Beverly Gray's Blog: Beverly in Movieland, page 58

April 3, 2020

Roger Corman and the Pandemic Bandwagon

I don’t know what Roger Corman is doing right now, as he approaches his 94th birthday weekend. I hope he is self-isolating, along with the loyal Julie, in the Santa Monica home that was part of the nasty legal dispute with the two Corman sons. That dispute is apparently settled at last, as I’ve learned through a legal site specializing in showbiz matters. And I’d like to think that Roger—true to his nature—is busy planning out a quick and dirty flick that captures this peculiar moment in time.

We are, of course, in the midst of a pandemic, the likes of which the world has never seen. Roger has made at least two plague movies, versions of Edgar Allan Poe’s haunting (and prescient) “Masque of the Red Death.” Roger himself directed the Vincent Price version from 1964, which also starred the memorable Hazel Court as well as pretty Jane Asher, who was Paul McCartney’s main squeeze at the time. The film was shot in London, where the Brits know all about period filmmaking, and the cinematographer was a future directorial great, Nicolas Roeg. I had no part in that production, but was deeply involved with Larry Brand’s 1989 remake, which features a sad and eerie peasant striptease led by Corman favorite Maria Ford in a remarkable T&A moment that Poe doubtless never imagined.

Though the two “Masque” productions are rather effective, they were both made at times when a pandemic seemed, frankly, unthinkable. Still, Roger’s particular genius over the years has been to seize the moment, recognizing topics of high interest to the movie-going public and then hustling them out as quickly as possible. Such was the case with The War of the Satellites, a threadbare 1958 space epic launched immediately after the Soviet Union’s Sputnik had the whole world agog about space travel. Back in the 1950s, Roger was so artistically nimble—and so well established in the nation’s drive-ins and grind houses—that he could write, cast, film, and edit a quickie capturing the moment, then have it in theatres in a matter of weeks. By the late 1960s he was slightly more ambitious, taking it on himself to tackle the big events of the day (such as youth rebellion, biker gangs, psychedelics) in films like The Wild Angels, The Trip, and his AIP swan song, Gas-s-s-s! The last of these, ironically enough, posits a pandemic, one that kills everybody over the age of 25. Uh oh!

In my own era at Corman’s Concorde-New Horizons Pictures, movies took a bit longer to make and to distribute. And we were less concerned with dramatizing the events of the day than with jumping on the bandwagon of other filmmakers. I heard how, in response to the success of the first Star Wars, we ‘d built a studio and shot our own special-effects-heavy space drama, Battle Beyond the Stars. And Steven Spielberg’s Jaws led directly to our Piranha. I didn’t work on either of those (though I’ve spoken to many Corman alumni who did). But I was certainly around when dinosaur movies became a thing. While Spielberg was still shooting Jurassic Park, Roger set us to making our own flick about raptors running amok in the modern world. We bought a shoddy British novel and kept nothing but the title, Carnosaur. The goal was to beat Jurassic Park into theatres, which we did with weeks to spare. Between Siskel and Ebert, we got one thumb up. Today I’m giving a thumbs-up to Roger for his birthday celebration, and wondering what movie comes next out of his still-fertile brain.

Published on April 03, 2020 14:27

March 31, 2020

“Emma” and “Charade”: Close Encounters of the Romantic Kind

Now that I am housebound because of Covid-19 worries, I’ve been checking out a lot of feature films on my not-so-big TV screen. One I just watched was Emma, which Universal Studios was pragmatic enough – now that movie theatres are shuttered – to air on video very soon after its theatrical release. It’s not for me to comment on how the business model for Hollywood is being upended by the current pandemic. But I can record my feelings about this latest in a long line of Jane Austen adaptations for the screen. Emma, written by Austen in 1815, is a witty novel of manners about a very young woman who delights in her abilities as a matchmaker. Blessed with wealth, wit, and good looks, she takes charge of the social life of her small English village, with nearly disastrous consequences for all involved. But since Austen’s vision is a comic one, things right themselves in the end.

Emma has been filmed more than once. Gwyneth Paltrow played the title role in 1996, just after Amy Heckerling wrote and directed a delectable American adaptation called Clueless, set amongst the well-dressed teens at Beverly Hills High. The current version, starring Anya Taylor-Joy, has a welcome satiric edge, underscored by Autumn de Wilde’s witty directorial flourishes and by an offbeat score. I enjoyed it as a welcome diversion, but found little emotional reason to connect with this material. Maybe it’s a matter of timing. The characters in Emma, whatever their social station, all have their place in a tight-knit small community: there’s little chance for interaction with the outside world. But unlike those of us who are sheltering in place today, they don’t feel themselves the least bit isolated. Even ladies of leisure find so much to do. There are balls, picnics, small shopping expeditions; a young woman, like Emma, can also occupy herself with sketching, singing, playing the piano, and poking her nose into everyone else’s business. And, of course, just getting dressed and crimped and groomed (in the rather hideous sack-like fashions of the early nineteenth century) takes a fair amount of time. No sweatpants for even the stay-at-homes.

British character actors are always worth watching, and one of the treasures of this production is the great Bill Nighy as Emma’s discombobulated father. But one question I keep finding myself asking: why is it that today’s leading men (like Johnny Flynn’s Mr. Knightley) seem to underscore their masculinity through their failure to brush their hair? The heroes of old movies perhaps overdid the patent-leather-hair look, but I for one am tired of all those unkempt locks.

As a change of pace from Emma, I followed up with one of Hollywood’s great Golden Age treats: 1963”s Charade. This Stanley Donen classic stars an adorable Audrey Hepburn opposite an impeccable, every-hair-in-place Cary Grant. Instead of a quaint English village, we get Paris; instead of matchmaking we get murder, though the film’s violence is so deliciously low-key that there’s nary a fear of taking the story too solemnly. Hepburn’s heroine may be far more experienced than Emma—she’s a well-heeled married lady whose husband has just been offed under mysterious circumstances—but she is almost equally naïve in the ways of the world. And Grant’s character, with his shifting names and identities, represents a tough nut she has to crack. In one respect, Charade and Emma work in parallel: both feature a sweet young thing being wooed and won by a much older man. There was a 25-year-age difference between Audrey Hepburn (at 34) and Cary Grant (at 59), but no one has ever objected.

Published on March 31, 2020 11:20

March 27, 2020

“Outbreak”: Monkeying Around With a Pandemic

A pal who knows my movie-watching habit suggested I take a gander at Outbreak, on which her colleague had worked as a scientific advisor. Now that we’re all in a state of panic over COVID-19, this all-star 1995 thriller certainly seems timely. The question for me was this: would a movie about a raging viral epidemic freak me out?

Fortunately for the state of my nerves, Outbreak takes a very Hollywood approach to potential real-life disaster. Yes, it deals with a mysterious and terrible illness that begins overseas (in the jungles of Zaire) and then --through a series of mounting missteps -- begins spreading through the general population of a California town. The culprit is a particularly ugly, particularly nasty monkey who turns out to be the host of the mutating virus. It’s smuggled out of a science lab by a feckless employee (Patrick Dempsey) who tries to sell it to a pet shop. But then, of course, he ultimately Gets What He Deserves.

That’s Hollywood Rule #101: people get what they deserve. The Good Guys include a dedicated team of medical researchers, led by stalwart Dustin Hoffman (lightyears away from his iconic performances as underdogs Benjamin Braddock and Ratso Rizzo). He’s got an eager young sidekick, Cuba Gooding Jr., who freaks out at first but of course will eventually rise to the occasion. He’s got an acerbic scientist-buddy, played by a red-headed Kevin Spacey, who cracks jokes but is true-blue all the way. (I suspect this character is meant to be gay, which helps explain why he’s the one Good Guy who succumbs to the disease’s ravages, while everyone else mourns his loss.) Hoffman also has an estranged wife, Rene Russo, who is a fellow scientist. At the start of the film, their marriage is ending, strained beyond endurance by their competing careers, but you just know they still love one another.

In the Bad Guy camp, there’s creepy Donald Sutherland, a Major General who has his own nefarious uses for the deadly virus. Hollywood knows full well that a force of nature doesn’t make a good on-screen villain: you also need a human bad-guy on whom to fix all blame. And Sutherland, with his white mane of hair and his icy blue eyes, fills the bill perfectly. So fixated is he on keeping to his scheme that he’s ready to bomb the citizens of Cedar Creek back to the Stone Age. Lower down on the chain of command is a Brigadier General played by Morgan Freeman, who has a warm though feisty relationship with Hoffman’s Colonel Sam Daniels. When Hoffman pushes for a strong medical response to the budding crisis, Freeman stonewalls him. It’s not that he’s a genuine Bad Guy, but he’s under orders from Sutherland to keep the evil secrets under wraps. Still, he IS Morgan Freeman, so you know that at a critical moment he’ll Do the Right Thing.

And how, we wonder, does the epidemic end? Well, fortunately, it’s just a matter of tracking down that one host monkey and using its antibodies in a serum that instantly solves everyone’s problems (too late for poor Kevin Spacey, alas). Meanwhile, Major General Donald Sutherland is still out there with his bombs. And so a movie that purports to be about a medical crisis ends up with a big action sequence involving a whole lot of helicopters. That, of course, is Hollywood Rule#102: when in doubt, end with a chase scene

So this movie has it all: blood, guts, romance, diversity, helicopters. Spoiler alert: they all live happily ever after.

Published on March 27, 2020 11:27

March 24, 2020

Life as We DON’T Know It: “The Great British Baking Show”

I have been known to sit down with family members to play the board game rather modestly called The Game of LIFE. This particular amusement has been around for decades: the copyright on my version is 1985. Even ‘way back then, I knew that the game had little to do with life as I knew it. If you recall, you start out making the choice of attending college or going into business. If you go the college route, you are assigned a profession (law, medicine, journalism) and thereafter can count on a regular salary every time you pass Pay Day (It’s not a lot of money, but still!)

I should mention that your individual game piece is a small plastic car. You travel alone until, inevitably, you get married (which generates monetary gifts from the other players) and then add children, represented by small plastic pegs that are either pink or blue. Naturally you and your growing family face a few ups and downs, like business reversals and relatives moving in when least expected. But I certainly don’t recall anything drastic, like (let us say) war, tornado, earthquake, or global pandemic.

How do you win at LIFE? I just went back to the game to check. I had thought that all those tiny cars, with their teeny plastic passengers, might be heading toward something like Happy Acres (a rest home, or – shall we say? – final resting place). I looked hard, but couldn’t find this End of the Road destination on the gameboard. Instead, the rules on the box told me the following: “If there is no TYCOON, the game ends when the last player reaches BANKRUPT or MILLIONAIRE.” I should have known: in a game that sanctifies a capitalist outlook, the goal is to wipe out everyone else economically and stand alone, secure in your millions.

Particularly these days, that’s a message that has little appeal for me. Which is a long way of getting around to my favorite TV program to binge-watch. While sheltering in place, no longer allowed to drive my little car through the highways and byways of LIFE, I find myself really keen on seeing who can turn out a perfect kouign amann(for those not in the know, that’s a sweet and buttery Breton pastry) in three hours flat.

The Great British Baking Show serves a slice of life that is warm and comforting, if perhaps a trifle sugary. The contestants (carefully chosen to represent a wide swath of ages, races, and geographies) are given baking tasks that are increasingly challenging. As the clock ticks down, they follow cryptic recipes, make up their own inventive blends of flavors, and try to outdo one another with razzle-dazzle presentations. One thing that’s lovable is the show’s setting: the kitchens are set up in a big white tent, nestled on the verdant lawn of an English country manor. But it’s also heartening to see the genuine affection between the various contestants. The judges, the warm-hearted Mary Berry and the impishly acerbic Paul Hollywood (where do they get those names?) may be strict in their kitchen standards, but you sense that they’re fully on the side of these talented amateurs.

I’m not a baker: my biggest baking successes involve a boxed cake mix with a few added ingredients. So I’m not about to be inspired to try baklava with homemade filo dough, or that German cake made up of twenty thin layers, each grilled to the perfect shade of brown. But it’s refreshing at this troubled time to lose myself in uplift of the delicious kind.

This post is dedicated to Hilary Bienstock Grayver, whose sourdough loaves are to die(t) for.

Published on March 24, 2020 10:52

March 20, 2020

Thoughts on a Closed City

So have you watched Contagion yet? At this time of social panic, there’s much to be said for seeking out feel-good movies, in which we’re reassured that it’s a small (and healthy) world after all. But there’s another instinct at work, one that encourages us to locate the grim flicks that mirror our own current mood. Which means that films like Blade Runner, in which the social fabric has been rent asunder, seem all too appropriate.

European and Asian filmmakers have long been deft at showcasing a society gone mad. After reading about the horrors afoot in today’s Italy, my mind flashed back to a classic of Italian cinema, Roberto Rossellini’s Open City. This neo-realist masterwork, released in 1945, deals vividly with the life-and-death clash of Nazis and members of the Resistance on the streets of Occupied Rome. Today, however, Rome (like all Italian cities) is hardly open. Because of fears of COVID-19, total social isolation is now the law. Any film set in today’s Italy would be better titled Closed City.

As we Americans are increasingly living in Closed Cities of our own, I’m reminded of foreign-language films that run parallel to our current situation. These dark (though sometimes darkly comic) movies capture the paranoia that goes with our current need to shelter in place, sometimes alone, sometimes with others whose fear and anxiety can easily trigger our own. Days and weeks (and months?) cooped up with a spouse or partner can certainly help us identify with Jean-Paul Sartre’s famous stage play, No Exit (first produced in France in 1944 and filmed several times since). Its most celebrated line, “Hell is other people,” certainly sums up what we might begin to feel after a few weeks of conjugal isolation.

The motif of claustrophobia –a sense of the walls closing in--surely asserts itself in many art-house films. I can argue that it’s an element in Bertolucci’s notorious Last Tango in Paris. And it’s certainly present in a Japanese film from 1964, Teshigahara’s eerie, powerful Woman in the Dunes (based on Kobo Abe’s great novel), in which a man is trapped in a sand pit from which he can never escape. After a few weeks of what seems like house arrest, I suspect we’ll all start to know exactly how he feels.

Then there are the films that trade on our fears of the unknown, on a sense of lurking danger that’s coming to get us at any moment. There’s more than one paranoia classic I could cite, but a prime example is Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel. This surrealistic 1962 Spanish-language opus posits a group of well-heeled guests who find themselves terrified to leave the mansion in which they’ve all just dined. I understand their panic: I feel something of the same when I go out to move my garbage cans.

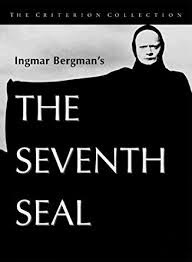

Perhaps the film that best addresses the current moment dates all the way back to 1957. I’m thinking of Ingmar Bergman’s Black Plague drama, The Seventh Seal, starring the late Max von Sydow as the medieval knight who plays a chess game to save his soul. I doubt that anyone is entirely clear on what Bergman was after, but his Dance of Death finale is hard to forget. It certainly wasn’t forgotten by my former boss, Roger Corman, who borrowed from Bergman’s visual imagery in adapting Edgar Allan Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death (1964). The Poe tale of a castle full of masked revelers who think that in their sanctum they have outwitted the plague seems all too relevant now. And, alas, all too plausible.

The Dance of Death from Bergman's "The Seventh Seal"

The Dance of Death from Bergman's "The Seventh Seal"

Published on March 20, 2020 10:34

March 17, 2020

As Germ-Ridden As It Gets : Jack Nicholson Finds Love

Now that we’re all compulsively washing our hands, Jack Nicholson’s behavior in the James L. Brooks romantic comedy As Good as it Gets, doesn’t seem all that strange.. Nicholson, playing Melvin Udall, is established as a man in the throes of obsessive compulsive disorder. Early in the film, we see him (just after he’s thrown a neighbor’s fluffy little dog down a trash chute) dive into his medicine cabinet, which is filled top to bottom with boxes of serious-looking hand soap. He tears open one box, lathers up, and thoroughly scrubs his digits. After which he tosses the barely used bar of soap into the trash.

Melvin has other tics too. He has a thing about the number five. He walks down Manhattan streets in strange patterns, apparently avoiding stepping on cracks. He eats daily at his favorite table at his favorite diner, where his favorite waitress (the acerbic Carol) tolerates his insistence on bringing his own disposal plastic utensils. So obsessed is he with germs that he’d rather go out and buy a sports jacket than borrow the one a snooty restaurant has on hand for underdressed patrons. These days I can’t blame him for worrying. Cooties? COVID-19?

If Milton’s germaphobia strikes home these days, so does the dilemma faced by Carol (played by Helen Hunt in an Oscar-winning performance). She has a young son with a serious asthma condition that leads to frequent ER visits, but her bare-bones HMO has made no real progress in addressing his medical issues. It’s not until the well-heeled Melvin steps in that she has access to a specialist who can take steps toward actually treating young Spence’s illness. It’s a clear case of income inequality, and I’m certain Bernie Sanders would have something to say about the fact that the hard-working Carol lacks the resources that Melvin can take for granted.

Melvin has made his money as the prolific author of romance novels. Which is not to imply that he has high regard for his readers. When an adoring secretary in his publisher’s office dares to ask how he creates the heroines she loves, he shoots her down with a blunt reply: “I think of a man, and I take away reason and accountability.” This is not a chap, obviously, who is good at relationships in the real world.

But at the heart of this film is an insistence that first impressions are not always accurate, and that there’s more to people than their outward appearance might suggest. Greg Kinnear plays (nicely) Melvin’s neighbor, Simon, who’s the owner of the little dog as well as a budding artist. Melvin has easily sussed out that Simon is gay, and he assaults his neighbor with slurs that would probably not be tolerated today in a movie rated PG-13. Eventually, though, the two become friends, and Simon helps pave the way for Melvin’s hard-earned happy ending. There’s also Cuba Gooding Jr., hilarious as always as an art dealer and a gentleman, but one who knows how to keep Melvin in line by insinuating his scary ghetto roots. Then there’s Carol, a blue-collar drudge who manages to be simultaneously smart, sardonic, wary of pain, and very very capable of love. And finally there’s Melvin himself, contemptuous of the sentimental fans of his writing, but underneath it all someone who’s fully ready to love and be loved. The film doesn’t laugh off his OCD issues, but when the chips are down this is a man who is able to say just the right thing: “You make me want to be a better man.”

Published on March 17, 2020 12:19

March 13, 2020

The Joker is Wild

Yes, it’s Friday the 13th, and I’m not exactly in the best of spirits. (So say we all, I’d imagine.) With COVID-19 seemingly lurking around every corner—and even Tom Hanks afflicted!—it’s hard to feel perky. Which explains, of course, why I chose this time to finally catch up on Joker. Frankly, the problems of his Gotham, exemplified by a garbage crisis and a lot of morose people in clown masks, didn’t seem so bad in the face of current reality.

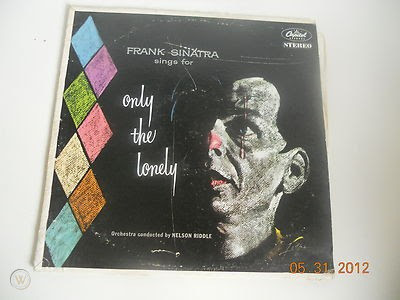

Not that I’ve ever had much affection for clowns. I’m one of those who consider them creepy rather than fun. The dual nature of clowns—the painted-on smiling lips hiding the woebegone interior—has not escaped a number of theatre artists. There is, of course, Leoncavallo’s famous 1893 opera, Pagliacci, in which an actor must “put on the costume” (“Vesti la giubba”) of a comic character despite his real-life wife’s infidelity. In the world of cinema, Fellini was fascinated by clowns, as was Charlie Chaplin, who mastered the art of conveying heartbreak through comedy. It was Chaplin who wrote the music for “Smile” (“Smile, though your heart is aching” ), a long-popular song based on his score for Modern Times. This song, in the classic Jimmy Durante version, is one of those oldies cannily featured on the Joker soundtrack.The Joker score won an Oscar for Hildur Guðnadóttir (no idea how you pronounce that), an Icelandic composer with a background in classical cello. Her ominous cello-heavy orchestral passages are certainly both appropriate and distinctive, and it’s marvelous to see—for the first time ever—a solo woman honored for her film music. But the tunes that stands out for me in Joker are the vintage pop ditties that serve as a counterpoint to Arthur Fleck’s morbid view of life. Along with “Smile” (and, apparently, a number of cues from Modern Times) these include Fred Astaire singing the lively “Slap That Bass” from Shall We Dance? as well as the cheerful kids’ perennial, “If You’re Happy and You Know It.” One of songs featured over the closing credits is the all too ironic “Send in the Clowns,” Frank Sinatra’s poignant version of the Stephen Sondheim classic. And popping up throughout the film is another song we generally associate with Sinatra, the wryly philosophical “That’s Life.” It’s fully apt that Sinatra be part of this film: his Only the Lonely album, one that scored a 1959 Grammy for its cover design, featured a black-and-white image of the man himself in Harlequin makeup.One reason for all the pop-culture nostalgia in this film seems to be that Arthur Fleck and his mother are suckers for the vibes of an earlier, and perhaps simpler, era. Their favorite home entertainment is a family-friendly TV talk show hosted by the avuncular Murray Franklin (played by Robert De Niro, of all people, as a cross between Johnny Carson and Oprah Winfrey.) It is Murray’s discovery of Arthur, and his airing of an embarrassing clip from Arthur’s attempt at a standup routine, that triggers the film’s climactic catastrophe. The fact that Arthur is so hungry for the sort of celebrity that a TV appearance can usher in says something about our societal determination to grab our fifteen minutes of fame. Not that Joker can be considered in any way a profound movie. Frankly, despite a gutsy and mesmerizing performance by Joaquin Phoenix, a lot of its ideas don’t particularly hang together. But in giving a backstory to Batman’s nemesis, filmmaker Todd Phillips smartly considers the way mass media (though, curiously, not comic books) shapes American lives.

Published on March 13, 2020 09:18

March 10, 2020

Little Globe of Horrors: The Corona Virus is Coming For YOU!

Fears of the Corona virus getting you down? If so, maybe you’d better stay away from the movies. One thing about this widespread popular art form: it often seems to mirror what’s on our collective minds. Horror and science-fiction films in particular often reflect an era’s nightmares: just look at all those nervous 1950s flicks in which a monster (like Godzilla, for instance) seems to stand in for a coming nuclear holocaust.

As a former Roger Corman person, I’ve been involved in more than a few of these cheap but potent disaster films. Mostly, of course, we at Corman’s Concorde-New Horizons were keen on grabbing a piece of the marketplace already occupied by big studio hits. When 20th Century Fox scored with the 1979 outer-space thriller Alien and its 1986 sequel, Aliens, we followed with an earthbound but not-all-that-different rip-off, 1989’s The Terror Within. While the big-budget Steven Spielberg dinosaur drama Jurassic Park was still in production in 1993, we were already forging ahead with our own low-rent dinosaur epic, Carnosaur. Our true goal, of course, was to capitalize on the enthusiasm generated by the big-money films. But whatever our underlying aim, we were also capturing onscreen that era’s biggest fear: the threat of environmental disaster.

Right now, of course, we’re all thinking about an advancing global medical crisis. At a time when we fear for the future, some “epidemic” movies from the past are starting to seem all too real to be viewed as simple entertainment. In 1971, while still a graduate student, I saw a preview screening of a medical thriller called The Andromeda Strain. In that genuinely scary flick, the medical crisis is jumpstarted by alien organisms brought back from a space mission: a reminder in an era when the Apollo program was still new that outer space exploration could pose its own risks to those of us remaining on earth. I haven’t seen more recent movies in this genre, those with titles like Outbreak (1995) and Contagion (2011), but they too posit the threat of a pandemic that the world is not prepared to conquer.

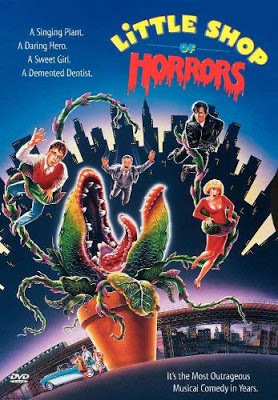

Surely the Roger Corman movie with the longest shelf-life, 1960’s The Little Shop of Horrors, deserves a mention here. This darkly comic tale of Audrey the man-eating plant was something of an impromptu effort, created by Roger along with favorite collaborator Chuck Griffith when some sets from another production proved available for three whole days. Who knew back then that among the teenagers falling in love with this fast-and-cheap flick would be budding musical theatre guys Alan Menken and Howard Ashman? In 1982, they launched an Off-Off-Broadway musical version of Little Shop that became a surprise hit. (Roger’s original film was never copyrighted, and his belated attempts to wring money from this stage smash are laid bare in my Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers).

When the Little Shop musical became a major Technicolor film in 1986, the disturbing stage ending in which Audrey II takes over the world was replaced by a far more upbeat finale. It’s only recently that I discovered film director Frank Oz’s much scarier original cut, which features man-gobbling plants running rampant in New York City (and presumably the rest of the globe). It’s an ending (see below!) that seems right in keeping with our current pandemic fears. Right now there’s a budding remake of this movie musical, with big names rumored for the major roles. I hope that by the time it blooms, this Corona outbreak will be a thing of the past. But we’ll probably have something else to worry about.

In case you’re curious about how the original Little Shop of Horrors was belatedly copyrighted, here’s a link to a 2013 Beverly in Movieland post that spotlights the heroics of Corman editor Steve Barnett, to whom we all owe a debt of gratitude.

Published on March 10, 2020 12:33

March 6, 2020

Fred Rogers and a Beautiful Day at the Kennedy Center

It’s taken me all this time to see A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, the 2019 feature in which one national treasure, Tom Hanks, takes on the persona of another, the late Fred Rogers. I admit I feel no special nostalgia for Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, the national program that kicked off on public television in 1968. My own kids were much more attuned to the lively, sometimes wacky humor of Sesame Street and its multiple inventive spin-offs (Square One,anyone? This memorable math show, which included a tongue-in-cheek Dragnetparody, was a big hit at our house).

I can see, however, how Fred Rogers (a man of many enthusiasms and enormous integrity) played an important role in the lives of many young children, especially those who were suffering from a lack of role-models. Rogers’ ability to communicate with people who are suffering – no matter what their age – is central to the plot of last year’s movie, in which a young writer (based on Esquire scribe Tom Junod) is helped by Mister Rogers to heal a rift that has torn his family apart.

What’s Fred Rogers really like when he’s away from his neighborhood? That’s part of the focus of Junod’s 1998 Esquire profile of Rogers. I haven’t read it, but I’ve been lucky enough to get a glimpse of the off-camera Rogers through a memory-piece by the always interesting Dale Bell. Bell, a friend who once helped produce the movie Woodstock, was also executive producer of Kennedy Center Tonight, the ground-breaking performing arts series that ran on PBS from 1980 to 1985. The program, which evolved from Bell’s deep admiration for the late President Kennedy, was intended to humanize the great performers who appeared on the Kennedy Center stages.

As the first entry in the Kennedy Center Tonight series was about to go before the cameras, Dale ran into Fred Rogers, whom he had known from Pittsburgh’s WQED. When Fred learned that the inaugural show would be a celebration of composer Aaron Copland’s 80th birthday, featuring such stellar musical talents as Leonard Bernstein and cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, he couldn’t contain his enthusiasm. A trained musician himself, he quickly agreed to be among those making the trek to Washington DC for the taping.

On the drive down, Rogers admitted why he had first aspired to be a musician: “I was very lonely growing up. I didn’t have many friends. I had to make up my own worlds. There, I could listen to my characters, or my puppets, and help them to deal with their problems, which were my own. My love of music was my constant inspiration.”

When Dale asked Bernstein, Copland, and Rostropovich if they were willing to have a special guest backstage, they (in Dale’s words) “erupted in joy that they were going to meet the creator and star of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. There were mammoth hugs all around.” As Dale remembers it, “This entourage, linked by hands that loved making music, this whole chain of sudden new-found friends and colleagues and comrades, was led out on stage among all of the players, who began tapping their music stands with their bows, and blowing their horns. Fred Rogers, adored by millions of children, was alive and arriving on the Concert Hall stage at the Kennedy Center.”

And that’s how Mister Rogers—in his trademark cardigan and sneakers—came to sit down at the Kennedy Center grand piano to pound out “Happy Birthday to You” in Copland’s honor. Clearly, it was a beautiful day in D.C., a place that could certainly use some beautifying, and Fred Rogers’ gentle touch.

Published on March 06, 2020 09:02

March 3, 2020

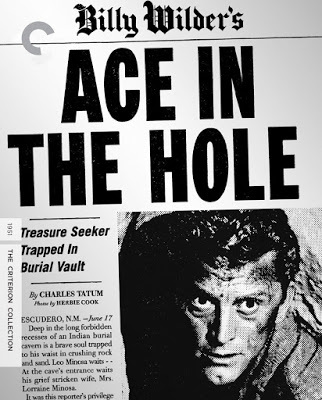

Ace in the Hole: Kirk Douglas and Billy Wilder’s Winning Hand

Movies don’t come much more timely than Billy Wilder’s 1951 drama, Ace in the Hole. It was shot two years after Wilder directed perhaps his most influential drama, Sunset Blvd., and just before he embarked on a long string of exuberant comedies, including Some Like It Hot and The Apartment. Ace in the Holealso marked the single teaming of Wilder with actor Kirk Douglas, who had just zoomed to stardom in Champion. In that tough-minded boxing film, Douglas had scored as a cynical pugilist. Ace in the Hole moves him into the world of daily journalism, putting a provocative spin on the idea of “fake news.”

The Austrian-born Wilder, who started his career as a Berlin journalist before the rise of the Nazis, obviously knew and cared about the power of the press. Press freedom of course is a cherished American ideal, but one that is easily exploited by men (and women) who are ruthless and opportunistic. Such a one is Douglas’s Chuck Tatum, a newspaperman who finds himself stuck in small-town Albuquerque, but will do anything to get back to the bright lights of New York City. All he needs, it seems, is the right human-interest story, one that will feed the public’s imagination day after day and allow him to place himself at the center of the action.

Such a story pops up in a rural backwater, where a local has entered a crumbling Indian cliff dwelling and found himself trapped. Tatum immediately begins calling the shots, personally communicating with the trapped man and his family, using all his wiles to endorse a rescue plan that encourages the maximum amount of public attention. (The film references a famous 1925 real-life incident in which Kentucky cave explorer Floyd Collins became similarly trapped for some two weeks. The local newsman who brought his day-to-day story to the world won a Pulitzer Prize, and the whole tragic episode proved the power of broadcast news to galvanize the entire nation.)

Ace in the Hole seems to me a rather perfect title, reflecting as it does both the idea of a man entrapped and a gambler’s reliance on a stroke of luck on which to base his cold calculations for success. But Paramount Pictures also toyed with titles like The Big Carnival, reflecting the party atmosphere that springs up around the site where Leo Minosa lies buried, complete with carnival rides, food booths, and folksingers wailing out ditties in the felled man’s honor. The national press, of course, descends too, as had happened for real in 1949 when little Kathy Fiscus fell into a California well. If it’s a media circus, Tatum serves as the ringmaster, cajoling Leo’s restless wife (Jan Sterling) into looking appropriately grief-stricken, and craftily furthering his own career.

This being 1951, he gets his comeuppance at last, but guilt hits him all too late. The bitter taste of his last line to the assembled crowds – “The circus is over” – probably rankled midcentury audiences, living in an optimistic post-World War II era. So Douglas’s indelible performance was mostly ignored. The film was not a hit in the U.S., and got little in the way of awards attention, despite a strong showing overseas. Today no less than Spike Lee considers it one of Hollywood’s very best films, one that boldly predicted the power of mass media as we know it.. He also sees it (along with the equally cynical A Face in the Crowd) as one of the film industry’s strongest statements about American greed: “If there’s a buck to be made, it’s gonna be made.”

Published on March 03, 2020 13:13

Beverly in Movieland

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like t

I write twice weekly, covering topics relating to movies, moviemaking, and growing up Hollywood-adjacent. I believe that movies can change lives, and I'm always happy to hear from readers who'd like to discuss that point.

...more

- Beverly Gray's profile

- 10 followers