Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 49

February 9, 2021

Christopher Plummer: Good Night, Sweet Prince

I was a devoted fan of Christopher Plummer before I ever saw his work. It seems that while growing up I was one of those artsy kids who holed up in the local library and read plays I never expected to see on stage. One that enthralled me was J.B., a 1958 verse drama by Archibald MacLeish that spins out a modern-day version of the Book of Job inside a very allegorical circus tent. A character named Nickles (read: Old Nick) plays the Satanic role, and of course he has all the best lines. I figured any actor who could do justice to this magnificent part would hold me in thrall forever. What was that name again? Ah yes, Christopher Plummer.

I never actually saw J.B. (which I suspect today might bore me to tears). I first laid eyes on Plummer in 1962 via my television set, playing the bravura role of Cyrano de Bergerac opposite Hope Lange’s Roxanne in a prestige production sponsored by the always reliable Hallmark Hall of Fame. Two years later, he was nominated for an Emmy after taking on the leading role in a televised BBC production of Hamlet, shot on location at Denmark’s actual Elsinore Castle. (The nearly three-hour event was called Hamlet at Elsinore.) By that point in his career, there was clearly no stopping Plummer, who moved with ease between stage, film, and television, starring in both classical and contemporary roles. I’m most intrigued by his work in Peter Shaffer’s The Royal Hunt of the Sun (1965). On Broadway, Plummer played Francisco Pizarro, the Spanish conqueror (and destroyer) of the Inca empire, opposite David Carradine as the mystical Peruvian lord Atahualpa. When this fascinating play about clashing cultures was transferred to the screen in 1969, Robert Shaw took the Pizarro role, while Plummer donned Atahualpa’s loincloth, beads, and feathers. (It clearly never occurred to anyone to find a genuine Latin American for the role.)

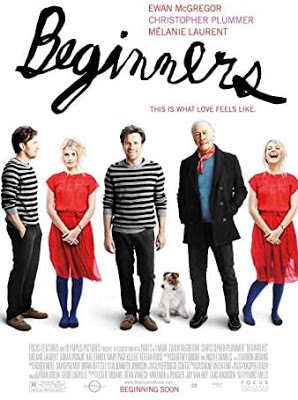

Of course every obit I’ve seen since Plummer left us February 5 at the age of 91 has mentioned his portrayal of Captain Von Trapp in the 1965 film version of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, The Sound of Music. Plummer wasn’t much of a fan of this treacly material, and neither am I. (I wouldn’t, though, go as far as he apparently did in referring to this legendary smash hit as The Sound of Mucus.) I’d rather mention the lively character roles of his later years. He received his first Oscar nomination in 2009 for portraying the great novelist Tolstoy at the end of his life in The Last Station. He didn’t win then, but took home the golden statuette in 2012 for his supporting role as an elderly widower who boggles his grown children by taking a male lover. He was then 82, and the oldest Oscar winner of all time. (He was to be nominated again in 2017 for playing J. Paul Getty in All the Money in the World.) I won’t soon forget how he anchored the delicious 2019 crime drama, Knives Out. Nor the entrancing one-man stage production in which he toured, celebrating the joys of the written word.

Plummer’s role in Beginners has an ironic parallel to an Emmy-nominated performance by another great actor who died this past week. Hal Holbrook was most famous for his vivid lifelong impersonations of Mark Twain. But back in 1972 he starred in a then-daring made-for-television drama called That Certain Summer, about a divorced father who must reveal to his young son that he’s gay. Suddenly we’ve lost both men. Ironic, no?

February 5, 2021

Dancing at the Drive-In: The Joys of Dance Camera West

Yes, I worked on this drive-in classic

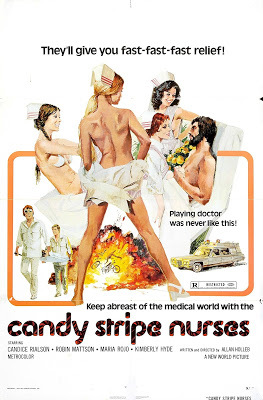

Yes, I worked on this drive-in classicWhen I worked at New World Pictures, we all knew that drive-ins were the key to our B-movie success. One of my many duties was to keep track of the distribution of films like Night Call Nurses (“It’s Always Harder at Night”) and Caged Heat. In that pre-computer age, I had to record in a ledger how many times our films had played in such outposts of American culture as the Dogwood Drive-In in Palestine, Texas and the Yazoo Drive-In in Yazoo City, Mississippi. But even then, drive-ins were going away, victims of the high price of real estate and the ongoing spread of the suburbs.

Who knew back then that one day, under pandemic conditions, a drive-in might be the only way to leave home and see a movie on a giant screen? It used to be easy, if you lived in West L.A., to watch any sort of film that interested you – art house, blockbuster, genre flick, classic – from the comfort of a multiplex theatre seat. Now, though, you need to drive a long distance to search out the few drive-in theatres in the area, including the Vineland Drive-In in the City of Industry and the seventy-year-old Mission Tiki Drive-In in Montclair, where you can watch a movie while sitting (how Southern California!) behind the wheel of your car. Other venues are trying their best to get into the act, showing movies on roof-tops and in parking lots. Which is how I came to see two nights of something called Dance Camera West, under the auspices of Santa Monica’s Broad Stage.

Dance Camera West is an organization promoting dance on cinema, by way of an annual festival of short films from all over the world. What I saw at the drive-in screening, in the parking lot of a satellite campus of Santa Monica College, was a Best of the Fest selection of 16 short pieces (eight each night). It was not, to be honest, the full drive-in experience. No popcorn for sale; no concessions shack; and -- as far as I could tell – no one was making out in the back seat of a souped-up car. We all watched quietly behind our windshields, signaling our enthusiasm at the end of each piece by honking our horns.

And what were the films like? They were a well-assorted bunch: some funny, some tragic; a few ponderously “meaningful”; most joyous in their affection for bodies in motion. Though all contained dance of some sort, the spotlight was really on the film director, whose imagination and daring showed off the dancers from new angles and in surprising contexts. Several of my very favorites (one from Portugal, one from Australia, one made in Moab, Utah) filmed the dancers in exotic outdoor settings – leaping on desert bluffs, undulating on the shore of a great sea, suspended from the walls of monolithic modern buildings. (Cameras mounted on drones allowed for an otherworldly perspective, which in the Australian film made the dancers look like giant insects surging across the landscape) A few films made a direct comment on our current safer-at-home predicament: one German-based director enlisted a handful of dancers who managed to photograph themselves all cavorting to the same tune from their individual bedrooms and kitchens. A somewhat traditional-looking Argentine film, featuring paired tango dancers gliding gracefully across the floor of a glass-walled studio, broke free of its location at the close to show one participant leaving the gathering, climbing onto a bus, and heading back home to her everyday life.

Afterwards, did these movies make me feel like dancing? Yes indeed.

February 2, 2021

Age Enhances Beauty: A Salute to Cloris Leachman and Cicely Tyson

We’ve just lost two Hollywood icons who enjoyed long showbiz careers. Both Cloris Leachman, who passed away January 27 at age 94, and Cicely Tyson, who died the following day at 96, were performing on film and television almost until the very end. It’s wonderful to see that talented, award-winning actresses are not always put out to pasture when their glamour days are behind them.

This thought, that women past a certain age can continue to have acting careers, is an encouraging one. The British have always been better than we are at appreciating their well-seasoned performers, as witness the leading roles that are still being played by such stars as Maggie Smith, Helen Mirren, and Judi Dench. I’m old enough to recall seeing Dame Judi as a sexy Titania in a long-ago TV performance of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream: I’ll never forget how she was described in the press as “toothsome.” Today, at 86, she doesn’t flaunt her sex appeal, but she still plays stellar roles and wins awards.

In the U.S., Meryl Streep (going on 72) contains to play leads, even getting the guy in last year’s The Prom. Still, we have a long tradition of shying away from the whole ageing process, especially when it applies to women. This was emphatically brought home to me last week when I watched a Hollywood classic, 1950’s All About Eve. This exhilarating backstage drama claims to be about stage actors, but its implication for the ladies of the silver screen can’t be overlooked. In All About Eve, Bette Davis (at 42) plays Margo Channing, a beloved stage actress, one for whom Broadway’s best playwright creates leading romantic parts. Though at the top of her game, Margo remains insecure—and with very good reason, because a ruthless young understudy named Eve Harrington is ready and willing to take over her roles and her place on the Great White Way. No one disputes Margo’s talent, but it’s strongly suggested that she’s hopelessly past her prime.

All About Eve may be an oldie, but—regarding ageing actresses—times have not entirely changed for the better. In 2015, a viral video captured Amy Schumer being schooled by fellow Hollywood icons Tina Fey, Julia Louis-Dreyfus, and Patricia Arquette on the danger of approaching her “last fuckable day.” Once, it’s implied, she’s no longer sexually appealing, her bright career will quickly dim.

Cloris Leachman came out of television to win a supporting actress Oscar in 1971’s melancholy The Last Picture Show. Rarely a leading lady, she played the hilarious supporting role of Frau Blücher (insert horse whinny here) in Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein, and also showed off her rambunctious side in a Roger Corman outlaw flick, Crazy Mama. I remember her most fondly as Phyllis Lindstrom, Mary Tyler Moore’s TV neighbor, who copes hilariously with an off-screen husband who’s been canoodling with Betty White’s “Happy Homemaker.”

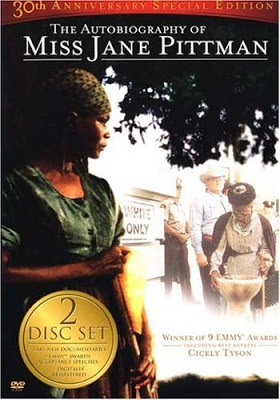

Cicely Tyson made a big impression in the Seventies as a sharecropper in Sounder (best actress Oscar nomination) and in the title role of The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (Emmy award). The two roles shaped her determination to play dignified African-American characters who advance the cause of civil rights. Thereafter she continued to rack up honors for stage and TV work. Lucky me: I saw her starring in a stage revival of The Trip to Bountiful. Her part was that of an ancient woman returning to her small-town Texas home one last time. Then nearly 90, she was charming but convincingly feeble—until she strode out for her curtain call. Then it seemed fair to call her ageless.

January 29, 2021

Saving a White Tiger (one whose bite is worse than his bark)

Many years ago, in a New Delhi zoo, I saw a white tiger. It was a beautiful and powerful animal, restlessly prowling its grim-looking cage. On that same trip to India, I also saw a cross-section of humanity I’ll never forget. I didn’t have much close contact with the very rich or the very poor, but being among educated, financially stable people like me was startling in its own way. I was treated as a welcome guest in a number of middle-class households, but could never get used to the presence of servants. Staying with one family in a comfortable but hardly luxurious flat in Bombay (now Mumbai), I was shocked to discover that the family housemaid—a pleasant woman responsible for cooking, cleaning, and childcare—slept each night just outside the apartment, on the doormat. This personal interaction with a member of the Indian underclass made me realize how naïve I’d been in my view of human dignity.

Many years ago, in a New Delhi zoo, I saw a white tiger. It was a beautiful and powerful animal, restlessly prowling its grim-looking cage. On that same trip to India, I also saw a cross-section of humanity I’ll never forget. I didn’t have much close contact with the very rich or the very poor, but being among educated, financially stable people like me was startling in its own way. I was treated as a welcome guest in a number of middle-class households, but could never get used to the presence of servants. Staying with one family in a comfortable but hardly luxurious flat in Bombay (now Mumbai), I was shocked to discover that the family housemaid—a pleasant woman responsible for cooking, cleaning, and childcare—slept each night just outside the apartment, on the doormat. This personal interaction with a member of the Indian underclass made me realize how naïve I’d been in my view of human dignity. The legend, apparently, is that a white tiger comes along only once in a generation. The tiger—rare and dazzling—becomes the spirit animal (so to speak) of the lead character in The White Tiger, a debut novel by Aravind Adiga that won the prestigious Man Booker Prize in 2008. I haven’t read the novel, but now it’s a fascinating film, passionately directed by Adiga’s longtime friend, the Iranian-American Ramin Bahrani. The movie, featuring an all-Indian cast, reveals a slice of Indian life that is both exciting to look at and deeply disturbing to experience. At its heart is the role of the servant class in today’s India.

The India of The White Tiger boasts computer technology, high-rise luxury hotels, and sophisticated call centers. Still, the lifestyle of its wealthy citizens depends on the labors of kowtowing servants who obey their masters’ every whim with a smile, tolerating insults and even physical abuse, while regarding their employers as family. Balram (Adarsh Gourav) is an eager young lad, pulled out of school at an early age because his father can’t afford the fees, who maneuvers to attach himself to a local honcho as an in-house driver. The film shows him evolving, through a series of vivid episodes, from a devoted underling to a crafty young man ready to put his own goals ahead of those of the ruling class. Particularly mesmerizing is his interaction with his boss’s younger son (Rajkummar Rao), who was schooled in America. Hip and restless, handsome young Ashok ponders his future prospects, expecting his driver to be sometimes a lackey and sometimes a confidante. Even more interesting is the son’s new wife, Pinky Madam, played by the gorgeous Priyanka Chopra Jonas, who served as one of the film’s producers as well as playing a key role. As an Indian-American raised by working-class bodega owners in Washington Heights, Pinky veers between democratic sympathy for the underdog and a bad case of social hauteur. It is she who sets off a wild chain of events that will prove fateful to all concerned.

Much of the plot of The White Tiger can be viewed as tragic, but its final scenes take us in the direction of black comedy, as Balram becomes determined to better himself, no matter what. There’s also the witty fact that the story as we see it unfold is narrated by an older Balram, who –now a successful businessman—is trying to impress the visiting Chinese premier with his entrepreneurial talents. (“America is so yesterday,” he says, insisting that the brown man and the yellow man hold the keys to the world of tomorrow. Maybe he’s right?)

January 26, 2021

All in the Family: The Levys of Schitt’s Creek

As I watch the final season of Canadian sitcom Schitt’s Creek (the best antidote I know for 10 months in quarantine), I continue to marvel at the show’s cozy sense of family solidarity. True, this is hardly Father Knows Best. The four Roses, who were forced to move from SoCal to a tiny Canadian hamlet because of disastrous financial reverses—are about as eccentric as you can imagine. Mom Moira Rose, a former soap opera queen, is an outrageous diva given to wearing fur and feathers on all occasions. Son David has sexually questionable tastes, as well as a wardrobe to die for. Daughter Alexis seems to have been horizontal with every hunk in Hollywood. Dad Johnny, a one-time video-store magnate, keeps desperately trying to hold the family together, with mixed results. Still, they love each other—and their eccentricities are rivaled by those of the local citizenry, who have perfected the Canadian art of tolerance as they take the Roses to their hearts.

If the Roses are convincing as a family, it’s partly because they partly are. Star and series co-creator Eugene Levy plays the dad, and son David is portrayed by his actual son, Dan, the co-creator who also recently won Emmys for writing and directing episodes of the series. Daughter Alexis is played by the deliciously vacuous Annie Murphy, who in real life is not actually part of the Levy bloodline. But the proprietor of the local eatery is Sarah Levy, who as Twyla is charged with whirring up fruit smoothies for her dad and brother. And the role of the family mom (who often seems more juvenile than her offspring) is filled by the unforgettable Catherine O’Hara. She and Eugene Levy are NOT actually married, but the sense they convey of the push-and-pull of married life may come from the fact that they’ve often played spouses, notably in Christopher Guest’s doggone outrageous satire, Best in Show (2000), in which she is the wife who’s been around the block a time or three and he is the husband with (literally) two left feet. They also make a big impression in Guest’s 2003 follow-up, A Mighty Wind. In this spoof of the Sixties folk music scene, set at a years-later reunion of some of the era’s biggest acts, they score as Mitch and Mickey. Formerly, according to the film, they were musical sweethearts, known for their tender “A Kiss at the End of the Rainbow” (he on guitar, she strumming an autoharp while gazing into his eyes). Now, though, he’s a spaced-out former hippie for whom she’s still quietly pining.

The comfort shown by Levy and O’Hara in playing these wacky roles goes back at least to their earliest Christopher Guest project, 1996’s Waiting for Guffman. Guest, who as an actor was part of This is Spinal Tap, tried his own hand at creating a mockumentary in Guffman, while also starring as a flighty (to put it kindly) theatre director determined to wring talent out of a quartet of Missouri locals putting on the sesquicentennial celebration of their town’s founding. He shared scripting duties with Eugene Levy, who also shows up onscreen as the local dentist (and would-be comedian). In this early Guest film, O’Hara is mated to another of Guest’s regulars, the late Fred Willard. They play travel agents who’d rather sing and dance. (Willard is the jolly one with a quip for every occasion, while O’Hara’s character quietly uses alcohol to drown him out.)

Eugene Levy helped script all these films, and it’s clear his writing (as well as his acting) talents run in the family.

January 21, 2021

When Lana Clarkson Met Phil Spector: To Know Him is NOT to Love Him

Well, music mogul Phil Spector is dead. I’m sorry, of course, for anyone who succumbs to COVID, but far be it for me to pay tribute to a madman and a murderer. Instead, I want to mark his passing by remembering his victim, Lana Clarkson. She was a B-movie actress—tall, blonde, and gorgeous—who on February 3, 2003 met Spector at Hollywood’s House of Blues, and accompanied him back to his castle-like mansion in (of all places) suburban Alhambra, California. Exactly what happened between them that night remains a mystery, but she suffered a fatal gunshot wound to the mouth, and courts did not buy Spector’s claim that her death was an “accidental suicide.”

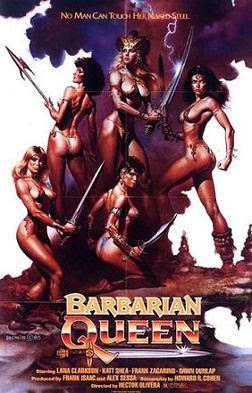

I never met Lana Clarkson, but I knew many of the people involved with making perhaps her most notable film, Barbarian Queen (1985). It was a classic Roger Corman quickie, shot in Argentina by Héctor Olivera, a courtly Argentine gentleman best known for the satiric Funny Dirty Little War, and written by a Corman regular, the late Howard R. Cohen. Corman’s minions were well versed in the selling of movies by way of eye-catching poster art, and Boris Vallejo’s poster for Barbarian Queen says it all: it shows a gaggle of young lovelies who wear little but suntans, each of them brandishing a lethal-looking sword or spear. The catchline: “No man can touch her naked steel.” (At Concorde-New Horizons, we were good at coming up with suggestive turns of phrase.)

Barbarian Queen well served the audience for which it was intended, which I think of as horny young men with money for video rentals. The irrepressible Joe Bob Briggs, a Texas-born promoter of B-movies, gave it a stellar review: "It's no Conan the Barbarian II, but it's got what it takes, namely: Forty-six breasts, including two on the male lead. Thirty-one dead bodies. Heads roll. Head spills. Three gang rapes. Women in chains. Orgy. Slave-girl sharing. One bird's-nest bra. The diabolical garbonza torture. Sword fu. Torch fu. Thigh fu (you have to see it to believe it)."

The fascinating thing about Roger Corman’s Concorde flicks is that they merge a feminist outlook with raw exploitation. Corman leading ladies are as tough as they are gorgeous. They have no patience for being pushed around, and they can out-think -- as well as out-fight -- pretty much everybody in the room. Still, they do have this penchant for taking their clothes off, making the males in the audience very happy indeed. Corman’s many disciples certainly borrowed the master’s strategy. When I saw that moment in Titanic when Kate Winslet poses for Leonardo DiCaprio wearing nothing but the Heart of the Ocean necklace, I knew that alumnus James Cameron had learned his Corman lessons well. Ditto for the smart, tough Sigourney Weaver strippng down to her scanties before rescuing her cat in Alien. (No, director Ridley Scott didn’t work for Roger, but Hollywood in the Eighties certainly picked up on Roger’s style, then added a much bigger budget.)

Movie heroines of old were always needing to be rescued. (See The Perils of Pauline, and everything starring Lillian Gish.) Corman heroines (like Angie Dickinson in Big Bad Mama and Pam Grier in just about everything) were always on the verge of being raped, tortured, or killed—but they knew how to turn the tables. That’s one of the very sad things about Lana Clarkson’s fate. In the movies, her Queen Amethea might have been threatened by rapacious bad guys, but she always managed to gain the upper hand. In real life, though, Phil Spector had her beat.

January 19, 2021

Sam Shepard: Writer, Actor, “The New Gary Cooper”

Shepard, as Yeager, is at left

Shepard, as Yeager, is at left

The story of Sam Shepard is one of Hollywood’s most unusual. How many of America’s award-winning playwrights also end up as full-fledged movie stars? As a serious theatregoer, I’d thrilled to the jazzy rhythms of Shepard’s 1972 play, The Tooth of the Crime. At L.A.’s Mark Taper Forum, I’d also been present in 1977 for a New Theatre for Now presentation of his Angel City, but joined two-thirds of the audience in not coming back after intermission. Still, I have serious respect for Shepard’s mature domestic dramas, which include the Pulitzer Prize-winning Buried Child (1979) along which such other mature works as True West and Fool for Love. No question that he’s one of the most essential American playwrights of his era.

So how did he wind up acting in movies? As John J. Winters’ definitive 2017 biography, Sam Shepard: A Life, makes clear, partly his native restlessness made him open to trying new things. And during his lifetime he always hung around with creative types who were ripe for experimentation. That’s how he chanced to be part of Bob Dylan entourage, charged with writing and shooting 1978’s ill-conceived Renaldo and Clara. In that same era, writer-director Terrence Malick convinced him to take the role of a taciturn farmer who’s blinded by his love of a much younger woman in the evocative Days of Heaven. The role suited him exactly: It turned out Shepard had no special gift for on-camera line-readings. But the camera loved his weathered features and the sense he projected of being close to the soil. The film’s producer explains how in the cutting room Malick “went with Sam’s silence and the way he looked when he had a big sky or a white field behind him.”

Five years later, he landed his best role: as flyboy Chuck Yeager in The Right Stuff. The film draws a contrast between Yeager’s authentic heroics and the flamboyant, petulant corps of Apollo astronauts. Fans remember the film’s opening, in which Yeager, on his horse, stares down a late-model jet amid the Joshua trees of the Mojave Desert. Director Philip Kaufman has said of this scene, “Sam’s got the persona of Gary Cooper, the tall solitary American on horseback.” The film earned him a 1983 Best Supporting Actor Oscar nomination, as well as a slew of offers for other acting roles. His second-billed 1982 appearance in a biopic called Frances had already introduced him to actress Jessica Lange, who would become the center of his romantic world for decades thereafter. Together they appeared in Country, in which he again explored his farming roots. And he played in other ambitious dramas too, such as Ridley Scott’s Somalia film, Black Hawk Down and the well-received (though annoyingly titled) The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, in which he took the role of Frank James in a starry cast that included Casey Affleck and Brad Pitt.

At the same time, Shepard was also fattening his bank account by accepting “paycheck” parts in trifles like Baby Boom and the mostly-female weepie, Steel Magnolias. After a while I stopped hearing about him, either as an actor or a playwright, and wondered why. Winters’ book has the answer, in an epilogue added to the paperback edition. On July 27, 2017, Shepard died of complications from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) at the age of 73. Stoic to the last, he had let few people know that a degenerative illness was stealing his life away, thereby robbing stage and screen audiences of a distinctive and memorable presence. Winters’ book fills in the gaps nicely.

January 15, 2021

Wonder Woman At Home On the Range: Joan Crawford’s Johnny Guitar

Why did I want to watch a pulpy 1954 western called Johnny Guitar? Let me count the ways. First of all, I’ve always been fascinated by the title. Secondly, it came out of an enterprising Poverty Row studio, Republic Pictures, that produced such major films as John Ford’s The Quiet Man and Orson Welles’ Macbeth, as well as hillbilly musicals, low-budget westerns, and flicks starring ice-skating queen Vera Hruba Ralston. Also, its director is Nicholas Ray, who began his career with haunting film noirdramas like They Live By Night (1949) and In a Lonely Place (1950), in which Humphrey Bogart gives one of his most distinctive performances. Just one year after Johnny Guitar, Ray charged into the bigtime by way of Rebel Without a Cause.

And then there’s the fact that the movie stars Joan Crawford. Yes, Mommie Dearest herself, an actress whose career began almost at the start of the movie era, in silent films. In the 1930s, she played flappers, but her great period began in 1939 with The Women, then continued into her Oscar-winning 1945 role as a self-sacrificing mother in Mildred Pierce. By the time she shot Johnny Guitar, she was about 50, on her third husband, and heading toward her Grand Guignol era, during which she subverted her glamour-girl image in grotesqueries like 1962’s What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?

Johnny Guitar, though, gives her a role in which she is strong and svelte. Though the title refers to a mysterious guitar-playing stranger (Sterling Hayden) who stumbles into a weather-wracked saloon in the middle of nowhere, Crawford’s Vienna is clearly the queen of this domain. From her first appearance, in sleek black slacks, at the top of a staircase, we know she’s in charge. She’s also generous to her friends, shrewd about her business dealings, and tough on the bad guys who exist in abundance in this out-of-the-way spot. And what about her heart? As the plot moves forward, she blossoms, even dressing at one point in a filmy white gown to signal that she’s emotionally engaged. But we should not be distracted by her revealing of her feminine side. True, at one point she desperately needs to be rescued, but fundamentally she’s a winner all the way. This gal’s tough, and she’ll prove it before the final fadeout.

By contrast, there’s a secondary female character, played by the always interesting Mercedes McCambridge, who denies her femininity in a way Vienna does not, and becomes, in the course of the film, her implacable enemy. Apparently the enmity was real: the two women hated each other, and it didn’t help that Crawford (who like McCambridge enjoyed abusing alcohol) was having an affair with director Ray during the shoot.

Instead of the usual good-guys-versus-bad-guys dynamic, Johnny Guitar benefits from a complicated triangular framework involving three factions. There’s Vienna and her employees at the saloon; her former lover and a batch of raggle-taggle misfits hanging out at a hidden silver mine; and finally the wealthy land baron (Ward Bond) and his minions who show up in both locales to foment trouble. Part of the fun is seeing such classic character actors as John Carradine, Royal Dano, and Ernest Borgnine show their stuff. Locations are cheap and unconvincing: there’s many a painted backdrop being passed off as the real thing. But the atmosphere within Vienna’s saloon is splendidly detailed and powerfully evocative. I suspect Quentin Tarantino had Johnny Guitar in mind when he created his own saloon as the chief set for The Hateful Eight. The world of Johnny Guitar, though, is less hateful than exciting.

January 12, 2021

Planes, Trains & Automobiles: Alfred Hitchcock Travels North by Northwest

When daily life seems bleak—surely the case in the past week or so—movies can waft us away to another place and time. I’m finding that watching a Hitchcock thriller helps to take the edge off more immediate worries. True, Hitchcock movies come in many shapes and sizes. Some are intimate; others were made on a grand scale. Some (like Psychoand The Birds) intend to scare the bejeezus out of us. Others wink at us that the dangers the characters face will eventually melt away.

When daily life seems bleak—surely the case in the past week or so—movies can waft us away to another place and time. I’m finding that watching a Hitchcock thriller helps to take the edge off more immediate worries. True, Hitchcock movies come in many shapes and sizes. Some are intimate; others were made on a grand scale. Some (like Psychoand The Birds) intend to scare the bejeezus out of us. Others wink at us that the dangers the characters face will eventually melt away. One of the very best in the latter category is 1959’s North by Northwest. This is a film that will give the viewer some queasy moments (notably in that scene in which Cary Grant is forced to drive drunk on a winding mountain road high above the Atlantic coast). But I suspect we’re more apt to feel gleeful as (in classic “wrong man” fashion) Grant’s stodgy businessman character is mistaken for a crafty spy, and then pursued all over the American continent by a group of thoroughly nasty types led by James Mason and a creepy Martin Landau. The very title “North by Northwest” wittily suggests deception. It’s borrowed from a moment in which Shakespeare’s Hamlet, feigning insanity in order to track his father’s killer, explains to the audience “I am but mad north-north-west.When the wind is southerly, I know a hawk from a handsaw.” (I can’t resist noting that this scheme doesn’t conclude terribly well for Hamlet, who winds up dead. Cary Grant is considerably more fortunate. In fact, I can’t think of any movie in which Grant is bumped off. No matter the pickle in which he finds himself, he always survives . . . and gets the girl.)

The script for North by Northwest was dreamed up by Hollywood veteran Ernest Lehman, who also contributed to the scripts of such classics as Sabrina, The King and I, and Sweet Smell of Success. He and Hitchcock agreed on a thriller that would hop, skip, and jump across the American landscape, ending up with a fight to the finish on Mt. Rushmore. In some ways, the film can be seen as an offbeat ode to American forms of transportation. After that near-deadly car ride, Grant’s Roger Thornhill (now suspected of a murder he did not commit) tries to escape his pursuers by hopping aboard the 20th Century Limited, choo-chooing its way to Chicago. In a cozy compartment he finds an attractive young lady (Eva Marie Saint), who may not be what she seems. But blissful train travel is followed by a scary scene in which—after being summoned to a mysterious cornfield—he finds himself chased by a low-flying crop-duster plane, in what is probably the film’s most famous scene. At the climax, though, everyone is on foot, scrambling past Lincoln’s granite nose on a convincing-looking (but actually studio-made) Mt. Rushmore.

It’s scary, yes, but it’s a lark all the same. An earlier film of Hitchcock’s—one he has called his very favorite—is much darker in all senses. While North by Northwest glows colorfully, 1943’s Shadow of a Doubt is a small black & white thriller that for a while seems as innocent as an early sitcom. A large, chaotic but happy family in comfy Santa Rosa, California is welcoming the mother’s beloved brother, Charlie, who’s just arrived from the east coast. Especially thrilled is the household’s eldest daughter, who was nicknamed after her uncle. Young Charlie (Teresa Wright) feels her dashing, courtly uncle (Joseph Cotten) can do no wrong. Alas, what she doesn’t know CAN hurt her.

Fans of my friend and former Corman colleague Steve Carver are now mourning his death. As a quick tribute, here’s a link to one of my several blog posts about this talented director and photographer.

January 8, 2021

Going Wild in the Streets: Then and Now

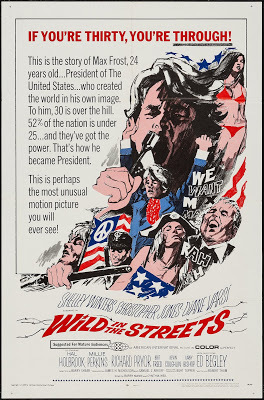

I was all set to write about film noir, or about George C. Wolfe’s masterful film production of August Wilson’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, with its remarkable valedictory performance by the late Chadwick Boseman. But the events on Wednesday in our nation’s capital led me in an even darker direction. With the wielding of political power very much on my mind, I remembered back to 1968, and the low-budget indie called Wild in the Streets.

Wild in the Streets began as a short story in the then-hip culture magazine, Esquire. “The Day it All Happened, Baby!”-- a darkly humorous account of the rising youth culture -- was authored by Robert Thom, who was then hired by American International Pictures to adapt his story into a low-budget screenplay with lots of music and youth appeal. The story’s hero, Max Frost (Christopher Jones) is a twenty-something who digs sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll. Fronting his home-grown band, he sings about the fact that 52% of the U.S. population is 25 or younger, This attracts the attention of a Kennedy-ish politician (Hal Holbrook) who reasons that a massive youth vote is just what his Senatorial campaign needs. He comes out in favor of changing the U.S. voting age from 21 to 18 (which, of course, actually was to happen in 1971), and commissions Max’s band to spread the word. Instead Max gains massive national attention with his audacious hit song about lowering the voting age even further: “Fourteen or Fight.”

I won’t get into all the complications that ensue, except to mention that large doses of LSD are involved, but ultimately Max becomes President, boosted into America’s top job because of his populist appeal to the youth of the nation. And his #1 priority? To take revenge on anyone older than 30. If you’re unlucky enough to be 35, you’re shipped out to a re-education camp, where (behind barbed wire) you’re drugged to ensure docility. That’s how he pays back his mom (the inevitable Shelley Winters) for being aggravating. But Max’s own days are numbered, as a nifty final scene makes quite clear.

Of course there’s no direct analogy to what’s just happened in the streets of Washington DC, and (needless to say) in the halls of Congress. And the presidency, of late, has seemed to go to septuagenarians, not post-pubescents. But the very idea of a charismatic leader and the enthusiasts who’ll follow him anywhere seems all too current. The insurrectionists who burst into the sedate chambers of the Capitol, bent on somehow ensuring their idol’s success, were promised a “wild” time in DC, and they got one.

I have a keen recollection of Robert Thom (who died at 1979 at the age of 50) from my New World Pictures days. He’d been hired to write the screenplay to the film that became Death Race 2000, and I actually chanced to meet with him over a working lunch. He looked very New York (sports jacket, cigarette, sardonic smirk), and seemed to look down his nose at us unsophisticated Californians. He ordered a Rob Roy (what was that?) and then steak tartare. Watching him gobble up raw beef seemed a perfect start to our work together on a script about auto racers who score points by mowing down pedestrians. But the few pages of script that emerged were hopeless: long literary arias that were all scene description. Robert Thom had a wild and crazy mind. He might have relished the anarchic spectacle we saw on Wednesday, but I suspect someone else might be better at making it into a timely action flick.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers