Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 54

August 18, 2020

Capering through West Virginia: “Logan Lucky”

Sometimes, especially in the midst of pandemics, girls just wanna have fun. And there’s nothing more fun than a heist movie done right. Logan Lucky falls into that venerable genre of crime capers in which an unlikely team of misfits gathers to pull off – or not quite pull off – an intricate and lucrative job. One of my very favorites is 1964’s Topkapi, directed by American ex-pat Jules Dassin, who had previously helmed the much darker French heist film from 1955, Rififi. The exuberant Topkapi benefits from Technicolor, exotic locales, and a starry international cast (Melina Mercouri, Maximilian Schell, Akim Tamiroff, Robert Morley, and the wonderful Peter Ustinov, who won an Oscar for his role as a nebbishy fallguy.) The action involves an elaborate plan to steal a priceless emerald-encrusted dagger from the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul. Do the crooks get away with it? Well, a little bird has told me what happens next.

Sometimes, especially in the midst of pandemics, girls just wanna have fun. And there’s nothing more fun than a heist movie done right. Logan Lucky falls into that venerable genre of crime capers in which an unlikely team of misfits gathers to pull off – or not quite pull off – an intricate and lucrative job. One of my very favorites is 1964’s Topkapi, directed by American ex-pat Jules Dassin, who had previously helmed the much darker French heist film from 1955, Rififi. The exuberant Topkapi benefits from Technicolor, exotic locales, and a starry international cast (Melina Mercouri, Maximilian Schell, Akim Tamiroff, Robert Morley, and the wonderful Peter Ustinov, who won an Oscar for his role as a nebbishy fallguy.) The action involves an elaborate plan to steal a priceless emerald-encrusted dagger from the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul. Do the crooks get away with it? Well, a little bird has told me what happens next. Two years after Topkapi, I fell hard for a delectable trifle called How to Steal a Million. It’s got Paris, Audrey Hepburn at her most winsome, and Peter O’Toole as his most dashing, so how could I not be charmed? Here’s one caper film where we don’t have to worry at all about suspending moral judgment, because the object being stolen – a small sculpture known as the Cellini Venus – is actually something that belongs to the thieves in the first place. (Don’t ask!) It’s a romantic comedy with a twist of lemon, and what could be more fun than that?

I’m also a fan of an L.A.-centric heist film, 2003’s The Italian Job, in which a large contingent of Hollywood names (Mark Wahlberg, Charlize Theron, Donald Sutherland) co-star with a valiant little Mini-Cooper. The underground, underappreciated Los Angeles Metro shows up in a supporting role, and a good time is had by all. (From all reports, this is a much better film than the 1969 British original.) Speaking of updates, the original 1960 Ocean’s Eleven, featuring hijinks by Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack, was far eclipsed by Steven Soderbergh’s 2001 version, starring George Clooney and a host of other A-listers (Brad Pitt, Matt Damon, Don Cheadle, Elliott Gould, the late Carl Reiner). This Las Vegas casino-heist film proved so popular that it spawned two sequels and then a female spin-off, Ocean’s 8, with Sandra Bullock as Clooney’s sister and the new leader of the pack.

Though Soderbergh claimed in 2013 to have retired from Hollywood, he returned in 2017 with Logan Lucky, about a blue-collar caper which has been called (even within the script itself) Ocean’s 7-Eleven. (The wholly unknown screenwriter may in fact be Soderbergh’s wife, Jules Asner, writing under a pseudonym.) Here the milieu is far from Las Vegas glitz: we’re in West Virginia, a place of beauty (see John Denver’s “Country Roads,” which plays a key role in the plot), but also a land of poverty and desperation. Also, of course, NASCAR. A motley crew played by Channing Tatum, Adam Driver, a slumming Daniel Craig, and two other doofuses figure out an audacious, sometimes downright hilarious, way of ripping off the proceeds of the local race track in order to re-make their down-at-the-heels lives. Also figuring into the plot: cockroaches, gummy bears, a children’s beauty pageant, and a prosthetic arm. The very indie film was shot in a mere 36 days (which puts it nearly in Roger Corman territory): perhaps that’s why hillbilly accents are every which way and some plot elements never quite gel. But if Logan Lucky lacks logic, it certainly has heart—and good cheer. So I’ll cheer: Hooray!

August 14, 2020

"Dolmedes is My Name": Eddie Murphy and Spike Lee

Last year, when the world was still young and full of possibility, Eddie Murphy starred in a flashy but unlikely comedy called Dolemite is My Name. Who knew? I’m hardly in the demographic that remembered the real-life Rudy Ray Moore: the film taught me that he was a comedy and rap pioneer who in the 1970s used the persona of a folk hero loved by the Black community to entertain audiences tickled by outrageous language and even more outrageous behavior.

Last year, when the world was still young and full of possibility, Eddie Murphy starred in a flashy but unlikely comedy called Dolemite is My Name. Who knew? I’m hardly in the demographic that remembered the real-life Rudy Ray Moore: the film taught me that he was a comedy and rap pioneer who in the 1970s used the persona of a folk hero loved by the Black community to entertain audiences tickled by outrageous language and even more outrageous behavior. The part of the film I adored shows Moore, turned down by every major studio, making his own Dolemite movie on his own dime, with a little help from his friends. These include a minor-league Black actor (D’urville Martin) coming aboard on the promise that he can direct, as well as a gaggle of UCLA film students thrilled to be working on a real-life commercial production. It’s supposed to be a Blaxploitation flick with plenty of sex and kung-fu action: the fact that none of the cast and crew know what they’re doing makes for plenty of laughs. I laughed too: after all, I’ve been there.

In the early 1970s, during my New World Pictures days, I worked on such vintage Blaxploitation staples as TNT Jackson. And I remember the excitement when my boss Roger Corman’s brother Gene was shooting a local production called Darktown Strutters. It was the talk of the office when a bank robbery scene was staged on the streets of Hollywood. In the interest of saving money (always a high priority in low-budget filmmaking), no rent-a-cops had been engaged to block off the city streets. So when the robbers emerged from the bank and jumped into their waiting get-away car, passersby naturally assumed that this was the real thing. Other drivers panicked leading to a for-real car crash. Needless to say, the cameras kept on rolling, providing lots of useful action footage. Such is life when filmmaking newbies shoot on a down-&-dirty Roger Corman-type budget.

A Dolemite-inspired character shows up in one of Spike Lee’s more recent endeavors, the loud and outrageous Chi-Raq (2015). Here Lee, in his usual eclectic fashion, addresses the issue of Black-on-Black street crime by taking a page from Aristophanes’ ancient Greek comedy, Lysistrata. In Aristophanes’ audacious 5th century BC play, women put a stop to the Peloponnesian War by denying their husbands sex until the bloodshed ends. Lee borrows something of the Greek comic master’s plot as well as his audacious spirit: his tale of modern-day Chicago (known by some as Chi-Raq in recognition of its bloody streets) includes a spate of bawdy talk, unlikely musical interludes, and high-decibel rap battles. Our guide through this netherworld is the ultra-cool Samuel L. Jackson as Dolmedes, who functions as the story’s narrator or (in the ancient Greek sense) chorus. Like the rest of the characters, he tends to speak in rhyme, and his language is hardly PG-13.

Lee, never shy about taking on artistic challenges, balances the tomfoolery with moments of genuine poignancy, encompassing the fate of children killed by stray bullets in the Chicago streets. (Angela Bassett and Jennifer Hudson nicely take on the role of bereaved mothers.) There’s also (surprising in a film by Lee) a good-guy white Catholic priest played by John Cusack. The wildly disparate elements of the story, and its radical tonal shifts, hardly help viewers like me. I grant I’m not the target audience, but I’m not sure just who is. It’s gutsy to use an ancient comedy to address a contemporary problem, but Lee’s experiment can be described by a classical Greek word: Chaos.

August 11, 2020

Lying at the Feet of a Good Liar

I don’t mean to brag (yeah, right!), but I once shared the stage with Sir Ian McKellen. Touring the world in a one-man show, McKellen stopped off in L.A. for a stint at the Westwood Playhouse. The evening was called Acting Shakespeare, and he alternately emoted and conversed with the audience, discoursing on how he prepared himself for the great Shakespearean roles that crowned his brilliant stage career. At one point, he announced that he needed volunteers from the audience, the more the better. As we all turned shy, he reminded us that this was probably our only chance to serve as his acting partners. Surely the bragging rights were worth a little embarrassment? That broke the ice: about twenty of us slowly got to our feet and came down the aisles to mount the stage.

I don’t mean to brag (yeah, right!), but I once shared the stage with Sir Ian McKellen. Touring the world in a one-man show, McKellen stopped off in L.A. for a stint at the Westwood Playhouse. The evening was called Acting Shakespeare, and he alternately emoted and conversed with the audience, discoursing on how he prepared himself for the great Shakespearean roles that crowned his brilliant stage career. At one point, he announced that he needed volunteers from the audience, the more the better. As we all turned shy, he reminded us that this was probably our only chance to serve as his acting partners. Surely the bragging rights were worth a little embarrassment? That broke the ice: about twenty of us slowly got to our feet and came down the aisles to mount the stage. McKellen proceeded to have the curtain lowered, cutting off the view of those still in their seats, and then privately told us what this was all about. He was going to do one of Shakespeare’s great battlefield orations, in which a king (was it a Richard or a Henry?) laments the death and destruction he’s just witnessed We, his newly minted entourage, would stand quietly behind him. A certain line would be our cue. When it came, we were all to slump to the floor, dead. And there we’d lie, not moving, not breathing if we could help it, until his powerful oration came to an end.

Though McKellen is renowned for his stage work, he’s also done his share of films. And what an eclectic lot they are! He’s played classical roles, of course, and nabbed a well-deserved Oscar nomination for portraying openly-gay Hollywood director James Whale in 1998’s Gods and Monsters. (McKellen has long an “out” actor who takes pride in his activism on behalf of gender equality.) on Another Oscar nod honored his portrayal of Gandalf in Lord of the Rings. He was featured as Magneto in the X-Men films, played the alarm clock, Cogsworth, in Disney’s live-action Beauty and the Beast, and was Gus the Theatre Cat in the much-lambasted film version of the stage perennial, Cats.

Last year, at the impressive age of 80, he took a major role that didn’t require fancy makeup. The film was The Good Liar, a thriller based on a popular novel, in which he played opposite the redoubtable Helen Mirren. Though McKellen’s character, Roy Courtnay, does not resort to screen-worthy disguises to hide his true identity, he’s in fact a nefarious con man masquerading as a pleasant but feeble old codger. Feigning a bad leg, he insinuates himself into the home (and apparently the heart) of a retired college professor named Betty. She seems surprisingly naïve, but is she? His goal is to siphon off all of her money. Her goal – well, it’s complicated, but we sense from the start that any character played by Mirren is no pushover. Best-known by moviegoers for her Oscar-winning portrayal of Elizabeth II in The Queen, she gravitates toward parts that suggest a gracious but steely intelligence.

The Good Liar’s big reveal, which follows an apparently light-hearted trip à deux to Berlin, might read well on the page. But the long flashback that explains a previously concealed past history comes off on screen as highly unlikely, leaving viewers like me to feel manipulated. Which is perhaps why this film, despite its starry pedigree, did not wow ticket-buyers. Still, watching two of England’s greatest thespians battle for supremacy is definitely a treat. And if acting is simply an elaborate form of lying, play on!

August 7, 2020

Soaring and Crashing with The Great Santini

War is hell, but perhaps there are some for whom peace is worse. One such is Lt Colonel Wilbur “Bull” Meechum of the U.S. Marine Corps in the Pat Conroy novel that became a 1978 film. Meechum, who thrives on being in command (of his fighter jet, his men, all the members of his family) enjoys dubbing himself The Great Santini when he’s pulled off some flashy stunt. He’s played with panache by the always impressive Robert Duvall, who was Oscar-nominated for this role three years before he took home the statuette for Tender Mercies. A supporting actor nomination went to young Michael O’Keefe, for playing Meechum’s oldest son.

War is hell, but perhaps there are some for whom peace is worse. One such is Lt Colonel Wilbur “Bull” Meechum of the U.S. Marine Corps in the Pat Conroy novel that became a 1978 film. Meechum, who thrives on being in command (of his fighter jet, his men, all the members of his family) enjoys dubbing himself The Great Santini when he’s pulled off some flashy stunt. He’s played with panache by the always impressive Robert Duvall, who was Oscar-nominated for this role three years before he took home the statuette for Tender Mercies. A supporting actor nomination went to young Michael O’Keefe, for playing Meechum’s oldest son. O’Keefe, whose role is that of a sensitive high school senior with a talent for basketball, is in fact the eldest of seven children from a devout Irish Catholic household. Which made him an ideal choice to play Ben, the eldest of four kids reined in by their mother’s gentle devotion as well as their father’s strict, elaborate codes of conduct. The Great Santini treats his wife and children like members of his squadron, issuing commands, barking out reprimands, sometimes engaging in horseplay but always with the sense that he’s the one in charge. In an especially dramatic segment, a friendly one-on-one backyard basketball game between father and son turns into a violent confrontation when Meechum can’t bear being defeated by his own kid. The ramifications of this moment are huge, resulting in a disaster when Ben takes the court for real as part of his high school team.

Though the film has other plot strands, its heart is in these fraught father/son clashes. That’s doubtless because Pat Conroy, the author of the original novel, was writing close to the bone, about his own memories as the eldest son of a Marine flyboy father whose commitment to military discipline, as well as military hijinks, threatened to tear a family apart. The word is that when the novel was published in 1976, other Conroys took umbrage at this spilling of family secrets, like Donald Conroy’s violent streak and his excessive drinking. Some in the family apparently picketed book signings, passing out leaflets urging would-be patrons to avoid buying Pat’s novel. Conroy has said that in later years his father would, with apparent good humor, autograph copies as follows: "That boy of mine sure has a vivid imagination. Ol' lovable, likable Col. Don Conroy, USMC (Ret.), the Great Santini." Happily, I’ve heard that in later years—partly as a response to the novel—the elder Conroy became a kinder and gentler man.

I was delighted to spot in the cast of The Great Santini (along with the always luminous Blythe Danner as Meechum’s Southern-born wife) an old Roger Corman chum of mine, Stan Shaw. Stan began his film career in 1974 with Corman blaxploitation flicks like Truck Turner and TNT Jackson. I knew him from the latter, in which—as the male lead--he enjoys both torrid sex scenes and violent kung fu clashes with the bodacious Jeanne Bell. When we worked together on publicity releases, I was impressed at Stan’s far-ranging artistic ambitions. Not content simply to be the hero or the bad guy, he aspired to do it all, even if this meant playing a baby, playing a dog. Still working, he’s had a long and varied career, mostly in television, small roles, and small films. In The Great Santini he plays Ben’s unlikely buddy, a sweet and simple soul who loves nature but falls prey to a white bully in one of the pivotal moments of Ben’s impressionable young life.

August 4, 2020

Wilford Brimley: Farewell to an Old Guy Who Really Felt His Oats

Crusty Wilford Brimley, he of the walrus mustache and the passion for Quaker Oatmeal, has left us at the ripe old age of 85. Curiously, the former soldier and ranch hand made his mark on Hollywood by playing men much older than his actual years. He was only 51 when he co-starred in Ron Howard’s Cocoon with such Hollywood veterans as Don Ameche (age 77), Hume Cronyn (age 74), and Jack Gilford (age 77). His wife was played by sixty-year-old Maureen Stapleton, and the legendary stage and screen star Jessica Tandy (age 76) was also featured in the cast. (In 1984 I was privileged to interview Tandy and her longtime spouse, Cronyn, backstage before a production of Foxfire. But that’s a story for another day.)

Cocoon, for those too young to remember, concerns a group of oldsters living in a Florida retirement community. Plagued by health challenges and a loss of youthful vigor, they are not much enjoying their so-called golden years. Then the unthinkable happens: the elderly folks, somehow rejuvenated by the magical life-force in a neighbor’s swimming pool, are visited by aliens who invite them to sail to a distant planet where they can live forever. It is not an easy parting: most of them will be leaving behind friends and family as they sail off into the unknown. A few (Gilford’s character among them) choose to stay where they are: as he puts it in a poignant speech, “This is my home. It’s where I belong.”

Ron Howard, in 1985 still early in his directing career, was so anxious about guiding the performances of legendary thespians that he was plagued by bizarre dreams: “I’m on a set, and something is just not clicking. I’m scrambling around, trying to make it happen, but I don’t really have the answers.” When he makes a tentative suggestion, everyone on the set turns to him and yells, “You’ve got to be kidding! That’s the stupidest thing we’ve ever heard.” Then, in his dream, the thoroughly red-faced Howard lurches into a desperate song-and-dance routine. In fact, the acting veterans liked and respected the thirty-one-year-old Howard. Which didn’t mean they refrained from pushing back when necessary. In that swimming pool scene, Brimley, Cronyn, and Ameche are required to cavort like youngsters, doing exuberant flips, dives, and cannoballs. Because of the age of his performers, Howard hired doubles to execute these stunts, then discovered the three actors were miffed: “They wanted to do it themselves. And they did. They really taught me that you can’t generalize about what people can, or cannot, do because of age.”

Howard was also surprised to learn that each senior member of his company had a different approach, which he needed to blend into a unified whole. Of the four cronies whose actions dominate much of the film, Hume Cronyn devoted much mental energy to analyzing his role, while Jack Gilford called on the skills of a trained vaudevillian. The dapper Don Ameche, whose nimble (and Oscar-winning) breakdancing scene is one of the film’s highlights, turned out to be an old-school Hollywood film actor who begged Howard to give him precise direction. As for curmudgeonly Wilford Brimley, he was happiest when going his own way. A prime example is the fishing scene, in which his character breaks the news to his beloved grandson that he’s leaving for outer space. With Howard’s blessings, Brimley discarded the scripted lines and improvised a simple but deeply moving farewell. Says Howard, “It is one of the scenes I've always been proudest of, and I had virtually nothing to do with it.”

Some of the material from this post was taken from my 2003 biography, “Ron Howard: From Mayberry to the Moon . . . and Beyond,” which has surprised me by becoming, during the pandemic, an Amazon bestseller in its Kindle edition. Up-and-coming: an audio version from Tantor. (Fingers crossed.)

The Loneliness of the Elderly English Thespian

One of the things I love about great actors is how malleable they are. Watching the young Tom Courtenay in his breakout film, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962), I was thoroughly convinced he was a working-class kid with a chip on his shoulder. This film, directed by Tony Richardson, is a landmark of the so-called British New Wave, a period (roughly 1959-1963) of of grimly ironic, loosely-structured independent flicks set among Britain’s working class. Adapted by Alan Sillitoe from his own acclaimed short story, it shifts between the central character’s unexpected talent for long-distance running and his recollections of the shabby surroundings and shady people that have led him to a stint in a borstal, or detention center for underaged boys. His final act of defiance is vividly shown to have sprung forth from the resentments of an underclass against the snooty expectations of their social betters.

One of the things I love about great actors is how malleable they are. Watching the young Tom Courtenay in his breakout film, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962), I was thoroughly convinced he was a working-class kid with a chip on his shoulder. This film, directed by Tony Richardson, is a landmark of the so-called British New Wave, a period (roughly 1959-1963) of of grimly ironic, loosely-structured independent flicks set among Britain’s working class. Adapted by Alan Sillitoe from his own acclaimed short story, it shifts between the central character’s unexpected talent for long-distance running and his recollections of the shabby surroundings and shady people that have led him to a stint in a borstal, or detention center for underaged boys. His final act of defiance is vividly shown to have sprung forth from the resentments of an underclass against the snooty expectations of their social betters. That role put Courtenay on the map. Soon after, he got even more attention for playing another downtrodden Brit, this one with a crazily vivid imagination, in Billy Liar. Fortunately, his later film and stage work allowed him to branch out, and he was Oscar-nominated as a Russian revolutionary in Doctor Zhivago. About two decades later, in 1983, Courtenay transferred one of his all-time best stage roles to the screen. His character, Norman, in Ronald Harwood’s The Dresser couldn’t have been more different from The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner’s feckless Colin Smith. The Dresser is set in the English provinces, at the height of World War II, when blackouts and German bombs are everywhere, and Brits are desperate for public entertainment. The central characters are all part of a small acting troupe touring the hinterlands, bringing Shakespearean classics to the masses. They’re a motley lot, but their star (always referred to as “Sir”) is beloved by audiences for his bombastic talents and his longevity. Never the easiest of men to please, he’s vain and dictatorial—and all too aware that his lease on life may soon expire. Courtenay plays his dresser and all-purpose assistant, who knows how to wrangle the old man into doing what needs to be done, whether through flattery, through bullying, through bribery, or through desperate pleading.

Norman has no desire to actually be an actor (he’s terrified when he has to go onstage and make an announcement), but his work as Sir’s round-the-clock factotum is itself the most demanding of acting roles. No accident that the play being performed through much of the film is King Lear, with Sir as the ageing monarch raging against the dying of the light. For all that he performs his role offstage, Norman can be pegged as Lear’s Fool: lowly, sometimes ridiculous (and, frankly, effeminate), but blessed or cursed with a shrewd understanding of his master.

Harwood, the author of The Dresser, based the play on his memories of touring for five years as the dresser of Shakespearean actor-manager Sir Donald Wolfit. Wolfit was advanced in years at the time, but not (like the character of Sir) at death’s door. Having just seen Albert Finney in the role, I was surprised to discover that this big, limp sack of a man—clearly failing, but with some residual grandeur—was in fact in his mid-forties, just twenty years past his boyishly roguish lead role in Tom Jones. (I also learned that Courtenay’s screen role in Billy Liar was introduced on stage by none other than Albert Finney: the two are barely a year apart in age.)

That’s why I love actors: they’re always capable of surprises.

I've just discovered there's a 2015 TV version of The Dresser, starring British treasures Ian McKellan and Anthony Hopkins. How wonderful to find such rich parts for men of advanced age! Here's a trailer for that production, slightly less bombastic than the 1983 trailer above.

July 31, 2020

The Loneliness of the Elderly English Thespian

One of the things I love about great actors is how malleable they are. Watching the young Tom Courtenay in his breakout film, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962), I was thoroughly convinced he was a working-class kid with a chip on his shoulder. This film, directed by Tony Richardson, is a landmark of the so-called British New Wave, a period (roughly 1959-1963) of of grimly ironic, loosely-structured independent flicks set among Britain’s working class. Adapted by Alan Sillitoe from his own acclaimed short story, it shifts between the central character’s unexpected talent for long-distance running and his recollections of the shabby surroundings and shady people that have led him to a stint in a borstal, or detention center for underaged boys. His final act of defiance is vividly shown to have sprung forth from the resentments of an underclass against the snooty expectations of their social betters.

That role put Courtenay on the map. Soon after, he got even more attention for playing another downtrodden Brit, this one with a crazily vivid imagination, in Billy Liar. Fortunately, his later film and stage work allowed him to branch out, and he was Oscar-nominated as a Russian revolutionary in Doctor Zhivago. About two decades later, in 1983, Courtenay transferred one of his all-time best stage roles to the screen. His character, Norman, in Ronald Harwood’s The Dresser couldn’t have been more different from The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner’s feckless Colin Smith. The Dresser is set in the English provinces, at the height of World War II, when blackouts and German bombs are everywhere, and Brits are desperate for public entertainment. The central characters are all part of a small acting troupe touring the hinterlands, bringing Shakespearean classics to the masses. They’re a motley lot, but their star (always referred to as “Sir”) is beloved by audiences for his bombastic talents and his longevity. Never the easiest of men to please, he’s vain and dictatorial—and all too aware that his lease on life may soon expire. Courtenay plays his dresser and all-purpose assistant, who knows how to wrangle the old man into doing what needs to be done, whether through flattery, through bullying, through bribery, or through desperate pleading.

Norman has no desire to actually be an actor (he’s terrified when he has to go onstage and make an announcement), but his work as Sir’s round-the-clock factotum is itself the most demanding of acting roles. No accident that the play being performed through much of the film is King Lear, with Sir as the ageing monarch raging against the dying of the light. For all that he performs his role offstage, Norman can be pegged as Lear’s Fool: lowly, sometimes ridiculous (and, frankly, effeminate), but blessed or cursed with a shrewd understanding of his master.

Harwood, the author of The Dresser, based the play on his memories of touring for five years as the dresser of Shakespearean actor-manager Sir Donald Wolfit. Wolfit was advanced in years at the time, but not (like the character of Sir) at death’s door. Having just seen Albert Finney in the role, I was surprised to discover that this big, limp sack of a man—clearly failing, but with some residual grandeur—was in fact in his mid-forties, just twenty years past his boyishly roguish lead role in Tom Jones. (I also learned that Courtenay’s screen role in Billy Liar was introduced on stage by none other than Albert Finney: the two are barely a year apart in age.)

That’s why I love actors: they’re always capable of surprises.

I've just discovered there's a 2015 TV version of The Dresser, starring British treasures Ian McKellan and Anthony Hopkins. How wonderful to find such rich parts for men of advanced age! Here's a trailer for that production, slightly less bombastic than the 1983 trailer above.

July 28, 2020

Shampoo: Pandemic Porn at the Beauty Salon

Blame it on the fact that I need a haircut and can’t get one right now, due to the new COVID-related mandates in Los Angeles County. But last night I got a hankering to watch Shampoo, the 1975 film in which Warren Beatty—as a Beverly Hills hairstylist—uses a blow-dryer as a tool of seduction. Frankly, those scenes of soignée women buzzing around Beatty at a hair salon come across to me now as pandemic porn. And I can see the appeal of Beatty’s tousle-locked George, who makes house calls and has never heard of social-distancing. On his lips, the words, “I’d like to do your hair” sound like a love-call. Or (to be frank) a booty call.

Shampoo comes from Hollywood royalty, produced by Beatty, directed by Hal Ashby (The Last Detail, Coming Home), co-written by Beatty and Robert Towne (Chinatown). It plays like a poisoned Valentine to L.A., made by someone who hates the place while also being infatuated by it. The film certainly contains moments of wit, as when the cuckolded Lester (Jack Warden) nearly barges in on George in flagrante, but (conveniently certain that all male hairdressers are gay) sees a blow-out instead of a blow-job. And there’s a sharply etched portrait by seventeen-year-old Carrie Fisher in her film debut as the precocious daughter of one of George’s many flames, played by the Oscar-winning Lee Grant. (Others in George’s harem include the very miniskirted Julie Christie and Goldie Hawn, all golden locks and gangly limbs. The film was made in the era when Beatty, coming off Bonnie and Clyde, was still a Hollywood heartthrob; he and Christie, who were romantically linked in real life, had previously starred together in Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller.)

Shampoo tries to rise to social significance via covert references to the politics of the era. The action begins on the eve of the 1968 election of President Richard Nixon and Vice-President Spiro Agnew. No one in the film expresses a heartfelt political opinion, but some key scenes take place at a Republican election-night fundraising soiree, so the implications seem clear. There are also frequent reminders, via radio and television bulletins, that the Vietnam War is raging all the while that oblivious Angelenos party on.

Frankly, I didn’t find any of the above terribly meaningful, though others may see in Shampoo an apt skewering of an era of self-indulgence, fostered by what a John Updike character once called “the post-pill paradise.” I will admit that the film looks fabulous, showing off both the gorgeous curves of the female characters and the glorious curves of the roadways on which George’s motorbike whizzes as he moves from Downtown Beverly Hills to Bel-Air to the Valley in pursuit of sexual gratification. Richard Sylbert, who had so successfully captured the look of L.A. in The Graduate (not to mention Chinatown) picked up another Oscar nomination for art-directing all the varieties of chic décor in the characters’ drop-dead-gorgeous houses. Another parallel to The Graduate is that this film too advertises a Paul Simon score. Alas, though a very entertaining trailer for Shampoo uses Simon’s “59th Street Bridge Song” (aka “Feelin’ Groovy”) to set the mood, the film itself makes little memorable use of Simon. I did like, though, the number we hear under the closing credits, the Beach Boys’ wistful “Wouldn’t It Be Nice?” Their lyrics, suggesting a dream of a more mature but still romantic future, ideally represent the boy-man Beatty plays, with his fantasy of a better life to come. Wouldn’t it be pretty to think so?

July 24, 2020

Rising While Seated: The Surprising Career of Nell Blaine

It’s an old Hollywood cliché: someone is felled by a tragic illness or accident, but still rises (literally or figuratively) to have a satisfying life. I’m thinking of such schmaltzy films as 1959’s semi-biographical The Five Pennies, in which the little daughter of bandleader Red Nichols (Danny Kaye). contracts polio and loses the use of her legs. Her disability throws her dad into such despair that he throws his beloved trumpet into San Francisco Bay. Years later she persuades him to resume making music, and at last he’s rewarded by seeing her discard her cane to dance with him. Something similar happens in Disney’s 1960 Pollyanna. In this screen adaptation of a popular 1913 novel, a hyper-cheerful youngster (Hayley Mills) loses her spunk when her legs are paralyzed in an accident. Happily, she’s helped by loving neighbors to regain her high spirits in time for an operation that will restore her to good health.

In a more realistic vein are several war-related films showing disabled veterans who—though permanently affected by injuries—still find room in their lives for emotional satisfaction. In Coming Home (1978), the soldier played by Oscar-winner Jon Voigt returns from Vietnam a paraplegic, but his bitterness dissipates when he embarks on a passionate affair with a VA hospital volunteer played by Jane Fonda. Born on the Fourth of July, the 1989 film based on Ron Kovic’s autobiography, shows how a Marine sergeant who has returned from Vietnam in a wheelchair finds new purpose in his life through active support of the anti-war movement. In Forrest Gump (1994), Lt. Dan (played by Gary Sinise) recoils from his “cripple” status after losing both legs in a Vietnam ambush, but is helped by Forrest to recover his will to live. By the end of the film, he’s found both wealth and love.

Then there are the multiple versions of Love Affair (also known in its 1957 Cary Grant/Deborah Kerr iteration as An Affair to Remember). Charles Boyer and Irene Dunne had starred in the 1932 Love Affair, which was remade with Annette Bening and Warren Beatty in 1994. All three films showcase a shipboard romance between a man and a woman who have other romantic commitments awaiting them on shore. They vow to reunite months later at the top of the Empire State Building if their love has a chance to move forward, but the woman—seriously injured in a traffic accident—fails to keep the rendezvous. It’s only by happenstance that the man discovers what has kept his beloved from his side. Of course, though she can no longer walk, there’s a happy romantic fadeout.

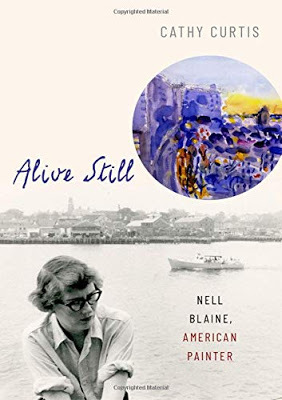

All of which adds perspective to Alive Still, my colleague Cathy Curtis’s well-wrought new biography of 20th century American painter Nell Blaine (1922-1996). In 1959, Blaine, already a rising American artist, saved up to take a dream trip to the island of Mykonos. The Greek landscape and dazzling light enthralled her, but it was there she contracted polio. After surviving a long stint in an iron lung, she recovered enough to resume painting. Alas, her right arm no longer had its prior strength. Nothing daunted, she trained herself to paint left-handed when she worked with oils. For watercolors, she could rely on her right hand, but only by using her left hand for support. Curtis’s book makes clear how very difficult it is to navigate daily New York life from a wheelchair. Staircases? Taxis? Small apartments with tiny bathrooms? But, steadily resisting the urge to ask for public sympathy, Blaine rose to greater artistic heights than ever before. Brava, truly!

July 21, 2020

The Candidate Discovers Plastics

This is an intensely political year, and so I chose to catch up with a 1972 film that American political junkies often reference. At a time when Richard Nixon was winning re--election, The Candidate focused on a fictional California race for the U.S. Senate, one that seemed to reward the value of style over substance, suggesting the evolution of politics into a beauty contest in which the best-looking candidate wins. And they don’t get much better looking than the young Robert Redford, who was the film’s star.

Coincidentally, Redford came close to winning the title role in 1967’s The Graduate, in which “plastics” stood in for all that was crass in the modern world. Plastics in The Graduate was something that recent big-man-on-campus Benjamin Braddock was determined to resist in his adult life. In The Candidate, Redford plays Bill McKay, an idealistic young California activist with cover-boy looks. When the film opens, he has absolutely no use for political game-playing; obviously this is a reaction against his father (Melvyn Douglas), a seasoned political pro who was once the governor of the state. Because the Republican incumbent, Senator Crocker Jarmon, seems to have a lock on the upcoming election, the Democratic party hack played by Peter Boyle only needs to find a patsy to be Jarmon’s token opponent. He persuades Bill to run by pledging he’ll have full independence to state his own views.

But wait! Bill captures the public’s fancy, and soon Boyle’s character is reshaping him into a bland but attractive golden-boy who can steal the Senate seat from the ageing silver fox currently holding the office. It’s made clear, especially in a televised debate scene, that neither of them is going to go beyond platitudes and nice-sounding slogans. At times Bill fights against his makeover (which includes a trendy new haircut and wardrobe), but everyone, including his loving wife, is soon pressuring him to play the game. He reluctantly accepts his father’s involvement, though he cringes at Dad’s proud acknowledgment that he’s become a politician.

In an age when the differences between Democrats and Republicans are marked by deliberately divisive rhetoric, it’s fascinating to recognize that there was a time, among national political candidates, when bland was beautiful, when the whole point of campaigning was to bank on personal appeal. It often worked: an acquaintance of my mother was a big supporter of Vice-Presidential candidate Dan Quayle because she found him “cute.” Good looks and personal magnetism are still, of course, highly useful in politics. But what’s striking about The Candidate is that neither man dares to really express an opinion. After seeing the film, I checked on the actual U.S. Senators who represented California in the 1960s and 1970s, discovering that most of them were an undistinguished lot. Though the serious and hard-working Alan Cranston held one of the California seats from 1969 to 1993, the other passed through the hands of Pierre Salinger (JFK’s former press secretary, who served less than a year), George Murphy (a Hollywood song-and-dance man), John Tunney (a young lawyer with Ivy League cred), and S.I. Hayakawa (a noted linguist and university president who entered the Senate at age 71). Hayakawa, who was embraced by conservatives after he came down hard on student protestors at San Francisco State, is best remembered for dozing off during Senate hearings.

It’s Tunney who comes closest to Redford’s character. The son of champion heavyweight boxer Gene Tunney, he was propelled into politics by name recognition, a Ted Kennedy link (they were law-school roommates), and clean-cut youthful good looks. What did he accomplish? Not much.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers