Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 45

July 1, 2021

Where’s The Baby?: The Mysterious Vanishing Child in “Call My Agent” and “Breaking Bad”

I’ve just finished watching the last episodes of Call My Agent!, the French dramedy about love and loss at a Parisian talent agency. The final season settled the future of the ASK agency, while also wrapping up the fate of passionate Andréa, scheming Matthias, idealistic Gabriél, and eager young Camille. While these and other major characters strutted and fretted (and while real-life French celebrities enjoyed poking fun at their own foibles), I came to appreciate how much of the last episodes was focused on a very basic human concern, at least among women: basic childcare.

When one of the series’ major characters very unexpectedly finds herself with child, she goes through with the pregnancy partly because she’s got a supportive romantic partner who longs to be a parent. Though she vows to be a fully engaged maman to baby Flora, her hectic schedule as an agent tasked with solving the sometimes childish problems of major movie stars keeps her hopping 24/7. Always at her clients’ beck and call, she often leaves her partner in the lurch, despite promising to do her share of nurturing Flora and participating in a trendy but rigorous cooperative daycare venture. Ultimately, at midseason, her insistence on putting work before family drives her partner away, leaving her in sole charge of her tiny daughter.

So much of the last season is spent with this character trundling her baby around Paris, packing her away in the agency’s conference room, and deviously leaving her at the daycare center unsupervised, until the wee hours. (This is, of course, the world’s most cooperative little girl, one who takes all these shifts in stride and rarely cries from hunger or frustration.) There’s even one moment when the hard-working agent needs to show up around midnight to see Sigourney Weaver hosting a bacchanale at the famous Père Lachaise Cemetery (don’t ask!). At that point, I loudly asked my TV set, “Where’s the baby?”

Mostly, though, I respect this series for recognizing that childcare is necessary, and that babies (however cute and cooperative) can’t conveniently disappear from their parents’ lives when the storyline doesn’t make room for their presence. In the series’ final episode, the question of childcare comes to the fore, leaving the mother forced to make an important life-choice.

By way of contrast, I’m currently working my way through the five seasons of the AMC classic series, Breaking Bad. I don’t know how it all comes out in the end, but I do know that, for all its brilliance, Breaking Bad does prompt me to frequently shout at my screen, “Where’s the baby?”

At the very beginning of Breaking Bad, the loving wife of Walter White is hugely pregnant. While Walt evolves from mild-mannered high school chemistry teacher to drug lord, wife Skyler dramatically bears the child, contends with her husband’s cancer diagnosis, discovers his new secret career as a meth producer, and then embarks on a career shift of her own. Yes, baby Holly occasionally pops up, to be cuddled by one of the characters and then plopped into a carseat, but she also disappears for episodes at a time, while her baby-free parents take care of business without explanation. Daycare providers are probably involved somehow, but the story never makes room to even mention their role in this dramatically evolving household.

Which is not to imply that I’m not enjoying Breaking Bad. It’s a brilliantly suspenseful series, chock full of unexpected moments. But as a mother myself I know that bringing up baby is definitely a full-time occupation—for someone. Why can’t more dramas bear this in mind?

June 28, 2021

A Human Being Prepares: Learning the Kominsky Method

I’m sad to see the demise of The Kominsky Method, the limited comedy series created by TV veteran Chuck Lorre and starring a top-of-his-game Michael Douglas. The series ran for three years on Netflix: thanks to streaming, I’ve just now watched the final episode, which left the core characters, as usual, both happy and sad. I use the word “demise” intentionally, because The Kominsky Method—though ostensibly about making it in Hollywood—has a lot to say about death. Chuck Lorre, whose past credentials include such mega-hits as Two and a Half Men and The Big Bang Theory, is now approaching 70. Michael Douglas is 76. Both of them know, I assume, about the bodily frailties and psychological embarrassments that come with the territory. That’s why the show jokes wryly about prostate problems and other indignities connected with an ageing body, at the same time that the central character is still as ambitious, as horny, and occasionally as childish as ever.

In its opening episode, The Kominsky Method starts with a death. The last season starts with a death too, one that fans were hardly expecting, but one that leads into perhaps the most subtly hilarious funeral of all time. The handling of the death of a loved one is high among the series’ great themes. All too aware of his own mortality, Douglas’s character strives to do the right thing. Others, though, seem to see the loss of a close relative as an opportunity: in the last season, Haley Joel Osment (no longer the boy who once saw dead people) views the passing of a family elder as a chance to line his own pockets while burnishing his credentials as a Scientology initiate. Then there’s Kominsky’s former wife, played by the always-welcome Kathleen Turner, who has acted opposite Douglas in several terrific films. She helps embody the motif of reconciliation that Lorre has said (see below) is the great thrust of the final season. As both a medical doctor and a patient she has her own complex relationship to matters of mortality, as well as a salty tongue that will not allow Death to be proud.

But The Kominsky Method is also fundamentally about Hollywood: its egos, its traditions, its winners and losers. The Douglas character, Sandy Kominsky, is an actor who—having belly-flopped in Hollywood—remakes himself as a teacher of acting. Anyone who’s ever taken a drama class knows what the typical acting guru is like: someone who pontificates at length, implying that he (or she) would have been a great star if not for the indignities of the system. In seasons 1 or 2, some of my favorite moments have come from the eager acolytes who hang onto Kominsky’s every work, sometimes taking his advice to ludicrous extremes. Like – when he urges students to be bold in their acting choices – a young white woman decides to emulate Marlon Brando in A Streetcar Named Desire or take on a Black male role. Naturally, in a series with this sort of pedigree, there are guest appearances by some genuine Hollywood stars. No less than Allison Janney and Morgan Freeman stop by the Kominsky studio. Janney tartly undercuts Sandy’s basic acting philosophy, while Freeman seems most intent on selling his own on-line services as an acting coach. For those who are part of what Hollywood lovingly calls “the industry,” the in-jokes are priceless.

I wouldn’t dream of closing without mentioning the octogenarian Alan Arkin, who graces the first two seasons in his role as Kominsky’s agent and best friend. Arkin and Douglas together are comedy gold.

June 24, 2021

At Wits’ End: The Poignant Brilliance of “Wit”

The 1995 play called Wit, written by a teacher who’d once worked in a research hospital, was a triumph for South Coast Repertory, the premiere theatre in SoCal’s Orange County. When Margaret Edson, who had never written a play, sent her script to 60 of America’s regional theatre companies, most turned it down flat. But South Coast Rep saw in this story of a lauded college professor facing aggressive experimental treatment for ovarian cancer a promising stage vehicle. SCR’s production went on to win major awards from the Los Angeles theatre community, after which the play moved east to New Haven and New York. There it swept up additional honors, including the 1999 Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

The intimacy of Wit’s drama, along with the bleakness of its subject matter, meant that Hollywood didn’t rush to snap up the film rights. But in 2001 HBO put its clout behind a TV movie, securing the services of Mike Nichols as director (two years before his triumphant TV staging of Angels in America), and Emma Thompson in the central role of Professor Vivian Bearing, with Nichols and Thompson collaborating on adapting Edson’s play to the small screen. By all accounts they didn’t change much. The play’s flashbacks to classroom memories and its surreal shifts in perspective (with the ailing, now bald-headed professor sometimes standing in for her younger self) remain gloriously intact.

What makes Wit more than a weepie is its sophisticated handling of the leading role. Professor Bearing, age 53, is far more than a victim of an unrelenting disease and a sometimes unfeeling medical establishment. In her college classroom, where she lectured undergraduates on the subtleties of 17th century English poetry, she has been a bit of a tyrant, though one who hangs tough out of respect for the poets she introduces. It’s no accident that her specialty is the metaphysical verse of John Donne, who was by turns a bon vivant, a lover, a churchman, and a deep thinker obsessed with a precise use of language. One of Donne’s great themes is the meaning of death, as seen in the famous “Death Be Not Proud,” a sonnet that becomes in this drama an ongoing source of debate. (Even its punctuation, it seems, proves controversial.) Donne also famously weighed the connection between soul and body, which underscores the play’s juxtaposition of a woman concerned for her essence and the medical team’s determination, at all costs, to save her corporeal self. One of the drama’s most powerful moments comes when a sympathetic young oncologist who once earned an A- in Professor Bearing’s poetry course now seeks to overturn every ethical consideration in the name of medical science.

Years ago I saw Wit on the stage and was duly impressed. But Nichols’ TV version benefits from the heightened realism the camera brings, ushering us into a realistic hospital environment and forcing us to watch, up close, as Professor Bearing’s body begins to shut down. In a way that the stage doesn’t much allow, it rubs our noses in the indignities of illness—the ungainly feet-in-stirrups position that most women (but not men) have experienced, the gut-searing bouts of nausea, the casual assaults on basic modesty, the final desperate need for simple solace. One of the play’s most touching moments comes when a former mentor, stopping by to see the patient on her way to visit a great-grandchild, forgets about intellectual rigor and soothes Professor Bearing with a simple children’s book. Mike Nichols’ talent as a director of comedy extends here to the human comedy in all its poignancy.

June 22, 2021

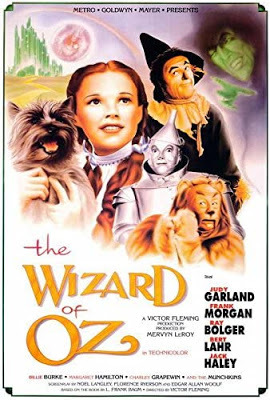

“If Ever a Wiz There Was” – Introducing “The Wizard of Oz” to Today’s Youngsters

I remember when I was small, awaiting my first trip to a local movie house to see a screening of The Wizard of Oz. My mother was excited too, fondly recalling her own youthful introduction to this film classic. My first-ever viewing of The Wizard of Oz occurred long before the advent of color television, with its annual showcasing of the adventures of Dorothy and her friends,, so the return of this film to movie theatres was treated as a really big deal. Newspapers were full of enticing photos of witches and Munchkins. I clipped out a picture of Dorothy meeting the Good Witch Glinda and pasted it into my scrapbook. (Even back then I found Glinda’s outfit a trifle bizarre and her behavior puzzling. Still, my love for the film transcended any qualms I might have about Billie Burke’s weird manner and enunciation.)

I’ve just had the glorious opportunity of introducing The Wizard of Oz to yet another generation, cuddling on the couch with a rather sophisticated nine-year-old boy and a sweet seven-year-old girl who adores animals. Though, especially after a year of quarantine, they’re well accustomed to modern electronic games and can call up kid-friendly movies on their iPads, they were both enthralled by a flick that dates back to 1939. Adrian, who knew the basic story and had seen a stage version, kept up a lively stream of chatter, chortling with delight when one of the movie’s witty lines struck his funny-bone. Among his favorites: the Cowardly Lion’s bold assertion that courage is “what makes the muskrat guard his musk” and that if he were king of the forest it would be “imposerous” to be scared of a mere rhinoceros. And Adrian was duly amused by the unmasking of the fraudulent Wizard, the aftermath of the warning to “pay no attention to that man behind the curtain.”

Mila, newly seven, was not frightened by the film’s many brushes with death. Most of her concern was directed toward her favorite character, Dorothy’s little Scottie dog, Toto. She watched with rapt attention as Toto escaped the clutches of the evil-minded Miss Gulch, and then helped protect Dorothy from Miss Gulch’s Ozian counterpart, the Wicked Witch of the West. (I discovered I had forgotten how often the feisty little Toto saves the day, even being the one who unmasks the phony wizard by pulling aside the famous curtain that reveals the humbug behind Oz the Great and Powerful.) Elsewhere Mila reacted like any 21stcentury child, expressing concern during the opening scenes that the whole picture would turn out to be drab black-and-white. She was disappointed by characters, such as Bert Lahr’s Cowardly Lion, whom she deemed all too obviously human, despite their elaborate costumes and makeup. The whimsy of 1939-style characters can’t measure up, it seems, to the expectations of a child conditioned by CGI miracles.

Still, the morning after she watched The Wizard of Oz, Mila could be heard repeatedly singing, “Ding Dong, the Witch is Dead.” She was a bit puzzled by the Munchkins, but loved the all-green Emerald City, appreciating such inventive moments as the “horse of a different color” who pulls our Oz friends through the streets of the capital. My stories about the making of the film -- Buddy Ebsen being replaced at the last minute by Jack Haley due to his allergic reaction to theTin Man’s silver makeup; Margaret Hamilton risking her life through the untested special effects involved in the witch’s disappearance - -didn’t much interest her because the movie felt too real. Which, of course, it is.

June 18, 2021

Ned Beatty: Delivering One Great Performance After Another

Moviegoers all seem to have their favorite Ned Beatty moments. My colleague Brian Jay Jones (author of biographies of Jim Henson, Dr. Seuss and other pop culture heroes) treasures Beatty’s comic appearance as Lex Luthor’s bumbling sidekick in the Superman movies. Others remember him portraying Judge Roy Bean and playing a key role in All the President’s Men. And of course he had one of the all-time memorable screen debuts, in the movie adaptation of James Dickey’s bestselling novel, Deliverance. As Bobby Trippe, one of four city-dwellers on a rafting trip in the wilds of Georgia, he suffers an excruciatingly painful comeuppance that viewers will not soon forget.

Deliverance came out in 1972. It was followed by some 160 film and TV credits before Beatty’s death last week at age 83. Never a leading-man type, the short, round Beatty was prized as a character actor who could play goofy or scary, strong or weak, with equal dexterity. For years he was known as “the busiest actor in Hollywood.” When I was working at Roger Corman’s Concorde-New Horizons Pictures circa 1990, Roger’s wife Julie was filming a screen version of Gary Paulsen’s classic Young Adult novel, Hatchet. (In the film version, the title was changed to A Cry in the Wild, because Hatchet might give some fans of Corman’s horror flicks the wrong impression.) It’s basically an adventure story about a teenaged boy whose parents have divorced. During his summer vacation, Brian is being flown in a Cessna bush plane to an outpost in the Canadian wilds where his father works in the oil fields. After the pilot has a fatal heart attack and crash-lands the plane, the young boy is stranded in the wilderness, with only his wits and a small hatchet to protect him from danger. The young actor, Jared Rushton, is mostly alone on screen, except for some friendly and some not-so-friendly animals. But I was astonished to see Ned Beatty signing on to play that unfortunate pilot.

On the day Beatty showed up at our grubby offices, I chanced to meet him in the parking garage and couldn’t resist asking a few questions. Like—why would he want a small role in a Concorde film? Beatty explained, with a twinkle in his eye, that he had eight children to support. (He was ultimately married to four different women, with three of those marriages ending in divorce.) He also confirmed what I had read elsewhere, that Deliverance was originally intended by its studio as a relatively low-budget film. Thus all four central roles were to be played by unknowns with regional acting credentials. Beatty, who hailed from Kentucky and had performed all over the South, was cast, as was the equally unknown Ronny Cox. But when the budget was raised to allow for stars in the two biggest roles, Jon Voigt and Burt Reynolds came aboard, replacing the no-names that director John Boorman had selected. Out of such serendipity are great careers born.

Perhaps Beatty’s most distinctive role came in 1976, as part of the film Network. In a landmark year for character actors, he was nominated for an Oscar as Best Supporting Actor, a prize that ultimately went to Jason Robards of All the President’s Men. Beatty’s role is confined to one long speech, a speech of such power and such frightening implications that it remains lodged in the mind. It’s a speech into which author Paddy Chayefsky pours all his vitriol against network television and corporate American in general. Thanks to YouTube we can re-watch it, savoring Sidney Lumet’s staging and Ned Beatty’s dramatic genius.

June 15, 2021

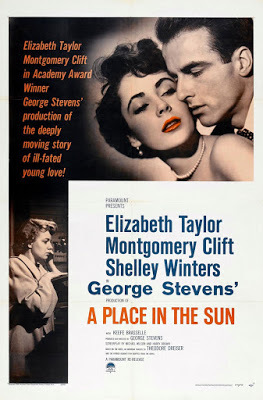

Light and Shadow in “A Place in the Sun”

When, as a lonely young immigrant, Mike Nichols discovered his local movie palace, the film that captivated him was George Stevens’ 1951 romantic tragedy, A Place in the Sun. When the late Charles Grodin considered his future profession, the performance that drew him in was that of Montgomery Clift, as the apex of a lethal love triangle in A Place in the Sun. In the typically bombastic style of the early 1950s, the film’s trailer proclaims: “Never before a film so moving and powerful.” While orchestral music swells, the words on the screen go on to describe the flick as “standing alone as the screen’s most memorable love story.” Hyperbole, of course. But there’s no question that A Place in the Sun has earned its reputation as one of Hollywood’s Golden Age classics. Its six Oscars (including Best Director) are hardly a surprise. More startling, in retrospect, is the fact it was beaten out for Best Picture by the charming but lightweight musical confection, An American in Paris.

Despite its sunny title, A Place in the Sun was shot in black and white, in an era when filmmakers rotated between wide-screen full-color extravaganzas and somber chiaroscuro dramas. (One of the film’s Oscars was for Best Black-and-White Cinematography, while the camerawork of An American in Paris was honored in a separate category.) In this tale of a young man’s relationship with two very different women, one affair takes place in brilliant sunlight, while the other moves stealthily forward in the shadows. It’s not a brand-new story: Oscar-winning screenwriters had adapted it from a 1925 novel by Theodore Dreiser. Dreiser’s work—once considered a classic but not much read these days—was titled An American Tragedy. Based on an actual murder trial, it justified its title by hinting that a young man’s all-powerful desire for wealth and status (even at the expense of honorable behavior) was closely bound up with American values.

In the film, the poor but ambitious George Eastman (Montgomery Clift) comes to town, and immediately lands a position in the factory run by his wealthy uncle. His job is to oversee a group of female workers, with whom he is sternly instructed not to fraternize. Nothing daunted, he begins a secret romance with one of the workers, the plumply pretty Alice (Shelley Winters). But a social evening at his uncle’s palatial home introduces him to a stunningly gorgeous rich girl, Angela Vickers (Elizabeth Taylor at her most beautiful). The sunlit romance with Angela—memorably featuring a day of water-skiing on a local lake—contrasts sharply with George’s nighttime trysts in Alice’s shabby digs. And then Alice reveals she’s pregnant, relying on him to make their romance public, and legally sanctioned. What’s an ambitious young fellow to do?

I won’t go into what happens on that lake, except to say that there’s an unexpected twist. Stevens’ long slow takes and reliance on master shots are hugely effectively, and show up years later in Mike Nichols’ direction of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and other features. And Stevens’ sharp focus on social distinctions and psychological torment make their own powerful statement. For me the classic moment is when George arrives hours late to the sad little one-on-one birthday dinner Alice has lovingly prepared in her rented room. In a long-held shot as they awkwardly converse at the table, her face and body are mostly turned away from the camera. But we can read in her posture all the sadness of a young woman too humbly placed to remain desirable to the man she loves.

June 11, 2021

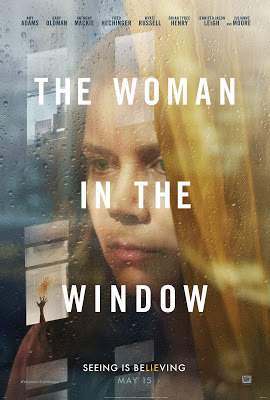

This Lady in Distress . . . is a Mess (“The Woman in the Window”)

Here’s a recipe for a hit movie: take a hot-selling thriller, part of the always-appealing “damsel in distress” genre, then add the choicest ingredients. Like an admired director (Joe Wright of Atonement fame), a screenwriter with a Pulitzer Prize to his credit (Tracy Letts, who also plays a key supporting role), and a full compliment of skilled craftspeople. Then stir in an A-level cast, including Oscar winners like Gary Oldman and Julianne Moore, headed by the always zesty Amy Adams. On top, drizzle a typically tangy Danny Elfman score. Serve luke-warm.

I’m being facetious, of course, The most startling aspect of The Woman in the Window is how many talented people contributed to what turns out to be a dish of leftovers. I haven’t read the popular novel, but the film wants to resemble something by Hitchcock, to the extent of borrowing telling shots from such classics as Vertigo and Rear Window. The plot borrows shamelessly from Rear Window too, combining the idea of a housebound person who witnesses (or maybe witnesses) a crime in the house across the way with that old chestnut: the lady in jeopardy. Since the very beginning of Hollywood, viewers have been titillated by flicks in which a lone female, under the direst of circumstances, must fight for her life against a home invader. See, for example, Barbara Stanwyck as a bed-ridden invalid in 1948’s Sorry, Wrong Number. Sixteen years later, it was Olivia de Havilland trapped in a home elevator in Lady in a Cage. Even in this century the trope has persisted: see Jodi Foster in 2002’s Panic Room. It can be argued that these films are a tribute to female strength in times of adversity: even the weakest, sickliest woman can rise to the occasion when circumstances demand. But The Woman in the Window starts with a woman who’s such a physical and psychological wreck that her eventual heroics are neither convincing nor interesting.

Adams, who was also a painfully hot mess in last year’s Hillbilly Elegy, here plays a child psychologist with a broken family and severe agoraphobia. She takes plenty of meds (washed down with red wine) and has weekly visits from a shrink who makes house calls. And she’s obsessed with the new family across the street from her elaborately creepy Upper Manhattan townhouse. After visits from the weird mother (Moore) and weirder son (Fred Hechinger), she becomes convinced that the father of the family (Oldman) is a killer who’s going to strike again. Alas, no authority figure believes her, especially because there are some gaping holes in the story she tells of her own life. But wait! Why do disturbingly close-up photos of her in bed surface in her email? Maybe something evil DOES this way come. But maybe–just maybe—it’s not the person she suspects.

In Act 3 of this creaky melodrama, there’s the inevitable (and almost endless) fight to the finish. After which a battered and bruised Adams, now cured of her agoraphobia, finally takes off her frumpy bathrobe and blossoms into a strong, whole woman ready to move out of her house of horrors and take on the world. I’m told this film was scheduled for a theatrical release, until the pandemic led it to be presented on Netflix. Under COVID conditions, a TV movie focusing on someone stuck inside makes a grim sort of sense. But frankly, I don’t choose to be confined with the whiny, dreary folks who make up this cast. The New York Times review of this film came up with a nifty headline: “Don’t You Be My Neighbor.”

June 8, 2021

Moving from Back to Front in “Snowpiercer”

There was a time, before Parasite, when I had never heard of the Korean director Bong Joon-Ho. But 2019’s Parasite made such an impression on me – and on the film community – that I was eager to know more. Parasite, of course, was the first foreign-language film ever to nab the Oscar for Best Picture, as well as winning honors for its direction and screenplay. The film’s twisty look at the contemporary class struggle, one that swings between comedy and tragedy while encouraging us to continuously shift our sympathies between the story’s two main families, has made me realize that this is a film to be savored more than once, and perhaps viewed differently on each viewing.

No, I haven’t had the chance to view it again. But recently I watched a Bong Joon-Ho production from 2013, one that I’d seen advertised on theatre marquees in far-flung cities, back in the long-ago days when travel seemed our birthright. Snowpiercer is in fact a film that depends on the idea of travel, but hardly travel for fun or cultural stimulation. The characters in Snowpiercer (based on a French graphic novel) travel ceaselessly because they have to. An ambitious attempt to stem global warming – certainly a hot topic at the moment – has backfired into a global ice-age so severe that no living thing can survive outdoors. Those people who’ve managed to save themselves are crowded aboard a long, powerful train that circumnavigates the earth without stopping. Its inventor and chief engineer, the mysterious Wilford, has become, in the seventeen years since the catastrophe, viewed as humanity’s benefactor and ultimate savior.

The film’s opening scenes take place in the rear of the train, where an international group of passengers (mostly speaking English) suffer from malnutrition and other woes. Over the course of seventeen years, relationships have formed and babies have been born. But the squalor is intense, helped along by an ad hoc military clique that hands out grim-looking rations while stamping out any signs of plebeian rebellion among the passengers. The scariest figure, Mason, is played by Tilda Swinton, in a wig, false teeth, owl-eyed glasses, and a chest full of medals. She issues commands and threats, while sternly reminding everyone of Wilford’s benign generosity.

Despite the dangers posed by open insurrection, a number of passengers (Chris Evans, Jamie Bell, and Octavia Spencer among them) are poised to fight their way to the front of the train. That’s when director Bong pulls one of his trademark surprises. The grimy, tightly-packed cars at the rear of Snowpiercer suddenly give way to a kind of fantasyland on wheels: a cozy schoolroom, a swanky beauty salon, an orchard in full bloom, an aquarium full of exotic fish, a sushi bar with all the trimmings. And perhaps the biggest surprise of all is discovered by Evans’ character when he’s invited to meet Mr. Wilford in the flesh. At this point the tale becomes something of a philosophical treatise on class structure, one containing some revelations we doubtless didn’t expect.

This is an ambitious and by no means perfect film, though seeing it on a screen much larger than my home TV set would certainly help. There’s so much going on here that it’s hard to keep track of the many characters and their situations, so that key basic plot points can be elusive. But Bong’s ironic affection for humanity – despite it all -- is very much intact, and the film’s ending, beautifully shot, lingers in the mind. This is a world of fire and ice I won’t soon forget.

June 4, 2021

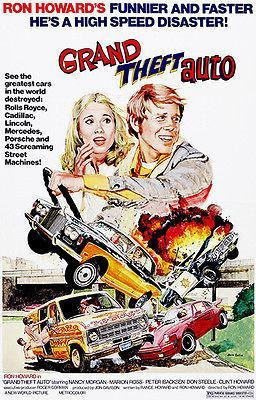

Ron Howard Pops His Clutch in “Grand Theft Auto”

Back in the days when Ron Howard still had hair, he knew he wanted to graduate from acting roles into the director’s chair. Sure, he’d won the hearts of the nation while playing a red-headed moppet named Opie on The Andy Griffith Show. Then, having passed through the difficult teen years that all child-actors dread, he emerged as the star of American Graffiti and, soon thereafter, TV’s long-running Happy Days, which made him a heartthrob to pubescent girls. But along the way he’d become intrigued with the idea of directing, even (as a high-schooler) winning $100 in a Kodak contest for an original short film called A Deed of Daring-Do, in which a young boy (played by brother Clint) imagines himself the hero of a movie western. (Before he agreed to star in Ron’s film, the always rambunctious Clint had demanded 50% of the gross and when the money came Ron was forced to cough up half of his prize money.)

Although by 1976 Ron Howard was a genuine TV star, no studio chief wanted to hire him as a director. Enter my former boss, Roger Corman, at the rough-and-ready New World Pictures. He was after Ron to star in a teen car-crash flick called Eat My Dust, to be directed by Corman veteran Charles B. Griffith.. Most young actors starring in hit sitcoms would not have jumped at the chance to make a Corman cheapie, but Ron saw Eat My Dust as a golden opportunity. He told Roger he’d agree to appear if it led to the opportunity to direct a later film. To make a long story short, Eat My Dust led to Grand Theft Auto, with Ron directing as well as starring, from a script he’d crafted with his father Rance.

There aren’t many young men, on the brink of a major career move, who’d be willing to collaborate with their dads. But the Howards prized professionalism as well as family loyalty: father and son were equal partners in the writing process, and both Rance and Clint Howard took on featured roles, along with such friends of the family as Garry Marshall and Marion Ross of Happy Days fame. And Ron’s wife Cheryl stepped in at a key moment when the crew was about to mutiny over the terrible chow served during the Antelope Valley location shoot. Commandeering a relative’s local kitchen, she whipped up enticing meals for 85 hungry movie-makers.

The story of Grand Theft Auto is rollicking and complicated: a young man named Sam Freeman (Howard) and his wealthy girlfriend Paula decide, over the objection of her parents, to get married, so they hijack her daddy’s Rolls Royce and take off for Las Vegas. Soon they’re being hotly pursued by angry parents, a snooty would-be fiancé, some cops, a phony preacher, a radio DJ, and all manner of other folk, culminating in a demolition derby at a Las Vegas racetrack. As a twenty-two-year-old newbie director well aware he was not making Citizen Kane, Howard worried that he wouldn’t be respected by his cast and crew. But others marveled at Ron’s ability to stay cool, and to use his considerable organizational skills to manage a paltry budget. Second-unit director Allan Arkush, who was filming car-crashes at the same time that Ron was shooting dialogue scenes, remembers that, unlike in a major studio film, “you literally had one costume per character. You couldn’t let the stuntman have the entire outfit.” So Ron’s advance planning helped them always know “where are the pants gonna be at four o’clock?”

I learned all these stories while researching my biography, Ron Howard: From Mayberry to the Moon . . . and Beyond. It was published in 2003, but this year has appeared for the first time in an audiobook format. If you’re interested, and are one of the first to write to me at beverly@beverlygray.comwith the words “Ron Howard audiobook” in the subject line, you may win a free link to the brand-new audiobook. Such a deal!

My recent interested in Grand Theft Auto was sparked when I was invited to guest on the delightful B-Movie Cast podcast. Here’s how to give this segment a listen:

June 1, 2021

Down and Out in Beverly Hills: “Sunset Boulevard”

Sunset Blvd. is one of the most memorable thoroughfares in SoCal, winding graciously from the Pacific Ocean through the leafy residential neighborhoods of the very rich and on to the glitz of the Sunset Strip. And Sunset Blvd. is one of the most memorable movies ever to come out of the Hollywood studio system. Part of why it resonates is because director (and co-writer) Billy Wilder, after years of churning out stellar films like Double Indemnity and The Lost Weekend, knew everything about that system. His shelf full of Oscars and other awards gave him the confidence to bite the hand that had fed him nicely since he emigrated from Germany one step ahead of the Nazis in 1938. Before I watched the film again recently, I had forgotten all the little pokes Sunset Blvd. takes at studio bosses, like the producer who admits he turned down the chance to film Gone With the Wind because he figured no one cared about the Civil War. And then there’s the young director who’s so ignorant about the legendary silent star Norma Desmond that when she visits the Paramount lot he’s only interested in renting her vintage limo to use in his next picture.

But if most studio types don’t come off well in Sunset Blvd., the film is fundamentally more interested in those at the very top and at the very bottom of the above-the-line food chain. At the top are the stars, those ethereal but rock-hard creatures so beloved by their public that they can get away with pretty much anything, including shrugging off those who helped them in their climb to success. One such is Norma Desmond (the unforgettable Gloria Swanson) , a silent-era queen of cinema who now employs the director who’d discovered her as a manservant in her crumbling Beverly Hills mansion. The fact that he also happens to be her former husband reminds us that stars feel entitled to use people and move on.

One problem with stars, though: they generally have a lights-out date. They grow older and less beautiful: in Norma’s case the coming of talkies introduced an entirely different style of acting, one dependent as much on verbal dexterity as on facial expressions and pantomime. Starting in the 1930s the role of screenwriters changed too, with many bright young men (and a few women) imported from the east to add literate sophistication to studio films. That’s how former Dayton, Ohio newsman Joe Gillis (William Holden) showed up in SoCal, only to find himself trading his soul for the occasional studio paycheck. Here he is describing his most recent picture: “Last one I wrote was about Okies in the Dust Bowl. You'd never know because when it reached the screen, the whole thing played on a torpedo boat.”

Billy Wilder knew a thing or three about studio-mandated script changes, and about how writers in Hollywood both love and hate a system that abuses them without shame. He also, surely, knew something about faded stars. A current screenwriting student of mine, Paul Blyskal, commented recently about the film’s most famous Norma Desmond line: “I am big! It's the pictures that got small.” To Paul “the tone of the line is simple and proud. But it also resonates as deeply unhinged. And it contrasts beautifully with Joe Gillis' style of self-presentation. He is no less ambitious about his future, but his ambitions are more disguised and presented less confidently, buried under vacillations and self-deprecations, offered with the pretense that he doesn't really want what he wants. Norma Desmond isn't ashamed of what she wants.”

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers