Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 48

March 16, 2021

“The Prestige” and “The Greatest Showman”: Hugh Jackman Struts His Stuff

Hugh Jackman has had a varied career on both stage and screen. He’s ranged from singing the lead in Oklahoma! to flashing his claws as Wolverine. Though often cast as a nice guy, he effectively revealed an oh-so-devious side as a Long Island school superintendent in TV’s 2019 drama, Bad Education. But his personal brand of panache really comes forth in two movies from earlier in this century. In both The Prestige (2006) and The Greatest Showman (2017), he has the opportunity to shamelessly strut his stuff, reveling in his talent for self-display. One is a serious drama and the other a musical. Both have their moments, but both are ultimately maddening to experience.

Hugh Jackman has had a varied career on both stage and screen. He’s ranged from singing the lead in Oklahoma! to flashing his claws as Wolverine. Though often cast as a nice guy, he effectively revealed an oh-so-devious side as a Long Island school superintendent in TV’s 2019 drama, Bad Education. But his personal brand of panache really comes forth in two movies from earlier in this century. In both The Prestige (2006) and The Greatest Showman (2017), he has the opportunity to shamelessly strut his stuff, reveling in his talent for self-display. One is a serious drama and the other a musical. Both have their moments, but both are ultimately maddening to experience. I was surprised to discover that in The Prestige, Jackman was billed on screen ahead of Christian Bale (who had not yet, of course, won an Oscar). The two play arch-rival illusionists plying their trade in Victorian England, with Jackman so obsessed with learning the secret behind Bale’s “transported man” finale that he sacrifices everything (including the love of Scarlett Johansson) to attain his goal. It’s a jolly good premise for a drama, with lots of angst and stage trickery to tantalize the viewer, and I admit it builds to quite a smashing conclusion, based on a very clever, very unexpected reveal. (The term “the prestige,” we’re told at both the beginning and the end of the film, refers to the surprise third act of a stage magician’s every trick.)

The problem? I suspect we have to blame it on Christopher Nolan, who both co-wrote and directed The Prestige after Memento and before The Dark Knight. The film is an adaptation of a British novel, but I gather Nolan couldn’t resist adding his own creative touches. One is the introduction of Tesla (the scientist, not the car), whose contribution to the plot still has me baffled. By participating indirectly in Jackman’s character’s ultimate stage act, Tesla apparently enables a real-life miracle that is key to unlocking some of what we see at the end of the film. Unfortunately for me, the key didn’t fit any lock I could find. It’s no fun watching a movie, however twisty it might be, in which one ends up saying, “Huh?”

If The Prestige is overly complicated, The Greatest Showman is overly simple. Jackman must have believed strongly in this material, because he’s credited as one of the film’s producers. But this super-streamlined life of P.T. Barnum is predictable from the get-go. There’s some imaginative staging, but the characters are two-dimensional: what a waste of the talented Michelle Williams as Barnum’s ever-loving wife! I’m a fan of movie musicals, but the songs here seem to keep striking the same note: lots of anthems about the importance of dreams, and magic, and community, and self-respect. (OK, there’s one rousing choral number, the Oscar-nominated “This is Me,” ebulliently sung by the freaks and geeks of Barnum’s circus. Frankly, I’m not sure what I think of the basic message that physical deformity is cool. Anyway, didn’t the real Barnum exploit –rather than exalt – these social outcasts?)

As for Jackman, he sings, he dances, he struts, he romances his wife and tickles the fancy of his adoring children: through it all, he seems to be having a simply marvelous time. I’m told that a lot of the original moviegoers left the theatre very happy indeed. For me, on the other hand, the final fadeout (following a bigger-than-big final number) was a blessed relief. Next time, I’ll avoid the bombast and stick to Hugh Jackman as a suave but surreptitiously deadly school administrator.

March 12, 2021

Brand Recognition and Sequelitis: Coming 2 America

For those who like silliness laced with social satire, Eddie Murphy’s 1988 hit, Coming to America is hard to beat. As everyone knows by now, it tells the tale of a pampered African prince (from the totally imaginary kingdom of Zamunda) who flies off to Queens, NYC, to find a bride who will love him for himself. The satire encompasses jokes about naïve royal expectations as well as a clear-eyed view of life among African-Americans in a jolly but grubby New York slum. Some sequences still tickle my funny bone: I love the John Amos character, a Black American entrepreneur trying to rip off McDonald’s by copying its signature brands and logos for his own McDowell’s burger joint. (His nouveau-riche digs contain, hilariously, copies of famous Impressionist paintings in which the subjects are transformed by African skin tones.) And I chuckle at the moment when Eddie Murphy’s Prince Akeem takes his new American girlfriend home to his squalid Queens flat, hoping to win sympathy for his pathetic immigrant lifestyle, only to discover that best buddy Semmi (Arsenio Hall) has suddenly transformed the place with neon sculptures and a hot tub. Perhaps most hilarious of all are the flashy costumes (by Oscar-nominee Deborah Nadoolman) that project the self-confidently wacky Zamunda spirit.

For those who like silliness laced with social satire, Eddie Murphy’s 1988 hit, Coming to America is hard to beat. As everyone knows by now, it tells the tale of a pampered African prince (from the totally imaginary kingdom of Zamunda) who flies off to Queens, NYC, to find a bride who will love him for himself. The satire encompasses jokes about naïve royal expectations as well as a clear-eyed view of life among African-Americans in a jolly but grubby New York slum. Some sequences still tickle my funny bone: I love the John Amos character, a Black American entrepreneur trying to rip off McDonald’s by copying its signature brands and logos for his own McDowell’s burger joint. (His nouveau-riche digs contain, hilariously, copies of famous Impressionist paintings in which the subjects are transformed by African skin tones.) And I chuckle at the moment when Eddie Murphy’s Prince Akeem takes his new American girlfriend home to his squalid Queens flat, hoping to win sympathy for his pathetic immigrant lifestyle, only to discover that best buddy Semmi (Arsenio Hall) has suddenly transformed the place with neon sculptures and a hot tub. Perhaps most hilarious of all are the flashy costumes (by Oscar-nominee Deborah Nadoolman) that project the self-confidently wacky Zamunda spirit. The film came out more than 30 years ago, so why the sudden need to produce a sequel? I’m not sure, though Murphy’s career (he’s now 60) is not as bright as it once was. And we can always use a good laugh. Still, the times they are a-changing, and what seemed fresh and funny in 1988 may feel more strained now. This story’s attempt to live up to current sensibilities (e.g. in the recognition that women too deserve empowerment) is little more than a wink and a nod toward the evolving attitudes of 2021. But my chief problem with the film is that—in the way of most sequels—it is basically a recycling of greatest hits for fans of the original.

In one respect, Coming 2 America doesn’t falter: the outrageous glad rags designed by Ruth E. Carter (who made history by winning Oscar recognition for her work on Black Panther) evoke the spirit of the original film, but takes the buoyant garishness of Zamunda’s royal court even further into the stratosphere. And I enjoyed seeing once again the great James Earl Jones, who as King Jaffe Joffer is both an autocrat and a benign presence. His death scene, following the most extravagant of all funerals (he wanted to enjoy it while still living) is among my favorite of the movie’s goofy moments.

Still, Coming 2 America is mostly a rehash of tropes from the previous movie. There’s a twist on those bathing maidens that’s easy to anticipate, and the geezers from the barbershop are back, with the inevitable (not all that funny) Yiddish shtick from a well-disguised Murphy inserted at the end of the credit sequence, just like in the original. Gags we remember from Coming to America are plugged into the current storyline, which tries for variety in that it’s the previously unknown SON of Eddie Murphy who’s now the naïf trying to figure out where his princely heart is taking him. The bizarre circumstances of this son’s conception will surely leave a bad taste in some mouths, but the movie’s not prepared to get serious about anything that might distract from the desired hilarity. Coming 2 America, in other words, falls into the trap of other sequels to hit films: it wants to give the audience the same thing as before, only different.

March 9, 2021

Mother Knows Best?: “Now, Voyager” and “Miss Juneteenth”

In Now, Voyager, Bette Davis is displayed like a rare jewel. Dressed in sleek Orry-Kelly suits, fabulous face-framing hats, and shimmering evening gowns, she radiates sophisticated charm. But when we first meet her in this classic 1942 melodrama, she’s a dowdy spinster, wearing a drab housedress, thick glasses and a frightened look. She’s in this frumpy state because she’s in thrall to her dowager mother, a ferocious old tyrant played by Gladys Cooper. Mrs. Henry Vale, of the Boston Vales, is a wealthy, imperious snob, one who takes pride in the family’s lineage and feels there are few outsiders who can equal it. Daughter Charlotte (Davis’s character) is her late-in-life child, cursed with the obligation to be her mother’s companion and caregiver. For her efforts, she is constantly belittled, made to feel she’ll never measure up to the standards that previous Vales have set.

In Now, Voyager, Bette Davis is displayed like a rare jewel. Dressed in sleek Orry-Kelly suits, fabulous face-framing hats, and shimmering evening gowns, she radiates sophisticated charm. But when we first meet her in this classic 1942 melodrama, she’s a dowdy spinster, wearing a drab housedress, thick glasses and a frightened look. She’s in this frumpy state because she’s in thrall to her dowager mother, a ferocious old tyrant played by Gladys Cooper. Mrs. Henry Vale, of the Boston Vales, is a wealthy, imperious snob, one who takes pride in the family’s lineage and feels there are few outsiders who can equal it. Daughter Charlotte (Davis’s character) is her late-in-life child, cursed with the obligation to be her mother’s companion and caregiver. For her efforts, she is constantly belittled, made to feel she’ll never measure up to the standards that previous Vales have set. Thankfully, a kindly psychiatrist sympathetic to Charlotte’s plight helps spring her from this house of horrors and convinces her of her own worth. She cultivates a sense of style and, on a “recuperative” South American cruise, discovers she’s capable of loving and being loved. Eventually, though, she must return to her mother’s house, where Mama expects her to fit back in to her old life. (There’s a bit of a twist at the ending, but let’s not spoil things.)

I thought of Now, Voyager after having watched the 2020 Sundance hit, Miss Juneteenth. At first glance, the two flicks couldn’t be more different. Though Now, Voyager is set among Boston Brahmins, Miss Juneteenth takes place in a suburb of Fort Worth, Texas, where young African American girls vie to win the title of Miss Juneteenth, an honor that comes with a college scholarship and a full load of expectations. Turquoise Jones won the pageant in 2004, on the strength of her natural beauty, her smarts, and a dramatic reading of Maya Angelou’s poem, “Phenomenal Women.” Now she wants her daughter, 15-year-old Kai, to follow in her footsteps, even to the extent of reciting the very same inspirational poem. Kai, needless to say, is not exactly enthused. Both films, then, depict mothers pressuring their daughters to live up to their expectations, and to accept maternal standards as their own.

Big difference, though: Miss Juneteenth is far less about a daughter’s muted rebellion than about why Mama is so desperate to lay down the law. Yes, Turquoise won that competition in 2004, but she has not gone on to the worldly success that the judges had predicted for her. Her future was derailed by love, and by an early-arriving baby. No, as a single parent, she works two jobs, as the manager of a local bar and as the cosmetician making up stiffs at the local black mortuary, so that her daughter can have a bright future of her own. Given her thwarted expectations, it’s no surprise that Turquoise dreams of better for Kai. Her determination that her little girl succeed at all cost, though, threatens to derail what has always been a close mother/daughter bond.

In the Disney Princess version of this story, Kai would certainly be crowned Miss Juneteenth. (The title refers to the historic day -- June 19, 1865 – when news of Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation finally reached the state of Texas.) In this appealing indie, Kai makes her mother proud while essentially striking out on her own. But the movie belongs to Turquoise who, in its final moments, is finally on track to finding her own adult success. She’s not exactly the glamorous Bette Davis, but she too is reaching for the stars.

March 5, 2021

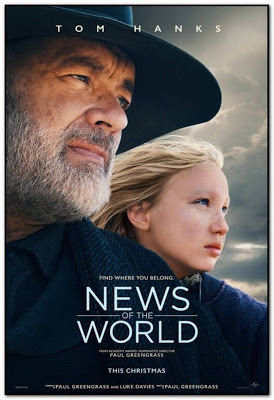

All The News We’d Want to Print: “News of the World”

Tom Hanks may be a national treasure, but it’s easy to get a bit blasé about his movie roles. He’s so readily identified as a decent man, a true Mister Rogers of the screen, that we tend to sell him short. Which is why, I suspect, few people rushed to watch News of the World under COVID conditions, especially those of us who had to pay serious money ($19.99) for an at-home Amazon Prime rental. Yes, this film is Hanks’ first western, but it’s natural to feel that we’ve seen it all before, though with Hanks now wearing a six-gun and appropriate clothing. And when we learn that much of the film is Hanks’ character, a Civil War captain, trying to communicate with a little girl who doesn’t understand English, we’re apt to see this as a repeat of Hanks in Cast Away, in conversation with a volleyball. In other words, the good but lonely man, struggling to get by under trying conditions.

The latter is quite true, but the film still has a lot to recommend it. James Newton Howard’s musical score is evocative, and Dariusz Wolski’s cinematography makes the old west come alive. (New Mexico, a popular filming location in recent years, vividly stands in for Texas.) There’s a fascinating glimpse of the life of a news-reader, an educated but itinerant fellow who roams the countryside, charging ten cents to locals who enjoy hearing him read stories, colorfully embroidered, drawn from daily newspapers. And director Paul Greengrass, known for United 93 and several Jason Bourne films, has always been good at ramping up tension. After a year of pretty much being hidden away at home, I responded strongly to the lure of wide-open spaces.

But the heart of News of the World lies in the character played by Hanks. As portrayed, he’s something of a man of mystery. A Texan by birth, he fairly obviously fought on the southern side of the War Between the States, but it’s not at all clear where he stands on the great social issues that fostered the conflict. (This ambiguity is cagey on the filmmakers’ part: we don’t want to imagine a Tom Hanks character fighting for the side that supported slavery.) He wears a wedding ring, but his marital situation remains tantalizingly ambivalent, especially after a kindly innkeeper who seems to know him well points out that he should not keep skirting a return to his home turf. It’s not until late in the movie that the pieces all fall into place, allowing us to know what he’s about as he wends his way across the western landscape.

Of course it’s that little blonde girl (played by 12-year-old German actress Helena Zengel) who makes all the difference. From the first time he spots her, Hanks’ Capt. Jefferson Kyle Kidd grasps something of her situation: she was abducted from her family home at a tender age and raised among the Kiowa. It is their buckskin clothing, their behavior, and their language she clings to, unwilling to accept any other family. Of course her relationship with Kidd will evolve, but her situation (not entirely uncommon in the old west, as history tells us) understandably makes us think of a similar plot strand in John Ford’s iconic The Searchers. In that 1956 classic, it’s Natalie Wood who’s been raised among the Indians who massacred her parents, with John Wayne trying to bring her back to “civilization.” Big difference: Wayne’s character is an Indian-hater incapable of empathy for a young girl’s cross-cultural plight. Tom Hanks is just not that kind of guy.

March 2, 2021

Talking Sense, with Sensibility

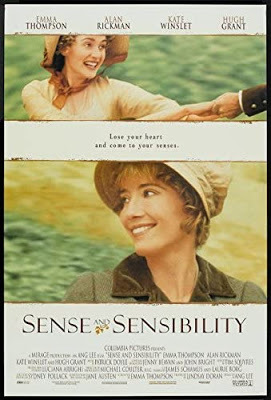

I don’t think Emma Thompson is stressing about it, but I continue to feel that I owe her an apology. It all dates back to 1995, when (after leaving Roger Corman’s Concorde-New Horizons Pictures), I was desperately scrounging for work in the film industry. For a brief, miserable period, I served as a reader for a big recording label that was trying to work its way into films. In that pre-Internet era, being a reader was a miserable job, and I doubt it’s changed very much since,, aside from the fact that a screenplay PDF can now arrive automatically in your in-box. My job was to rush bright and early to the company’s headquarters, grab the screenplay that had been assigned to me, then race home. I had about six hours to read the script and fill out a detailed report outlining the basic plot and evaluating the strengths of the writing. By 4:30 p.m. I needed to be back at the same office, dropping off the fruits of my labors. I’d been warned in advance that company executives had no time to waste: I was expected to be as tough as possible on everything I considered.

So . . . one day I was assigned Emma Thompson’s first screenplay, an adaptation of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility. This was intended as a writing sample: the film was in process of being made by another company, but it was my job to evaluate whether Thompson should be considered as a screenwriter for future gigs. As a PhD English major I had read my share of Austen, and loved her witty slant on romantic life in the early 18th century. I enjoyed Thompson’s screenplay too, but I obeyed my mandate to be a stern critic. I didn’t feel too bad, back then, about the harshness of my complaints: Thompson was already an Oscar-winning actress, and I didn’t think I’d ruin her life by dissing her talents in another field.

I soon gave up on the indignities of being a reader, a dead-end job if there ever was one. Sense and Sensibility (starring Thompson, Kate Winslet, Hugh Grant, Alan Rickman and many of Britain’s finest) turned out to be a major hit. It was nominated for seven Oscars (including best picture) and won for Thompson’s screenplay. She was also honored by the Writers Guild of America, as well as by the literary folks attending the annual USC Scripter Award presentation. The Scripter competition gives prizes to the best screen adaptation of an existing literary work. Normally, both the screenwriter and the author of the original material are feted. At USC, actress-turned-author Fannie Flagg read a letter purporting to be from Jane Austen herself, praising Thompson’s work and crowing that the Brontë sisters would doubtless be jealous to have missed out on similar accolades. (Thompson had her own fun being Jane at the Golden Globes presentation –see below.)

As for me, I continued to think ill of Thompson’s Sense and Sensibility adaptation until I re-read Austen’s novel and then sat down with The Sense and Sensibility Screenplay and Diaries, published by Thompson in 1996. Thus prepared, I was able to see what a very smart, sensitive job Thompson had done of simplifying Austen’s complex language and plotline without losing the essence of her concerns. I understood for the first time what she had wisely left out, and (equally important) what she had added: like giving the youngest Dashwood daughter a personality and interests that richly enhance her sister’s evolving romance. I’m late in saying it, but Brava, Ms. Thompson!

February 25, 2021

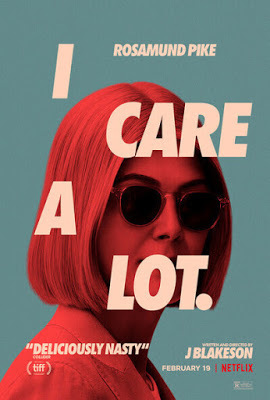

I Care A Lot . . . About Seniors in the Movies

As a woman of a certain age, I’m starting to become sensitive to the way older folks are portrayed on screen. I’m annoyed when ageing baby boomers are depicted as “cute,” or (worse yet) pathetically out of touch. I appreciate the fact that Liam Neeson, at 68, regularly kicks butt in his flicks. And I love the on-screen moral and intellectual strength shown by such actresses as 75-year-old Helen Mirren, 71-year-old Meryl Streep, and 86-year-old Judi Dench.

Which leaves me of two minds about a new movie on Netflix, I Care A Lot. The film is intended as a thrill ride, in which viewers are never quite certain on which side to be, and in that respect (despite some pretty large plot-holes) it certainly measures up. One curious thing: both writer/director J Blakeson and star Rosamund Pike are British, so I’m not quite sure why the setting of the story and the nationality of its cold-as-ice main character are made distinctly American. Is it a Brit’s comment on American naïveté, or the depths of American chicanery? Or is the film showcasing, perhaps, the failure of American social institutions to protect themselves against unscrupulous con artists?

In any case, the opening of the film will strike fear in the heart of anyone old enough to qualify for an over-65 COVID vaccine. It seems that Pike’s character, the attractive and well-kempt Marla Grayson, knows just how to find seniors with money and no intrusive family connections. With the help of an unprincipled doctor, a blindsided judge, and several others in on the scheme, she proclaims a medical emergency, gets herself appointed her target’s legal guardian, and has the victim hustled off to a “convalescent home.” While her numerous charges waste away behind locked doors, plied into compliance with heavy-duty meds, she sells their houses and empties their safe deposit boxes, all in the name of providing funds for their ongoing medical care.

The drama heightens, of course, when she picks the wrong victim, Jennifer Peterson (played by the always appealing Dianne Wiest). Jennifer is by no means helpless—she’s a successful businesswoman in her early seventies who owns a charming home and has a full slate of activities—but within minutes Marla has presented an emergency court order and whisked her off to a facility that quickly relieves her of her cellphone and other ties to the outside world. She seems beyond help. But wait! Jennifer has a secret personal connection that will not tolerate her disappearance, and has the muscle to do something about it.

From there the story twists and turns, reveling in lurid dramatic clichés. Maniacal lesbians! Blood-thirsty members of the Russian mafia! Peter Dinklage throwing giant-sized temper tantrums! Several important characters get left for dead, but recover completely (this is definitely a gang that can’t shoot straight). I didn’t buy a lot of it, but there’s no question this story is entertaining, if you like mayhem and deceit. Particularly strong is what happens between Marla and her #1 foe, who bury the hatchet in a way that I didn’t see coming.

And yet . . . I deplore watching Dianne Wiest in the role of an ageing but still vigorous woman who needs to be rescued by men. Aren’t we long past The Perils of Pauline? It’s progressive, I guess, to show a woman who’s capable of being a kingpin and a villain, but why can’t another woman—an older woman—be the one to trip her up? Maybe it’s just me, but wouldn’t it be nice to see a thriller in which a seventy-year-old female kicks butt?

February 23, 2021

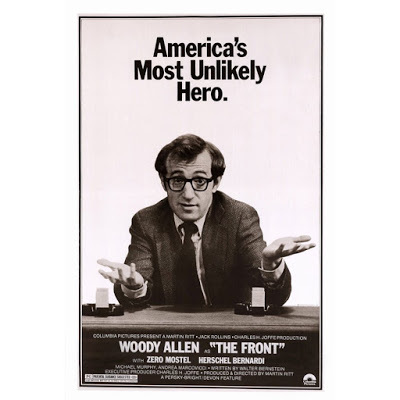

Woody Allen: An Everymensch Steps to the Front

These are not easy times for Woody Allen. This month’s release of a four-part TV documentary, Allen v. Farrow, casts his behavior toward his then-seven-year-old adoptive daughter Dylan in the worst possible light. The series was made by the much-honored documentarians Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering, who have both earned a reputation for getting ugly things right. I’m hardly a Mia Farrow enthusiast, and some of her son Ronan Farrow’s journalistic crusades strike me as grandstanding. But the story of Allen’s troubling behavior toward Dylan—which he continues to hotly deny—leaves little question that Woody Allen’s once brilliant filmmaking career is essentially over.

For someone who loves Annie Hall, delights in the goofy pleasures of the early Allen canon (Sleeper, Bananas, Take the Money and Run), and respects the moral complexities of later films like Crimes and Misdemeanors, it’s sad indeed to see a professional reputation destroyed by personal bad behavior. Allen’s case is hardly unique, though: plenty of great artistic talents were heinous individuals. What complicates Allen’s situation, though, is that he can’t easily be divorced from his work. When we look at a brilliant Gauguin painting, we don’t need to focus on the fact that during his romantic Tahitian sojourn Gauguin apparently spread syphilis throughout the islands. But to watch a Woody Allen film is to watch Allen himself, in the fairly unchanging role of a lovable nebbish, one who’s shrewd but not wise, who frequently screws up but is still able to retain our sympathy. In other words, an everymensch.

Those thoughts crossed my mind as I watched Allen’s performance in the rare Allen film he did not write or direct. The Front is a 1979 movie that takes us back to 1953, that unfortunate time when—thanks to the dark machinations of some power players in Washington DC—lives were destroyed because of past beliefs and associations. During what we now call the McCarthy Era, Hollywood was especially hard hit. Actors, directors, and particularly screenwriters were banned from pursuing their craft, or lived in fear that they’d be denounced in front of a congressional committee. Two and a half decades later, the late Walter Bernstein wrote The Front, and Martin Ritt directed it. Both had been blacklisted back in the day, as had featured actor Zero Mostel and several of the others taking part. And the script contains such grim true-to-life incidents as a beloved but suddenly unemployable performer hounded into suicide.

In the midst of this disastrous situation, Allen plays a ne’er-do-well cashier (and sometimes bookie) who’s a longtime pal of a blacklisted TV writer. For a 10% cut, he agrees to put his name on his friend’s brilliant new pilot. Suddenly, he’s the hottest scribe in the industry, especially after two more blacklist victims beg him to front for them as well. All this attention means he’s expected to show up at meetings and generally air his genius. It’s a fascinating role for Allen: as a man living (and profiting hugely from) a lie, he’s trying to wiggle his way through a moral dilemma without giving up too much of his newfound creature comforts, which include a politically idealistic TV-exec girlfriend.

Woody Allen in The Front gets to call upon a lot of his trademark Woody-isms: the thick glasses, the hapless air, the stammer. He’s not the real Allen (he says at one point he can hardly write even a grocery list) but he sure looks and sounds like the Allen we know and love. Or do we really know him? Regarding who he really is, will we ever be sure?

February 19, 2021

The Brothers Mankiewicz: From “Horse Feathers” to “Sleuth”

As a film buff, I knew that more than one Mankiewicz had made his mark in show biz. Apart from younger generations (one the late president of National Public Radio, one currently a host on Turner Classic Movies), there were two patriarchs who dated back to the Golden Age of the Hollywood studio system. One of them, Herman J. Mankiewicz (1897-1953) worked with the Marx Brothers and won an Oscar in 1942 for the screenplay of Citizen Kane. His younger brother, Joe (1909-1993) kept so busy as both a writer and a director that it’s hard to keep track of his diverse accomplishments. Suffice it to say here that he both wrote and directed a backstage classic, 1950’s All About Eve.

One Mankiewicz has been in the spotlight lately because a new film about him, Mank, has been scooping up Golden Globe nominations and other prizes. This ambitious work by director David Fincher, working from a long-gestating screenplay by his father Jack, focuses in on curmudgeonly Herman—his leg encased in plaster following an auto accident—lying in bed at an out-of-the-way Palm Springs bungalow. While trying half-heartedly to stay off the sauce (he’s a legendary alcoholic), he’s struggling to concoct the beginnings of the Citizen Kane screenplay, while John Houseman runs interference between Mank and boy wonder Orson Welles. Emulating the elaborate flashback structure of Welles’ famous debut film, Fincher hops between Mank on his sickbed and his memories of past madcap dinners at San Simeon with William Randolph Hearst (who was to become the model for Charles Foster Kane) and his spirited sweetheart, Marion Davies. It’s a bold idea, and one that lends itself to gorgeous black and white cinematography along the lines of Gregg Toland’s legendary work on Kane. But Fincher muddles matters by digressing into MGM studio politics and Louis B. Mayer’s sabotaging of Upton Sinclair’s run for the California governorship, issues almost wholly peripheral to the story of Mank and Citizen Kane (which was made by RKO).

I’d much rather get my Mankiewicz family history from a smart new biography by my colleague, Sydney Ladensohn Stern. Her The Brothers Mankiewicz puts the brothers’ lives in context, exploring their German-Jewish immigrant roots and the impact of their strong-minded father on their own life choices. There’s plenty of Citizen Kane lore to be found between these pages. I learned that Herman’s loss of a childhood bike probably led directly to Kane’s famous sled. Also, that the moment when Kane finishes up Jed Leland’s scathing review of Mrs. Kane’s operatic debut as Leland himself would have written it probably evolved from Mank’s own early newspaper career, when his editor at the New York Times took over the review of a vanity project he himself was too soused to complete.

But much of Stern’s book belongs to the long-lived Joe Mankiewicz, who became a film director almost despite himself. Blessed with the family wit, he was doing well as a screenwriter when he was drafted into the director’s chair, first at Fox and later for other studios. He’s perhaps not better known for his directorial skills because he’s hardly an auteur type: his films run the gamut from social comedy (A Letter to Three Wives) to tense racial drama (No Way Out), from Shakespeare (Julius Caesar) to Broadway musicals (Guys and Dolls). Doubtless All About Eve (which won six Oscars, two of them for him) was his best experience. The worst was surely the 1963 behemoth Cleopatra, which was wracked by budget problems, logistical nightmares, an unfinished script, and (of course) a love affair that filled the tabloids.

February 16, 2021

“Bridgerton”: Enticing Anachronisms and Angst

Somewhere out there, Jane Austen is surely giggling. Bridgerton, a TV dramatic miniseries that is both mesmerizing and completely cuckoo, is giving England’s Regency period (circa 1813) an entirely new look. True, Miss Austen had previously inspired stacks of so-called “Regency Romances” (featuring frocks that look like nightgowns, and lots of steamy sex), but those insipid novels are easily overlooked. Bridgerton, though, commands attention, because of its sumptuous attention to detail, its gorgeous leading man and lady, and the acid tongue of (yes!) Julie Andrews as the never-seen scandalmonger, Lady Whistledown.

Some of Bridgerton’s historical anachronisms are clearly deliberate. Most obvious (and, I’m sure, most pleasing to series producer Shonda Rimes) is the fact that these Britishers live in a colorblind society in which Black characters belong to the nobility as well as the servant class, with no one batting an eye at the horrors of interracial mixing. I’m told the color palette of the series’ Regency costumes has been tweaked for effect: it’s hard to imagine a real-life dowager, like the ambitious Baroness Featherington, pairing a bright green gown with fuchsia gloves. I’m also skeptical about the Duke of Hastings’ very 21st-century stubble-beard look. Then there are the women’s towering hairstyles, worn mostly by unappealing characters, that I suspect are intended to amuse, not to convince. (And did louche types really smoke cigarettes in 1813?)

Of course in an entertainment like this one, everyone has sex on the brain. It’s surely historically accurate to say that in Regency England proper young ladies were kept ignorant of the facts of life. (One young man scoffs to his mystified sister, “Haven’t you ever been to a farm?”) But of course part of the fun of dramas like this one is to show our modern attitudes intruding upon period conventions. So the spirited but innocent Daphne Bridgerton is encouraged by her future husband to explore masturbation, with stunning success. (This at the same time that an unchaperoned walk between a young lady and gentleman might be cause for a duel.) And of course the machinations to marry off a secretly pregnant young woman become moot when modern-style tolerance enters the picture.

No question: this series was created with a female audience in mind. True, Daphne (played by Phoebe Dynevor) is lovely, in an ethereal way. She has a willowy form that empire gowns can only enhance, plus a face with a knack for looking tremulous, either in moments of bliss or sorrow. But I suspect most viewers particularly cotton to the macho charms of Regé-Jean Page as Simon Basset, the angst-y but noble Duke of Hastings. Once these two discover the joys of married life, the camera can’t get enough of his shirt-sheddings and drawer-droppings. Of course his moral scruples about their future life together make very little sense in context, nor does her sudden discovery of what’s lacking from the connubial gyrations that take place in seemingly every nooks and cranny of the family estate. (I’m no prude, but I’m still scratching my head over what leads her to figure out—in a flash—what he’s been withholding all this time.)

Obviously, plotting is not Bridgerton’s strong suit. Miss Marina Thompson’s scandalous pregnancy remains invisible (even in those diaphanous gowns) for what seems many months, while other events fly by in a flash. A big reveal in the final episode, one that settles what has been a major question from the start, makes absolutely no sense. Which leads me to wonder about season 2. Now that the leading characters are finally happy, what else is there to amuse us?

February 12, 2021

A Cautionary Tale for Valentine’s Day: “Promising Young Woman”

Promising Young Woman takes on the old movie formula of an attractive young female who suffers at the hands of men, then goes out to seek grim revenge. I’ve worked on heaps of genre movies beginning with that premise, which starts with innocence violated and ends with bloody (though hardly unjustified) retribution. See, for instance, Roger Corman’s Jackson County Jail as well as the Slumber Party Massacre flicks. Promising Young Woman (written and directed by the talented Emerald Fennell) doesn’t exactly upend the genre conventions. But it explores them, and eventually turns them not upside down but sideways.

The leading character in Promising Young Woman is fiercely played by the infinitely flexible Carey Mulligan, whom I recently saw as a wise, sad middle-aged British widow in the absorbing British production, Dig. In that film, which dealt with the unearthing of the Anglo-Saxon treasure trove at Sutton Hoo, she was passionate about archaeology and her young son. In Promising Young Woman, by contrast, she plays a much younger American (barely 30) who has put her intellectual savvy to work in trying to right a wrong by any means necessary. It’s probably telling that the character’s name is Cassie, short for Cassandra. In Greek legend, Cassandra was the Trojan priestess endowed with the ability to prophesy the future. It’s less a gift than a curse, because no one believes her. I don’t want to stretch this point overmuch, but the modern-day Cassie sees things that others dismiss or overlook, and her obsession leads her to act in ways that can’t be predicted.

Promising Young Woman is easily categorized as a revenge drama, but some critics prefer seeing it as a dark comedy. The confusion makes sense, because the tone of the movie fluctuates in fascinating ways, helped by a musical score that introduces perky pop tunes (“It’s Raining Men”) as well as, at a key moment, a solemn romantic ballad from The King and I, one that deeply underscores the story’s entrenched ironies. There’s one extended sequence in a pharmacy that’s so lovably giddy that it reminds me of a similar scene in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, in which Holly and Paul steal animal masks from a novelty store.But finally our amusement rings hollow, reminding us that one of this tale’s underlying points involves how young people laugh off matters that are (or should be) deeply troubling.

Amazing how in this film, as in life, a serious past transgression is shrugged off by many of those involved with the excuse “We were so young.” Which couldn’t help reminding me of the confirmation hearing for a certain U.S. Supreme Court Justice. Young adults, even smart ones, are capable of behavior that’s absolutely heinous. The wrong-doers may be able to shrug it off, abetted by sympathetic administrators who would very much rather not make trouble, but victims—as well as some of those who are victim-adjacent—cannot so easily erase the misdeed from their minds and hearts. Promising Young Woman is, at base, the tale of someone who can’t forgive and forget, and whose whole life becomes wrapped up in exacting payback. What makes Cassie so interesting is that she’s not, fundamentally, either a victim or a villain, but rather a combination of the two. She has a generous side, and can be, under the right circumstances, wonderfully sardonically funny. And sexy, and even a trifle tender. Still, when push comes to shove, there are lines she will never let anyone cross. Carey Mulligan first came to filmgoers’ notice with An Education, and this new film shows to what extremes that education can take her.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers