Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 46

May 28, 2021

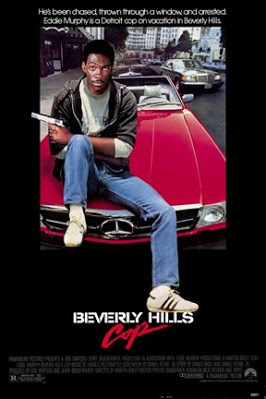

Defending (Not Defunding) the Police in “Beverly Hills Cop”

We’ve just passed the one-year anniversary of the death of George Floyd. Floyd’s murder under the knee of a Minneapolis cop has rightly led to impassioned public discourse about the role of policing in African-American communities. It’s no accident, at this particular moment in history, that so many of our major recent films – like Judas and the Black Messiah – have had something to say about the fraught connection between law enforcement and America’s Black citizenry. On television, such powerful shows as 2019’s When They See Us miniseries have zeroed in on the police role in demonizing innocent people of color.

But on the anniversary of Floyd’s death I yearned to watch something a bit lighter. Which is how I happened to queue up my TV to an oldie, 1984’s Beverly Hills Cop. The film has everything to do with the outrageous charms of Eddie Murphy, in the leading role of Axel Foley. But this was not a case (like Coming to America) of the film being a Murphy product from the start. It began as an action thriller that at one time was supposed to star Mickey Rourke. When Sylvester Stallone came aboard, the blood quotient was ramped up, and so was the budget. But then producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer made a major pivot to Eddie Murphy, who’d done well with comedies like 48 Hours and Trading Places. Suddenly the script’s renegade cop was not only a brilliant but independent-minded detective but also a major wise-ass, with a foul-mouthed quip for every occasion. The end result is an undercover police officer from a grungy Detroit precinct who shows up in Beverly Hills, supposedly on vacation but really to search (over the objections of his superiors) for the man behind the killing of a childhood buddy.

Beverly Hills plays itself, in all of its SoCal patrician glory. As someone who grew up in neighboring West L.A., just over the city line, I can attest to the authenticity of the Spanish-inflected civic buildings, the swanky boutiques, and the hordes of well-tanned sidewalk strollers, all of them dressed to impress. (It’s amusing, though, to see Foley enter the Beverly Wilshire Hotel—a distinguished hostelry in the heart of Beverly Hills—and then cross the lobby of Downtown L.A.’s equally historic Biltmore, where he cons a desk clerk into giving him a suite for the price of a single room.)

Critics as well as audiences loved Murphy’s live-wire performance. In Time magazine, critic Richard Schickel wrote that Murphy “exuded the kind of cheeky, cocky charm that has been missing from the screen since [Jimmy] Cagney was a pup, snarling his way out of the ghetto." Cagney, of course, scored big in the 1930s as an overgrown dead-end kid, one whose bravado exceeded even his talent for larceny. Murphy may be on the right side of the law, but he violates local rules and mores at every turn. In the oh-so-polite Beverly Hills police station, he pummels codes of conduct non-stop. As Schickel notes, he’s “ghetto” in his sassy rejection of the status quo . . . but there’s absolutely no overt racism to be seen in the way he’s approached either by fellow cops or civilians. Some of them may not like him much, but no one says (or even THINKS) the “N word.” And by the ending, of course, everyone but the bad guys is thoroughly on his side. Welcome to Neverneverland!

A word in passing on Eddy Donno, whose spectacular driving in the film won him a Stuntman Award. Well-deserved, and a big step up from his Roger Corman days.

May 25, 2021

On Olympian Heights: Remembering Olympia Dukakis

Through most of my moviegoing life, I’d never heard of Olympia Dukakis. But the New York stage veteran, born in 1931, made her first film in 1964. It was called Twice a Man, and she appeared in the credits as “Young mother.” It seems to have been her fate to play mother roles. In the course of a long career that ended with her recent death at age 89, she was credited as “John’s mother” in John and Mary, “Gig’s mother” in Made for Each Other, and “Joey’s mom” in The Wanderers. She also often showed up in authority roles, as judges, doctors, and a Mother Superior, as well as a high school principal in Mr. Holland’s Opus. But of course the role that made her, belatedly, a star was that of Cher’s feisty Italian mother in 1987’s Moonstruck. Rose Castorini is a nurturer, a pragmatist, and a philosopher, one who knows what it’s like to be hurt by love. She’s memorably relieved when daughter Loretta announces she’s about to marry a man she doesn’t love. Says Rose, glaring at her straying husband Cosmo: “When you love them they drive you crazy because they know they can.” Fortunately for Dukakis, she herself had a long-lasting marriage with a fellow actor, Louis Zorich, that produced three children and four grandchildren. So she came by her mom-credentials honestly indeed.

One of the things I most appreciate about Olympia Dukakis is that she always played intelligent women. Some of them might have done foolish things from time to time, but they were never dumb. Another thing I savor is the fact that she happily took on ethnic roles, giving them spirit and authenticity. As in Moonstruck, she made a great Italian mama, which was doubtless why she was cast as the unstoppable Dolly Sinatra in a 1992 miniseries about son Frank. And she was a convincing Jewish widow in The Cemetery Club. Curiously, despite her very Greek name and heritage, she rarely got the chance to portray her own ethnicity. She’s nowhere to be found in the cast list of My Big Fat Greek Wedding, the semi-autobiographical 2002 film by Nia Vardalos that found much of its initial popularity in Greek-American communities. She does, however, have the classical role of Jocasta in Woody Allen’s comic take on Greek mythology, Mighty Aphrodite.

In her later years, Dukakis took on challenging roles (like that of a trans landlady in the TV series Tales of the City and a so-called “butch lesbian” in Cloudburst). She was outspoken in promoting women’s rights and LGBTQ rights, and also stayed active as a well-loved drama teacher, both at NYU and in other theatre programs across the nation. A 2018 documentary film, called simply Olympia, chronicled her eventful life, including her growing-up years in a Massachusetts immigrant household, facing anti-Greek prejudice and a patriarchal family structure. Her parents certainly had a flair for names: her younger brother, Apollo Dukakis, is an actor I’ve enjoyed often on California stages.

Once I’d fallen in love with Dukakis in the delightful yet poignant Moonstruck, I was rooting for her to take home the Oscar for Best Supporting Actress. And she did. When the elegantly clad Dukakis mounted the stage, I was rather surprised that her speech was gracious but also somewhat sedate. I’d expected something more rambunctious from her, especially since it was well known that her cousin, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, was the Democratic candidate for President. But once she’d finished with her thank-yous, she confirmed my expectations by letting out a rip-roaring yell: “OK, Michael, let’s go!”

May 21, 2021

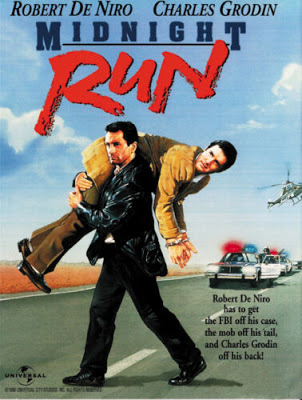

A Flight to the Finish: The Late Charles Grodin in Midnight Run

I come from a family of accountants. In my experience, CPAs tend to be hard-working straight shooters who put in long hours on the job and wouldn’t dream of getting wild and crazy. That’s one of the reasons I got a kick out of Midnight Run, the 1988 film that was a career highlight for the late Charles Grodin. This action dramedy, also starring Robert De Niro in one of his earliest comedic roles, tells an intricately plotted tale of an ex-cop-turned-bounty-hunter hired to apprehend an accountant who, has filched a mobster-client’s ill-gotten gains and donated them to charity. In order to get paid by a hot-tempered bail bondsman, De Niro’s Jack Walsh must transport nebbishy Jonathan Mardukas (Grodin) from New York to L.A. On the trail of the two men are some mobsters, a rival bounty-hunter, and the FBI, led by the towering, glowering Yaphet Kotto. All of whom want Mardukas for their own purposes.

De Niro, of course, is adept at playing a tough guy with a soft center. At first the movie is all his, as he exercises his considerable skills at lock-picking as well as tracking down missing accountants. Once he finds Mardukas in NYC and plunks him onto an L.A.-bound 747, we’re slightly disappointed that his quarry seems no more than a buttoned-down prig with a fear of flying. But in this film bland looks can be deceiving. As the two men travel together in trains, cars, and buses, we begin to suspect that Mardukas—so quick to trot out his financial opinions and persnickety health advice—is more complicated than he seems. That’s when Grodin’s apparently milquetoast character blossoms into someone with his own unexpected talent for larceny and much else. And it’s not giving much away to say that by the end of the film he and De Niro’s Jack have reached a meeting of the minds that is totally satisfactory.

Charles Grodin’s long screen career began in the late 1950s with a lot of episodic television. He was a finalist in the search for the right young actor to play Benjamin Braddock in The Graduate, and always clung to the story that he’d been offered the role but then, for some reason or other, turned it down. (When I was writing Seduced by Mrs. Robinson, the film’s producer, Larry Turman, insisted to me that – despite Grodin’s outstanding reading in a casting session – he was never chosen for the role.) Personally, I suspect Grodin would not have been the right choice to play Benjamin, who behaves very badly in the course of the film but still must have the audience in his corner. As Mike Nichols himself has noted, there’s a sweetness about Dustin Hoffman’s screen persona that makes people root for him, no matter what. Grodin, though, is more off-putting, even when he’s hilarious to watch. His own breakthrough role was in 1972’s The Heartbreak Kid, directed by Mike Nichols’ one-time artistic partner, Elaine May. Like Benjamin, the film’s Lenny Cantrow (Grodin) behaves outrageously once he’s fallen in love. But instead of succumbing to the charms of someone innocent and pristine like Elaine Robinson, Lenny falls hard for a beautiful, worldly-wise WASP (Cybill Shepherd) while he’s on his honeymoon with a nice young woman from his own community (played by May’s actual daughter, Jeannie Berlin). Yes, it’s funny, but he’s VERY hard to like.

Grodin’s whole career has been based on playing characters who are ambiguous in their appeal. One critic complimented the “inspired spinelessness” of his film roles, even in family movies like the Beethoven series. He’ll be sorely missed.

May 18, 2021

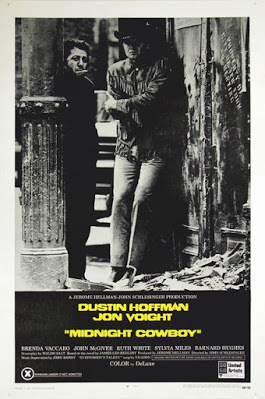

"Midnight Cowboy”: Some Sweetness Amid the Rot of the Big Apple

Once upon a time, Glenn Frankel was a foreign correspondent for the Washington Post, winning a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the Middle East. Then, seeking out a slightly quieter life, he began writing books about Hollywood classics. It’s easy to see that he was a fan of movie westerns in his youth. His first Hollywood book, The Searchers: The Making of a Hollywood Legend, explored in depth the John Ford drama that was perhaps John Wayne’s finest hour. He followed up with High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist and the Making of an American Classic. His latest take on celluloid cowboys is a wee bit different. This year he has brought forth Shooting Midnight Cowboy: Art,Sex, Loneliness, Liberation, and the Making of a Dark Classic. In this Oscar-winning 1969 drama, the “cowboy” is something of a phony, and he soon leaves his home on the range for a scruffy life on the mean streets of New York City. That’s where he plans to earn his keep as a male hustler, servicing sex-starved big city housewives. Except that things don’t exactly go as planned.

Frankel’s intensive research unearths the contradictions that went into the making of this landmark film. At its core – working against the sleaziness of urban life in the late Sixties – is the unlikely friendship of Joe Buck and Ratso Rizzo. Joe, played by apple-cheeked newcomer Jon Voigt, is naïve and unlucky, proud of his sexual prowess but repeatedly victimized by savvy New Yorkers of all persuasions. Ratso (Dustin Hoffman, coming off a very different role in The Graduate), is a down-and-out street bum from the Bronx. In a film wherein sex has nothing to do with love, the two discover a non-physical bond that is fragile but real. Emphatically, this is not intended as a film about a gay relationship. But the author of the novel on which the film is based, James Leo Herlihy, was a young closeted male. And its director, John Schlesinger, was a Londoner who played down his own homosexuality while beginning to make his mark as one of the rising British neo-realist directors of the era, along with Tony Richardson, Lindsay Anderson, and Karel Reisz.

Frankel devotes time and care to the place of this film within the annals of gay cinema. He decodes Joe Buck’s prized cowboy get-up, explaining why his John-Wayne-style hyper-masculinity proves so irresistible to the sad gay men he unwittingly attracts. He also delves into gay viewers’ response to Midnight Cowboy, comparing it tellingly to Schlesinger’s next film, Sunday, Bloody Sunday, which deals forthrightly with a bisexual man in the center of a love triangle that shows characters of both genders aching for love.

But Frankel is also terrific at dredging up production stories.. He explodes the legend that the car that almost hits Ratso on a busy New York street (leading to Hoffman’s “I’m walking here!” ad lib) was pure serendipity. And he explains the film’s famous X-rating as having been imposed not by a prudish MPAA ratings board but by the studio, United Artists, that made it. Who knew?

Midnight Cowboy -- convincingly acted, beautifully shot—is an easy film to admire. But perhaps it’s less easy to love. I’ve heard someone say, after watching, “It made me feel unclean.” A similar reaction came from Mike Nichols, shocked to learn his protégé Dustin Hoffman coveted the Ratso role. Nichols allegedly griped, “I made you a star, and you’re going to throw it all away? You’re a leading man and now you’re going to play this? The Graduate was so clean, and this is so dirty.”

May 14, 2021

Mike Nichols: Postcards from the Edge of a Career

It’s not easy for me to say nice things about film historian Mark Harris. Not that I’ve ever met Harris, and I doubt he knows I exist. But the publication of his first book, Pictures at a Revolution, ended up derailing my own book deal with a major university press, because I had planned to explore some of the same historic material his book had just finished covering. And when my Seduced by Mrs. Robinson: How The Graduate Became the Touchstone of a Generation appeared in late 2017, a reviewer in the New York Times posted a full-page review trashing my work, mainly because (as she herself pointed out) her good buddy Mark Harris had already written about The Graduate in a way she liked better. So it’s hard to be neutral about Harris’s achievements. even though I’ve heard from a professional colleague that he’s a good guy. Grrrr!

That being said, I read with great interest Harris’s brand-new biography of director Mike Nichols, who evolved from a comic sketch-artist (with partner Elaine May) into a major film director largely on the strength of early films like The Graduate. Surely this six-hundred-page tome was a book Harris was meant to write. Harris, you see, is married to playwright Tony Kushner. And Kushner’s Angels in America, a strikingly imaginative exploration of American history and the AIDS epidemic, became in Nichols’ skilled hands a landmark 2003 television production. So Harris, by way of Kushner and their circle of friends, knows pretty much everyone who was anyone in Mike Nichols’ long and complicated life.

As a film director, with a comedy career and a Broadway smash behind him, Nichols hit the ground running with an unexpected invitation to direct Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton in the screen version of Edward Albee’s corrosive Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? That work won him an Oscar nomination, and he went on to nab the golden statuette for his very second film, The Graduate. Then, just as he was beginning to seem invulnerable, he had a series of major artistic and financial flops that began with a misconceived version of Joseph Heller’s famous anti-war novel, Catch-22. Throughout a Hollywood career that ended with his death in 2014, Nichols moved in and out of favor, exploring a wide variety of genres and working with most of the industry’s brightest stars. For a while, in films like Carnal Knowledge (1971), he seemed to specialize in bitter humor from a male perspective. But lately I’ve been interested in a late-career series of movies (1983-1990) in which the female point of view emerges triumphant. This shift was apparently sparked by his teaming with Meryl Streep, the central figure in 1983’s political drama, Silkwood. In 1990, Streep took on the role of Suzanne in Postcards from the Edge, Carrie Fisher’s semi-autobiographical look at the life of an addict who’s also a Hollywood princess, thanks to the role of her superstar mother in her life.

Gossip columnists, of course, saw Shirley MacLaine’s character in the film as a riff on Fisher’s own mother, Debbie Reynolds, someone well past her prime but still itching for public adulation. (Throwing a surprise party after her daughter’s released from rehab, she belts out a sexy version of Sondheim’s a “I’m Still Here” for the guests). Nichols’ direction gives us the Hollywood environment in spades, filling small roles with classic showbiz personalities like Gary Morton, Rob Reiner, Gene Hackman, and even good old Mary Wickes. But the film is also honest about addiction, a subject Nichols himself clearly—as Harris shows us—understood all too well.

May 11, 2021

“Canned Laughter” in the Dark – Coming Soon to a Theatre Near You?

One of the pleasures of being Beverly in Movieland is encouraging the rise of talented young filmmakers. Chris Brake wrote to me from the south of England, just as he was launching a Kickstarter campaign to help fund his latest project. Chris, a London Film School graduate who makes short films with a fantasy twist, is working on Canned Laughter. It’s a distinctly idiosyncratic project about a retired comedian, Deirdre Gossamer, who misses the limelight. That’s why she knits herself an audience full of fans eager to enjoy her at-home performances. What she doesn’t anticipate, though, is a heckler in their midst.

As in an earlier effort called “Scraps,” Brake plans to mix live action with puppetry. Having grown up watching E.T. over and over, he’s a lifelong fan of puppets as a way to convey serious ideas. He still marvels at how E.T. “elicits sympathy from a lump of rubber and foam. Everyone always remembers it as a film about an alien, but it’s really not. It’s a story about divorce and the effect that has on a family. And that’s what puppetry can do; it can externalize something fairly abstract and introduce complex themes to an audience in a way that’s more palatable by being symbolic or allegorical.”

Though Chris has long been committed to filmmaking as a career, he took a major detour for a while into stand-up comedy. Fortunately, he managed to elude the hecklers who badgered some of his colleagues. His own brand of comedy relied heavily on rhythm, on “finding the perfect words when I write, so the thought of that flow being interrupted was terrifying to me.” He’s now able to see his retreat to film as “almost like seeking a kind of protection from potential criticism.” Film, of course, is a fixed medium: “You can engineer a scene to hit all of the emotional or funny beats you need it to, and it will play like that forever.”

Chris’s first-ever visit to a cinema was to see Disney’s Beauty and the Beast at the age of six. As he describes it now, “The whole experience has been permanently imprinted on me. I can recall almost everything about it; where we sat, the smell of the popcorn, the standees in the lobby, the dust in the projector-light, the line we had to wait in that snaked around the block, the woman behind us who made it about 10 minutes into the movie before realizing she was in the wrong screen and storming out shouting, ‘This ain’t the f***in’ Addams Family!’” To the young boy it mattered not at all that this cinema, the only one in his area, was “a total flea-pit.” Despite its sticky floors and stickier seats, he claimed it as a church of sorts, and later (once it gave way to the multiplexes) as “a treasure box of memories.”

Now the proud father of a teething 10-month-old, Chris looks forward to introducing his son to the joys of moviegoing. As of now the boy is much too young to see a whole movie, “but I’ve sat with him and watched some of the old Laurel and Hardy shorts that my own Dad used to watch with me as a kid. To me they’re really a perfect introduction to cinema because so much of it is silent, visual comedy that’s just beautifully silly. I think it’s a great gateway not only into cinema but also into its heritage.”

To help Chris and his work become part of that heritage, check out his Kickstarter page: https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/cannedlaughter/canned-laughter Or contact him directly at info@chris-brake.com

May 7, 2021

The Gates Split: Conscious Uncoupling at the Movies

The news of the marital rift of Bill and Melinda Gates has of course made headlines. It’s big news when one of the world’s richest—and most philanthropic—couples goes pffft! This is not just a case of a marital unit splitting apart: the conscious uncoupling (in Gwyneth Paltrow’s memorably weird phrase) of this particular husband and wife after 27 years of marriage may send shockwaves through our culture.

Oddly, their pending divorce makes me think back to classic movies from the 1940s. In an era when marriages tended to be forever, Hollywood released a whole slew of comedies in which the leading characters divorced, or threatened to. There was anger; there were tears. Nonetheless, hilarity ensued. Needless to say, before the lights came back up, the husband and wife whose holy union had been rent asunder (by jealousy, by miscommunication, by ambition or greed) were back in each other’s arms, newly committed to living happily ever after.

One of the earliest of these divorce comedies was The Philadelphia Story, the hilarious 1940 comeback vehicle for Katharine Hepburn, who had recently been named “box-office poison.” At the start of the film, she’s an heiress-type who’s very much divorced from the devil-may-care Cary Grant. And she’s on the brink of re-marriage to a bland chap with political ambitions when Grant’s character swoops back into her life. The presence of Jimmy Stewart complicates matters, and makes for a nifty subplot. But given the sparks that continue to fly between Hepburn and Grant, it’s easy to figure who will be reciting marriage vows at the film’s end. A similar story, though set in a newsroom, is another 1940s film starring Grant. This time, in His Girl Friday, he’s a newspaper editor, and his ex-wife is ace reporter Rosalind Russell. She’s engaged to the drab, domestically-inclined Ralph Bellamy, but her pending nuptials will deprive Grant of his best newshound. And darned if Grant and Russell don’t still love one another, despite it all. You can guess what happens.

Perhaps the strangest divorce comedy is Preston Sturges’ The Palm Beach Story (1942), in which wife Claudette Colbert loves hubby Joel McCrea so much that she decides to divorce him in order to further his career. He’s the designer of an experimental (read: really peculiar) airport that will save space by hovering above a city. Her plan is to marry a millionaire so as to be able to finance McCrea’s vision. In Florida she finds her loving millionaire (Rudy Vallee), but ultimately can’t bring herself to consummate the deal. The film is fascinating, though, because it’s about money as much as love.

Which brings me to a much more recent and much darker comedy, directed by Danny DeVito from a novel by Warren Adler. The War of the Roses (1989), starring Kathleen Turner and Michael Douglas, zeroes in on the split of an affluent couple, Barbara and Oliver Rose. They’ve had a long and apparently successful marriage, which includes the loving restoration of an historic mansion, but over time they’ve grown apart. When they decide to divorce, the ownership of the house and its contents is the big issue that keeps them at loggerheads. So viciously do they vie to hold onto what has been their shared property that the end result is not pretty. No happy reconciliation for these two, and no civilized parting of the ways.

It’s well known that Bill and Melinda have—in addition to an important charitable foundation—several fabulous luxury homes, notably a high-tech built-to-order mansion in Washington State and a Santa Diego beach house. Here’s hoping that, in the divvying up of their property, they don’t replicate the war of the Roses.

May 4, 2021

Monte Hellman’s "Cockfighter": Work from a Minimalist Master

It’s been a tough year for Roger Corman alumni, who’re dying off at a rate that gives me the shivers. The latest to fall, at the ripe old age of 91, is Monte Hellman, known for such minimalist fare as Two-Lane Blacktop, a road movie that sacrifices action and suspense to focus on the minutiae of life along America’s highways. That love-it-or-hate-it 1971 film, made after Easy Rider had taught Hollywood to view indie sensibilities with respect, was heralded by then-hip Esquire magazine as the movie of the year. Esquire’s April ’71 edition was devoted to the film, which featured the music world’s James Taylor and Dennis Wilson, along with Warren Oates and Laurie Bird, as competitors in a somewhat lackadaisical cross-country road race.

I had never heard of Two-Lane Blacktop when I went to work for Roger Corman in 1973. The day I first reported to the Sunset Strip offices of Corman’s New World Pictures, not sure how my ability to discuss Hemingway and Shakespeare would translate into work on nurse movies and biker flicks, I was handed a script for something called Cockfighter. It was written by Charles Willeford, a crusty Floridian adapting his own hard-boiled novel for the screen. Frankly, I found the story a bit strange: a tough-as-nails guy who scrapes together a living raising and betting on fighting cocks has made a vow not to speak until he’s awarded the Cockfighter of the Year medal he’s convinced he deserves. Having no idea how to critique a screenplay, I called on my literary instincts, and this seemed to do the trick.

While my colleague Frances Doel and I worked on our script notes, Monte Hellman came aboard as the film’s director. A longtime friend of Roger Corman, as well as a fellow Stanford graduate, he seemed to find the potential grittiness of the cockfighting world much to his liking. I have a vivid mental picture of Hellman in those days: a tall, thin man with an austere look and a corona of wispy black curls. He had already filled two roles with actors from the Two-Lane Blacktop quartet. Warren Oates, a longtime character actor who had also appeared in Hellman’s so-called “existential western,” The Shooting, would take on the non-speaking lead role. And Laurie Bird, who had played the aimless hitchhiker in Two-Lane Blacktop, was cast as a sexy young thing in the film’s early scenes. Now, making her second film ever, Bird was officially Hellman’s girlfriend, and I often saw her around the office. But hers was a troubled life, and I was sad to hear she’d committed suicide at age 26, in 1979.

I was not part of the film’s on-location shoot in rural Georgia. But I remember the excitement of the premiere in Atlanta: Roger thought local audiences would flock to a lurid film about a sport that was, in the words of our ad campaign, “dirty-violent and outside the law.” In fact, Atlantans seemed to regard the legacy of cockfighting with embarrassment, and we were soon trying out titles, like “Born to Kill,” that bypassed the film’s subject matter entirely. I quipped that we should consider “Naked Under Feathers,” but no one else seemed to find that funny. (Simultaneously we were working to convince the Humane Society that no animals had been harmed . . . yeah, right!)

I’m still not sure why Monte warmed to this unappealing material. But he filled the screen with great character actors, and obtained the services of the brilliant Spanish cinematographer Nestor Almendros, seven years before his Oscar-winning work on Days of Heaven.

Farewell, Monte! Thanks for the memories.

April 30, 2021

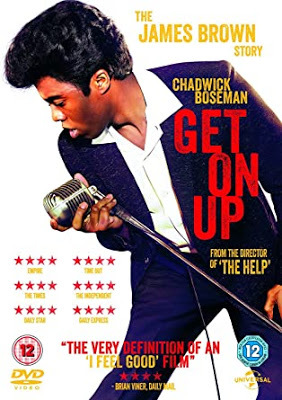

How to Turn Brilliant into Boring (even with Chadwick Boseman in the Lead Role)

The following was written before Oscar night. See below for my thoughts on why Boseman, despite all predictions, did not posthumously receive the Best Actor Oscar.

The following was written before Oscar night. See below for my thoughts on why Boseman, despite all predictions, did not posthumously receive the Best Actor Oscar. (1) Get the best talent money can buy. Get On Up not only has Boseman but also Viola Davis, in the small but key role of the mother who abandons young James but then, years later, sidles into his dressing room at Harlem’s Apollo Theater (Both Boseman and Davis came close to winning Oscars for their very different roles in Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.)

(2) Stage terrific musical numbers. Boseman only did some of his character’s singing, with Brown’s own voice also featured. But he dances up a storm, and has perfected Brown’s trademark leaping splits, while other musicians in the film are also first-class.

(3) Hire top-drawer craft personnel, especially those with expertise in hair and makeup. Brown’s black-black locks change their shape and trajectory in almost every scene. This helps the viewer keep track of the passage of time, which is extremely vital because the film’s chronology is so scrambled. (See #4.)

(4) Decide that cause-and-effect is not nearly so important as an arty bouncing between various widely separated eras. The viewer doesn’t dare blink, for fear of finding herself ricocheting from the piney Georgia woods of Brown’s early days to a crowded recording studio to a Paris concert hall to a country church. .

(5) Throw in some surreal touches for good measure. Why does young James encounter an unexplained lynched body in the woods? Yes, this might be true to the period, but how does it relate to this particular story? And why do we lurch from the funeral of James’ longtime manager (Dan Ackroyd) to a vision of Ackroyd lying dead on a golf course?

(6) Fail to decide what the story’s really about. This is a big one, as I emphasize to my screenwriting students. It’s not sufficient to take a subject from cradle to grave, cramming in every detail of a long, complicated life. The key is to focus on a particular area of concern, like Freddie Mercury’s homosexuality or Billie Holiday’s battle with the FBI. Get On Up wants to cover everythingabout Brown: his lost childhood, his introduction of a new musical style, his mixed feelings about women, his love/hate relationship with the country of his birth. This ambitious goal inevitably makes for a scattershot approach.

(7) Have plenty of loose threads: intriguing plot elements that surface, but then remain unexplored. Like that first wife: she’s lovingly introduced, along with their baby son, but then she disappears . . . and years later I gather it’s this particular son (Brown fathered at least 9 children) who’s fleetingly mentioned as having died off-camera in a car crash. It’s not good storytelling when you hear about an offscreen death and think, “Who?”

Follow these steps, and I guarantee that your audience will be on its way to slumberland.

* * * * * * * * *

And now some thoughts about what happened on Oscar night, when Boseman—to the surprise of all, including the evening’s organizers—lost the Oscar to 83-year-old Anthony Hopkins for his stunning work as a delusional old man in The Father.

(1) Academy voters assumed that Boseman (the sentimental favorite because of his early death) would surely win, which left them free to exercise their independence by exploring other options.

(2) Some voters strongly disliked Ma Rainey, considering this screen version of an August Wilson drama basically a filmed play, filled with performances more theatrical than cinematic. Their vote was a rejection of the lengthy theatre-style monologues that made Boseman’s work in the film so incendiary.

(3) Political correctness can be its own form of oppression. So much ink was spilled about the strong possibility of people of color taking all four acting prizes--to make up for past Academy wrongs -- that some voters doubtless deliberately chose to look beyond skin tones in making their choices. So the Oscar went to a Black man, a Korean woman, and two white actors. Diversity, right?

But what do I know?

(2

(

April 27, 2021

#OscarsSoMeh

Now that the 93td Annual Academy Awards Ceremony, honoring the best films of 2020, is in the books, it’s time to take a deep breath and think about what transpired Sunday evening at – of all places – L.A.’s venerable Union Station. Needless to say, the COVID pandemic had scrambled the usual plans for the festivities, along with rules requiring that all the nominated films debut in Southern California theatres before the close of the year in question.

Ever since the Oscar ceremony was first shown on television, it has always been a major way to entice worldwide audiences into theatre seats. Some of that strategy was certainly present at this year’s ceremony: producers cut away from the Downtown L.A. event to showcase clips from upcoming would-be blockbusters In the Heights and the Steven Spielberg remake of West Side Story. Both of these ambitious musicals feature singing and dancing on the streets of New York. For those of us who would LOVE to be dancing on New York streets rather than quarantined in our own homes, the clips were a tantalizing prospect of better things to come. Too bad they put to shame an Oscar ceremony with no singing, no dancing, and precious few clips of the nominees.

Given the challenge of staging a ceremony in the age of COVID, producer Steven Soderbergh opted for an intimate tone, with the few attendees present spaced out, supper-club style, at banks of small tables. (No food was consumed, though, nor was alcohol – the event hardly took on the boozy chumminess of the Golden Globes.) The time saved in not having big musical numbers and film montages was used to allow winners to speak at length, and to have hosts present cutesy facts about nominees’ first run-ins with Hollywood. (One had worked as a ticket-taker; another made popcorn in the lobby.) Sometimes this sense of intimacy worked nicely; elsewhere (as when participants traded in-jokes with their homies) we at home felt we were intruding on a private party.

Highlights? For me these included Best Supporting Actress winner Yuh-Jung Youn charmingly fawning over Brad Pitt as well as the truly inspiring tribute to Tyler Perry, who summed up the past year’s social discord with a ringing invitation to “Meet me in the middle . . . refuse hate!” I also got a giggle out of Glenn Close responding to a totally pointless song trivia game by revealing her deep knowledge of “Da Butt,” the hit dance tune written for Spike Lee’s 1988 School Daze, and then proceeding to shake her bootie in time to the music. (Was this bit planned in advance? It certainly might have been. If so, kudos to Close for being so good at projecting spontaneity.)

Low points? The attempts to build suspense by scrambling the order of presentations, with Best Director given early in the evening, and Best Picture upstaged by the Best Actress and Best Actor awards that followed it. Clearly the categories were re-arranged to allow for the posthumous coronation of the late, lamented Chadwick Boseman as Best Actor. Except (remarkably, given the strength of his performance and the sadness of his early death) he didn’t win. And winner Anthony Hopkins—superb in The Father, though his film did not seem quite as timely as some others—wasn’t present either physically or virtually.

Still the evening, such as it was, belonged to the austere and beautiful Nomadland. A salute to groundbreaking director/producer/writer/editor Chloë Zhao for her achievement and her pigtails. Amid a slew of beauties in slinky, boob-baring attire, her Princess Leia nightgown was elegant in its solemn simplicity.

Beverly in Movieland

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers