Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 61

December 19, 2019

The Cats Came Back (Caterwauling at the Movies)

I’m not exactly a cat person. Still, I admit I teared up when Holly Golightly (as played by Audrey Hepburn) rescued her sometimes-cat from a downpour at the end of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. I’ve liked other movie cats too, including Pyewacket , the sleek Siamese who was Kim Novak’s kindred spirit in the long-ago Bell, Book, and Candle. And it was hard to resist the frisson of watching Marlon Brando stroke a tabby while contemplating nefarious deeds in The Godfather.

My new friend Léon Bing, who modeled for the fashion world’s enfant terrible, Rudi Gernreich, and then wrote the bestselling Do or Die, has a particularly striking association with cats. As an aspiring model in New York City, she had to invent for herself a distinctive runway style. She had managed to rent a tiny but charming Park Avenue apartment, up only two flights of stairs. With time on her hands, she took to watching TV, and at one point the Movie of the Week was a sultry Southern-fried thriller, A Walk on the Wild Side. This 1962 drama, directed by Edward Dmytryk from a Nelson Algren novel, starred Laurence Harvey and Capucine, along with Jane Fonda, in one of her very first roles, as a young bordello recruit. It was possibly the name of Fonda’s character (Kitty) as well as all the film’s cat-house references that inspired the opening title sequence, the work of the great Saul Bass. While Elmer Bernstein’s music throbs on the soundtrack, a black cat prowls in dramatic closeup through the streets and alleys of New Orleans. As the music heightens you just know danger is lurking around every corner. And then it strikes. For Léon Bing, this footage—which she watched over and over—was total inspiration. She learned to slink through fashion shows like that dangerous cat, and the result was a long, successful career.

All this is by way of saying that I’m not so sure I’m enthralled by the prospect of seeing Cats on screen. The Andrew Lloyd Webber stage hit, set to charmingly whimsical poems by none other than T.S. Eliot, began its decades-long Broadway run in 1982. It ran so long (18 years at the Winter Garden Theatre) that it inspired an advertising slogan: “Cats, Now and Forever.” The vagueness of that slogan hints that Cats is not about anything much. Humans dressed as furry felines cavort about the stage, performing all sorts of colorful specialty numbers. What suspense there is involves which cat will be chosen by wise old Deuteronomy for a sort of cat-reincarnation. Of course the prize goes to the cat who’s the most bedraggled and sings the show’s most poignant power-ballad. And you surely remember what that’s called.

I don’t mean to sneer. Years ago, when Cats came to L.A.’s old Shubert Theatre, I had one of my favorite assignments for the Los Angeles Times¸ describing everything that happens at a big-time playhouse before the curtain goes up. So I watched stagehands preparing the set while ushers stuffed programs and actors stroked on their elaborate makeup. As a reward, I got to return with my six-year-old son, for whom this was a first-ever theatre outing. I had firmly lectured him on good behavior. But then—in the middle of a musical number!—a well-known local TV personality squeezed into my row with his young daughter. Instead of taking the empty seat next to me, she STOOD on his lap, and proceeded to give those around her a loud running commentary on the show. That was one kitten I would gladly have thrown down a well.

Published on December 19, 2019 11:49

December 17, 2019

The Terminal Life of Harvey Milk

I’m just back from San Francisco, famous as the place where Kim Novak’s Madeleine mesmerizes James Stewart’s Scottie in Vertigo, and where Steve McQueen chases bad guys through the winding city streets in Bullitt. San Francisco’s foggy hills and gingerbread Victorians seem made for movies that walk on the dark side, everything from film noir masterpieces like The Maltese Falcon and Out of the Past to psychological thrillers (among them Basic Instinct and Pacific Heights) 50 years later. But San Francisco has also been the setting for its share of amiable comedies, including Time After Time, in which a time machine sends H.G. Wells to the modern-day city once lovingly known as Baghdad by the Bay.

Though movies featuring San Francisco tend toward fantasy—of either the grim or the sunny sort—the film that lodged in my mind throughout my visit is both realistic and deeply heartfelt. Milk (released in 2008) explores the life of a real San Francisco icon, politician and gay rights activist Harvey Milk. The film, written by Dustin Lance Black and directed by Gus Van Sant, captures the rambunctious public spirit so typical of San Francisco, where residents are quick to celebrate the city as well as their own place within its complex social fabric. The focus, of course, is on Milk, winningly played by Sean Penn, as a camera-shop owner and would-be politician who in 1978 rises to become the first openly gay person ever elected to public office in California. As a member of San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors, Milk champions the rights of gays and other minority communities, while also showing his sympathies for the working-class in general. His forthright leadership helps to defeat a statewide ballot meeaure, the so-called Briggs Initiative, that would have banned any gay person from working within the California public school system.

Milk may be popular with open-minded San Franciscans, but he makes a dangerous enemy in fellow supervisor Dan White, a former fire-fighter with a conservative outlook. On November 27, 1978, White (played by Josh Brolin) shocks the world by entering City Hall and shooting Milk and Mayor George Moscone in their offices, killing them both. (It was Dianne Feinstein, then a supervisor and now a powerful member of the U.S. Senate, who was charged with leading San Francisco in the aftermath of those tragic days.) Though White notoriously used his addiction to junk food (the so-called Twinkie defense) to secure a light sentence, the film ends on a more hopeful note, with thousands of San Franciscans staging a candlelight vigil in memory of their fallen leaders.

In remembrance of Mayor Moscone, San Francisco erected a majestic conference center, one that has transformed the neighborhood below Market Street into a thriving cultural zone. It went up in 1981, and has undergone major expansions since. Many years passed before a building was named for Harvey Milk. But now the new Terminal 1 at San Francisco International Airport has been dedicated in his honor. I’m aware of airport facilities named after politicians, but I’ve never before seen this kind of large-scale homage to the life and career of a recently deceased local hero. In Terminal 1, huge walls are covered with Milk tributes: childhood photos, campaign posters, blow-ups of newspaper clippings, screaming banner headlines referencing his life and death.

Sean Penn nabbed an Oscar for playing Harvey Milk, and the film received 8 major nominations in all. It’s a fitting tribute to a fine American, but I’m glad airline passengers in 2020 will have a more visible reminder of the man we all lost.

Published on December 17, 2019 13:33

December 13, 2019

Safety Last on Friday the 13th

Downtown L.A. has long been a place for movies. The Downtown avenue known as Broadway was once lined by fabulous movie palaces, at which the beautiful people would congregate to see motion pictures in luxurious surroundings. (Those surroundings are much seedier today, but some of the theatres—like the Orpheum—still exist, and play host to special screenings.) And, in the days when the motion picture industry was new, Downtown was often used as a backdrop for Laurel and Hardy pie fights and for Harold Lloyd dangling off the side of an office building in Safety Last! In more recent years, even though so much production has moved to right-to-work states and Third-World countries (not to mention Canada), Downtown still has allure for filmmakers. Films like Drive and a staggering number of commercials for cars, trucks, and other vehicles have made use of Downtown thoroughfares. 500 Days of Summer showed off the romantic side of what hipsters now call DTLA.

I recently took an “above the skyline” tour of DTLA, sponsored by the always-reliable Los Angeles Conservancy. This particular tour focused on the high-rises that shoot up above and around L.A.’s old Bunker Hill neighborhood. As a group led by a gifted docent armed with plenty of photos of what used to be, we mourned the loss of the spectacular old Atlantic Richfield tower and cheered for the adaptive reuse of the Superior Oil Company headquarters into the charmingly eccentric Standard Hotel, whose upside-down sign is a new DTLA landmark. But the climax of our tour was a visit to the U.S. Bank Tower. Its construction, completed in 1989, led in a circuitous way to the saving of the grand old Los Angeles Central Library, which had been severely damaged by an arson fire and was dangerously close to being torn down. The backers of what was then called the Library Tower proposed to lease air rights above the library, which allowed for the building of a 72-story post-modern edifice, while giving the library the funds it needed for a major expansion campaign.

That 72-story tower, for many year’s L.A.’s tallest, is now owned by a Singaporean consortium, which has transformed its top floors and viewing desk into a genuine tourist attraction, the Oue SkySpace.. Along with spectacular views the SkySpace offers a multimedia primer on all the wonders L.A. has to offer. You can photograph yourself being accosted by paparazzi at a glamorous movie premiere, or pose high above the lights of the City of Angels with angelic wings extending from your shoulders. There are vivid displays of L.A.’s sports heroes, and of the iconic record albums (like The Doors and the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds) recorded locally to capture the L.A. vibe. Above all, there are nods to many of the movies set in SoCal: everything from the The Player to Straight Outta Compton, from The Big Lebowski to Crash. L.A. as seen in the movies is a place for romance and fun (The Graduate, L.A. Story), but also the grit and grime of urban life (Nightcrawler, Jackie Brown). It contains both the sadness of Chinatown and the derring-do of Die Hard, as well as the blend of horror and fantasy captured by Tarantino in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. And, of course—with its fires, quakes, and mudslides—it offers great possibilities for disaster flicks.

One of the stranger offerings at the SkySpace is an indoor/outdoor slide that slaloms you down a floor. It’s a great quick way to admire the view, and to remind you that L.A. is slide country, in more ways than one.

Beverly with Angel Wings

Beverly with Angel Wings View from Oue SkySpace

View from Oue SkySpace

Published on December 13, 2019 11:20

December 10, 2019

Marriage Story: The Sun Comes Up, I Think About You

Stephen Sondheim, composer/lyricist of arcane but wonderful Broadway musicals, is certainly having a moment at the movies. In the delightful Knives Out, Daniel Craig as Southern-fried detective Benoit Blanc casually warbles “Losing My Mind” from Sondheim’s Follies. It’s an odd, unlikely plot detail, but one that seems – upon reflection – to provide a whimsical clue to the film’s ending. Then there’s Noah Baumbach’s masterful Marriage Story. Writer/director Baumbach, whose previous credits include The Squid and the Whale, would seem to be the poet of dissolving marriages. He approaches the story of Charlie and Nicole Barber with even-handed but compassionate restraint. It’s a film that’s deeply moving, disturbing, but still somehow hopeful.

Sondheim songs come into Marriage Story late in the game, providing a pivot from the marital spat that’s the absolute nadir of the crumbling relationship into at least a guarded optimism. The husband and wife in question are both show folks (he a much-honored avant-garde stage director, she an actress blessed with star quality), and so it’s perhaps not surprising to see them stand up and perform in public. Scarlett Johansson, as Nicole, joins Julie Hagerty and Merritt Wever in a spirited off-the-cuff rendition of Sondheim”s perky “You Can Drive a Person Crazy,” from Company. It’s a sign, perhaps, that Nicole has moved past the anger she’s felt toward her ex-spouse for thwarting her own professional dreams. Immediately thereafter, on the other side of the continent, Adam Driver’s Charlie rises from a table at a local watering hole and delivers a heartfelt rendition of the plaintive but affirmative “Being Alive,” the climactic solo from the same show. He’s still hurting, we know, but he’ll move on.

Charlie and Nicole at first both claim to want a no-fault divorce, one that will allow them to separate firmly but gracefully, while still remaining friends. That’s, of course, before their lawyers get into the act. The legal profession does not come off well in these proceedings. The divorce attorneys (Laura Dern for her, first Alan Alda and then Ray Liotta for him) reduce a relationship into a pitched battle. In angling for their clients to emerge victorious, they twist every quirk and misstep into an indication of the other side’s culpability. Of course it quickly gets ugly.

The reason for lawyering up has everything to do with the one person who has no say in the matter, Charlie and Nicole’s eight-year-old son. Nicole wants young Henry with her in L.A., where she’s returning to her roots by starring in a TV series. Charlie insists Henry belongs where he’s always been, in New York City. In this, Marriage Story makes a fascinating contrast to an earlier award-winning film about a custody battle,1979’s Kramer vs. Kramer. In that New York-based film, a mother who feels stifled by domestic life suddenly decamps for the west coast, leaving her husband to cope single-handed with young Billy. The focus of Kramer vs. Kramer is how that father, a standard busy-young-exec type played by Dustin Hoffman, learns to expand his life to take over full-time parenting chores. Just when he’s been transformed by his new responsibilities, the wife (newcomer Meryl Streep) re-appears, suing for custody on the grounds that as mother she deserves to be the custodial parent.

Marriage Story has a more complex, and doubtless more modern, view of a father’s role. Charlie is a man who’s always loved tending to the needs of his son. He doesn’t have to be taught about fatherhood. The question is: can both he and Nicole remain active parents without striking a kind of Solomonic bargain?

Published on December 10, 2019 13:07

December 6, 2019

Dancing on Eggshells with "The Irishman"

Martin Scorsese, perhaps the most famous alumnus of the Roger Corman School of Film, won fame by chronicling society’s underbelly in hard-hitting dramas that featured guns, wiseguys, and lethal vendettas. Though he has made out-of-character contemplative work like Kundun and The Age of Innocence, as well as the charming family film Hugo, it’s still the gangsters movies that seal his reputation. No one is better than Scorsese at capturing the mania of a mind run amok with a sense of its own power.

But I’ve got to say: despite all the critical acclaim for his newest movie outing, I didn’t really fall for The Irishman. Whereas top reviewers in places like the New York Times saluted this film as a brilliant example of filmmaking craft, I had a tough time sitting through 3 ½ hours of meandering storytelling featuring a huge cast of characters I couldn’t entirely follow. (It’s hard to overlook the presence of Scorsese favorite Harvey Keitel in any movie, but I’m still trying to figure out when exactly – as mobster Angelo Bruno – Keitel showed up in this one.)

That’s not to say there’s nothing to appreciate in The Irishman. It’s a film that’s beautifully shot and full of memorable moments. Like two mob wives, dressed to the tens in garish fashions from the 1970s, who can’t be in a car for more than fifteen minutes before wanting to stop for a cigarette break. Or a rival union leader who royally pisses off the fastidious Jimmy Hoffa by showing up to a Miami meeting late, and wearing Bermuda shorts. And of course there’s the central triangle of stellar performances by Al Pacino as Hoffa, Joe Pesci as the quietly dangerous Russell Bufalino, and star/producer Robert De Niro as title character Frank Sheeran, he who (in gangster lingo) “paints houses.” As he boasts to Hoffa in a get-acquainted phone call, Frank also does some carpentry on the side.

De Niro’s Irishman moves through the film as the confident, quietly competent right-hand man to various marginal types. As an actor, he finds his biggest challenge in playing the elderly Frank Sheeran, who’s outlived everyone who matters in his world and is now leading a glum existence in a nursing home. There he’s reduced to looking for solace within religious ritual. His family is gone, and the fruits of his years of loyalty have turned out to be bitter indeed.

For the price of loyalty turns out to be a major theme in The Irishman. I don’t think it’s accidental that the film has a lot to say about matters affecting the current state of our country. As Hoffa’s decades-long story unfolds, we are reminded from time to time about the parallel doings within the nation at large. Like, for instance, the assassination of President Kennedy, seen by this film’s characters via a TV screen in a barroom. Just like mob bosses, it seems, presidents can be bumped off, leaving behind a trail of questions that can’t be answered. Of course JFK’s death occurred back in 1963. But the film seems current in its fascination with power-brokers, and yes-men, and with those whose high status depends on them. As played with manic energy by Pacino, Hoffa is a megalomaniac who seems all too familiar. Alternately domineering and sentimental, he is convinced that no one but he can be the legitimate voice of the Teamsters Union. Demanding fealty of everyone around him, he mistakes it for love. Too bad for Hoffa that the world turns out to be not quite the place he has imagined. We still don’t know what really happened.

Published on December 06, 2019 13:49

Dancing on Eggshells with The Irishman

Martin Scorsese, perhaps the most famous alumnus of the Roger Corman School of Film, won fame by chronicling society’s underbelly in hard-hitting dramas that featured guns, wiseguys, and lethal vendettas. Though he has made out-of-character contemplative work like Kundun and The Age of Innocence, as well as the charming family film Hugo, it’s still the gangsters movies that seal his reputation. No one is better than Scorsese at capturing the mania of a mind run amok with a sense of its own power.

But I’ve got to say: despite all the critical acclaim for his newest movie outing, I didn’t really fall for The Irishman. Whereas top reviewers in places like the New York Times saluted this film as a brilliant example of filmmaking craft, I had a tough time sitting through 3 ½ hours of meandering storytelling featuring a huge cast of characters I couldn’t entirely follow. (It’s hard to overlook the presence of Scorsese favorite Harvey Keitel in any movie, but I’m still trying to figure out when exactly – as mobster Angelo Bruno – Keitel showed up in this one.)

That’s not to say there’s nothing to appreciate in The Irishman. It’s a film that’s beautifully shot and full of memorable moments. Like two mob wives, dressed to the tens in garish fashions from the 1970s, who can’t be in a car for more than fifteen minutes before wanting to stop for a cigarette break. Or a rival union leader who royally pisses off the fastidious Jimmy Hoffa by showing up to a Miami meeting late, and wearing Bermuda shorts. And of course there’s the central triangle of stellar performances by Al Pacino as Hoffa, Joe Pesci as the quietly dangerous Russell Bufalino, and star/producer Robert De Niro as title character Frank Sheeran, he who (in gangster lingo) “paints houses.” As he boasts to Hoffa in a get-acquainted phone call, Frank also does some carpentry on the side.

De Niro’s Irishman moves through the film as the confident, quietly competent right-hand man to various marginal types. As an actor, he finds his biggest challenge in playing the elderly Frank Sheeran, who’s outlived everyone who matters in his world and is now leading a glum existence in a nursing home. There he’s reduced to looking for solace within religious ritual. His family is gone, and the fruits of his years of loyalty have turned out to be bitter indeed.

For the price of loyalty turns out to be a major theme in The Irishman. I don’t think it’s accidental that the film has a lot to say about matters affecting the current state of our country. As Hoffa’s decades-long story unfolds, we are reminded from time to time about the parallel doings within the nation at large. Like, for instance, the assassination of President Kennedy, seen by this film’s characters via a TV screen in a barroom. Just like mob bosses, it seems, presidents can be bumped off, leaving behind a trail of questions that can’t be answered. Of course JFK’s death occurred back in 1963. But the film seems current in its fascination with power-brokers, and yes-men, and with those whose high status depends on them. As played with manic energy by Pacino, Hoffa is a megalomaniac who seems all too familiar. Alternately domineering and sentimental, he is convinced that no one but he can be the legitimate voice of the Teamsters Union. Demanding fealty of everyone around him, he mistakes it for love. Too bad for Hoffa that the world turns out to be not quite the place he has imagined. We still don’t know what really happened.

Published on December 06, 2019 13:49

December 3, 2019

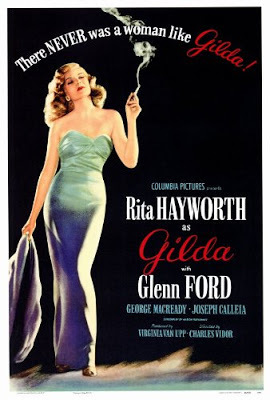

Going to Bed with Gilda in London’s Notting Hill

While out of town over the Thanksgiving holiday, I flicked on my motel-room TV set and found myself watching a charming Richard Curtis confection from 1999, Notting Hill. Surely you remember it: Hugh Grant is an adorably floppy-haired British bookshop owner who just happens to find himself the love object of a visiting American screen goddess, played by Julia Roberts. (There’s also Rhys Ifans, stealing scenes as Grant’s mangy and horny flat-mate. But I digress.) At one key emotional moment, Roberts as movie-star Anna Scott tellingly quotes a famous line attributed to a genuine Hollywood love goddess, Rita Hayworth. Ms. Hayworth, who had five husbands as well as multiple lovers, is said to have noted, oh so wistfully, "Men go to bed with Gilda, but wake up with me."

Gilda, of course, was one of Hayworth’s most famous roles, She played this enigmatic femme fatale in 1946, wooing audiences, as well as co-star Glenn Ford, by tossing her auburn curls and cooing, “Put the Blame on Mame” in a famous nightclub scene. One of those forever smitten by Hayworth ‘way back then was an L.A. boy, Budd Burton Moss, who grew up to become the older Hayworth’s late-career agent and loyal friend. Budd has turned his memories of Rita (and such Hollywood names as Jack Valenti, Jacqueline Bisset, and good buddy Sidney Poitier) into a memoir he calls Hollywood: Sometimes the Reality is Better than the Dream. A 2015 follow-up to his And All I Got Was 10%, it chronicles Budd’s many movie-related adventures.

Though Budd seems to have known almost every Hollywood celeb, the heart of his second book is his international travels with Rita, who hoped for a career comeback but was stymied by the erratic behavior (much covered by the international press corps) that turned out to be a sign of encroaching Alzheimer’s disease. It was this cruel affliction that ultimately claimed her life in 1987 at the all-too-early age of 68.

So that future generations will remember Rita Hayworth in her prime, Bremedia Produktion GmbH is currently in process of filming a documentary, currently titled Rita / Gilda: Glamour & Tragedy of a Hollywood Legend. Through film clips and interviews with such stars as Robert Wagner, Edward James Olmos, Diane Baker, Millie Perkins, France Nuyen, and Constance Towers, the filmmakers hope to remind the public of Hayworth’s contribution to world cinema.. Coordinating the Hollywood side of this international production will be none other than Budd Moss, who has vigorously put all his resources behind the project. For him, part of the challenge is to show how capably Hayworth managed to define herself as a woman and an actress, in an era when the management of the Hollywood Dream Factory was an all-male club. By the same token, he’s convinced that a focus on the realities of Alzheimer’s is vital. Hayworth was the first major public personality to fall prey to the disease, so her diagnosis sent shockwaves around the world. Today Princess Yasmin, Rita’s daughter by her third husband, Prince Aly Khan, works tirelessly on behalf of Alzheimer’s victims. The princess, who holds an annual Rita Hayworth Gala to raise funds for Alzheimer’s research, has become an enthusiastic supporter of the Rita/Gilda documentary.

Today’s younger moviegoers have doubtless barely heard of Rita Hayworth. It’s a sure bet that they haven’t seen her peel off a long black glove in Gilda, haven’t seen her trip the light fantastic with Fred Astaire, who once admitted she was his very best dance partner. Here’s hoping that Gilda/Rita helps remind the world of what it has lost.

Published on December 03, 2019 12:23

November 28, 2019

Black is Beautiful in the Smithsonian's Newest Museum

Thanksgiving is, of course, a time for gratitude. I just returned from our nation’s capital full to the brim with a sense of well-being. No, I can’t say I’m grateful for the quagmire aspects of contemporary politics. The recent impeachment hearings have certainly not lacked for entertainment value, but I take no pleasure in contemplating the blows afflicting our venerable system of checks and balances. So while I was in Washington D.C., I tried to avoid thinking too hard about what was going on in the White House, and on Capitol Hill.

But if you strip Washington of its political dynamics, there’s a great deal to enjoy. One of the city’s treasures is the multi-branched Smithsonian Institution. The Smithsonian, founded by a philanthropic Englishman in 1846, now encompasses some nineteen museums, not to mention the National Zoo. I’m particularly grateful that admission to all these locales is completely free, so you can dip into the various collections at your leisure, without worrying about shelling out a lot of hard-earned cash.. The Smithsonian’s museums, most of them housed in imposing buildings rimming the National Mall, cover such diverse areas as American history, natural history, Native American culture, and the history of air and space exploration. But it took until 2016 for the Smithsonian to open its newest branch, the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture is still so new that visitors must line up to enter (and on weekends still need to reserve their spots in advance). Housed in a strikingly cantilevered building whose outer skin manages to look like basketry, it occupies a prime spot not far from the Washington Monument. Naturally, the heart of the museum is its sobering history section, which lays out how black slaves oh-so-gradually evolved into full-fledged citizens. It’s an evolution that has often stalled, needless to say. I’ll only mention here the painful and eerie corner devoted to the memory of 14-year-old Emmett Till, who in 1955 was brutally murdered for apparently whistling at a white woman while visiting relatives in Mississippi.. Here’s one place where video footage has the power to smack us between the eyes, as we realize what cruelty was visited upon the fresh-faced young boy from Chicago.

Upstairs, for a complete change of pace, there are exuberant galleries celebrating the highlights of African-American achievement in sports, in music, in popular culture, and in the entertainment field. In the area of television, I enjoyed the tribute to the late Diahann Carroll, who by way of the gentle sitcom called Julia showed that a black woman could be a full-fledged part of middle-class family life. (Carroll later, in Dynasty, got to be an All-American vixen.) The museum addresses the more problematic history of African-Americans in movies by acknowledging the bad old days when “colored folk” were automatically considered sex-crazed villains (Birth of a Nation) or loyal retainers (Gone With the Wind.) But the vast majority of film clips on display feature black performers in power roles, up to and including Pam Grier as a tough vigilante in Coffy. Sidney Poitier, revered in mid-century films for making nice to white men (and women) in such box-office hits as The Defiant Ones, Lilies of the Field, A Patch of Blue, and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, is instead shown in a powerhouse scene from A Raisin in the Sun. The one love scene on display features two gorgeous black performers, Harry Belafonte and Dorothy Dandridge in Carmen Jones. And even Hattie McDaniel, “Mammy” herself, is seen showing a white soldier who’s boss. .

Happy Thanksgiving to all!

Published on November 28, 2019 12:57

November 26, 2019

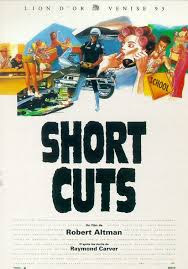

A Shortcut into the World of Raymond Carver

Robert Altman has never been accused of artistic cowardice. The director (and often the writer) of such films as MASH, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, Nashville, and Gosford Park, liked nothing more than gathering stars of all persuasions into stories that require ensemble acting. Perhaps his most remarkable achievement along these lines was taking the body of cryptic short stories by American master Raymond Carver and organizing nine of them (along with a narrative poem) into a complex, multi-faceted narrative. The film, called Short Cuts, made its debut in 1993, five years after Carver’s death.

I didn’t know much about Raymond Carver until I tackled the major biography published in 2009 by a colleague I met through BIO, the Biographers International Organization. The very talented Carol Sklenicka (whose upcoming biography of writer Alice Adams comes out December 5) spent more than a decade talking to everyone in Carver’s orbit. In her Raymond Carver: A Writer’s Life , I learned a great deal about a guy from a blue-collar family in the Pacific Northwest who put his writing ahead of just about everything else. His characters are hard-scrabble folk, some of whom (like Carver himself) are all too fond of booze. They can be crass and crude, especially to those who love them, but they’re also subject to moments of surprising tenderness. The stories are realistic in the telling: there’s little in the way of heroics, and no literary fluff involved. Fans of the Oscar-winning Birdman may remember that Michael Keaton’s character, eager to shrug off his superhero persona, is desperate to stage a kitchen-sink Broadway production of Carver’s “What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.”

In the course of a thirty-year writing career, Carver made several stabs at screenwriting.. Over time, some of his own stories were turned into short films by others, but Robert Altman was far more ambitious in his approach. Moving the Carver stories to gritty Southern California neighborhoods, he carefully interwove them, so that the driver of the car that hits the little boy in “A Small Good Thing” is the waitress with the jealous spouse in “They’re Not Your Husband.” And the men who ogle that waitress in that story’s diner are headed for the fishing trip that’s central to “So Much Water So Close to Home.”

Leave it to Altman to come up with an amazingly potent cast, one that includes Lily Tomlin as that waitress and Tom Waits as her hubby, Others in on the action include Julianne Moore, Buck Henry, Matthew Modine, and Frances McDormand,. To put a SoCal spin on the stories, Peter Gallagher plays a medfly-spraying helicopter pilot named Stormy Weathers, while Robert Downey Jr. is a make-up artist with a kinky streak. The meshing of so many stories mostly works, but I have my gripes. One story wholly invented by Altman, involving a classical cellist with severe mental issues, seems too baroque and show-offy for Carver’s world. And though the meshing of plot lines leads to some hilarious moments, it also works against the richest of the Carver stories. The climax of “So Much Water,” involving a woman’s ambiguous grief over the death of someone she doesn’t know, doesn’t seem nearly as strong on film as it does on the page. And though the gut-wrenching loss within “A Small Good Thing” (in which Andie MacDowell and Bruce Davison keep a bedside vigil for their young son) may be enhanced by the sudden appearance of Jack Lemmon as Davison’s oblivious father, the story’s heart-tugging coda lacks force. Still, if Short Cuts leads viewers to Carver, who can complain?

Published on November 26, 2019 12:56

November 22, 2019

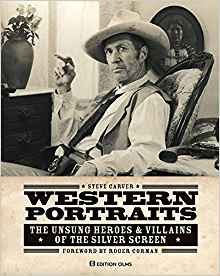

Capturing Old Hollywood by Way of “Western Portraits”

Cowboy hats. Bolo ties. Natty vests and fringed jackets. Silver belt buckles studded with turquoise. This was the garb of choice last Tuesday at the Autry Museum of the American West. In my everyday street clothes, I certainly felt underdressed.

We were all there to honor Steve Carver, whom I’ve known since he directed Big Bad Mama for Roger Corman’s New World Pictures back in 1974. After racking up more than a dozen feature film directing credits, Steve returned to his first love: still photography. Just in time for holiday gift-giving, he has published Western Portraits: The Unsung Heroes and Villains of the Silver Screen. It’s a carefully curated book of art photography, featuring well-known character actors from Steve’s Hollywood days decked out in western regalia. The cover is emblazoned with an unforgettable portrait of Steve’s longtime friend, the late David Carradine, complete with cigar and Stetson. Carradine solemnly stares out at the viewer with a tough-guy look that won’t be denied.

The power of Steve’s portraits grew out of his fascination with nineteenth-century photographic techniques. The pioneering work of Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) in chronicling the Old West has influenced Steve’s own methodology. He uses slow speed film that requires his subjects to hold a pose for a long few seconds. And—actors all—they are given the opportunity (through a series of conversations with Steve) to chose their characters and settings, within a wide range of Western environments. Buddy Hackett, for instance, is depicted with part of his collection of antique firearms. As Steve puts it, for his subjects this was “not just a snapshot. This was an experience.” He also insists that the stillness required for his very special photographs results in the subjects’ sharing of themselves. These are, he says, “pictures of their souls.”

To round out the volume, there’s a detailed filmography of all the western movies in which these actors have appeared. And Steve’s close friend, the novelist and screenwriter C. Courtney Joyner, has contributed essays based on his interviews with those of Steve’s subjects who are still with us. A sad number of those who have posed for Steve’s camera over the years are gone now, including R.G. Armstrong, Horst Buchholz (best known for The Magnificent Seven), Karl Malden, and—within the past year—both Morgan Woodward and Robert Forster.

What I hadn’t quite realized when Steve first mentioned this project to me, many years back, was how many enthusiasts there are for anything connected with the Old West. I saw that enthusiasm for myself at the Autry, where Western Portraits was the featured attraction of Rob Word’s long-running interview show, A Word on Westerns. Decked out in a jacket designed by the famous Nudie, Word was on hand to interview both Steve and Courtney with cameras rolling. And many of the book’s still-living subjects (actors like Bo Svenson, L.Q. Jones, Jesse Vint, and Fred “The Hammer” Williamson) came forward to pose for a group photo, as the audience in the packed auditorium cheered them on.

Clearly, it’s a tight-knit community. Attendees, hugging copies of Steve’s book, sought autographs from their favorites. And even some TV western stars who weren’t included in the book showed up for this very special occasion. Johnny Crawford of The Rifleman fame was there, now (alas) in the throes of Alzheimer’s disease. Tommy Nolan, who once starred as Jody O’Connell on a series called Buckskin., reminisced about his long-ago showbiz past. Nolan, now a biographer-friend of mine, had left his Stetson at home. But not his passion for the Old West, as seen through Hollywood eyes.

Dedicated to the memory of Indiana

Published on November 22, 2019 00:09

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers