Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 56

June 12, 2020

Women in the Middle . . . of a Nervous Breakdown

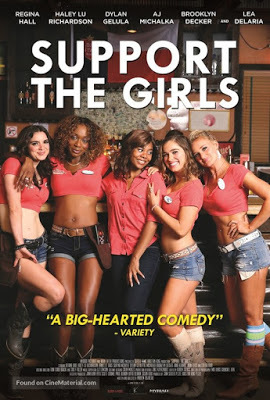

You can’t think of two more dissimilar film projects than the 2018 indie comedy, Support the Girls , and the oblique new thriller, Shirley. They have, though, one thing in common: both feature mid-life women in positions of authority who are striving mightily to cope with the hand they were dealt.

Support the Girls is a big-hearted (and big-busted) romp set in a down-home sports bar that features nubile young waitresses in short shorts and skimpy pink T-shirts. (Think a localized version of Hooters.) The clientele is mostly blue-collar: they’re loud and raucous, but generally harmless, and everyone is constantly being reminded that this is a family place. Riding herd over the goings-on is general manager and mother hen Lisa (the highly appealing Regina Hall), who in the course of one highly-charged day faces every imaginable problem, from a cable-TV malfunction to a would-be burglar in the air duct to a ditsy employee who’s just violated company rules by getting a huge tattoo of basketball star Steph Curry on her midriff.

Though Lisa is quick to listen to everyone else’s problems, she’s got plenty of troubles of her own, including a depressed spouse who’s on the brink of moving out. She tries to organize an off-the-books carwash to assist a battered young woman who’s a member of her crew, but the good deed blows up in her face. And her redneck boss can be crude and downright nasty. It doesn’t help that she’s African-American. So she feels rankled by such absurd policies as the rule that allows only one waitress of color on any shift. By the time she’s been fired (yet again) by her capricious superior, there seems nothing for it but to interview for a job with an upstart rival hot spot named Man Cave. What keeps her going, though, is the camaraderie she feels with the “girls” who have been under her wing.

Sbirley couldn’t be more different in its tone and its atmosphere. It’s basically a four-hander, set in the leafy college town of Bennington, Vermont circa 1950. Two couples living in the same large, rambling house form an unlikely quartet. Rose and Fred are newlyweds. She is newly pregnant; he has been hired by Bennington College as a young prof and assistant to a faculty superstar, the critic Stanley Edgar Hyman (played with panache and conviction by Michael Stuhlbarg). Stanley’s deeply neurotic wife and verbal sparring partner is Shirley Jackson, already the author of an unforgettably eerie story, “The Lottery.” She’s on the brink of writing her second novel and moving toward such major gothic fiction as The Haunting of Hill House and We Have Always Lived in the Castle. Shirley is played by the hugely versatile Elisabeth Moss, lightyears away from her naive but determined Peggy Olson in Mad Men. Though the philandering Stanley has his pick of the campus coeds, the center of the ménage is Shirley, with her barbed witticisms, unexpected kindnesses, and tendency to dominate any gathering she’s in. There’s something of a Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf quality at work, with the older couple manipulating the younger one for their own emotional satisfaction. But Shirley is also—first and foremost—a writer, and her fascination with Rose takes on a life of its own as she weaves it into her current manuscript.

The real Jackson/Hyman marriage, as chronicled in Ruth Franklin’s prize-winning biography, contained four children who are definitely not in evidence here. But the perverse aspects of the actual marital relationship are used by the filmmakers to shed a dark light on this fascinating film.

Michael Stuhlbarg and Elisabeth Moss (she looks remarkably like the real Shirley Jackson)

Michael Stuhlbarg and Elisabeth Moss (she looks remarkably like the real Shirley Jackson)

Published on June 12, 2020 10:39

June 9, 2020

Who Was That Masked Woman?

When I was a student living in Japan, I couldn’t help finding strange the willingness of my Tokyo contemporaries to slap on a surgical mask whenever they felt a sniffle. No, I personally didn’t want to walk around looking like Dr. Kildare. But now, thanks to the onset of COVID-19, mask-wearing in public has become a social necessity. It is also, at one and the same time, a protective measure, a form of political commentary, and (weirdly enough) a fashion statement.

All of which has made me look back on the history of movies to explore the many ways that masks have figured into our favorite films. First, I guess, came the westerns. We all tend to anticipate that a man wearing a bandana tied around his nose and mouth is up to no good: if his face is half-concealed by a piece of fabric, he’s probably planning to rob the stagecoach or commit some other dastardly crime. On the other hand, he might be the Lone Ranger, a long-popular Old West fighter for truth, justice, and the American Way. (For whatever reason, the Ranger concealed only the area surrounding his eyes with his domino mask, so he wouldn’t have had much protection from germs in a pandemic.)

Masks have also been favored to shield the faces of more modern cinematic bad guys, like cat burglars and thieves of all sorts. Sometimes their masks are simple and sometimes elaborate, like the whole-head rubber Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter masks worn by bank-robbing surfers in Point Break (2015). The frothy Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) contains a comic scene (see below) in which Holly Golightly (Audrey Hepburn) and her beau (George Peppard), out on a lark, contemplate shoplifting in a five and dime store. They scurry out the door wearing cheap plastic cat and dog masks they haven’t bought.

Masks can be romantic, allowing for secret meeting and mingling: see all those masked balls in films like Romeo and Juliet. They can hide tragic secrets, concealing horrifying blemishes in various versions of The Phantom of the Opera as well as The Elephant Man. A mask and hood can conceal identity as well as striking terror into bystanders if a great many masked and hooded men gather together for a common purpose. This, of course, is the logic behind the garb of the Ku Klux Klan, who are painted as heroes in Birth of a Nation and as something far, far worse in a number of other films. (The fact that their regalia is so all-concealing is used to comic effect in the Coen brothers’ 2000 hit, O Brother, Where Are Thou?)

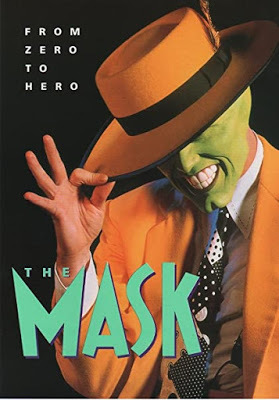

One Hollywood movie titled Mask (1985) does not in fact contain masks at all. It is the poignant semi-biographical story of a young man suffering from a rare disease called craniodiaphyseal dysplasia that distorts his face into a grotesque “mask.” No surprise that this film, directed by Peter Bogdanovich and starring Eric Stoltz, won one of the first Oscars given for achievement in makeup. On the other end of the spectrum, there’s 1994’s The Mask, in which a nebbishy bank clerk played by Jim Carrey comes upon a magical mask that transforms him into a raucous gangster with massive superpowers.

One message of The Mask might be that we can do amazing things when our inner identity is safely concealed. All I want right now is a not-too-ugly, not-too-cumbersome facemask that will protect me (as well as those around me) from passing on a deadly disease. My inner identity will have to wait a while to be able to emerge unscathed. Alas.

Published on June 09, 2020 11:25

June 5, 2020

Senioritis: Is Hollywood Rediscovering Ageing Boomers?

It’s not easy being (ahem!) a person of a certain age. In the COVID-19 era, Seniors are considered particularly vulnerable. We’re constantly warned about interacting with others, and so we’re stuck at home with our TV sets, watching the young and the beautiful cavort and canoodle. And then there are those commercials, reminding us of the failings of our bodies, and recommending denture creams, diabetes cures, and Viagra. (Thank heavens for cable!)

I applaud Erica Manfred, a fellow member of the American Society of Journalists and Authors, who has managed to turn her age into an asset. As a longtime Florida-based freelance journalist, she now specializes in the needs and aspirations of senior citizens. She writes about technology, health, and financial matters from a senior perspective. And she also has her eye on the entertainment world, chronicling how Seniors are portrayed on both the big and the small screens. On a site called Senior Planet she writes approvingly about Game of Thrones, praising the long-running series for making its elder characters—like Diana Rigg’s Olenna Tyrell—some of the saga’s most complex and interesting.

In a 2015 piece on the same site, she compares two dramatic films that showcase ageing rockers looking back on what they gave up to become who they are. In Danny Collins, Al Pacino plays a once-heartthrob who now makes a tidy living playing nostalgia gigs, all the while consumed with self-loathing. Ricki and the Flash, which was Jonathan Demme’s final feature, puts the spotlight on Meryl Streep as an Indianapolis wife and mother who long ago broke with her family to launch a showbiz career. She’s now a music-industry also-ran, working as a checker in an L.A. supermarket while also headlining the house band at a rowdy Tarzana hangout called the Salt Well. But she’s suddenly summoned back home when a crisis befalls her grown daughter (played by Streep’s actual daughter, Mamie Gummer), and the rest of the film deals with her unsteady reconciliation with the family she left behind. As Manfred sagely puts it, “There’s nothing all that new about regret and remorse, but Ricki and the Flash might have put its finger on a predicament that’s fairly unique to aging Boomers; we were the first generation to claim self-fulfillment as our birthright, and many of us chose to put duty and responsibility aside to follow our dreams.” She also notes, “Women, especially, grapple with family versus career, and may have given up one for the other. As Ricki says bitterly at one point, ‘No one blames Mick Jagger for leaving his family to play music.’”

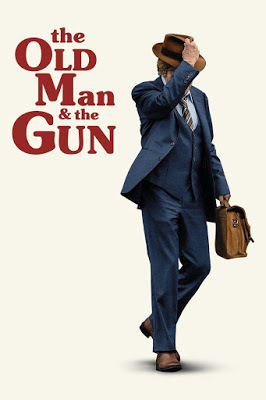

For TheAtlantic.com, Manfred highlights what she sees as “the encouraging greying of Hollywood.” Noting the enormous box office success of The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel and its sequel, she believes that the movie industry has discovered the growing power of older audiences at the box office. The upshot, she feels, is that more and more recent movies make room for characters who challenge our assumptions about ageing. As a result, some of our best actors are given an opportunity to play juicy roles that go far beyond geriatric stereotype: see Robert Redford in The Old Man & the Gun, Jonathan Pryce and Anthony Hopkins in The Two Popes, Liam Neeson as a credible action hero in a whole slew of suspense dramas. Among older actresses are Lily Tomlin toplining Grandma, Sally Field in Hello, My Name is Doris, Blythe Danner in the romantic and poignant I’ll See You in My Dreams. And of course Tomlin and Jane Fonda TV’s Grace and Frankie boldly exploring the late-in-life years.

Published on June 05, 2020 12:22

June 3, 2020

Enter the Dragon: Space Travel American-Style

Frankly, I’m too heartsick right now to focus on what’s surely on the minds of most Americans: the sad, horrible aftermath of racist actions by four cops in Minneapolis. Instead I’ll try to concentrate on the one good thing that happened this past weekend. I mean the successful launch of the Dragon, sending two American astronauts up to the International Space Station. It’s the first time since 2011 that astronauts have been launched from American soil, and the first time in history that a private spacecraft has been used to launch humans into orbit. A triumph all around for SpaceX, whose founder Elon Musk has recently generated far more negative headlines for demanding that, in the wake of the COVID pandemic, his Tesla factory be allowed to violate state safe-at-home orders.

Frankly, I’m too heartsick right now to focus on what’s surely on the minds of most Americans: the sad, horrible aftermath of racist actions by four cops in Minneapolis. Instead I’ll try to concentrate on the one good thing that happened this past weekend. I mean the successful launch of the Dragon, sending two American astronauts up to the International Space Station. It’s the first time since 2011 that astronauts have been launched from American soil, and the first time in history that a private spacecraft has been used to launch humans into orbit. A triumph all around for SpaceX, whose founder Elon Musk has recently generated far more negative headlines for demanding that, in the wake of the COVID pandemic, his Tesla factory be allowed to violate state safe-at-home orders. Hollywood has long had a yen to make cinema in outer space. Fascination with the challenge of filming space travel has led to movies of all sorts, both the goofy (like Dark Star, which began as a student film, jumpstarting the career of John Carpenter) and the high-minded. When Ron Howard shot Apollo 13 in 1995, NASA so badly wanted an accurate record of the aborted moon mission that it allowed for Zero-G filming on the training jet fondly nicknamed “the vomit comet.” These days CGI allows for a far more elaborate suggestion of weightlessness, as seen in such films as Gravity, Interstellar, and The Martian. But I’m still personally partial to Roger Corman’s depiction of space travel on the cheap, going all the way back to 1958’s War of the Satellite. This quickie Corman response to the launch of Sputnik is hilarious if seen in the company of knowledgeable aerospace engineers. And it’s pretty funny no matter your level of outer-space expertise.

Somewhat in the Corman spirit of fast and cheap filmmaking using whatever resources are available is a very short film that fairly proclaims itself “the first sci-fi movie filmed in space.” This 2008 space oddity (see below) is grandiosely titled Apogee of Fear! Its credited cast consists of six astronauts—both American and Russian—aboard a Soyuz TMA 13 in near earth orbit in 2008. (Somehow, despite the three Russian names in the credits, only one apparently shows up on camera.) There’s something of a plot, though not much. Suffice it to say that the story involves dropping oxygen levels, weightless space-juggling, the search for aliens, and a cameo appearance by the director’s mother. Highlights include some gorgeous out-the-window space photos, a score that would give John Williams pause, and some jokey credits meant to amuse space nerds. We’re warned at the start that “some material may be too advanced for developing worlds,” and that the film “contains Krell Physics, Black Obelisks, and Klaatu Barada Nikto.” .(Yes, see 1951’s The Day the Earth Stood Still.) All hail second-generation astronaut Richard Garriott who directed, produced, and starred in this oddball spaceball gem.

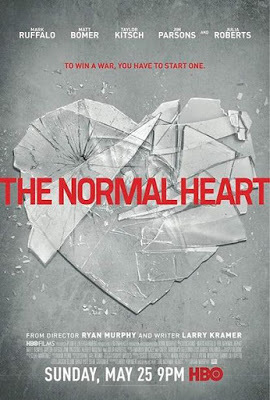

Meanwhile, I would be remiss to ignore the passing of Larry Kramer, writer and activist, who survived 30 years following an AIDS diagnosis. Hollywood remembers Kramer as a talented screenwriter who was Oscar-nominated for adapting D.H. Lawrence’s Women in Love into a 1969 film directed by Ken Russell. And Kramer’s own 1985 stage play, The Normal Heart, which bravely showcased the scourge of AIDS, eventually became a 2014 TV drama. But Kramer was best known as a man who wouldn’t keep quiet about injustices done to the gay community. His outspoken championing of AIDS-related medical issues through such organizations as Act Up is a model for how to use protest in a constructive way.

Published on June 03, 2020 09:33

May 29, 2020

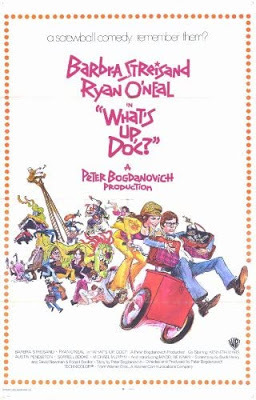

Getting Down with “What’s Up, Doc?”

In the midst of a pandemic, a zany movie comedy sounds like a refreshing change of pace. And they don’t come more zany than What’s Up, Doc? This 1972 screwball comedy helmed by Peter Bogdanovich is clearly meant to evoke such golden-age delights as Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant romping with a pet leopard in Bringing Up Baby. In line with that 1938 classic, What’s Up, Doc? features an outlandishly mismatched couple—he a stuffy academic, she a full-blown kook—who fall for each other in the course of some dizzily nonsensical adventures. In What’s Up, Doc? the leads are played by Ryan O’Neal, coming off of the seriously saccharine Love Story, and Barbra Streisand, already an Oscar winner for Funny Girl.

In the midst of a pandemic, a zany movie comedy sounds like a refreshing change of pace. And they don’t come more zany than What’s Up, Doc? This 1972 screwball comedy helmed by Peter Bogdanovich is clearly meant to evoke such golden-age delights as Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant romping with a pet leopard in Bringing Up Baby. In line with that 1938 classic, What’s Up, Doc? features an outlandishly mismatched couple—he a stuffy academic, she a full-blown kook—who fall for each other in the course of some dizzily nonsensical adventures. In What’s Up, Doc? the leads are played by Ryan O’Neal, coming off of the seriously saccharine Love Story, and Barbra Streisand, already an Oscar winner for Funny Girl. He’s Howard Bannister, a bespectacled midwestern paleontologist who’s come to San Francisco in hopes of a grant to research the musical achievements of cavemen striking igneous rocks. (He’s also under the thumb of a domineering fiancée, played in her feature film debut by the late, great Madeline Kahn.) The interloper who eventually unleashes his wild side is Judy Maxwell, an outrageous young woman who seems to have no other motive than to cause complete and utter chaos in Howard’s life, for his eventual betterment, of course. San Francisco plays itself, complete with cable cars, dizzyingly steep hills down which to careen, and a bay into which all the main characters will inevitably fall.

The script of What’s Up. Doc? has a remarkable pedigree. One of its credited screenwriters is Buck Henry, only a few years removed from his brilliant script for 1967’s The Graduate. Also contributing to What’s Up, Doc? were David Newman and Robert Benton, who’d written Bonnie and Clyde. So three screenwriting icons from 1967 had a hand in scripting What’s Up, Doc?, which is -- not surprisingly -- crammed full of action and wit.

So why didn’t I enjoy it more? Maybe it was my fragile mood. Still stuck in quarantine, I’m not easily amused. And though the actors played their parts with conviction, I didn’t like them enough to root for their eventual success. One particularly sour note for me was Madeline Kahn’s portrayal of the shrewish fiancée, Eunice. With her heavily lacquered hair (a wig, as we discover) and her braying voice, she is the classic stereotype of the marital shrew, from whom the red-blooded American boy-man needs to be liberated. But in watching the film, I couldn’t entirely forget how its maker, Peter Bogdanovich, had dumped his wife and longtime artistic partner, Polly Platt, for Cybill Shepherd while making his previous film, The Last Picture Show.

Bogdanovich, barely 30, was – on the heels of The Last Picture Show – the hottest thing in Hollywood. It was the era of the youthful auteur, the Boy Wonder so hip that anything he touched turned to showbiz gold. That description fit Bogdanovich (a Roger Corman alumnus who’d directed his first feature in 1968) like a glove. Not only did he aspire to write, produce, and direct—he also found a way to be a featured performer, as he was in his big Corman break-out film, Target, where he shared scenes with Boris Karloff. To put it bluntly, the guy had (and still has) chutzpah.

This is certainly revealed in the film’s trailer, in which Bogdanovich, and not his stars, is the central focus. Sure, it’s intended to be spoofy, mocking the “voice of God” narration that insists the young director is “using the camera as Heifetz uses a Stradivarius.” But Bogdanovich’s cleverness is the whole point of this over-the-top exercise. For me, anyway, enough is enough.

Published on May 29, 2020 10:05

May 26, 2020

Shedding a Tear for Those Who made Us Laugh

Alas, no Fred Willard on this poster

Alas, no Fred Willard on this posterYesterday was Memorial Day, a traditional time for Americans to remember those who lost their lives on the field of battle for the sake of our democracy. Sometimes I observe the day with posts about films like Glory, Dunkirk, and Apocalypse Now, movies that celebrate great hard-fought victories or explore those conflicts in which American lives were sacrificed in vain. This year, given the challenges we’re all facing, I’m going another route. One day after Memorial Day, I’m paying tribute to men and women who are no longer around to amuse us, to lift our spirits in dark times. Yes, I mean entertainers.

Some will associate Jerry Stiller with Seinfeld, or The King of Queens. And of course it’s well known he was Ben’s dad. But oldster that I am, I associate him with his wife and comedy partner Anne Meara, and their very funny radio spots plugging Blue Nun wine. The wine itself was mediocre, but the popular ads—in which he offers her “a little Blue Nun,” and she assumes he means a Catholic sister (see below for an audio clip), helped the distributors sell more than a million cases.

We’re also saying farewell to Fred Willard, the lovable master of mediocrity. (The New York Times described his specialty as playing men “gloriously out of their depth.”) He earned four Emmy nominations on behalf of his roles on Modern Family and Everybody Loves Raymond. But he’d spent 30 years in the entertainment industry before he leaped into the public consciousness through Christopher Guest’s semi-improvised comedies, including Waiting for Guffman and A Mighty Wind. Everyone’s favorite Fred Willard portrayal is doubtless that of the clueless TV commentator in Guest’s 2000 hit, Best in Show. Offering color commentary at a prestigious (read: snooty) dog competition, Willard cheerfully reminded viewers that in some nations dogs get eaten.

And then we lost a blast from the distant past. When I was little, Leave it to Beaver was essential TV viewing. It was the usual family sitcom. Among the younger generation living in the Cleaver household, there was little Theodore (nicknamed The Beaver), and his teenaged brother Wally. And, of course, there was Wally’s smarmy pal, Eddie Haskell, he who was always kissing up to the adults, while also secretly plotting mischief. Eddie was played by Ken Osmond, who died this past week at age 76. Once Beaver went off the air, Ormond found himself typecast, and he eventually quit show biz. Unlikely as it seems, he ended up as an LAPD motorcycle cop. No, not – despite rumors to the contrary – a porn star.

I also salute two actors not specifically known for comedy. Shirley Knight is most associated with stage work, but accrued two Oscar nominations while still in her twenties for roles in screen adaptations of challenging works by Tennessee Williams and William Inge. I’ll never forget her in Dutchman (1966), a terrifying indie based on a rawly racial play by Amiri Baraka (aka LeRoi Jones) A sexy white woman meets a buttoned-down black man (Al Freeman Jr.) on a steamy subway train: fireworks ensue.

On the international front, we’ve also lost the great Indian actor, Irrfan Khan, dead at 53. Most of Khan’s hundreds of credits are in Indian films, but he also appeared in such American movies as Life of Pi, Jurassic World, and—poignantly—opposite Kelly Macdonald in 2018’s Puzzle. But I’ll always love the dignity he brought to The Lunchbox, the tender Mumbai-set story of an unhappy wife whose lovingly packed lunch gets delivered to a lonely widower .instead of to her ungrateful husband.

Hail and farewell.

Published on May 26, 2020 11:12

May 22, 2020

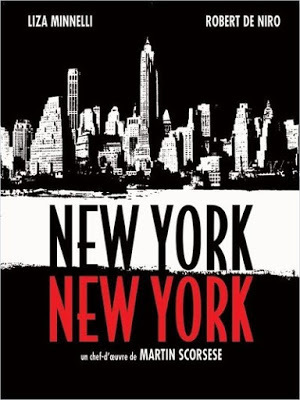

YouTubing Our Way Through a Pandemic: Spike Lee Pays Tribute to New York, New York

In these difficult days (boy, how I’ve come to loathe the word “unprecedented”), we’re all looking to be entertained as we hunch in front of our computers or curl up with Zoom on the living room couch. Since we cinema buffs can’t go to the movies, movies are coming to us. And if we miss live theatre, enterprising stage performers are finding ways to do what they do best and then transmitting it over the airwaves. It’s not enough, of course, but for now it will have to do.

A friend alerted me that one of her favorite New York stage companies, the Irish Repertory Theatre, was sharing with its patrons a special Zoom production of Molly Sweeney, a 1994 play by Irish playwright Brian Friel. This production, by an award-winning dramatist who’s been called the Irish Chekhov, is a far cry from the bits of song and storytelling that have been passing as theatre on my iPad of late. It’s a full two-act play, but one superbly suited to the odd-ball medium we’re all using in the era of COVID-19, because it’s entirely made up of monologues. There are a total of three characters: Molly, her husband, and the doctor who restores her sight after forty-some years of blindness. They trade off narrating her story, one that starts with joy and ends in great sadness. Because in many ways this is a play about isolation, the fact that the three characters are filmed in separate venues makes all the dramatic sense in the world. Bravo to a company dedicated to preserving and presenting the work of Ireland’s many dramatic masters.

That production of Molly Sweeney, which starred Geraldine Hughes and two talented actors, was performed on a limited schedule for a limited audience. But on YouTube, anything goes, including Broadway performers (and Broadway wannabes) performing—from their separate spaces—selections from famous musical numbers, like the opening scene from A Chorus Line. Sometimes they aspire to be timely, like this hilarious Covid-inspired version of “The Cell Block Tango” (renamed the Zoom Block Tango) from Chicago.

In a more serious vein, the ever inventive Spike Lee—filmmaker extraordinaire—has compiled a breathtaking three-minute inematic paean to his home town. To the upbeat strains of Frank Sinatra singing “New York New York,” he gives us a tour of all the boroughs, emphasizing the charm of their landmarks (skyscrapers, brownstones, bridges, Broadway) along with the fragile beauty of springtime blossoms. It’s only gradually that we glean the fact that the streets of Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens are nearly bare, rather than teaming with life. Yes, Lee shows us that the city that doesn’t sleep has become something of a ghost town. The usual New York traffic jams are no more. Taxis have been replaced by ambulances speeding toward hospitals, where heroes in masks and gloves whisk desperate bodies into intensive care. Central Park is crammed full of medical tents for COVID sufferers, and a hospital ship is moored just offshore. It’s a poignant view of a town that has starred in hundreds (maybe thousands) of films as a place of optimism, romance, and upward mobility.(See, for instance, Woody Allen’s Manhattan.) But through it all Sinatra’s voice resonates with its signature insouciance. You can take it as irony. But the Sinatra tune also seems to suggest that New York will once again rise from the ashes. And if we can survive the pandemic there, we’ll make it anywhere.

I love the fact that Lee wears his heart on his sleeve, and that he shares his love for New York City with us all

With thanks to Beth Phillips, Hilary Bienstock Grayver, and Susan Henry for sharing too.

Published on May 22, 2020 13:13

May 19, 2020

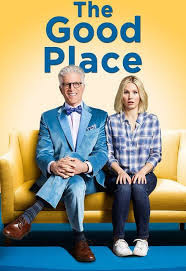

Forking Around With Ethics in “The Good Place”

I feel like a philosophy major on a serious bender, thanks to the hours I’ve spent watching The Good Place.

In normal times, I rarely watch television. Movies are my beat, and it wouldn’t occur to me to binge-watch a TV series. Hell, I wasn’t even quite sure how to turn on Netflix. All that ended in mid-March when I found myself a prisoner in my own home, thanks to COVID-19. I’ve since watched all of The Crown and am finally catching up on Mad Men. Not to mention The Great British Baking Show, which fueled my enthusiasm for baked goods (yum!) but also reminded me of all the culinary skills I’m lacking.

Now, though, I’m hooked on a series that’s about as far-fetched as it can get. While mortality is in the air both in real life and on television, this is a show that skips death and goes straight to the afterlife. The Good Place follows Eleanor Shellstrop, a rough-around-the-edges young woman from Phoenix who likes to party hard and satisfy her own personal needs at the expense of others. As played by Kristen Bell, the post-mortality Eleanor is brash, foul-mouthed (to the extent that the rules allow her to swear), and undaunted by any obstacle in her path. A cuddly heroine she is not. The comrades she meets in the afterworld are a motley lot. There’s Chidi Anagonye,, an earnest Senegalese professor of ethics and moral philosophy who gets the unlikely assignment of being Eleanor’s Good Place soul-mate. There’s Tahani Al-Jamil, a remarkably tall, remarkably pretty, incredibly snobbish Brit likes to boast of her history of philanthropy and her web of celebrity connections. And there’s Tahani’s official soul-mate, a young Taiwanese monk who’s taken a vow of silence. But wait—there seems to have been a mistake. He’s actually Jason Mendoza, a part-time DJ and drug dealer (as well as full-time doofus) from Jacksonville, Florida.

Two more essential characters fill out the cast. Presiding over this neighborhood of the Good Place, a Disneyland-ish space full of fountains, frozen yogurt stands, and a giraffe or two, is Michael, its architect, and a being whose outrageous secrets are gradually revealed as the series moves forward. He’s played by Ted Danson, an actor adept at showcasing a wide range of outlandish emotions. (No question that in real life Danson has a wicked sense of humor. Long ago, when dating Whoopi Goldberg, he showed up at a Friars Club roast in her honor wearing blackface and proceeded to eat a watermelon.)

And of course there’s Janet, who’s not easily described. She looks like your basic cute flight attendant type, but she has all the knowledge of the universe at her fingertips. Which doesn’t stop her from the occasional emotional trauma as she runs through a series of highly inappropriate boyfriends. .

All this may sound goofy indeed, but underlying it all are serious questions about ethics, with nods to philosophers like Aristotle, Descartes, and Kierkegaard. Under Chidi’s tutelage, Eleanor truly weighs questions of good and evil, evolving from a selfish brat into a far more empathetic woman. And – though she’s not immune to backsliding – her new outlook helps her weather the challenges that Michael and others set before her.

One thing that’s particularly refreshing: although Eleanor and her afterlife peers demonstrate at times all manner of bad behavior, no one on the series is ever cruel on the basis of religion, race, or political leaning. This is the most diverse cast I’ve ever seen on television. Some of them believe in eternal torture, but racist they are not.

Published on May 19, 2020 11:03

May 15, 2020

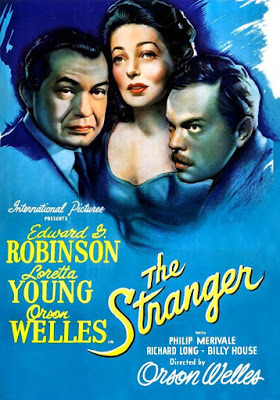

Time Bound: Orson Welles’ The Stranger

The Stranger is the title of more than 20 motion pictures from around the globe, some of them dating back to the silent era. While sheltering at home in the wake of COVID-19, I happened on one of them, the 1946 feature that was Orson Welles’ third film. Ironically enough, The Stranger was far more successful at the box office than Wellesian masterpieces like Citizen Kane. True, it had a somewhat flawed production history—Welles himself felt that script changes mandated by producer Sam Spiegel undermined the gravity of the project—but the film’s air of creeping menace seems right at home today. What’s different now is that the danger we feel is invisible, an eerie manifestation of the dark side of the natural world. In The Stranger, danger has all too human a face.

The setting of The Stranger, immediately following World War II, is key here. The action takes place in an idyllic American town where no trace of the ravages of war can be discerned. The only aspect of town life that seems to be amiss is that its venerable church clock, a relic (complete with revolving figures) that was long ago imported from Europe, no longer works. But a professor at the distinguished local prep school, a great lover of old clocks, has been hard at work to bring it back to life.

What nobody knows is that the good professor, known locally as Professor Charles Rankin, is in fact Franz Kindler, a dedicated Nazi who had recently presided over a death camp. Though he fits in nicely in this small American town, to the extent that he’s marrying the daughter of a Supreme Court Justice, he will stop at nothing (including murder) to keep his former identity a secret. Director Welles plays Rankin with his usual bravado: he’s the kind of man you love to hate. Also toplined in the cast are Loretta Young and Edward G. Robinson. She, as Rankin’s new wife, is a pretty but vacuous presence, one who rather surprisingly accepts her husband’s excuses and keeps his secrets—until, at last, she doesn’t. Robinson, plays the role of a newcomer to town, a war crimes investigator following a trail that leads to Rankin. It’s surprising to learn that Welles himself wanted this role to be played by Mercury Theatre regular Agnes Moorehead, feeling she’d be a more unlikely and thus more interesting sleuth on Rankin’s trail. But of course the acerbic Robinson is always fun to watch.

Welles decked out The Stranger with the trappings of film noir. He also lavished on this production the kind of bravura camera work and editing that make Citizen Kane so spectacular. Perhaps it’s fair to say that he goes a bit overboard here, with all manner of mirror shots, Dutch angles, and moments of deep focus. Especially during the climax that (of course) takes place in and around that clock tower, he pulls out all the stops. (The tower itself makes the one used by Hitchcock in Vertigo seem a wee bit bland by comparison.) Detracting from the overall effect are plot holes through which you could drive a Sherman tank. Or maybe I’m the only one annoyed by how many people can successfully go up and down a sabotaged ladder.

In one respect, realism prevails. The Stranger was the first feature film to incorporate actual Nazi concentration camp footage, which is screened by Robinson’s character to establish Rankin’s culpability. It’s not the most horrific footage that would eventually be revealed to the American public, but it’s good to see truth having its day.

Published on May 15, 2020 10:14

May 12, 2020

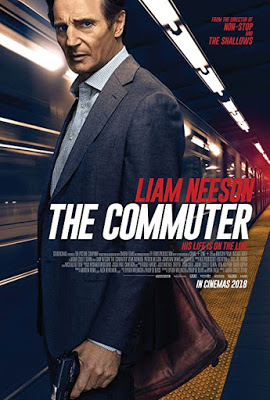

Geriatric Derring-Do: Liam Neeson as “The Commuter”

Old people, we’re told, don’t have much social value. Because the COVID-19 pandemic seems to particularly target elders 65 and older, there are those—impatient to return to post-quarantine life—who feel oldsters should be willing to self-sacrifice so that the economy can resume its normal function. Maybe it makes sense that, as in Midsommar, the elderly should gladly give up their lives for the sake of the social organism. But I’m not convinced senior citizens are so easily expendable. Exhibit A: Liam Neeson.

Neeson was 65 when he made The Commuter in 2018. This was hardly the first action movie in which he revealed a talent for geriatric derring-do. Though his star-making role in Schindler’s List hardly qualified him as an action hero, he has specialized (particularly since Taken in 2008) in playing tough-minded good guys who belie their age by springing into action when the chips are down. On planes, trains, and automobiles, he’s done what a man has to do, saving his family (not to mention humanity in general) by taking down baddies by any means necessary.

A commuter train out of New York City is the basic locale for most of The Commuter. As Neeson’s Michael McCauley heads for home after a particularly bad day at the office, all hell seems to break loose, to the extent that we housebound folk might suddenly feel ourselves lucky to be living in quarantine. On the train with him are an assassin, a corpse, a damsel in distress, some innocent bystanders (or are they?), a satchel full of money, and a mysterious femme fatale (Vera Farmiga) who appears to be behind the whole thing. There’s also the inevitable buddy who turns out to be Not What He Seems. McCauley, though baffled by what’s going on, quickly springs into action, using every ounce of his physical agility and his mental smarts to figure out the right course of action This includes crawling underneath the train carriage at one point and finding a way to de-couple the last car at another. (Props here to the stuntmen: it certainly all looks real, and tremendously scary.)

To be honest, I couldn’t explain the film’s convoluted plot if I tried. But that hardly matters. The sole purpose of a movie like this one is to rev up the viewer’s adrenaline. It’s a classier, more star-driven version of what we aimed for when I was the story editor for Roger Corman at Concorde-New Horizons. making flicks whose sole purpose was to provide excitement. (Corman generally upped the ante by finding a way to sneak in some T&A, but all the blood and gore here is strictly PG-13.).

Though Neeson has had some more complex roles over the years (for instance, he played sex researcher Alfred Kinsey in 2004), there’s evidence his spate of action films has been good to him. As he approaches age 70, he seems to be taking on multiple roles every year. IMDB tells me he currently has three films in post-production, two in pre-production, and one supposedly filming, though of course the current pandemic has had something to say about that. And he’s just signed to play the role of Philip Marlowe in a new take on Raymond Chandler’s classic detective hero.

It bears noticing that our current presidential candidates of both parties are septuagenarians. We can certainly argue about the wisdom of entrusting our ship of state to someone of advanced years. But if a seventy-year-old can be elected President of the United States, there’s no reason we can’t be treated to a septuagenarian who really kicks butt.

Published on May 12, 2020 12:28

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers