Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 51

December 1, 2020

At the Core of the Big Apple: The Taking (and Retaking) of Pelham 123

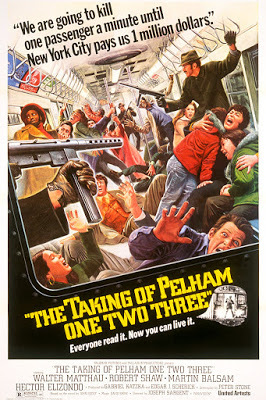

Back when I used to travel to Manhattan for business and pleasure, I often jumped on the Lexington line, heading downtown. You can see all sorts of sights on New York subways, but happily I never encountered a quartet of desperate men, disguised with hats and fake mustaches, commandeering a train car and threatening to kill passengers, one by one, if their outrageous financial demands aren’t met. That’s central to The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, a superior thriller released in 1974.

Back when I used to travel to Manhattan for business and pleasure, I often jumped on the Lexington line, heading downtown. You can see all sorts of sights on New York subways, but happily I never encountered a quartet of desperate men, disguised with hats and fake mustaches, commandeering a train car and threatening to kill passengers, one by one, if their outrageous financial demands aren’t met. That’s central to The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, a superior thriller released in 1974. I became intrigued when I read a comment by actress Cynthia Nixon, who called this “my absolute favorite movie of all time. When it comes to movies about New York City, this one blows the competition out of the water.” Given how many great NYC movies have been made over the years, Pelham had to overcome some mighty stiff competition to be at the top of Nixon’s list. Now that I’ve seen it, I understand where Nixon, a native New Yorker, is coming from. The film presents a vibrant cross-section of New York life: its characters reflect a range of ethnicities and social strata, but they all share a cranky obstinacy that makes them truly seem to be at the core of the Big Apple.

Perhaps the crankiest and most obstinate is Walter Matthau, as the head of New York Transit’s police division. It’s his job to figure out what’s going on with the southbound train called Pelham One Two Three, but his life is made no easier by the visiting Japanese dignitaries whose knowledge of English only seems limited, nor by the co-worker at headquarters who questions his every move. Eventually the city’s inept mayor and his oily chief of staff become part of the situation too, as do scores of irked commuters. But of course they’re all essentially being held hostage by the greedy, lethal, and (yes) obstinate hijackers, led by Robert Shaw. Also part of the plot is Martin Balsam, who—after some serious mayhem—features along with Matthau in one of the greatest final scenes ever.

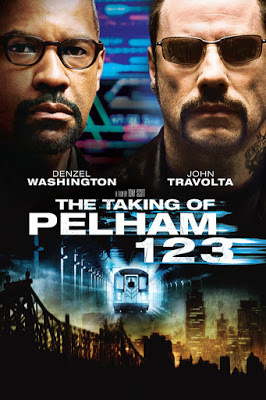

When you’ve got a movie this good, why bother to remake it? Funny you should ask. In 2009, Tony Scott decided to work his action-film magic on the property, slightly retitling it The Taking of Pelham 123. In Scott’s hands the movie has become twice as hectic, twice as violent, and at least four times as bloody, making room for lots of car crashes and other adrenaline-pumping moments. And the original ensemble piece (directed by Joseph Sargent) has somehow evolved into a star vehicle for two of Hollywood’s biggest names. John Travolta plays the twitchy leader of the bad guys, a man not just greedy but totally screwed up, motivated by a kind of weird Catholic death wish. And instead of average-schmo Walter Matthau, the head of the good guy team is now Denzel Washington, who’s not just a subway dispatcher but also a man who’s been demoted into this job because of an ethical lapse of which he may or may not be guilty. Moreover, he’s a former motorman himself, so at a certain point he ends up being summoned to take over the controls of the hijacked train car. Which puts him face to face with Travolta in the kind of movie-star showdown we could have anticipated from the start, with Denzel looking for redemption and Travolta wanting . . . well, what the heck does he really want, anyway?

A side note: the $1 million sought by the hijackers in 1974 has become $10 million in 2009. You can always count on inflation.

November 27, 2020

Thankful for “Cabin in the Sky”

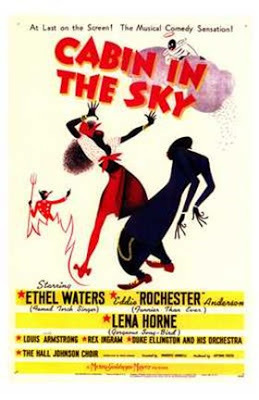

Thanksgiving is a good time for nostalgia. This year I find myself nostalgic about my late parents, whose tastes in movies (and so much else) undoubtedly shaped mine. They loved musicals, and one of their very favorite, released well before I was born, has become special to me as well. I’ve seen it countless times on TV’s late-late show, and some of its best gags (like a young demon bragging about his prowess as an evil-doer by proudly announcing, “I invented flies”) were catchphrases in my family for years.

Cabin in the Sky (1943) is a fantasy, based on a popular Broadway show in the same vein as Green Pastures, which means it boasts an all-Black cast, drawn from the ranks of the era’s most popular entertainers. The central female role, Petunia Jackson, is played by the great Ethel Waters, who similarly graced the stage version. Also featured are many of Hollywood’s favorite performers: Eddie “Rochester” Anderson as Petunia’s erring husband; Lena Horne as a devilish femme fatale; Louis Armstrong in a comic role, Duke Ellington’s band tooting away in a big nightclub scene. The songs are instant classics: “Taking a Chance on Love,” “They Say That Happiness is Just a Thing Called Joe.” The film is directed with a light and loving touch by Vincente Minnelli, at the very start of his legendary film career. (The word is that he accepted this directing assignment when more experienced white directors wouldn’t touch it.)

So what’s it about? We start in a cozy all-Black community that’s full of pious folk (a rollicking gossip hymn, “Little Black Sheep,” kicks off the film) but also some serious temptations like crap games. Petunia is saintly, but her beloved husband, Little Joe, can’t stay away from the dice. We segue to the realm of Lucifer Jr. and his demons, who are always trying to stir up trouble among earthly sinners. They tempt Little Joe with a winning lottery ticket, then send the gorgeous Georgia Brown (Lena Horne) to seal the deal. The climax, at Jim Henry’s jazz joint, seems to promise eternal damnation for several of the characters, but (surprise!) goodness wins out in the end.

There was a time when Cabin in the Sky was chased out of Southern movie houses because many white patrons were offended that so-called “sable” performers were onscreen playing something other than maids and shoeshine boys. Today, it’s easy to see how the film might offend African-Americans who consider its portrayal of Black life condescending. I put the question to my friend Clifford Mason, the playwright and theatre historian who takes seriously indeed the portrayal of Blacks on movie screens. As always, he was candid, speaking about this show as what he calls “race neutral,” this being “the popular method by which America allows Black Americans to participate in the cultural life of the country through the clever method of NOT talking about race.” He insists, with obvious sarcasm, that Cabin in the Sky is “just a nice, pleasant entertainment with nice pleasant neegrows doing what America loves to see them do: sing and dance.” In pretty much the same category, Cliff puts everything from Porgy and Bess to The Equalizer to Madea, projects in which Blackness is decorative rather than something to be seriously explored.

I can’t really argue. (I suspect that arguing with Cliff Mason would put me at a grave disadvantage.) Still, for my money Cabin in the Sky is a film in which good performers play good (and deliciously bad) people, and no one can convince me not to love it.

November 24, 2020

From Buckingham Palace to Schitt’s Creek

Call me quirky . . . I’ve been watching season four of The Crown, the starry Netflix series that delves into the public and private lives of Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II and her family. Once I’m done with each episode, I’ve been flipping to the amiable Canadian Schitt’s Creek, which swept up all the sitcom prizes at the recent Emmy celebration. The two series have not much in common, you say? True enough: one is a serious take on recent royal history, and the other is a comedic look at some fish-out-of-water Hollywood types who—having lost all their money—are forced to settle in a humble little burg full of outlandish characters. Different, right? And yet. . .

Call me quirky . . . I’ve been watching season four of The Crown, the starry Netflix series that delves into the public and private lives of Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II and her family. Once I’m done with each episode, I’ve been flipping to the amiable Canadian Schitt’s Creek, which swept up all the sitcom prizes at the recent Emmy celebration. The two series have not much in common, you say? True enough: one is a serious take on recent royal history, and the other is a comedic look at some fish-out-of-water Hollywood types who—having lost all their money—are forced to settle in a humble little burg full of outlandish characters. Different, right? And yet. . . What The Crown teaches us about British royals is that they value the institution of monarchy above all. Love and family feelings are constantly being sacrificed to what’s seen as the good of the nation. This is particularly true in season four in which the Prince of Wales, deeply in love with the married Camilla Parker Bowles, is inexorably led into a marriage with the very young, very naive Diana Spencer. Still, the Windsors are none of them heartless, and they do feel concern about the personal happiness of family members. Moreover, no matter how much they disagree on matters great and small, they still feel a strong bond of kinship. This really shines forth in the “Fairytale” episode, in which both Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and (separately) Diana try to negotiate the tight family circle that gathers at Scotland’s Balmoral Castle to stalk elk and play silly parlor games. Whatever these royal folks think of one another, they’re kin, and always will be. And outsiders are not exactly welcome.

The newly impoverished members of the Rose family, trying to carve out their own niche in Schitt’s Creek, are hardly royals, whatever they may think of themselves. But like the British royal family, these former-zillionaires-in-exile are usually oblivious to the wants and needs of the downhome folks around them. An air of condescension comes to them naturally, particularly in the case of family matriarch Moira Rose (Catherine O’Hara), a faded soap opera star still convinced of her own grandeur. For me Moira bears comparison to the hyper-snooty Princess Margaret (Helena Bonham Carter), in that she dislikes pretty much everything in her new home. By contrast, Moira’s husband Johnny (Eugene Levy, he of the highly expressive eyebrows) reminds me of the Queen herself. Like Elizabeth, he’s the glue that holds the family together, trying desperately to turn chaos into order and reassure the others of his love.

One of my favorite recent Crownepisodes is “Fagan,” covering the real-life episode in which a troubled man broke into the Queen’s Buckingham Palace bedchamber for a heart-to-heart chat about the state of the nation. We don’t know what was actually said, but writer Peter Morgan has given Olivia Colman, as Elizabeth, a marvelous degree of composure as she contends, from her bed, with the late-night intrusion of unemployed house painter Michael Fagan, who uses her bathroom and asks for a cigarette. (“Filthy habit,” she mutters.) The episode is played off against Thatcher sending British troops off to war in the Falkland Islands. But I can imagine a similarly weird intrusion occurring on Schitt’s Creek, with some local Canadian derelict breaking into the shabby motel room that’s become home to the Rose family. Moira, I’m certain, would succumb to hysteria. Offspring David and Alexis would fight over who gets to sleep with the newcomer. And poor Johnny would just try to keep the peace.

November 20, 2020

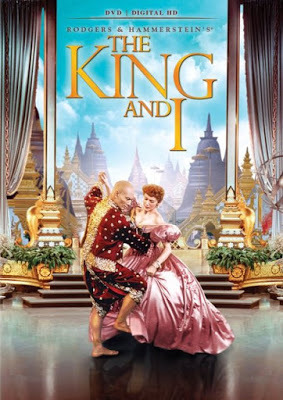

Banned in Bangkok: Thai-ing One On at the Movies

Thailand had always seemed to me a nice, quiet, faraway place. But no more. American newspapers are reporting on massive street protests against the ruling military junta and the monarchy it props up. When, decades ago, I stayed for a week with a Bangkok family, everyone seemed deeply religious and deeply in love with their king and queen. The top royal, King Bhumibol Adulyadej, was a cultivated man who loved photography and jazz, and had a passion for playing the saxophone. (I don’t hold that against him). He and his elegant queen, Sirikit, seemed to live a harmonious life, and before he died in 2016 at age 88 he was honored as the world’s longest reigning head of state.

Today, though, things are a wee bit different, with King Blumibol’s only son (age 68) sitting on the throne. He sits on it, that is, when he isn’t spending the bulk of his days at his palatial home in Bavaria. Known as a playboy, he’s divorced three wives, and his fourth stays in the background whenever the glamorous recently-named “royal noble consort” is photographed oozing coy sex appeal. It’s something of a throwback to the Siam we encountered on movie screens, in which a silk-clad despot lounged around the palace with his harem of concubines.

The 1870 memoirs of Anna Leonowens, who described her stint as the teacher of the Siamese king’s many offspring, became the basis for a best-selling 1944 novel, Anna and the King of Siam. Not many moviegoers today remember there was a non-musical film version of this novel, starring Irene Dunne as the sensible Englishwoman, Rex Harrison (!) as the king, and Linda Darnell, who often projected exoticism in her film roles, as the tragic Tuptim. Released in 1946, it appealed to audiences primed to explore far-off cultures they could regard as charming. But this black-and-white movie paled when compared to the lush Cinemascope version of The King and I, with its rich Rodgers and Hammerstein score. The latter film won 5 Oscars and was nominated for 4 more, including Best Pictures. There was a wonderful chemistry between the leads, Deborah Kerr (who didn’t quite admit in 1956 that her soprano voice was dubbed by Marni Nixon) and Yul Brynner, who walked off with an Oscar to go with his Tony awards for his indelible portrayal of the king. No one in the cast, as far as I know, was actually Thai, though Brynner’s Slavic looks and shaved head made him seem suitably foreign. Curiously, the role of Tuptim, the delicate Burmese woman gifted to the king by a foreign leader seeking to impress, was filled by none other than the very Puerto Rican Rita Moreno, who years later was finally able to return to her own roots in West Side Story.

Anyone who loves The King and I , as I do, remembers “The Small House of Uncle Thomas,” the bravura Jerome Robbins dance number that freely adapts Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, as seen through the eyes of a Southeast Asian concubine. It seems Tuptim, who has been introduced to the book by Mrs. Anna, stages it (using traditional Thai music and dance styling) to quietly comment on her own situation as a slave. The number has covert social resonance as well as charm, but today’s self-righteous audiences might well accuse it of cultural appropriation. Ah, well. It’s not easy to portray a foreign culture fairly and with respect.

When I visited Thailand, The King and I was considered insulting to the Thai royalty. Yes, both film and soundtrack album were banned in Bangkok.

November 17, 2020

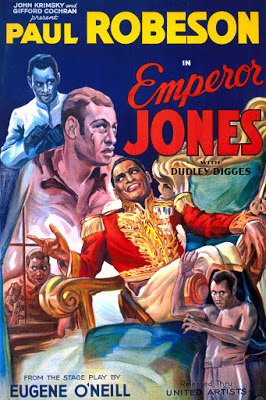

The Emperor Robeson: Clifford Mason Tells It Like It Was

“I’m the only man in the world big enough to get me.” That may sound like the ravings of a contemporary megalomaniac politician certain that no mortal can remove him from his pedestal. But the line goes back to 1920, and Eugene O’Neill’s expressionistic drama, The Emperor Jones. It’s the story of Brutus Jones, a cocky African-American Pullman porter who kills a crony in a dice game and is sentenced to hard labor on a chain gang. Escaping out to sea, he finds himself on a Caribbean island, where the credulous Black natives accept him as their divinely anointed leader. Yet there’s a snake in this paradise and it involves the workings of Jones’ own mind. When his subjects begin to turn on him, he flees into the jungle. The natives have been warned that only a silver bullet can kill him . . . but the rising cadence of their tom-toms gradually drives him mad.

It’s a bravura role for an actor, and a landmark play for the American theatre, which until that point had shied away from using Black actors in anything but comic performances. For the most part, specifically Black dramatic roles (like those in the perennial Uncle Tom’s Cabin) were played well into the 20th century by white actors with burnt-cork makeup. Many tastemakers were convinced that no African American could ever get far enough away from his jungle roots to properly intone the divine words of Shakespeare, including the title role of Othello.

I learned about much of this while reading a fascinating new book by playwright Clifford Mason. It’s titled Macbeth in Harlem; Black Theater in America from the Beginning to Raisin in the Sun. I first met Cliff online after stumbling onto a diatribe he’d published in the New York Times in 1967. It bravely took on America’s most popular Hollywood actor of that era, under the snarky headline, “Who Does White America Love Sidney Poitier So?” Cliff has the courage of his convictions, and he’s funny, to boot. Though I’ve yet to see any of his thirty-three plays, I admire him as a critic and theatre historian, especially after reading this well-researched (though deeply idiosyncratic and sometimes cranky) study.

In Cliff’s book I read about thespian Ira Aldridge (1807-1867), who had to leave America. to star on European stages in classical roles. And I read about Bert Williams (1874-1922), a gifted song-and-dance man forced to darken his light skin with burnt cork in order to fulfill the stereotype of the “colored” entertainer. Then there’s the controversial staging of an all-Black Caribbean-style Macbeth in Harlem, under the direction of the young Orson Welles, through the support of the Depression-era Federal Theatre Project. But the figure who lingers in my mind is Paul Robeson (1898-1976), the multi-talented singer/actor/scholar/athlete who briefly set the theatre world alight before running afoul of the U.S. government during the McCarthy era. Cliff’s book sent me to Robeson’s performance in Hollywood’s 1933 screen version of The Emperor Jones. Despite the creakiness of the filming, it’s a powerhouse performance, one of Robeson’s few major screen roles before he soured on Hollywood’s brand of social conservatism.

We can’t forget Robeson’s glorious basso voice. The screen version of The Emperor Jones enables him to sing church hymns and chain gang songs, while also impressively delivering the extended monologue that ends the film. Another showcase for his musical talent is Showboat: he sings “Old Man River” in the 1936 musical in which Helen Morgan (a white actress) plays the inevitable tragic mulatto role. But Hollywood, alas, never made full use of this magnificent man.

November 13, 2020

Staring at Squares: The Queen’s Gambit

I’m no chess player. Years ago my father tried to teach me the game, but quickly gave up. For me it was too solemn, too complicated, too slow. So why was I mesmerized by a television drama in which the most passionate moments take place over a chessboard?

I’m no chess player. Years ago my father tried to teach me the game, but quickly gave up. For me it was too solemn, too complicated, too slow. So why was I mesmerized by a television drama in which the most passionate moments take place over a chessboard? The Queen’s Gambit is a seven-part Netflix miniseries about a young girl who grows up to be an international chess master. Sounds like a snoozer, right? But not if you think of Beth Harmon’s story as Cinderellawith a modern twist (and a dash of Through the Looking-Glass thrown in for good measure). Before Beth evolves into the belle of the ball—or rather the belle of the chess tournament—she’s a waif in the Grimm-est of fairytales. Her birth mother is crazy and suicidal. Her father seems non-existent. After surviving a catastrophic car crash, she’s sent off to live in a spooky old orphanage where the religious instruction is heavy-handed and little girls are dosed with tranquilizers at bedtime to keep them under wraps. And down in the basement there’s . . . . no, not a monster but a gruff old janitor who loves chess. His lair becomes little Beth’s salvation.

When a teenaged Beth is adopted into the cozy home of a middle-aged Kentucky couple, things seem to be looking up. But more heartbreak awaits. Her new father doesn’t want her, and doesn’t want to be married. Her new mother is a neurotic soul who encourages Beth’s chess talents but also passes on to Beth her own dependence on pills and alcohol. The kids at school don’t know what to make of her, and more and more chess comes to seem both her emotional and her economic salvation.

Chess tournaments also introduce her to a host of young men, many of them infatuated by her good looks and aggressive, intuitive style of play. Love seems to await her, along with fame and fortune (she earns major cash prices and graces the cover of major magazines), but her own inner darkness usually gets in the way of successful relationships. So she settles for sex, along with her other vices.

The series builds to a climactic tournament in Soviet-era Moscow, a sort of paradise for chess players, where fans gather in the street outside the palatial chess hall to breathlessly await the play-by-play. Will Beth slay the Soviet dragon? Or will she succumb to the dangers and temptations that have dogged her along the way? Since this is a modern fairytale, we suspect a happy ending, but of course one that springs some sort of unexpected surprise. And The Queen’s Gambit (the name of a classic chess move) does not disappoint.

Anya Taylor-Joy, an actress new to me, is a revelation as Beth, who grows from gawky wallflower to stunning (though deeply troubled) young woman of the world. Bill Camp as that crusty old janitor and actress/director Marielle Heller as the adoptive mom head a strong cast. But the real star of the series may be its inventive staging and cinematography, which manage to imbue numerous games of chess with real drama, even for those of us who can’t tell a rook from a bishop. Chess players revere their calling, and this series has been praised for its accuracy. I’ve read that some of the high-level games played in the series were borrowed from the historic record, though of course the glacial pace of a real chess match has been speeded up for the benefit of the TV audience. Hmmm, maybe this is a good sport for quarantine.

November 10, 2020

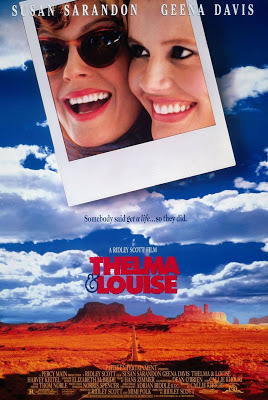

Waiting for Kamala: the Journey of Thelma and Louise

Over the weekend, as our nation confronted the prospect of its first female vice-president, I went back to a movie that made a major splash almost 30 years ago, Thelma & Louise. This film directed by Ridley Scott from an Oscar-winning script by newcomer Callie Khouri, generated box-office bucks and critical acclaim for taking a mostly-male genre, the buddy road-trip flick, and turning it into a powerful exploration of a woman’s place in the American landscape.

Thelma & Louise starts out, as so many road-trip movies do, with two very different characters getting ready to go on a journey. The mood is light-hearted, even comedic, as sassy Louise (Susan Sarandon), a waitress in an Arkansas café, phones her ditsy friend Thelma to nudge her into action. Their destination is a fishing cabin, but Thelma (Geena Davis), the wife of a local car dealer, seems so daunted by the prospect of heading out of town that she can’t quite bring herself to alert her spouse that she’ll be gone for two nights. Thelma, it appears, is so much under the thumb of the domineering Darryl that she has a hard time thinking for herself. Which is why she packs pretty much everything she owns.

Away from Darryl, Thelma gives herself over to impulse. She insists to Louise that they stop at a Texas-style honkytonk bar, where she drinks too much and then cozies up to a flirtatious local named Harlan. It’s all in good fun—until it isn’t. Out in the parking lot, Harlan is pawing at her clothing, bent on sexual satisfaction by any means necessary. That’s when Louise appears, brandishing the handgun that Thelma had casually brought along.

What happens from that moment onward reflects the inevitable fate of two women caught in a man’s world. With the law on their trail, they run up against such antagonists as a sexy hitchhiker (Brad Pitt, in his first big role) who steals their money and a horny trucker who’s itching for trouble. Not to mention Thelma’s husband back home, who clearly regards her plight as a mere inconvenience. Though the film has been accused of having an anti-male bias, a few generous-spirited men do emerge, including Harvey Keitel’s sympathetic police detective and Louise’s supportive boyfriend. Still, the point is that the women in this world, lacking much in the way of education or earning power, exist to be victimized. It is only when an act of violence releases them from normal social expectations that Louise and Thelma feel free to blossom—for a while.

Seeing the clingy, confused Thelma come into her own is, in its way, a beautiful thing. As for Louise, the natural-born leader of the pair, she’s fighting off something that is never clearly defined. We know only that she left her Texas hometown after a traumatic incident she will not discuss. Her role in perpetrating the violence that fuels the rest of the film seems to have evolved, we realize, out of a long-delayed reaction to a moment that has made her suspicious of men forever.

Thelma & Louise owes something to 1967’s Bonnie and Clyde, the lovers-on-the-lam classic that made bank robbery seem exhilarating, while also exploring the implications of the socio-economic divide between rich and poor. It also, in its end-of-the-road climax, perhaps contains a tiny echo of 1969’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. But most of all this is a film that focuses on the fraught power dynamic between men and women.

Kamala Harris—well-educated, well-placed, and capable—is a much more encouraging example of how women’s power can evolve.

November 6, 2020

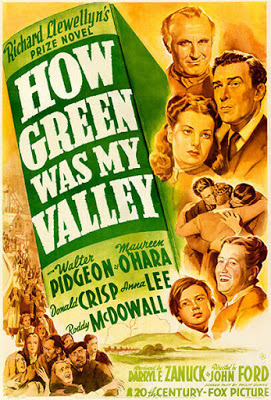

How Long Ago and Far Away Was My Valley

When the present is filled with anxiety, movies can be helpful in wafting us to long ago and far away. That’s why I spent part of election day in Victorian-era Wales, watching John Ford’s 1941 screen adaptation of Richard Llewellyn’s popular novel, How Green Was My Valley. I’d read the novel in high school, falling in love with this saga of a family of Welsh coal miners. Ford’s film was so respected by Hollywood that it won the Best Picture Oscar against stiff competition, including Citizen Kane. It also nabbed four additional Oscars, including Best Director, nods for black-and-white cinematography and art direction, and a well-deserved Supporting Actor statuette for Donald Crisp, as the Morgan family’s indomitable patriarch. Five additional nominations included the categories of Best Supporting Actress (for feisty mother-figure Sara Allgood) and Best Musical Score. The Welsh love of choral singing was beautifully highlighted in the film by Alfred Newman’s work.

The central figure in How Green is My Valley is Huw Morgan, vividly played on screen by Roddy MacDowell, just starting out on his long cinematic career. It’s a memory piece, beginning with now-grown-up Huw, in voiceover, leaving the valley and its family connections behind. The Morgans (with Huw as the youngest of 6 sons) have worked for generations in the local colliery, or coal mine. Over the years the soot from the mine has gotten deep into their skin, and into their souls. With their father they’ve gone down into the pit daily, collecting their wages, politely tipping their caps to the clerk, and returning home (singing all the while) to deposit their earnings into their mother’s apron. From their parents they’ve learned the dignity of labor, polite manners, religious faith, and deep family feelings. But as economic conditions worsen, cracks appear in the family’s unified front. Several of the brothers strongly favor the formation of a labor union, outraging their tradition-minded father. Mine disasters are frequent, claiming many local lives. A subplot focuses on the story of the family’s spirited daughter, Angharad (Maureen O’Hara), who loves the local minister but is persuaded to marry the wealthy, snooty mine owner’s son.

I’ve recently seen The Quiet Man, also featuring O’Hara, and they make an interesting comparison. The Quiet Man, set in Ford’s beloved Irish countryside, can be seen as the flip-side of How Green is My Valley. Both revel in portrayals of small-town life, among people who dwell close to the soil, and both boast colorful characters galore. But The Quiet Man is a raucous comedy, while How Green is My Valley (for all its lively comic moments) is filled with heartbreak. The latter film is also a reminder of how hard it is to adapt a fat historic novel to the screen. So many fascinating situations are set up and then quickly dropped, like scenes in which Huw, starting school among better-dressed children in the next valley, is physically brutalized by both kids and their teacher for his coal-miner roots. The teacher gets his hilarious but vicious comeuppance at the hands of a local boxing champ, and then almost immediately Huw is graduating, earning honors and a scholarship, without any sense of how this came to pass. Angharad moves with her husband to Cape Town, of all places, and then suddenly returns. There’s just not room in any movie for all the connective tissue that a good novel can supply.

One amusing note: the plan was to film in Wales, but World War II changed that. And so the film’s charming and authentic-looking Welsh village was built in the hills of Malibu, California. Who knew?

November 3, 2020

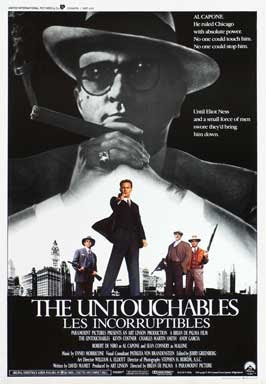

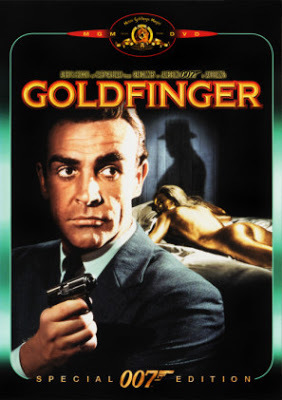

The Untouchable (and oh so touchable!) Sean Connery

Who would have thought that a husky working-class kid from Edinburgh—one who cadged jobs as a milkman, an artist’s model, and a coffin polisher—would one day find worldwide fame as a symbol of suave British masculinity? That was the through-line for the late, great Sean Connery, whom we lost this past week at the age of 90. His first professional stage job, as a chorus boy in the London company of South Pacific, didn’t seem to promise much. But once he was cast (to the chagrin of author Ian Fleming) as the screen’s first James Bond, he shot to fame for playing the brilliant, sexy spy in 1962’s Dr. No and six other Bond films. Fleming had been hoping for the witty and charming David Niven to portray the character he’d created, but Connery’s well-disciplined machismo in the role completely won him over.

Connery could have portrayed Bond, James Bond, with enduring success for decades to come, but it’s a mark of the man that he sought to move beyond the role that had made him an international sex symbol. Still, whether he was performing for Alfred Hitchcock (in Marnie), Michael Bay (The Rock) or Steven Spielberg (as Indy’s professor-father in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade), he generally stuck close to action roles, in which he effectively played leaders and authority figures. One unusual detour was appearing as a middle-aged Robin Hood opposite Audrey Hepburn’s Maid Marian in Richard Lester’s Robin and Marian in 1976. But perhaps the pinnacle of his career came eleven years later with his Oscar-winning role in Brian De Palma’s (and David Mamet’s) operatic take on The Untouchables.

From my Roger Corman days, I’ve always had a certain affection for Al Capone movies. I worked on Caponewith writer Howard Browne (a onetime Windy City newsman who insisted in true hard-boiled fashion that he “loved Chicago the way you love a woman”). Our Capone was Ben Gazzara; later I helped work on the script (by my pal Michael Druxman) of Dillinger and Capone, starring Martin Sheen and F. Murray Abraham. The Untouchables features the great Robert De Niro as the Italian-American mobster, who in this version reminds me vividly of some politicians I could name. I love his silky blandishments when meeting the press (“Yes! There is violence in Chicago. But not by me, and not by anybody who works for me, and I'll tell you why, because it's bad for business.”) I also adore the tears he sheds at the opera, as well as—most especially—the glee with which he goes about keeping his flunkies in line.

In this version of the Capone story, it’s the good guys who take center stage. The leading role of treasury agent Eliot Ness is played by Kevin Costner, who looks terrific in the production’s Armani suits but otherwise remains his usual slightly bland self. His posse consists of Charles Martin Smith as a dorky but smart accountant as well as a young Andy Garcia in the role of an Italian-American aspirant to the Chicago police force. And then there’s Connery, playing a world-weary Irish-American beat cop who’s doubtless too honest for his own good. Connery is the soul of this production, as a man so bitter at the corruption he sees all around him that he’s willing to risk everything in order to save his city from itself. In a film that has bravura moments but also its share of logic glitches (not to mention an excessive amount of gore), the grizzled but heroic Connery stands out for his humor and his heart.

October 30, 2020

A Very Hugh Grant Scandal

He’s cute and cuddly, with floppy hair, baby-blue eyes, and the gobsmacked look of a lovestruck teenager. The Jeopardy question would be: Who is Hugh Grant? Actors, of course, are not identical to the roles they play. But after seeing (more than once) such charming British films as Four Weddings and a Funeral, Notting Hill, and Love, Actually, I find it hard not to associate Grant forever with his signature romantic roles.

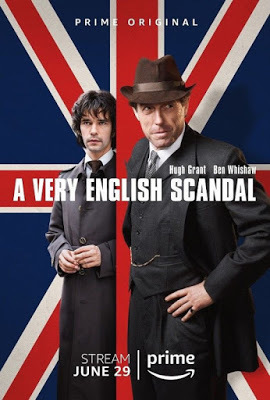

But Grant is (gulp!) sixty now, and more than ready to put those adorable personae behind him. He was ambiguous as the supportive (though philandering) husband of Meryl Streep in 2016’s Florence Foster Jenkins. And he’s moved much further into dark territory of late with such TV fare as A Very English Scandal, presented by Amazon Prime in 2018. It is a three-part enactment, directed by the always worthy Stephen Frears, of an actual political scandal that mesmerized the British press and the British public in 1976-1979.

Grant (who was a very cute, very young British prime minister in Love, Actually) here plays Jeremy Thorpe, a Member of Parliament who is moving rapidly into the leadership of the upstart Liberal Party. Charming and cocky, he deftly conceals ongoing homosexual flings (wholly illegal in England until 1967) while appearing in public as a progressive statesman with a bright future. In 1961, while visiting a country estate, Thorpe meets a naive 21-year-old stable boy named Norman Josiffe, and feels a strong attraction. When Norman shows up in London, out of work and desperate, Thorpe installs him in an apartment and seduces him into the life of a kept man. Norman (in the stunning performance of Ben Whishaw) is a chap who’s destined to cause trouble. Mentally unstable, he craves beyond anything to be loved and to have that love acknowledged. Though Thorpe was once smitten enough to write him passionate letters, he also recognizes Norman as a liability to his political future. That’s why he eventually cuts Norman loose . . . but there is hell to pay.

Norman—who now calls himself Norman Scott—tries on various post-Thorpe lifestyles, succeeding briefly as a male model and party-boy. He also, briefly, gets married . . . as does Thorpe, twice. But the always erratic Norman wants public recognition of the affair, as well as a reinstatement of his essential National Health card, which would threaten to expose the true nature of his past Thorpe connection. Stymied by Norman’s growing coziness with the tabloid press, Thorpe comes to an important conclusion. He wants Norman Scott dead.

Norman doesn’t die. In fact the real Norman Scott is alive and well, as revealed in the series’ inevitable final crawl. But far be it from me to disclose the grim outcome of Thorpe’s skullduggery, as well as the results of the trial that gripped the United Kingdom in the late 1970s. Why is this scandal so “very English”? Perhaps because it tells us a great deal about the English talent for keeping up a façade, whatever the circumstances. And it also implies many things about British class distinctions, and how these enable the upper classes to live lives of their own choosing, while also skirting social and sexual standards to which they merely pay (stiff upper)lip-service.

For me both Wishaw and Grant were revelations. I don’t know Wishaw’s work, though I’ll certainly be looking out for it in future. As for Grant, who also stars with Nicole Kidman in this year’s new series, The Undoing, who knew he’d be so good at being bad?

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers