Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 66

July 4, 2019

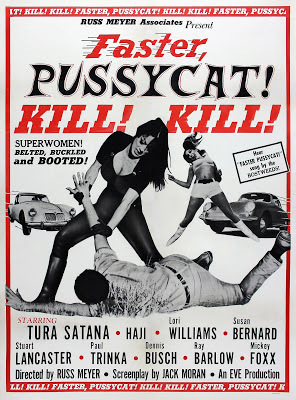

What’s Faster, Pussycat? (An All-American 4th of July Gorefest)

If I hadn’t worked for Roger Corman for so many years, I probably wouldn’t be a fan of Faster, Pussycat1 Kill! Kill! This is a movie that has the great Corman virtues: it’s fast-paced, it’s concise, and it packs a wallop. To be clear, this is not a Corman film. It was shot in 1965 by exploitation king Russ Meyer, who also concocted the original story, what there is of it.

In terms of personal style, Russ Meyer can almost be considered the anti-Corman. Roger in his prime projected the aura of an English professor or a hip minister. Meyer, a combat cameraman during World War II, was a self-proclaimed man among men, who was married three times but seemed most at home hanging out with his old military buddies. Clearly turned on by tough, sexy women with oversized breasts, Meyer in film after film indulged his personal obsessions, once saying, “I don't pretend to be some kind of sensitive artist. Give me a movie where a car crashes into a building and the driver gets stabbed by a bosomy blonde, who gets carried away by a dwarf musician.”

Before he passed away in 2004, Meyer directed 29 films, with titles like Mudhoney, Supervixens, and Wild Gals of the Naked West. In 1970, at a time when camp was flourishing, he was actually hired by Twentieth Century Fox to shoot a relatively big-budget film, Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, as a follow-up to Fox’s crowd-pleasing Valley of the Dolls. (Roger Ebert, a Russ Meyer devotee, wrote the script.) But Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! remains the closest Meyer has come to making a classic. The story, such as it is, involves three tough, sexy young women (with, natch, oversized breasts) who are out seeking thrills in the California desert. Stumbling upon an innocent young couple, they make short work of the guy and abduct his female companion. Then there’s a crippled old man who has a hidden cache of money as well as a mentally disabled son. What happens thereafter is not pretty, though good triumphs over evil at the very end.

Among the cast, the standout (in more ways than one) is the witchy and bosomy Tura Satana, whose exotic looks and background led her to a career as an exotic dancer (and, it is said, a romance with Elvis Presley). Trained in martial arts, she is frequently given credit for supplying many of the film’s best lines and visuals. Both before and after her death in 2011, Satana inspired homages of many sorts. In the film, her #1 victim, young Linda, is played by the sixteen-year-old Susan Bernard, whose protective mother had the challenge of watching over her on the set. It’s Bernard’s death on June 21 of this year (after a long career in B-movies) that has encouraged me to return to her very lurid debut film. . Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill, shot in black and white on a $45,000 budget, was not successful when it opened, but it quickly became an exploitation classic. Though initially critics (other than Roger Ebert) were scornful, many have come around. John Waters, in typically over-the-top fashion, has said the film is “beyond a doubt, the best movie ever made. It is possibly better than any film that will be made in the future.” There are still frequent references to it within pop culture,. On The Simpsons, for instance, an Itchy & Scratchy cartoon is titled Foster Pussycat! Kill! Kill! It took a reviewer on IMDB to give it the perfect accolade: “the Citizen Kane of trash cinema.”

Published on July 04, 2019 09:30

July 2, 2019

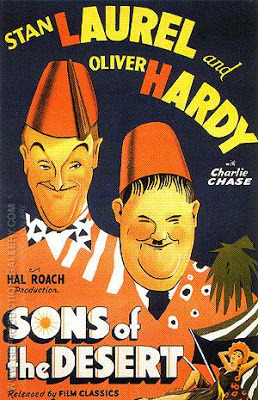

Laurel and Hardy: Another Fine Mess

A fat man and a skinny one, the best of friends, sharing pratfalls and adventures. How delicately they danced together; how impishly they snuck away from wives and authority figures to pursue their own kind of fun. It sounds kinky, when I put it in those terms, but I’m really acknowledging how Laurel and Hardy, the greatest comedy duo in Hollywood history, captured the spirit of overgrown boys in their films. Whether they’re appearing in silent shorts or full-length talkies, their humor is so fresh that a seven-year-old of my acquaintance roared with delight when watching their antics on the big screen.

The occasion was a screening sponsored by the Los Angeles Conservancy, as part of its invaluable Last Remaining Seats series. The conservancy annually puts on several programs, featuring some of Hollywood’s greatest treasures, in the grand old movie palaces that still stud Broadway in Downtown L.A. The Orpheum Theatre, a Beaux-Arts beauty erected in 1926, was once a vaudeville showcase. That’s why it boasts a Mighty Wurlitzer organ, which was very much in evidence during the screening of a 1927 Laurel and Hardy short, ”The Battle of the Century.” This nineteen-minute gem, which was long considered lost, features the slim but flabby Laurel as a hapless prizefighter and the hefty Hardy as his manager. This film starts with a parody of the famous Dempsey vs. Tunney “Long Count” fight, but then memorably culminates in the world’s biggest and most elaborate pie fight, with thousands of cream pies flying through the air and landing on everyone within range, including a guy opening wide in the midst of a dental procedure.

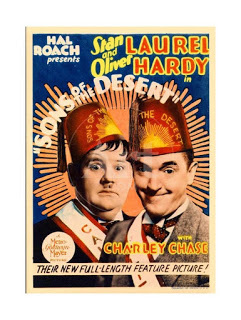

After we’d survived the pie fight (and made mental notes to stop for dessert later), the feature attraction came on. This was the 1933 Sons of the Desert, in which the two buddies are fez-wearing lodge members determined to sneak out on their respective spouses to attend a rowdy convention in Chicago. As always, Laurel is the bumbling innocent and Hardy the crafty con artist. They’re also next-door neighbors who always seem to be popping up in each other’s living rooms, much to their wives’ disgust. In order to sneak away from home (and later sneak back), there are hijinks involving feigned illness, a pretend-doctor, some tiptoeing around their houses’ common attic, and a dramatic plummet into a rain-filled barrel. This is not the film in which they perform their famous soft-shoe terpsichore(that’s Way Out West), but it has charm and yuks galore.

Last fall a feature film based on the later years of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy made its debut. Stan and Ollie, featuring a perfectly-cast Steve Coogan and John C. Reilly, depicts the two on what turned out to be their final tour of the British Isles, circa 1953, long after their Hollywood celebrity had waned. Their brand of humor no longer fit the cinematic trends of the time, and Hardy’s ill health made every performance touch and go. Yet, heroically, they kept at it, delighting their British fans. Stan and Ollie isn’t much of a movie, but it gives a convincing portrait of two aging titans of comedy. That final dance routine, in which Ollie’s worsening condition has the audience holding its collective breath, is not easy to forget. Nor did Laurel forget Hardy easily. A crawl at the film’s end tells us that after Ollie’s death in 1957, Stan flatly refused to take on another partner. He spent the last eight years of his life creating unusable comic routines for himself and the buddy he could never forget.

Published on July 02, 2019 09:18

June 28, 2019

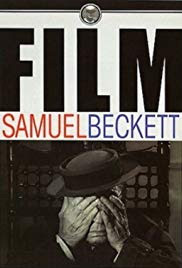

Samuel Beckett: Finding Not-So-Happy Days at the Movies

Last weekend my husband and I saw a big-deal production of Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days, staged by James Bundy, the estimable dean of the Yale School of Drama. In the extraordinarily difficult central role, two-time Oscar winner Dianne Wiest was both luminous and heartbreaking, and the physical production could not have been faulted. And yet. And yet. Afterward, my spouse, who knows full well how I like to work my playgoing and filmgoing experiences into blog posts, mentioned that he doubted I’d soon be blogging about Beckett. As always, I’m happy to prove him wrong.

Beckett’s play, which well befits a master of the Theatre of the Absurd, takes place entirely on a bleak dirt mound, which I couldn’t help associating with global warming run amok. To make matters even more ominous, in the first act Wiest’s chatty Winnie is buried up to her waist in dirt. She can gab away; she can greet the day with a smile and a luxurious stretch of her arms; but she can’t leave. Then there’s Act Two: now Winnie is encased in dirt up to her neck. Only her head protrudes to try to find some small crumb of joy in her surroundings. In the long-winded Act One, I admit I got sleepy, though Beckett’s play is so dreamlike (or nightmare-like) that moving in and out of a doze somehow seems like an appropriate response. During Act Two, I stayed fully awake, and the play as a whole left me with a lot to ponder.

Of course no Samuel Beckett play should be taken literally. The 1969 Nobel laureate, author of such classics as Waiting for Godot and Endgame, viewed the human condition with a kind of comic nihilism that has no appeal for many audiences (my long-suffering spouse included). I remember hearing, though, that a traveling production of Godot, in which two tramps bicker while waiting fruitlessly for an important figure who never arrives, was greeted with awed attention at one performance. These particular playgoers were prison inmates, and they knew exactly the mangled emotions—and the feeling of endless, pointless waiting--that Beckett was trying to project.

Always one to experiment, Beckett sometimes revealed in his plays a strong interest in human interaction with machines. Though he died long before the Age of the Internet, he liked to keep abreast of technological advances. A notable example is 1958’s Krapp’s Last Tape, a short play in which a single character, a man in his sixties, interacts with tapes of his own voice recorded thirty years earlier. And, unlikely as it may seem, Beckett also aspired to direct films, racking up 12 credits for staging short works for the camera. He made his first movie, simply called “Film,” in 1965, with the great Buster Keaton in the silent central role. I’ve heard that Keaton had no idea what the filmmaker was after, but he knew how to take direction, and the result is mesmerizing. In the seventeen minute black-&-white film, Keaton is seen almost entirely from the rear, enveloped in a heavy black coat, his trademark porkpie hat planted firmly on his head. He scuttles down a wintry urban street as if pursued, and enters his shabby flat where whatever it is he fears still seems to be coming after him. A sense of doom infuses every frame, and Keaton’s mastery of his physical self allows us to share the dread he’s feeling., though an interlude involving two cats is extremely funny. Tension builds, until finally the impending horror stands revealed. But maybe you’d better see it for yourself.

Published on June 28, 2019 11:16

June 24, 2019

The Subject Was Rape: How Hollywood Tries to Make a Difference

In recent weeks, Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us, has been the talk of Hollywood. And why not? This four-part documentary series funded by Netflix gives faces to the five young men of color who were wrongly convicted of taking part in the brutal rape of a female jogger in New York’s Central Park in 1989. The case, which involved police coercing the accused into false confessions, is widely considered one of the great failures of the American judicial system. Members of the so-called Central Park Five served up to 15 years in prison for crimes they hadn’t committed. Clearly this was a travesty of justice.

In recent weeks, Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us, has been the talk of Hollywood. And why not? This four-part documentary series funded by Netflix gives faces to the five young men of color who were wrongly convicted of taking part in the brutal rape of a female jogger in New York’s Central Park in 1989. The case, which involved police coercing the accused into false confessions, is widely considered one of the great failures of the American judicial system. Members of the so-called Central Park Five served up to 15 years in prison for crimes they hadn’t committed. Clearly this was a travesty of justice. A new book by my colleague Christopher Johnston outlines another kind of travesty, this one involving victims of rape and sexual assault. In Shattering Silences: Strategies to Prevent Sexual Assault, Heal Survivors, and Bring Assailants to Justice, Chris uses all his journalistic skills to explore the ways our society has let down rape survivors. It’s still all too common for police officers and defense attorneys to treat rape victims with cold skepticism, implying that these women (through their dress and behavior) had encouraged the vile acts perpetrated on them, that they were somehow “asking for it.” Fortunately, a coalition of law officers, sociologists, district attorneys and others has made great strides in introducing new standards of care for rape victim and new strategies for putting their assailants away for good.

One key recent discovery has come from Dr. Rebecca Campbell, a professor of psychology at Michigan State who has done considerable research into what she calls “the neurobiology of trauma.” Campbell has clinical proof that for a person facing sexual assault, fight or flight are not the only possible responses. It’s also perfectly natural for the victim to freeze, totally incapable of resisting an assailant. That’s why a woman under duress may not fight back, and why her inability to summon up the details of the assault for investigating officers does not prove that she’s being untruthful.

Chris’s book is filled with the profiles of men and women, mostly in Cleveland and Detroit, who’ve made great advances in helping rape victims. Many of them have been impelled by their own personal histories to come to the aid of others suffering from sexual trauma. Partly this involves learning to handle victims with kindness and respect, especially during the invasive procedure required in the preparation of sexual assault kits. What’s outrageous to learn is that these kits, which contain crucial DNA evidence capable of putting a rapist behind bars, are in many jurisdictions ignored for decades. In Detroit, for instance, the current push to provide state-of-the-art services for rape victims began with the discovery, in 2009, that 11,341 kits were crammed into a warehouse, unprocessed.

Hollywood movies and television shows have done their share of rape-related stories. Often cheap sensationalism is involved (yes, I worked in the B-movie industry). But back in 1988 Roger Corman alumnus Jonathan Kaplan made The Accused, a film that takes seriously the plight of a woman who’s raped by some goons in a barroom. Jodie Foster won an Oscar for her gutsy performance as a rape survivor who fights back. Even more interesting to me is the fact that Mariska Hargitay, the longtime star of TV’s Law & Order: Special Victims Unit, has been inspired to take on the plight of survivors of sexual assault, as well as abused children. Her Joyful Heart Foundation, established in 2004, is an active part of a push to test all backlogged rape kits, nationwide. See http://www.endthebacklog.org/ for more info.

Published on June 24, 2019 10:11

June 21, 2019

"Late Night": Rancor in the Writers’ Room

It’s not easy being the only “girl” in the room. That’s what Mindy Kaling faces when, she lands on the writing staff of a big-name late-night talk show. In the film Late Night, Mindy plays Molly, an eager-to-please young woman who just happens to walk through the door after the show’s host decrees that the next hire be female. (Being brown doesn’t hurt either.) So there she is, an obvious diversity hire, surrounded by white males who are convinced she has nothing to offer.

I admit I felt her pain. It took me back to when I, as a very young PhD, nabbed what seemed like a dream job, a tenure-track position at a major university. I wasn’t exactly the sole woman present at my first faculty meeting: there were two elderly females who’d been there for years and were considered part of the furniture. But my introduction to my new colleagues could have been better. The chairman of my department, noting that I’d worked in the film industry, gave me “credit” for not only writing and overseeing but also appearing on screen in porno films. (Hey, Roger Corman flicks may have their T&A moments, but they hardly qualify as porn!.) .Everyone eyed me curiously. I should have realized then that my days as a serious academic were numbered.

Of course we in the audience know, when Mindy is reduced to sitting on an overturned wastebasket because no one will grant her a chair, that eventually she’ll prove her mettle. (The fact that the plucky Kaling wrote this film and served as one of its producers is a guarantee that she’ll land sunny-side up.) But the big boss whom everyone hates and fears is not some alpha male. Instead it’s Emma Thompson as Katherine Newbury, a late-night host who’s one part Ellen DeGeneres (cropped hair and tennies) and one part prima donna. She may come across on the tube as friendly and fun, but behind the scenes Katherine is a true dragon lady, snapping at her staff, firing folks left and right. Part of this, of course, may be insecurity: her show, popular for years, has seen a steep ratings decline, and she’s just been informed by the network head (yes, another woman) that she’s destined for the chopping block.

It’s remarkable, really, how many words there are in the English language for pushy females. I’ve just used a few of them: prima donna, dragon lady. And of course there’s the B-word. Interesting how many movies I can think of in which a female boss deserves these epithets. See Sigourney Weaver (who steals other women’s bright ideas) in Working Girl. And, of course Meryl Streep as the diva of all divas, Miranda Priestly, in The Devil Wears Prada. In each case a likable newcomer (Melanie Griffith, Anne Hathaway) has to get past an older female who grants her no respect. That’s Kaling’s role too, but Thompson’s Katherine is not simply an ogress who has to be taken down a peg. We see enough of her to learn her admirable traits: high intellect, a respect for quality in all its forms, enough self-knowledge to realize that she hasn’t lived up to her own lofty ideals.

As Katherine’s husband, John Lithgow reveals the side of her that few people see. In last year’s The Wife, another great mature actress, Glenn Close, played a role in which her spouse won the accolades she herself deserved. Catherine’ musician husband, diminished by Parkinson’s, is glad to grant her the spotlight. He only wants—as Kaling’s Molly wants—her to be her very best self.

Published on June 21, 2019 12:34

June 18, 2019

How Franco Zeffirelli Taught Us About Love

See below for the 1936 poster

See below for the 1936 posterWhen I think about the late Franco Zeffirelli, the lush romantic music of Nino Rota enters my head, my mind flies back to the year 1968, and I’m once again young and in love. Of course I’m thinking of one of Zeffirelli’s earliest and best films, Romeo and Juliet. Over a long career much of his most acclaimed (not to mention most controversial) work involved opera, Nonetheless I think Zeffirelli’s opulent touch was extraordinarily well suited to the filming (within the walls of medieval Italian towns) of Shakespeare’s great early tragedy. .

When, as a college student, I first watched Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet, my reference point was the classic 1936 black-&-white version from MGM. As befit one of Irving Thalberg’s prestige projects, the cast was chockful of stars from the MGM stock company: John Barrymore as Mercutio! Basil Rathbone as Tybalt! Edna May Oliver as Juliet’s nurse! Even Andy Devine in the small comic role of the nurse’s servant! Young Romeo was played by not-so-young Leslie Howard, who at 43 was still a go-to guy for romantic leading roles. His Juliet was 34-year-old Norma Shearer, a demure beauty who just happened to be Mrs. Irving Thalberg. It’s by no means a bad film, but under the direction of George Cukor the actors are formal and a bit stiff, playing at the Bard with a capital B. There’s no way that anyone of my generation would have connected emotionally with this story of long-in-the-tooth star-crossed lovers. It was something we could watch dutifully, as for an assignment in an English class.

Then in 1968, at a time of high emotion for the youth of America, along came Zeffirelli to transform the time-worn story. Yes, the settings were beautiful and the well-choreographed street brawls unmistakably alive. But what really sold this version was the decision to cast in the leading roles actual teenagers not far removed in age from the lovers in Shakespeare’s tragedy. Leonard Whiting was 18 years old when the film was released, while Olivia Hussey was 15, just two years older than the storied Juliet. Their shaggy hair and youthful impetuousness made them seem like our peers. At a time when we were discovering love, sex, and the fact that our parents weren’t always right, their on-screen passion struck a chord with Baby Boomers. (I’ve since learned that the movie’s morning-after scene, with a nude Whiting artfully stretched out on the coverlet of the bridal bed, came as a delightful shock to certain young men who thereby discovered their own sexual leanings.)

One last example of how Cukor and Zeffirelli’s approach differed: Romeo first espies Juliet as she dances at the Capulet ball. In that instant, his infatuation with a certain Rosaline fades away as he reverently murmurs, “Oh, she doth teach the torches to burn bright!” In the Cukor version, Romeo is watching a formal dance number in which Juliet, framed by a symmetrical arrangement of handmaidens, sways prettily while (as I recall) holding a floral wreath. Zeffirelli shows us instead a huge circle of Capulets, all shapes and sizes, all happily executing the moves of some period couple-dance. Juliet is not the best dancer of the bunch, and the dance formation doesn’t set her off as a rare object, or a prima donna. But she’s young, she’s lovely, and she’s just the right age . . . so of course Romeo falls in love on the spot. .

It’s the youthful exuberance of love that Zeffirelli shows us. Perhaps the film may not hold up today, but what youthful love affair does?

Published on June 18, 2019 11:49

June 14, 2019

Facing Life (and Death) in the ‘Hood: The Hate U Give

High school, the movies tell us, is Hell. High school is a place where boys, pushed in unfamiliar directions by puberty, vie to prove their machismo. Being labeled a geek, a jock, or a brainiac hardly makes life easy. And girls face their own special challenges. Puberty strongly affects them too, as does the feeling of needing to fit into a social clique. Recent flicks like Lady Bird and this year’s Booksmart explore the mixed-up psyches of high school girls. Looking back a bit, we could call this a genre, and include on the list such high-school-set movies as Heathers (1998), Mean Girls (2004), and Easy A (2010), all of them focusing on smart young women trying to figure out their place in the world.

The girls in these movies face boy problems, best-friend problems, too-smart-for-her-own-good problems. But Starr Carter, the girl at the center of The Hate U Give, has problems of a much more life-and-death kind. At age 16, she’s just seen a close childhood friend needlessly gunned down by a cop at a traffic stop. And six years earlier, when she was only ten, another best friend died in a drive-by shooting. Such is life, we’re told, when your skin is black and you live in what most people call the ghetto.

Starr’s parents, Big Mav and Lisa, highly value their ethnic roots. They’ve chosen to make their home where they grew up, in Garden Heights, a place they consider (despite the gangs and the drug dealers) a genuine community. Still, out of concern for their children’s welfare, they’re now bypassing the local public school to send the kids to Williamson, a posh suburban academy. That’s where Starr learns the fine art of code-switching, shifting her home-grown speech patterns so that her classmates are never reminded of her inner-city origins. As she explains in the voiceover that continues throughout the film, the white kids love using black phrases and intonations, because “slang makes them cool. Slang makes me‘hood.” That’s why the uniform-wearing preppie she calls Starr Version 2.0 is not comfortable sharing with her school friends the trauma she’s just experienced, even though news of Khalil’s death has rocked the city and she herself has been asked to testify in front of a grand jury probing the police officer’s conduct. .

The Hate U Give (the title comes from a Tupac Shakur lyric) is based on a Young Adult novel that’s been an international best-seller since 2017. The novel, by Angie Thomas, presents a wide social panorama that includes ghetto thugs, yuppie suburbanites, good-hearted elders, and a black cop who serves as the Carter family’s alternate father-figure. Family dynamics are complicated. Starr’s dad -- of whom she lovingly says, “You set an example of what a man should be” -- has a prison record and is raising a child he fathered with a woman who’s now in thrall to the local gang lord. Perhaps because of the novel’s huge success, the filmmakers have stayed largely faithful to the source material, to the point that a casual viewer will surely be confused by the intricacy of the relationships on display.

A few big changes have been made, though. That Grand Jury scene is shot impressionistically, for greater impact, with the dead boy appearing as a ghostly presence in the jury box. Starr’s parents, in the film version, never abandon Garden Heights, despite the retaliation they face from gang-affiliated hoodlums. And a key moment featuring Starr’s younger brother vividly drives home Tupac’s point: "The Hate U Give Little Infants Fucks Everybody." It’s a thought worth considering.

Published on June 14, 2019 15:31

June 11, 2019

Tap-Dancing Around TV on the Tonys

This past weekend, Broadway celebrated itself with the annual Antoinette Perry awards. Although, in this era of streaming and binge-watching, no televised awards show can hope to capture the Nielsen ratings it once enjoyed, for the viewing public the Tony shindig is still the most entertaining of the bunch. Partly this is because those savvy Tony folks give out their less exciting awards during commercial breaks, so that we at home never have to sit through the honoring of the year’s best sound designer or lighting maven. And each host is carefully selected on the basis of sparkling personality, musical talent, and for being a familiar living-room presence. For years, Neil Patrick Harris was the go-to Tony host, and he made an amusing cameo appearance in 2019. Lin-Manuel Miranda has also ably taken on the job. But in 2019 the role of the MC went to the ebullient James Corden, who nimbly presided over the festivities on the gargantuan Radio City Music Hall stage.

The Tony event, needless to say, is always a celebration of the joys of live theatre, as epitomized by Broadway. In fact, Corden’s splashy opening number emphasized the fact that “This is live! . . . We are alive!” In other words, part of the excitement of Broadway (ideally, at least) is its freshness, its spontaneity, its sense that anything can happen. (Of course there are also drawbacks: cramped theatre aisles, iffy air conditioning, rude seatmates, an endless line to the ladies’ room at intermission.) Award-winning actors are always insisting that the theatre is their true home. Still, it remains true that many of Broadway’s brightest stars spend most of their time on the tube. See, for instance, the great Audra MacDonald (currently a regular on The Good Fight) and Laurie Metcalf (The Conners), as well as Corden himself. Though this jolly Brit was first introduced to America in 2011 as the Tony-winning star of an updated Italian farce, A Man and Two Guvnors, he is today known and loved by millions for hosting The Late Late Show, home of both “Carpool Karaoke” and the even wackier “Crosswalk the Musical.”

Because TV is his bread and butter, it makes sense that Corden’s opening number amusingly tap-danced around the love-hate relationship between the stage and the screen. “We’re much better than television,” he said at one point. In the next breath, he and his fellow thespians quickly pointed out some exceptions to this statement: Game of Thrones, Fleabag, Mrs. Maisel, Big Little Lies. And so on, and so on. Eventually, Corden was forced to admit the truth: “We love you, TV . . . you pay us so much more.”

This being so, it was no fluke that some of the nominees in major categories were movie and Tv personalities, whose box-office clout could help their stage shows to thrive. Among this Best Actor candidates were two genuine Hollywood stars appearing in theatrical versions of beloved movies. Jeff Daniel was cited for playing the Gregory Peck role in To Kill a Mockingbird. (Yes, I know it was a novel first.) And Bryan Cranston, the ultimate Tony winner, took on the part made famous on screen by Peter Finch, that of the half-crazed news anchor in Network, he who’s “as made as hell and . . . not gonna take it anymore.” Leave it to smart producers to understand that the ticket-buying public prefers familiar faces and familiar plot lines. And, in some cases, familiar costumes. Like the va-va-voom outfits that brought 80-year-old Bob Mackie a Tony for this year’s The Cher Show. Yes, we’d seen them before.

Published on June 11, 2019 12:41

June 7, 2019

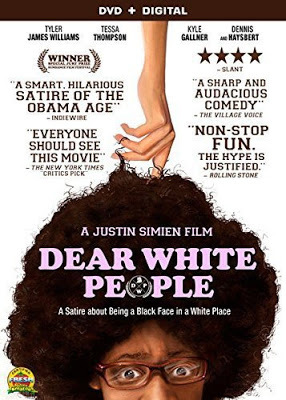

Tessa Thompson Addresses “Dear White People”

Poster mocks white folks' fascination with black hair

Poster mocks white folks' fascination with black hairThese days it’s hard to keep track of Tessa Thompson. Her image seems to be everywhere: on billboards advertising the new Men in Black: International; on the tripartite cover of Vanity Fair, draped alongside other rising stars in a red dress to die for. I picked up a recent copy of Time saluting “Next Generation Leaders,” and there she was in a dramatic solo cover photo. Inside Tessa was given a full-page interview that probed her views on sexuality, race, and filmmaking, labeling her “an activist first, an actor second.”

Not bad at all for the perky young lady who used to hang out with my son after drama class at Santa Monica High School. She always had a personality to reckon with; now she’s entering the celebrity pantheon.

Tessa has recently been seen as an earnest young activist in Selma, as the girlfriend of the boxer in the Creed films, as the flawed superhero Valkyrie in Thor: Ragnarok, and as the outside-the-law star of a small indie, Little Woods. She also registered strongly on TV’s Westworld series. She seems to have roles galore coming up, including a stint voicing the top dog in a remake of Disney’s Lady and the Tramp. (Who knew?) But her breakout role was that of Samantha (“Sam”) White in Justin Simien’s 2014 satire of race relations at a tony liberal arts college, Dear White People.

I just re-watched this film recently, and found it delightful. It’s very much a product of the Obama era—the knucklehead president of Winchester College feels comfortable announcing that “racism is over in America”—but the issues it comically broaches are, alas, still with us today. What makes Dear White People so funny is the fact that virtually everyone (students, faculty, administrative staff) is essentially a hypocrite. The president may talk about educational goals, but he’s really fixated on sucking up to wealthy alumni. The dean (solemnly played by the invaluable Dennis Haysbert) is most concerned about his ongoing rivalry with the president. The campus militants ready to protest racism at every turn all seem to have ulterior motives too: one young Asian woman who hangs with the Black Student Union instead of supporting her own ethnic group explains, “You guys got better snacks.” Nor does the film overlook other campus types, like the misfit nerd, the future politician (who would really be happier as a comedy writer) and the “bougie” black chick relying on her “good hair” to get her the attention she craves. As for the most obnoxious of the white kids, the ones who gleefully promote a party mocking black stereotypes, they’re too pleased with themselves to be anything but jerks.

Tessa’s role is one of the few that filmmaker Simien regards with some sympathy. As Sam, a student filmmaker whose “Dear White People” radio show is broadcast all over campus, she’s famous for her feisty take-downs of white assumptions. Her intensity is her hallmark. Someone says of her that “Spike Lee and Oprah had some sort of pissed-off baby.” But Sam’s got her secrets too, like a sympathetic white boyfriend who knows her favorite movie maven is actually not Spike Lee but Ingmar Bergman. It’s not until late in the film that we discover why she fights so hard to assert her blackness. This revelation confirms the film’s intelligence. Simien goes far beyond the outrageous hijinks of most college-based movies, drawing his various plot strands together to help us see something real about today’s campus life. And gives us a whole lot of laughs along the way.

(No, that’s not Tessa on the poster, but here she is on her TIME cover.)

Published on June 07, 2019 10:06

June 4, 2019

We Like Short Shorts (The Academy’s Nominees for Best Animated Short)

Long airline flights can introduce you to the unexpected. Flying to New York City last month, I discovered via my seatback videoscreen the five Oscar-nominated short animated films of 2018. Animated shorts—those that are not attached to a Pixar blockbuster—are generally overlooked by the moviegoing public. That’s a shame, because the best of them are clever and artful, doing a lot with a little. While cruising at 30,000 feet, and waiting for the snack mix to arrive, I discovered what I had been missing at my local cineplex.

Here are a few things I learned from the class of 2018: Despite the advent of computer-generated animation, hand-drawn cartooning is not dead. Canada is the home of some very creative animators. Asian motifs and connections often prevail. The relationship between parent and child is a popular subject for animated shorts, as is the whole notion of the passage of time. And though several of these films are voiced by actors, a cartoon can convey a good deal without saying a word.

In alphabetical order, the first film up is Canada’s “Animal Behaviour,” a deliriously wacky hand-drawn saga set in a therapy session. The shrink is a dog, and the patients are all members of the animal kingdom, like a pig with an eating disorder and a praying mantis who understandably has relationship issues. Things move along predictably until a gorilla lumbers in, at which point chaos erupts.

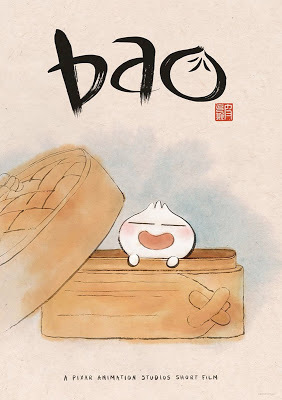

Next comes “Bao,” a Chinese-Canadian entry with Pixar connections. Silently showing an amiable little woman who (yes, really!) adopts one of her homemade dumplings as a baby, then watches it evolve into the teen years and young manhood, this film has much to say about the joys and heartbreak of being a mom.. I saw “Bao” as a prelude to Disney and Pixar’s Incredibles 2. For me this eight-minute masterpiece was far better and certainly far more touching than the highly-touted feature film. Though I doubt Pixar’s target kid-audience would grasp the point, their parents certainly should . No wonder “Bao” took home the statuette on Oscar night.

Probably my least favorite of the films was “Late Afternoon,” a lovely-to-look-at story of an elderly lady moving back and forth through her memories as she’s served cookies and tea. Predictable? I should say so. Lugubrious? That too.

Almost as touching as “Bao” is “One Small Step,” about a Chinese American girl who yearns to become an astronaut and walk on the moon. Helping her along her path is her father, a humble shoemaker, who keeps her appropriately shod as she grows, matures, and moves toward the faraway surface of her dreams. The use of shoes as a motif works beautifully in giving new meaning to Neil Armstrong’s famous words. At the ending, you may shed a tear or two. I did, anyway.

Finally, there’s another poignant and aesthetically challenging Canadian film, “Weekends,” about a young Toronto boy shuttling between the very different homes of his divorced mom and dad. This film draws on the boy’s perspective, at times showing the parents’ new love interests in a grotesquely surrealistic light. Once again the animation is hand-drawn; once again no words are spoken out loud, so that we’re forced to supply our own subtext for the story. But “Weekends” is by no means completely silent (as I first thought because my headset plug had detached from its socket.) The film is scored to the evocative strains of Gymnopédies, No. 1 by Erik Satie. At fifteen minutes in length, “Weekends” eventually outwears its welcome, but its artistry still lingered as I moved through the clouds.

Published on June 04, 2019 13:39

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers