Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 50

January 5, 2021

Looking Back on “Hester Street” and the talented Joan Micklin Silver

On the first day of a new year that we hope will bring better times, it was sad to read of the passing of a filmmaker who once showed great promise. Joan Micklin Silver, the barrier-breaking director of seven feature films, died on December 31 of vascular dementia. Her best-received film was doubtless 1988’s Crossing Delancey. It featured Amy Irving as a hip, well-educated escapee from New York’s ultra-ethnic Lower East Side: she finds love, despite herself, with the nice young man who owns the local pickle shop. It was Irving’s then-husband, Steven Spielberg, who made the project happen, after studio bosses had resisted it for being too overtly Jewish. Happily, audiences felt otherwise, falling in love with the story’s ethnic charm and with the essential Bubbe character—she’s the one who calls in a matchmaker to improve her granddaughter’s marital choices—played by a veteran of Yiddish theatre, Reizl Bozyk.

Silver’s very first film was even more “ethnic,” which is why Hollywood brass (completely ignoring the industry’s historic Jewish roots) unanimously passed on it. It eventually became a family project, with Silver’s husband, real estate developer Raphael Silver, stepping in to finance, produce, and even help with distribution. Yes, I’m talking about Hester Street, a low-budget 1975 gem based on a story called “Yekl,” by Abraham Cahan. Cahan was a fascinating character. His English-language masterwork, 1917’s The Rise of David Levinsky, reflects something of his own journey from Tsarist Russia to New York City. But today he is mainly remembered as the longtime editor of the Yiddish-language Daily Forward. In an ongoing advice column know as “A Bintel Brief” (“A Bundle of Letters”), he helped recent Jewish arrivals from eastern Europe adapt to American life.

“Yekl,” first published back in 1896, focuses on a recent immigrant, a strapping young fellow, making his way on New York’s Lower East Side. He’s renamed himself Jake, found a job as a presser in a garment factory, and on his free evenings enjoys dances at the local social hall. Though he’s been making time with a vivacious young lady named Mamie, he’s saving up to send for his wife and young son who are still back in the Old Country. When Gitl finally leaves the shtetl to resume her role as Yekl’s spouse, he realizes that she – pious and old-fashioned – can’t hope to measure up to the charmers who’ve learned modern ways in Manhattan. Naturally, the old-world marriage can’t hope to survive, given the temptations of the new.

Silver brilliantly adapts this material to focus less on Jake and more on Gitl, who quickly discovers that her values and her standards (like the pious insistence on keeping her hair covered with a wig) are no longer respected in her new life. She tries hard to adapt to her husband’s ways, but as a just-off-the-boat “greenhorn” she can’t hope to compete with modernized Jewish women like Mamie. What’s fascinating in Silver’s film is the way Gitl evolves, turning a marital crisis into a success story, without losing her own soul along the way. The film has an ending that’s Silver’s loving tribute to the American Jews who’ve come before her, showing a resilience and a gift for adaptability that have paved their way to success American-style.

This small black-and-white film introduces us to a Lower East Side that might have been known by our grandparents. Its cast, headed by a luminous Carol Kane, speaks mostly in Yiddish (with subtitles), so their struggles with the English language make perfect sense. Kane was Oscar-nominated, and the film earned an honored place on the National Film Registry.

January 1, 2021

Cue the Cellos: George Clooney Looks at the Midnight Sky Very Very Sadly

You think you’ve got it bad? Actor/director George Clooney, usually known for his sparkling wit, here tackles a story that begins in the aftermath of a global apocalypse and ends . . . God knows where. It seems he’s a research scientist stuck in the arctic, coping with a fatal illness and an ice-crusted beard. When his colleagues ship out, he’s all alone, giving himself transfusions, then microwaving his pathetic meals and eating them all alone in a large but empty dining hall.

But wait! A small child has somehow been left behind during a group evacuation. She’s largely silent, but her presence brings out George’s long-suppressed paternal instincts. (We know they’re long suppressed, because of the occasional flashbacks in which a young guy who looks nothing like George Clooney tries to ignore a pretty blonde woman who is clearly his mate. She wants a family, but he shrugs her off because, well, a man’s got to do what a man’s got to do. And what a man’s got to do, apparently, is to give his all to the study of science.

It’s possible this plot strand interested Clooney himself because, at 59, he is a fairly recent father. His twins, with wife Amal Alamuddin Clooney, are now 3 ½. In any case, his sometimes playful interactions with little Iris provide most of the film’s very few light moments.

But don’t think for a moment that we spend the entire film in the arctic. No, we keep cutting away to a large and very fancy spacecraft that looks something like what a talented child would put together with Legos. This is the temporary home of five astronauts, nicely assorted in terms of gender and ethnicity. They’re just now returning from a newly-discovered moon of Jupiter, one that (remarkably enough) is completely conducive to human life. So they’re in a good mood, which is enhanced by the discovery that one of the women is newly pregnant by her boyfriend, the mission’s captain. This pregnancy has taken the two of them by total surprise (though they are, you know, scientists, basic biology doesn’t seem to be their strong suit). Still, everyone is jubilant, despite the fact there’s a spot of worry because they can’t seem to rouse anyone on earth through their various communications devices.

Finally, after lots of lugubrious music by the usually capable Alexandre Desplat, Clooney and kid race across the frozen wasteland and find means to connect with the astronauts. His message: Don’t come home. But by this point, bad things are happening in space as well (triggering the film’s #1 grim and ghoulish sequence), and the astronauts’ choices are complicated.

If we’ve been following all of this, we’re expecting a super-grim finale. But of course this is a Hollywood film, one that anticipates uplift. And so in the grand tradition of such recent space epics as Gravity and Interstellar, we take a leap into the mystic. All the plot strands converge in a way that defies logic but is meant to make us feel somehow warm and cozy inside.

Why take The Midnight Sky’s trip out into the universe when there’s so much to explore on our own planet? Yes, I enjoyed The Martian, which stuck closely to the possible, but this conflation of outer space and mysticism is starting to get annoying. (Blame 2001: A Space Odyssey?) Personally, I’d rather be watching a glorious oldie like North by Northwest, or a smart, savvy exploration of life on earth like the new film version of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom. Why bother to fly off to the stars?

December 29, 2020

Romance, 20th and 21st Century Style: "The Shop Around the Corner" and "Sylvie’s Love"

‘Tis the season, they say, for happily ever after. As a respite from the daily Zoom and gloom (thanks, Stacey Freed, for that invaluable turn of phrase), I’ve been seeking out romantic movies with upbeat endings. After watching two of them back to back, I realized what a distance we’ve traveled from 1940 to 2020.

The Shop Around the Corner, adapted from a Hungarian play and filmed with panache by Ernst Lubitsch, is so endearing that its longtime popularity is no surprise. In fact, its basic plotline was borrowed for the Tom Hanks/ Meg Ryan 1998 hit, You’ve Got Mail. You’ve Got Mail introduces two business rivals who loathe each other in person, only to discover they’ve been exchanging romantic messages over the Internet. The Shop Around the Corner of course doesn’t mention AOL. It uses a more traditional form of communication—the letter—to tell the story of two co-workers at a Budapest leather goods shop who spar like cats and dogs in person, not realizing they’ve been anonymously pouring out their souls to one another as pen-pals

The central idea of The Shop Around the Corner involves discovery. The shop is full of secrets, which eventually come to light, for better or for worse. But the two leading characters, played by James Stewart and Margaret Sullavan, are not fundamentally different from whom they appear to be in the workaday world. They’re just hiding their deeper, more sensitive sides from their co-workers, though Stewart gets clued in long before Sullivan, leaving room for some delicious moments in which he knows something she doesn’t. Eventually, of course, love will out, just in time for Christmas.

It’s unfair to compare a classic Lubitsch comedy to a Netflix special, but the new Sylvie’s Love has benefited from major billboard display and a Christmas release. It stars the up-and-coming Tessa Thompson, and its production values are sumptuous. It’s set in Fifties and early-Sixties New York, in and around the world of TV production: everyone wears wonderful clothes (like floor-length evening attire to see a Nancy Wilson concert) and lives very nicely indeed. It all feels like the well-dressed world of Douglas Sirk, except that the central romantic characters are Black, and don’t seem to particularly be suffering because of their ethnicity.

But they suffer: yes, they do. Except, of course, when Sylvie—a clerk in her father’s record store who’s trying to make it in television—lays eyes on Robert, a jazz saxophone ace who comes to the store seeking work. They spar charmingly, until she actually hears him perform and is dazzled. He’s dazzled too, by her frisky cuteness and wit. Since this is a 21stcentury romance, they quickly hop into bed. Which is fine, except for the fact that she’s officially engaged to someone else, an upwardly mobile doctor’s son off doing his military service.

Of course the unthinkable happens, leading to an off-camera wedding, a growing child, and (for Sylvie) the job of her dreams as a TV producer’s assistant with a bright future ahead. All the scenes that might have been interesting in a genuine romantic drama—Sylvie’s complex interaction with her husband, her socially aspiring mother, her daughter—are elided so that we can focus on her welcoming Robert joyously back into her life. I noticed the catchphrases in the film’s trailer: “Forget who you are expected to be. Become who you are meant to be.” It’s not so much about Sophie’s love as Sophie’s self-actualization. Love, that is, of herself and what gives her satisfaction, whoever else it hurts. How very 21st century!

December 25, 2020

Have Yourself a Sweet St. Louie Christmas (An "Unprecedented" Meet Me in St. Louis)

Christmas movies—the old-fashioned kind—tend to be short, sweet, uncomplicated, and sprinkled with music. The Christmas movie that comes to mind right now is Meet Me in St. Louis, the 1944 musical that was one of the first features directed by Vincente Minnelli, and the one that introduced him to his future wife, Judy Garland.

Not that Meet Me in St. Louis is entirely set in the Christmas season. This wholesome story about a large, chaotic family living in a big Victorian house on St. Louis’s Kensington Avenue actually covers an entire year. It’s an eventful year for the Smith family, beginning in the spring 1903 with preparations for the St. Louis World’s Fair and ending with the blaze of electric lights that dazzled fairgoers once the fair opened in April 1904. In the interim, youngsters get lost and get found, and their siblings fall in and out of love. But the most serious plotline involves the announcement by Mr. Smith (the predictably autocratic but slightly addled family patriarch) that a job promotion will send all of them packing for a move to New York City. As Christmas 1903 approaches, seventeen-year-old Esther Smith (Garland) and the others are sadly preparing to leave their comfortable St. Louis life behind. That’s when Garland, with that characteristic quaver in her voice, croons to her sad little sister (Margaret O’Brien) the indelible “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas.”

And what a little sister! I was surprised to see seven-year-old Margaret O’Brien billed in second position, just below Garland, but in many ways this tyke is the one who makes the movie sing. Her character is based on Sally Benson, who grew up to pen the nostalgic New Yorker stories that became the basis for this film. As portrayed in Meet Me in St. Louis, she’s an adorable scamp, one who delights in subjecting her dolls to grizzly fates, then stages funerals for them in the family’s garden. Her comic cakewalk duet with Garland is a delight. She also reminds us of a time when a little kid could safely roam the streets of her neighborhood, without interference from the older generation.

What sent me back to Meet Me in St. Louis (which is charming, but hardly the best movie musical to ever come off the MGM lot) is an “unprecedented” stage production by the Irish Repertory Theatre. This group normally presents dramatic works by Irish and Irish-American playwrights at their cozy playhouse in New York City. When the pandemic hit, they found a way to continue performing, by having the actors play their roles individually, from wherever they were quarantined, against a common specially-designed Zoom backdrop. In a play like Eugene O’Neill’s A Touch of the Poet, it looks as though all the characters are interacting in a tavern (most Irish plays seem to be set in taverns!), even though solo performances have actually been stitched together via clever editing techniques. The IRT’s Meet Me in St. Louis takes this one step further. Company head Charlotte Moore actually directed from St. Louis, where she has been quarantining with family. The actors may all seem to be singing “The Trolley Song” in unison, as they ride a tram toward the World’s Fair site, but in fact they have all recorded themselves separately on their cell phones. Common backgrounds make the illusion of togetherness almost seamless.

Which makes an apt metaphor for this complicated season. In the words of Garland’s big song, “Through the years we all will be together/ If the fates allow . . . so have yourself a merry little Christmas now.”

Here’s actress Melissa Errico’s recounting, in the New York Times, of what it was like to be part of this unique production.

Deepest thanks and holiday wishes to Beth Phillips, who got me hooked on the IRT’s very special work.

December 22, 2020

Christmas in Hollywood?: Bah, Humbug!

The mildly entertaining film version of the recent Broadway hit called The Prom features some of our most glittering talents (Meryl Streep, James Corden, Nicole Kidman) as self-centered thespians who decide to Do Good only when it means they will personally reap some kind of reward. That’s why they jump on the bandwagon for a gay teenager who’s been barred from bringing her lady love to the high school prom, staging what they think will be a big publicity coup to enhance their own sagging box-office appeal. Of course, since The Prom started out as a Broadway musical, it oozes optimism and good-will for all humanity. The stars discover their kinder, gentler selves, leading to a jubilant finale in which everyone (even Kerry Washington as a narrow-minded PTA lady) finds happiness. Sounds like Christmas in June to me.

Hollywood loves redemption movies, especially those set in the Christmas season. Hence the enduring appeal of It’s a Wonderful Life, as well as all those various versions of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, which have starred everyone from Bill Murray to the Muppets We all know that A Christmas Carol ends (after Scrooge has learned to appreciate the warmth and family camaraderie of the holiday season) with plum pudding and a joyful “God bless us everyone.”

Yet Ebenezer Scrooge’s earlier dismissal of the Christmas spirit as “humbug” is what I want to discuss right now. There’s something about celebrity that seems to bring out the worst in those who’ve been blessed with mass media appeal. When I worked in the film industry I saw, along with a lot of very nice people, some who’d definitely let fame and fortune go to their heads. Perhaps it was a weird form of insecurity. But in any case, I watched name-above-the-title celebs demand extra attentions they didn’t deserve. These media monsters expect fealty from those around them, and think nothing of making others suffer if they don’t get their way at every turn.

One such graced the cover of the Hollywood Reporter a few weeks back. There’s a full-colored shattered-looking picture of the star, along with these words: “THE IMPLOSION. It wasn’t just erratic, violent behavior that unmade Johnny Depp. It was his unquenchable thirst for revenge.” Inside are 4 full pages recounting instance after instance of Depp’s disturbingly self-centered behavior. On screen it may be lively and funny, but in real life not so much.

Meanwhile, I can’t resist telling a personal story of how Hollywood’s sense of entitlement infects people other than stars. Decades ago, I was at our local Shubert Theatre, seeing a splashy road-show production of Cats. I was sitting in a house seat, because I’d just written a major piece on this production for the Los Angeles Times. By my side was my three-year-old son, ready and eager for his first big theatre-going experience. Yes, he had a booster chair, and he’d been carefully coached on how to behave.

On the other side of me were two empty seats. They stayed empty until midway through the show when—in the middle of a musical number—a man and his daughter made their way across many laps and plopped down. I knew instantly that He was a well-known local TV personality, one who interviewed bigwigs and gave arts reviews. The child, about 5, didn’t sit quietly in her seat. Instead, she STOOD on daddy’s lap, while keeping up a steady stream of chatter about a production she’d clearly seen before. When I dared to politely reprimand the interlopers, I got an icy glare. The Spirit of Christmas Present? Bah, humbug.

December 18, 2020

Annie and Margaret Dance Their Way into Our Hearts

That's Ann Reinking with bowler hat & legs

That's Ann Reinking with bowler hat & legs

The sudden death of dancer/actress Ann Reinking at age 73 has sent shockwaves through the theatre community. Reinking had her share of film and TV roles, but it was on the Broadway stage that she really made her mark. Reinking will always be associated with Bob Fosse, who directed her in shows like Chicago and made her his longtime leading lady in his private life. After his fatal heart attack in 1987, she became the keeper of his flame, re-choreographing (and starring in) Chicago in the Fosse style and heading a revue launched in his honor. On film, she added terpsichorean grace to the role of Grace Farrell in Annie, and essentially played a version of herself in Fosse’s largely autobiographical All That Jazz.

But in 2019, when it came time to make a miniseries about the dynamics between Fosse and wife Gwen Verdon, Reinking was of course too old to play the girlfriend role. That’s when a young woman named Margaret Qualley entered the picture. Qualley, now 26, is the daughter of the actress Andie MacDowell, who delighted audiences in frothy movies like Green Card, Groundhog Day, and Four Weddings and a Funeral. Qualley herself has had a few showy film roles, notably as the hippie chick who lures Brad Pitt into Manson territory in Tarantino’s 2019 re-writing of history, Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood.

But Qualley started out as a dancer. She’s tall, shapely, and long-limbed, which made her an apt choice to portray the young Reinking in the era when she became Fosse’s #1 (but hardly one and only) love. It’s a role that earned her an Emmy nomination, to go with her Screen Actors Guild nomination as part of the ensemble cast of the Tarantino film.

Qualley’s not short on upcoming projects, including another autobiographical role in My Salinger Year, about a young woman who (while answering J.D. Salinger’s fan mail) aspires to become a writer herself. (Sigourney Weaver plays her literary-agent boss). As of now she’s (somehow, in the age of Covid) filming a miniseries, while she has three more films in pre-production.

Yet what really makes me love her is, of all things, a commercial. But not just any commercial. It was written and shot in 2016 by the ever-inventive Spike Jonze, for a perfume called Kenzo World. How do you tout a perfume without giving anyone a whiff of its fragrance? Well, Jonze and Qualley have found a way that’s original and very funny. Once seen, it’s not something you’ll soon forget.

By the way, Qualley’s Kenzo World commercial was filmed in and around the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, the grandest, most glittery hall in the original Los Angeles County Music Center, used for opera, ballet, and other major events. As an L.A. landmark that was completed in 1964, it has a long connection with movies: it’s been used for many an Oscar ceremony and the massive chandeliers in its lobby were created for The Great Waltz, a long-ago film about the life of Johann Strauss. The Dorothy Chandler (named after its lead fundraiser, the wife of the longtime publisher of the Los Angeles Times) somehow survived the making of the Kenzo World ad, and it’s still standing tall. At least I think it is – it was in fine shape last February, the last time in the pre-Covid era that I was lucky enough to leave my home for a trip to the theatre.

Anyway, here’s Qualley at her wacky best:

December 15, 2020

Who’s Really Got The Right Stuff?

The death of aviator Chuck Yeager last week at age 97 took me by surprise. Frankly, I thought he had died long ago. After all, Yeager’s great era was the 1940s, when the World War II flying ace-turned-test-pilot entered the annals of aviation history by breaking the sound barrier. He continued to fly well into the 1960s, setting records while testing out new designs for the U.S. military and for NASA. Though his lack of a college degree (as well as a strong independent streak) prevented him from entering the astronaut corps, he managed to outlive all seven of the Mercury astronauts who were the first Americans to be sent into space. (The last of them, John Glenn, passed on in 2016 at age 95.)

I learned about Yeager’s contributions while reading The Right Stuff, Tom Wolfe’s 1979 non-fiction account of the Mercury program. Wolfe, a pioneer of so-called New Journalism, dug deep to get at the minute details of the first astronauts’ experiences. But, being a natural-born cynic, Wolfe saw far beyond the heroics, taking a jaded view of seven red-blooded American guys who were being held up to the world as role models. For Wolfe, the true hero was Yeager, whose stoic independence of spirit and complete disregard for celebrity lifted him far beyond the achievements of the astronaut corps, whose chief obligation was to be shot into space as what he called “spam in a can.”

Following on the heels of Wolfe’s book was Philip Kaufman’s 1983 film version of The Right Stuff, which vividly sets up the contrast between Yeager and the Mercury Seven. Yeager, played in an Oscar-nominated performance by playwright-turned-actor Sam Shepard, is tough, taciturn, and ready for anything. Posted out among the Joshua trees of California’s high desert, he rides horses, drinks deep at the local watering hole, and vies playfully with his earthy, beautiful wife (Barbara Hershey). When the call comes to take a newly designed aircraft through the legendary sound barrier, he doesn’t hesitate, even though he’s secretly coping with broken ribs. Nerves of steel . . . he’s got them.

The Mercury guys are brave too, though in many cases far less disciplined. The film follows them through a selection and training process that often seems arbitrary and rather silly. And their own quirks don’t improve our view of them. Alan Shepard (that’s Scott Glenn playing the man who would become the first American in space) has a maddening habit of dropping into Jose Jimenez routines, parroting comedian Bill Dana’s pseudo-Mexican character who was widely popular at the time. (In the film, a Latino medical staffer working with NASA is definitely not amused.) Buddies Gus Grissom (Fred Ward) and Gordon Cooper (Dennis Quaid), both theoretically family men,are all too ready to violate their marriage vows with Cocoa Beach lovelies. Meanwhile, the long-suffering Mercury wives are angling for White House tête-à-têtes with Jackie Kennedy.

The one true Boy Scout in the Mercury ranks is John Glenn, winningly played by Ed Harris. He’s depicted as highly protective of his own wife, who suffers from a debilitating stutter. And he’s not above lecturing the others on how their misbehavior sheds a bad light on the program. But he’s also quick to act as a spokesman when the group feels itself exploited by NASA. No wonder he’s the one Mercury astronaut who ended up in politics.

Kaufman’s film is not without its flaws, like an ending that never seems to end. What I’ll remember is Ed Harris’s smile and Sam Shepard’s ritual request for a stick of Beeman’s gum before each bold flight.

December 11, 2020

The Sounds of Silence in “Sound of Metal”

Movies about people with disabilities tend to lean heavily toward either pathos or uplift. Deafness, for instance, is both tragic and ultimately inspirational in the old 1948 weepy, Johnny Belinda. (It features a deaf-mute heroine who becomes a victim of rape, and later finds herself accused of murder.) A 2019 movie, Sound of Metal, couldn’t be more different. Its central deaf character is not a fragile female but a muscular young man who, as a drummer, is one half of a heavy metal duo. Though he’s a recovering drug addict, he leads a productive life, touring with his romantic partner in a well-equipped RV that doubles as living quarters and a sound studio. An early-morning sequence in which he rustles up breakfast for two, then drops to the floor for a few push-ups, suggests his total contentment with his lot.

But it is not to last. In short order Ruben (an astonishing Riz Ahmed) discovers he’s rapidly losing his hearing. His first thought, after consulting with doctors, is to commit to the $70,000 surgery that will give him cochlear implants, in hopes of restoring his hearing and therefore his career. He is overridden by his lady love, who worries about his mental state and continued sobriety. That’s how he ends up in a peaceful community of deaf addicts, led by a former military man (and former alcoholic) who lives to share with others his respect for the strengths of the deaf community, which forms a world unto itself.

So Ruben, would-be rock god, is suddenly learning American Sign Language, helping out in a school for deaf children, and coming to appreciate the sound of silence. Surprisingly, he seems boyishly happy in these idyllic scenes, but a part of him still yearns for the life that late he led. So he sells off all his assets and undergoes the knife in order to rejoin the hearing world.

I won’t go into what happens next. It seems positive, yes, but not in an obvious way. Let’s just say this film makes room for the deaf community’s view that they are less victims than members of a unique and separate culture, with its own language and outlook. This puts it somewhat in the same league as 1986’s Children of a Lesser God, in which a young deaf woman refuses to accept the need to learn oral speech.

There are certain films that, by their nature, showcase a particular aspect of the filmmaker’s craft. Phantom Thread was of course highly indebted to its superb costume design, and lives-of-the-painters movies like Turner depend heavily on exquisite cinematography that captures the essence of their subjects’ visual style. In Sound of Metal, it is of course sound design that plays an essential role. Early in the film, when Ruben rises early—grinding coffee beans, whipping up a green juice in a blender, grooving to classic jazz on the stereo—we’re distinctly aware of all that he’s hearing. As his ability to hear drops away, we slip in and out of his aural perspective, sometimes registering the sounds of a local drug store and the speech of its employees only as a garbled mass of faint noises and sometimes returning to the normal world of those who are not hearing-impaired. By the time he’s at ease within the nurturing deaf community, the film is completely silent, with subtitles helping those of us not fluent in ASL to approach a world we can’t entirely enter. Which of course makes it a shock to our senses when the implants restore auditory sensations into Ruben’s now-quiet world.

December 8, 2020

Little Boys Blue: “Wildlife” and “Hillbilly Elegy”

There’s nothing especially fresh about stories in which a sensitive young boy watches in quiet dismay as his family disintegrates all around him. Over the years there’ve been films galore on this subject. Like, for instance, 1941’s How Green Was My Valley, in which the family unit is destroyed by social forces and the exploitation of the land. In other films, personal weaknesses outflank social issues as the chief cause of the family’s failure to thrive. I’ve just seen two of these, both made quite recently.

Hillbilly Elegy, based on J.D. Vance’s popular memoir, is the latest release in the long line of work from director Ron Howard. Howard’s sensitivity toward actors is well known, as is his interest in the rural South, stemming from his own childhood portrayal of Opie from Mayberry on TV’s classic The Andy Griffith Show. I have not read Vance’s memoir, which traces his journey from Appalachia to Yale Law, but it apparently has a strong (and controversial) political bent, playing up the forces that contribute to the dark side of the American Dream. In Howard’s hands, though, this is chiefly a multi-generational saga in which loyalty to the family unit is overridden by drug abuse and other horrors. We know that young J.D.’s mother Bev, once a nurse, is hopelessly addicted to opioids, and has even ventured into heroin. We know that as J.D. grows up he’s appalled by her behavior, at the same time that he glorifies his feisty salt-of-the-earth granny, Mamaw. But Mamaw is no saint, particularly when she signals her fury by setting Papaw on fire (!). Frankly, I didn’t see much onscreen motivation for any of this, no particular reason why these people are in this kind of psychic pain.

The screenplay cuts between the young J.D. and his grown-up self, courting a gorgeous Indian-American and trying to make a good impression on big-league Washington law firms. Drawn from a select dinner party (he worries over which fork to use) straight back to the old homestead, he has to confront his mother’s full-blown overdose. That hot mess of a mother is played by Amy Adams (still looking for her first Oscar win). And playing the indomitable Mamaw is a transformed version of Glenn Close (still looking for her first Oscar win). The usually elegant Close now shows off a dumpy figure, frizzy salt-and-pepper hair, a foul mouth, and an ever-present cigarette. Sounds like Oscar bait to me.

A smaller, more delicate project is 2018’s Wildlife, based on a novel by Richard Ford. It was adapted for the screen by actors Paul Dano and Zoe Kazan, with Dano making his directorial debut. The heartland family unit at the center of the drama consists of father Jerry (Jake Gyllenhaal), mother Jeanette (Carey Mulligan, spectacularly good), and son Joe. Jerry seems like a nice guy, but also someone who’s never grown up. Having lost yet another job, he gets it into his head to join a team of firefighters, risking their lives for a pittance to put out a stubborn mountain blaze nearby. In his absence, Jeanette evolves from a sweet, supportive wife into someone determined to make her own way in the world. This includes getting her own job, and then cozying up to a wealthy older man who adores her. Meanwhile poor young Joe stands by, trying desperately to keep his parents’ relationship intact.

It’s a hugely sad but totally convincing portrait of a marriage splitting apart at the seams. Dano and Kazan, who starred together in another of their projects, the hilarious Ruby Sparks, deserve all the kudos they can get.

December 4, 2020

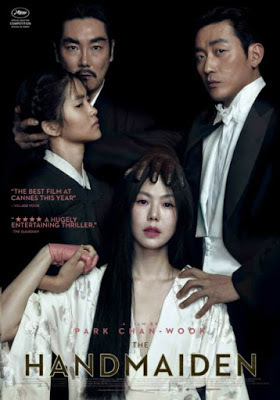

Getting a Handle on “The Handmaiden”

When Parasite started gaining international attention, I was unfamiliar with the work of today’s much-acclaimed South Korean filmmakers. But the bravado style and moral complexity of that twisty thriller (which went on to become the first foreign-language film ever to win Hollywood’s Best Picture Oscar) enthralled me, and I determined to find out more. Decades ago, when I spent a week as a houseguest in Seoul, I was taken to a movie. It was, as I recall, a cheap imitation of an American film. There was a Coca-Cola-style beverage being hustled in the lobby (along with a bad attempt at chocolate candy): the sale of these unappealing items was helped along by an abrupt intermission midway through the flick.

Today, though, many Korean films are exquisitely calibrated works of art. (I’m sure the snacks have improved too.) That’s why I set aside time to watch Chan-Wook Park’s most recent film, The Handmaiden. It’s a period piece, set in the 1930s, when Korea was dominated by a Japanese ruling class, and downtrodden Koreans were expected to have a full command of the Japanese language and customs. That’s why prints for American audiences are subtitled in both languages (yellow fonts for Japanese; white for Korean), and it’s fascinating to see characters switch, sometimes in mid-conversation, from one language to another.

If the language use is fluid in the film, so is identity in general. Many of the characters are trying to pass themselves off as people (and even nationalities) they are not, like the ersatz Japanese count—so aristocratic in his manners—who turns out to be the son of a Korean farmer. Moreover, few characters’ motives are entirely clear. This is brought home to us when, at different points in the film, the same key episodes play out, but with slight variations that change their meaning entirely, depending on whose perspective we are in at the time. In every case, facts blur, deceptions abound, and we in the audience find ourselves rethinking everything we thought we once knew.

As a Roger Corman peon, there was a time I was knee-deep in erotic thrillers, and The Handmaiden is about as erotic as it gets. Bodies are treated frankly, but also with full respect for their beauty. (There’s a sharp contrast here to the bizarre pornographic illustrations—drawn from classic Japanese erotica—that one of the main characters obsessively collects.) But if nudity is one of this film’s staples, so is the respect paid to clothing and adornment. Lady Hideko, the elegant Japanese transplant played by Min-hee Kim, shifts between stylish western flounces and formal kimono, contrasting dramatically with “handmaiden” Sook-Hee’s Korean-style apparel. (I’ve always speculated that the contrast between the tightly-bound Japanese obi and the loosely billowing Korean dress epitomizes the difference between the two cultures.) When garments are switched or removed, it’s often to signal that a radical shift in identity is about to follow. When we see Sook-Hee, now in Japan, suddenly donning sumptuous-looking Japanese brocade, we know something unsettling is about to occur.

One of the pleasures of Parasite was seeing the creative use being made of a hyper-modern Seoul luxury home. The Handmaiden, too, takes vivid advantage of its architectural setting. Much of the film is set in the Korean countryside, where the lascivious Uncle Kouzouki has used his considerable wealth to create an amalgam of a sumptuous Victorian palace and an austere Japanese villa. This hybrid structure in some ways reflects the contradictions of this film, which is both ugly and beautiful, both degrading and uplifting, both minimalist and baroque. But always, always fascinating.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers