Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 64

September 10, 2019

He to She: They Changed It At the Movies

Gender-bending seems to be the rule of the day. On cable television, there’s Pose, an exploration of what is called New York’s gender-nonconforming ballroom culture: it’s currently vying for six Emmy awards, including one for Billy Porter as lead actor in a dramatic series. In 2018, a Chilean film, Una mujer fantástica , won the Academy Award for best foreign language film. Its leading lady, Daniela Vega, made history that year as the first -ever transgender person to serve as a presenter on the Oscar stage.

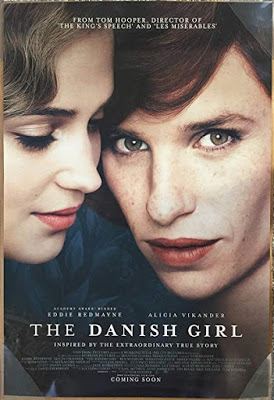

Recently I caught up with two film productions that tackle, with very different stylistics, the life of a man who chooses to live as a woman. The Danish Girl, from 2015, is semi-fictitious in its details but is based on the real-life Einar Magnus Andreas Wegener, a young painter who in 1920s Denmark evolved into a woman named Lili and underwent some of history’s first sex change operations. At the start of the film Einar (played by a totally engaging Eddie Redmayne) is married to a fellow artist named Gerda, a lively bohemian played by Alicia Vikander. As apparently happened for real, Einar first discovers the truth of his nature when asked by his wife to fill in for a missing model. Posing draped in a ballerina’s tights and tutu, he finds himself enthralled by the sensuous pleasures of female garb. This leads in the film to Gerda mischievously parading him at a posh art opening as Einar’s tall, shy cousin Lili. But the masquerade becomes all too real when another young man falls for Lili, and Einar becomes ever more convinced that he is meant to be female, even to the point of wanting to bear children.

There’s hardly a happy ending. But the actors are fully committed to their roles, managing to convince us that theirs is a beautiful love story, if a tragic one. The versatile Redmayne, who had previously persuaded Oscar voters that he was Stephen Hawking, remains credible and lovable whether dressed as a man or a woman. (His impishly secretive smile is essential in this regard). Alicia Vikander, as the woman who loves him too well to insist on keeping him, nabbed her own Oscar for her role. The music is lush; the muted but lovely scenery and costumes are to die for. I guess the film could be shrugged off as a weepie, but one beautifully executed in a Merchant-Ivory vein.

Then there’s Tangerine, which is a trans film of a different color. Indie filmmaker Sean Baker, who would go on to shoot The Florida Project two years later, got the film community’s attention when he shot this feature entirely on three iPhone 5s smartphones. No, the moviegoer isn’t required to watch this film on a tiny screen, though it will never be mistaken for Cinemascope. Tangerine tells a sordid but affecting slice-of-life story about a day in the life of an African-American transgender hooker named Sin-Dee Rella who plies her trade on the seedy streets of L.A. Just out of the slammer on Christmas Eve, she’s looking for the pimp who’s apparently cheating on her with a cisgender woman. Meanwhile her best buddy is trying to drum up business for a late-night singing gig, and a sad-sack immigrant Armenian cab driver is struggling to deal with his wife, his infant daughter, and his harridan of a mother-in-law. Somehow they all wind up in a late-night donut shop, where what happens is either very sad or very funny or both. In any case, it seems quite real: or about as real as L.A. on a sultry Christmas eve.

Published on September 10, 2019 12:31

September 5, 2019

Valerie Harper: Savory Ham on Rye?

Who could resist Valerie Harper? At the start of the 1970s, on the always hilarious Mary Tyler Moore Show, she was Rhoda Morgenstern, the best buddy whose self-deprecating wit and funky style made for a vivid counterpoint to the girl-next-door charm of Mary Richards,. Mary was of course played (by series star Mary Tyler Moore) as a bubbly Midwesterner, a would-be broadcast journalist cursed with the perennial desire to be nice. Her pal Rhoda, a window-dresser by trade, is a blunt New York transplant who bemoans the size of her hips (well, next to the reed-like Mary, anyone would look chubby) as well as her failures on the dating scene. Niceness—as opposed to datelessness—isn’t something Rhoda worries much about..

Part of Rhoda’s unique appeal is that, in a series set in Minneapolis, she’s at least a tiny bit East Coast ethnic. Not that her apparent Jewishness goes much beyond her name Still, she adds to Mary’s white-bread allure a nice slice of pumpernickel, or maybe even corn rye. So beloved was she on the Mary Tyler Moore Show that the show’s production company, headed by MTM’s husband Grant Tinker, got the bright idea that Rhoda should head her own series. He enlisted the same veteran comedy writers (James L. Brooks and Allan Burns) who’d given the Mary Tyler Moore cast such great things to say. The writers posited that now Rhoda has returned to her native Upper East Side, where she’s living with her parents Nancy Walker and Harold Gould. There’s a fair amount of Jewish shtik (much favored in that era, but slightly distasteful now – are you listening, Mrs. Maisel?), and Rhoda’s Mary Tyler Moore buddies drop in from Minneapolis to help her adjust. I even recall a direct comic steal from the famous opening of Mary Tyler Moore in which our Mary, ready for life in the big city, exuberantly flings her tam into the air. Rhoda tries this in Times Square, only to have the hat flop to the sidewalk. Oh well!

Rhoda lasted five years, so I wouldn’t consider it a disaster. But many of us who set viewership records watching Rhoda get married were bound to be disappointed. A domestically contented Rhoda was not the Rhoda we knew and loved. Ironically, it fell to her sidekick, the sister played by Julie Kavner, to channel all the insecurity that had helped us identify with Rhoda herself. Kavner, who for years has earned a nice paycheck as Marge Simpson, has a great adenoidal voice, and it was easy to accept her as a Rhoda in the making.

One personal story: when I was working for Roger Corman at New World Pictures, director Monte Hellman needed an actor to play the sidekick of Warren Oates in Cockfighter. Since I was helping with casting, he asked me to call in Richard Shull. I looked through the era’s casting bible, couldn’t locate a Richard Shull, but spotted the name Richard Schaal, which certainly sounded similar. I knew who he was: Valerie Harper’s spouse, and a veteran of improv theatre. So I booked him for an interview, and he showed up at our scruffy offices, very excited. Only to be told, alas, that he wasn’t the New York guy Monte had in mind. Rarely have I felt so sorry for a stranger: it was 1973, Dick was wed to one of TV’s brightest stars, and he clearly was desperate to show off his own talents. So it goes in Hollywood—no wonder the marriage didn’t last. And I’ve never stopped feeling a wee bit guilty.

Published on September 05, 2019 11:21

September 3, 2019

Fay Wray and Robert Riskin: Odd Couple? or Marriage Made in Movie Heaven?

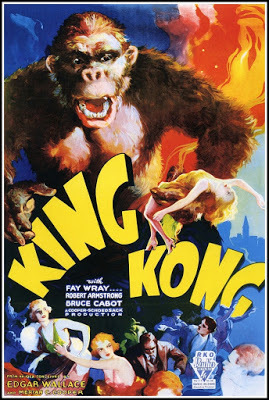

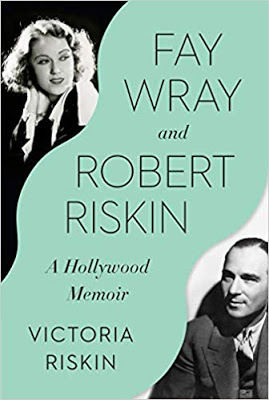

Not far from my Santa Monica home is the legendary McCabe’s, where serious folk musicians gather to jam as well as to stock up on guitar picks and such. The upstairs walls are lined with candid photos of the likes of Joni Mitchell and Arlo Guthrie. These luminaries and many others have performed on McCabe’s tiny stage, to the delight of rapturous crowds. But why, in this downhome music mecca, is there a prominent poster of Fay Wray, trembling in the arms of King Kong?

This mystery was finally solved when I met Victoria Riskin, psychotherapist, screenwriter, producer, and now the author of Fay Wray and Robert Riskin: A Hollywood Memoir. Victoria is the youngest of three children of an unlikely Tinseltown couple whose thirteen-year marriage was going strong until Riskin’s untimely death, at age 58, on September 20, 1955. Victoria’s brother Bob, two years her senior, is the longtime owner of McCabe’s. So it makes sense that one wall of the funky guitar shop pays tribute to a vibrant woman who treated life as a great adventure. I had always mentally lumped Fay Wray with the scream queens of Hollywood, those damsels in distress—the mainstays of B-movies—who were forever needing to be rescued. But Wray at the time she shot King Kong was a major Hollywood star who shared the screen with some of the industry’s most talented actors, including Gary Cooper, Ronald Colman, and Spencer Tracy. When a new project arose in 1933, she was told by director Merian C. Cooper she’d be playing opposite the tallest, darkest leading man in Hollywood. She immediately thought of Cary Grant, or perhaps Clark Gable. But ultimately she found Kong a very agreeable substitute for a Hollywood hunk. Years later, she confessed to a friend, “Every time I’m in New York, I say a little prayer when passing the Empire State Building. A good friend of mine died up there.”

Fay Wray came from pioneer stock. Hailing from an impoverished Mormon family, the plucky teenager boarded a train in Salt Lake City to try her luck in the movie biz. By contrast, Robert Riskin was the child of Jewish immigrants, raised on the mean streets of New York. He arrived in Hollywood by way of his skills as a playwright, soon connecting with director Frank Capra. Together they turned out some of the wittiest films of Hollywood’s Golden Age. On 1931’s Platinum Blonde, Riskin was credited solely as a dialogue writer, but his sparkling script for It Happened One Night (1934) won him a screenwriting Oscar. He also contributed the Riskin touch to such other Capra triumphs as Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, You Can’t Take It With You, and Meet John Doe. Sad but true that in later years Frank Capra became enamored of the auteur theory, and resisted attempts to credit his favorite screenwriter (and longtime close friend) of playing any part in his own success. Victoria remembers long after her father’s death, when the great director spoke before an appreciative crowd at the American Film Institute. During the question-and-answer period, he artfully dodged questions about working with screenwriters. Victoria was left to remember something her father had said twenty years earlier: “So little is known of the contribution that the screenwriter makes to the original story. He puts so much into it, blows up a slim idea into a finished product, and then is dismissed with the ignominious credit line—‘dialogue writer.’”

Wray and Riskin had different skills and very different backgrounds, but their marriage was rock-solid. In Hollywood (and elsewhere), that’s saying a lot.

Published on September 03, 2019 11:55

August 29, 2019

The Young Victoria: Royal Rebel

It’s not easy being queen. Nor, for that matter, making a film about the not-so-long-ago queen of a nation that’s very much connected to our own history. I became interested in Britain’s Queen Victoria when I recently toured Kensington Palace. No, I wasn’t invited to tea by Harry and Meghan. They do live in Kensington Palace, as do Prince William, Kate, and their brood. (Clearly, it’s a very big palace.) But the historic rooms of this London landmark have now been spruced up for tourists. I learned a lot about the lavish apartments of George II—ladies were admitted to inner-sanctum parties only if their dresses with sufficiently bouffant—and the far more austere ones of William and Mary. But the chief attraction is the childhood rooms of Queen Victoria, the centenary of whose birth is being celebrated this year.

The word “Victorian” is such a part of our language that we rarely stop to think about it. Queen Victoria, in our minds, is a plump old woman in severe black widow’s weeds, forever mourning the death of her consort decades before. We consider her prim to the point of stodginess, burdening her descendants with an obsolete moral code. But, as I learned at Kensington, Victoria was far more complicated than the dour widow we associate with the era that bears her name. Her father, the younger brother of King George IV, died when she was one year old. As her father’s brothers all lacked legitimate heirs (though there were illegitimate offspring aplenty), it quickly became clear that the young Victoria was in line to assume the throne of England. Her mother, a German princess, in tandem with the ambitious, domineering Sir John Conroy, kept her a virtual prisoner at Kensington. She was not allowed playmates or much in the way of intellectual stimulation; she shared a bedroom with her mother and -- when descending the stairs of the palace -- was required (even into her teens) to hold the hand of a lady-in-waiting. Sir John’s goal, if she were crowned before age eighteen, was for her mother to be declared regent, with himself as the power behind the throne.

Fortunately for English history, the elderly and ailing George IV survived until after Victoria had reached her eighteenth birthday. On June 20, 1837, she was awakened with the news that she had become Queen. Finally able to make her wishes known, she banished Conroy, freed herself from her mother’s grip, and started making her own decisions. Naturally, various factions tried to control her choice of a marriage partner. She was barely eighteen, extremely sheltered, and seemed easy to manipulate. A German branch of her family contrived to introduce her to Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, and she was immediately smitten. Happily, so was he. They corresponded for several years (she even sent him a fetching “secret portrait” of herself with her hair undone and shoulders bare), but she had become savvy enough to postpone matrimony until she was secure on the British throne. Finally she proposed marriage—that’s what queens get to do—and by all accounts their relationship was a constructive and loving one, producing nine children and some valuable social programs.

A 2009 British film, The Young Victoria, stars Emily Blunt as the headstrong and frankly sensuous (and charming) queen. I watched it with pleasure, since it reproduced so much I had learned at Kensington Palace. But IMDB lists multiple complaints of tiny historical inaccuracies, like an incorrect placement of the Order of the Garter. All those Anglophiles out there should really get a life.

Painted for Albert's Eyes Only

Painted for Albert's Eyes Only

Published on August 29, 2019 11:53

August 27, 2019

Ozu’s “Tokyo Story”: The Poetry of Everyday Life

After the close of World War II, the west discovered the charms of Japanese cinema. The hero of the era was the great Akira Kurosawa, whose lively blood-and-guts productions, like Yojimbo(1961) and Sanjuro (1962), meshed well with western sensibilities. In Kurosawa’s swashbuckling screen epics, Toshiro Mifune became an international star. It’s not surprising to learn that Kurosawa’s formative influence was American westerns. No wonder fans of the classic American action flick revere the Japanese master whose Seven Samurai (1954) was the source material for The Magnificent Seven.

Then there was Yasujiro Ozu, whose fifty-odd films were less prone to capture the imagination of western viewers. Ozu’s spare style and avoidance of on-screen theatrics give his movies a Zen-like simplicity that lacks obvious audience appeal. Yet film-lovers worldwide have discovered Ozu, seeing in his intensely Japanese subject matter a universality that is unexpected but profound.

Tokyo Story (1953) is Ozu’s acknowledged masterpiece. At first it’s not entirely obvious why this modest story is held in such high esteem, but a serious filmgoer who doesn’t expect fireworks is soon drawn into its orbit. The plot is simplicity itself: a long-married couple from the old seaside town of Onomichi travel to visit their married children in Tokyo. The children are not overtly unkind to their elderly parents, but their busy lives (as a doctor, as the owner of a hair salon) keep getting in the way, and it’s soon decided to pack the old couple off to a spa where rowdy fellow guests make their stay miserable. Only the widow of their second son, killed in World War II, interrupts her daily obligations to make time for them, for which they are genuinely grateful. The portrait of old age is touching (even though we discover they’re only in their sixties – yikes!), and we commiserate fully with them in gratitude for any scrap of kindness. There’s a melancholy ending to the story, which reinforces our sense of the passage of time and the evolution of family relationships. The characters may be Japanese to the core, but their situation is familiar, I think, to us all.

In keeping with his reputation as the most Japanese of Japanese filmmakers, Ozu’s film makes profound use of the sense of place. Though there’s little room (or budget, I suspect) for aesthetic flourishes, we quickly see the difference between little Onomichi (in Hiroshima prefecture) and the big metropolis. Onomichi is visually represented by traditional tile roofs, a quaint Buddhist temple, and a small boat plying its way across the local waters.. Every time the scene shifts to Tokyo, the screen is assaulted by belching smokestacks. The couple’s children, who wear western dress instead of traditional kimono, live in tightly packed urban dwellings, unfolding their futons every night. and packing them up in the morning to make for living space, however cramped.. Ozu favors a low-angle camera that barely moves, and his straight-on capturing of the life that goes on in and around shoji screens makes Japanese home architecture seem much like a stage set.

I learned to speak Japanese during my college years, and used it daily when I worked at Expo ’70 in Osaka. Tokyo Story made me profoundly nostalgic for Japanese linguistic formality and regional accents. Though any thoughtful person can appreciate this film, I feel lucky that the cultural nuances on screen (which doubtless would seem profoundly dated to a modern Japanese) did not pass me by. Moreover, I’ll long cherish the film’s depiction of the unstated but profound love between a pair who are no longer young.

Published on August 27, 2019 11:54

August 22, 2019

Some Separate Thoughts about “Separate Tables”

When I was a kid, I loved watching the Oscar broadcast, even when I was too young to have seen all the big films of the year. That’s why I remember David Niven (whom I’d loved as the veddy British Phileas Fogg in Around the World in Eighty Days) looking very pleased indeed when picking up his Oscar for Separate Tables. That 1958 film would have been far too serious for someone of my tender years—but I’ve long since overcome that hurdle. Watching Separate Tables recently, I was impressed by its theatricality, by its marvelous ensemble acting, and by the grown-up way it looks at human behavior. (No superheroes and supervillains here.) At the same time, I was struck by the ways its view of male/female relationships diverges from the attitudes of the #MeToo era.

Part of why Separate Tables originally intrigued me was its mysterious title: where were these tables, and why were they separate? The title refers to a residence hotel whose long-term occupants take all their meals in a common dining room, but are assigned their own permanent seats at individual tables. The arrangement—so very formal—seems distinctively British to me. Americans, I suspect, would just sit anywhere, changing their seats at whim. But the rigidity of expectations and social manners is, in a way, what Separate Tables is all about.

It started out as a hit play by British author Terence Rattigan. Opening in London in 1954, it was actually two one-act playlets, both set in the same modest hotel in Bournemouth, on the English coast. “Table by the Window” detailed the awkward encounter of a disgraced British politician with his ex-wife. “Table Number Seven” explored the relationship of a repressed spinster and an older man posing as Major Pollock, a decorated war hero. Artfully, the film version (directed by Delbert Mann) combines the two stories, which both unfold during a few tense days amid the ebb-and-flow of life in the hotel’s public and private rooms. Burt Lancaster’s production company, known for taking artistic chances, assembled a cast of British stage and screen stalwarts, but also made room for two Hollywood stars, Lancaster himself and the still-beautiful Rita Hayworth. They play the divorced couple, now convincingly transformed into Americans abroad, whose tragedy is that, despite a still-flaming passion, they bring out the worst in one another. Niven is marvelous as the well-meaning but deeply flawed little man who pretends to be heroic, and Deborah Kerr proves almost unrecognizable as a drab young woman still under her mother’s thumb. Others in the ensemble include Wendy Hiller (she too won an Oscar) as the brisk hotel manager who is forced to keep her own needs under wraps. [The film’s seven Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, also rightly saluted Charles Lang’s moody black-and-white cinematography and David Raksin’s evocative score.]

Lancaster and Hayworth are convincing in their mutual lust, and in the powerful emotional connection that sometimes tips over into violence. But it’s shocking to see Lancaster strike Hayworth, causing her to tumble down a staircase. After this powerfully-staged scene, a modern viewer would find it unthinkable that these two would end up together. There’s also (spoiler alert) the discovery that David Niven’s character has fled his home town after an arrest prompted by a physical assault on a woman in a darkened movie house. Most of his fellow boarders easily forgive this behavior, which in any case seems totally out of character for him. In an early draft, Major Pollock’s misdeed was a homosexual advance, which seems—to a modern sensibility—vastly more convincing.

Published on August 22, 2019 11:48

August 20, 2019

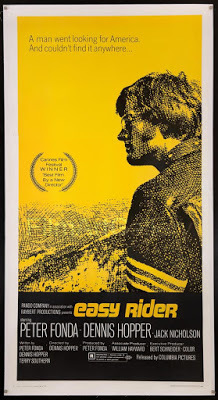

Peter Fonda, An Easy Rider Who Chose the Road Not Taken

The death of Peter Fonda seems like one more reminder that the Sixties are now long gone. I vividly recall going out to dinner, circa 1970, with my husband-to-be in a trendy bistro on the Sunset Strip. To us the back room, overlooking the lights of the city below, was the height of elegance. So it was a curious moment when some well-dressed young women started excitedly unrolling a huge poster. It was an almost-life-sized image of Fonda and Dennis Hopper, astride their choppers, decked out in their Easy Rider duds. That wasn’t a poster I’d want to display in my own home, but it seemed a fair encapsulation of what was in a lot of youthful minds as the Sixties faded away.

Peter Fonda, son of the iconic Henry, began his film career in the romantic comedy, Tammy and the Doctor (1963). But before Easy Rider (1969) made the tall, lanky Fonda a spokesman for the Counterculture, he had already become a Sixties icon as the chopper-riding Heavenly Blues in The Wild Angels (1966), Roger Corman’s gritty celebration of the Hells Angels motorcycle gang. (Sample dialogue: “We want to be free to ride our machines without being hassled by the Man! And we want to get loaded!”) Fonda was then an enthusiastic supporter of the drug scene. He helped the fundamentally strait-laced Corman shed his inhibitions by shoving a kilo of marijuana into Roger’s mailbox as a Christmas gift. And when Corman followed up the notoriety of The Wild Angels with an hallucinogenic LSD film (1967), The Trip, Fonda demanded that Roger do research by dropping acid himself. (Roger’s one and only LSD trip, which took place in California’s Big Sur, has become the basis for The Man with Kaleidoscope Eyes, a screenplay that Corman alumnus Joe Dante is still hoping to shoot.)

Peter Fonda described the genesis of Easy Rider in a 1969 issue of Take One magazine. Staying at a Canadian hotel for a motion-picture exhibitors’ convention, he happened to study a publicity shot of himself and Bruce Dern riding their choppers in The Wild Angels. Staring at the iconographic photo, Fonda got an idea: “Man, yeah, that’s the image . . . a dude who rides a silver bike and turns everybody on and rides right off again.” As the movie’s plot evolved in his head, he decided, “Let’s get to Mardi Gras in the film, great time, we’ll have a lot of free costumes and shit like that, a real Roger Corman number where we don’t have to pay.” Easy Rider was produced by Fonda in 1969. He and Dennis Hopper (a longtime friend who had been featured in The Trip) wrote the screenplay, along with novelist Terry Southern; the roles played by Fonda, Hopper, and Jack Nicholson were to make them all stars. Corman, aware of the developing project, tried to help get it AIP backing.

Sam Arkoff, the creative head of American International Pictures, has admitted that AIP was ready to invest $340,000 in Easy Rider, but balked at Hopper’s plan to direct the film himself. Arkoff and company believed that Roger Corman, with his low-budget track record, would be the best man for the job. Hopper, of course, proved them wrong. But while Corman had no part in the finished film, it very much reflects his spirit and style.

It was Fonda and Hopper, though, who got the kudos. They shared a screenplay Oscar for Easy Rider,and Fonda also collected an acting nod for his sensitive 1997 role in Ulee’s Gold. He’ll be missed.

Published on August 20, 2019 11:42

Peter Fonda, An Easy Rider Who Chose the Path Not Taken

The death of Peter Fonda seems like one more reminder that the Sixties are now long gone. I vividly recall going out to dinner, circa 1970, with my husband-to-be in a trendy bistro on the Sunset Strip. To us the back room, overlooking the lights of the city below, was the height of elegance. So it was a curious moment when some well-dressed young women started excitedly unrolling a huge poster. It was an almost-life-sized image of Fonda and Dennis Hopper, astride their choppers, decked out in their Easy Rider duds. That wasn’t a poster I’d want to display in my own home, but it seemed a fair encapsulation of what was in a lot of youthful minds as the Sixties faded away.

Peter Fonda, son of the iconic Henry, began his film career in the romantic comedy, Tammy and the Doctor (1963). But before Easy Rider (1969) made the tall, lanky Fonda a spokesman for the Counterculture, he had already become a Sixties icon as the chopper-riding Heavenly Blues in The Wild Angels (1966), Roger Corman’s gritty celebration of the Hells Angels motorcycle gang. (Sample dialogue: “We want to be free to ride our machines without being hassled by the Man! And we want to get loaded!”) Fonda was then an enthusiastic supporter of the drug scene. He helped the fundamentally strait-laced Corman shed his inhibitions by shoving a kilo of marijuana into Roger’s mailbox as a Christmas gift. And when Corman followed up the notoriety of The Wild Angels with an hallucinogenic LSD film (1967), The Trip, Fonda demanded that Roger do research by dropping acid himself. (Roger’s one and only LSD trip, which took place in California’s Big Sur, has become the basis for The Man with Kaleidoscope Eyes, a screenplay that Corman alumnus Joe Dante is still hoping to shoot.)

Peter Fonda described the genesis of Easy Rider in a 1969 issue of Take One magazine. Staying at a Canadian hotel for a motion-picture exhibitors’ convention, he happened to study a publicity shot of himself and Bruce Dern riding their choppers in The Wild Angels. Staring at the iconographic photo, Fonda got an idea: “Man, yeah, that’s the image . . . a dude who rides a silver bike and turns everybody on and rides right off again.” As the movie’s plot evolved in his head, he decided, “Let’s get to Mardi Gras in the film, great time, we’ll have a lot of free costumes and shit like that, a real Roger Corman number where we don’t have to pay.” Easy Rider was produced by Fonda in 1969. He and Dennis Hopper (a longtime friend who had been featured in The Trip) wrote the screenplay, along with novelist Terry Southern; the roles played by Fonda, Hopper, and Jack Nicholson were to make them all stars. Corman, aware of the developing project, tried to help get it AIP backing.

Sam Arkoff, the creative head of American International Pictures, has admitted that AIP was ready to invest $340,000 in Easy Rider, but balked at Hopper’s plan to direct the film himself. Arkoff and company believed that Roger Corman, with his low-budget track record, would be the best man for the job. Hopper, of course, proved them wrong. But while Corman had no part in the finished film, it very much reflects his spirit and style.

It was Fonda and Hopper, though, who got the kudos. They shared a screenplay Oscar for Easy Rider,and Fonda also collected an acting nod for his sensitive 1997 role in Ulee’s Gold. He’ll be missed.

Published on August 20, 2019 11:42

August 15, 2019

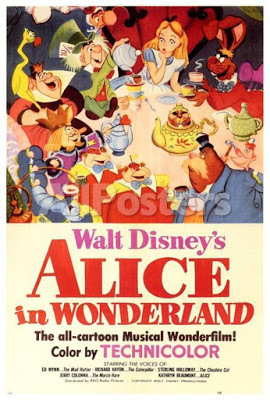

Go Ask Alice (about Wonderland)

Oxford, England may have recently gone crazy for Harry Potter, but another literary figure connected with this charming college town has a much longer pedigree. It was back in 1865 that an Oxford mathematician named Charles Lutwidge Dodgson published, under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll, a small book called Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The story of a little girl named Alice who slips down a rabbit-hole and meets a number of outlandish creatures (a caterpillar smoking a hookah, a totally mad Hatter, the dangerous Queen of Hearts) evolved out of the tales he told three little girls as they rowed up the River Isis from Oxford to the village of Godstow, five miles away. The girls were the daughters of Henry Liddell, dean of Oxford’s Christ Church College. (There were ten little Liddells in all, of whom ten-year-old Alice was the fourth.) After the boat trip, Alice begged Dodgson to write down the marvelous yarn he’d spun, He borrowed her name for his heroine, and dedicated the published book to her.

Oxford, England may have recently gone crazy for Harry Potter, but another literary figure connected with this charming college town has a much longer pedigree. It was back in 1865 that an Oxford mathematician named Charles Lutwidge Dodgson published, under the pseudonym Lewis Carroll, a small book called Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The story of a little girl named Alice who slips down a rabbit-hole and meets a number of outlandish creatures (a caterpillar smoking a hookah, a totally mad Hatter, the dangerous Queen of Hearts) evolved out of the tales he told three little girls as they rowed up the River Isis from Oxford to the village of Godstow, five miles away. The girls were the daughters of Henry Liddell, dean of Oxford’s Christ Church College. (There were ten little Liddells in all, of whom ten-year-old Alice was the fourth.) After the boat trip, Alice begged Dodgson to write down the marvelous yarn he’d spun, He borrowed her name for his heroine, and dedicated the published book to her.Today Dodgson and Alice Liddell are honored by Christ Church College with a special stained glass “Alice window.” It can be found high on the wall of the formal dining hall that was once the seat of Parliament during England’s seventeenth-century Civil War. At the center of one panel is a portrait of the actual Alice. Surprise! Instead of the long, straggly blonde hair of Tenniel’s famous illustrations, she wears a neat brown bob. Other panels include memorable images of familiar “Alice” characters. One is the White Rabbit, clutching his pocket watch. Legend has it that this rabbit, forever anxious about being on time for some very important date, is Dodgson’s comic portrait of Alice’s own father, who was known to be continually checking his timepiece. .

There’s one more Oxford place that provides a link to Alice in Wonderland. The venerable Oxford Museum of Natural History, founded in the Victorian era, contains the world’s best-preserved remains of the long-extinct dodo. There’s not much to see, merely the head and foot of a single bird. But the museum also displays a 1651 painting of a dodo by a Flemish artist, and it’s probable that Dodgson, a frequent museum visitor, used this as the basis for his wonderland dodo. Today display cases honor Alice as well as the dodo, showing off a taxidermied dormouse and even providing a stuffed white rabbit with his own tiny pocket watch.

It goes without saying that Hollywood has always loved the Alice stories. Back in 1933, Paramount Pictures introduced an elaborate black & white version, featuring such stars as Gary Cooper as the White Knight, Edna May Oliver as the Red Queen, Cary Grant as the Mock Turtle, and W.C. Fields as Humpty-Dumpty. Disney’s inevitable animated version, from 1951, of course favored the sweet over the scary side of the story, emphasizing how it takes place (in the words of one of the film’s songs) all on a golden afternoon. In 2010, director Tim Burton took the opposite tack. Updating Alice into a nineteen-year-old (Mia Wasikowska) on the brink of marriage to a dunce of a nobleman, he returns her to a phantasmagoric 3-D Wonderland where she must join forces with an outrageous Mad Hatter (Johnny Depp) to defeat the villainous Red Queen (an eye-popping Helena Bonham Carter)and her Jabberwocky, thus returning the White Queen (Anne Hathaway) to her throne. I admit I’ve only seen the trailer for this film, but that was enough to steer me away from Burton’s hectic, exhausting take on what Lewis Carroll wrought on a golden afternoon in Oxfordshire.

It goes without saying that Hollywood has always loved the Alice stories. Back in 1933, Paramount Pictures introduced an elaborate black & white version, featuring such stars as Gary Cooper as the White Knight, Edna May Oliver as the Red Queen, Cary Grant as the Mock Turtle, and W.C. Fields as Humpty-Dumpty. Disney’s inevitable animated version, from 1951, of course favored the sweet over the scary side of the story, emphasizing how it takes place (in the words of one of the film’s songs) all on a golden afternoon. In 2010, director Tim Burton took the opposite tack. Updating Alice into a nineteen-year-old (Mia Wasikowska) on the brink of marriage to a dunce of a nobleman, he returns her to a phantasmagoric 3-D Wonderland where she must join forces with an outrageous Mad Hatter (Johnny Depp) to defeat the villainous Red Queen (an eye-popping Helena Bonham Carter)and her Jabberwocky, thus returning the White Queen (Anne Hathaway) to her throne. I admit I’ve only seen the trailer for this film, but that was enough to steer me away from Burton’s hectic, exhausting take on what Lewis Carroll wrought on a golden afternoon in Oxfordshire.

Alice is in the top left panel

Alice is in the top left panel

Published on August 15, 2019 10:27

August 13, 2019

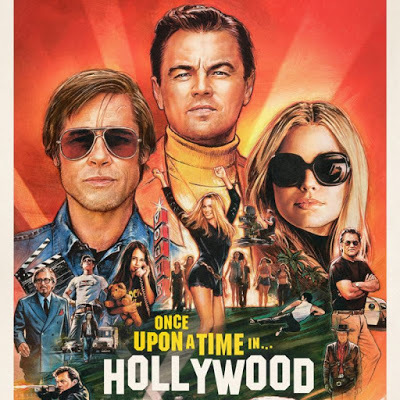

Tarantino’s Bedtime Story: Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood

When I think of the Tate-La Bianca murders, which made headlines fifty years ago this month, I remember first of all how scary L.A. suddenly seemed after news broke of the brutal murders on Cielo Drive. That feeling was reinforced when a student told me he’d grown up in the Los Feliz neighborhood where supermarket executive Leno La Bianca lived with his wife Rosemary. Not movie stars or socialites, they were the kind of homey middle-class people who gave special holiday treats to all the neighborhood kids. That didn’t stop them, alas, from being butchered by Charles Manson’s young thugs. No Angeleno, I quickly decided, was safe from a home invasion by a crazed hippie with something to prove.

Leave it to Quentin Tarantino to take us back to that terrible time and put his own spin on what happened. Tarantino has a genius for making L.A. look both beautiful and deadly. His camera sweeps down Hollywood Boulevard and the Sunset Strip, capturing the sizzling nightspots I recall from the past, like the young-oriented discotheque known as Pandora’s Box. He films his cast in restaurants I’ve known forever, including the clubby Musso and Frank and the kitschy Mexican eatery called El Coyote, in which the real Sharon Tate and her friends apparently had their last margaritas. Everywhere, in Tarantino’s L.A., there are movie houses, like the classic Village and Bruin, where the movie’s Sharon Tate (Margot Robbie) drops in to watch herself on screen in a Dean Martin spy flick, The Wrecking Crew. We also zip past lesser theatres, as well as movie billboards and posters advertising such dreck of the era as Three in the Attic and Joanna. (I suffered through both while serving as a film critic for the UCLA Daily Bruin.) The airwaves are flooded with music I remember well—“Mrs. Robinson” and Joni Mitchell’s “The Circle Game”—along with promos for the teen-oriented KHJ.

Tarantino’s film is well named, and not just because it seems to be an homage to Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America. His central subject in his best films is perhaps the making of stories. So it’s appropriate that his take on the Manson murders is far less interested in the killers and in victim Sharon Tate (who appears mostly as a beautiful icon) than in her fictional next-door neighbor, an aging actor struggling to move beyond his TV role in something called Bounty Hunter in order to make use of his genuine but sometimes tortured talent. As played by Leonardo Di Caprio, Rick Dalton is stuck in hackneyed bad-guy roles, a fact he deals with by drinking much too much. Still, he’s a celebrity, one whom everyone else (including the Manson gang) regards with awe for the simple reason that they’ve seen him on their TV screens.

Movie and TV stars, of course, do a lot of shedding of pretend blood. They also do a lot of fighting: even Tate is shown, at that Bruin Theatre screening, in a martial-arts cat-fight scene battling co-star Nancy Kwan in The Wrecking Crew. So it makes sense that playing opposite Di Caprio in Tarantino’s film is Brad Pitt as his stunt double, a guy quite used to getting physical, when he’s not cooking up his pathetic Kraft Mac-and-Cheese dinners in his sad little flat. Movie violence is faked, but Pitt’s character is quite good (possibly too good) at the real thing, which is how the Di Caprio/Pitt story and that of Sharon Tate happen to overlap. In ways, I can’t help saying, that might surprise you before the lights come up.

Published on August 13, 2019 12:05

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers