Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 60

January 23, 2020

The Four Little Women and How They Grew

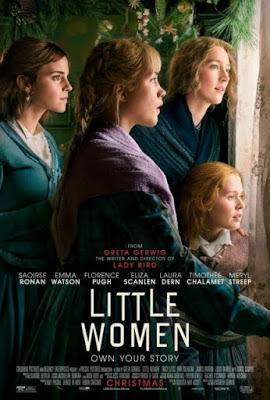

“Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents.” So Little Women begins on the page, and so previous screen versions have always begun: with the four March sisters lamenting the poverty they face while their father is off in the Civil War. One striking feature of Greta Gerwig’s new version is that it dares to break the mold and play with the book’s chronology.

Growing up I was a serious Louisa May Alcott fan. I read most of Alcott’s novels, which fall into the category you could call 19th century YA, and I later persuaded my kids (yes, my son as well as my daughter) to enjoy Little Women, as I had. More recently I’ve read Alcott biographies, and also the fictional March (about the Civil War escapades of Jo’s father), plus Anne Boyd Rioux’s scholarly Meg, Jo,Beth, Amy: The Story of Little Women and Why It Still Matters. So I guess you could call me a true believer. . As such I’ve always been partial to the 1933 George Cukor screen adaptation, at least to Jo as portrayed by Katharine Hepburn. Alcott’s original description of Jo, her own literary alter ego, was that she was “tall, thin, and brown, and reminded one of a colt, for she never seemed to know what to do with her long limbs, which were very much in her way.” No other Jo in my memory comes so close to this physical description as Hepburn, and her striking combination of awkwardness, intelligence, and occasional pig-headedness makes her my nostalgic favorite. The 1949 musical version features, alas, June Allyson warbling about being “the man of the family now that Papa is away from home.” Allyson is just too cute and perky to be my Jo. In this iteration, directed by Mervyn LeRoy, Janet Leigh makes a conventionally pretty Meg, Margaret O’Brien an appropriately fragile Beth, and Elizabeth Taylor an extremely unlikely Amy, overgrown and wearing a distracting blonde wig. (Yikes!)

Hollywood then left the story alone until 1994, when an actual female director, Gillian Armstrong, took it on. Her version, much loved by many women I know, conveys a nice warm sense of family, presided over by a glowing Marmee (the mother character) in the person of Susan Sarandon. I’ve admired the young Claire Danes as Beth and the even younger Kirsten Dunst as a perfect snip of an Amy, though at 12 she could not play Amy’s later scenes and had to be replaced by Samantha Mathis. It all looks gorgeous but I just can’t accept Winona Ryder: too petite and too pretty to ever be awkward, intense Jo.

Greta Gerwig had the bright idea of focusing on Jo’s literary aspirations by starting the film near the story’s end, with Jo living in New York as a fledgling writer. Gerwig’s structure is complex, moving us back and forth in time. Uniquely, she focuses on a Jo who genuinely spurns marriage in favor of a career. How does she handle the fact that Alcott’s Jo does indeed fall in love and get married? There’s a clever twist I don’t think it’s fair to fully disclose; suffice it to say that this is the most “meta” of Little Women adaptations, so that the Jo we meet is in many ways Alcott herself, adapting her family’s story for popular consumption. Other virtues: Laura Dern’s Marmee and Florence Pugh’s Amy are far more complex than usual; Meryl Streep is a hoot as stern Aunt March; and Saoirse Ronan’s uninhibited romping with the boy-next-door, Timothée Chalamet, captures a delightfully warm relationship that she cannot allow to ripen into love.

Published on January 23, 2020 09:10

January 21, 2020

Megxit: Will Harry and Meg Take a Canadian Holiday?

Day after day, the shocking headlines are rolling out of Great Britain, and they don’t have anything to do with Brexit. Harry and Meghan (last names unnecessary) are giving up their status as senior royals! They’re planning to spend a good part of their time overseas (likely in Canada, where Meghan’s grandmother-in-law’s picture is still on the money)! They want to earn their own living (imagine that!) and make their own rules! They no long want to be called by their “royal highness” titles! (I don’t suppose “your royal lowness” is under consideration.)

I’m sure it’s all heartbreaking for Queen Elizabeth and for fans of British traditionalism, of which the U.S. has many. From afar it looks like an easy gig to be a royal: you dress beautifully, visit hospitals, and wave with your fingers stuck together. But from my brief experience at being a semi-celebrity—when I was one of 56 U.S. pavilion guides at the 1970 World’s Fair in Osaka, Japan—I know that it can prove exhausting to be constantly the center of attention. Good behavior at all times is hardly natural or easy. And Meghan’s outsider status has certainly left her wide open to a press that is always on the lookout for snarky scoops.

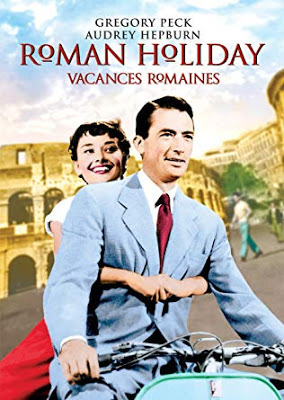

In any case, the situation naturally set me to thinking about movies in which young royals chafe under the pressures they face. Little girls may still want to grow up to be princesses. (Even, I’m told, William and Kate’s daughter Charlotte has this fantasy, notwithstanding the fact that she is a princess for real.) The movies, especially Disney fare like Frozen and the Princess Diariesfranchise, certainly encourage royalty-envy. But the whole situation of a princess struggling to accept the demands of her royal status takes me back a long way to 1953, and Audrey Hepburn’s first major film, the delightful Roman Holiday.

The story of Roman Holiday, which was filmed on location in the Eternal City, is simplicity itself. The young Princess Anne, representing some unnamed European country, is on a state visit to Rome. She’s beautiful and poised . . . and unspeakably bored by all the pomp and circumstance surrounding her visit. That’s why she sneaks out of her royal quarters . . . and finds herself in the company of an ambitious reporter, Gregory Peck, who at first sees in her the potential for a terrific journalistic coup. Soon, of course, he’s charmed by her innocent delight in common pleasures, like eating an ice cream cone in public and zooming through the twisty streets of Rome on a Vespa motorbike. It’s not long before she’s having her long royal locks shorn into a modern style and gotten herself involved in a good old-fashioned fracas that prompts the arrival of the carabinieri. And, of course, she’s come very close to falling in love. The end of the film (as I’m sure everyone has anticipated) is a return to the basic status quo: Anne is back doing her royal duty, and Peck’s character is again no more than a member of the press corps. But while life as a commoner has subtly changed her, her vibrant enthusiasm has softened Peck’s cynical approach to life. It’s a quietly happy ending, particularly for Hepburn, who went home with a Best Actress Oscar.

This movie also won Oscars for Edith Head’s costumes and for its witty screenplay. The latter statuette was presented to Ian McLellan Hunter, who was in fact fronting for the blacklisted Dalton Trumbo. It took forty years for the late Trumbo to be acknowledged as the film’s true author.

Published on January 21, 2020 13:56

January 17, 2020

“Pain and Glory”: Not Lost in Translation

A movie about a successful film director coming to terms with his own past? Sounds suspiciously like Fellini’s 8 ½. But Pedro Almadóvar could never be confused with the Italian master. First of all, Fellini’s alter ego (played by Marcello Mastroianni) is bedeviled by the various women in his life: his ex-wife, his mistress, the idealized woman of his dreams. (The latter is represented on-screen by the luscious Claudia Cardinale.) Almadóvar’s central character, as played in a strikingly complex performance by Antonio Banderas, is more romantically focused on men. But the essential figure in his life is female: his strong, fierce, intelligent mother, who once made sure—despite the challenges of poverty—that her young son got the education he deserved. (In flashback scenes, she’s represented on-screen by another Almadóvar regular, the luminous Penélope Cruz.)

Then there’s the fact that 8 ½.like many of Fellini’s masterworks, is filmed in austere black & white. Almadóvar, more than any other director I can think of, is in love with color: his characters wear electric orange, brilliant red, poison green, as well as bold eye-catching prints, and they live against dazzling backdrops made up of impossible color combinations. I’m told that the home occupied in the film by Banderas’s newly-affluent character, Salvador, is in fact Almadóvar’s own, which clues us in to the fact that they share similar tastes, if not identical life stories.

When first seen, Salvador is literally under water, symbolically drowning from a combination of physical pain, guilt, and lack of artistic inspiration. Invited by a prestigious cinematheque to star in a Q&A celebrating his 30-year-old film, Sabor, he does everything he can to sabotage the evening. Obsessed, because of past memories, with the ravages of addiction, he comes very close to going off the deep end. This is the point in the film where viewers like me start to become deeply uncomfortable: where exactly is this heading?

But an Almadóvar film delights in the unexpected. It occurs to me that this is one way that Pain and Glory echoes, but in reverse, another of the year’s great foreign-language features, the South Korean Parasite. That film won my heart partly for the way it shifted gears from comedy into something far different. In a sense—though I don’t want to oversimplify—Pain and Glory works in the reverse order, immersing the leading character in what seems to be hopeless psychic pain, but then, through some off-the-wall but deeply moving coincidences, pulling him out of it. It’s a victory we savor, leading to a gloriously meta closing scene. (No, it’s not the director and all the people in his life joining hands and dancing in a ring to a Nino Rota score.)

Like Parasite, Pain and Glory (aka Dolor y Gloria) is an Oscar nominee for Best International Feature Film, a renamed category that used to be Best Foreign Language Film. And like Parasite it too is the recipient of major awards, both for Almadóvar and for Banderas’s essential work. Though it’s rare for a foreign-language performance to win an Oscar, Banderas (a much admired actor in both Spanish and English) could conceivably go home with a statuette. Probably not, alas: there’s a Joker in that deck.. But the strength of both Parasite and Pain and Glory should remind us moviegoers not to feel limited to films made in our own language. One small theatre chain in L.A. proudly uses as its slogan “Not afraid of subtitles.” If we insist on seeing only movies made in English, we’re missing out on a whole wide world of great cinema.

Here’s a letter in which Almadóvar himself writes about the autobiographical aspects of this film

Published on January 17, 2020 09:58

January 14, 2020

1917: Mettle, Medals, and Awards

War, as we know, is hell. Still, a war movie is a helluva good way to get awards attention. A war film, by its very nature, deals with a serious subject on a huge canvas. It encourages technical virtuosity along with action, suspense, and an epic sweep. And it’s an overwhelmingly male genre, as compared to, say, Little Women. It may certainly not be coincidence that Kathryn Bigelow, the one female director ever honored by the Academy with an Oscar (for 2008’s The Hurt Locker) was recognized for an Iraq-era war film featuring a virtually all-male cast.

Some war films are rollicking (The Dirty Dozen), some are existentially grim (Platoon and The Deer Hunter), and some are jingoistic, designed to arouse our patriotic enthusiasm (John Wayne’s The Green Beret, but also Dunkirk, which reminds us of the savvy heroics of World War II). Some of the very strongest, like Paths of Glory and All Quiet on the Western Front, use the battlefields of World War I to show us that war should never be glorified, that it brings out not the best but the worst in men.

I’m not what you’d call a fan of the war film genre, but I have to admit that Sam Mendes’1917 blew me away. This film is technically bravura in its use of the camera to involve us in the action: famously, cinematographer Roger Deakins and crew give the illusion of a single take that closely follows two British doughboys through the French countryside on their way to deliver a message on which lives depend. These young leading men are heroic, but not in the way of Gary Cooper’s Sergeant York, who is ace rifleman as well as a saintly savior of his fellow GI’s. Instead Lance Corporals Blake and Schofield are skillfully depicted as average chaps who must rise to the challenge of what is required to them, despite the long odds that they’ll succeed.

It’s a pleasure, of sorts, not to be bogged down in a convoluted plot, involving tricky deviations from the ongoing story. Instead 1917 is a single slog across a no man’s land riddled with pitfalls and pockmarked with corpses of animals and human beings. Which is not to say the film lacks excitement. There are dangers at every turn, and their outcome can not always be predicted. The one-take illusion keeps us breathtakingly close to what’s going on: I have never felt so clearly that I knew what trench warfare was about. But for all the movie’s basic allegiance to reality, it makes room for a surrealistic note. Late in the film, as bodies and minds become battered, there’s an eerie night sequence in the ruins of a devastated town, followed by an ominous incorporating of the plaintive old folk ballad “Poor Wayfaring Stranger.” (This is a purely American song in its origins, so its appearance among a troop of British soldiers seems unlikely—but it beautifully fits the mood Mendes has set.)

Does 1917 have what it takes to nab the Oscar for best picture? Its surprise win at the Golden Globes sent shock waves through the industry, but upon reflection I think this may be the film to beat. I’m no fan of Scorsese’s The Irishman; the powerful but intimate Marriage Story seems to be fading from consideration; and Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood is perhaps too whimsical a treatment of a real-life tragedy to take the top prize. And 1917 has the key virtue of being made by an actual movie studio, not a streaming service. Enough said.

This post was written before the nominations were announced. I haven’t seen Joker, but I suspect it would not make me change my mind.

Published on January 14, 2020 15:09

January 10, 2020

And Here’s to You, Buck Henry: Weird and Funny—with a Stroke

Buck as a hotel desk clerk in "The Graduate"

Buck as a hotel desk clerk in "The Graduate" “Ben and Elaine are married still. . . . . Mrs. Robinson, her aging mother, lives with them. She’s had a stroke. And they’ve got a daughter in college—Julia Roberts, maybe. It’ll be dark and weird and funny—with a stroke.” This pitch for a sequel to The Graduate was the invention of the film’s screenwriter, Buck Henry. He had been invited to the set of Robert Altman’s 1992 Hollywood satire, The Player, which focuses on the increasingly fraught life of a studio development exec, played by Tim Robbins. Altman had told him to be creative. So as part of a bravura opening sequence, Henry pitched to Robbins’ character his idea for The Graduate, Part II, a follow-up to the hit 1967 comedy he’d written (and appeared in) back in 1967.His trademark deadpan delivery made the moment a delicious lampoon of Hollywood’s eternal search for the next big idea, even one that envisions the glamorous Mrs. Robinson as a stroke victim.

How sadly ironic that circa 2016, when I tried to contact Buck Henry for my Seduced by Mrs. Robinson: How The Graduate Became the Touchstone of a Generation, I learned he was too ill to connect with me. The reason: he’d been severely weakened by a stroke. From what I was told, it was no laughing matter. This man of great verbal inventiveness, a two-time Oscar nominee and frequent guest-host on Saturday Night Live, was not up to being interviewed for a book on one of his most memorable film creations.

Happily for me, I got to meet Buck Henry, though it was six months after my book’s 2017 publication. Larry Mantle, the popular host of KPCC-FM’s AirTalk, had launched a film series highlighting movies set in Southern California. The series kicked off at a vintage DTLA movie palace with a screening of Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown. I’d like to think it was an on-air interview I did with Larry on KPCC that inspired him to choose The Graduate as his series follow-up. I was invited to be part of the post-screening panel, which also featured the film’s producer, Lawrence Turman, and film critic Peter Rainer. To my delight, Buck too agreed to appear. No question that the stroke had taken a toll: he showed up in a wheelchair, fussed over by attendants, and the seating was arranged on-stage so that he could favor the side of his body that still pretty much worked.

I was so awed and thrilled to meet Buck backstage that I didn’t get to ask many questions. He did affirm, though, that his birth name was Henry Zuckerman. “Buck,” he explained, was his birth nickname, borrowed from his grandfather. And he made clear that, despite the gag sequence in The Player, he had never actually considered doing a follow-up to the story of Benjamin Braddock and Elaine Robinson. Like Larry Turman, he could not account for why there had been a stag event on the Graduate set that featured topless young ladies cozying up to the male cast and crew members. (I had brought along copies of archival photos proving this happened, but both Buck and Larry swore they didn’t remember a thing about this obviously lively event.)

One question I didn’t have the heart to ask Buck: why he held in his lap a whimsical teddy bear, upon which his withered arm rested. Stuffed animals and Buck Henry did not seem to go together. Still, when he took the stage, I was glad to see his wit was in no way impaired.

Rest in peace, Buck – you’ve earned it!

Here’s a link to the broadcast that was aired after our live event, along with a picture of Buck in his wheelchair.

And here's that scene from The Player.

Published on January 10, 2020 09:54

January 7, 2020

A Film for Those Who Like Their Gems Unpolished

Frankly, I can’t pretend I enjoyed watching Uncut Gems. And anyone who hates the unrelenting pace of today’s New York City should definitely stay away. This film is so loud, so hyperactive, and so profane that it leaves you with barely a moment to catch your breath. Yes, it feels real, but this isn’t a reality I’d personally enjoy spending time in.

That being said, I have to confess I admire what the Safdie brothers have accomplished. Before Uncut Gems, I had never seen anything by Josh and Benny Safdie, the young (ages 35 and 33) indie filmmakers who grew up in the Big Apple and have incorporated its frenetic rhythms into their movies. Their exuberant fascination with the seamy side of New York life is much like that of the early Martin Scorsese, which makes it not at all surprising that Scorsese himself is an executive producer of this film. Vivid characters, rat-a-tat dialogue, spot-on casting, Darius Khondji’s sometimes dazzling cinematography: all these contribute to a view of Manhattan’s Diamond District that is too specific to be disbelieved. Most essential, of course, is the central performance of Adam Sandler, who has earned legitimate kudos for going far beyond the goofy comic roles of his earlier films.

Sandler plays Howard Ratner, a small-time Diamond District jeweler with a big-time gambling problem. His attempt to sell basketball star Kevin Garnett (nicely playing a more naïve version of himself) on a particularly fabulous South African black opal coincides with his desperate need to pay off a massive gambling debt or risk facing the wrath of some particularly twitchy loan sharks. But then there’s also the wrath of his wife, ferociously played by Idina Menzel. She may or may not know about his girlfriend in the city, but she certainly recognizes that he’s been neglecting his three kids for the sake of his personal obsessions.

Obsession is definitely something this film is about. Howard wants to be a good guy—really, he does—but his fascination with the thrill of a big financial score leaves him too hopped up to settle for quiet domesticity in the suburbs. The intensity of his behavior is dialed to eleven. A motormouth at the best of times, he jokes, he flirts, he rants, he cajoles, he connives, he ingratiates himself with those in power and tries to channel what clout he has left against those lower in the pecking order. But he proves not the only obsessive in Unxcut Gems. Kevin Garnett, who in the timeframe of the movie was a Boston Celtic forward involved in a crucial playoff series with the New York Knicks, is obsessed with anything that will bring him luck on the basketball court. The thugs pursuing Howard are not going to be stopped, no matter what. And the pretty young employee who doubles as his girlfriend (newcomer Julia Fox) is loyal to a fault. At first I wondered why in the world she’d cling to a not-so-attractive middle-aged guy with powerful enemies: surely she could do better. I suspect the answer is that she too is obsessed, and obsessions can make little sense at the best of times.

Another theme that sheds light on this film is the randomness of the universe. No one—not Howard, not Kevin, not the loan sharks—can absolutely guarantee what is to come. Throughout scenes depicting basketball games, casino betting, gem auctions, and business shenanigans, we have an uneasy feeling that something unexpected is about to happen. And, sure enough, it does. As the Safdies know full well, that’s the way of the world.

Published on January 07, 2020 12:21

January 3, 2020

The Director Was a Woman

The theory is that Little Women has been largely snubbed by the Golden Globe and SAG folks because few of the men who run those organizations want to see a movie that’s all about GIRLS. The members of the Hollywood Foreign Press, a small and exclusive group, didn’t include a single woman among their Golden Globe nominees for best director and best screenplay. This despite the contributions of, among others, Greta Gerwig (Little Women), Marielle Heller (A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood), Kasi Lemmons (Harriet), and Lulu Wang (The Farewell).

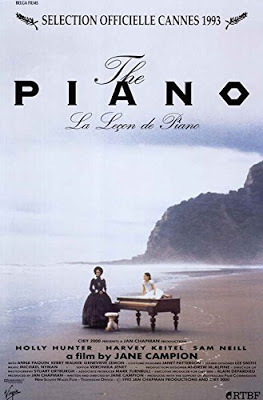

Meanwhile, BBC Culture has just presented the results of its latest polling. After surveying 368 experts from 84 countries, they’ve compiled a list of the 100 greatest films directed by women. Why choose this topic? It came out of the BBC’s realization that after several years of polling on various film-related subjects (greatest foreign-language films, greatest film comedies, greatest American films, and so on), they rarely found women’s achievements represented. I’m sure there are PhD dissertations being written at this very moment as to why it’s so rare for women to helm movies. But it’s fascinating to look back and see the names of women who did something wonderful. Too bad so many of them were working in foreign language cinema. French-speaking women, in particular, seem to prevail. On the list we find six films by the late, beloved Agnès Varda,, three by Claire Denis, several by the Belgium-born Chantal Akerman, and a very recent entry, Portrait de la jeune fille en feu (aka Portrait of a Lady on Fire) by Céline Sciamma. There’s no surprise that Italy is represented on the list by Lina Wertmūller, whose Seven Beauties made her the first woman ever to be nominated for a Best Director Oscar. Nor that Poland’s Agnieska Holland is recognized for the poignant Europa, Europa. It’s hard to accept the name of German filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, whose filmmaking talent here outweighs her use of cinema to glorify Adolf Hitler in documentaries like Triumph of the Will. (Women, like men, are not always as wise as they are talented.)

Though I haven’t seen every one of these films, I can hardly argue with the list’s #1 slot, which goes to New Zealand’s Jane Campion for her haunting feature, The Piano. Like Wertmūller, Campion was given a Best Director nod by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. She was not to nab an Oscar for directing, but won instead for her screenplay. There have been only three other female Oscar nominees for Best Director: Sofia Coppola for Lost in Translation, Kathryn Bigelow for The Hurt Locker (she actually won, possibly because her film had an intensely male focus), and Greta Gerwig for Lady Bird. All three are still active filmmakers, so maybe there’s hope that Coppola and Gerwig too will someday be among the chosen few. I also liked seeing on the BBC list names like that of Lisa Chodolenko, whose The Kids Are All Right was one of the standouts of 2010, Amy Heckerling (Fast Times at Ridgemont High), Kasi Lemmons (Eve’s Bayou).and Kimberley Peirce (Boys Don’t Cry). But I don’t know how the experts could have left out such talents as Nicole Holofcener (for the delightful Enough Said) and Allison Anders (Mi Vida Loca).

Then there’s an entry that continues to trouble me: Lana and Lilly Wachowski for 1999’s The Matrix. The Wachowskis, both transgender, were considered male when they shot this big-budget film. Did that fact help them get past the barriers that stop so many female directors in their tracks?

Published on January 03, 2020 10:19

December 31, 2019

In Memoriam: After the Parade Passes By

As that exasperating year 2019 wanes, it feels appropriate to look back on the famous movieland folks we’ve lost. TCM has put together a short but poignant video segment reminding us of some of the indelible faces and voices who now remain only in our movies and our dreams. I’ve written my own Beverly in Movieland tributes to some of these great performers: Doris Day, Peter Fonda, Valerie Harper, Albert Finney, Bibi Andersson, Machiko Kyo. And I’ve lamented the loss of outstanding filmmakers like John Singleton, D..A. Pennebaker, Franco Zeffirelli, and Stanley Donen. In the field of music (for the screen as well as for the stage and the concert hall) there have been several indelible passings: André Previn, Michel LeGrand, and Broadway’s Jerry Herman, the exuberant composer of Hello, Dolly and Funny Girl.

Of course deaths don’t stop when the memorial video is posted online. Jerry Herman, who died last Thursday at the age of 88, didn’t make the final cut. A recent edition of The Hollywood Reporter also lists a few passings that TCM overlooked. One was D.C. Fontana, the very first female writer on Star Trek. (In an era less politically correct than our own, women writers found it smart to conceal their gender by turning their given names into male-sounding initials.) Another was Carroll Spinney, the gentle, spritely puppeteer who impersonated Sesame Street’s Oscar the Grouch and wore the feathers of Big Bird for nearly half a-century. I was particularly moved when Karen Pendleton passed on in October at the age of 73. Pendleton, one of the original Mouseketeers, was a regular on The Mickey Mouse Club for its entire nine-year run. Though several of the Mouseketeers led tawdry adult lives, Pendleton was a major exception. After the show ended, she devoted herself to her education. When a 1983 car accident that damaged her spinal cord left her paralyzed from the waist down, she went back to college, earning a master’s degree in psychology. Putting her academic training to work, she served as a counselor at a shelter for abused women, while supporting the rights of the disabled by joining the board of the California Association of the Physically Handicapped. A life well lived, indeed.

I was sorry to read about the loss of masterful actors like Ron Leibman (so moving in Norma Rae) and Moonstruck’s Danny Aiello. And I shook my head ruefully at the passing of Jan-Michael Vincent, a talented action hero but one who cut his career short because of his personal weaknesses. (In later years he was reduced to appearing in Roger Corman war epics, like my own Beyond the Call of Duty, flying off to Manila to star in quickie flicks undermined by his drinking habits.)

But of courses the deaths that most moved me were those of celebrities with whom I’ve personally interacted. It seems like yesterday that I, as a writer of profiles for Performing Arts magazine, was welcomed at the home of the versatile character actor René Auberjonois, who lit up stage and screen with his eccentric portrayals. I will always think fondly of the late Dick Miller, my buddy in my New World Pictures days and years later a valuable source of information when I was researching my Corman biography. How wonderful that Dick inspired both the loyalty of some of Hollywood’s finest directors and an affectionate 2014 documentary (That Guy Dick Miller) summing up his long career And then there is good-guy Robert Forster, whose resonant baritone is—and always will be—on my answering machine. Hail and farewell. .

Published on December 31, 2019 09:01

December 27, 2019

Culver City: The Heart of Screenland Beats Again

Culver City, a small civic enclave in West Los Angeles, likes to call itself “The Heart of Screenland.” The legendary MGM Studios (which once used to boast that it had “more stars than there are in heaven”) occupied a central spot at the junction of Washington and Culver Boulevards. Back in the days of Irving Thalberg and Louis B. Mayer, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer was synonymous with glamour, and MGM’s mascot, Leo the Lion, was the king of the movieland jungle. Alas, by the time I moved into Culver City, the stars had largely gone elsewhere. With the decline of the studio system, MGM had sold off its fabled backlot, where Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz were filmed, to create a middle-class housing tract called Studio Estates. (You could live on street like Garland Drive, Hepburn Circle, or Astaire Avenue, each of them named after a Golden Age MGM notable.) What was left of the MGM lot—with its huge soundstages, star bungalows, and elaborate wardrobe facilities—was largely scooped up by a new Hollywood player from Japan, Sony Pictures.

Recently I took a tour, hosted by the ever-enterprising Los Angeles Conservancy, that focused on Culver City’s recent rebirth. Some of this involves ultra-cool modern architecture associated with the Southern California tech phenomenon called Silicon Beach. But in Downtown Culver City, near where the staid old Culver Hotel once housed a rowdy bunch of Munchkins who were appearing in The Wizard of Oz, old is meeting new in highly unexpected ways. It was a reminder to me that MGM has never been the only studio in town. Right down the road, in a stately white columned building that reminds onlookers of Scarlett O’Hara’s Tara, there’s a smaller studio that has also played a famous role in Hollywood history.

The Culver Studios Mansion was erected back in 1918 by silent film actor, director, and producer, Thomas Ince, who modeled it after George Washington’s Mt. Vernon. Ince didn’t enjoy his studio (which also included a 40-acre back lot) for long. In 1924, in celebration of his 44thbirthday, he boarded the yacht belonging to William Randolph Hearst for a pleasure cruise that also involved Charlie Chaplin and Hearst’s mistress, Marion Davies. After a dinner involving lots of champagne, he became severely ill, was carried off the yacht in Long Beach harbor, and died. Heart failure was the official cause, but persistent rumors tell a far different tale: that Hearst had shot Ince in the head, mistaking him for Chaplin whom he thought was having an affair with Davies.

After Ince’s death, his studio property was first occupied by Cecil B. DeMille, then by RKO, and by producer David O. Selznick, who featured the stately mansion in the opening credits for all of his films. (No, it was not used as Tara, but the burning of Atlanta in GWTW featured the bonfire made of old sets on the property.) In the early days of television the studio was purchased by Desilu, and used for such landmark TV series as The Andy Griffith Show. Today a mural featuring Lucy and Desi commemorates that period.

So what’s going on now? The studio site has been acquired by Amazon Studios, and an extensive remodel is taking place. Though the Mansion and some legendary star bungalows (including one where Gloria Swanson canoodled with Joseph Kennedy) have been carefully preserved, the lot is now dominated by massive construction equipment. That means offices, parking spaces (of course!) and such amenities as barbecue pits, along with modern facilities for turning out Hollywood-worthy content. High tech strikes again.

Published on December 27, 2019 10:00

December 24, 2019

A Fiddler on the Screen for Christmas: Sounds Crazy, No?

A few years back, I was invited to a local synagogue on Christmas Eve, to speak about my book, Seduced by Mrs. Robinson. The invitation was in line with the old saw about what Jews do on Christmas Eve. Traditionally, so it’s said, Jews eat Chinese food and go to a movie. So the very hip event planners at Santa Monica’s Kehillat Ma’arav had come up with an irresistible deal: a kosher Chinese buffet and a screening of The Graduate, with my talk as (I suppose) the dessert.

This year Christmas Eve just happens to fall on the 3rd night of Hanukkah. And what better time for L.A.’s Laemmle theatre chain to offer its very own Christmas eve tradition? The Laemmle family of film exhibitors come from a long line of proud Jews, dating all the way back to Universal Studios founder Carl Laemmle. (Aside from his fame as an early movie mogul, Carl was known in his day for saving hundreds of Jewish residents of his German birthplace from the Nazis) For the last dozen years, the homey local theatres in the Laemmle chain of independent cinemas have participated in a tradition of their own. But let the Laemmles describe it, via their website:

JOIN US TUESDAY, DEC. 24th for an alternative Christmas Eve. That's right - It's time for our 12th Annual, anything-goes Fiddler on the Roof Sing-a-Long!

Belt out your holiday spirit … or your holiday frustrations. Either way, you'll feel better as you croon along to all-time favorites like “TRADITION,” “IF I WERE A RICH MAN,” “TO LIFE,” “SUNRISE SUNSET,” “DO YOU LOVE ME?” and “ANATEVKA,” among many others.

The evening includes trivia, prizes, and by all means -- we encourage you to come in costume! Guaranteed fun for all?

At each venue, a guest host (a well-connected cantor or Jewish entertainer) is guaranteed to help attendees rock the shtetel. I personally can’t make it this year, but it sounds like great fun, and it’s also an opportunity to see once again on a big screen .a film that gets better with age. When it was first released in 1971, I compared it unfavorably to the bravura Broadway production, starring the larger-than-life Zero Mostel. When Norman Jewison (who jokes about not being Jewish, despite his name) was selected to direct the film version, he made clear that the cinematic rendition would be less fanciful, more realistic. Instead of Mostel, he went with a young-ish Israeli performer no one had heard of. His name was Topol, and he was funny, poignant, real, and totally masterful. His was one of eight Oscar nominations for the film, which danced off with three.

To see the film Fiddler on the Roof from another perspective, check out a 2019 feature-length documentary called Fiddler: A Miracle of Miracles. Based on Alisa Solomon’s fascinating book, it delves deeply into the backstory of the Broadway musical, then explores some ways in which Fiddler on the Roof has influenced audiences all over the world. Taking this one step farther, the documentary roams the globe, showing us glimpses of productions in Japan, Thailand, and the Netherlands. It then gives us a glimpse of the Yiddish-language version (directed by Joel Grey, the Oscar-winning son of Yiddish comic great Mickey Katz) that has ecently galvanized the New York theatre scene.. And there are lots of on-camera interviews with show biz folks ranging from Harvey Fierstein to Lin-Miranda, who appeared once upon a time in a junior high production. Miranda loves Fiddler so much that he staged a surprise rendition of one of its songs at his wedding reception. On Christmas eve, L’chaim to one and all!

Published on December 24, 2019 12:48

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers