Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 32

September 27, 2022

Howard Hughes, Melvin Dummar, and the American (Dollar) Dream

Jonathan Demme’s Melvin and Howard is a small movie about small people, unless you count reclusive zillionaire Howard Hughes, whose massive shadow hangs over the whole enterprise. Dennis Bingham's Whose Lives Are They Anyway? The Biopic as Contemporary Film Genrecites Melvin and Howard as the first film in the subgenre "biopic of someone undeserving.” The undeserving someone in this case is Melvin Dummar, the Utah man who, after Hughes’ death in 1976, popped up as a major beneficiary of Hughes’ vast estate by way of a mysterious handwritten will unearthed at the headquarters of the Mormon Church in Salt Lake City. The so-called Mormon Will was eventually judged a blatant forgery. But through a number of court hearings Dummar continued to insist that he’d rescued Hughes in the Nevada desert in 1967, giving a needy old man a friendly lift to Las Vegas.

Melvin and Howard is a fanciful riff on that slice of history, taking Dummar’s story at face value. (Hollywood veteran Bo Goldman won an original screenplay Oscar for his lively telling of the tale.) It begins with a scruffy and maniacal Howard Hughes (played with his usual panache by Jason Robards) gleefully racing his chopper through the desert, before the fun ends with a spectacular crash. Hours later, garage mechanic Dummar happens along in his truck, stops to take a leak, and discovers the fallen tycoon. Throughout their ride, Hughes remains taciturn and cranky, until the chatty Dummar gets him to singing a favorite old song, “Bye Bye, Blackbird.” At journey’s end, after Hughes reveals his identity (and borrows some cash), they go their separate ways.

The bulk of the film is a portrait of Dummar (well played by Paul Le Mat) as a perennial dreamer, someone who can’t hold down a job but is convinced that happy days are just around the corner. He loves wife Lynda (the adorably ditsy Mary Steenburgen in her Oscar-winning role), but can’t quite seem to provide a stable life. The centerpiece of the film is the on-again off-again marriage of these two: at one point she leaves him and their daughter to work in a topless bar. Their fortunes seem to turn when he gets Lynda onto a talent-and-game show in which (despite her tap-dancing ineptitude) she wins a large sum of money, all of which Melvin quickly squanders. The romantic allure of money, as seen in this segment, is at this film’s very heart. The show is called Easy Street, and its smarmy host alternates between sexual innuendo and a worshipful attitude toward big bucks. It seems all too apt that Lynda’s tap routine is performed to the Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction.”

If you’re Melvin Dummar—a laid-back guy convinced that life on Easy Street awaits if only you believe hard enough—it’s perfectly likely that Howard Hughes would leave you a fortune. The question of the mysterious will continued to dog the real Dummar’s life, which ended in 2018. Melvin and Howard, though, concludes long before that, returning to the footage of two unlikely buddies, an old man and a young one, joyfully belting out an old musical-hall tune.

I worked briefly with Jonathan Demme in 1974, when he’d just returned from directing his first film, Caged Heat, for Roger Corman’s New World Pictures. He moved on to some studio gigs, but Melvin and Howard was his true breakthrough, showing off his skill at capturing American life and moving him toward the big pictures, like 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs. (I’ll mention in passing his sharp ear for musical scoring.) Unfortunately he left us much too soon.

September 23, 2022

Two Who Only Live Once

No, You Only Live Once is not one-half of a James Bond movie. (Sorry about that!) Instead it’s an early film noir, dating back to 1937, about an ill-fated couple who hit the road after the husband’s violent escape from prison. There’s a long tradition in Hollywood of movies that focus on lovers who share a passion for fast cars and lives of crime. When I was coming into my own as a film enthusiast, the unforgettable flick was Bonnie and Clyde, which used the story of two actual Depression-era bank robbers to celebrate the audacity and the undying love of a doomed pair. Admirers of Bonnie and Clyde tend to think back to films like 1950’s Gun Crazy for a similarly enticing blend of love, sex, and violence.

But earlier “lovers on the lam” movies, like 1948’s They Live By Night, treat crime sprees with less exuberance. Their emphasis is on social wrongs that trap basically good-hearted lovers in nightmarish situations from which violence seems the only escape. I was interested to see this hold true in You Only Live Once, the second Hollywood film of the great Austrian director Fritz Lang., whose early credits included Expressionist masterpieces like Metropolis and M. Top-billed in You Only Live Once is Sylvia Sidney, a long-lived star who would be nominated for an Oscar more than thirty years later, as Best Supporting Actress for Summer Wishes, Winter Dreams. In You Only Live Once, she’s Joan, an efficient, ebullient career gal, working for a local public defender who adores her. To his dismay, she’s head-over-heels about a young convict, who’s just won release after his third prison stint. As played by rising star Henry Fonda, Eddie is an earnest young man who’s survived a rough upbringing. Ashamed of his past misdeeds, he’s determined to marry Joan and embark on a life of sober domestic bliss.

After a joyous homecoming, Eddie’s problems continue to mount. Though he’s been promised a steady job as a truckdriver, his unsympathetic boss finds an easy excuse to fire him. A search for another position turns futile: no one wants to trust a guy with a prison record, no matter how much he’s determined to keep to the straight and narrow. (It’s the Depression, of course, so all jobs are scarce, but the film also seems to condemn a system that offers no constructive support to those who’ve left prison walls behind.)

For Eddie, desperate to support himself and his wife, a return to crime seems to be the only alternative. But when a local bank robbery results in several deaths he swears he had nothing to do with it. No matter: he’s tried and convicted, ending up on Death Row.

While loyal Joan struggles to free him, his execution date nears. A last-minute exoneration by the governor ironically results in more tragedy, including the death of one of Eddie’s most selfless supporters. Soon he and Joan are fleeing into the hinterlands, living as best they can. (Somewhere in there, Joan has a baby, without ever seeming to have been pregnant or in labor: the Thirties was a great decade for sweeping physical reality under the rug.)

You Only Live Once isn’t raw and exciting, like such later lovers-on-the-lam films as Badlands and Thieves Like Us. Instead it’s heart-wrenchingly sad, with the intense Fonda and the vivacious Sidney suggesting to the viewer how human potential is wasted when basically good people are trapped by circumstances beyond their control. All they want is to live and love . . . but you only live once.

September 20, 2022

The Lincoln (Theatre) Log

A hundred years ago, when movie houses were a brand-new phenomenon, many of them became the centerpieces of their communities, places where locals could gather to laugh and cry over what they saw on screen. Via the hard work of the L.A. Conservancy, Los Angeles has managed to preserve some of its onetime movie palaces, particularly on Downtown’s Broadway. The Conservancy’s “Last Remaining Seats” film series, featuring movie classics and related stage presentations, has been around for 35 years. Happily, it has returned, following 2 years of pandemic closures, allowing Angelenos to watch old favorites in such pristine (and hugely historic) venues as the Orpheum, the Los Angeles Theatre, and the elegant United Artists. I was last at the Orpheum, home of a mighty Wurlitzer organ, several years ago, introducing an excited seven-year-old to Laurel and Hardy (and the pie fight to end all pie fights). It was one of my favorite afternoons of all time.

Small towns may not have had the wherewithal to support gargantuan movie palaces, complete with elegant lounges and “crying rooms” for babies and their mothers. Still, many towns had their own movie houses, which quickly became the center of local lives. A lot of these are gone now, having fallen victim to real estate booms and urban decay. In some cases, the old marquees (and quaint glassed-in ticket booths) survive, but not the theatres themselves. But I’m always cheered when I come across a classic movie house from the 1920s, one that still fulfills a need within its community.

I found one such recently in Mount Vernon, Washington, a cozy town at the heart of Skagit County, not far outside of Seattle. This amiable community features on its main street a cooperative health-food market, some artists’ ateliers, artisanal coffee places (of course!), and boutiques. But I was drawn to the Lincoln Theatre, dating back to 1926, and thriving now as the county’s historic performing and cinematic arts center.

The Lincoln Theatre began life as a vaudeville house that also screened silent movies. (Yes, it too boasts a Wurlitzer organ.) For years it featured first-run films, but in 1987 a community foundation purchased the place and began using it for local events. The shutdown of the pandemic years allowed for a throughgoing refurbishing, designed to return the Lincoln to its original glory. Now it hosts—in addition to movies—local youth theatre performances, touring musicians, live-opera screenings from the MET, a Voices of the Children festival, and other well-attended gatherings. (And, yes, also the Skagit Drag Show, scheduled to take place not long before Halloween.) On the afternoon I was there, a local volunteer proudly showed me around, while her colleagues bustled to prepare for that evening’s Spoken Word presentation, It was to feature Washington State poet laureate Rena Priest, an Indigenous woman with strong environmental interests. Everyone seemed excited about the audience participation aspect of Priest’s appearance, which would encourage the audience to join in by making their own salmon-related poems.

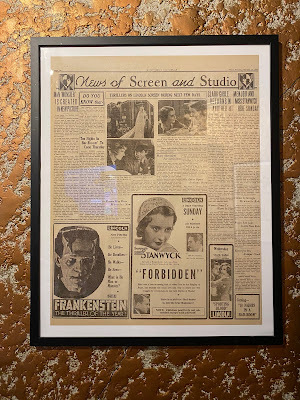

The lobby of the Lincoln has been expanded to include the inevitable wine and coffee bar, but you can also go old-school, munching on freshly-made popcorn. Gazing around at the framed copies of “News of Screen and Studio,” I saw big ads for Boris Karloff in Frankenstein and Barbara Stanwyck in Forbidden at the Lincoln. Today’s presentations aren’t quite so splashy, I suspect, but the Lincoln continues to fulfill its role in both amusing and enlightening audiences who come all the way from Seattle and Vancouver for good hometown entertainment. And you can’t ask for much more than that.

The lobby of the Lincoln has been expanded to include the inevitable wine and coffee bar, but you can also go old-school, munching on freshly-made popcorn. Gazing around at the framed copies of “News of Screen and Studio,” I saw big ads for Boris Karloff in Frankenstein and Barbara Stanwyck in Forbidden at the Lincoln. Today’s presentations aren’t quite so splashy, I suspect, but the Lincoln continues to fulfill its role in both amusing and enlightening audiences who come all the way from Seattle and Vancouver for good hometown entertainment. And you can’t ask for much more than that.

September 16, 2022

A Salute to Three We’ve Lost: Jean-Luc Godard, Marsha Hunt, Irene Papas

Original French poster for "Breathless"

Original French poster for "Breathless"I can’t pretend to be an enormous fan of Jean-Luc Godard, the French/Swiss cinephile whose movies shook up the status quo of the filmmaking world for a remarkable 60 years. Godard (who died September 13) made films I found far more provocative than enjoyable. But he always had something interesting on his mind, and he was certainly terrific with quips about the nature of cinema. Godard, who like most French filmmakers coming out of the Sixties began as a critic, certainly knew how to boil the film medium down to its essence. One of his most familiar aphorisms could also be the motto of my former boss, Roger Corman: “All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun.”

Godard’s appreciation for classic genre films (like American film noir and “lovers on the lam” flicks) led him to make his own hardboiled crime dramas. These obviously include the one that kickstarted his career, 1960’s Breathless, starring Jean-Paul Belmondo as a petty Paris crook and Jean Seberg as the girl who betrays him. Through my own research on the great American films of the late Sixties, I was surprised to discover the intimate connection between Godard’s sort of deliberately ironic filmmaking and 1967’s indelible Bonnie and Clyde.The unheralded young writers of that script, Robert Benton and Thomas Newman, were such fans of the French New Wave that they watched films like Breathless and François Truffaut’s Jules and Jim multiple times and sought to make their own hero, Clyde Barrow, a cool gangster-type in the Belmondo mold.

When Benton and Newman managed to meet Truffaut in New York City to discuss their project, he showed his passion for low-rent American crime drama by screening for them 1950’s Gun Crazy, a sleek and moody black & white road pic starring Peggy Cummins and John Dall. But despite his enthusiasm for Bonnie and Clyde, Truffaut was already committed to filming Fahrenheit 451, his only English-language film. (Big mistake, in my opinion!) That’s why he turned the script over to his pal Godard, who seriously considered it. As I recollect, Godard aimed to move quickly, paying little mind to the Texas locale and the period authenticity of Clyde and Bonnie’s historic crime spree, so I’m relieved that the material finally came into the hands of Arthur Penn, a meticulous craftsman who made it his masterpiece. Still, Godard didn’t give up on his fascination with gangsters, treating them with fierce and funny irony in Pierrot le Fou.

We’ve seen two other important movieland deaths in the last week or so. Marsha Hunt, a rising actress whose career was derailed by the Red Scare of the 1950s, lived to be 104. Though a mention in Red Channels stopped her career momentum forever, she never lost her courageous commitment to causes in which she believed. I met her about ten years ago at a do-good event related to climate change. Appropriately, she was treated as a most honored guest.

I was especially saddened to read about the passing of the lovely and soulful Greek actress, Irene Papas. In the era when I was discovering foreign-language cinema, her appearances in films based on the classical Greek tragedies were not to be missed. Yes, she also made Hollywood movies like The Guns of Navarrone, but I will always think of her in the title roles of Antigone and Electra. In the latter film, she was directed by the great Michael Cacoyannis, who used her cinematic firepower again later in The Trojan Women and Iphigenia. . . and of course in Zorba the Greek.

September 13, 2022

Attack of the Monster Musical: “Little Shop of Horrors” Sings!

In the beginning, there was (isn’t there always?) Roger Corman, who bet he could shoot a movie over a weekend, using sets left over from another production. The idea for a man-eating plant came from the warped brain of Charles B. Griffith, who cranked out the screenplay, helped with night-shooting at scruffy Downtown L.A. locations, and personally voiced Audrey Junior’s imperious demand that the hero “Feed Me!” Chuck’s partner in cinema crime was another Corman regular, portly Mel Welles, who was also featured on-screen as flower-shop owner Gravis Mushnik. Together the two pals scoured L.A.’s real Skid Row for cheap outdoor locations that could be rented for the price of a bottle of scotch. Others in the cast included Jonathan Haze as the nebbishy Seymour Krelboined, Jackie Joseph as the naïve and lovable Audrey, and a then-unknown Jack Nicholson as an excited masochist in a dentist’s chair. (“No Novocain—it dulls the senses.”)

In the beginning, there was (isn’t there always?) Roger Corman, who bet he could shoot a movie over a weekend, using sets left over from another production. The idea for a man-eating plant came from the warped brain of Charles B. Griffith, who cranked out the screenplay, helped with night-shooting at scruffy Downtown L.A. locations, and personally voiced Audrey Junior’s imperious demand that the hero “Feed Me!” Chuck’s partner in cinema crime was another Corman regular, portly Mel Welles, who was also featured on-screen as flower-shop owner Gravis Mushnik. Together the two pals scoured L.A.’s real Skid Row for cheap outdoor locations that could be rented for the price of a bottle of scotch. Others in the cast included Jonathan Haze as the nebbishy Seymour Krelboined, Jackie Joseph as the naïve and lovable Audrey, and a then-unknown Jack Nicholson as an excited masochist in a dentist’s chair. (“No Novocain—it dulls the senses.”) All this happened in 1960, producing a horror comedy that was not exactly Oscar bait. Still, over the decades it accrued a loyal fan base, mostly comprised of young people who fell in love with this black & white cheapie on the Late Late Show. One of these people was Howard Ashman, who would grow up to be an off-off-Broadway director and lyricist. A collaboration with budding composer Alan Menken led to a 1982 workshop production that turned into a five-year run at Off- Broadway’s Orpheum Theatre. This was an East Village locale so shabby that it made a perfect fit for a darkly comedic Skid Row saga.

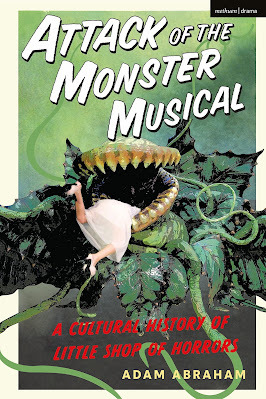

There’ve long been books dedicated to the 1960 Corman film. But in Attack of the Monster Musical, pop culture historian Adam Abraham devotes himself specifically to the musical version and how it grew. I met Adam on the telephone when he quizzed me, as a Corman chronicler, about the source material. Thanks to my research on Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers, I was able to connect him with such Cormanites as Steve Barnett, who (following the runaway success of the musical), tracked down the missing elements that allowed Roger—at long last—to copyright a film that had been in public domain since its first release,. But Adam has clearly talked to EVERYONE who’s had anything to do with various productions of Little Shop: the actors, the understudies, the orchestrators, the stage managers, the Hollywood moguls who put together the 1986 film version. Abraham’s book is the essential source if you want to understand how the original 72-minute film evolved into a cut-rate extravaganza featuring man-eating muppets and a lively score based on doo-wop and early Motown. After reading his book, it’s easy to appreciate how successfully the creaky Corman opus was transformed, thanks to the addition of a sadistic dentist, a trio of Skid Row Supremes, and a jive-talking Audrey II.

Theatre buff that he is, Abraham is shrewd about locating Little Shop among other low-rent Off-Broadway musicals (like Dames at Sea) that capture the spirit of the films of yesteryear. He also contemplates the appeal to Hollywood of the Ashman-Menken opus, at a time when Revenge of the Nerds was big box-office. But he’s quick to point out how the grandiose $25 million film directed by Frank Oz undermines the charm of the original stage production, relying on star cameos (like Bill Murray in the extraneous Jack Nicholson role) and never really growing into something special. From what I hear, Hollywood’s planning to try again, with (perhaps) Billy Porter as the voice of Audrey II. Maybe this time the plant will flower.

Use musical film poster + Adam’s book cover

September 9, 2022

Looking Back in Admiration . . . or Anger

Yesterday the airwaves were full of the news that Queen Elizabeth II, Britain’s reigning monarch for a remarkable seventy years, had passed away at 96. Though the British monarchy certainly has its detractors, the loss of a woman marked by dignity and a strong sense of obligation to the commonweal was regarded by most of the world as a poignant moment. Looking back on her ascension to the throne as a 25-year-old in 1952, I realize that her reign coincided almost exactly with something brand-new on the British stage: the Angry Young Man.

It all started with a 1956 play by John Osborne, one that ushered in plays, films, and fiction marked by a furious disdain for the status quo. Alan Sillitoe, who was to write such lacerating works as The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, said of Osborne that he "didn't contribute to British theatre, he set off a landmine and blew most of it up." Osborne’s semi-autobiographical Look Back in Anger, disdained by most critics but hailed by a prescient few as the shape of things to come, focuses in on the crumbling marriage of a young working-class man, Jimmy Porter, and his more pedigreed wife, Alison. Jimmy has managed to get an education, but resents everything about the world of his betters. Much of the play (set in a squalid Midland flat) features his sometimes comic, sometimes cruel diatribes against his wife, his sweet-natured buddy, the social status quo, and everything else that crosses his path. The film version, released in 1959, featured rising star Richard Burton, along with Claire Bloom and an expanded cast of characters. It garnered an X rating from the British censors, and—though nominated for a few British awards—made absolutely no dent on Hollywood.

I hadn’t realized that the play was filmed again, for television, in 1989. It was helmed by Judi Dench, in her only directorial outing, and its stars included a then-married couple who were starting to make their own impact on theatre and film. In that same year, Branagh had both shot and starred in his stirring rendition of Shakespeare’s Henry V, scooping up his first two Oscar nominations (he won in 2022 for his Belfast screenplay). Thompson, newer to the big screen, would go on to win Oscars for acting (Howards End) and screenwriting (Sense and Sensibility). The Branagh/Thompson marriage, which led to several creative collaborations on stage and screen, ended in 1995, apparently because Branagh had moved on to Helena Bonham-Carter, in a dynamic that had some parallels to Look Back in Anger. But what struck me was that both Branagh (born in 1960) and Thompson (1959) started their lives at a time when Look Back in Anger was galvanizing the art world.

As Jimmy Porter, Branagh has the real goods. He’s funny; he’s angry; he’s constantly in motion. This production, which began on the British stage, is completely faithful to Osborne’s tiny cast and one-set location. There’s no room for fancy camera work, and everything depends on Branagh firmly holding our attention as he goes off onto his endless rants. And so he does. I’d like to say that his working-class roots, as seen in the autobiographical Belfast, make his a Jimmy Porter we believe through and through.

Thompson, as the woebegone Alison, has the harder job, tamping down her vibrant personality to persuade us that she’s willing to remain Jimmy’s doormat. But the toughest role belongs to Helena Charles (Siobhan Redmond), the posh friend of Alison’s who shows up at midpoint and makes some bewildering choices. Still, this remains a mesmerizing production.

September 6, 2022

Suffering Little Children

Little Children (2006) is the only film I can think of in which a pedophile is probably the most sympathetic adult character. Tom Perotta, who adapted his popular novel for the screen along with director Todd Field, is less concerned with the danger presented to children by the psychologically warped Ronnie McGorvey (an Oscar-nominated performance by Jackie Earle Haley) than by the self-absorbed parents who follow their own bliss in this whitebread suburban town. The film’s ending, from what I gather, is a major departure from Perotta’s novel, in which Ronnie’s obsession with kids leads to a very different, though equally disturbing, climax.

I’ve also heard that this is the rare film that is superior to its source material. I can’t speak to that, but I can see how Perotta’s novel about seven lost souls has been shaped and sharpened in order to zero in on a few really key relationships. The most vivid is that of Sarah (a rather bedraggled Kate Winslet) and Brad (a squeaky-clean Patrick Wilson). Sarah’s a desperate housewife and former self-proclaimed radical feminist who takes pride in keeping her distance from the other young moms in the local playground set. It doesn’t help that her husband, an older man who’s been married before, turns out to have an obsession with Internet porn. (A very tongue-in-cheek narrator shows us the outrageous moment when Sarah catches her spouse in flagrante with the on-screen Slutty Kay.)

Brad (nicknamed “the Prom King” by the playground moms) is restless in his role as househusband and aspiring lawyer, married to an ambitious maker of documentary films. He’s happy enough pushing his little son on the swing-set, but only pretends to be studying for the upcoming bar exam. What he really seems to covet is physical thrills, of the sort he once felt as a college quarterback. Brad’s and Sarah’s spouses are far more deeply explored in Perotta’s novel, but on film the spotlight shines bright on the couple’s passionate extramarital affair, sparked by time spent together at the community swimming pool, and then consummated as their four-year-olds nap in another room.

Played off against this wild and crazy coupling is the story of Ronnie McGorvey, newly released from prison following an episode in which he exposed himself to a local child. Now living in the neighborhood with his supportive, though slightly addled, mother, he wants only to be left in peace. But a self-righteous ex-cop leads the charge to hound Ronnie from town, even coming to his door late at night to harass him via loudspeaker, making sure Ronnie knows that he’s the neighborhood pariah and always will be.

Of course no good can come of all this. It’s an unusual hallmark of this film that we understand the pain and frustration of the local residents at the same time that the narrator’s comic detachment moves the story along. I can only assume that the witty tone of the narrative comes direct from Perotta’s novel. It’s startling, at first, to hear so much detached narration setting the stage for the story we’re about to watch. It reminded me of a far different film with far different goals, Tony Richardson’s filmic adaptation of Fielding’s 18th century comic gem, Tom Jones. Later on, as this wry voice faded away, I began to miss it. But of course detached wit, going on at length, would overly divert us from the fundamentally serious tale we see unfolding on screen. Though modern life has its darkly comic side (Starbucks barristas! Online shopping sprees! Internet smut!), there’s nothing funny about the destruction of marriages and families.

September 2, 2022

The Story of “The Nun’s Story”

Little girls of my generation were fascinated by nuns. This had nothing to do with being Roman Catholic: in my recollection the kids with the least respect for nuns were those unfortunates who attended Catholic schools, and were subjected to what they saw as a rigid and humorless group. But those of us with zero Catholic connection were entranced by the long heavy robes, the cropped heads covered by veils, the very idea that someone would wholly give up her private life for the sake of an ancient ritual. That’s probably why we gravitated toward everything from Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison to The Sound of Music. And, of course, we read Katherine Hulme’s 1956 best-seller, The Nun’s Story, based on the life of an actual Belgian nun who nursed the sick in the Congo during World War II. Somehow, though, I never saw the major Hollywood film based on that novel—until now.

It's well known (everywhere but at the new Academy Museum) that the American film industry was largely started by Jewish immigrants. Still, despite the ethnic backgrounds of men like Jack Warner, Carl Laemmle, and Samuel Goldwyn, they were eager to please the American public by hewing as closely as possible to what they viewed as traditional American values. From the moment that censorship threatened to enter the picture, studio bosses actively looked to the Catholic Church for public approval of their projects. Particularly in the 1930s, the point-person within the industry who was charged with keeping the silver screen moral was Joseph Ignatius Breen, a devout Roman Catholic. Breen, who enforced the so-called Hays Code with missionary zeal, made sure that Hollywood films did not stray from subjects and behaviors of which the Church approved. Even after Breen’s retirement, the infamous Production Code continued to be largely enforced, until the arrival of television made the industry eager to capture and hold new audiences—at which point (we’re talking about the Sixties, of course) all hell broke loose.

What I hadn’t realized until now was that a big-budget film based on Hulme’s popular novel was hardly a slam dunk. Apparently, Warner Bros. sought to bring this material to the screen before the book was even published, but naysayers worried that its story—which depicts a gifted young woman’s inability to make peace with the unrelenting demands of her order—might alienate Catholics by casting a dim light on Church values. After all, Sister Luke must agree to suppress her vibrant personality in order to conform to Church requirements for obedience. At one point she’s even told by a superior to fail an all-important exam as a necessary exercise in humility. Eventually director Fred Zinnemann and screenwriter Robert Anderson (neither of them Catholic) were persuaded that it was essential not to criticize the Sisters of Charity of Jesus and Mary, while also acknowledging that Sister Luke, for all her talents, was unsuited to the strict discipline the order required.

Without Audrey Hepburn in the starring role, there would apparently have been no film. She’s perfectly cast as a young woman in love with God and with the chance to save souls by repairing damaged bodies. In the film’s early scenes, we are steeped in Church ritual—the flickering candles, the solemn processions, the rapt faces—and understand her commitment. But we also see how she blossoms, far from the Mother Church, in the Belgian Congo, where she can put her intelligence to work, unafraid of violating arcane rules of modesty and silence. In the year of Ben-Hur, this film garnered 8 Oscar nominations, but (alas) not a single win.

Happy birthday to Hilary, who (thankfully) is not a nun.

August 30, 2022

Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris; Mr. Gernreich Did Not

I’ve been spending a lot of time lately researching a Sixties fashion guru, Rudi Gernreich, for a writing project. The experience has made me realize how much fashion shapes our everyday lives, especially if we happen to be female. Gernreich, notorious circa 1964 for daring to create a topless bathing suit, was in many ways a fashion radical. Though he was an award-winning designer with a celebrity clientele, he eventually came around to asserting that “fashion will go out of fashion,” and that individual freedom and comfort are far more important than high style.

Gernreich, who would have turned 100 this month (he died in 1985), gradually became a champion of low-key, easy-care, and often unisex garments. Not for him the glamour and expensive individualism of the great Paris couturiers, whose business model was to create sumptuous styles intimately tailored to fit each client’s body. So he makes an interesting contrast to the story of Mrs. Ada Harris (based on a popular 1958 novel by Paul Gallico), a London charwoman who has a hard time making ends meet. It’s 1957, and she still doesn’t know for sure that her beloved husband died in World War II. A romantic at heart, she unexpectedly falls in love with a fabulous Dior gown all-too-casually worn by one of her wealthy clients. When a small windfall comes her way, she makes up her mind to cross the channel and purchase an extravagant gown of her very own.

When she enters the House of Dior, she’s immediately hit by the snobbery inherent in the world of couture. Dior’s clients are expected to be the wealthy, the titled, and the celebrated: snooty folks who treat Dior underlings with disdain and often don’t bother to pay their bills. Through a series of happy accidents and just plain chutzpah, Mrs. Harris wins acceptance among the models and dressmakers. As played by the very talented Lesley Manville, she possesses spirit and good sense, both of which endear her to the working-class peons who make the extravagant garments. Soon she’s finding common-sense ways to help the House of Dior with its fiscal problems, and we just know that she and her new gown will (after a few challenges are overcome) live happily ever after.

I first became truly aware of Lesley Manville in 2017, when she copped an Oscar nomination for playing the steely sister of Daniel Day-Lewis in Phantom Thread. That film too was set in the haute-couture fashion world, with Day-Lewis starring as an imperious designer named Reynolds Woodcock. Clearly, in Phantom Thread, both Woodcocks are far more dedicated to clothing than they are to people. (A highlight is the moment when the two siblings conspire to strip an elegant green dress off of the drunken body of a wealthy patroness who in their eyes just doesn’t deserve the masterpiece she’s wearing.) In Phantom Thread, Manville was essentially frigid, so it’s a pleasure to see her turn on the charm. Like so many British actors, she seems able to do just about anything.

While watching Manville in Phantom Thread, I suddenly recognized her as the loyal but deeply frustrated wife of Sir Arthur Gilbert (Jim Broadbent), in Mike Leigh’s wonderful Gilbert & Sullivan film, Topsy-Turvy, I also was lucky enough to see her on-stage opposite Jeremy Irons, doing remarkable things with the role of the drug-addled Mary Tyrone in Eugene O’Neill’s classic Long Day’s Journey into Night. And it’s no surprise that she’ll soon pop up in the latest season of The Crown, playing the ageing (and deeply troubled) Princess Margaret. Personally, I can’t wait.

August 26, 2022

A Short Stay at “The White Lotus”

The pandemic has taught me that there’s something to be said for committing to a limited TV series. Over the course of a relatively small number of hour-long episodes, you can get absorbed in a complicated story, featuring many provocative characters, and assume that you’re heading for a quick but engrossing wrap-up (or, of course, a dramatic cliff-hanger that makes you eager to see what the next season will bring).

For the last six nights, I have been caught up in The White Lotus, I know this HBO series, set in a tropical resort frequented by the rich and the entitled, has been around for months, but I’m a bit slow to explore TV trends. Lots of buzz and 20 primetime Emmy nominations (eight of them in acting categories) made me curious, and so I hopped aboard for a series of episodes that balance the life-crises of a number of wealthy vacationers and the woes of the ever-smiling folk who serve them. If you enjoy the overblown Jennifer Coolidge, she’s very much here, larger than life, as an addled heiress who feels the need to scatter her dead mother’s ashes in the surf. There’s also a newlywed couple discovering that perhaps they weren’t meant for each other (the groom’s imperious mother, played by Molly Shannon, pops up to check on things). And there’s a complicated story involving a business-tycoon mom, an insecure dad, a confused son, a rebellious college-age daughter, and the daughter’s mixed-race pal whose complex social resentments lead toward a tragedy for a young busboy but also a burst of family feelings that had previously seemed most unlikely.

Then there’s the White Lotus staff, as represented by two of the show’s most memorable characters. Natasha Rothwell (one of the show’s many acting nominees) is the resort’s wellness coordinator, a soothing presence not quite resigned to the fact that she’s taken for granted by one and all. And it will be hard for me (or anyone else, I should think) to forget Murray Bartlett as the resort’s manager. He starts out as a glad-hander determined to make all the guests feel the joys of Hawaiian hospitality, while simultaneously fighting for his own recovery from addiction. Yes, he’s five years clean and sober, but the shenanigans of this particular set of guests erase all of that hard work in one fell swoop. When he goes off the wagon, his is a spectacular plummet. Let’s just say that the revenge he ultimately takes on his most obnoxious guest is both disgusting and hilarious.

What makes it all work is an opening scene in the first episode, set at the local airport after the events the series recounts, which establishes that there’s just been a death at the White Lotus resort. The scene contains a strong hint of the victim’s identity, and so we go through each episode waiting for the axe to fall. In fact, the writers have indulged in a bit of misdirection here, as a way of ratcheting up suspense and keeping us invested in all the goings-on the series contains. This proved effective for me, at the same time that I was irked by some serious flaws in plot logic and a too-tidy sign-off.

The word is that we have not seen the last of The White Lotus, although that beautiful Hawaiian resort (played by an actual resort on Maui) will be replaced in the new season by an equally fabulous locale in Sicily. It will feature an international cast, the return of Jennifer Coolidge, and (doubtless) some additional icky delights.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers