Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 57

May 8, 2020

“Child of Light”: The Hollywood Adventures of Novelist Robert Stone

One day my boss, low-budget moviemaker Roger Corman, asked me to look through an anthology of price-winning short stories and come up with a young master of prose fiction who might be converted into a screenwriter. Years before, he had given a similar assignment to my predecessor, Frances Doel. In the pages of Esquire, she had discovered a young man named John Sayles. Eager to try his hand at filmmaking, Sayles wrote Corman’s Piranha, then evolved into the award-winning writer/director of indie films like Lone Star.

Hoping for comparable success, I set my sights on Madison Smartt Bell, whose short story about a film editor convinced me he’d be willing to explore a transition to Hollywood. He was hired to write the screenplay for a disaster film we were calling Aftershock. Let’s just say it didn’t turn out well (partly because Roger had developed a sudden fascination with political infrastructure issues, and insisted these be at the center of our earthquake drama). No hard feelings: Madison and I stayed in touch, and he’s since turned out a long series of highly-praised novels and biographies, with a particular focus on the history and landscape of Haiti.

Now, he’s just published an intimate and comprehensive biography of a literary idol who became a close friend.. Robert Stone, perhaps best known for the National Book Award-winning Dog Soldiers, published eight novels, beginning with 1967’s Hall of Mirrors. Stone’s fiction covers a wide range of territory, both geographically and emotionally, but he was one of our greatest chroniclers of what might be called the Vietnam War generation. His troubled, amoral characters reflect Stone’s own restless life. Madison Bell’s new Child of Light; A Biography of Robert Stone both probes the fiction in depth and links it to Stone’s own psychological complexities.

I was especially fascinated by Stone’s forays into Hollywood to adapt two of his novels into screenplays. At first it must have seen easy. As Stone’s ever-loving wife Janice told Madison, “There was the book already, with all the dialogue. How hard could it be.?” I was thoroughly gratified with Madison’s response: “Harder than one might think, in fact—good screenwriting is a more demanding endeavor than it looks to people who haven’t tried it.”

Stone himself, after being hired by Paul Newman to adapt Hall of Mirrors into what became WUSA, remembered that “the thing in progress slide between incoherency and the nearest equivalent cliché. The novel aspired to a certain poetry and was made of words.. The movie WUSA came out looking like such a novel rendered as a very indifferent episode of Matlock.” Clearly, the involvement of Newman, Joanne Woodward, Anthony Perkins, Lawrence Harvey, and director Stuart Rosenberg (coming off of Cool Hand Luke) couldn’t save the project, which ended up as a massive critical and box-office flop.

In 1976, Stone tried again, adapting the complex, haunting Dog Soldiers for director Karol Reisz and actor Nick Nolte. The result was a 175-page screenplay (far too long by the standards of Hollywood, which considers each page a minute of screentime). The draft immediately set off alarm bells because, faithful to Stone’s own novel, it portrayed its female lead (Tuesday Weld) as a willing participant in a drug deal instead of an innocent dupe. Refusing to make this key change, Stone walked out on the screenwriting gig, but did take the opportunity to visit during the location shoot in Mexico. Dog Soldiers, inexplicably retitled Who’ll Stop the Rain, was another bust. But the experience gave Stone insights into the entertainment industry, leading to 1986’s Children of Light. Looking forward to reading that!

Published on May 08, 2020 14:51

May 5, 2020

White Makes Right: “The Plot Against America”

Right now, with state governors being accused of Nazism for not allowing the opening of gyms and hair salons in the midst of a health pandemic, The Plot Against America seems timely indeed. This six-part HBO miniseries, based on a 2004 novel by Philip Roth, wrestles with the idea of real Nazis and with powerful Americans all too ready to ally with them to achieve their own hateful goals.

Right now, with state governors being accused of Nazism for not allowing the opening of gyms and hair salons in the midst of a health pandemic, The Plot Against America seems timely indeed. This six-part HBO miniseries, based on a 2004 novel by Philip Roth, wrestles with the idea of real Nazis and with powerful Americans all too ready to ally with them to achieve their own hateful goals.We’re all familiar by now with Quentin Tarantino’s playful reshaping of our twentieth-century past. In Tarantino’s hands, Adolf Hitler is assassinated and Sharon Tate emerges unscathed from the Manson murder plot. These are films that relieve us—for the moment—from the burden of history by showing us that real-life horror has a happy outcome. The Plot Against America goes in the opposite direction, starting with a happily middle-class Newark family, circa 1940, and positing the rise of a fascist ideology that puts their hopes and their very lives in danger.

The linchpin of all this in Roth’s novel is the unexpected election of “lone eagle” Charles Lindbergh over Franklin Delano Roosevelt for the presidency. Lindbergh, the airline pilot who became a national hero for his solo trip across the Atlantic, is well known to have harbored anti-Semitic views and to have sympathetic feelings for the German high command. (He also, in later decades, secretly fathered seven children by three different German women while remaining married to Anne Morrow Lindbergh—but that’s a story for another day.) Running on an anti-war platform that favors a friendly alliance with Nazi Germany, President Lindbergh puts in place an “America First” regime that looks down on immigrants and their offspring, and is all too quick to use race-baiting to sow domestic discord.

The Levin family—husband, wife, and two young sons—are proudly Jewish and proudly American. (In his novel, Roth chose to give them the first and last names of his own family members and settle them all at his own boyhood New Jersey address.) They admire Lindbergh’s achievements, but are leery of him as a political figure. Not so one of the story’s most enigmatic characters, Rabbi Bengelsdorf (John Turturro), who through a combination of personal vanity and misguided belief is sure the Lindbergh presidency will be a glorious one, in which he has personally been tapped to play a key role. His marriage to Bess Levin’s idealistic sister Evelyn (Winona Ryder) puts the Levin family at the center of the drama, when they are “selected” to move to Kentucky as part of a new federal program designed to absorb them more thoroughly into the American fabric. Of course, as Rabbi Bengelsdorf fails to see, its long-range implications are ominous for anyone who deviates slightly from the American mainstream. (Kentucky, where kindly farmers co-exist with the Ku Klux Klan, does not exactly come off well.)

As fascistic impulses rise in the United States, tensions pit cousin against cousin and father against son. A powerful moment near the end involving sisters Evelyn and Bess (a deeply sympathetic Zoe Kazan) shows what can be accomplished in a scene that triumphantly passes the so-called Bechdel Test: two women talking together about something other than a man. Writers David Simon and Ed Burns (The Wire) have been deeply faithful to the work of Roth, who consulted with them at the beginning of the project. But, as conveyed in a fascinating podcast about the making of the series, they go Roth one better in figuring out how to end their drama. It’s election day in America, and we can all share the shivers that date implies.

Published on May 05, 2020 13:35

May 1, 2020

“The Crown”: It’s (Not So) Good to Be the Queen

If you have to commit to social isolation, Buckingham Palace might be the place to do it. After all, it’s very well decorated, there are plenty of loyal retainers on hand to attend to your every need, and if you are inclined to mope, you have many comfy corners to choose from. Running out of toilet paper is doubtless not a problem. I trust Queen Elizabeth II, now 94 years old, is being duly cautious, sheltering herself from threats of COVID-19 either at Buck House or at one of her several other homes in England and Scotland. But she did emerge on April 5 (see below) to speak to the people of the British commonwealth from Windsor Castle, urging Britons to stay strong in the face of global pandemic. Her warm, calm, sympathetic tone—far different from the bombast of various politicians familiar to us all—was widely praised. It seemed that in her sixty-seven years on the throne she has learned to bridge the gap between her royal self and her subjects., at least when the chips are down.

As I suffer through my own isolation right now, I’m binge-watching all three seasons of The Crown, the Netflix series that is astoundingly frank about the comings and goings of the British royal family. I have no way of knowing if all the scandalous details of this regal soap opera are portrayed accurately, if the love affairs, emotional kinks, and threatened coup d’états really happened in the ways they show up on screen. Still, I’m old enough to remember some of this from contemporary news reports,, like the Profumo scandal and all the sturm und drang involving Princess Margaret falling more than once for exactly the wrong guy.

The series also allows us to see the queen (Claire Foy in the early years, Olivia Colman later) slowly and sometimes painfully learning the tricks of her very particular trade. If Queen Elizabeth has now mastered how to speak to her subjects, we’ve seen her (particularly in a long-ago address to striking Welsh miners) so detached from the lives of the working class that she rouses their hostility against her. And slightly later, when there’s an unspeakable tragedy involving children in another Welsh village, we’ve watched her struggling to appear sympathetic when her eyes are dry. As TV drama, it’s absolutely irresistible.

One detail that fascinates me about The Crown is the fact that in some ways it’s a TV drama about the impact of television on British royalty. It seems that when Elizabeth, then age 26, was crowned Queen in Westminster Abbey, she appointed her husband, Prince Philip, to the head of the committee working out the details of the coronation. For her this selection was mostly made to appease a restless spouse whose ego was suffering from all the veneration surrounding his wife. But Philip, bucking centuries of tradition, came up with some useful modern ideas. Prime among them was the concept of including Elizabeth’s subjects in the ceremony by putting the whole event on live television. This attempt at slightly democratizing the royal pomp and circumstance turned out to be a major p.r.. success story. But Philip’s later insistence (inspired in part by Jacqueline Kennedy’s televised White House tour) on a day-in-the-life documentary look at the royals at work would became a major embarrassment for all concerned. In any case, it’s clear that the whole royal family relies heavily on TV for their view of the outside world. Amid Buckingham Palace’s elegant sofas and tapestries, they gather around the box to watch Parliamentary election results and astronauts walking on the moon.

Published on May 01, 2020 10:18

April 28, 2020

Stephen Sondheim: A Little Zoom Music

Stephen Sondheim, the composer-lyricist of musical theatre masterpieces, is far more associated with Broadway than with Hollywood. Still, as “the other Steven” (Spielberg) acknowledged on last weekend’s Zoom Sondheim tribute, Sondheim surpasses even Spielberg himself in his passionate devotion to Golden Age movie trivia. He’s even an Oscar winner, for contributing a song, “Sooner or Later (I Always Get My Man),” to 1991’s Dick Tracy. And he’s the co-screenwriter, with actor Anthony Perkins, of The Last of Sheila, a 1973 non-musical film based on their mutual love of twisty murder mysteries.

So Sondheim’s definitely a movie fan. He’s become an active part of what might be considered Hollywood heresy: an upcoming remake of the classic 1961 West Side Story, for which Sondheim once wrote the lyrics to Leonard Bernstein’s score. He also authorized the filming of respectable versions of two of his biggest hits. The delightfully macabre Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street was filmed in 2007. Directed by Tim Burton and starring Johnny Depp and Helena Bonham-Carter, the film version lost some of the stage show’s vocal richness but added some bizarre touches that Sondheim must have enjoyed. (I loved the staging of the “By the Sea” number, showing Sweeney on the sand at Brighton, still wearing his rusty black city clothes and dour expression.) And in 2014 there was a thoroughly delightful Into the Woods, Sondheim’s most fractured of fairy tales. A work of astonishing musical complexity, it reveled in the singing talents of such familiar Hollywood folk as Emily Blunt, Anna Kendrick, James Corden, Christine Baranski, and Meryl Streep.

The latter two showed up on that Zoom tribute, which celebrated Sondheim’s 90th birthday while raising funds for Actors Striving to End Poverty. Baranski and Street were joined on screen by Audra McDonald, all of them socially distancing, to get happily sloshed while warbling Sondheim’s acerbic “Here’s to the Ladies who Lunch,” from Company. I loved watching the three in their plush white bathrobes, wielding cocktail shakers like maracas, trying desperately to sing together while being far, far apart. There was also a foursome striving to bring off “Someone in a Tree” from Pacific Overtures, with one of the performers getting in character by recording his vocal from under a kitchen table. And somehow thirty musicians, led by a hardworking conductor, managed to coordinate on the jazzy overture from Merrily We Roll Along.

It’s always a delight to hear Sondheim songs—both the familiar and the obscure—belted out by Broadway pros like Sutton Foster, Neil Patrick Harris, Kelli O’Hara, and Bernadette Peters. I also enjoyed change-of-pace performers like the wacky YouTube star Randy Rainbow, perhaps better known for his timely “Spoonful of Clorox” spoof of a certain political leader. And it was a pleasure to learn that Hollywood’s Jake Gyllenhaal really can sing.

Of course it’s no secret that non-singers have been starring in Hollywood musicals for years. At first secrecy surrounded the fact that Marni Nixon’s limpid soprano provided the singing voices for Deborah Kerr in The King and I, Audrey Hepburn in My Fair Lady, and Natalie Wood in The Side Story. Nowadays the trend is for performers to use their own pipes, however modest their vocal talent. Sometimes their limitations are a blessing in disguise. When Sondheim was first writing A Little Night Music, star Glynis Johns had a limited range. He kept this in mind while writing one of his best-loved ballads, “Send in the Clowns.” But when the play made a transition to film, Johns’ role was given to glamorous but not particularly musical Elizabeth Taylor, with painfully uncinematic results.

Published on April 28, 2020 12:09

April 24, 2020

Not Just for the Money: Hollywood Screenwriters Tell All

When I fell into the movie industry, no one taught me anything about how to write a screenplay. I was an almost-PhD in English, accustomed to reading Shakespeare and abstruse modern novels. On my first day at Roger Corman’s New World Pictures, I was handed a script – it was Charles Willeford’s screen adaptation of his own down-and-dirty Cockfighter – and told to note my thoughts on how well it worked. Somehow I managed to make a good impression. My career as a motion picture story editor had begun.

Roger, in those years, was a master at avoiding the hiring of union screenwriters, who of course were paid more than Corman peons. My good friend Frances Doel, from whom I learned the tricks of the screenwriting trade, was quite resigned to being send home on a Friday afternoon and told to come back Monday with the first draft of some screenplay for which Roger had supplied the premise. She’d slap a pseudonym on the title page, and when a credentialed screenwriter was brought in to improve on her very rough original, the identity of the first writer was our little secret. (We had to come clean just once, when the very gentlemanly William W. Norton expressed a strong interest in meeting with that original writer in order to check out some story points.)

Later, when I worked at Roger’s Concorde-New Horizons, we dispensed with WGA writers altogether. Or, at least, we weren’t WGA signatories. Plenty of writers with guild-worthy credentials but no work on hand were happy to invent new names for themselves so that they could be part of our cut-rate productions. Henry Dominic, anyone?

Although I have six Roger Corman screenwriting credits, I’ve never been a WGA member. Still, the guild sends me the occasional check (compensation for overseas screenings of films I’ve written), and I have the greatest respect for the pros who deserve every penny they’ve earned by crafting my favorite movies and TV shows. And I’m happy to endorse a recent publication of the Writers Guild Foundation, edited by screenwriter Daryl G. Nickens. It’s called Doing It for the Money: The Agony and the Ecstasy of Writing and Surviving in Hollywood.

How-to books about screenwriting are a dime a dozen, and I wouldn’t recommend this one as a primer. Though several brief sections offer the reader “Secrets of the Hollywood Pros,” the book’s strength does not lie in providing specific advice on such things as formatting and loglines. Instead, the core of Doing It for the Money is a series of short essays by award-winning writers on how they’ve handled their own yen to tell stories on the screen. They’re writers, after all, so they express themselves with heart and wit. They’re funny, and often inspirational.

My very favorite section is by Glenn Gordon Caron. He was once a newbie on a TV sitcom writing staff, led by a man named Steve. Everyone loved Steve’s work, but one week it was Caron’s turn to churn out the first draft. Instantly, the cast turned hostile, refusing to have anything to do with this interloper’s script, and insisting that Steve step in and fix it. Steve, who knew a good script when he saw one, told Caron to re-submit the same draft but add the word “revised version” to the title page. Suddenly everyone was onboard, and Steve announced that Caron had made many of the great fixes himself. With his reputation and his morale saved, Caron went on to a long career, including the wonderful Moonlighting. Like most Hollywood writers, he wasn’t doing it just for the money. .

Published on April 24, 2020 18:17

April 21, 2020

Hiding in Plain Sight: “The Two of Us”

As (thanks to the COVID pandemic) we self-isolate from the outside world, it’s easy to compare ourselves to Anne Frank and her family, sheltering in that tiny attic. Big difference, of course: the Franks and others like them were hiding from human enemies, who’d be glad to ship them off to death camps if they ever showed their faces. The distinction between a virus and a flesh-and-blood foe is obvious. Viruses don’t care who gets in their way. Humans choose their victims, selecting some, letting others go on with their lives, untouched. During the dark days of World War II, the revelation of who you were could mean your death at the hands of someone who hated you solely because of the accident of your birth.

These thoughts occurred to me at a timely moment: tomorrow is a day set aside to remember the victims of the Holocaust,. A slew of Holocaust movies, from both American and European filmmaker make clear what social isolation is REALLY like. One that was released back in 1967 comes from France. Claude Berri’s The Two of Us is striking because it’s a Holocaust film without death camps and without serious violence. In fact the world it shows us is for the most part fairly pleasant.

It’s 1944, and a Jewish family living in Paris under the Vichy regime is having a hard time keeping a low profile. The Langmanns’ nine-year-old son Claude is a mischievous boy who always seems to be getting into minor trouble. For his own protection, and theirs, his parents reluctantly ship him off to live in the countryside with the elderly father of a friend. They’ve schooled him to take on a new surname, to pretend to be Roman Catholic, and (above all) never to let anyone see him unclothed from the waist down.

Pépé Dupont, whom Claude quickly learns to call Grandpa, is a man of the soil. He’s so uncouth and so earthy that Zorba the Greek would seem like a suave urbanite by comparison. Claude’s first glimpse of him occurs at his kitchen table, where he’s feeding his large elderly dog with a spoon. Pépé (memorably played by the award-winning Michel Simon) has a good heart: alone among those in his community he’s become a vegetarian, rather than eat any of the beloved rabbits he and his wife raise. But if he loves animals, he’s less sure about people. He hates many of them on principle: the Communists, the English, the Americans. Above all, he has no use for Jews, whom he pictures in terms that might have come straight from a textbook for Nazi children. Jews, he insists, are easy to smell out. Claude of course keeps silent about his own background, and soon he and Pépé are enjoying a warm familial relationship.

If this were an American movie, there’d be, toward the end, a big revelation scene in which Claude’s masquerade would be uncovered and lessons would be learned. Instead The Two of Us ends on an ambiguous note: we’re simply not sure if Pépé ever becomes aware of the deception, nor do we know the extent to which Claude’s “innocent’ questions about Jews are asked with an ulterior motive. Frankly, I liked the way the film left me with matters to ponder. One of them is the fact that Claude Berri, making his directorial debut, was born to Jewish immigrant parents and named Claude Berel Langmann. In 1944 he was nine year old. This film doesn’t claim to tell HIS story, but he surely knew in his bones the world he showed on screen.

Published on April 21, 2020 13:37

April 17, 2020

Hildy’s Game: “His Girl Friday”

“Molly’s Game,” which I watched while flipping through Netflix offerings, is a 2017 feature based on the real-life story of Molly Bloom. No, not the earth-mother figure in James Joyce’s Ulysses. This Molly Bloom is a former champion skier, one who was derailed by a freak accident from her quest to join the U.S. Olympic ski team. Looking for challenges in warmer climates than her native Colorado, she decamped to L.A., where she soon found herself shepherding a high-stakes celebrity poker game. Though not a gambler herself, she was soon risking her reputation and her legal standing in order to keep raking in a small fortune in tips.

It’s a fascinating story, though one I couldn’t always follow. And I’m still not exactly sure what the film was trying to say. A corny scene between Jessica Chastain’s Molly and her psychologist dad (played by the always earnest Kevin Costner) didn’t strike me as helpful. Was his attempt to explain her life-choices in analyst-speak meant to seem astute, or oblivious?

In any case, the film was the directorial debut of writer Aaron Sorkin, known for his screenplay for The Social Network as well as such stellar TV as The West Wing. Those who are familiar with Sorkin’s work know that his characters are smart, sassy, and speak very fast. More than one review of the film, which earned an Oscar nomination for Sorkin’s screenplay, mentioned that its characters deliver their lines as if they were part of the cast of His Girl Friday. Exactly! This sparkling Howard Hawks film from 1940 is set not in a high-price gambling den but in the world of journalists and daily newspapers. The cast, led by Cary Grant as editor-in-chief Walter Burns and Rosalind Russell as ace reporter Hildy Johnson, speak their lines at a breakneck pace, as though the fate of the world depends on what they have to say. And perhaps, in a way, it does. Though the portrayal of newsmen in the film is hardly sugar-coated—they’ll do just about anything to scoop the competition—there’s still the sense that the news they deliver is important, that the fate of a city (if not the world) hangs on the stories they uncover. Brutal competition is part of the game, and sometimes they may happen to get their facts wrong. But this hardly means they’re manufacturing Fake News. Theirs is an honorable profession, and Rosalind Russell’s Hildy is the best of the best.

The complication is that she’s Walter Burns’ ex-wife, and is on the brink of marrying a much more sedate type, an Albany insurance man played by Ralph Bellamy in the usual Ralph Bellamy role. (Who knew that 20 years later he’d leave behind his boring-nice-guy image by portraying FDR in Sunrise at Campobello?) Walter wants Hildy back, both as an ace reporter and as a wife, and a dramatic jailbreak by an accused murderer arouses her passion for newsgathering just in the nick of time. You can guess how it all ends.

His Girl Friday was based on a hit play of the era, Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur’s The Front Page. The play is an effective melodrama, climaxing with the jailbreak. In adapting it for the screen, someone had a bright idea. Since it featured a newspaper editor trying to hang onto his star reporter, why not make that reporter a ballsy female, as well as the editor’s former wife? That brilliant stroke foregrounds the interpersonal story, relegating the murderer’s plight to a secondary role. As always, the battle of the sexes makes for boffo cinema.

Published on April 17, 2020 09:59

April 14, 2020

Springtime for Hitler . . . and COVID-19

None of us want the current pandemic to kill off our sense of humor. Which is why, sheltering at home, I find myself opting to watch old comedies. Some of them, frankly, turn out to be less funny than I remember. I’ve always revered Carol Burnett: there was a time when I considered her variety show (1967-1978) essential weekly viewing. True, some of the sketches are still very funny: I continue to chuckle at the movie parodies, like the Gone With the Wind spoof in which Scarlett—making an elegant green gown out of the plantation’s velvet drapes—forgets to remove the curtain rod, with disastrous results. But I’ve just looked at clips from The Carol Burnett Show’s first season, and found myself cringing at obvious gags, annoying husband-and-wife bickering, and (in a belabored sketch featuring Sammy Davis Jr.) moments poking fun at racial bigotry in a smug, self-congratulatory way.

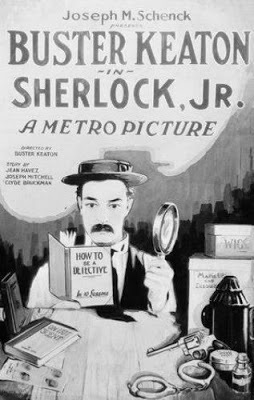

For something completely different I turned to a genuine oldie, Buster Keaton’s silent 1924 romp, Sherlock Jr . Keaton’s perennially solemn face and rubber legs have endeared him to generations of comedy lovers. Sherlock Jr. is not as out-and-out hilarious as The General (in which, during the height of the Civil War, his character commandeers a stolen locomotive and drives it through enemy lines). But this story about a movie projectionist who dreams of being a detective is filled with technical sleight-of-hand that has had a profound effect on Hollywood. Keaton’s leading character seems at one point to disappear into a small suitcase. Elsewhere, there’s a dream sequence in which, while Keaton is slumbering next to his movie projector, a second version of himself rises to leave the booth and then climbs directly into the motion picture being projected. Years later, Keaton (who like most of the early comic stars wrote and directed his own material) confided to film historian Kevin Brownlow that "every cameraman in the business went to see that picture more than once, trying to figure out how the hell we did some of that."

A few nights later, after watching a Mel Brooks documentary, I sought out Brooks’ very first feature, The Producers. Brooks by 1967 had made a name for himself as one of the zany writers on Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows, as the portrayer of the 2000-Year-Old Man, and as the creator of TV’s Get Smart. His move into movies began with the overtly bizarre idea of a musical celebrating “Springtime for Hitler.” Eventually he launched a story in which an over-the-hill Broadway producer (Zero Mostel) and a babe-in-the-woods accountant (a young Gene Wilder) conspire to raise money for the worst musical ever produced. The logic is that if the show flops bigtime, they can keep the funds they’ve raised. Of course it becomes a huge hit, and they’re royally screwed.

In 2001 the film (which won fans but garnered mixed reviews) became a genuine Broadway musical, a Tony Award winner starring Nathan Lane and Matthew Broderick. Normally movies that are made into stage plays tend to lose their charm and their essence. But in this case the stage version (also written by Brooks) corrected a lot of structural flaws in the original. The long first section of the film—the bonding of the two leading men and their search for a “creative” team—is hilarious. But the film gets derailed when Dick Shawn, as an LSD-addled hippie Hitler-portrayer, bounds in and does his shtick for far longer than we want to watch it. Thereafter, what plot there is falls apart. Brooks in those early years simply didn’t know when to quit.

Insider fact: Dustin Hoffman, a Greenwich Village neighbor of Mel Brooks back in the day, was offered the role of Franz Liebkind, the playwright nostalgic for the glories of the Third Reich. Hoffman eventually turned it down – to star in The Graduate opposite Anne Bancroft. As Brooks was forced to admit, declining a role in The Producers to make love on camera to Brooks’ beloved new wife was—for Dustin Hoffman--a very smart choice indeed.

Published on April 14, 2020 10:58

April 10, 2020

"Unorthodox": Hair Today, Gone Tomorrow

Today I suspect most of us—isolating ourselves at home to escape the Corona virus—have discovered a desperate longing to visit our barbers and hairdressers, Wouldn’t it be nice to settle back in that comfy chair for a wash and a trim? Naturally, I can’t help thinking about movies in which haircuts play a key role.

As a social setting, a hair salon can be an important gathering spot, both in real life and at the movies. The urban black community, in particular, seems to love its barbershops, as seen in a series of comic Barbershop movies, as well as in Eddie Murphy’s Coming to America. The notion of small-town white Southern women looking to the local beauty parlor as the locus of their lives finds dramatic expression in Steel Magnolias, where everyone knows and sympathizes with everyone else’s woes.

Right now, though, we don’t have the luxury of congregating in a world of swivel chairs, mirrors, hot towels, and clippers. Some guys tired of looking Neanderthal might be tempted to explore getting rid of the problem entirely by shaving their heads. As Yul Brynner and Woody Strode once showed us, bald can be sexy—at least if we’re talking about those of the male persuasion.

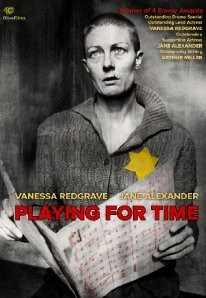

Bald women, though, not so much. It occurs to me that there are many dramatic films which use the cutting of a woman’s long tresses as a climactic moment. There’s something almost unspeakably poignant about watching a woman be transformed by the loss of her locks. Usually such scenes suggest the degradation of a hapless female by those who hold power over her body and her soul. Like, for instance, Nazis. The 1980 TV film Playing for Time is based on the memoir of French-born Fania Fénelon, a Jewish concert pianist who saved her life by performing for her captors in a female orchestra. Vanessa Redgrave was widely considered brave for allowing her hair to be shaved off in order to authentically represent an Auschwitz inmate. More recently, Anne Hathaway, portraying a fallen woman in pre-Revolutionary France, had her dark locks hacked off on camera in 2012’s Les Misérables. Submitting to the brutal shearing helped win her an Oscar for best supporting actress.

Rosemary’s Baby contains a haircut of a different kind. At the beginning of Roman Polanski’s 1968 theological chiller, Mia Farrow’s Rosemary wears her hair longish. But as her difficult pregnancy advances, she gets the bright idea of updating her personal style. When she leaves the beautician’s chair, we see a gaunt young woman with a huge belly and a chic but severe crop of hair (design by Vidal Sassoon) that hugs her face, accentuating her delicate features. More than anything, she looks like a sacrificial lamb ready to be led to the slaughter. (And yes, she also resembles the great Falconetti, whose 1929 silent masterpiece, The Passion of Joan of Arc, puts front and center a young woman with a cropped head and a haunted look. Said filmmaker Jean Renoir in admiration, “That shaven head was and remains the abstraction of the whole epic of Joan of Arc.”)

Recently I watched a four-part Netflix miniseries called Unorthodox, drawn from the memoir of a young woman who broke away from a strict Hassidic community in Brooklyn to start a new life. Just before her wedding day, nineteen-year-old Esty submits to the shaving off of all her long hair. Henceforth, as a married woman, she’ll only be seen in a wig . The on-camera shaving of her head, though done to celebrate a marriage, seems as brutal as a rape.

Dedicated to the memory of Woody Strode Jr. (aka Kalai Strode). All former guides at the U.S. Pavilion, Expo ’70, will understand why.

Published on April 10, 2020 15:31

April 7, 2020

In the Family Way: “Moonstruck”

I wonder what genuine Italian-Americans think of Moonstruck, which in 1987 was a huge critical and popular hit. Do they consider it a charming, heartwarming representation of a vanishing way of life? Or do they cringe at the clichés, annoyed at being presented to the world as superstitious, hyperemotional, in love with food, sex, and opera? Maybe they’re just glad that this fanciful version of life in an Italian section of Brooklyn--while it may boast some (offscreen) lusty coupling and a smidgeon of adultery—contains nary a single Mafioso. Not being of Italian descent myself, I am free to enjoy this fairytale (which, I should note, is based on an Oscar-winning original screenplay by John Patrick Shanley, who is no more Italian than I am).

There is, I should note, a mostly Italian-American cast, featuring Vincent Gardenia as a philandering papa, Broadway avant-garde specialist Julie Bovasso as a lusty aunt, and the late Danny Aiello as a hapless suitor. The leading man is Nicolas Cage, who is actually a Coppola with a name change. But the film’s two performance Oscars were won by women whose kinfolk came from other locales. Cher (born Cherilyn Sarkisian) can claim Armenian descent, and Olympia Dukakis is Greek-American. Well, I guess their Mediterranean roots make them close enough for Hollywood.

At any rate, their characters are definitely people with a well-defined outlook. They strongly believe in luck, mostly bad. (Cher’s Loretta started off her marriage on the wrong foot because there was no church wedding. As a direct consequence, her husband was hit by a bus and died.) Whatever their behavior during the week, these women go to confession on Sunday. They crave romantic rapture, but remain highly suspicious of it: to marry for love is to invite disappointment. Still, there’s always room for the occasional miracle, like the one in faraway Palermo that solves everyone’s problems at the film’s end. So long as that huge round moon hits your eye like a big pizza pie (as in the Dean Martin musical oldie that opens and closes the film), everything will turn out as it should.

You can call this movie a watered-down form of grand opera: the snippet of Puccini’s La Bohème we hear in Moonstruck captures something of the characters’ baroque emotional journeys. Though the operatic performance that’s a key part of the plot takes place at WASP-y Lincoln Center, it tugs directly at the heartstrings of the blue-collar Italians in attendance. (There’s a key moment when Loretta, overcome by her first taste of opera, breaks down her emotional barriers. Her eyes moisten, and suddenly this self-sufficient woman is ready to clutch the proffered hand of someone who loves her This night-at-the-opera trope was stolen, I suspect, by the writers of Pretty Woman, who created a similarly transformative moment for Julia Roberts, in the company of Richard Gere, three years later.)

More than anything, though, Moonstruck is a movie about the unbreakable bonds of family. To cast off (or cast out) a family member is to invite disaster. On the other hand, to bring family together (especially around a dinner table stocked with plenty of pasta and wine) is to usher in God’s grace. At a time when most of us are stuck in self-isolation, sometimes separated by great distances from loved ones, it sounds like a dream come true to be crowded around a table groaning with the weight of good food. Would that this year’s Easter and Passover celebrations could allow for that “all in the family” kind of joy.

Published on April 07, 2020 12:29

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers