Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 30

December 6, 2022

“The Menu,” Featuring Dishes Best Served Cold

After the lights came up, I went out and ate a cheeseburger, savoring every last bite. Those who’ve seen The Menu will, I’m sure, understand the implications. Let’s just say that The Menu is about fine dining, taken to a degree that’s absurd, even grotesque. It’s a film that will not be to everyone’s taste, but connoisseurs will find it strange, funny, and horrible. Which is why, on a recent evening, the prime screening at my local multiplex was completely sold out. In an era when many film lovers would rather stay home and watch Netflix, The Menu fills the bill for highly original entertainment.

We all love to eat, and some of us love to cook. Which is why many filmmakers have produced works that focus on the cooking and eating of a meal. One of the earliest I remember is the poignant Babette’s Feast (1987), in which a 19th century French refugee thanks the Danish villagers who’ve taken her in by way of a spectacular dinner. It took me a while to discover the Japanese Tampopo (1985) which approaches the preparation and consumption of food in an affectionate but absurdist light. Director Ang Lee, early in his career, made a 1994 Taiwanese film, Eat Drink Man Woman, in which a veteran chef and his three daughters play out the challenges of their daily lives by way of their weekly Sunday meals Food-making substitutes for love in Mexico’s 1992 Like Water for Chocolate, based on an acclaimed novel. There are many more examples, but I’ll stop with Stanley Tucci’s Big Night (1996), about the emotion that goes into the opening of a family-owned restaurant.

In most of these movies, the cooking and serving of food becomes a way of showing love. Which makes The Menu a film with a difference. If revenge is a dish best served cold, the chill here is palpable, but there’s some flaming emotion as well. Not that this is obvious from the get-go, when a group of 12 beautiful people board a launch that will take them to a tiny island for the meal of a lifetime. Their host is fabled chef Julian Slowik (Ralph Fiennes), who introduces each exquisite dish in loving detail, but also rules his open kitchen like a drill sergeant. Some of the offerings are perversely humorous, like the bread plate that consists solely of tiny dabs of oils and sauces, with no bread in sight. Other courses . . . well, it wouldn’t be fair to say.

Part of what animates The Menu, aside from a desire to tell a helluva good story, is a disdain for the absurdities of today’s fine dining scene, in which small numbers of diners pay exorbitant sums to feast on the rare and the exotic. Some of the targets of the film’s very dark jokes are snobbish restaurant critics, roistering investment bros, burned-out Hollywood celebrities (John Leguizamo at his slimiest), elitist big-spenders, and foodies who live for moments of gustatory bliss. Chef Slowik clearly resents all those who have elevated his culinary reputation by luring him away from simple food, lovingly cooked. In the role, Ralph Fiennes is a marvel as both genius and madman, capable of both utter coldness and surprising warmth. His opposite number is the restaurant’s one unexpected guest, played by Anya Taylor-Joy. Her unusual saucer-eyed beauty seems to make her well-suited to parts in eerie projects like The Witch, Last Night in Soho, and TV’s The Queen’s Gambit. In The Menu she plays a gal who’s more than she seems, and her role here is, well, a whopper.

.

December 3, 2022

No Weeping for the Return of “Willow”

Disney+ is kicking off the holiday season with Willow, a new series, based on an old movie. Back in 1988 (which I’m tempted to refer to as “olden times”), George Lucas persuaded a new young director named Ron Howard to make a fantasy film with a little person at its core. Lucas had, while directing Return of the Jedi, been impressed by tiny WarwickDavis, a three-foot-four-inch bundle of energy who played Wicket the Ewok, among other roles. It was Lucas’s idea to star someone like Davis in a period adventure saga.

Disney+ is kicking off the holiday season with Willow, a new series, based on an old movie. Back in 1988 (which I’m tempted to refer to as “olden times”), George Lucas persuaded a new young director named Ron Howard to make a fantasy film with a little person at its core. Lucas had, while directing Return of the Jedi, been impressed by tiny WarwickDavis, a three-foot-four-inch bundle of energy who played Wicket the Ewok, among other roles. It was Lucas’s idea to star someone like Davis in a period adventure saga. But since Lucas was a shy man who lacked an easy rapport with actors, he had gradually moved into the producer’s role. Howard at that time was still fairly new to movie-making on a grand scale: his Splash(1984) and Cocoon (195) had been mainstream hits, but Willow’s $50 million budget and sizable special effects demands gave him pause. Still, he was eager to work with the tech wizards at Lucas’s Industrial Light and Magic. Moreover, he reasoned that his five-year-old daughter Bryce and his toddler twins (not to mention the little boy on the way) would soon be the perfect age to appreciate big-screen fantasy.

Despite Lucas’s enthusiasm, Warwick Davis was not a shoo-in for the leading role of Willow Ufgood, who is forced by circumstance to journey far from his home among the Nelwyns, a race of little people under four feet tall. A farmer who dreams of becoming a magician, Willow suddenly finds himself entrusted with a full-sized (or “Dakini”) baby. This baby is none other than Elora Danan, whose survival spells doom for the evil Dakini queen, Bavmorda (Jean Marsh). In the course of his travels to return the infant princess to her rightful home, Willow encounters all manner of unlikely creatures: vicious deathdogs, frightening trolls, beautiful fairies, a sorceress trapped in the body of a rodent, and pugnacious brownies nine inches high who make the three-foot four-inch Willow seem like a giant. There are battles and breathless escapes aplenty before Willow uses his budding magic skills, along with his native wit, to defeat Bavmorda and restore the forces of good.

When I spoke to Warwick Davis for my Ron Howard: From Mayberry to the Moon . . . and Beyond, he told me he was somewhat daunted by the demands of the title role. Despite all his experience on Star Wars films, here he would be without a mask and a creature suit, and the range of his emotions within the film would be huge. Howard too was worried about Davis’s suitability, because he was a mere seventeen years old. Not only did the part of Willow call for him to interact with a baby, but his character was supposed to be a loving husband and the father of two young children. Once he won the role, Davis, who had never before lifted a baby, was put through an informal training course on how to care for an infant, diaper-changing and all. Howard also arranged lessons in diction, horsemanship., and sleight-of-hand.

Happily, Disney’s new series returns Davis to the title role. Now a 52-year-old with a long filmography to his credit, he occupies a world in which baby Elora Danan has become a grown woman and a queen, but still relies on Willow’s talents to help her fight off evil.. Long ago I wrote that the original film “is an uneasy blend of life-or-death adventure, heartfelt sentiment, golly-gee wizardry, and comic riffs.” Still, it found many young fans on video, and the well-regarded new series should bring in more.

November 29, 2022

Man Wanted -- "The Postman Always Rings Twice "

James M. Cain can be viewed as God’s gift to American film noir. His fictional works The PostmanAlways Rings Twice (1934), Double Indemnity (1936), and Mildred Pierce (1941) were all adapted into major studio hits, and he had his hand in many other Hollywood projects, like the classic Out of the Past. I admit I have not read Cain’s fiction (though I’m awaiting a library volume to help make up the gap in my pop culture education). So I’ll have to judge Cain by the films made from his prose.

Women in Cain’s world are very beautiful, very smart, and very powerful. As Mildred Pierce, Joan Crawford shows the tough-minded business savvy of a single mom who rises on the social ladder by founding a chain of popular restaurants. In Double Indemnity (1944), Barbara Stanwyck is the classic femme fatale, romancing Fred MacMurray as a convenient way to get rid of her wealthy but unwanted husband. (Billy Wilder, who both directed and collaborated on the screenplay with Raymond Chandler, felt that this was his very best film, and treasured the fact that Cain praised his adaptation.) The Postman Always Rings Twice, filmed in 1946, also contains a wow of a female role. Once again, murder is afoot, but the twists and turns of this story keep the audience guessing.

In Double Indemnity, Barbara Stanwyck makes one of the all-time great movie entrances, gliding down the staircase of a high-class home. The blonde pageboy hair-do, the scanty clothing, the sexy anklet . . . all spell trouble with a capital T. Tay Garnett’s film adaptation of The Postman Always Rings Twice gives us another version of that same entrance. This time it’s Lana Turner at the foot of the stairs leading from the living quarters down into her husband’s luncheonette. She’s clad all in pristine white: white turban, white shorts, white midriff-baring top. No wonder the handsome drifter played by John Garfield looks gobsmacked. When he hands her the dropped lipstick tube that’s rolled across the floor and ended up at his feet, we know what’s coming . . . or we think we do.

What makes Postman so fascinating is that the characters keep changing their minds about what they really want. As Cora, Turner first makes it her business to rebuff her husband’s new hire, harshly telling him to leave town. Her main goal, she insists, is fixing up the lunchroom, and Frank’s salary will only deprive her and husband Nick of needed income. But the amiable Nick, who loves his liquor and trusts his wife, insists that Frank stay on. (Nick, at midpoint, lovingly serenades Cora with a 1931 tune that captures his naïve view of the situation: “I’ve got a woman crazy ‘bout me--she’s funny that way.”)

Of course the inevitable comes to pass. There’s an elaborate plot by the lovers to rid themselves of Nick, but a meddling cat changes everything. From that point forward, nothing ever works out as planned. Even when Nick is finally gone for good, some clever legal shenanigans have Cora and Frank at one another’s throat. The ending is bleak for all concerned, though in a strange way connected with the story’s unusual title, Frank comes to feel at peace with the fact that he’s only getting what he deserves.

I noted, at the outset, that the sign that lures Frank into the luncheonette reads Man Wanted. In both Double Indemnity and The Postman Always Rings Twice, this come-hither call should be construed as a warning. The sirens are singing, and there’s danger ahead.

November 24, 2022

Robert Clary: A REAL Hogan’s Hero

Last week Robert Clary died at the ripe old age of 96. As we celebrate a holiday dedicated to thankfulness and brimming with nostalgia for times gone by, it seems appropriate to salute this pixie-ish Parisian who was so much more than his acting career.

Last week Robert Clary died at the ripe old age of 96. As we celebrate a holiday dedicated to thankfulness and brimming with nostalgia for times gone by, it seems appropriate to salute this pixie-ish Parisian who was so much more than his acting career. I was first aware of Robert Clary because of his role on an improbable hit sitcom (1965-1971) called Hogan’s Heroes, which was one of my father’s favorites. The series, which seemed to tickle those who had served in the U.S. military during World War II, was set in a POW camp behind the German lines. Bob Crane, as the American Colonel Hogan, led a ragtag group of international prisoners (a Brit, a Frenchman, a Black American, a hillbilly) who took delight in sabotaging the German war effort. It was a bit like Billy Wilder’s great Stalag 17 (1953), but in a much more light-hearted vein, with no one coming anywhere close to dying. On a weekly basis, the “heroes” pit themselves against the fuss-budget German camp commander, Col. Klink, and his doofus sidekick, Sgt. Schultz, and hilarity ensues.

Personally, I always found the success of Hogan’s Heroes disturbing. Knowing something about the horrors inflicted by the Nazis upon Jews and others, I was not ready to laugh at them as essentially harmless dummkopfs. (Others, I know, have felt the same way about Mel Brooks’ treatment of Hitler enthusiasts in The Producers. Brooks makes a good case, though, in describing his comic skewering of Nazis as a form of victory over oppressors who’ve gone down in flames.)

Years after Hogan’s Heroes went off the air, I was surprised to learn that Clary—the series’ feisty, beret-wearing LeBeau—was in fact Jewish. Moreover, he had first-hand knowledge of Nazi atrocities during World War II. Clary, then known as Robert Max Widerman, was born in Paris to an emigré couple from Poland, the youngest of 14 children. When he was 16, the family was forced by the Nazis from their cramped but picturesque apartment and herded into cattle cars, bound for death camps. Though his parents were quickly murdered in Auschwitz and most of his siblings also perished, Clary used his musical comedy talents to gain favor and improved rations. On April 11, 1945 he was one of those liberated by General George S. Patton’s Third Army from Buchenwald. Eventually his theatrical skills brought him to the Broadway stage (via the New Faces of 1952 review) and then to television.

Clary was not the only Jewish member of the Hogan’s Heroes cast. Ironically, the series’ two main Nazis were played by Jews who had fled Europe when the Nazis came to power. Werner Klemperer, who won two Emmys for playing Col. Klink, was the son of world-famous orchestral conductor Otto Klemperer. The family left Berlin for Los Angeles, one step ahead ot the Nazis, when Werner was 13. John Banner, who hilariously played the obtuse Sgt. Schultz, was a Viennese Jew who left Nazi-occupied Austria for the U.S. in 1938. I’ve never run across their comments about the comic bad-guy roles they played to perfection. Clary never spoke of his background either, until in 1980 he recognized that—in the face of Holocaust denial by many—he had a moral obligation to speak out. Working through L.A.’s Simon Wiesenthal Center, he became a frequent speaker at high schools and colleges. In 1985 there was the release of a documentary Robert Clary, 85714: the title reflected the number tattooed by the Nazis on his arm.

Despite his past, Clary was never one to look back in anger. All hail!

November 22, 2022

May You Have “A Perfect Day”

Benicio del Toro, Tim Robbins, and a host of international actors I’ve never heard of. Sometimes it’s fun to watch a movie about which you know nothing. That certainly was the case when I aired 2015’s A Perfect Day, directed (and co-written) by in an English-language adaptation from a Spanish novel. With Thanksgiving fast approaching, “a perfect day” seemed like a timely idea.

The day that plays out in this fascinating film is hardly perfect. We find ourselves in a random part of Croatia, where war is splitting apart the former nation of Yugoslavia. In theory, at least, the hostilities are nearly over, but that fact doesn’t call a halt to the random bombings and other hostilities that are pitting neighbor against neighbor. The film’s central players are humanitarian aid workers, some experienced and one brand-new, who are trying their darndest to protect the locals from one another. Crisis #1: a rather large man has been killed and then tossed into a well. It's too late for him, but his decaying corpse is sure to contaminate the villagers’ precious water supply.

The film’s opening credits are, quite dramatically, set against attempts to tie a rope around the body and then hoist it from the well before any more harm is done. Alas—the rope breaks, and the aid workers’ desperate search for a stronger one proves futile. (Locals just don’t trust this international group of do-gooders, even when promised generous compensation.) A kid offers a rope that turns out to be tied to a vicious dog, and before the film is out we’ll find that rope can show up in other disturbing circumstances as well. It will take until the fade-out to solve the problem of the man in the well, and I wouldn’t dream of spoiling the surprise.

The aid workers are led by the crusty del Toro, who dreams of going home, and by the maniacal Robbins, a joker-type who seems to be working overseas because he’ll never make good in the country of his birth. Assisting them is Mélanie Thierry, a French water and sanitation expert who’s brand-new on the job but is already trying to process the viewing of her first corpse. A temporary member of the contingent is Olga Kurylenko, a gorgeous Slav who was once the del Toro character’s lover. (When he notes that she looks different from what he remembers, she wryly notes that now she has clothes on.)

The gallows humor that is laced throughout the film is reminiscent of M*A*S*H, both the 1970 film and the long-running TV series about an American medical unit near the front lines of the Korean War.. The big difference is that these aid-worker characters are on neither side of the conflict. They don’t play favorites: their only goal is to preserve the health and safety of the war-battered people around them. But somehow this ends up meaning that they’re always personally facing danger from angry partisans, booby-trapped cows, and natural disasters exacerbated by the destruction of war. Even the American peace-keeping forces in the region make their work more difficult: military red tape is always stopping them from doing what needs to be done.

As in M*A*S*H, battle-scarred men turn tender when faced with the plight of innocent children. Nikola is a small boy whose concern about a stolen soccer ball turns out to be a cover-up for his anguish over his parents’ fate. He too is gradually absorbed into the aid worker entourage, proving that these wisecracking tough guys do have hearts after all.

November 18, 2022

“The Fabelmans”: Close Encounters with the Spielberg Family

Over the years, I’ve had many lunches at the Milky Way, a dairy café on an ethnic stretch of Pico Blvd. in West Los Angeles. Its proprietor was, until her death at age 97, a pixie of a woman named Leah Adler. She was hard to miss, with her close-cropped blonde hair, her bright red lipstick, and het Peter Pan collars. Until old age caught up with her, she’d literally dance around the restaurant, greeting guests warmly, and making sure everyone knew which menu items were preferred by her famous son.

The movie posters in the lobby, as well as that prominent E.T. doll, told the tale. Leah Adler was the mother of Steven Spielberg, and she wanted the whole world to know it. On one occasion, I even came close to an encounter with the man himself. We’d ordered the cheesecake for dessert, and Leah breathlessly informed us that Steven, seeing it emerge from the kitchen, had declared he was tempted to scoop up a bite with his finger. I looked where she pointed, to an area near the dining room entryway, but could see only the back of a head topped by a baseball cap. So much for star-gazing.

Anyone aware of this unshakeable mother/son bond would be curious indeed about The Fabelmans, a memory film billed as the true story of Steven’s growing-up years. By the time I saw it, I knew something more of Leah Adler, of her musical aspirations as a young piano student, of her domestic eccentricities, of the painful moment when she broke up the family unit. As played by Michelle Williams in a bravura performance, she’s lively, creative, self-promoting, the acknowledged fairy queen of the household. When, on a family camping trip, she dances in the moonlight in her white nightgown, she wins everyone’s heart. (Mine too!)

What I knew little about was Spielberg’s engineer father, here called Burt Fabelman, As played by Paul Dano, he’s a brilliant nerd, in love with his wife, his family, and his work on early computer technology. There’s an amiable cluelessness about him that’s a fresh take on movie fatherhood, but at the same time he reminded me of so many screen fathers –-like Chris Cooper in October Sky—who praise their sons’ intellectual drive but can’t accept their chosen professions.

The young Spielberg clone, Sammy Fabelman, is introduced to movies by both of his parents, with his father focusing on technological achievement and his mother passionately cherishing movies as akin to dreams. When Sam starts to film his own backyard masterpieces, with his little sisters in starring roles, both parents cheer him on. But as he nears adulthood, refining his cinematographic skills and learning to shape the world that surrounds him through the lens of his camera, moviemaking becomes his retreat from the disturbances of everyday life. Ironically it also, in the film’s most crucial episode, becomes his proof of a reality he doesn’t want to face.

My least favorite part of the film strays from the family story to show a teenage Sam enduring anti-semitic taunting while romancing a girl with a Jesus complex. The outcome of that segment reveals Sam using filmmaking as a quixotic way of handling his oppressors, but the romance—funny though it is—seems a rather cheap way of getting some laughs into the picture. For me the film’s highlight is the visit of Uncle Boris (Judd Hirsch), a rather mysterious circus performer who descends on the family at a time of tragedy. It’s he who explains to Sam why the artist always has to go it alone.

November 15, 2022

Rocketman: Jake Gyllenhaal Reaches for the Stars in “October Sky”

Some people’s lives seem just destined to be a movie. Take Homer Hickam, a teenager whose life was unended when—along with other residents of tiny Coalwood, West Virginia—he watched Russia’s Sputnik 1 pass overhead in October 1957. Mesmerized by the possibilities of space travel, he gathered some friends and some rudimentary equipment, then started to experiment with rocketry on a larger and larger scale. None of this pleased his father, a much-respected superintendent at the local coal mine, who expected his son to someday follow in his own footsteps. But the local science teacher, an ebullient young woman, believed in the ambitions of the amateur rocketeers, She foresaw that if they could capture first prize at the county science fair, they would earn a trip to a national convention in far-away Indianapolis. The end result, she hoped, would be college scholarships for four bright lads who (not being good at football) had no other hope of paying for college educations.

There were, needless to say, ups and downs, including a brief tangle with the law when the four were accused of setting off a forest fire with one of their experiments. All of this was set down in Rocket Boys, a best-selling 1998 memoir by Hickam, who grew up to be a NASA engineer charged with training astronauts. He’s covered other aspects of his eventful life in additional books, crafted a Rocket Boys musical, and also tried his hand at writing fiction. Clearly he's a man of many talents, and one who’s also been blessed with a lot of good luck. After all, he could easily have spent his life, as so many of his friends and neighbors did, slogging away in a coal mine. And dying, as his father did, of black lung disease.

When words on a movie screen note that the film we’re about to see is “based on a true story,” we’re always entitled to a certain amount of disbelief. And so I watched October Sky, the 1999 film that evolved out of Rocket Boys, with a certain sense of skepticism. (Sidenote: the title October Sky, which points to the impact of Sputnik passing over that West Virginia town, is an anagram of Rocket Boys. Why? I have no idea.) Though I enjoyed this modest film thoroughly, its story seemed a bit too good to be true. Were the boys of Big Creek High School really taken in hand by a pretty and dedicated teacher, one who was secretly dying of Hodgkin’s Lymphoma? Did Homer’s strict but loving father, who disapproved of his son’s rocketry “hobby,” really stay away from every one of the early rocket test launches, even though the rest of the town turned out en masse to see what the boys were up to? Did that same father finally show up for the triumphant final launch, and find himself given the honor of pushing the button that ignited the rocket? According to Hickam’s own commentary, this is exactly what happened. (By the same token, he encourages fans to read a more complicated version of his story in Rocket Boys.)

The age-appropriate Jake Gyllenhaal—then barely 19--broke into the Hollywood mainstream with his portrayal of Homer. Laura Dern played the inspirational teacher who hides her personal woes from her students. The key role of Homer’s father was played by Chris Cooper, who’s always convincing as a tough but tender blue-collar guy. Other players were unfamiliar to me, but all showed their comfort with an authentic-sounding West Virginia twang. Following your dreams into space: what a nice theme for a family-centric movie.

November 11, 2022

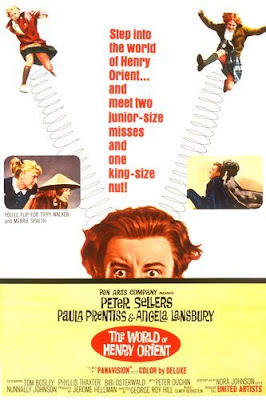

An Oscar (Levant) for “The World of Henry Orient”

While watching some of the great MGM musicals of the 1950s, like An American in Paris and The Band Wagon, I’ve been mystified by the appearance of a sour-looking troglodyte named Oscar Levant in sidekick roles. Levant was not much of a singer or a dancer, but the plots of his movies usually found a way to seat him at a piano, for he was (among many other things) a concert pianist of some note. In An American in Paris, which pays tribute to the musical compositions of George Gershwin, there’s a dream sequence in which he appears—elegantly clad—in a concert hall, not only pounding out Gershwin’s Concerto in F on the keyboard but also playing all the other instruments in the orchestra, while functioning as its conductor as well.

Levant was also a famous wit, one who’d aired his stock of arcane knowledge on a popular radio show, Information Please. It was he who first quipped, “I knew Doris Day before she was a virgin.” But one target of his wit was always his own hypochondria, which was frequently written into his movie roles I never saw this as particularly funny, though moviegoers of his era seemed to enjoy it. They also were amused by his wisecrack that “there's a fine line between genius and insanity. I have erased this line."

While marveling over Levant’s onetime popularity, I heard that he was the inspiration for the neurotic, womanizing pianist at the center of Nora Johnson’s novel, The World of Henry Orient, as well as its 1964 film adaptation. Having just seen that film, I’m not entirely convinced. But it makes sense that the name Levant (which in French suggests the east, the place of the rising sun) could by adapted by Johnson into “Orient.” The film version gets playful with Henry’s exotic surname, with his young-girl fans adopting Chinese coolie hats and performing vaguely Japanese kowtows in his honor.

The World of Henry Orient involves two basic stories that ultimately come together. The first involves two lonely young teenage girls, both enrolled in a ritzy New York prep school, who join forces when they realize that their vivid imaginations and their willingness to pull pranks on strangers make them natural allies. The second concerns a talented but egotistical concert pianist who blithely skips rehearsals because he’d rather be rumpling the sheets with a safely married admirer. When the more musical of the two young girls hears Henry Orient tickle the ivories at the local concert hall, she’s in love. From that point onward, Val and Marian pursue Henry around Manhattan, adoringly spying on his every move, while he grows increasingly paranoid.

With Peter Sellers (in his first Hollywood film) as the pianist, Paula Prentiss as his main squeeze, and a host of filmdom’s best character actors in featured roles, this film is guaranteed to be spritely fun. It’s directed by George Roy Hill at a lively pace, several years before he captured moviegoers’ hearts with Butch Cassidy and The Sting. What I didn’t anticipate, though, was a scene-stealing Angela Lansbury, whose match-up with Sellers is a classic. She’s Val’s egotistical mother, who’d rather tour the world than attend to her daughter’s growing-up years. Accidentally discovering Val’s serious crush on Henry Orient, she marches off to do her motherly duty by confronting him. Then—whoops!—these two narcissists discover they’re made for one another. Which leads to a reshuffling of priorities in which Val’s easy-going father (Tom Bosley) finally takes a leading role. So hilarity and poignancy both contribute to an ending that’s satisfying while still fun.

November 8, 2022

Fingering “The Banshees of Inisherin”

For a good time, DON’T call Martin McDonagh. At least, when attending one of McDonagh’s plays or movies, don’t expect a lot of easy-going fun. McDonagh, a British-born playwright who’s turned into a successful filmmaker, is about as far as you can get from John Ford, another director who was not born in Ireland but retained a strong family affinity for the auld sod. Ford showed his love for the Irish countryside in 1952’s The Quiet Man, a romantic romp in which John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara struggle to get the best of one another. Fighting and feuding dominate the action, but all’s well that ends well.

McDonagh’s plays about hard-scrabble Irish country life end far less happily. (I’ll never forget the finale of The Lieutenant of Inishmore. It’s billed as a comedy; I’ll say only that I’m sorry for whomever has to clean up the stage at each performance’s end.) As a film writer and director, McDonagh has ventured far afield. He went to a Medieval town in Belgium for In Bruges and to the American heartland for Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, which scooped up seven major Oscar nominations, and won statuettes for Frances McDormand and Sam Rockwell. His fourth feature, The Banshees of Inisherin, returns him to a remote Irish village on a rocky isle across the water from where the Irish Civil War is just winding down. Though the island village is far from the shooting, there’s enough anger and confusion in the souls of local inhabitants to fuel some major hostilities. No, they’re not feuding about politics. The fierce emotions that dominate the screen are a simple (or not-so-simple) matter of two men who discover that they can no longer remain drinking buddies and bosom pals. .

The Banshees of Inisherin grew out of the experience of making In Bruges, in which the roles of two antsy Irish hit-men were played to a fare-thee-well by Colin Farrell and Brendan Gleeson. So well did Farrell’s hyperintense Ray play off against Gleeson’s phlegmatic Ken that McDonagh was moved to re-team them in a film about the waning of a friendship. He also worked into his plot Gleeson’s considerable skill on the violin. Gleeson is credited with composing and performing a piece of Irish music that’s essential to the film, and everyone who’s seen it knows how large a role his musical dexterity plays in the unfolding plot.

Viewers should be prepared for a nightmarishingly gruesome element to the story: McDonagh hardly soft-pedals matters that are horrific to watch. There’s also a sad subplot involving a young man who might be described as the village idiot. That being said, many of the moments I remember are comedic ones, growing out of ther personalities of townsfolk who’ve lived their whole lives on a tiny island. Minor characters are as colorful as in a John Ford movie, like the publican who’s seen it all, the priest who doesn’t need the confessional to know everybody’s business, and the shopkeeper who shows no shame when, as acting postmistress, she reads the rare important letter that arrives for one of locals.

The coast of Ireland, as depicted in this film, is a place of rare but stark beauty. The quaint houses, the cozy pub, and the rocky seashore all have a powerful allure, as seen in the brilliant cinematography by Ben Davis, on holiday from his usual superhero flicks. A shout-out to music by the always interesting Carter Burwell and by the eerie portrayal of an ancient local crone, Mrs. McCormack (Sheila Flitton), who’ll show you what a banshee really is.

November 4, 2022

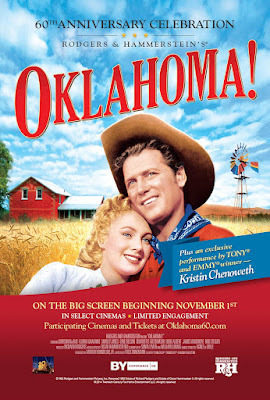

Oklahoma! vs. Woke-lahoma! (The Traditionalist and the Avant-Garde Should Be Friends)

Here in L.A. the recent talk of the town was the edgy new production of an old war-horse that moved from Broadway to the Ahmanson Theatre. Oklahoma!, which launched the musical partnership of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, premiered on Broadway in 1943. It thrilled audiences with its tuneful songs (“Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’”, “People Will Say We’re in Love”) and its hearty dose of Americana. Up until Oklahoma!, hit Broadway musicals were usually loosely assembled collections of musical numbers featuring tuxedo-clad men, beautiful chorus girls, and snappy repartee. Oklahoma! was not the first Broadway hit to delve more deeply into characterization and social commentary. (Show Boat, which dealt boldly with race relations, had been launched back in 1927.) But Oklahoma!’s homespun settings, and its songs written to define character and advance the drama, seemed a fresh new approach during the war years. The show, performed not by Broadway stars but by singers capable of exuding dramatic power, won a special Pulitzer Prize, as well as the hearts of audiences worldwide.

Here in L.A. the recent talk of the town was the edgy new production of an old war-horse that moved from Broadway to the Ahmanson Theatre. Oklahoma!, which launched the musical partnership of Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein, premiered on Broadway in 1943. It thrilled audiences with its tuneful songs (“Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’”, “People Will Say We’re in Love”) and its hearty dose of Americana. Up until Oklahoma!, hit Broadway musicals were usually loosely assembled collections of musical numbers featuring tuxedo-clad men, beautiful chorus girls, and snappy repartee. Oklahoma! was not the first Broadway hit to delve more deeply into characterization and social commentary. (Show Boat, which dealt boldly with race relations, had been launched back in 1927.) But Oklahoma!’s homespun settings, and its songs written to define character and advance the drama, seemed a fresh new approach during the war years. The show, performed not by Broadway stars but by singers capable of exuding dramatic power, won a special Pulitzer Prize, as well as the hearts of audiences worldwide. Today we hardly see what the fuss was about. It’s easy to dismiss as corny a plot that hinges on which swain will buy a pretty girl’s picnic hamper at their town’s box social. And even some of the genuine innovations now seem old-fashioned. For instance, there’s that dream ballet in which a stand-in for the show’s leading lady dances out her romantic uncertainties through Agnes de Mille’s artsy choreography.

The dramatic ambitions of Hammerstein’s book hinge on the show’s strangest element, the handling of a character named Jud Fry. He’s a hired hand with a yen for Laurey, who’s clearly much more interested in a rakish cowboy named Curly. Scruffy and taciturn, with a taste for pornography, Jud is no one’s dream date. He’s treated with contempt by Curly (who encourages him to kill himself), and sneered at by everyone else. The new production that picked up Tony Awards in 2019 leans into the mystery of Jud, and why Laurey allows him to drive her to that box social. The whole section of the show involving Jud becomes intense and steamy, complete with a psychosexual dream ballet that is hardly as genteel as Agnes de Mille’s. And the interracial cast in the touring production features a very large transexual woman grotesquely playing a flirtatious role usually inhabited by someone petite and cute. At the performance I saw, this production was far too “woke” for most of the audience to tolerate.

Which brings me to the Hollywood version from 1955. After seeing Woke-lahoma! on the Ahmanson stage, I was glad to turn to a more traditional version, with the appealing Gordon MacRae as Curly, the lovely Shirley Jones making her film debut as Laurey, and other Hollywood musical stalwarts in the cast. The de Mille ballet remains excessive, featuring the dream-Laurey psychologically shaken by seeing a leering Jud in the company of some racy painted ladies. And some new histrionics are added, like Laurie pushing Jud out of his wagon when he tries to kiss her, and then Jud viciously setting fire to a haystack in an act of revenge. In this film, Jud is played by Rod Steiger. I hear Marlon Brando was considered for the role, and his brooding handsomeness might have helped explain the attraction/repulsion Laurey is supposed to be feeling. But who’d be tempted to go astray with as stolid a guy as Steiger? This casting just confirms the show’s basic contradictions. Rodgers and Hammerstein would try again to balance romantic fun with sexual tension in their next show, the brilliant Carousel.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers