a seaside community nearSan Francisco, was inherited by Cathy (Jennifer Connelly), who’s dealing withmarital and drinking problems. When sheloses the house through some sloppy county legal errors, it’s quickly purchasedby an exiled Iranian colonel (Ben Kingsley) and his family. Cathy vows revenge,and is helped by a married deputy sheriff who falls for her in a big way. Thisis a heart-breaking tale in which everyone (mostly) means well, but no onecomes out well in he end. The story, based on an Andre DuBus III novel, iscomplicated but never confusing. And if you’re human, you might shed a tear ortwo for the fools these mortals be.

November 17, 2023

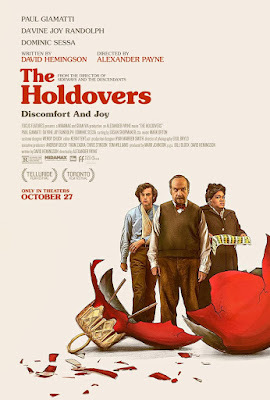

School Daze with The Holdovers

I’m someone who has only a small degree oftolerance for Christmas music. Two weeksbefore Thanksgiving, I used up my entire 2023 quota (“The Little Drummer Boy”! BabyJesus songs!) watching The Holdovers. Not that this newest AlexanderPayne film is all sweetness and light; Payne’s cynicism about the way folkscope with the human condition undercuts the saccharine nature of his score. ButI’m still trying to decide how I feel about this latest entry in theboys-at-a-boarding-school genre. (Think Rushmore, The Dead Poet’sSociety, A Separate Peace . . .) The reviewer at the New York Timesadored The Holdovers, using it as a jumping off point for his own verymixed personal memories. The reviewer at the Los Angeles Times hated it,accusing Payne of insincerity, and worse. Me? I found it appealing in its bestmoments and over-calculated in its worst. I liked these characters, butcouldn’t bring myself to accept their reality.

Paul Giamatti, who shone inPayne’s 2004 Sideways, is something of a specialist in playing morosemen who can’t quite accommodate to their own time and place. Somewhat like thelate Wilford Brimley, he seems never to have been young. As a hapless wineconnoisseur in Sideways, he came off as emphatically middle-aged when hewas still in his thirties. Now he’s aged into the role of a longtime teacher ofancient history at a tony New England prep school where most of the boys (intheir jackets and ties and floppy 1970s hair) have grown up expectingwinter-break Caribbean vacations and easy coasting into Ivy League colleges.(Giamatti, the son of a former president of Yale who later became theCommissioner of Major League Baseball, has had his own prep school experience,so he knows the drill.) In The Holdovers he’s fitted out with a cuttingwit, a secret sorrow, and a series of small physical afflictions that make himunpleasant company to just about everyone. There is about him from the start,though, a quiet sweetness that I wasn’t expecting, especially in his treatmentof the campus’s few women.

One of them, Mary Lamb, isthe head of the school’s cooking staff. Like Giamatti’s Paul Hunham, she’s stuck oncampus during winter break. And she too has a sorrow, though it’s hardly asecret: her only child, a highly promising graduate of the school, has justbeen killed in Vietnam. As movingly played by Da’Vine Joy Randolph, Mary isboth sweet and sour: happily, the script doesn’t allow her to be merely asad-faced bereaved mom. The Vietnam angle does take us by surprise, becausethere’s little sense that this story is set back in time. But perhaps that’saccurate: on this campus, among these well-parented young men, an overseas waris hardly top of mind. Hell, no—they have no intention of going . . . and theirparents will see that their draft boards stay far, far away.

Thethird member of the trio left behind at Christmas is a first-time movie actorwho makes an impressive debut here. Dominic Sessa, an actual prep school grad(class of ’22) plays the classic smart but angry kid with no friends and nofamily to rely on. Naturally, he and Mr. Hunham develop a prickly butunmistakable bond, one that will take an unexpected turn late in the film. I’ma bit Scrooge-ish about the outcome, but Payne’s sympathy for the walkingwounded remains very much intact. (There’s one more such character in the filmthat I deliberately haven’t mentioned, but suffice it to say that Payne is verywell-named.)

November 14, 2023

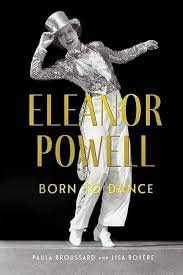

Tripping My Way Through “Eleanor Powell: Born to Dance”

“Nice” doesn’t make youfamous. It doesn’t sell copies of magazines or get you invited to appear on TVtalk shows. Ron Howard, for one, has spent much of his adult career dodging the accusation that he’smerely a nice guy. But Paula Broussard and Lisa Royère have devoted their firstbiography to a woman who balanced star power with a personal graciousness thatmade her a joy to be around. They should know. When That’s Entertainment introducedthem to Eleanor Powell (who starred in glossy MGM musicals from 1936 to 1943),the two fell in love with her spectacularly athletic tap-dancing. Dance-madthemselves, they managed to befriend the long-retired Powell, and were charmedby her friendly and upbeat manner. And yet their dream of compiling a pictorialguide to Powell’s films was put on hold for decades. It was the pandemic thatrevived the project, which then evolved into a fully-researched new biography, EleanorPowell: Born to Dance.

Powell’s early life, welearn, was not an easy one. Raised in tight circumstances by a single mother,she discovered in dance a way to overcome her shyness. At an early age she made it to the Broadwaystage as a variety performer. Though shefirst specialized in ballet and acrobatics, she eventually learned to tap, andthis became her springboard to Hollywood. Before reading Born to Dance Ihad never considered the importance of tap-dancing in early Hollywood musicals.In the decade after sound entered the picture, audiences thrilled to therhythmic clatter of tap shoes on a soundstage floor. In a series of BroadwayMelody films, as well as such starring vehicles as Rosalie, Honolulu, andBorn to Dance, Powell thrilled audiences with bravura production numbers(like dancing down a series of oversized drums) while also performing romantic duetswith the likes of James Stewart and Robert Taylor.

Of course audiences clamoredfor her to be paired with the greatest of male ballroom dancers, Fred Astaire.According to Broussard and Royère, the self-critical Astaire resisted for quitea while the opportunity to be her dance partner. Finally it happened. In BroadwayMelody of 1940, a sentimental tale of two hoofers and the woman who comesbetween them, they wowed audiences with Cole Porter’s “Begin the Beguine,” in what has been called the greatesttap sequence in the history of Hollywood. Performed on an elaborate mirroredset, it begins with a mood of Latin elegance, then shifts midway through intojoyous jazz. Alas, though audiences hoped for an encore,it was not to be. Amazingly, Astaire was intimidated by her powerful tapskills, saying that “I had twenty-nine partners, but I met my match withEllie.”

The end of her partnershipwith Astaire was not the only disappointment in Eleanor’s life. Tastes inentertainment changed, and she faced some health challenges. Her one stab atmatrimony ended in disaster: husband Glenn Ford turned out to be a compulsivewomanizer, and one who also stepped out with men. When they finally divorced,he proved himself a cad about finances, and she was too ladylike to object.Needing to raise son Peter on her own, she courageously resurrected her careeras a nightclub entertainer after years of devoting herself solely to thedomestic realm. Through it all, a strongreligious faith kept her sane.

One truly admirable thingabout Eleanor: she refused to accept skin color as a barrier to friendship. Sheand the great Bill “Bojangles” Robinson shared routines; Robinson and PearlBailey were honorary godparents to her son. A lovely lady, in every sense ofthe word. Brava!

November 10, 2023

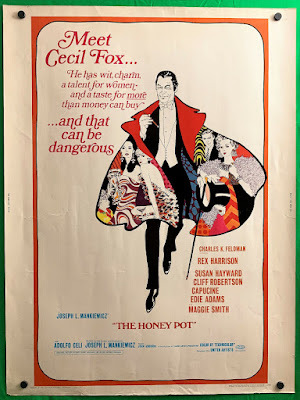

Joe Mankiewicz Sticks His Finger in “The Honey Pot”

The Mankiewicz brothers weregenuine Hollywood legends. Elder brotherHerman co-wrote Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, and literally hundreds ofother classic films, starting in 1926 and ending not long before his earlydeath in 1953. But Herman was something of an underachiever compared to youngerbrother Joseph. Joe (1909-1993) is credited with writing almost 40 films, anddirecting 22. In 1950-1951 he achieved the remarkable feat of winning fourOscars, two for directing and writing the adapted screenplay of A Letter toThree Wives, and two more for writing and directing All About Eve. Henabbed his last Oscar nomination in 1973 for directing his last film, Sleuth.(The expert in all this is my colleague Sydney Ladensohn Stern, for her fascinating2019 study, The Brothers Mankiewicz: Hope, Heartbreak, and HollywoodClassics.)

It was near the end of JoeMankiewicz's fabulous career—which also included everything from the notorious Cleopatrato a documentary on Martin Luther King—that he wrote and directed 1967’s TheHoney Pot. This dark-hued farce, set in a Venice palazzo, has some of thequalities demonstrated by Rian Johnsonin 2019’s Knives Out. In both there’s a lavishly decorated set, acluster of mismatched people, and more than a whiff of murder most foul. KnivesOut boasts, along with a lot of clever business, a subtle and highlyamusing Stephen Sondheim joke. The Honey Pot is even more esoteric,basing its plot on Ben Jonson’s black comedy from 1605, Volpone. As atrue English major, Mankiewicz clearly enjoyed esoteric references to hissource material. His leading character’s surname, Fox, is a clear nod to the“sly fox” of Volpone’s English translation. And Fox’s henchman (Mosca inthe original) is now William McFly. (Get it?)

The crafty Fox is played toperfection by frequent Mankiewicz star Rex Harrison. I’ve heard obnoxiousstories about the real-life Harrison, but in this film he’s delightfullydevious. (Serious hilarity comes from the fact that, as a man obsessed withballet, he madly pirouettes around his home to endless repetitions ofPonchielli’s “Dance of the Hours.” Yes, that’s the piece to which the hipposcavort in Disney’s Fantasia.) Other major players include Cliff Robertson as the sidekick Fox recruitsfor his nefarious schemes, as well as the salty Susan Hayward, the elegant Capucine, and the brassy EdieAdams, all of them playing former loves who are tricked into appearing at Fox’sfake deathbed in hopes of inheriting his fortune. I need a separate mention forMaggie Smith, who also takes part in the macabre festivities, in the role ofHayward’s rather prim and veddy British nurse and companion. In 1967, Smith wasnot brand-new to films. But she was hardly the legendary dowager she has sincebecome in such productions as Gosford Park and TV’s Downton Abbey. Inher early 30s, she was a pretty and rather vulnerable-looking redhead, one whohad just received an Oscar nomination for playing Desdemona opposite ablackfaced (but highly impressive) Laurence Olivier in a filmed version of Othello.Her role in The Honey Pot seems modest at first, but proves to havehidden depths that take us by surprise. Her scenes of give-and-take withHarrison, in which she plays the innocent and he offers a nicely ironicdisquisition on the passage of time, are at the heart of this film.

But all is not perfection. Along with the movie’s wit and such inspired moments as the crafty local police detective watching TV’s Perry Mason dubbed into Italian, there are key plot strands that simply make no sense. Maybe that’s part of the joke too.

November 7, 2023

Black is the Color . . . . Toni Morrison, Shirley Temple, and Blackface On-Screen

I recently saw a dramaticversion of Toni Morrison’s first novel, The Bluest Eye, not on thescreen but on stage. In it, a young African American girl with a grim pastobsesses (circa 1941) over her desire to have blue eyes like her idol, child-starShirley Temple. She’s not the only one in her increasingly tragic family circlewhose life-goals are shaped by Hollywood movies. Her downtrodden mother, itseems, has long brightened her own sad life by admiring such Caucasian stars asClark Gable, Jean Harlow, and Hedy Lamarr on the silver screen. Tellingly, shehas named her daughter Pecola, closely mirroring the name of the young Blackgirl who successfully—though painfully—passes for white throughout much of 1934’sImitation of Life.

Funny thing about Pecola’sobsession with Shirley Temple’s blond-and-blue-eyed charms. Though Temple, whostarred in black & white films in the 1930s and ‘40s, was truly an adorabletyke, her hair was on the auburn side and her eyes were emphatically brown. ButPecola, longing to be a little white girl, naturally assumes that her idol hasbig blue eyes, unlike her own. There’s something about the power of movies thatshowcases our dreams of what we’d like to be, particularly if those dreams arewholly out of reach.

On the other hand, back inthe 1930s and 1940s there are many screen entertainments that highlight whiteperformers posing as Black for public amusement. There was an era when it wascontroversial indeed for a Black performer to be injected into a white cast,even when playing a so-called “tragic mulatto.” As late as 1951, when LenaHorne sought to play the tragically bi-racial Julie in an upcoming version ofEdna Ferber’s hit, Show Boat, she was rejected in favor of thenot-Black-at-all (and not-musical-at-all) Ava Gardner. It was OK for WilliamWarfield, in the role earlier made famous by Paul Robeson, to sit on the dockand sing “Old Man River.” But it was definitely NOT OK for a light-skinnedAfrican American woman to be shown in a love relationship with a white man.

Still, white performers ofthose eras seemed perfectly comfortable smearing on blackface makeup andpretending to be “colored.” This had been happening since the era of D.W.Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), when all the rapacious Blackmen who trash democracy and menace heroine Lillian Gish were portrayed by whiteactors. Later it was common for musical performers like Judy Garland and MickeyRooney to do a blackface minstrel-show turn, as they did in 1941’s Babes on Broadway, completely withJudy’s hair in “pickaninny” braids. In1936, the great Fred Astaire—playing a nightclub performer—darkened his facefor “Bojangles of Harlem,” designed as a tribute to Black tap dance legend BillRobinson and also to Astaire’s friend and mentor, John Bubbles, whose dancingsilhouette—I’m told—backs Astaire’s on screen in this number. I’m sureAstaire’s intentions were of the best, but today such moments can make uscringe. That’s how I felt when watching the otherwise frothy Holiday Inn (1942),in which Bing Crosby’s character establishes a country inn and nightclub whichbuilds its floor shows around holiday themes. The President Lincoln’s birthdaynumber, “Abraham,” features not just Bing (looking like Uncle Remus) and butalso an entire dance band and chorus in blackface, with co-star MarjorieReynolds forced to model exaggerated lips and a particularly obnoxious get-up. (Onecurious note: a cutaway to lovable Louise Beavers as the inn’s cook; she wasearlier the mother of Imitation ofLife’s “tragic mulatto” child.)

November 3, 2023

Suddenly, Last Summer, Elizabeth Taylor Goes Crazy (Or Does She?)

I well remember an early adcampaign, featuring a drawing of a young, svelte, and very beautiful ElizabethTaylor, kneeling in a white bathing suit. She looks anxious, and the words ofthe ad make it clear why: “Suddenly, last summer . . . Cathy knew she was being used for somethingevil.” This was how Hollywood tried tosell an expanded film version of a lurid but poetic Tennessee Williams one-actplay dealing with insanity, homosexuality, and (yes) cannibalism.

Williams, who’d opened theplay on Broadway in 1957, had no say in the making of the film. It was directedby Joseph L. Mankiewicz (whose credits included All About Eve) from aGore Vidal screenplay. The central trio of actors included ElizabethTaylor—then at the height of her dramatic powers and personal notoriety—as wellas a fifty-year-old Katharine Hepburn and a very troubled Montgomery Clift. Theactor was barely recovered from a serious auto crash that mangled his face andleft him dependent on pills and alcohol, but Taylor, who was a close friend,insisted he keep the role. As it turns out, Clift is both the least convincingand the least interesting of the three central characters.

The best word for the basicstyle of this film is “histrionic,” but I mean this as a compliment. Though there’snothing remotely realistic about the situation at hand, there’s somethinggorgeously stylized about the world of this movie and its characters. Settingsinclude a lurid insane asylum and a DeepSouthern mansion surrounded by acres of tropical plants, some of them deadly. Thefilm opens on a lobotomy performed by Dr. John Cukrowicz (Clift), a pioneer inthe field of psychosurgery who cures mental patients of what ails them byremoving part of their brains. He’s summoned by a wealthy and imperious widow namedViolet Venable (Hepburn), who wants to fund a major expansion of his hospitalas a monument to the memory of her dead son, Sebastian. The only catch: he mustfirst lobotomize her troubled niece (Taylor), who has been saying disturbingthings ever since witnessing Sebastian’s death in a Spanish seaside town withthe ominous name of Cabeza de Lobo.

In true Tennessee Williamsstyle, the two female characters express themselves in long soaring monologues.Mrs. Venable talks at length about her special closeness to Sebastian, a youngman of talent, strong emotions, and a disdain for anything he considers commonor ugly. Given the public mores of the 1950s, there’s something the film cannotacknowledge frankly: that Sebastian was destroyed while on the prowl forhomosexual love. Still, you can hardly miss the subtext. It is Taylor’s ownpowerful monologue, late in the film, that makes clear how his violent andintensely symbolic death came to be.

I watched this film afterreading (and blurbing) an advance copy of my colleague Matthew Kennedy’s ElizabethTaylor: An Opinionated Guide, an upcoming publication from OxfordUniversity Press. Kennedy quotes director Mankiewicz as calling Taylor’sperformance here “one of the finest pieces of acting in any motion picture evermade.” Speaking of that climactic monologue, Mankiewicz described it as “anaria from a tragic opera of madness and death.” Though Kennedy himself seemsslightly less enthusiastic about this particular Taylor film role, he doespraise her work in the lengthy monologue as “a wonderment of technique” by aperformer who is “inherently cinematic.”

One of the plants in VioletVenable’s garden is a Venus flytrap, which must be fed flies on a regularschedule. What a multi-pronged visual metaphor for this exotic, unnerving film!

October 31, 2023

Another Sort of Contagion that’s not COVID: “The Thing”

Once upon a time, JohnCarpenter was not well known. As a grad student studying at the USC school ofcinematic arts, circa 1974, he was working on a 16mm thesis film with an outer-spacesetting. Most of the action took place in the cockpit of a deterioratingstarship searching the cosmos for unstable planets. The bargain-basement budget(about $6000) of the original Dark Star was part of its charm. It wasfunny enough, and appealing enough, to catch the eye of Hollywood’s money men. That’swhy the student film, following some major edits, was turned into a commercialfeature, and Carpenter’s professional career was born.

I focus on Dark Star becausethe guy to whom I’m married still bears a small grudge. As a young engineerwho liked to tinker, he was persuaded to build the console of the movie’scommand center out of craft-store plastics and electrical switches. His efforts were much appreciated byCarpenter, who promised him a screen credit for his efforts. He also lent theproduction $50. You guessed it: once Carpenter went Hollywood, the promisesdidn’t get kept. This despite the fact that once he launched a little moviecalled Halloween in 1978, Carpenter was the hottest thing going in thehorror genre.

But Carpenter’swell-documented stinginess shouldn’t detract from his talent. Horror is hardlymy favorite genre, but—with Halloween approaching—I couldn’t resist checkingout one of his creepier efforts, 1982’s The Thing. This film, as Idiscovered, was hardly an instant hit. Critics were harsh (the Los AngelesTimes called it "bereft, despairing, and nihilistic,” while Newsweeksaid it lost drama by "sacrificing everything at the altar of gore”). Audienceswere no more kind. Though Carpenter’s career suffered, the film eventuallyfound hordes of new fans on video. I agree that it’s grim, but also highlycreative, with eerie visuals that won’t let go of your imagination.

The origin of The Thing wasa novella called Who Goes There? that first made it to the screen in1951 as The Thing from Another World. Seeing it as a boy, Carpenter wasfascinated. Then he read the originalversion, which posits that an extraterrestrial life-form has come to earth toassimilate, then imitate, other organisms, including dogs and people. As aresult of this otherworldly invasion, men who encounter “the thing” are turnedinto horrible globs of protoplasm who still bear the remains of humancharacteristics. Part of what fascinated Carpenter, obviously, is the technicalchallenge of replicating these weirdly evolving and very deadly creatures. Thefilm gives special effects pros like Rob Bottin (a Roger Corman veteran,natch!) the chance to combine chemicals, food products, rubber, and mechanicalparts into gelatinous monsters that sometimes replicate the features of the characterswhose bodies they’ve invaded. A full $1.5 million of the film’s $15 millionbudget went into Bottin’s creature effects.

The other attraction of thisstory is the chance it offers to play out an Agatha Christie-type thriller,with a cast of characters diminishing one by one. The story is set entirely inAntarctica (portrayed here by Alaskan and Canadian snowscapes), among anassorted group of American researchers—a physician, a meteorologist, a biologist, and so on—who live together ina remote waystation. Played by reliable character actors like Richard Dysart,Donald Moffat, Wilford Brimley, and Keith David, they are vividly delineated .. . but it’s never clear who’ll be the next to turn into a monster. We dosuspect that star Kurt Russell will endure, but the film’s bleak ending is sureto take us by surprise.

Happy Halloween! I can’t help mentioning that a new Criterion Shelf blogpostsaluting Roger Corman’s creepy Poe films mentions my Roger Corman:Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers as a “highly recommended”look at the world of Corman.

.

October 27, 2023

Whodunit –and Why? “Anatomy of a Fall”

Having just seen, at longlast, the classic courtroom drama Anatomy of a Murder, I couldn’t resistchecking out a new French film with a deliberately similar title, Anatomy ofa Fall. (In the original French, it’s Anatomie d’une chute).This Justine Trier film, which took top honors at this year’s Cannes FilmFestival, also focuses on a emotionally fraught murder trial. But the emphasishere is less on cunning legal maneuvering than on the complex question ofmotive. Exactly what, we wonder, is behindthe sudden death of a man in the prime of life?

One of the pleasures ofwatching foreign movies is discovering actors for whom you have no priorassociations. The blonde and slightly zoftig German actress at the center of Anatomyof a Fall, Sandra Hüller, was brand-new to me. (No, I never saw Toni Erdmann, for which she wonseveral awards back in 2016.) In the French film she’s a successful novelist who’salso a wife and mom. I sensed that, as portrayed by Hüller, she’s an amiable presence within her picturesquemountain community, coolly self-possessed, someone well suited to shrugging offthe disturbances of domestic life. Her seemingly mild, calm personality tendedto put me on her side from start to finish. I might not have regarded her sounconditionally if I’d seen Hüller’s second film this past year, The Zone ofInterest. She has just received a Gotham Awards nomination for this German-languagemovie, in which she plays the supportive wife of the Nazi commandant ofAuschwitz.

The film critics of the LosAngeles Times, big fans of this film, have noted that it was written by adomestic team: Justine Triercollaborated with her longtime romantic partner, Arthur Harari, on the script.Since the couple has two children together, they are surely well aware of thestresses and strains within even the most successful marriage. They insist theyhave never been tempted to kill one another, but their script contains a keyscene, introduced as a recording in the courtroom, that bluntly underscores theanger that can arise between two marrieds (one a successful writer and one stillstruggling at the craft) who discover they are not always on the same page.

A key character in thetriangle of sorts that is their marriage is their pre-teen son, Daniel. Atragic accident a few years back has left him essentially blind, but despitethis challenge he’s a keen observer of his surroundings. His father’s fatalfall from a window in their rustic chalet’s attic puts Daniel in the terribleposition of having to choose sides. As we learn, Daniel’s parents responded tohis permanent disability in characteristic ways. His father, who deeply felt (unwarranted)guilt about the lead-up to the accident, chose to devote himself wholeheartedlyto the boy, including sidestepping his own ambitions to tutor Daniel full-timeat home. His mother, in line with herpragmatic approach to life,, has been matter-of-fact about his changedcircumstances and has trusted him to make his own way through the crisis. Nowthat Daniel’s father is dead and his mother is on trial for his murder, it’s upto Daniel to figure out (with the help of a dog named Snoop) what he believeshappened. Young Milo Machado Graner shines in this tricky role. He’s a pleasureto look at (where do filmmakers find these beautiful kids?), and when hischaracter takes center stage in that courtroom, he’s more than ready for hisclose-up.

October 24, 2023

Third Time’s Not the Charm: The Godfather, Part III

In 1972, everyone was talkingabout the screen version of Mario Puzo’s The Godfather. Who could forgetthe pageantry, the brutality, Marlon Brando stroking that cat? When awardsseason rolled around, The Godfather was nominated for eleven Oscars, winningBest Picture, Best Actor, Best Adapted Screenplay. (It was a great year formovies. In the Best Director category, Francis Ford Coppola was beaten out byBob Fosse and Cabaret.)

A mere two years later, asecond Godfather film showed up on movie screens. With Brando’s Vita Corleone dead and gone, GodfatherII focused on son and heir Michael (Al Pacino), now a reluctant crime bosstrying to reconcile himself to his new power. Michael’s story in the presentday is interwoven with that of Vito as a young man (Robert De Niro) leavingSicily in response to the massacre of his family. Unusually for a sequel, GodfatherII was perhaps even more admired by critics and audiences than the initialfilm. It was nominated for nine Oscars, and won an impressive six, becoming thefirst sequel ever to be named Best Picture, even though it was up against such masterworksas Chinatown.

You can’t blame ParamountPictures, which had optioned Puzo’s 1969 novel, for wanting to take fulladvantage of its golden goose, even though, after the release of GodfatherII, Coppola considered the Corleonesaga complete. That’s why Paramount hired a string of established writers anddirectors to come up with Part III. Some versions had the Corleones workingwith the CIA in Latin America. One involved a turf war with the Irish Mafia inAtlantic City. In another, Michael Corleone is killed early on, and the entirefocus is on his surviving children.

Some twenty years later, Puzoand Coppola were finally persuaded to return to the project, and much of theoriginal cast signed on. The focus is now entirely on an ageing Michael, stilltrying to balance his criminal activities with a desire to lead a worthy life.It’s striking to see what time has done to the familiar Corleone familymembers. Michael is greying and fighting health problems. His estranged wifeKay (Diane Keaton) has a rather silly new hairdo, and her sadness over the handshe’s been dealt is a bit hard to buy. (Since we’ve all seen Keaton be adorablyaddled in Annie Hall, it’s easy to think she’d face tragedy with ablithe and dithering la-di-da.) Michael’s sister Connie (Talia Shire), whom wefirst met as a jubilant bride in Part One, has been turned by circumstance intoa black-clad angel of death. New characters include Michael and Kay’s grownchildren. Son Anthony, who has turned his back on his father’s murderous ways,aspires to be an opera singer, and his stage debut in Palermo (in an opera thatfeatures Godfather-style violence) provides a nice excuse for the entirefamily to end up in Sicily. Daughter Mary (played by Coppola’s own daughter,future director Sofia) is her dad’s loyal sidekick. Her performance was muchderided back in the day, but the truth is that it’s a thanklessly unconvincingrole. And of course there are lots of thugs, connivers, andassassins-in-waiting. (Watch out if you see a cop or a priest on the streets;he’s probably a killer in disguise.)

What makes Godfather III worthwatching? Coppola is still brilliant at staging public spectacle: a street fair, a night at the opera, aninnocent-seeming place where danger lurks. Palermo and Manhattan both lookgorgeous. And the music—that plaintive trumpet theme—lures us into a story thatmight not be quite worth telling.

October 20, 2023

Anatomy of a Murder: Piecing Together a Heinous Crime

Anatomy of a Murder fascinated me when I was a kid. Not that I ever sawthis 1959 courtroom drama. But the title was intriguing, and I was captivatedby the poster art. Against a lurid orange and red backdrop, it features the fragmentedsilhouette of a crudely drawn human body, with the film’s title sprawlingacross the figure’s legs and torso. This was the work of Saul Bass, the graphicdesigner whose long list of Hollywood credits includes the title sequences fromsome of Hitchcock’s finest: Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho. On the Anatomyof a Murder poster, there were no glamour shots of film’s stars, whoincluded veteran Jimmy Stewart and up-and-comers Ben Gazzara, Lee Remick, andGeorge C. Scott. This was not, clearly, intended as a star-spangled production:the poster was all about the movie.

This movie was the work ofOtto Preminger, an Austrian emigré who had first made his mark in Hollywoodwith classy noirs like Laura (1944). When the studio system was in itsdeath throes, he moved on with great success to independent production. I’mgrateful to film scholar Nick Pinkerton, whose notes to the DVD edition of Anatomyof a Murder include the following: “Preminger didn’t court controversy; hewent steady with it. He frankly depicted heroin addiction in a 1955 screenadaptation of Nelson Algren’s The Man with the Golden Arm. He helped tobust the blacklist by crediting Dalton Trumbo as the screenwriter on 1960’s Exodus.He visited a gay bar in 1962’s Adviseand Consent, tangled with Cardinal Spellman over 1963’s The Cardinal andin Anatomy of a Murder put the [Production Code Administration’s]stock-in-trade, the very idea of euphemistic or insinuating language, ontrial.”

How exactly was language ontrial in Anatomy of a Murder? Wespend much of it in a courtroom, where the proceedings move forward sorealistically that law students cite this movie as one of their favorites.Stewart, as the defense attorney in a murder case, performs his courtroom roleso artfully (beneath an aw-shucks exterior) that we’re rooting for him, eventhough we’re not quite sure that the defendant (Gazzara as a hot-temperedsoldier with an enticing wife) deserves to be let off. In the name of realism,words and concepts are bandied about—rape, woman chaser, panties—that inearlier days would have run afoul of stringent MPAA rules about what can besaid or implied on screen.

Part of the reason the filmseems so real is that its basic story really did happen, in the same UpperPeninsula town where Preminger staged his production. It was made into abestselling novel by a certain Robert Traver, this being the pen name of aMichigan Supreme Court justice who went back into private practice after losingan election, much like Stewart’s character. Partly to keep to the reality ofthe situation, Preminger was inspired to bring in an actual attorney—and afamous one—to preside over the film’s courtroom. He was Robert Welch, asuperstar in that era for taking down Senator Joseph McCarthy in the nationallytelevised Army hearings of 1954.

Preminger too had studiedlaw, as had his father before him. Maybe that’s why he ends his film withambiguity, not with a clear sense of of who’s right and who’a wrong. Says acharacter in another Preminger film, “The truth is what the jury decides.” Thisis a fascinating movie about complicated people whose depths we’ll never entirelyplumb . . . and the unexpectedly jazzy Duke Ellington score has its own enigmaticallure.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers