Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 55

July 17, 2020

Audra McDonald: Culturus Interruptus

I’m a huge fan of Broadway singer and actress Audra McDonald, who brings passion, nuance, and a peerless soprano voice to every musical role she undertakes. Her long string of Tony Awards recognizes her success in a variety of stage vehicles, everything from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Carousel (where she made theatre history as an African-American Carrie Pipperidge) to Ragtime to Porgy and Bess. She’s been acknowledged for non-singing roles too, notably in a Broadway revival of Lorraine Hansbury’s classic A Raisin in the Sun. I treasure the recordings in which she reveals her sharp timing, her sense of humor, and her affection for the work of new composers, especially women. Now 50, she’s an American treasure.

I’ve several times enjoyed her stage performances. But of course all that’s a thing of the past in this era of COVID-19. We who love live theatre and concerts sadly recognize that it will be a long, long time before we can leave home to get a culture-fix . The Internet, augmented by various technological platforms, can give us an emotional lift by presenting great stars in an up-close-and-personal format. At least, that’s the idea. Unfortunately, just when we’re thinking it’s safe to enjoy ourselves online, technology tends to throw us a curve.

Early in the lockdown, a star-studded live Zoom tribute to Stephen Sondheim had musical theatre buffs counting the minutes to “curtain-time.” (One of many promised treats was McDonald singing a sloshed shelter-in-place version of “The Ladies Who Lunch” with chums Christine Baranski and Meryl Streep.) Alas, grating technical difficulties delayed the opening of the broadcast for at least 45 minutes while we fans lurked around our computers, desperate for the show to start.

Then last weekend I actually paid for a link to an intimate musical tête-à-tête between Audra and pianist Seth Rudetsky , as part of his now-online Seth Concert Series. Rudetsky’s personality may require some getting used to, but he’s a master accompanist, and clearly Audra’s a longtime pal. From their separate homes they performed old songs and new, interspersed with behind-the-scenes stories and easy banter. But . . . midway through the performance (for which I had shelled out $25) of such artful scat as a Streisand-inspired “Down With Love” medley or a breath-taking ballad like “You Are Your Daddy’s Son” (from Ragtime), the screen would suddebkt freeze, leaving me pining for the intricate passage or the last thrilling notes I’d missed. (Happily, the concert organizers gave me a second chance to see the show in its entirety—and it worked!)

As a versatile performer, McDonald has also played a number of film and TV roles, Few, though, have allowed her to sing, and when it comes to meaty parts I’m certain that her African-American heritage has held her back. On the webcast she told a pertinent story dating back to a TV performance of Annie, shot in 1999 as part of The Wonderful World of Disney. She was very pleased to be cast as Grace Farrell, good-hearted secretary to Daddy Warbucks (Victor Garber): she gets rewarded in the last scene with her boss’s proposal of marriage. Then, after the production had wrapped, word came from on high that the marriage proposal would have to go, or risk alienating the Southern markets. The dispirited cast re-assembled on a Saturday (at enormous expense) to re-shoot the scene. Young director Rob Marshall shot one take, quickly and sloppily, and called it a wrap. He knew what he was doing: making it impossible not to choose the original ending. Which—hooray!—proceeded to air with absolutely no furor at all.

Published on July 17, 2020 10:00

July 14, 2020

The Fire Next Time: Fahrenheit 451

When bestselling author Susan Orlean decided to burn a book, she settled on a copy of a Ray Bradbury classic, Fahrenheit 451. Orlean, not normally a pyromaniac (or a book-burner), performed this stunt as part of her research for The Library Book, chronicling the Great Los Angeles Public Library fire of 1986, in which almost a million books were destroyed. Arson may, nor may not, have sparked the cataclysm. When she set Bradbury’s work aflame, Orlean discovered in herself “elation at the fluid beauty of fire, and a terrible fright at the seductiveness of it and the realization of how fast a thing full of human stories can be made to disappear.” Her choice of Fahrenheit 451 for this experiment was apt: Bradbury’s novella, of course, predicts a future society in which books are illegal and must be burned to a crisp. (I’ll be leading a discussion comparing Orlean’s and Bradbury’s works tomorrow evening, as part of Santa Monica Public Library’s annual Santa Monica Reads program. Over Zoom, needless to say. Y’all come!)

When bestselling author Susan Orlean decided to burn a book, she settled on a copy of a Ray Bradbury classic, Fahrenheit 451. Orlean, not normally a pyromaniac (or a book-burner), performed this stunt as part of her research for The Library Book, chronicling the Great Los Angeles Public Library fire of 1986, in which almost a million books were destroyed. Arson may, nor may not, have sparked the cataclysm. When she set Bradbury’s work aflame, Orlean discovered in herself “elation at the fluid beauty of fire, and a terrible fright at the seductiveness of it and the realization of how fast a thing full of human stories can be made to disappear.” Her choice of Fahrenheit 451 for this experiment was apt: Bradbury’s novella, of course, predicts a future society in which books are illegal and must be burned to a crisp. (I’ll be leading a discussion comparing Orlean’s and Bradbury’s works tomorrow evening, as part of Santa Monica Public Library’s annual Santa Monica Reads program. Over Zoom, needless to say. Y’all come!)  Bradbury wrote his novella early in his much-storied career, in 1953. It helped make him famous worldwide. In 1966, during an era of widespread youthful rebellion against the status quo, the story was filmed by François Truffaut, making his only foray into English-language cinema. Truffaut remained largely faithful to the Bradbury text, leading up to the shivery conclusion in which bands of rebels who have committed to memory the great texts of the past wander out into the snowy landscape that is a far cry from the decadent, book-free city. His one big change (intensely disliked by Bradbury) involved the casting of It-girl Julie Christie as both of the book’s two key female characters. At the center of Bradbury’s novel is a fireman, Montag, who discovers in himself the urge to read books instead of burning them. (The movie, much more European than American in feel, casts Oskar Werner in that role.) Early on, Montag finds inspiration in Clarisse, an ethereal neighbor with a great forbidden love for nature and the written word. She’s his dream-girl, but his wife Mildred is a down-to-earth harridan with a closed mind. Mildred feels enthusiasm only for the kitschy mass media doled out by the repressive society in which they make their home. (Apart from the otherworldly Clarisse, women don’t come off well in Bradbury’s novella, serving mostly as mindless shrews and pawns, not as authors or as the quiet rebels memorizing otherwise lost literary works. This is one of many ways in which Bradbury’s sometimes prescient Fahrenheit 451 is also pure 1950s in its mindset.)

Bradbury wrote his novella early in his much-storied career, in 1953. It helped make him famous worldwide. In 1966, during an era of widespread youthful rebellion against the status quo, the story was filmed by François Truffaut, making his only foray into English-language cinema. Truffaut remained largely faithful to the Bradbury text, leading up to the shivery conclusion in which bands of rebels who have committed to memory the great texts of the past wander out into the snowy landscape that is a far cry from the decadent, book-free city. His one big change (intensely disliked by Bradbury) involved the casting of It-girl Julie Christie as both of the book’s two key female characters. At the center of Bradbury’s novel is a fireman, Montag, who discovers in himself the urge to read books instead of burning them. (The movie, much more European than American in feel, casts Oskar Werner in that role.) Early on, Montag finds inspiration in Clarisse, an ethereal neighbor with a great forbidden love for nature and the written word. She’s his dream-girl, but his wife Mildred is a down-to-earth harridan with a closed mind. Mildred feels enthusiasm only for the kitschy mass media doled out by the repressive society in which they make their home. (Apart from the otherworldly Clarisse, women don’t come off well in Bradbury’s novella, serving mostly as mindless shrews and pawns, not as authors or as the quiet rebels memorizing otherwise lost literary works. This is one of many ways in which Bradbury’s sometimes prescient Fahrenheit 451 is also pure 1950s in its mindset.)Feeling that Truffaut had not had the last word about Bradbury’s novella, writer-director Rahmin Bahrani made it a passion project, which he brought to HBO in 2018. In part, his revisiting of the Fahrenheit 451 material is a triumph: his visuals of a nighttime city dominated by neon and huge public video screens smartly brings the Bradbury world into the 21st century. He has cut some the sillier aspects of Bradbury’s novella (the hideous wife, the lethal mechanical hound who pursues our hero), and his images of fire lapping at the pages of famous books (including recent titles by female authors like Toni Morrison) are hard to shake. Unfortunately, his grasp of his characters is less commendable. The crucial relationship between Montag (Michael P. Jordan) and his captain (Michael Shannon) remains ill-defined. And Bahrani feels compelled to introduce as a McGuffin a mysterious device called an “omnis” that provides a hopeful but unlikely ending. Too bad he got fired up but then lost his way.

Published on July 14, 2020 11:17

July 10, 2020

Exit Laughing: A Farewell Tribute to Carl Reiner

I never met Carl Reiner, but I’ve been near-by. After a big-deal screening at the Motion Picture Academy, I sat in a restaurant booth adjoining the booth occupied by Reiner, his wife Estelle (famous for “I’ll have what she’s having”), his pal Mel Brooks, and Brooks’ wife Anne Bancroft. The hearty merriment at that table spilled over to where I sat, to the point where I wanted to tell the waiter, “I’ll have what they’re having!” (So sad that now, in the wake of Reiner’s recent death, Mel Brooks is --at 94–the last survivor of that jolly foursome.)

I never met Carl Reiner, but I’ve been near-by. After a big-deal screening at the Motion Picture Academy, I sat in a restaurant booth adjoining the booth occupied by Reiner, his wife Estelle (famous for “I’ll have what she’s having”), his pal Mel Brooks, and Brooks’ wife Anne Bancroft. The hearty merriment at that table spilled over to where I sat, to the point where I wanted to tell the waiter, “I’ll have what they’re having!” (So sad that now, in the wake of Reiner’s recent death, Mel Brooks is --at 94–the last survivor of that jolly foursome.) Reiner did it all: he was a comic actor, a writer, a director, a producer, a husband, a father, an all-around mensch. In his honor, I’ve just watched three films he directed, starting with the earliest, Enter Laughing. This 1967 flick, based on a Reiner novel that became a Broadway play, features the sweetness, the goofiness, and the Borscht Belt yucks that have marked Reiner’s work ever since. Young Reni Santoni’s role (played by Alan Arkin in the stage version) is that of a nice Bronx kid who pines to be an actor, like his idol Ronald Colman. Though his parents have decreed he should go to pharmacy school, he sneaks away from his machine-shop job to meet a shyster thespian (Jose Ferrer, dripping with pomposity). There’s an hilarious audition scene (see below) in which he triumphs over two other loser-candidates (the young Rob Reiner is one) simply because the impresario’s actress-daughter (Elaine May) finds him cute. The film’s working-class Jewish elements, including the memorable appearance of old vaudevillian Jack Gilford and a lot of schtik about a prayer shawl, seem to tie in to Reiner’s own Bronx upbringing. His debut as a movie director is hardly a polished one, but there’s a real sense of personal investment in this light-hearted trifle.

Reiner’s directorial career was undeniably lifted by his collaboration on four films with Steve Martin. Martin’s comic stock-in-trade has always been his WASP roots. He pokes fun at himself in The Jerk (1979) as Navin, the son of poor but lovable Black sharecroppers. Though too dense to figure out he’s adopted, he’s the one family member with no sense of rhythm, and his favorite birthday treat is a bologna sandwich on white bread with a cellophane-wrapped Twinkie for dessert. Remarkably, when he goes out into the world, his innocent invention of a device for glasses-wearers called Opti-Grab, earns him a fortune. But it all goes down the tubes when his invention turns out to make users crossed-eyed. Carl Reiner has an hilarious cameo as a cross-eyed version of himself, hauling Navin into court as part of a class-action lawsuit.

The Jerk ends with Martin’s character happily dancing up a storm with his down-home family. A ballroom pas de deux also ends perhaps my favorite Martin/Reiner collaboration, the hilarious All of Me. The inspired 1984 pairing of Martin with Lily Tomlin posits that he is a lawyer who’d rather be a musician and she is a dying heiress who plans to come back from the dead via a mystic transmigration of her soul, as arranged by a charming but pixilated Tibetan guru (Richard Libertini). Somehow, Tomlin’s spirit ends up in Martin’s body, with hilarious results. I suspect if these two Steve Martin films were released today, the political-correctness police might come down hard on them, accusing them of cultural appropriation as well as racial insensitivity. But they’re good-natured fun, something we truly need now. Thank you, Carl Reiner, for making me laugh.

Published on July 10, 2020 11:50

July 7, 2020

Unmasking Alexander Hamilton in the (Living) Room Where It Happens

It’s an ill wind, they say, that blows no one any good. As we all live through the enforced boredom of the COVID-19 pandemic, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton is making a mighty comeback in living rooms everywhere. Would-be theatregoers like me had our expensive tickets refunded at the start of quarantine. But in a great trade-off, we can now see the original cast in the filmed version of the stage production, by committing to a month of Disney+.

Normally a filmed play is not something to get excited about. The thrill of live theatre lies in its spontaneity: the fact that drama blossoms right before your eyes. The audience, fundamentally, is part of the show. Some productions capitalize on this fact by staging the action in such a way that the onlookers are personally drawn in. Back in the 1930s, Clifford Odets’ Waiting for Lefty, which culminates in a labor uprising, planted strikers in the audience, the better to shake up the crowd. In 1967, Hair sealed its connection with the young people in their theatre seats by inviting them on stage to dance with the cast, while their parents awkwardly stayed put. The stage version of The Lion King mesmerizes audience members by opening with a animal parade up the theatre aisles.

Hamilton is not the kind of show that relies on such (let’s face it) gimmickry: the actors stay on the stage and the audience stays in its seats. Still, this very pointed re-telling of the birth of the U.S.A. uses such innovations as rap music and the Founding Fathers played by actors of color, all to drive home a point about the revolutionary nature of the great American experiment. Individual performances have generated electric excitement, particularly just after the 2016 election when Vice-President-elect Mike Pence was in the house. Since then, Hamilton has continued to be a hot ticket, particularly among those new to the theatre-going experience. The show’s reach has been so great that when John Bolton, former National Security Advisor in the Trump administration, put forth his tell-all book, he apparently borrowed its title, The Room Where It Happened, from Hamilton’s jazziest tune.

Because Hamilton, in its Broadway staging, has become such a cultural phenomenon, the always shrewd Disney company saw fit to back the filming of the play, planning to release it at cineplexes next year. COVID changed those plans: with all of us currently addicted to TV viewing, it made sense to release the film NOW, as a splashy way to kick off Disney’s new subscription service.

Years ago I graduated from (really!) Alexander Hamilton High School. There was a statue of Alex in our main building, but few of us had much interest in the man himself. In his knee britches and pigtail, he looked singularly boring: all we knew is that he was Secretary of the Treasury (big whoop!) and had the bad taste to die in a duel. Too bad, we all thought, he wasn’t someone exciting, like, say, Thomas Jefferson. In Lin-Manuel Miranda’s rendition, Jefferson is a real sparkplug, though not perhaps someone worth admiring. Hamilton, by contrast is a bastard, an orphan, and an immigrant—who knew? Also brilliant and occasionally very much mistaken.

I saw a road company of Hamilton in Chicago, in the third balcony of an enormous old theatre. I enjoyed it, but felt I was missing the nuances enjoyed by those in orchestra seats. Thanks to a film version artfully photographed (with ten cameras) and edited, I could finally truly see what the historic hoo-ha was all about.

Published on July 07, 2020 13:41

July 3, 2020

“Apollo 13”– Boldly Going Where No Film Crew Had Gone Before

With the 4th of July coming up fast, there can be no better moment to contemplate Ron Howard’s 1995 epic, Apollo 13. At a time of angry partisan divide, it’s encouraging to look back at a point in recent history where the entire country—in fact, the entire world—was on the same page. And when, in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, we’re all despairing about the American way of life, it’s heartening to remember a crisis that turned into a triumph.

You may recall that in April of 1970, three astronauts blasted off from Cape Canaveral, headed for the moon. Unlike the Apollo 11 mission the previous year, this one occasioned no great amount of press coverage. When Neil Armstrong and his two-man crew departed for the lunar surface in July of 1969, the whole world was watching. Armstrong’s slow-motion steps on the moon—the first by any human being—were cheered by virtually everyone in range of a TV set. The Apollo 12 mission in November 1969 was blissfully uneventful, which meant that by the time James Lovell, Fred Haise, and Jack Swigert strapped into their seats in April 1970, few members of the public were paying much attention. Journalists who interviewed the men before their departure questioned whether they were nervous about the number thirteen. True to their training as tough-minded men of science, they all expressed total confidence in their mission and in each other. Little did they know that an on-board explosion would cripple their spacecraft, leading to the very real possibility that they’d never return to earth.

I thought a great deal about Apollo 13 while writing Ron Howard: From Mayberry to the Moon . . . and Beyond. Howard’s film, which I consider a highlight of his long career, points up the many bad omens for those in search of them. Lovell and his crew had been scheduled for Apollo 14, but fairly late in the game were shifted to the earlier mission when astronaut Alan Shepard, returning from medical leave, needed additional training time. Then, three days before the launch, astronaut Ken Mattingly was booted from the crew, over the objections of his teammates, because of exposure to measles. So Swigert was a last-minute replacement, and the film nicely captures the awkwardness between three men (played by Tom Hanks, Bill Paxton, and Kevin Bacon) who were not entirely comfortable with one another.

The script also makes room for the feelings of those on the ground. Marilyn Lovell, wife of Jim, is sympathetically portrayed by Oscar-nominated Kathleen Quinlan as a supportive but anxious helpmeet, trying to juggling her own fears and her responsibilities toward those left behind. Ed Harris was nominated for playing Gene Kranz, who as director of Mission Operations must somehow keep his cool while leading the mission-impossible effort to bring back the stranded astronauts safely.

Some of the film’s strong sense of authenticity comes from the fact that NASA was an integral partner in its production. The space agency, figuring that Americans would not return to the moon for many decades to come, reasoned that this film (based on Lovell’s own memoir, Lost Moon) could be used as an historic record of the near-disaster. NASA therefore provided full access to its documents and facilities, even giving Howard and his three astronauts the unique opportunity to film in brief spurts in the K-135 aircraft (nicknamed the Vomit Comet), used by generations of astronauts to experience weightlessness. I’ll close with high praise for James Horner’s stirring score, and for the film’s poignant reminder that there’s no place like home.

Published on July 03, 2020 12:44

June 30, 2020

“The King of Staten Island”: More Than Skin Deep

Unlike many New York City residents, I’ve actually spent time on Staten Island. Though the island constitutes one of the city’s five boroughs, residents of the Bronx, Queens, Brooklyn, and Manhattan rarely set foot in what is primarily an urban bedroom community, best reached by the picturesque Staten Island Ferry. But the island has its own patois, its own zoo, its own beaches, and even its own (minor league) baseball team, the Staten Island Yankees.

The mixed sense of pride and embarrassment felt by the residents is conveyed in a raucous but sweet new Judd Apatow comedy, The King of Staten Island. It begins with a clutch of layabout buddies not far into adulthood. Their natural topics of conversation include their chances of scoring good dope and the fact they consider their locale a dead end. Says one, “Why can’t we be cool, like Brooklyn?” Gripes another, “We’re the only place New Jersey looks down on.”

Central to this conversation is Scott, whose dream is to open a combination tattoo parlor and restaurant, to be named Ruby Tattoosday. Like the rest of his life, this dream isn’t going anywhere. At age 24, he doesn’t have a real job and lives at home with his widowed mom. Among his friends he riffs about his neuroses and physical issues (ADD, Crohn’s Disease, you name it) and seems to make light of the fact that his father, a local firefighter, died during a rescue mission in a hotel fire when Scott was seven. It’s clear, though, that having a Hero Dad has made his own life seem insignificant by comparison.

Apatow wrote this film along with comedians Dave Sirus and Pete Davidson. Davidson plays the leading role, one that reflects the broad strokes of his own life. He too was raised on Staten Island, has a host of physical and mental issues, and lost a firefighter-dad in the rubble of the World Trade Center. That’s probably why he seems so wholly credible as Scott, a slacker who is both foul-mouthed and funny, both bone-headed and soft-hearted, dumb enough to get involved in a criminal enterprise and yet smart enough to have the potential to move forward. I don’t think it’s an accident that the film’s final scene finds him on that Staten Island Ferry, heading for Manhattan. This isn’t Saturday Night Fever, but still there’s a sense that, given enough love and guidance, he has the potential to move into a healthy adult life.

A first-rate cast handles with gusto the profanity-laced script. It’s good to see Marisa Tomei, once the Brooklyn bombshell of My Cousin Vinny, as Scott’s plucky mother, who finds love in the most unexpected place. When Tomei won a Best Supporting Actress Oscar for her Vinny role critics scoffed, unwilling to recognize the brilliance of her comic performance. Years later she nabbed additional nominations for heavily dramatic roles in The Wrestler and In the Bedroom, but I’m glad the current film makes room for her blue-collar spunk as well as her tender heart. There’s also a wonderfully credible sense of blunt camaraderie among the firemen with whom Scott eventually finds a home away from home. I can think of no better compliment than to say that they all feel very real indeed. And such wry throwaway dialogue as (at an emotional moment), “We don’t have to get all Oprah” helps keep the film’s potential sentimentality at bay.

Anyway, there’s not much place for the sentimental in a film that climaxes in a bizarre tattooing session. Personally, I loathe tattoos, but I loved The King of Staten Island.

A fond farewell to the talented Milton Glaser, to the irreplaceable Carl Reiner, and to the enigmatic Charles Webb, who wrote the novel that became the film The Graduate. More to come!

Published on June 30, 2020 11:57

June 26, 2020

Of Defenestration and Other Deaths: Steve Bing and Joel Schumacher

Movie fans who love a mystery will be salivating over the demise of zillionaire film producer Steve Bing, who was found dead Monday at the base of the Century City residential tower where he had a luxury apartment on the 27th floor. The strong indication is that he leaped to his death. I slightly knew his mother Helen, a gracious lady who was a leading L.A. philanthropist. The fifty-five-year-old Bing was a do-gooder in his own right, pledging funds to charitable causes and giving major support to the Democratic Party. He also had a serious connection to Hollywood. His reported $80 million investment made possible the screen version of The Polar Express, which went on to earn $285 million globally. He was behind the Rolling Stones concert film Shine a Light, directed by Martin Scorsese, as well as a Jerry Lee Lewis album, Last Man Standing.

Nor was Steve Bing just valued for his money. He wrote several films and TV episodes, and directed one, Every Breath. Among his 18 producer credits was a popular action flick, Get Carter. Though he kept a low profile, he made headlines when he was revealed to be the father of the son born in 2002 to British glamor-girl Elizabeth Hurley. Now a man who seemed to have everything, and lots of it, is gone. Suicide, apparently. But why?

There’s no mystery about the death that same day of 80-year-old Joel Schumacher, who succumbed to cancer in New York City. I wasn’t aware until recently that Schumacher started out as a costume designer, beginning with 1972’s adaptation of Joan Didion’s Hollywood novel, Play It As It Lays. He costumed six films in all, including Woody Allen’s futuristic romp, Sleeper. He then transitioned into screenwriting, getting his name on such popular entertainments as Car Washand The Wiz, before making the leap into directing with The Incredible Shrinking Woman in 1981.For the Brat Pack hit St. Elmo’s Fire, he both wrote and directed. Of his early directorial efforts, I’m partial to the spooky charms of The Lost Boys, the teen vampire saga set in picturesque Santa Cruz.

Once Schumacher’s directorial career got rolling, he proved a master at bringing to the screen the tense legal dramas of John Grisham, including The Client and A Time to Kill. He won the hearts of fans with thrillers of all kind (Phone Booth, starring Colin Farrell, is a prime example), and is known for his colorful contributions to the Batman screen franchise. (Yes, he’s the genius behind casting George Clooney in Batman & Robin and adding nipples to the Bat Suit.)

Despite his mass appeal, top critical honors eluded him, though that didn’t stop him from trying. In 2004, he directed a splashy cinematic version of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s stage musical, The Phantom of the Opera. (Its three Oscar nominations were all in technical categories.)

But I want to end here with a nod to one of his earliest films, The Last of Sheila. In 1973 Schumacher designed the costumes for this twisty whodunit. It was written by none other than Stephen Sondheim and Anthony Perkins, both great lovers of puzzles and word games. The story features beautiful Hollywood folk (Richard Benjamin, Dyan Cannon, Raquel Welch among them) cruising the Mediterranean aboard a luxury yacht, all of them somehow connected to a gossip columnist who’d died a year earlier in a hit-and-run attack. Through an elaborate game proposed by host James Coburn, secrets are revealed and it’s clear that nothing is what it seems. Which is why I can’t stop wondering about the fate of poor Steve Bing.

Published on June 26, 2020 11:13

June 23, 2020

May the Space Force Be With You

Hollywood makes for strange bedfellows. And quarantines, I’ve learned, can make for some strange TV watching. Up until now I had thought that Steve Carell could do no wrong. Over the years I’ve cheered for his many and varied screen performances: as a sweet, shy doofus in The Forty-Year-Old Virgin (2005), as a gay Proust scholar with a suicidal streak in Little Miss Sunshine (2006), as a good-hearted supervillain boasting an impenetrable accent in the animated Despicable Me (2010). Mostly he’s been known for comedy, but his biographical role as murderous wrestling enthusiast John E. du Pont in Foxcatcher (2014) nabbed him an Oscar nomination.

He’s a writer too, responsible for the script of The Forty-Year-Old Virgin. And he’s both written and directed episodes of The Office, the long-running TV sitcom (2005-2013) in which he starred as Michael Scott, the world’s most well-intentioned but aggravating boss. (I’m partial to the episodes, like “Diversity Day,” in which he clumsily tries to promote interracial good will while infuriating absolutely everyone on his staff.)

So what’s he up to now? Well, on May 29 of this year, when we were all deep into social distancing mode, Carell and writer-producer Greg Daniels (who worked with him on The Office) introduced a ten-part new Netflix comedy series, Space Force. As the title suggests, the series is intended as a satirical look at the current administration’s actual plan for a new branch of the U.S. military, intended to focus on the conquest of outer space. There’s some contemporary resonance to the show: it establishes an unnamed POTUS who likes to send out emphatic Tweets and whose proposed slogan for the new space exploration effort, “Boots on the Moon,” is a variation on his original catchphrase: “Boobs on the Moon.”

My quarantine partner is an aerospace engineer and I too have a certain interest in space exploration, so this was something we didn’t want to miss. When the Space Force moon rocket lifted up, and when the command module gracefully settled on the lunar surface, Bernie was impressed at the details that were portrayed correctly. Needless to say, the show’s satirical slant also required some ludicrous exaggerations, like a launch that was moved up by four years to thwart a competing Chinese mission, necessitating a motley crew of untrained welders and electricians to staff a lunar science lab. And, as the head of the team on the ground, Carell projects the sort of oblivious geniality that marked his Michael Scott. Here he’s a four-star general, not the boss of the Scranton, PA branch of Dunder Mifflin Paper Company, but this new character is equally clueless.

For me the show’s top asset is John Malkovich, as Space Force’s chief scientist, a rather effete hyper-intellectual who’s a good counterweight to Carell’s bluff General Mark Naird. Also along for the ride is Lisa Kudrow as Mark’s wife. For reasons that are never explained, Kudrow’s Maggie has spent most of the season’s 10 episodes serving a forty-year prison sentence. (If there’s a joke here, it escapes me completely.) As for Carell’s role, no one seems to have decided whether he’s a comic buffoon or a sensitive guy missing his wife and struggling with his angry teen-aged daughter. There’s a good gag or two: the lead astronaut, an ambitious young African-American woman, agonizes over to what to say when she makes history by stepping onto the lunar service. She decides on a history-evoking phrase, “It’s good to be back on the moon,” but muffs it, saying instead, “It’s good to be Black on the moon.” Funny, but not worth ten episodes.

Published on June 23, 2020 14:09

June 19, 2020

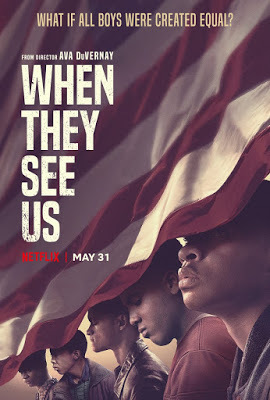

Juneteenth 2020: “When They See Us”.

Juneteenth seems a good day to muse about how far Americans have come in the struggle for Black liberation, and how very far we still have to go. When I was in school, this day commemorating the end of slavery across the U.S.A. was never once mentioned. We all understood that slavery had ended, once and for all, in 1865. It took a while, until the rise of the Civil Rights Movement, for us to grasp that African-Americans, though technically free, were far from equal in the eyes of the law.

Flash forward to 2020. In the wake of the murder of George Lloyd by a member of the Minneapolis Police Department, we’re all taking stock, yet again, of the American response to its Black citizenry. The last few weeks have seen some forward progress, everything from peaceful protests by people of all colors to the news that Aunt Jemima – the benignly beaming Mammy figure on the box of pancake mix – is going off to that Great Plantation in the Sky. But, of course, injustices continue. More harsh rhetoric, more cold-blooded killings by cops who should certainly know better.

.Given what’s going on, this seemed an apt time to catch up with a TV mini-series from 2019, Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us. This four-part drama explores the case of a jogger who was brutally raped and left for dead in New York’s Central Park in 1989. I remember the headlines at the time: the horror I felt at the notion that a group of African American teenagers, “wilding” in the park on a warm April evening, could so viciously attack a defenseless white female. The NYPD quickly swooped in and made a number of arrests. After the trials and convictions, I was glad to think of the gang who had become known as the Central Park Five as safely beyond bars for a long time to come.

Only problem: there was absolutely no forensic evidence linking the five young men (one of them barely 14) to the attack on the jogger. Yes, they had confessed to a multitude of crimes, but only after long hours of intense questioning, with their parents and attorneys nowhere in sight. DuVernay’s drama is at perhaps its most infuriating when we see exhausted boys, desperate to go home, being manipulated by police into naming one another as accomplices, even though most began the evening as complete strangers.

DuVernay’s drama, produced by such showbiz luminaries as Robert DeNiro, Oprah Winfrey, and screenwriter Robin Swicord, focuses on the five young men both before their conviction and after their release. It’s painful to see the extent to which they (and their families) are traumatized long after their release by the injustice they’ve suffered. Their stories are not identical, and DuVernay and her team do a superb job of intecutting their varied experiences into a powerful mosaic. For instance, when Raymond Santana is released from the youth authority after serving his six-year sentence, he comes home to an overcrowded apartment where his father has a hostile new wife and a toddler. But the most gripping footage involves the oldest of the boys, Korey Wise (played by Emmy-winner Jharrel Jerome) who for fourteen years suffered through the horrors of the New York prison system.

Some of the details seen on-screen have been disputed. Lead prosecutor Linda Fairstein, played by a coldly self-righteous Felicity Huffman, has cited factual errors and sued for defamation. But the abuses of young Black men by the police and prison systems are too glaring to dismiss. I will not soon forget what I have seen.

Published on June 19, 2020 14:40

June 16, 2020

What’s Goin’ On: The Many-Hatted Saga of “Da 5 Bloods”

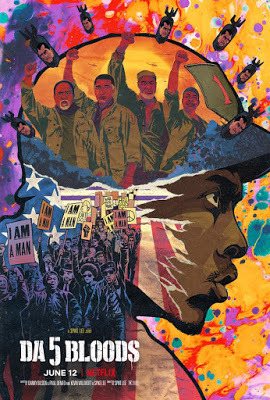

I don’t know how Spike Lee does it. Just when our national concern about social justice has reached a boiling point, he comes out with a film that addresses the very issues that make this moment so fraught. Lee knows his American history, both the widely shared events and the more hidden ones. He knows about Dr. King and Malcolm X. And he knows about Hanoi Hannah cajoling Black soldiers to reject the patriotic rhetoric that promotes the official American view of the Vietnam War. His new film, Da 5 Bloods, opens with a clip of Muhammad Ali noting that no Viet Cong ever called him nigger.

Lee has over 90 directing credits, and I can’t pretend that this is his very best work. Part of what makes his career so memorable is that, while devoting himself to chronicling the Black American experience, he has tried out so many approaches. He’s shot distinguished documentaries (Four Little Girls) and biopics (Malcolm X). He’s focused on Black music (Mo’ Betta Blues), Black religion (Red Hook Summer), and Black contributions to sports. (He Got Game). I love the sexy humor in his comic take on the streets and the bedrooms of Brooklyn, She’s Gotta Have It. And I doubt there’s a more powerful look at the rage in our streets than 1989’s Do the Right Thing.

Lee can be long-winded, with a tendency to go off in all directions. Two items in the Lee canon I most admire, 2006’s Inside Man and 2018’s BlacKkKlansman, are disciplined police thrillers that pack a wallop because they’re tightly written and edited. They’re hardly without meaning, but they never wander off from the subject at hand. By contrast, Da 5 Bloods is Homeric in its scope, covering a multitude of issues. This story of a squad of Black grunts returning to Vietnam fifty years later to find the remains of their fallen leader is at the same time a sentimental journey, an adventure saga, and a deeply poignant father/son tale. The film is also a history lesson, bookended as it is by footage of fallen Black leaders as well as shots of people of color bearing the burdens of a questionable war.. One chief plot strand, focusing on the challenges posed by human greed, is deeply reminiscent of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. (We can’t miss it, because Lee makes a joke reference to that classic’s most famous line.) In all, Da 5 Bloods is a mishmash of styles and subjects: it’s a bit formless, but never less than fascinating.

What’s special about Da 5 Bloods, apart from its timeliness and its ambitions? The breathtaking beauty of its landscape scenes owes much to the cinematography of a new Lee collaborator, Newton Thomas Sigel. (Among his previous films is Drive, which turned L.A. into a place of seedy wonder.) There’s also, unusual for a Lee film, a big orchestral score by longtime collaborator Terence Blanchard, which co-exists with a powerful rendition of Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Goin’ On.” And then there are the performers, led by Delroy Lindo, a frequent Lee supporting player who shines here in the central role.

Lindo’s character, Paul, shows more than any of the others how deeply warfare can etch itself into the human psyche. Vietnam is a battle he can never get past. Pointedly, Paul is a guy wearing a “Make America Great Again” red cap. Lee publicly loathes the president he calls “Agent Orange,” and by making a PTSD-riddled Black man a Trump supporter he makes sure we all know what’s goin’ on in his own mind.

Published on June 16, 2020 10:54

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers