Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 63

October 16, 2019

Reflections on My Breakfast with Robert Forster

I first met the late Robert Forster under a marquee on Hollywood Blvd.. We’d both just emerged from the screening of a 2014 documentary called That Man, Dick Miller, a tribute to the diminutive actor who’d spent six decades playing oddball movie roles, mostly for Roger Corman and his famous alumni. Forster was featured in the documentary, talking about a longtime friendship with Miller. Afterwards, I saw him standing alone as well-wishers swirled around Dick and his producer-wife Lainie, and I couldn’t resist introducing myself.

I think Robert liked the fact that I praised not his Oscar-nominated performance as bail bondman Max Cherry in Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown but rather his small, crucial role as a grieving father in Alexander Payne’s The Descendants (2011). Actors usually appreciate being noticed for their more subtle work. And I think he was pleased that I knew his largely silent but hugely symbolic role as a young soldier who’s the object of Marlon Brando’s unrequited lust in John Huston’s Reflections in a Golden Eye. This film, released back in 1967, was his very first movie: it required him to look soulful while riding through the countryside, stark naked, on a big white horse. For those who’ve seen this fascinating, exasperating film, Forster (then a chiseled raven-haired Adonis) is not easy to forget. The part led to him playing a cunning Apache hunted down by Gregory Peck in The Stalking Moon and then Haskell Wexler’s cameraman alter-ego on the streets of Mayor Daley’s Chicago in the timely Medium Cool.

I must have made a good impression, because when I told Robert I’d be happy to feature him in a Beverly in Movieland blogpost he invited me to breakfast at his favorite West Hollywood café. With my usual talent for underestimating L.A. traffic, I arrived some fifteen minutes late, while he was happily consuming his daily bacon and eggs special. But he warmly forgave me, and seemed glad to describe for my tape recorder a career that was not short on ups and downs. He’d fallen into acting in college, as a way to get to know an attractive classmate he later ended up marrying (and, years later, divorcing). While riding high, he’d shared scenes with some of Hollywood’s biggest movie and TV stars. That’s when he found it easy to dream about someday owning a home on the beach in Malibu. Then came a low period, one in which Roger Corman flicks seemed his best hope. (In 1994 he played a featured role in a film I actually worked on in my Corman days, the trashy but enjoyable Body Chemistry 3: Point of Seduction.) Hardly a snob, Robert had fun with this sort of shlock. But three years later, Quentin Tarantino rescued him from the B-movie world with Jackie Brown, and Hollywood discovered all over again how appealing he could be on screen, even now that his once-black hair was fast receding.

When I breakfasted with Robert in late 2014, he was full of gratitude that Jackie Brown had resuscitated his career, leading to important roles in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive and on the final episode of TV’s Breaking Bad. The day he died of brain cancer, Netflix broadcast El Camino: A Breaking Bad Movie, in which he reprised his TV role of Ed Galbraith, enigmatic vacuum repairman. I know such meaty parts brought him a lot of joy. Not that he was still fantasizing a Malibu beach-house. As he told me, he was quite content to know that acting had bought him a West Hollywood condominium.

Published on October 16, 2019 10:14

October 11, 2019

The Lovable “Loves of a Blonde”

Long before the late Milos Forman was a two-time Oscar winner (for directing 1975’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and 1984’s Amadeus), he was a valued member of what’s been called the Czech New Wave. Starting as a documentary filmmaker, he moved on to low-key black & white dramas that realistically depict the daily lives of his countrymen and women. His second feature, known in English as Loves of a Blonde, earned him an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Language Film in 1967. It also earned him a trip to Hollywood, where he was warned by a friendly publicist not to expect future success in America. (True, he lost out in the 1967 Oscar race to Claude Lelouch and his uber-schmaltzy A Man and a Woman, but Forman—from the 1970s onward—quickly became known as an essential American director.)

It’s taken me all this time to see Loves of a Blonde, but it was worth the wait. Not that this is a film with a huge excitement quotient. No gunfights; no special effects; no wild and crazy extravaganzas. (Forman’s slightly later The Fireman’s Ball is an outrageously satiric comedy about Czech bureaucratic ineptitude, a film that was “banned forever” once the Soviets marched into Czechoslovakia in 1968.) Instead, Loves of a Blonde is a small wistful story, about a young Czech woman looking for romance.. Andula, like most of her friends, works in a shoe factory in a small town with little to offer. The women are housed in dormitories, and since the local female/male ratio is 16 to 1, they have few chances to enjoy the company of the opposite sex. Their boss persuades the local government to billet a military unit in the area, in hopes of improving everyone’s social life. It mostly doesn’t work: there’s a long, funny sequence, set during a mixer at a drab social hall, in which the mostly middle-aged army reservists (some of them married) try gracelessly to entice the young women into the nearby woods for some serious canoodling.

Andula, though, hits it off with the event’s young piano player, who (after a battle with a stuck window shade) talks her into bed. He also off-handedly gives her his address in Prague. In no time flat, she’s arriving with a little suitcase, ready to pursue the relationship further. Only problem: he lives with his parents, and they’re not at all happy to put her up for the night.

Years after this film was made, Forman was videotaped talking about how he made it. It all began with a real-life incident: while walking one night down a Prague street, he encountered a young woman with a suitcase. She told him she had come to the big city to see her boyfriend, but the address he’d given her was a fake. This encounter sparked the film, which Forman cast mostly with first-time actors. The leading role was memorably played by Hana Brejchová, the younger sister of Forman’s then-wife, for whom this was a first film. Though her piano-playing lover was an experienced young actor, his exasperated parents were total amateurs. How did Forman get what he wanted from non-professionals? He explains that he never gave them a script, but instead simply talked through the emotions he sought to elicit. Without needing to replicate a script’s exact wording, they effectively delivered the mood he wanted them to convey. And the big mixer scene benefitted from his use of two cameras. One was fixed on the main actors; the other swept the hall, capturing the emotions of everyone there assembled. It worked: true slice-of-life.

Published on October 11, 2019 11:09

October 8, 2019

A Play is Not a Movie: Ethan Coen Discovers the Stage

No one does macabre and quirky like the brothers Coen. I’ve been a fan since their very first film, Blood Simple, back in 1984. I love the comedy of Raising Arizona, the poignance of Inside Llewyn Davis, the grim high seriousness of No Country for Old Men, the sheer goofiness of The Big Lebowski. I particularly cherish Fargo (1996) as perhaps the most superlative blending of the Coens’ various moods and talents.

Given that both Coens have so spectacularly succeeded (over the last 35 years) as writers, directors, and editors of motion pictures, it’s not surprising to see them branching out in other artistic directions. Recently Ethan Coen has been trying his hand at playwriting, exploring a new medium that’s perhaps not as flexible as film. The Mark Taper Forum, a semi-adventurous theatre space at the Los Angeles Music Center, has recently premiered a suite of Coen’s short plays, under the umbrella title, “A Play is a Poem.” The city’s number-one theatre critic, Charles McNulty of the Los Angeles Times, came down extra-hard on this effort, essentially advising Coen to stick to movies and suggesting that the theatre was wasting time and money by giving one of its coveted slots to a production because it was fronted by a big Hollywood name I myself was somewhat less critical, and yet I can’t deny that the five playlets are slight indeed, mostly skits of various degrees of interest united by no common theme or thread.

The Coen film most recently in theatres is 2018’s The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, a collection of six vignettes, some of them based on existing tales of the Old West by such authors as Jack London. Maybe this is part of a new trend for the Coens: producing short, punchy dramatic pieces rather than making the effort to sustain a longer, more complex narrative. But though the episodes in Buster Scruggs reflect different moods, ranging from the comic to the eerie, they are unified by their western setting and by an ongoing fascination with the abrupt end of life. A Play is a Poem is a far different matter. Each of these plays takes place in a different environment and requires a different (and often cartoonish) accent. “The Redeemers” is a dark, gruesome tale featuring some hillbilly yokels and leading the audience to a collective groan as the lights go out. “A Tough Case” is a kind of film noir parody featuring a fast-talking detective à la Sam Spade. In “At the Gazebo,” the accents are 19th century Southern, and the dialogue is so repetitious that (I admit it!) I nodded off midway through. The Southern belle and her would-be beau of this playlet are replaced in “The Urbanes” by New Yawkers struggling with their kitchen-sink lives (I did love the rattle of the El repeatedly going by their grimy window.)

The last of the plays, “Inside Talk,” was my favorite, because it trades upon Coen’s inside knowledge of the ways of Hollywood. Its central figure is a movie exec contending with two would-be producers trying to sell him on their various projects. One proposes “Das Boot on a Boat,” overlooking the fact that the original took place on a World War II submarine. The second hypes “Sobibor, Mon Amour,” a romcom with flashbacks to the Holocaust. Priceless to me was the exec’s disdain for the screenwriter’s perspective on all this: “What does the writer know? If he knew anything, he wouldn’t be a writer.” This casual dismissal of the writer as unimportant is classic Hollywood thinking. As, of course, the Coens know all too well.

Published on October 08, 2019 12:34

October 4, 2019

No Joke(r): The Rise of the Villain

As Joker leers its way into theatres, I’ve been thinking about my own experience with movie villains. As a small child, living in a world whose boundaries were established by Disney animated features, I knew exactly who was good and who was bad. Princesses, orphans, and girls with golden locks were good. So were handsome princes who rode white horses. Many of the bad characters were female too: wicked stepmothers, jealous queens, and such, though male baddies were also lurking around.

As I grew older and learned to appreciate great literature, I quickly discovered that good and bad could be relative terms. A fictional presence who was entirely good would be insufferable. And, as characters like Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov taught us, someone who commits a heinous crime can be fascinating. Still, in the movies I favored, I liked being able to root for a protagonist with whom I could identify. Such was the case with Dustin Hoffman’s star-making role as Benjamin Braddock in The Graduate. Hoffman’s recent college graduate was not exactly a role model. He behaved rudely toward his parents and their friends, was ungrateful for the many gifts he’d been given, jumped into bed with his father’s business partner’s wife, and then made a pest of himself around her beautiful young daughter. Still, there was always the sense that he meant well, and my own identification with the challenges faced by the Baby Boom generation made me appreciate Ben’s role as a young man of the Sixties facing a world that failed to understand him. (It was all too natural to place Mrs. Robinson – the desperate housewife who had problems of her own – in the villain’s role.)

When I started making so-called exploitation films (aka B movies) for Roger Corman in 1973, I really learned to appreciate terrific villains. When he was still directing his own movies, Roger had rather brilliantly peopled his Edgar Allan Poe adaptations with actors like Vincent Price who could convey a kind of haunted villainy that was both appalling and appealing. In the late Sixties, Corman also made an attractive anti-hero out of Peter Fonda in The Wild Angels and The Trip. While I was Roger’s story editor at Concorde-New Horizons Pictures in the 1980s, some of the hottest movies around were dominated by villains so hideous that they outshone the puny heroes who (temporarily) brought them down. I’m thinking of series like Friday the 13th and, A Nightmare on Elm Street. Since it was suddenly all about bad guys, we at Concorde needed to concoct our own, like the notorious (and sexy) Driller Killer of our Slumber Party Massacre films. (Yes, he had his fans.)

Even Disney animation has (sort of) gotten into the act, scoring big with a film in which the princess is NOT saved by a guy on a horse from the clutches of a magically powerful queen. In Frozen, the princely suitor is a useless jerk. And the young queen Elsa, whose powers make her dangerous, unites with her plain-Jane younger sister to keep her dark magic under control. So what could be villainy ultimately morphs into a force of good. As in (sort of) the stage hit, Wicked.

Comic books (and comic book movies) are the last refuge of the classic good/bad dichotomy. Which makes it interesting indeed that the new Joker, with Joaquin Phoenix in the central role, devotes itself to the origin story not of a hero but a villain. The focus is on an origin story for the man, Arthur Fleck, who evolves into Batman’s eternal nemesis. You can bet there will be blood.

Published on October 04, 2019 09:49

October 1, 2019

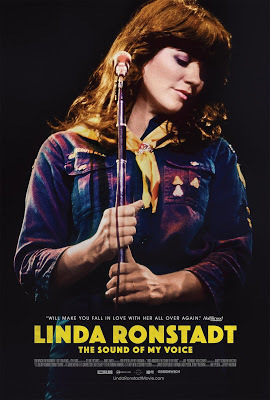

Of Note: Linda Ronstadt and the Sound of Music

What’s sadder than a singer who can no longer sing? It happened to Julie Andrews as a result of nodules on her vocal chords: she lost the pure soprano that had made her the toast of Broadway (My Fair Lady) and Hollywood (The Sound of Music.) But (now 83) Andrews continues to thrive as an actor, children’s book author, and all-around sunny media personality. Now, to the shock of millions of fans worldwide, something similar has happened to one of the pop world’s greatest voices. In 2013, a few years shy of age 70, Linda Ronstadt announced she was retiring from music-making. The reason? She was dealing with fallout from Parkinson’s Disease, which has destroyed her once-powerful vocal instrument.

I remember Linda Ronstadt fondly. As a college student, I recall attending a packed event at UCLA’s Pauley Pavilion, featuring one of the really big pop groups of the era (Peter, Paul, and Mary, perhaps). The opening act was a little trio called the Stone Poneys, led by a pretty young woman in a short skirt and bare feet. Yes, Linda Ronstadt. Her voice was strong, and seemed capable of bouncing from power ballads to country tunes to gospel to good old rock ‘n’ roll. It wasn’t long before she became a solo act—and the highest paid woman on the rock scene.

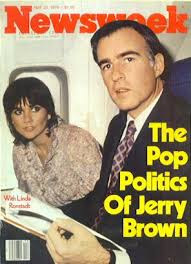

In the 1970s she was a media celebrity, whether or not she wanted to be. We Californians were both intrigued and bemused when she started dating Jerry Brown, our state’s bachelor governor, circa 1979. In that era, he was an off-again on-again presidential candidate, and their trip together to Africa got plenty of press attention. You could spot the duo on the covers of Newsweek, US Weekly, and People. She also seemed to have a thing for other big names, including (in the 1980s) Jim Carrey and George Lucas.

Much of this shows up in a highly sympathetic documentary. Linda Ronstadt: The Sound of My Voice, which debuted at the Tribeca Film Festival in April 2019, and is currently in cinemas nationwide. It’s filled with plenty of concert footage, showing Ronstadt at various stages of her career. (We see her looking sexy in an authentic Cub Scout shirt and neckerchief, though the doc doesn’t mention how upset the Boys Scouts were when she dared to desecrate their official garb.) And there are loving tributes from such musical legends as Jackson Browne, Don Henley, and Bonnie Raitt. Particularly special is her loving interaction with sister artists Emmylou Harris and Dolly Parton, with whom she’s shown harmonizing on a rousing number or two.

What pleased me greatly was the fact that this film remembers the ways in which Ronstadt spread her wings by trying out new musical styles. When she took on, very creditably, the coloratura role of Mabel in a Broadway revival of The Pirates of Penzance, interest in the 19th century wit of Gilbert and Sullivan rose tremendously. I loved what she did in the 1980s, under Nelson Riddle’s baton, with such classics as Billy Strayhorn’s “Sophisticated Lady” and “Lush Life” from the Great American Songbook. And fans of Mexican music were thrilled at her tender Spanish-language Canciones de Mi Padre.

Ronstadt’s eclectic approach is explained by the fact that “I don't record [any type of music] that I didn't hear in my family's living room by the time I was 10.” Her parents gave her a wide-ranging love for all things musical. At the end of the documentary, she’s back in Tucson, somehow (despite her damaged voice) still happily making music with her nephews.

Published on October 01, 2019 18:12

September 27, 2019

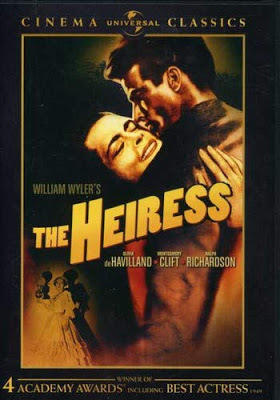

What Have We Inherited from “The Heiress”?

Does The Heiress, an oldie from 1949 based on a Henry James novel called Washington Square, have anything to say to us today? In this #MeToo era, we’re all aware of women who’ve been pressured by men into unwanted sexual activity. Being a woman now—at a time when sexual compliance is often expected as a quid pro quo for favors received--is hardly easy. Still, it’s got to be an improvement on the nineteenth century, when a woman’s entire life was based on the obligation to marry and produce heirs.

Catherine Sloper, who lives with her doctor-father in an elegant Greenwich Village mansion, has what may seem an easy life. Having no need to earn her living, she devotes her time to embroidery, pretty dresses, and making homelife comfortable for her widowed papa. He pays her back by comparing her—in strongly negative terms—to her dead mother, whose good looks and charm the shy Catherine can’t hope to approximate. It’s clear to her that he considers her an abject failure, because no eligible bachelor seems willing to look at her twice.

Everything changes when, at a posh neighborhood soiree, she is asked to dance by the handsome Morris Townsend, just back from a swing through Europe. Almost immediately he is courting her, and she is falling head over heels in love. Their quick engagement is applauded by her giddy aunt, who thrives on the romance of it, but Dr. Sloper is sure from the start that the attractive but impoverished Morris is a fortune-hunter. To the good doctor, it’s clear that Morris Townsend is attracted less by Catherine’s quiet charm than by her future financial expectations.

So sure is Catherine that her beloved wants her for herself alone that she chooses to face disinheritance by organizing a late-night elopement. She’s thrilled by the prospect of leaving the family home forever, and going off into a future where she and Morris will live on love. Alas, we’re not surprised when her betrothed leaves her in the lurch, and all her romantic dreams turn to dust. The true suspense in the story comes when—several years later—Morris returns from far-off California to resume his courtship. By this point, Dr. Sloper is dead, and Catherine is the mistress of both her house and her desires. From this position of power, how will she react to Morris’s pretty speeches about why he abandoned her (for her own good, of course) all those years ago?

Catherine Sloper was played by Olivia de Havilland, now still alive and feisty at 103. It was she who brought a successful Broadway play to the attention of William Wyler, insisting on playing the role that ultimately brought her an Oscar. Ironically, de Havilland is perhaps best known as the sweet, docile Melanie in 1939’s Gone With the Wind. Her petite prettiness was not ideally suited to the role of Catherine, despite the valiant attempts of the production staff. Yet in the latter sections of the film, the steel in her spine seems quite genuine. Britain’s Ralph Richardson was Oscar-nominated for playing her father, subtly conveying the sense of a man who doesn’t realize how hatefully he’s treating his only child. I also admired veteran charmer Miriam Hopkins as the flighty aunt. But Montgomery Clift, starting to get a reputation as sensitive leading man, somehow seems too modern for this very period piece. Kudos to William Wyler for his elegant direction (which makes vivid use of the house’s massive staircase), and to Aaron Copland, who won an Oscar for bringing his symphonic gifts to the film’s score.

Published on September 27, 2019 09:30

September 24, 2019

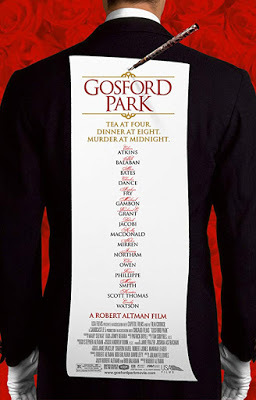

Gosford Park: Down the Road From Downton Abbey

While the residents of Downton Abbey await the arrival of the British royal family (and the producers wait for their box office returns to come rolling in), I’ve gone back to a Julian Fellowes-penned film that inspired the televised saga of the aristocratic Crawleys and their upstairs/downstairs world. Gosford Park, a feature film from 2001, boasts a starry British cast. It’s led by Helen Mirren, Clive Owen, Emily Watson, and Kelly Macdonald as below-the-stairs folk, as well as Michael Gambon and Kristin Scott Thomas as their social betters. Downton’s Maggie Smith is also present, stealing scenes as is her wont, as a stuffy but impoverished aristo who huffs that “there’s nothing more exhausting than breaking in a new lady’s maid.”

It’s 1932, in that oblivious period between two World Wars. Everyone is gathered at Gosford Park because the McCordles are staging a shooting party, with the menfolk traipsing out to the fields to blast away at defenseless game birds. But many more games are afoot, involving sexual infidelities, desperate attempts to raise money, and long-simmering class resentment. Occupying a special niche are three interlopers from Hollywood. One is Ivor Novello, an actual British entertainer and matinee idol of the period, whose skill at tickling the ivories causes many hearts to flutter, both in the drawing room and in the servants’ quarters. He’s good at hobnobbing with the wealthy, but hardly considers himself part of their world. (When someone asks how he puts up with the snobbery of the ruling classes, he simply shrugs, “I make a living impersonating them.”)

The chap doing the asking is another Hollywood type, a hearty American named Morris Weissman, whom Novello has brought along because he’s researching his latest film. Weissman, played by the diminutive Bob Balaban, is almost certainly Jewish, and it’s clear that his ethnicity as well as his nationality and his occupation taint him unforgivably in the eyes of his snooty hosts. (To make matters worse, both hosts and staff are appalled that he won’t eat meat.) Novello and Weissman are accompanied by an apparently Scottish valet (Ryan Phillipe) who seems to be up to no good.

In fact, someone in the household is definitely up to no good. Weissman explains that though his new film will be titled Charlie Chan in London, it’s mostly set in a stately country estate, where a shooting party ends in a murder, and everyone present becomes a suspect. Ironically, this is exactly what transpires, though the bumbling local constabulary is far less effective than Charlie Chan would be in tracking down the killer.

While playing a key role in the film, Balaban also served as one of its producers. Gosford Park came about when he and Robert Altman decided to work together. Director Altman, who’s more usually associated with All-American stories like Nashville and McCabe and Mrs. Miller, delighted in working with a British ensemble blessed with strong theatrical chops. Always experimental, he had two cameras going at once, and actors—never sure of when they’d appear on camera—were encouraged to improvise when they participated in the film’s many crowd scenes. The result is both fascinating and frustrating: there are times when so much is going on that it’s hard to follow the logic of basic plot lines. (And, dash it all, some of those well-coiffed lords and ladies do quickly start to look alike.) Still, this is an elegant treatise on class distinction. Who knew that in the very best houses the servants are expected to call each other by the names of their masters?

Published on September 24, 2019 16:24

September 19, 2019

Toni Morrison: Not so Beloved by Hollywood

Since the death of Toni Morrison on August 5 of this year, I’ve been thinking about the great American novelists, and why the translation of their books into film is always so disappointing. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby has been filmed five times, but I don’t believe any of these versions truly captures what makes the novel so magical. Hemingway adaptations have their moments, but none of them is totally representative of what Hemingway brought to American fiction. John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath was indeed made by John Ford into a beloved film, with unforgettable performances by Henry Fonda as Tom Joad and Jane Darwell as his indomitable mother. Still, the film lacks those great lyric passages that lift Steinbeck’s novel into the realm of the universal. As for Faulkner, I had the misfortune to see in a theatre Hollywood’s attempt at filming The Sound and the Fury. The 1959 film starring Joanne Woodward and (oddly enough) Yul Brynner ditches any attempt at reproducing Faulkner’s experiments with point of view, merely concentrating on the plight of some sad Southern aristocrats. (I actually watched this fiasco as a kid, because it was a double-bill companion to Disney’s The Shaggy Dog. Go figure!)

Most of the authors I’ve mentioned above were winners of the Nobel Prize for literature. (Fitzgerald is the one exception.) Morrison was a Nobel-winner too, and to me there was no American novelist more deserving. Morrison’s range was wide: though she wrote exclusively about African-Americans, she covered many eras and perspectives, and also explored many styles. If one sign of mastery in a novelist is the ability to create and flesh out an entire universe, she achieved true greatness in her eleven full-length works. And then there’s her way with words. Praising her astonishing third novel, Song of Solomon, the writer Reynolds Price declared that “Morrison’s gifts for observing and transforming a spacious visible world into its matching mirror-world of sound and rhythm had grown to the point of overflow; and Song of Solomon is the first display of a suddenly effortless power that can not only hold us but can promise to spread, not only in the reader’s memory but in the writer’s work to come.”

Price is right to focus on Morrison’s distinctive use of sound and rhythm, which shows up not just in her characters’ dialogue but in the ebb and flow of the narrative voice. It is this voice – the distinctive use of words by a gifted author – that is so very hard to convey on screen. Which is one good reason why filmmakers have been reluctant to touch Morrison’s novels. The one big exception is the film version of Beloved, released to modest critical acclaim and poor box office in 1998. Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Beloved, which moves back and forth through time to tell a chilling tale of slavery and its aftermath, had the advantage of a strong commitment from Oprah Winfrey, who owned the screen rights for a decade before managing to pull together a film production with herself and Danny Glover in leading roles. Oprah’s all-in performance is admirably strong, and the film directed by Jonathan Demme is evocatively cast, filmed, and scored. Yet Morrison’s complex and convoluted narrative, with its mysterious supernatural elements, is not easy for a viewer to fathom. Beloved is in many respects a ghost story. But the film is less haunting than confusing, and even someone with Oprah’s gift for generating publicity couldn’t save it. Beloved is an honorable failure as a film. But I suspect there are some page-to-screen projects better left untouched.

Published on September 19, 2019 08:47

September 17, 2019

Felicity Huffman is the New Black

So Felicity Huffman is going to prison. I confess I’m feeling sorry for her. Well, sort of. As Hollywood celebrities go, she’s always come off as a decent, down-to-earth type. She’s admitted wrongdoing in the college admission bribery scandal, and there’s a part of me that understands (even though I don’t endorse) mothers who do crazy things to smooth their children’s path. On the other hand, privilege undeserved is ugly indeed, and I hate the thought of buying your way into a prestigious college, particularly if this comes at the expense of a more worthy candidate.

So Felicity Huffman is going to prison. I confess I’m feeling sorry for her. Well, sort of. As Hollywood celebrities go, she’s always come off as a decent, down-to-earth type. She’s admitted wrongdoing in the college admission bribery scandal, and there’s a part of me that understands (even though I don’t endorse) mothers who do crazy things to smooth their children’s path. On the other hand, privilege undeserved is ugly indeed, and I hate the thought of buying your way into a prestigious college, particularly if this comes at the expense of a more worthy candidate. When I read about the Huffman sentencing, my mind immediately raced to imagine a nice-girl type who—because of a single moral slip-up—is suddenly thrust among hardened criminals (thieves and murderers at the very least) and wonders whether she’ll have the fortitude to survive. This, of course, has been a major throughline of TV’s ultra-popular Orange is the New Black. One of this show’s virtues is its mixing of types: its cast members represent all sizes, all shapes, all backgrounds, all approaches to life. Prison (like a military platoon) makes such a compelling setting for a drama: because it begins with a high-pressure environment, then stirs together characters who wouldn’t naturally interact unless they were pulled away from their native habitats and forced to spend time together, 24/7.

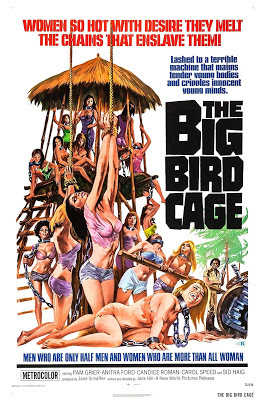

Thinking about Orange is the New Black sends me back to my B-movie roots. When I first went to work for Roger Corman at New World Pictures, back in the good old days of grind-houses and drive-ins, we made lots of moolah on the Women in Prison genre, with down-and-dirty movies (usually shot in the Philippines) that featured babes behind bars. Realism was of no particular interest to us. Nor, of course, was originality. Flicks with titles like The Big Bird Cage and The Big Doll House (and, inevitably, The Big Bust-Out) all featured unfortunate gals in skimpy prison garb, unfairly confined to jungle prisons. Such prisons, needless to say, were presided over by evil wardens and Lesbian matrons (of the Barbara Steele variety) who found torture amusing. And of course the cast was diverse: the vulnerable newbie, the tough gal (Roberta Collins made a good one), the powerful black Valkyrie. Pam Grier got her start in this latter sort of role, long before she proved her chops in Tarantino’s Jackie Brown.

The women start out hating and mistrusting one another, leading to the ever-popular cat fight in the shower room. (Needless to say, excuses for on-screen nudity are much of the reason these films exist.) But finally the gals join forces for a daring escape from their captors. When I was doing interviews for my biography, Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers, one New World alumna joked about how, in a film like The Big Bird Cage, the female lead is inevitably falling out of her clothing while running through the jungle: “I think the faster she runs, with the machete in her hand, the more quickly the clothes fall away.”

Is there anything good to be said about the Babes Behind Bars genre? Well, it launched the career of a first-time director named Jonathan Demme. When he returned from Manila in 1974 with the footage that became Caged Heat, I thought his movie looked pretty much like any other Women in Prison flick. But film critics (particularly Kevin Thomas at the Los Angeles Times) gave Jonathan credit for making a deft parody of the genre. He also scored with a nifty catch line: “White hot desires melting cold prison steel.”.

Published on September 17, 2019 12:44

September 13, 2019

Hailing “The Farewell”

It’s not often that I consult a doctor immediately after seeing a movie. But Lulu Wang’s new Sundance crowd-pleaser, The Farewell, inspired me to take aside a good friend who’s a specialist in internal medicine. I wanted to ask about issues the film has raised. Namely: what is the latest thinking on keeping the bad news from patients who’re facing a fatal diagnosis?

As I had suspected, American doctors still feel that patients are entitled to know their prognosis, no matter how grim it might be. But The Farewell, based on Wang’s own family story, takes us to China. There, in the small city of Changchun, relatives go through an elaborate charade to keep a beloved grandmother (called Nai Nai or “Grandma”) from learning that her nagging cough is a symptom of a lung cancer that will probably kill her in a matter of months. As an excuse to reunite members of a far-flung family, a cousin living in Japan is going to marry his longtime girlfriend in Changchun, with a schmaltzy Chinese celebration to follow. Through cunning and downright subterfuge, family members keep results of medical tests away from Nai Nai, and manage to maintain the joyous mood of the wedding, even when their hearts are breaking at the impending death of their beloved matriarch.

“The Farewell” started out as a story told by Wang on This American Life. In discussing her large family’s strategy for handling end-of-life issues, she focuses on herself and her role as both Chinese and American: "I always felt the divide in my relationship to my family versus my relationship to my classmates and to my colleagues and to the world that I inhabit. That's just the nature of being an immigrant and straddling two cultures." In the film, her character—named Billi—is a struggling would-be writer adrift in New York City. Emotional by nature, and deeply attached to her grandmother across the sea, she is told by her deeply-troubled parents to stay away from the wedding and its presumed aftermath. She comes anyway, and finds herself fighting to keep up the fiction that this reunion is a wholly joyous one.

Billi is played by Awkwafina, the spunky Asian-American rapper who proved her comic chops in both Ocean’s 8 and Crazy Rich Asians. Here her role is far more serious, and she handles it with grace. But the movie truly belongs to Zhao Shuzhen as the indomitable Nai Nai. Her Chinese-language performance is so spirited and so lovable that it’s easy to understand why the family dreads her loss, and why she seems able to defy her illness in the face of this unexpected family gathering.

The tail-end of this film contributes a note of hope that is most welcome, in light of what has gone before. But the truth is that I wasn’t quite as blown away as I’d hoped to be. The rave reviews for The Farewell had me convinced that its quiet charms would build toward a powerful climax. Instead, the movie amiably meanders, without giving us much in the way of tension or surprises. Still, I can agree that it’s a triumph for Wang to have escaped the demand of many potential backers that this very Chinese story include white characters, and probably a love interest too. .

By the way, medical deception may work for this Chinese family, but my doctor friend is sure that most patients want—and need—to be clued into their pending fate. When well-meaning family members keep bad news from them, they figure out the truth for themselves, leading to yet more pretending.

Published on September 13, 2019 09:09

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers