Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 65

August 9, 2019

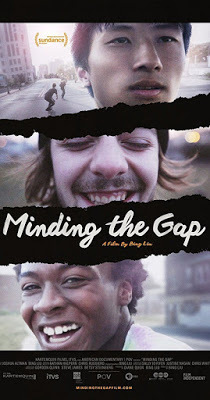

“Minding the Gap”: Middle America Rolls On

“Penny Marshall put Rockford, Illinois on the map with A League of Their Own, her 1992 movie about the Rockford Peaches women’s baseball team.” That’s the kick-off of a recent article in the Hollywood Reporter, announcing the town’s plans to honor the late director by staging a Penny Marshall Celebration in mid-September. Marshall’s daughter and grandchildren are scheduled to participate, and a highlight will be the unveiling of plans for Rockford’s International Women’s Baseball Museum.

A recent Hulu film—one that’s been nominated for both an Oscar and a primetime Emmy—shows another side of Rockford, Illinois. Minding the Gap, a documentary feature by Millennial filmmaker Bing Liu, also deals with athletics, but women who play baseball is hardly its focus. Instead, Minding the Gap plunges us into the world of skateboarding, introducing us to several young men (including the filmmaker himself) who are passionate about jumping onto a seven-inch slab of maplewood outfitted with wheels in order to sail down sidewalks, soar off ramps, and flip ecstatically skyward. Skateboarding, a sport with no formal rules, is clearly the definition of “cool.’ It seems well suited to young bodies and young minds, and when the film began I assumed it would be a paean to skateboarding as an emotional release from the mundane life of boys growing up in a drab middle-America town.

Minding the Gap is that, but also much more. What makes the film unique is the intimacy of its look at its central characters: Keire Johnson, Zack Mulligan, and Liu himself. They are all skateboard buddies from way back: Liu started filming their boarding antics when he was only fourteen years old, though it took a decade for him to decide that their stories would be the basis of his first documentary film. (He’s now reached the ripe old age of 30.) Through visual footage and on-camera interviews he brings us into their lives. Johnson is a sweet-natured,African American haunted by the death of his father soon after they had angrily parted ways. Liu, born in China, shares his own anxieties about his mother’s second marriage to a tough-minded Anglo. Mulligan, perhaps the most charismatic of the three, is a wild man on his board, but also a husband and a father who can’t seem to reconcile his competing urges to protect his toddler son Elliot and to shuck off all sense of responsibility. In the course of the film, we also meet Bing Liu’s immigrant mother, Zack Mulligan’s increasingly frustrated baby mama, and other Rockford residents who comment tellingly about the world the three young men inhabit with such obvious discomfort.

What becomes startling in the course of the film is the realization that none of these three skateboarders is a stranger to domestic violence. Keire Johnson’s childhood is remembered as a time when stringent discipline within the house was considered the best way to keep young black boys out of trouble outside it. Bing Liu , his younger brother, and their sad-eyed mother all admit they were victims of the stepfather’s raging brutality. As for Zack Mulligan, he copes with his inability to grow up by hard-core drinking and by lashing out at whomever is present. Says he to the camera at one particularly telling moment, “You can’t beat up women . . . but some bitches need to be slapped sometime.”

Minding the Gap ends with a shred of hope that these broken lives can be mended. In a poignant scene at his father’s grave, Keire Johnson muses that his dead dad’s qualities—tough discipline and love—are akin to those that skateboarding demands.

Published on August 09, 2019 08:59

August 6, 2019

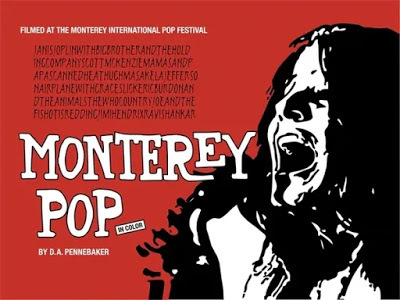

Looking Back with D.A. Pennebaker: Father of Fly-on-the-Wall Cinema

The late D.A. Pennebaker was such a force in American documentary filmmaking that this week’s New York Times obituary doesn’t even mention his seminal concert film, Monterey Pop. That 1968 documentary feature, an encapsulation of the three-day concert staged at the fairgrounds in Monterey, California in June 1967, is widely considered the first and the best of the Sixties concert films. The Monterey Pop Festival featured such major (and diverse) talents as Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, Simon and Garfunkel, Otis Redding, The Who, and sitar master Ravi Shankar. The Mamas & The Papas, whose John Phillips was one of the concert’s chief organizers, helped spread a mellow West Coast vibe that ended up kicking off San Francisco’s Summer of Love. Yes, Scott McKenzie even came onstage to sing Phillips’ “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair).” Pennebaker, using several cameramen (one of whom was fellow documentary great Albert Maysles), roamed through the crowd, intimately capturing the swirl of activity: the blissed-out concertgoers as well as such performances as Jimi Hendrix’s on-stage pyrotechnics. To watch Monterey Pop is to be immersed in the event it portrays. No wonder it was selected by the Library of Congress for inclusion in the U.S. Film Registry.

Monterey Pop was hardly Pennebaker’s only film devoted to music. He was once quoted as saying ,"The very nature of film is musical.” In the course of his long career, which included over fifty directing credits between 1953 and 2016, he lensed documentaries featuring Depeche Mode, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, John Lennon, David Bowie, Chuck Barry, and Branford Marsalis. Moving from pop to Broadway, he put on film the acerbic musical star, Elaine Stritch, in a tense moment when she broke down over her inability to record her signature song from Company, ”The Ladies Who Lunch.”

Perhaps Pennebaker’s best known film is Dont Look Now. (English majors, take note: the film’s title, borrowed from a bit of advice from Satchel Paige, is spelled without an apostrophe.) In 1965, Pennebaker (then 40) was approached by the manager of rising star Bob Dylan, and asked to make a film about the singer’s upcoming first British tour. He had barely heard of Dylan, but was game for the assignment. Using his signature fly-on-the-wall approach, Pennebaker stayed in the background, shooting everything that happened, offstage as well as on. The result was a quirky portrait of a young artist as a rebel manfully resisting every attempt to put him in a box. Here’s what I wrote about Dont Look Back at the time of Dylan’s Nobel Prize win: “In the film, a surly Dylan makes plain his refusal to be sucked into the starmaker machinery on which the recording industry is based. Whether meeting other musicians backstage or jousting with the press, he seems guarded and occasionally hostile. Determined not to be categorized, Dylan parries every label that journalists try to pin on him. No, he’s not a folksinger. No, he’s not an angry young man.”

Pennebaker records, without comment, Dylan brushing off members of his entourage (including love-interest Joan Baez) and treating a reporter from Time with open contempt. He also summons up images of this small, slight young man facing enormous, adoring concert crowds and then hustling away from them as they mob him after an Albert Hall performance. This dramatic look at the daily life of a pop star is today considered a masterpiece of cinéma verité. Without overt editorializing, it records what happened. Of course, the editing process subtly shapes what the filmgoer sees, but Pennebaker makes us feel we’re getting the truth, unfiltered.

Published on August 06, 2019 12:25

August 2, 2019

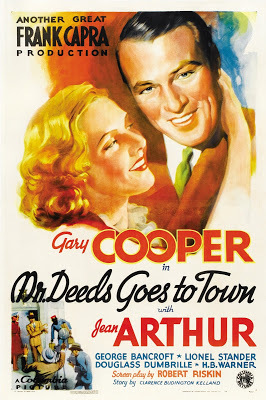

The Pixilated Mr. Deeds

Today, when the integrity of the news media is constantly being challenged, and when a man from Vermont is admired by many for his “pixilated” horse sense, it seems a fine time to look back on one of screenwriter Robert Riskin’s best collaborations with Frank Capra, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. Riskin’s daughter Victoria writes of this 1936 feature, “Of all his films, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town was my father’s favorite. It’s my favorite too, blending romance, humanity, and decency into the distinctive Riskin view of the world. Film historians call it the quintessentially American movie of the Golden Age of Hollywood.” One sign of Riskin’s own affection for this film: he gave the name of its hero to his beloved dachshund, whom he trained to fetch his newspaper each morning.

Speaking of newspapers, they don’t come off well—at least initially—in Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. In the height of the Great Depression, a millionaire has died, leaving his entire fortune to a relative living in the cozy hamlet of Mandrake Falls. Longfellow Deeds, played by Gary Cooper, is a laid-back chap who writes greeting-card poetry, plays tuba in the local band, and can never resist chasing fire engines. To claim his inheritance, he is willingly transplanted to a New York City mansion. There he enjoys fine clothes, the services of a butler, and the fun of sliding down the bannisters of his palatial home. But he is quickly skeptical of the lawyer who’s conniving to get his power of attorney, and he’s smart enough to sense that a good many people view him as a curiosity and an overgrown child. The one person he doesn’t see through is a pretty young woman named Mary (Jean Arthur in her first big role). She tells him she’s faint from pounding the pavements all day, looking for work. What he’s slow to realize is that “Mary” is actually Louise “Babe” Bennett, a hard-boiled newspaper gal who plans to scoop the competition by publishing insider stories of the eccentric new millionaire she mockingly labels “Cinderella Man.”

Of course the plot thickens, particularly after Deeds decides to give away his new fortune by dividing it into farm plots for worthy out-of-work family men. Inevitably, the film climaxes in a sanity hearing where the greedy lawyer and some conniving distant relatives scheme to have him declared incompetent. You can probably guess who comes to his rescue. And of course there’s a happy ending in which the “little man” triumphs over the powers that be. I’m glad to say that the newspaper editor who was so eager for headline stories disparaging Longfellow Deeds ultimately becomes one of his biggest supporters.

The outcome of this film, though charming, is thoroughly predictable. For me the big surprise was the talent shown by Gary Cooper for screwball comedy. Coop, who played uncredited roles in early silent movies, was usually cast as a cowboy. When, at the end of the 1920s, he finally landed leading roles, he continued to play men of action: cowpokes, soldiers, French legionnaires. He won his first Oscar as a heroic World War I soldier in Sergeant York and his second as a courageous lawman facing down a passel of bad guys in High Noon. Wonderful performances, but none of this prepared me for the charm he displays as Mr. Deeds. His Deeds is a wondrous creation: whimsical, impetuous, childlike but never childish. He may lack sophistication, but he’s brimming over in common sense. If he’s accused in the courtroom of being “pixilated,” this seems a very good thing to be.

Published on August 02, 2019 10:56

July 30, 2019

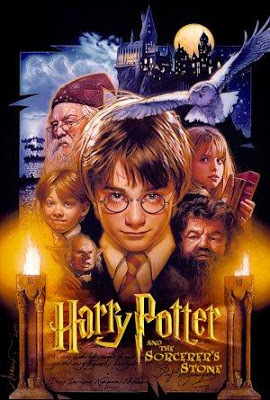

Harry Potter and the Old School Tie

Oxford, England is a town dedicated to higher education of a very exclusive sort. Everywhere you look, there are turrets, bell towers, twisting staircases, and elaborate iron gates. Also tea shops, bicycles careening down the High Street, and charming little establishments vending fountain pens. and vellum notebooks. It all looks like a medieval theme park, crossed with a swath of Victorian kitsch. Or, of course, a page out of Harry Potter.

I’ve read that J.K. Rowling, as a young woman, applied for admission to Oxford but was not accepted. If so, writing a series of internationally top-selling books has certainly been her best revenge. When the seven Harry Potter novels were filmed, the stately halls of Oxford were chosen to fill in for Hogwarts School of Wizarding and Witchcraft as well as its neighboring village, Hogsmeade. Theoretically, these key Rowling locations are supposed to be found somewhere in Scotland. But filmmakers know that you can’t do better than Oxford when it comes to quaint and musty medieval-looking structures. (It also is a mere two hours from London.)

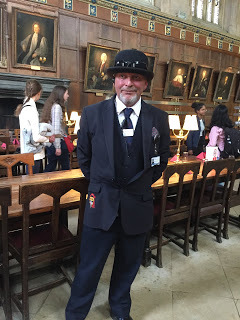

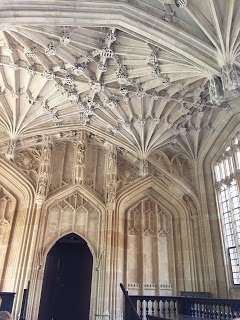

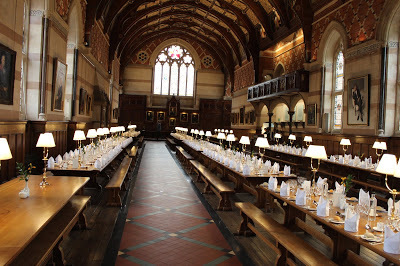

Today’s Oxford tourists—of whom there are many, from all over the globe—are so attached to the Harry Potter universe that gift shops display Potter memorabilia and there are walking tours dedicated to pointing out which college building is featured in which scene from which of the Potter films. Though I didn’t spring for any of these specialized tours, my own wanderings still put me in contact with the wonderful world of Harry and Ron and Hermione and Hagrid and Dumbledore. My guide at the venerable Bodleian Library, which dates back to at least 1602, announced with some pride that the ancient hall known as the Divinity School—noted for its spectacular fan vaulting—was used in one film to stand-in for the Hogwarts Infirmary. When I toured Oxford’s Christ Church College, founded by King Henry VIII in 1546, I learned that a certain noble staircase was the spot where Harry and friends had a key conversation with Professor McGonagall. And there was more: the Christ Church dining hall, with its long rows of banquet tables and an impressive dais for faculty members, became the model for the dining hall that plays such a key role in the first Potter film. Christ Church is served by a so-called Custodial Team, fitted out in bowler hats and formal uniforms, who explain to visitors the college’s long and illustrious place in history. They’ll grudgingly discuss the Harry Potter phenomenon, but woe to the kid who innocently asks to be shown Harry’s regular seat, or inquires about his favorite foods. When a tyke dared to ask such a question in my presence, the custodian snapped out his answer: that Harry Potter is not real. .

Try telling that to the Oxford shopkeepers who supply visitors with wizard robes, wands, and Gryffindor hoodies. .One sidewalk placard announces its shop’s allegiance as follows: Wizards Welcome. Muggles Tolerated. Of course, the rest of England is trying hard to jump on the lucrative Potter bandwagon too. A throwaway London travel guide announces (just above an entry for Westminster Abbey) family tours of Warner Bros. London studio, where you can see the sets representing Diagon Alley, Hagrid’s Hut, and the brand-new Gringott’s Wizarding Bank. And London’s King’s Cross Station now boasts its own Platform 9 ¾, to reflect the famous magical platform where Harry and his peers board the train to Hogwarts. It started out as a mere sign, but now has its own memorabilia shop, complete with a professional photographer to deck you out in appropriate Potteresque garb.

For Roz Arnold, my fellow Oxford explorer.

A Christ Church College custodian

A Christ Church College custodian The Divinity School, which morphed into an Infirmary

The Divinity School, which morphed into an Infirmary  Dining Hall, Keble College, Oxford

Dining Hall, Keble College, Oxford

Published on July 30, 2019 11:46

July 26, 2019

Mad about "Mad"

My father didn’t approve of Mad magazine. As the child of immigrants, and someone immensely grateful for the blessings he’d enjoyed as a citizen of the United States, he was drawn—especially in his later years—to entertainment that was uplifting and non-provocative. (The Music Man and The Sound of Music were special favorites.)

My father didn’t approve of Mad magazine. As the child of immigrants, and someone immensely grateful for the blessings he’d enjoyed as a citizen of the United States, he was drawn—especially in his later years—to entertainment that was uplifting and non-provocative. (The Music Man and The Sound of Music were special favorites.) My dad’s middle-of-the-road tastes are doubtless one perverse reason I gravitated toward art that made waves. By the time I was in my teens, I was discovering avant-garde poetry, esoteric novels, tough-minded theatre (think Edward Albee’s brand-new Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?), and arty foreign-language cinema. And, it went without saying, Mad. To be honest, its occasional grotesquerie didn’t always tickle my funny-bone. The tit-for-tat comic violence of “Spy Versus Spy” was a bit too real for my taste, and I wasn’t much of a Don Martin fan. (I still remember, though, one especially inspired cartoon, in which a typically crazed-looking Don Martin mad scientist holds aloft a frothing beaker and announces that by quaffing its contents he will turn himself into a creature of unspeakable horror. He drinks—but nothing happens. Disgusted, he pours the concoction down the lab sink, which instantly turns . . . into a toilet.)

What I loved was the wit and slightly skewed wisdom of Dave Berg’s “The Lighter Side” features, and, of course, Mad’s movie parodies, the work of the irreplaceable Mort Drucker. I’m happy to report, via my browsing of Wikipedia, that Drucker is still living in Brooklyn at age 90, and that his covers for Time magazine, reflecting his skill as a political caricaturist, are now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery. Reportedly, in a 1985 Tonight Show appearance, Johnny Carson asked Michael J. Fox, "When did you really know you'd made it in show business?" Fox’s prompt reply: "When Mort Drucker drew my head."

Drucker’s movie parodies were always clever, but what really made them soar was his ability to capture the physical characteristics of Hollywood’s most famous players. As the author of Seduced by Mrs. Robinson: How The Graduate Became the Touchstone of a Generation, I loved learning that director Mike Nichols didn’t realize how much his subconscious was contributing to The Graduate until he came upon “this hilarious issue of Mad magazine . . . in which the caricature of Dustin says to the caricature of Elizabeth Wilson, ‘Mom, how come I’m Jewish and you and Dad aren’t?’” And I still remember fondly how one of other great films of 1967, Bonnie and Clyde, was turned by Drucker into “Balmy and Clod.” The depictions of Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway were spot-on, and I loved how Bonnie’s real-life doggerel about their romantic life as robbers on the run was turned into something like this: “Clod and Balmy, Clod and Balmy/ Gentle as rain and strong as salami.”

But my all-time favorite Drucker parody featured his imaginative re-tread of 1961’s West Side Story. Instead of merely caricaturing Natalie Wood, Russ Tamblyn, George Chakiris, and the other Jets and Sharks, Drucker had the brilliant idea of turning the story of rival New York street gangs into “East Side Story,” with the bodies of Hollywood actors now crowned with the faces of global political leaders, those who would normally be assembling at the United Nations on Manhattan’s eastern shore. Jack Kennedy led one gang of dancing thugs; Nikita Khrushchev headed up the other. Cold War-era songs included “When you’re a Red you’re a Red all the way . . .” How long ago it now seems, and how innocent. What, me worry?

Published on July 26, 2019 10:06

July 23, 2019

Foreign Films for the Dog Days of Summer

My Life as a Dog. My Life as a Zucchini. The two films stood next to each other on the foreign film shelf of my local library. I’d heard of both but never saw either. What I discovered is that the two films, while aesthetically very different, both deal smartly and tenderly with similar subject matter. Both explore the terrors—and the wonders—of childhood, from the perspective of a young boy faced with losing his familiar world.

My Life as a Dog (originally Mitt liv som hund) is a Swedish film from 1986 by Lasse Hallström, almost his first feature after years of churning out ABBA videos. So great was its international acclaim that it was nominated for two Oscars: for best director and best adapted screenplay. (Needless to say, it’s rare indeed for a foreign-language film to be in the running in these high-prestige categories.) On the strength of this production, Hallström went Hollywood in a big way. His directorial projects have since included such winners as What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, The Cider House Rules, Chocolat, and most recently The Hundred-Foot Journey. All are marked by technical skill, deft acting, and a strongly humanistic outlook.

My Life as a Dog, adapted from a Swedish novel, focuses on a pre-teen boy, Ingemar, whose single-parent mom is dying of something like tuberculosis. Caught up in her own misery, she has no time or sympathy for his pain. So he’s sent to live with his uncle, a benevolent free spirit who lives in what seems to be a wacky community of glass-blowers. In his uncle’s village, he learns to laugh and to love. There are quirky neighbors to enjoy (the old man who gets his jollies by having young Ingemar read to him from catalogues of women’s clothing; the eccentric who decides to go swimming in the frozen lake in the middle of winter). And there are kids his own age, infatuated with soccer and boxing. It’s the era when Swedish boxer Ingemar Johansson challenged world champion Floyd Patterson. One of the toughest, most enthusiastic local boxing enthusiasts turns out to be a tomboy just Ingemar’s age. Their interaction, both pugilistic and faintly romantic, is clearly part of Ingemar’s eventual path toward adult sexuality. The film is frank regarding the curiosity among pre-teens about the opposite sex. But (despite a topless scene that raised some hackles in the U.S.) it is never less than respectful of young people’s fascination with the adult world.

My Life as a Zucchini, based on a French-language novel called Autobiographie de Courgette, was a 2017 Oscar nominee for best animated feature. It’s done in stop motion animation, featuring exaggerated characters who have enormous heads, odd hair-styles, blue-circled eyes, and huge pink ears. The quirkiness of the film’s visual style softens a story that is in many ways brutal. Young Icare, called Zucchini by his mother, is not a happy kid. His mother, abandoned by his father, is a drunk who dies early in the film, partly as a result of a household skirmish. So Zucchini is taken by a local cop to live in a group home along with other deeply troubled children. At first it seems he’ll be bullied, but he and the other kids soon form a tightly supportive unit, helped along by kindly teachers who have the children’s best interests at heart. The fly in the ointment is an evil aunt who claims one of the girls as her own, but the kids’ cleverness saves the day. So heartening to see two films in which a child’s resilience overcomes personal tragedy.

Published on July 23, 2019 11:30

July 19, 2019

Celebrating the Little Church Around the Corner: a New York Oldie But Goodie

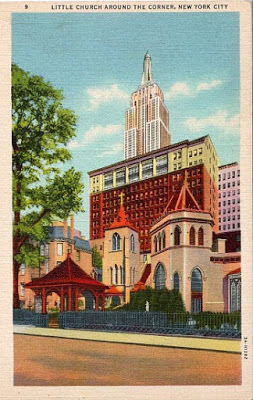

Postcard view-- The Little Church Around the CornerNew York is a forward-looking city, but also one that dotes on relics of past glories. During a recent visit, I was shown a place I’d heard about, but wasn’t sure existed. Its history is tied up with that of the American theatre, but it also gave its nickname to at least one movie, a 1923 silent drama starring Claire Windsor. And it shows up for real in Woody Allen’s Hannah and Her Sisters, when Allen’s character, attempting to convert to Catholicism, attends a concert on the premises.

Postcard view-- The Little Church Around the CornerNew York is a forward-looking city, but also one that dotes on relics of past glories. During a recent visit, I was shown a place I’d heard about, but wasn’t sure existed. Its history is tied up with that of the American theatre, but it also gave its nickname to at least one movie, a 1923 silent drama starring Claire Windsor. And it shows up for real in Woody Allen’s Hannah and Her Sisters, when Allen’s character, attempting to convert to Catholicism, attends a concert on the premises. The official name for the Little Church Around the Corner is the Church of the Transfiguration. It’s an Episcopal parish church, built in 1849, that still enjoys a prime piece of real estate on East 29th Street, between Madison and Fifth Avenues. Long associated with liberal causes, it provided sanctuary to endangered African Americans during the Civil War Draft Riots of 1863. But its enduring nickname arose in 1870, when theatre professionals were considered morally suspect. After the death of an actor named George Holland, a fellow thespian, Joseph Jefferson, appealed to the rector of a nearby Manhattan church to conduct a funeral service for his deceased friend. The rector turned him down, but suggested, "I believe there is a little church around the corner where they do that sort of thing." From that day to this, the Little Church Around the Corner has had a warm relationship with the acting community.

This connection between the church and the Great White Way can be seen throughout the charming building. One stained-glass panel puts Jesus front and center, but also sneaks in, at bottom, a small image of Joseph Jefferson in his once-famous portrayal of Rip Van Winkle. There’s also an impressive stained glass image of Edwin Booth, once known as the Prince of Players for his many classic Shakespearean portrayals on the American stage. (The brother of, John Wilkes Booth, Edwin never quite lived down the stain on his family’s honor. Following his death in 1893 at Manhattan’s Players Club, his quarters still remain undisturbed.)

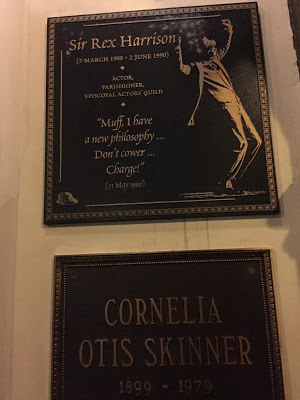

Theatre folk memorialized with plaques in the church sanctuary include Minnie Maddern Fiske (1865-1932) and Cornelia Otis Skinner (1899-1979). The latter, daughter of matinee idol Otis Skinner, was a special favorite of mine. As a successful actress, biographer, and comic essayist, she did it all. Our Hearts Were Young and Gay, a memoir she co-wrote with journalist Emily Skinner about their youthful travels in Europe, became a best-seller, then inspired several films, two Broadway shows, and a short-lived TV series. Another honoree is actor Rex Harrison. Though I hardly associate this hard-drinking Englishman with church attendance, he served as an officer of the Episcopal Actors’ Guild, and the Little Church Around the Corner was the site of his memorial service in 1990. His plaque bears an image of him, dancing up a storm, in his most famous role, that of Professor Henry Higgins in My Fair Lady.

Tribute to Edwin Booth

Tribute to Edwin BoothFinally let me mention comic writer P.G. Wodehouse, who as a young English novelist and lyricist made his home in New York’s Greenwich Village. He married his wife Ethel in the Little Church Around the Cormer in 1914, then went on to set many of his fictional weddings at the church. The finale of the hit Broadway musical Sally, which he wrote with Jerome Kern and Guy Bolton, contains a musical tribute to the "Dear little, dear little Church 'Round the Corner / Where so many lives have begun, / Where folks without money see nothing that's funny / In two living cheaper than one.”

Rex Harrison as Professor Henry Higgins

Rex Harrison as Professor Henry Higgins

Published on July 19, 2019 10:00

July 16, 2019

Moe Berg: Pitcher vs. Catcher, Spy vs. Spy

The mystery of Moe Berg is not one that will be solved anytime soon—if ever. Berg (1902-1972) was a Jewish-American baseball player known less for his athletic prowess than for being the so-called “brainiest guy in baseball.” A gentleman and a scholar, he graduated from Princeton, magna cum laude, with a degree in modern languages. It’s said he’d studied seven languages (including Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit), and spoke several of them fluently. While playing professional ball he also earned a Columbia University law degree.

In Casey Stengel’s words, Berg was “the strangest man ever to play baseball.” But play he did, from 1923 to 1939, ending up as a catcher with the Boston Red Sox. In the off-season he traveled abroad, taking classes at the Sorbonne and developing the habit of reading 10 newspapers daily. He also appeared three times on a popular radio quiz show, Information, Please, dazzling listeners with his extensive knowledge of etymology, while refusing to answer any questions about his personal life.

But the most remarkable period of Moe Berg’s career came during World War II (though the facts weren’t divulged until decades later). In 1943 he joined the OSS, the forerunner of today’s CIA, and was sent on secret missions supporting the Allied cause. As an American and a Jew, he faced huge risks while traveling in Nazified Europe under false papers. His most dangerous moment came in 1944 when he was sent by his OSS superiors to meet the Nobel-Prize-winning German physicist Werner Heisenberg. The goal: to ascertain whether the Nazis, under Heisenberg’s leadership, were in process of building an atom bomb. Before his trip, Berg was given a pistol and orders to shoot Berg if the development of the bomb seemed imminent. He was also handed a cyanide tablet in case he was captured.

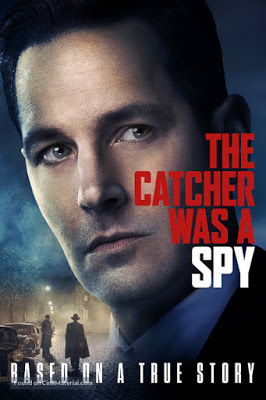

The drama of Berg’s meeting with Heisenberg became the centerpiece of a 2018 film, The Catcher Was a Spy, based on Nicholas Davidoff’s book of the same name. I had looked forward to seeing it, because I’ve interviewed its director, Ben Lewin, regarding his best known film, The Sessions. That very small, very poignant drama—a true story about how a young polio survivor who needs an iron lung happily loses his virginity to a sex surrogate—received much public acclaim as well as an Oscar nomination for Helen Hunt. I was less a fan of Lewin’s next film project, Please Stand By, in which Dakota Fanning plays a runaway girl with autism and a grand passion for Star Trek. (I admit, though, that a scene wholly in Klingon, between Fanning and a sympathetic police officer, works its magic.)

Lewin has a true affinity for misfits, and I was impressed to see how the scope of his most recent project has broadened. The Catcher Was a Spy, beautifully filmed in the Czech Republic and elsewhere, features such screen luminaries as Tom Wilkinson, Sienna Miller, Jeff Daniels, Guy Pearce, and Paul Giamatti. Paul Rudd, normally known for comic and romantic roles, gets to stretch as the enigmatic Berg. The film’s main problem, I believe, is that it builds to a dramatic climax, and then can’t deliver. But I certainly look forward to seeing what Lewin does next.

This film and the book from which it derives both posit that Berg was a closeted gay man. Aviva Kempner’s new documentary, The Spy Behind Home Plate, is skeptical of that approach to the mysterious Berg, given the results of her own research. I haven’t yet seen her film, but a movie-loving colleague of mine attests to its power.

A tip of my imaginary hat to my filmgoing buddy, Susan Henry.

Published on July 16, 2019 09:30

July 12, 2019

“That Damned Elusive Pimpernel” Swashbuckles Again

When I was small, one of my favorite movies was the Danny Kaye classic, The Court Jester. Though Kaye’s physical and verbal antics (“The pellet with the poison’s in the vessel with the pestle”) were hilarious, I never quite understood a major plot point about restoring to the English throne an infant-heir with a peculiar birthmark. Just what was a purple pimpernel, and what was it doing on the baby’s bottom?

As my parents explained, this was a witty nod to the Scarlet Pimpernel, the secret mark denoting the hero of an historical romance set during the French Revolution. The Scarlet Pimpernel (the title refers to a common wild flower) started out as long-running British stage play, by a certain Baroness Orczy. Before long it was turned into a series of novels, starting in 1905. Naturally there were soon cinematic adaptations. The very first, from 1917, starred Dustin Farnum, the silent-movie star who years later became the namesake of a certain Dustin Hoffman. The best known Scarlet Pimpernel film was the first talking version, from 1934. A sumptuous, though sometimes stilted swashbuckler, it stars Leslie Howard, Merle Oberon, and Raymond Massey, under the direction of Harold Young.

Here’s the deal: in 1792 France people’s heads are being chopped off with gay abandon, as the crowd (made of up singularly unattractive individuals) cheers the falling blade of Madame Guillotine.. Clearly we’re supposed to be on the side of the “aristos,” who dress and speak much better. In particular we sympathize with the courageous de Tournays, who have just been condemned to death. Someone dressed as a priest shows them a passage in his Bible: surprise! Inside, there’s a message marked with the insignia of a red flower. The mysterious league of the Scarlet Pimpernel is coming to their aid. Soon they’re spirited out of Paris in a cart driven by a feisty old lady—who turns out to be none other than the Pimpernel himself, in one of his clever disguises.

Actors love to play dual roles, and in this film Leslie Howard has a doozy. He’s the “damned elusive Pimpernel,” who sneers at danger and lives to serve those in need, And he’s also Sir Percy Blakeney, British baronet. On his home turf, he covers his tracks by assuming the languid airs of a fop, one who is obsessed with good tailoring and seems most concerned about the amount of starch in his jabot. The big complication is that he has a wife, a gifted French actress named Marguerite St. Just, who doesn’t know about his secret identity. As played by the lovely but not especially talented Merle Oberon (sorry!), she struggles to understand her husband’s mixed feelings for her. Ultimately, of course, all becomes clear—and she finds herself in the usual female position of needing to be heroically rescued before the final fadeout. Howard, though, seems to be having a marvelous time, ricocheting between the persona of the odious English dandy and that of the heroic man of action.

For me a revelation was the performance of Raymond Massey, the Canadian actor best known for his Oscar-nominated 1940 performance as our 16th president in Abe Lincoln in Illinois. Fans of early television also remember his six-year stint as the venerable Dr. Gillespie in Dr. Kildare. Those two roles are the reason I tend to think of Massey in heroic terms. But as the wily Chauvelin, Robespierre’s envoy to England, he exudes a sinister charm, one that nearly ensnares poor Marguerite. As a French snake in an English garden, he’s certainly fun to watch.

Published on July 12, 2019 10:00

July 9, 2019

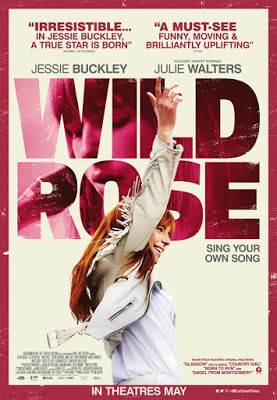

“Wild Rose”: Three Chords and the Truth

Yahooo! Rose-Lynn’s been let out of prison (where she was sent because of a small problem involving a package of heroin). There’s fringe on her leather jacket, a rebel yell on her lips, and an ankle-monitor underneath her cowboy boot,. After a quick stop at the country-music bar where she used to serve drinks and front the local band, she heads for home, but her re-appearance after a year away doesn’t exactly spark joy. Sounds like the makings of a country song.. But this isn’t Nashville. Nope, it’s Glasgow, Scotland.

In the appealing new slice-of-life drama called Wild Rose, Jessie Buckley plays a young woman so vibrant that you can’t help rooting for her even when she’s making a hash of her life, She’s quick to fight, quick to blame others for her own mistakes. (In her mind, her incarceration is entirely the fault of the judge who sentenced her.) Most egregious, she’s all too ready to break the promises she’s made to her two young children (tellingly named Lyle and Wynonna) when these get in the way of her dreams of music stardom in America.

There are some creaky elements to Rose-Lynn’s story, most of them involving a would-be benefactor played by the charming but unlikely Sophie Okonedo.. Post-prison, Rose-Lynn comes to work for this wealthy lady of leisure as a housekeeper, putting her musical ambitions on hold in a bid to lead a responsible adult life.. But soon, once Okonedo’s Susannah discovers the singing talents of her feisty new “daily woman,” she offers to play fairy godmother for Rose-Lynn’s dream trip to Nashville. Of course the trip eventually happens—but not in the way we would expect, and with a far different outcome. It’s a treat, though, to see the awe on Jessie Buckley’s face as she stands on the stage of the “Mother Church” itself, Nashville’s timeless Ryman Auditorium. One of the film’s many pleasures is a chance to catch a glimpse of Nashville, the world’s Music City, while also introducing us to the more low-key attractions of workaday Glasgow.

Rose-Lynn may blossom in the company of the kindly Susannah, but the real key figure in her life is her down-to-earth mother, Marion, played by the always capable Julie Walters. It’s she to whom Rose-Lynn turns for emergency childcare, and for the hard-earned nuggets of wisdom that she’d really rather not hear. Marion can be tough on her only child, but she’s also her biggest supporter, one who understands that Rose-Lynn will need to grow up in an emotional sense before she can earn the opportunities that may someday be waiting for her. It’s ironic that in the last few days I’ve been learning about Anzia Yezierska, a novelist so determined to devote herself to her craft that she literally wrote her young daughter out of her life for many years, letting the child be raised by an ex-husband and erasing her from her own autobiography. That’s what some artists -- both male and female -- do in order to pursue their careers unhindered by family responsibility. But Marion’s not one to let that happen, and her down-to-earth goals and Rose-Lynn’s soaring ambitions make for a powerful combination.

Understanding the thick Glasgow accents in this film sometimes makes for a challenge. But the soundtrack is splendid indeed, featuring the voices of some of Nashville’s finest female singers, and also Jessie Buckley’s own powerful pipes. Her character has tattooed on her arm the classic description of country music as Three Chords and the Truth. Wild Rose has convinced me of the wisdom of that sentiment.

Published on July 09, 2019 10:00

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers